1. Introduction

Rice serves as the primary food source for over half of the world’s population [

1,

2], serving as a vital food crop for achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 2030 of Zero Hunger [

3]. China ranks second globally in the rice cultivation area, with a perennial planting area of 30 million hectares [

4]. In mechanized rice cultivation, the paddy field bottom layer serves as a critical component within the tillage soil structure, bearing the operational loads of agricultural machinery. During operation, machinery encounters vibrations, bouncing, and bogging due to uneven pits and ruts in the bottom layer, significantly impacting both the passage of machinery and the quality of field operations [

5]. As agricultural production rapidly advances toward intelligent and labor-saving practices, the autonomous navigation and precise control capabilities of paddy field machinery have become critical for realizing smart farms with reduced labor requirements in rice production [

6]. However, the complex and variable contour of paddy field hard bottom layer surfaces [

7] remains poorly understood in terms of its impact on the position and attitude changes in agricultural machinery. This lack of clarity constrains the optimization of operation control strategies and hinders the advancement of intelligent operation levels, so it is imperative to elucidate the influence patterns of typical hard bottom layer contours on the position and attitude changes in agricultural machinery. Early terrain mechanics theories provided the foundation for modeling wheel–ground interactions. Bekker and Wong systematically established mathematical models for soft soil bearing capacity, settlement, and rolling resistance, offering theoretical support for vehicle dynamics response research [

8,

9]. Jia et al. proposed a wheel–terrain interaction model based on wheel dynamics and terrain mechanics, effectively simulating wheeled movement in soft soil and enabling numerical simulations for off-road mobile robots [

10]. Misaghi et al. employed the International Roughness Index (IRI) to model road surface irregularities in truck–road interactions, quantifying the effects of truck suspension systems and road conditions on pavement damage [

11]. Zheng et al. [

12] identified the driving environment as the most significant external factor influencing vehicle dynamics. They investigated the effects of varying road roughness, adhesion coefficients, and road gradients on the dynamic performance of dual-clutch transmission vehicles. Inotsume and Kubota [

13] proposed an adaptive terrain passability prediction method based on multi-source transfer Gaussian process regression. This approach utilizes limited data from low-risk terrain within the target environment, combined with prior travel experience across diverse terrain surfaces. Golanbari [

14] identified soil deformation as a key factor affecting off-road vehicle performance. They investigated soil deformation caused by the interaction between pneumatic tires and track wheels with the ground. The fitted surfaces obtained using optimization algorithms effectively predicted soil deformation induced by different wheel types.

In studies examining the impact of complex farmland topography on agricultural machinery operations, Tu et al. [

15] proposed methods for quantifying paddy field hard bottom layer contours, tillage layer thickness, and their characteristics based on machinery pose information. They developed a method for quantifying hard bottom layer contour features, providing a driving environment map for agricultural machinery. The primary factor affecting autonomous agricultural machinery path-tracking accuracy is lateral deviation caused by skidding under terrain influence [

16]. To address terrain-induced lateral deviation in agricultural machinery, Bevly, Ryu, and Anderson et al. [

17,

18,

19] employed a dual-antenna Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) system and Inertial Navigation System (INS) sensors to establish a kinematic model-based heading Kalman filter. This approach enabled the estimation of center-of-mass lateral deviation angles and front-rear wheel lateral deviation angles, further facilitating the estimation of wheel lateral deviation stiffness. To suppress disturbances from wheel lateral deviation, researchers treated lateral deviation as a disturbance term in linear motion models and employed robust control techniques for mitigation [

20]. Alternatively, they developed vehicle dynamics and kinematic models incorporating lateral deviation parameters, applying nonlinear control techniques to design path-tracking control laws [

21,

22]. Lenain et al. [

23] developed front and rear wheel yaw angle observers based on extended kinematic equations for front-wheel steering and four-wheel steering agricultural vehicles, utilizing dual-antenna GNSS and INS. They applied the estimated values to path-tracking control, effectively enhancing tracking accuracy. Regarding operational effectiveness, Zhou et al. [

24] addressed the tilting and height fluctuations in leveling machines caused by uneven hardpan layers in rice fields. They designed a leveling machine based on dual-antenna GNSS positioning and orientation, achieving horizontal and elevation control of the leveling blade after terrain-induced attitude changes. Frey et al. [

25] proposed integrating LiDAR and visual data with the RoadRunner framework, employing end-to-end learning to predict off-road terrain passability and elevation maps. Sten et al. [

26] combined the precision of LiDAR with the coverage complementarity of stereo vision to construct more comprehensive terrain surface models, providing more reliable inputs for vehicle-trapping assessment and path planning.

The above research demonstrates that terrain undulations significantly impact vehicle driving stability and agricultural machinery operation quality. Relevant studies have laid a solid foundation for analyzing the operational characteristics of agricultural machinery in complex terrain conditions, covering aspects such as terrain mechanics modeling, vehicle dynamics response, path-tracking control, and terrain perception. These studies enable real-time acquisition of agricultural machinery attitude information, construction of paddy field operation environment maps, extraction of hard bottom contour features, and quantitative description of unevenness. They have also partially revealed the patterns of terrain undulation affecting the operational stability and work precision of agricultural machinery. Multi-source information fusion methods incorporating LiDAR, stereo vision, and radar can assess vehicle passability on hard surfaces. However, research remains limited on the coupling relationship between local contour features of paddy field hardpan beneath water and tillage layers and the motion state of agricultural machinery, the response patterns of key attitude parameters, and the mechanisms of vehicle trapping. Particularly in typical ridge-and-furrow and vehicle-trapping scenarios, systematic experimental analysis and theoretical support are lacking regarding how characteristic parameters of the hard bottom layer—such as height, height differences, and local roughness—influence machinery trajectory deviation, attitude response, and escape capability.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper focuses on paddy field machinery and designs an integrated platform for acquiring agricultural machinery position/orientation information and hard bottom contour data based on GNSS and AHRS sensor fusion technology. It proposes a method for simultaneously obtaining the motion state of agricultural machinery during operation and hard bottom contour information, constructs motion state datasets for key points such as the antenna, bottom of the wheel, and rear axle center, and establishes a correlation analysis method between motion state and hard bottom feature parameters. Building upon this foundation, the study analyzes the mechanism by which typical hard bottom layer contours influence agricultural machinery movement trajectory deviation, attitude response, and bogging behavior. It reveals the patterns of how hard bottom layer contour characteristics affect the operational stability and precision of agricultural machinery. This study aims to provide theoretical foundations and technical support for optimizing the structural design of paddy field machinery, improving path-tracking control algorithms, and developing vehicle-trapping early warning strategies. It holds significant importance for enhancing the intelligence and operational efficiency of wheeled agricultural robots, as well as advancing smart production in paddy fields and unstructured complex terrain scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Platform for Collecting Position and Attitude Information of Agricultural Machinery and Hard Bottom Contour Data

Using a wheeled agricultural machine equipped with an autonomous driving system as the mobile platform, a GNSS (UB48; horizontal accuracy: 0.8 cm + 1 ppm; vertical accuracy: 1.5 cm + 1 ppm; heading accuracy: 0.2° with a 1 m baseline, Beijing Beidou Navigation Engineering Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and an AHRS (HWT605; static roll/pitch bias: 0.2–0.4°, Wit Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) are installed on the machine’s chassis. The GNSS measures the real-time spatial position and heading information of the machine during operation, while the AHRS measures the motion attitude of the chassis. A time-stamp synchronization method is employed to synchronously collect the machine’s position and attitude data. During field operations, the wheels contact the hard bottom layer of the paddy field. Continuous contact points between the bottom of wheels and the hard bottom layer form a point cloud representing the hard bottom contour. Based on measured position and attitude information—including the machinery’s spatial position, heading angle, and chassis pitch angle—the Euler transformation method establishes the bottom of the wheel motion trajectory model in the global coordinate system [

8]. GNSS spatial positioning and orientation data, combined with AHRS roll and pitch attitude information, are processed through sensor calibration and outlier handling to reconstruct the hard bottom contour terrain traced by the machine’s wheels. A visualizable hard bottom contour digital model is then constructed using a triangulated mesh method based on the collected point cloud. The designed agricultural machinery pose information and hard bottom contour perception platform are shown in

Figure 1a, while the data acquisition process is illustrated in

Figure 1b.

2.2. Correlation Analysis Method Between Agricultural Machinery Operational Motion States and Contour Feature Parameters

2.2.1. Method for Extracting Agricultural Machinery Operational Motion State Parameters

The onboard GNSS dual-antenna satellite positioning system enables the main antenna to capture the spatial position of the agricultural machinery antenna installation point within a local tangent plane coordinate system, along with the working speed and heading angle between the two antennas. The integrated AHRS system measures the pitch and roll angles of the agricultural machinery chassis. During actual operations, the agricultural machinery undergoes frequent attitude changes. The position of the main antenna cannot fully represent the machinery’s motion state when it is not level. Therefore, the motion states of the bottom surfaces of the left and right rear wheels and the center of the rear suspension are used to express the machinery’s true motion. By establishing a vehicle coordinate system, coordinate increments relative to the main antenna installation position are obtained for the bottom of the left and right rear wheels. Real-time motion information for the rear wheel bottoms is derived through continuous conversion based on the main antenna position and the vehicle’s current attitude. The relationship between the local tangent plane coordinate system {t}, the vehicle coordinate system {b}, and the position of the rear wheel bottoms is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Due to the rotational relationship between the bottom of wheel and wheel hub, the effect of rotation on the bottom-of-wheel position must be considered. This involves analyzing the change in coordinate increments of the bottom of the wheel within the vehicle body coordinate system during body pitch. The positional relationship during body pitch is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Let the right wheel’s base point be

, with coordinates

in the vehicle body coordinate system. It is expressed as a matrix as follows:

Among these, denotes the distance between the two positioning antennas, represents the distance between the left and right wheel hubs, is the vertical distance from the antenna positioning center point to the right rear wheel hub D, and is the distance projected along the X-axis of the vehicle coordinate system from the antenna positioning center point to the right rear wheel hub D. , , and represent the incremental coordinates of the bottom of the wheel relative to the wheel hub in the x, y, and z directions of the vehicle coordinate system, respectively. denotes the rotation angle of the vehicle coordinate system relative to the local tangent plane coordinate system’s X-axis, and is the wheel diameter.

Let the transformation matrix for converting point set coordinates in the vehicle body coordinate system to the local tangent plane coordinate system be

. The rotation matrix about the

Z-axis is

, the rotation matrix about the

Y-axis is

, and the rotation matrix about the

X-axis is

. This leads to the following:

Taking the bottom of right wheel as the sampling point, let the position coordinates of the main antenna in the global coordinate system {e} be

eP

A (B, L, H). After Gauss projection transformation to the local tangent plane coordinate system {t}, the coordinates become

tP

A (x

At, y

At, z

At). Let the set of

tP

A coordinate points for point A of the main antenna in the local tangent plane coordinate system be

and the coordinate set of the bottom of the right wheel point in the local tangent plane coordinate system after Euler transformation be

. This leads to the following:

Similarly to setting the left wheel center point as

, the coordinates of

in the vehicle coordinate system are expressed as a matrix:

The set of points

obtained by Euler transformation of the base point coordinates of a revolver in the local tangent plane coordinate system satisfies the following equation:

Let the center point of the rear axle be as

. The coordinates of

in the vehicle body coordinate system are expressed as a matrix:

Let the center point of the rear axle be

. The coordinates of

in the vehicle coordinate system are expressed as a matrix:

The ePA point cloud undergoes Gaussian projection and Euler transformation to obtain the coordinate matrices , , and for the right rear wheel bottom layer, left rear wheel bottom layer, and rear axle center in the local tangent plane coordinate system. Based on these coordinate positions, the displacement, velocity, and acceleration of the agricultural machinery’s wheel bottoms and rear axle center are derived. These provide the motion-related input variables for analyzing how hard-surface contour excitation influences the agricultural machinery’s pose.

By applying differential operations to the positional time series data from the bottom of the left and right wheels and the center of the agricultural machinery’s rear axle, the corresponding kinematic parameters of the machinery can be derived. Specifically, performing first-order differentiation on the displacement time series of the left and right wheel bottoms yields the linear velocity of the right wheel bottom, the linear velocity of the left wheel bottom, and the velocity of the agricultural machinery’s rear axle center, respectively.

Taking the calculation of the right wheel’s baseline motion parameters as an example, let the right wheel’s baseline velocity be

and its baseline acceleration be

. Using a discrete difference form, the calculation yields the following:

where

n denotes the time step index, and Δ

t represents the sampling interval. For the 10 Hz frequency data acquisition in this paper, this value is 0.1 s.

Similarly, the left wheel base velocity

, left wheel base acceleration

, vehicle center velocity

, and vehicle center acceleration

can be calculated. Furthermore, to reflect the instantaneous directional change state during agricultural machinery movement, introduce the left–right wheel base velocity difference

and acceleration difference

, which yields the following equations:

Based on data acquired from satellite positioning and attitude sensors, a complete mathematical mapping relationship is established through differential operations. This relationship transforms observational data from various parts of the agricultural machinery into parameters describing the motion state of the bottom of the wheels and the center of the rear axle. This provides input for analyzing the relationship between the motion state of the agricultural machinery and the contour characteristics of the hard bottom layer.

2.2.2. Method for Extracting Contour Feature Parameters of the Hard Bottom Layer

Agricultural machinery operates on hard bottom layers, with wheels exerting force upon the hard bottom layer contour. Due to the absence of shock-absorbing suspension on the rear axle, the contour surface of the hard bottom layer directly impacts the vehicle’s wheels. This force induces displacement and attitude changes in the wheels contacting the hard bottom layer. By utilizing GNSS position and AHRS attitude data from the machinery, discrete point clouds

(Equation (6)) and

(Equation (8)) representing the bottom of left and right wheels are reconstructed. Through automatic sensor calibration, outlier removal, and 3D spline curve denoising of the contour trajectory, a digital model of the hard bottom layer contour traversed by the machinery is constructed [

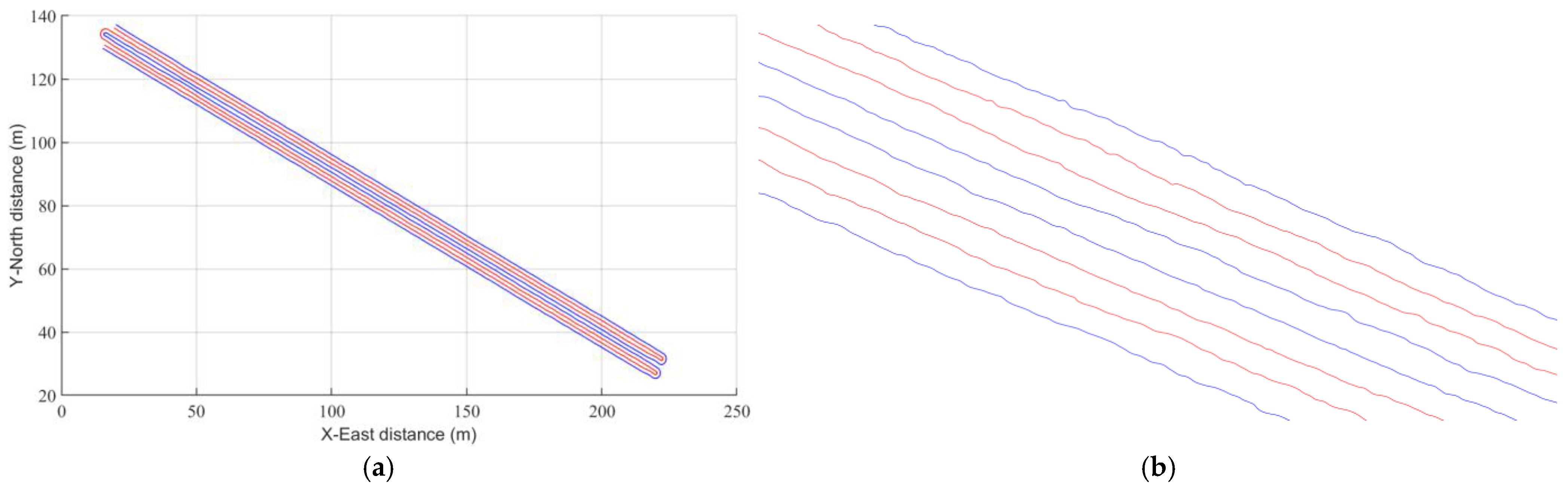

8]. In practical field operations, agricultural machinery primarily follows planned straight sections. The quality of straight-line segment operations critically impacts overall field performance. To extract representative hard bottom layer trajectory patterns, straight-line segments were isolated from the full-field hard bottom layer contour. The full-field wheel bottom trajectory is illustrated in

Figure 4. The actual hard bottom layer contours of the left and right wheels of the agricultural machinery were isolated. Continuous scattered points were then fitted with spline curves to form smooth hard bottom layer contours, as shown in

Figure 5.

Based on the coordinate points connecting the 3D spline curve of the hard bottom layer contour, isolate the contour points of the hard bottom layer in contact with the bottom of left wheel. In the local tangent plane coordinate system, the X-axis coordinate value is , the Y-axis coordinate value is , and the Z-axis coordinate value is . Additionally, the X-axis coordinate value , the Y-axis coordinate value , and the Z-axis coordinate value of the hard bottom layer contour points contact the bottom of right wheel in the local tangent plane coordinate system, while the Z-axis coordinate height difference between the hard bottom layer contours contacts the bottom of the left and right wheels.

To further analyze the impact of localized characteristics of the hard bottom layer on the movement state of agricultural machinery, the surface roughness of the hard bottom layer is introduced to represent the degree of localized undulation. Based on the contour information of the hard bottom layer, a section spanning the agricultural machinery’s wheel base length was selected locally. A straight line was fitted using the least squares method, and the height of each point relative to this fitted line was calculated. The relationship between the hard bottom layer contour, the locally fitted line segments, and the height of contour points relative to the fitted line is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Let the coefficient of the linear term (slope) of the locally fitted line based on the least squares method be

, the constant term (intercept) be

, and the distance from the th contour point within the local region to the fitted line be

. This leads to the following:

where

denotes the distance from the i-th contour point to the fitted straight line;

represents the index of the i-th contour point;

denotes the height of the i-th contour point.

Let the local surface roughness at the j-th point on the hard bottom layer be denoted as

, calculated using the following formula:

where

represents the sample size within the specified range.

By performing a traversal calculation on the hard bottom contour collected from the field according to Equation (19), the continuous surface roughness characteristic values of the hard bottom contour traversed by the agricultural machinery can be obtained.

2.2.3. Correlation Impact Analysis Method

When agricultural machinery performs path-following operations, the degree of deviation in vehicle posture from the planned path serves as a key parameter for evaluating the operational quality of autonomous agricultural machinery and determining decision-control output. To analyze how the motion state parameters and hard bottom layer contour feature parameters of agricultural machinery affect the deviation of its posture from the planned path, real-time position and heading are obtained via GNSS. These are then compared with the expected values of the planned path to derive the perpendicular distance between the vehicle position and the expected path (lateral deviation) and the angular difference between the vehicle direction and the expected path direction (heading deviation). Schematic diagrams of lateral deviation and heading deviation are shown in

Figure 7.

The installed GNSS and AHRS systems continuously capture real-time position and attitude parameters of the agricultural machinery, including antenna elevation, velocity, heading angle, pitch angle, and roll angle. Building upon the sensor-derived data, the agricultural machinery operational motion state parameter extraction method described in

Section 2.2.1 is employed. Through Euler transformation, the following motion state parameters are obtained: the bottom of left wheel velocity, the bottom of right wheel velocity, the bottom of left–right wheel velocity difference, left wheel base acceleration, right wheel base acceleration, left–right wheel base acceleration difference, vehicle center velocity, and vehicle center acceleration.

Section 2.2.2’s hard bottom layer contour feature extraction method is used to obtain the 3D coordinates of contact points between the agricultural machinery and the hard bottom layer contour, along with local elevation differences and surface roughness characteristics. A segmented straight working path was selected. Continuous datasets synchronously collected by the vehicle-mounted autonomous driving system—including vehicle pose sensors and operational parameters—were used as the test dataset. Numerical sets for hard bottom layer contour features and agricultural machinery pose parameters were calculated. The lateral deviation and heading deviation recorded during operation were analyzed in relation to the hard bottom layer contour feature parameters and agricultural machinery pose parameters, respectively. To quantify the linear correlation strength and direction between hard bottom layer contour features and agricultural machinery motion parameters as multivariate pairwise continuous variables, this study employs the classical Pearson correlation analysis method. This method calculates the correlation coefficient between each pair of variables by computing the ratio of the covariance between the agricultural machinery motion parameters and the hard bottom layer contour feature parameters to their respective standard deviations multiplied by the position deviation and heading deviation. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the equation, denotes the sequence number of the variable type representing the contour feature parameter of the hard bottom layer for agricultural machinery motion parameters; denotes the sequence number of the deviation type for agricultural machinery motion; denotes the correlation coefficient between the two variables; denotes the covariance between the and variables; and denote the standard deviations of the and variables, respectively.

The correlation coefficient ranges from −1 to 1, where 0 indicates no linear relationship between two variables, 1 indicates perfect positive correlation, and −1 indicates perfect negative correlation. By observing the degree of correlation, significant factors influencing lateral deviation and heading deviation during agricultural machinery movement are analyzed and extracted. Based on the identified significant factors, field experiments are conducted to analyze how the hard bottom layer contour characteristics affect the position and orientation of agricultural machinery.

2.3. Extraction of Agricultural Machinery States During Typical Bogging Processes

During paddy field operations, agricultural machinery often becomes bogged down in mud or soft soil while maneuvering at field edges or working on an unknown hard bottom layer. Unable to extricate itself, the vehicle becomes stuck, severely reducing operational efficiency. This issue is particularly critical during unmanned intelligent farming operations, as it necessitates halting the work program and disrupting continuous operation. Field observations during the application and promotion of intelligent farm machinery in paddy fields reveal that vehicle trapping predominantly occurs when the destruction of the hard bottom layer increases wheel trapping depth. Farm machinery wheels become embedded in this layer, unable to extricate themselves through their own propulsion. This typical type of paddy field trapping is related to the depth and local characteristics of the hard bottom layer. A schematic illustration of vehicle trapping is shown in

Figure 8.

To analyze the typical vehicle-trapping process of agricultural machinery under hard bottom layer conditions, operational data from production trials exhibiting typical trapping scenarios were extracted for analysis. A digital model of the hard bottom layer in the trapping field was constructed using a hard bottom layer digital modeling method. Based on typical bogging incidents occurring during actual agricultural machinery operations, the hard bottom layer contour was captured and its characteristic parameters were extracted using the method described in

Section 2.2.2. This process yielded a localized contour model of the hard bottom layer and its characteristic parameters under typical bogging conditions. The resulting bogging contour model and its locally magnified region are shown in

Figure 9.

To analyze the dynamic characteristics of the hard bottom layer contour before and after the agricultural machinery becomes stuck, the contour feature parameters of the hard bottom layer were extracted from data collected within 15 s before and after the incident. The data system was configured with a sampling frequency of 10 Hz, enabling the extraction of 300 datasets for analysis. The study focused on the contour height at the tire-hard bottom layer interface and the local roughness of the hard bottom layer. Through numerical analysis, a dynamic variation model of the hard bottom layer contour characteristics under typical trapping scenarios was constructed.

2.4. Test Scenario

2.4.1. Paddy Field Operation Test Scenario

An unmanned direct-seeding machine was deployed in rice fields (soil type: sandy loam) at Guangzhou’s Zengcheng District unmanned farm. The machine integrated agricultural machinery position and attitude data, and a hard bottom layer information collection system was integrated into the unmanned rice direct seeder to collect real-time position and attitude data. Utilizing hard bottom layer contour acquisition and feature extraction methods, corresponding contour information was synchronously obtained during machinery movement. The unmanned rice direct seeder performed automated mechanical seeding while concurrently collecting hard bottom layer and mud surface data. The planned working path of the direct seeder is shown in

Figure 10a, and the operational site is depicted in

Figure 10b.

2.4.2. Hard Road Surface Test Scenario

Furthermore, to analyze the impact of agricultural machinery movement when traveling along a hard bottom layer contour with a known fixed elevation difference, two sets of 5 cm high trapezoidal ridges and two sets of 10 cm high trapezoidal ridges were laid at equal intervals along the planned agricultural machinery track on a hard cement road. Using automatic straight-line driving mode, the machinery’s single-side wheels directly rolled over the ridges, causing lateral tilt. The machinery’s position and orientation data were collected to analyze the impact of fixed-height ground contours on its posture through experimental evaluation. The experimental setup is illustrated in

Figure 11, while the actual field test site is shown in

Figure 12.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Relationship Between Agricultural Machinery Movement State and Hard Bottom Layer Characteristic Parameters

3.1.1. Correlation Analysis Results

During paddy field operation trials, the contour characteristics of the paddy field hard bottom layer and the impact of agricultural machinery movement were analyzed. Data collected from paddy field operation scenarios were selected and segmented into straight operation path segments. A dataset comprising 3091 sets of synchronously collected data from vehicle-mounted position and attitude sensors and operation parameters via the vehicle-mounted autonomous driving system was used as the test dataset. Employing the parameter extraction method described in

Section 2.2, the parameter sets for hard bottom layer contour characteristics and agricultural machinery attitude were calculated. These parameters were then analyzed against lateral deviation and heading deviation data collected during operations, with results presented in

Table 1.

Based on Pearson correlation analysis and significance testing results, the strength and direction of statistical correlations between hard bottom contour parameters and agricultural machinery motion parameters were identified. Results indicate that during straight-line operations, both lateral deviation and heading deviation of the agricultural machinery exhibit extremely significant correlations with the Z-axis height of the hard bottom layer contour contacted by the left and right wheel bases and their height differences. They also show extremely significant correlations with the local roughness of the hard bottom layer contour. Additionally, lateral deviation exhibits an extremely significant correlation with the linear speed difference between the left and right wheel bases. The Pearson correlation analysis results reflect the statistical relationship between hard bottom contour characteristics and the agricultural machinery’s posture. They reveal the coupling characteristics and shared dependencies among the agricultural machinery’s motion response parameters under hard bottom excitation conditions, providing quantitative references for subsequent analysis of the agricultural machinery’s posture response mechanisms.

3.1.2. Results of Straight-Line Driving Test on Rigid Pavement with Fixed Elevation Difference

(1) Fixed Wheel Angle Through-the-Ridge Test

Using the fixed wheel angle of agricultural machinery during straight-line travel, a continuous ridge-crossing test was conducted. By obtaining rear wheel center trajectory data, the heading and heading change rate of a single-wheel crossing ridges were analyzed. The front wheels of the rice transplanter’s mobile chassis had a diameter of 0.65 m, while the rear wheels measured 0.95 m in diameter. The speed was set to the field operation speed of 1 m/s. The front and rear wheels traversed two 5 cm high ridges and two 10 cm high ridges, respectively, comprising a total of eight stages designated as A-1, B-1, A-2, B-2, C-1, D-1, C-2, and D-2. The planar trajectory of the agricultural machinery traversing the ridge platform during all stages is shown in

Figure 13a, while the heading changes are depicted in

Figure 13b. Simultaneously, the heading and heading change rate during the machinery’s passage over the ridge platform were acquired, with the results presented in

Figure 14. The stage numbers and descriptions for the entire test process are detailed in

Table 2.

As shown in

Figure 13 and

Table 2, the trajectory tracking results for single-wheel crossing of ridges indicate that when both front and rear wheels continuously traverse a ridge, the agricultural machinery’s heading persistently deviates toward the side with the ridge. The heading variation range when crossing a 5 cm ridge was 0.48–0.85°, while crossing a 10 cm ridge resulted in a variation range of 1.17–2.40°. The heading change caused by a 10 cm obstacle was 2–3 times that of a 5 cm one, indicating that ridge height is the primary influencing factor—consistent with the correlation analysis results.

As shown in

Figure 14 and

Table 2, from the perspective of heading change rate, the front wheel (diameter 0.65 m) exhibited an average heading change rate of 7.48°/s when traversing a 5 cm obstacle, while the rear wheel (diameter 0.95 m) averaged 6.53°/s. This indicates a reduction of approximately 12.6% in the rear wheel’s heading change rate compared to the front wheel. When traversing a 10 cm ridge, the front wheel exhibited a phase-average heading rate of 13.23°/s, while the rear wheel recorded 9.02°/s, indicating a reduction of approximately 31.8% in the rear wheel’s heading rate compared to the front wheel. Larger-diameter wheels demonstrate greater stability when traversing ridges than smaller wheels, a characteristic that becomes more pronounced when navigating higher ridges.

A regression model was developed with ridge height and wheel diameter as independent variables, and the heading change as the dependent variable:

where

represents the heading change value,

represents the ridge height, and

represents the wheel diameter.

The regression model’s coefficient of determination R

2 is 0.92356, with a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.195°, mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.189°, and sum of squared errors (SSEs) of 0.30436. The comparison between actual heading changes and predicted heading changes is shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 15.

To further observe the dynamic process of height differences and the rate of change between the left and right rear axles of agricultural machinery caused by the ridge, the height differences and their rates of change at each pass stage were extracted, as shown in

Figure 16.

As shown in

Figure 16, whether traversing a 5 cm or 10 cm ridge, the front wheels exhibit minimal impact on the rear axle height difference (within 1 cm). However, when the rear wheels pass over the ridge, the rear axle height difference closely matches the ridge height, measuring 5.5 cm, 5.9 cm, 10.6 cm, and 10.8 cm, respectively. Therefore, the front suspension system effectively counteracts terrain effects on the vehicle body when the front wheels traverse the ridges. The rear axle, lacking suspension damping, perceives the actual contour features of the hard subsoil layer when the rear wheels pass over it. The primary factor influencing the roll attitude of the agricultural machinery lies in the terrain characteristics encountered during rear-wheel traversal. Consequently, when considering control compensation for the machinery, the focus should be on the rear wheels and the terrain features they encounter during passage.

(2) Straight-Line Autonomous Driving Ridge-Crossing Test

During straight-line autonomous driving trials on ridges, the agricultural machinery traversed four ridges of identical specifications using straight-line-assisted driving. Using the sensor data calibration method [

18], the roll system error was determined to be −2.429°, the pitch system error was 0.846°, and the heading system error was −1.103°. The positioning antenna, rear axle center, and bottom wheel tracks of the agricultural machinery are shown in

Figure 17.

Based on the acquired positioning data, analyze the deviation of the antenna from the expected path as the agricultural machinery passes through each ridge. Combined with the acquired vehicle posture data, determine the deviation of the center of the rear axle and the center of the line connecting the bottom of left and right wheels from the expected path. The acquired antenna trajectory and its lateral deviation are shown in

Figure 18. The acquired rear axle center trajectory and its lateral deviation are shown in

Figure 19. The acquired centerline trajectory of the bottom of left and right wheels and its lateral deviation are shown in

Figure 20.

Results indicate that when traversing a 5 cm ridge section, the standard deviation of antenna lateral deviation was 0.0143 m, the standard deviation of rear axle center lateral deviation was 0.0109 m, and the standard deviation of left/right wheel base center lateral deviation was 0.0108 m. When traversing the 10 cm ridge section, the standard deviation of antenna lateral deviation was 0.0200 m, the standard deviation of rear axle center lateral deviation was 0.0107 m, and the standard deviation of left/right wheel base center lateral deviation was 0.0112 m. During the entire passage over 5 cm and 10 cm ridges, the standard deviation of the antenna lateral deviation was 0.0182 m, the standard deviation of the rear axle center lateral deviation was 0.0108 m, and the standard deviation of the left and right wheel base center lateral deviation was 0.0111 m. Detailed information is shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 21.

As shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 21, when the agricultural machinery traversed 5 cm and 10 cm ridges, respectively, the standard deviation of the positioning antenna lateral deviation increased from 0.0143 m to 0.0200 m—nearly doubling. Meanwhile, the standard deviation of the lateral for the attitude-corrected rear axle center and bottom of the wheel center remained virtually unchanged at approximately 0.01 m. This indicates that single-side passage over ridges causes lateral displacement of the higher-positioned antenna, while the machine itself does not experience lateral slip. The attitude-corrected rear axle center and bottom of the wheel center more accurately represent the machine’s true real-time position and its actual deviation from the planned path.

The lateral roll angle generated by the height difference between the left and right wheels of the agricultural machinery can be visualized from the rear view as the machinery rotates about the center point O at the base of the left and right wheels, as shown in

Figure 22.

Based on geometric relationships, the theoretical model for the antenna position deviation relative to the horizontal plane during agricultural machinery rollover is as follows:

In the equation, represents the vehicle roll angle caused by the height difference between the left and right wheels, denotes the height difference between the left and right wheels, indicates the rear track width of the agricultural machinery, shows the offset of the antenna position relative to the horizontal plane during roll, is the height of the antenna above the bottom of wheel, and is the symmetrical mounting distance between the dual antennas.

From the theoretical model Equation (20) and numerical results (

Table 4 and

Figure 22) for antenna position deviation relative to horizontal during the entire process of agricultural machinery rolling over ridges, it can be observed that the hard bottom layer contour significantly affects the lateral deviation of the positioning antenna. The deviation of the antenna position from horizontal during machine rollover is proportional to the height difference between left and right wheels and the installation height of the antenna relative to the bottom of wheel. Specifically, when the machine rolls 1.91 degrees and 3.81 degrees over the tested 0.05 m and 0.1 m high ridges, the antenna position deviates 0.083 m and 0.166 m from the horizontal, respectively. After attitude correction calculations, the lateral deviation accuracy of the rear axle center and left/right wheel bottom centers relative to the positioning antenna improved by 40.7% and 39.0%, respectively.

3.2. Analysis of the Impact of the Paddy Field Hard Bottom Layer on Typical Agricultural Machinery Bogging Incidents

During paddy field operation trials, data on the hard bottom layer contour and agricultural machinery attitude were extracted during the process of machinery becoming stuck due to hard bottom layer depression. To analyze the complete process of becoming stuck, data from 15 s before and after the incident were extracted for analysis. The surface points of the extracted hard bottom layer contour are shown in

Figure 23.

Referring to the correlation analysis results in

Section 3.1.1, under unmanned operation conditions, the positional deviation of agricultural machinery exhibits extremely significant correlations with both the hard bottom layer height and the local roughness of the hard bottom layer contour surface. This section analyzes the hard bottom layer height and local roughness across 300 datasets collected before and after vehicle trapping. The relationship between hard bottom layer height and local roughness changes during the 15 s preceding and following trapping is illustrated in

Figure 24.

To visually illustrate the changes in the hard bottom layer contour and surface roughness before and after vehicle trapping, contour points of the hard bottom layer and local contour points were plotted at 0.1 s intervals over a 30 s period before and after trapping. Fitted straight lines were then calculated for local roughness, as shown in

Figure 25.

As shown in

Figure 24 and

Figure 25, during the normal operation segment (−15 s to −5 s) in paddy fields, the average elevation of the hard bottom layer contour tends to stabilize. Adjacent local contour fitting lines exhibit an alternating pattern, with the local roughness of the hard bottom layer contour fluctuating between 0.002 and 0.008. During the pre- and post-vehicle-trapping segments (−5 s to 5 s), as the vehicle approaches a low-lying area, the hard bottom contour elevation drops sharply. Adjacent local contour fitting lines exhibit a rapid downward shift, and the local roughness of the hard bottom contour increases dramatically. At the moment of initial trapping (“0 s”), the local roughness value peaks at 0.0125. During the post-trapping phase (5 s–15 s), the slip ratio between the agricultural machinery wheels and the hard base layer increases to pure sliding. The contour elevation of the hard base layer decreases gradually, and the adjacent local contour fitting lines exhibit a slow downward shift. The local roughness of the hard base layer contour decreases sharply, with the local roughness value dropping to 0.0014, approaching the 0.0011 value observed during idle parking.

Based on changes in contour elevation and local roughness, construct segmented discriminant functions for pre- and post-wheel-trapping states. Let the agricultural machinery’s motion state at time

be

, the hard bottom layer elevation change rate be

, and the local roughness be

. The local roughness change rate is

, the upper threshold for roughness is

, the contour height change rate threshold is

. This leads to the following:

Based on

Figure 24 and

Figure 25 and the segmented vehicle-trapping discrimination function (24), it is evident that in typical vehicle-trapping scenarios on paddy fields, when a decline in the hard bottom contour is detected alongside a sharp increase in local roughness, exceeding the upper threshold of 0.01, the agricultural machinery faces a risk of trapping. When a decrease in the hard bottom contour is detected alongside a decrease in local roughness values, it indicates that the agricultural machinery has become trapped. This provides a basis for predicting trapping incidents caused by hard bottom depressions in paddy fields and for designing post-trapping recovery strategies.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the influence patterns of hard bottom layer contours on the position and attitude changes in agricultural machinery. By integrating GNSS and AHRS sensors, a system for collecting position/attitude and hard bottom layer information was established, revealing the mechanism by which typical paddy field terrain features affect the attitude response of unmanned agricultural machinery during operation. The findings indicate that the geometric characteristics and local roughness parameters of the hard bottom contour significantly influence the heading stability, lateral stability, attitude changes, and trapping risk of agricultural machinery. This research provides crucial theoretical and technical support for path planning and driving control in unmanned precision agricultural operations.

The proposed method for acquiring hard bottom contour data and integrating pose information achieves the acquisition and fusion of motion state data from multiple key points (antenna, wheel bottom, rear axle center) by mounting GNSS and AHRS on the power chassis of a rice transplanter. This provides a foundation for dynamic analysis of agricultural machinery’s attitude response characteristics. The study reveals the influence patterns of ridge height and local roughness variations on heading deviation and attitude response, providing a basis for speed control and path tracking of agricultural machinery in complex terrain. Notably, the finding that a 10 cm ridge causes two to three times greater heading deviation than a 5 cm ridge indicates that terrain undulations significantly impact path accuracy in autonomous agricultural machinery. Large-diameter tires effectively mitigate this effect, offering a mechanical design approach to enhance driving stability.

Additionally, previous studies have directly analyzed operational status based on single GNSS or GNSS/IMU fusion results. In challenging environments like paddy fields with pronounced undulations on hard bottom layers, agricultural machinery experiences frequent roll and pitch attitude changes. Without attitude correction, this can introduce systematic errors. This research introduces attitude correction to compensate for key task parameters, effectively mitigating the impact of attitude disturbances on task accuracy under complex operating conditions. After correcting the positional deviations of the rear axle center and bottom-of-the-wheel center using the attitude correction algorithm, the lateral deviation accuracy improved by approximately 40% compared to antenna measurements. This demonstrates the feasibility and necessity of the attitude fusion correction algorithm for enhancing positioning accuracy. These findings provide practical guidance for optimizing attitude solution models and improving multi-sensor fusion algorithms in unmanned agricultural machinery.

The results of the vehicle-trapping test indicate that when the hard bottom contour drops sharply within a short time and the roughness increases to 0.01, agricultural machinery is prone to trapping. This validates that the hard bottom contour parameters can serve as key indicators for predicting trapping risk and establishes a segmented discrimination function for trapping states. This provides criteria for establishing pre-trapping warnings and escape strategies during unmanned operations. By integrating real-time hard bottom contour change rate and roughness threshold parameters into the autonomous control system, adaptive adjustments to speed and posture response strategies can be achieved during operations, thereby enhancing operational safety and continuity.

However, since the experimental platform utilizes a rice transplanting power chassis, the stiffness and vibration characteristics of the sensor mounting location exert a certain influence on measurement accuracy under bumpy terrain conditions. Future improvements in data stability can be achieved through structural optimization and high-precision attitude fusion algorithms. The hard bottom contour sampling and data processing in this study remain offline procedures. Integrating real-time data streams for dynamic modeling and feature recognition could enable online assessment and adaptive control of agricultural machinery operation status, representing a key direction for future research. Additionally, vehicle trapping during the planting phase is most frequent in paddy field operations, commonly occurring in typical rice transplanters with power-driven chassis similar to those studied here. To ensure transplanting or direct-seeding quality, operating speeds are typically maintained around 1 m/s. Field tests validated the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed method under typical paddy field conditions. Further validation tests will be conducted at varying speeds across multiple wheeled and tracked agricultural machinery platforms, as well as in paddy fields with different regional characteristics, soil textures, and moisture content levels. This will systematically assess the method’s versatility and robustness while continuously refining the model’s applicability. This represents a key direction for future research.

In summary, the proposed method for analyzing the influence of hard bottom contours on the position and attitude changes in agricultural machinery not only provides a theoretical basis for revealing the relationship between terrain and the dynamic response of agricultural machinery, but also offers technical references for unmanned precision operation path planning, vehicle trapping early warning, and agricultural machinery structural optimization. This holds significant importance for advancing the autonomous perception and intelligent decision-making capabilities of smart agricultural machinery systems.

5. Conclusions

To reveal the influence patterns of hard bottom contour on changes in the position and attitude of agricultural machinery during operation, this study utilizes a rice transplanter chassis equipped with GNSS and AHRS to establish a platform for synchronous acquisition of agricultural machinery position/attitude data and hard bottom contour information. It proposes a method for analyzing the correlation between operational movement states and contour feature parameters, revealing the influence patterns of hard bottom contour characteristics on agricultural machinery attitude response and the mechanism of vehicle entrapment. Key findings include the following:

(1) A platform for acquiring agricultural machinery pose information and hard bottom surface contour features was established. Through multi-sensor fusion of GNSS and AHRS, continuous collection of agricultural machinery operating status and parameters such as hard bottom elevation and local roughness was achieved, ensuring high-precision data acquisition and temporal consistency. A pose response model for key components of agricultural machinery was constructed, providing a data foundation for analyzing the coupling relationship between terrain excitation and machinery response.

(2) A correlation analysis method was established between the motion state of agricultural machinery and the contour characteristics of the hardpan layer. Results indicate that hardpan elevation differences and local undulation characteristics are key factors inducing lateral and heading deviations in agricultural machinery. Terrain asymmetry and ridge height variations significantly amplify the heading response of machinery. The resulting heading response model effectively quantifies the relationship between terrain disturbances and machinery motion states, validating the pivotal role of hardpan profile analysis in assessing paddy field driving stability.

(3) This study elucidates the attitude response and correction characteristics of wheeled agricultural machinery during ridge crossing. Under typical ridge-crossing conditions, wheel dimensions and suspension structures significantly influence terrain excitation suppression, with the rear-wheel-over-ridge phase being the primary source of machine roll and abrupt attitude changes. By introducing attitude compensation and motion correction models, positioning accuracy at critical points was effectively enhanced, validating the effectiveness of attitude correction methods under complex terrain conditions.

(4) A vehicle trapping identification and early warning criterion based on dynamic changes in the hard bottom contour was proposed. In typical vehicle-trapping tests, the elevation and local roughness of the hard bottom exhibit phased evolutionary patterns before and after trapping occurs. The vehicle-trapping state discrimination and early warning model established based on this characteristic enables advance identification of typical trapping behavior, providing quantifiable criteria for trapping early warning and escape control.

This study investigates the influence of hard bottom contours on the position and attitude changes in agricultural machinery during movement. It establishes quantitative relationships among hard bottom contour characteristics, agricultural machinery attitude responses, and vehicle-trapping states. The findings provide theoretical foundations and technical support for intelligent path-tracking control, chassis structure optimization, and unmanned precision operations in agricultural machinery. This research holds significant importance for enhancing the intelligence level and operational efficiency of paddy field machinery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T., L.H., X.L. and J.H.; methodology, T.T., L.H., X.L. and J.H.; software, T.T., P.W., P.H., R.Z. and G.C.; validation, T.T., Z.M., D.F. and M.Y.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T. and X.D. (Xianhao Duan); resources, T.T., L.H., X.L., J.H. and P.W.; data curation, T.T., L.H. and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, T.T., L.H., X.L. and J.H.; visualization, T.T., L.H., P.W., X.D. (Xiaobing Deng), and J.M.; supervision, L.H., X.L. and J.H.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, T.T. and L.H. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024M750955), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472016, 32071913), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (Grade C) of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. GZC20230855), and the Lingnan Modern Agricultural Science and Technology Laboratory Independent Research Project (Grant No. NT2025006).

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our partners of the Zengcheng Teaching Base of South China Agricultural University for their help and support in field management and machine maintenance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nawaz, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Increasing sustainability for rice production systems. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 103, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seck, P.A.; Diagne, A.; Mohanty, S.; Wopereis, M.C.S. Crops that feed the world 7: Rice. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzer, C.; Knauer, K. Remote sensing of rice crop areas. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 2101–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, F.; Xiao, X.; Dong, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Zou, Z.; Ma, J.; Du, G.; et al. Large increases of paddy rice area, gross primary production, and grain production in Northeast China during 2000–2017. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 135183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Man, Z.; Tu, T.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Yi, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Path tracking control method and performance test based on agricultural machinery pose correction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hu, L.; He, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liao, J.; Huang, P. Key technologies and practice of unmanned farm in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, T.; He, J.; Luo, X.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; Chen, G.; Tian, L.; Feng, D.; Wang, Z.; Man, Z.; et al. Methods and experiments for collecting information and constructing models of bottom-layer contours in paddy fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, M.G. Introduction to Terrain–Vehicle Systems; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.Y. Theory of Ground Vehicles, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Smith, W.; Peng, H. Terramechanics-based wheel–terrain interaction model and its applications to off-road wheeled mobile robots. Robotica 2012, 30, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misaghi, S.; Tirado, C.; Nazarian, S.; Carrasco, C. Impact of pavement roughness and suspension systems on vehicle dynamic loads on flexible pavements. Transp. Eng. 2021, 3, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Li, A.; Feng, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qin, D.; Ge, S. Influence of the driving environment on the dynamic characteristics of a DCT vehicle starting considering the longitudinal and vertical coupling model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inotsume, H.; Kubota, T. Terrain traversability prediction for off-road vehicles based on multi-source transfer learning. ROBOMECH J. 2022, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golanbari, B.; Mardani, A.; Hosainpour, A.; Taghavifar, H. Predicting terrain deformation patterns in off-road vehicle-soil interactions using TRR algorithm. J. Terramechanics 2025, 117, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Luo, X.; Hu, L.; Chung, S.; He, J.; Zhao, R.; Wang, P.; Chen, G.; Feng, D.; Yue, M.; et al. Methods and experiments for analysing hard-bottom layer changes and monitoring wheel sink depth in paddy fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 238, 110760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenain, R.; Thuilot, B.; Cariou, C.; Martinet, P. High accuracy path tracking for vehicles in presence of sliding: Application to farm vehicle automatic guidance for agricultural tasks. Auton. Robot. 2006, 21, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A. Using GPS for Model Based Estimation of Critical Vehicle States and Parameters. Doctoral Dissertation, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bevly, D.M.; Gerdes, J.C.; Wilson, C.; Zhang, G. The use of GPS based velocity measurements for improved vehicle state estimation. In Proceedings of the 2000 American Control Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 28–30 June 2000; pp. 2538–2542. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.; Gerdes, J.C. Integrating inertial sensors with global positioning system (GPS) for vehicle dynamics control. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2004, 126, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, M.L.; Leo, T.; Orlando, G. Experimental testing of a discrete-time sliding mode controller for trajectory tracking of a wheeled mobile robot in the presence of skidding effects. J. Robot. Syst. 2002, 19, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, T.; Nishihara, O.; Kumamoto, H. Automatic path-tracking controller of a four-wheel steering vehicle. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2009, 47, 1205–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucet, E.; Lenain, R.; Grand, C. Dynamic path tracking control of a vehicle on slippery terrain. Control Eng. Pract. 2015, 42, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenain, R.; Thuilot, B.; Cariou, C.; Martinet, P. Mixed kinematic and dynamic sideslip angle observer for accurate control of fast off-road mobile robots. J. Field Robot. 2010, 27, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y. Development of Paddy Field Rotary-leveling Machine Based on GNSS. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, J.; Patel, M.; Atha, D.; Nubert, J.; Fan, D.; Agha, A.; Padgett, C.; Spieler, P.; Hutter, M.; Khattak, S. RoadRunner-Learning Traversability Estimation for Autonomous Off-road Driving. IEEE Trans. Field Robot. 2024, 1, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sten, G.; Feng, L.; Möller, B. Enhancing Off-Road Topography Estimation by Fusing LIDAR and Stereo Camera Data with Interpolated Ground Plane. Sensors 2025, 25, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Platform for collecting agricultural machinery pose information and bottom layer contour data: (a) information collection platform; (b) data collection process.

Figure 1.

Platform for collecting agricultural machinery pose information and bottom layer contour data: (a) information collection platform; (b) data collection process.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing the relationship between the local cutting plane coordinate system {t}, the vehicle body coordinate system {b}, and the position of the rear bottom of the wheel of the vehicle body.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing the relationship between the local cutting plane coordinate system {t}, the vehicle body coordinate system {b}, and the position of the rear bottom of the wheel of the vehicle body.

Figure 3.

The positional relationship during body pitch: (a) rear view during vehicle pitching; (b) left view during vehicle pitching.

Figure 3.

The positional relationship during body pitch: (a) rear view during vehicle pitching; (b) left view during vehicle pitching.

Figure 4.

Full-field wheel track pattern.

Figure 4.

Full-field wheel track pattern.

Figure 5.

Hard bottom layer contour curve: (a) segmented trajectory; (b) 3D spline curve fitting.

Figure 5.

Hard bottom layer contour curve: (a) segmented trajectory; (b) 3D spline curve fitting.

Figure 6.

Relationship between hard bottom layer, local fitted line segments, and height of contour points relative to the fitted straight line.

Figure 6.

Relationship between hard bottom layer, local fitted line segments, and height of contour points relative to the fitted straight line.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of lateral deviation and heading deviation in agricultural machinery. Note: In the figure, represents the target heading angle, denotes the heading angle deviation, and indicates the lateral position deviation. The target navigation line is formed by points and , with serving as the target navigation point.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of lateral deviation and heading deviation in agricultural machinery. Note: In the figure, represents the target heading angle, denotes the heading angle deviation, and indicates the lateral position deviation. The target navigation line is formed by points and , with serving as the target navigation point.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of a typical vehicle-trapping process: (a) normal driving; (b) about to be trapped; (c) just trapped; (d) after being trapped.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of a typical vehicle-trapping process: (a) normal driving; (b) about to be trapped; (c) just trapped; (d) after being trapped.

Figure 9.

Digital model of hard bottom layer in fields where vehicle trapping occurred.

Figure 9.

Digital model of hard bottom layer in fields where vehicle trapping occurred.

Figure 10.

Planned driving path and field site of unmanned direct seeding machine: (a) planned driving path; (b) field site.

Figure 10.

Planned driving path and field site of unmanned direct seeding machine: (a) planned driving path; (b) field site.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of hard road surface testing.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of hard road surface testing.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of hard road surface test: (a) driving over a 5 cm high trapezoidal ridge; (b) driving over a 10 cm high trapezoidal ridge.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of hard road surface test: (a) driving over a 5 cm high trapezoidal ridge; (b) driving over a 10 cm high trapezoidal ridge.

Figure 13.

Trajectory curve and heading change rate of agricultural machinery: (a) trajectory of agricultural machinery traversing ridge platforms; (b) heading changes during agricultural machinery traversal of ridge platforms.

Figure 13.

Trajectory curve and heading change rate of agricultural machinery: (a) trajectory of agricultural machinery traversing ridge platforms; (b) heading changes during agricultural machinery traversal of ridge platforms.

Figure 14.

Heading and heading change rate during the process of agricultural machinery traversing ridge platforms.

Figure 14.

Heading and heading change rate during the process of agricultural machinery traversing ridge platforms.

Figure 15.

Comparison between measured and model-predicted heading change values: (a) numerical comparison; (b) residual plot.

Figure 15.

Comparison between measured and model-predicted heading change values: (a) numerical comparison; (b) residual plot.

Figure 16.

Dynamic process of height difference between left and right rear axles and its rate of change.

Figure 16.

Dynamic process of height difference between left and right rear axles and its rate of change.

Figure 17.

Track of the main positioning antenna, rear axle center, and wheel track.

Figure 17.

Track of the main positioning antenna, rear axle center, and wheel track.

Figure 18.

Antenna trajectory and its lateral deviation: (a) antenna trajectory; (b) antenna lateral deviation.

Figure 18.

Antenna trajectory and its lateral deviation: (a) antenna trajectory; (b) antenna lateral deviation.

Figure 19.

Center trajectory of the rear axle on agricultural machinery and its lateral deviation: (a) center trajectory of agricultural machinery rear axle; (b) lateral deviation of agricultural machinery rear axle center.

Figure 19.

Center trajectory of the rear axle on agricultural machinery and its lateral deviation: (a) center trajectory of agricultural machinery rear axle; (b) lateral deviation of agricultural machinery rear axle center.

Figure 20.

Center trajectory of the line connecting the left and right wheel bottoms and its lateral deviation; (a) center trajectory of wheel base connection lines; (b) lateral deviation of wheel base connection line center.

Figure 20.

Center trajectory of the line connecting the left and right wheel bottoms and its lateral deviation; (a) center trajectory of wheel base connection lines; (b) lateral deviation of wheel base connection line center.

Figure 21.

Comparison of standard deviations for lateral deviations across different sections.

Figure 21.

Comparison of standard deviations for lateral deviations across different sections.

Figure 22.

Schematic diagram showing antenna position deviation when the agricultural machinery rolls compared to the horizontal position.

Figure 22.

Schematic diagram showing antenna position deviation when the agricultural machinery rolls compared to the horizontal position.

Figure 23.

Surface points of the hard bottom layer 15 s before and after vehicle trapping.

Figure 23.

Surface points of the hard bottom layer 15 s before and after vehicle trapping.

Figure 24.

Relationship between hard substrate height and local roughness changes before and after 30 s trapping: (a) height variation contour of the hard bottom layer contour; (b) local roughness variation contour of the hard bottom layer contour; (c) hard bottom layer contour height variation and local roughness variation curves.

Figure 24.

Relationship between hard substrate height and local roughness changes before and after 30 s trapping: (a) height variation contour of the hard bottom layer contour; (b) local roughness variation contour of the hard bottom layer contour; (c) hard bottom layer contour height variation and local roughness variation curves.

Figure 25.

Changes in hard substrate height and local roughness from 15 s before to 15 s after trapping: (a) −15 s~−10 s; (b) −10 s~−5 s; (c) −5 s~0 s; (d) 0 s~5 s; (e) 5 s~10 s; (f) 10 s~15 s.

Figure 25.

Changes in hard substrate height and local roughness from 15 s before to 15 s after trapping: (a) −15 s~−10 s; (b) −10 s~−5 s; (c) −5 s~0 s; (d) 0 s~5 s; (e) 5 s~10 s; (f) 10 s~15 s.

Table 1.

Correlation analysis between hard bottom layer contour characteristics and agricultural machinery motion parameters.

Table 1.

Correlation analysis between hard bottom layer contour characteristics and agricultural machinery motion parameters.

| Variable | Lateral Deviation (m) | | Heading Deviation (°) | |

|---|

| | Pearson Correlation | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Pearson Correlation | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

|---|

| Hardpan feature parameters | | | | |

| X-coordinate of left wheel–hardpan contact point (m) | −0.042 * | 0.021 | −0.101 ** | 0.000 |

| Y-coordinate of left wheel–hardpan contact point (m) | 0.040 * | 0.026 | 0.101 ** | 0.000 |

| Z-coordinate of left wheel–hardpan contact point (m) | 0.156 ** | 0.000 | 0.056 ** | 0.002 |

| X-coordinate of right wheel–hardpan contact point (m) | −0.042 * | 0.020 | −0.102 ** | 0.000 |

| Y-coordinate of right wheel–hardpan contact point (m) | 0.040 * | 0.025 | 0.102 ** | 0.000 |

| Z-coordinate of right wheel–hardpan contact point (m) | 0.056 ** | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.917 |

| Height difference between left and right wheel contact points (m) | 0.142 ** | 0.000 | 0.075 ** | 0.000 |

| Local roughness of contour | 0.094 ** | 0.000 | −0.118 ** | 0.000 |

| Machinery posture parameters | | | | |

| Speed (m/s) | 0.152 ** | 0.000 | −0.027 | 0.129 |

| Left wheel velocity (m/s) | 0.017 | 0.337 | −0.010 | 0.561 |

| Right wheel velocity (m/s) | 0.152 ** | 0.000 | −0.019 | 0.289 |

| Velocity difference between left and right wheels (m/s) | −0.377 ** | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.180 |

| Left wheel acceleration (m/s2) | −0.002 | 0.913 | −0.013 | 0.458 |

| Right wheel acceleration (m/s2) | 0.006 | 0.732 | 0.012 | 0.493 |

| Acceleration difference between left and right wheels (m/s2) | −0.041 * | 0.021 | −0.131 ** | 0.000 |

| Center velocity (m/s) | 0.088 ** | 0.000 | −0.019 | 0.282 |

| Center acceleration (m/s2) | 0.002 | 0.892 | 0.000 | 0.995 |

Table 2.

Heading variation during ridge crossing.

Table 2.

Heading variation during ridge crossing.

| Stage ID | Description | Heading (°) | Heading Change (°) | Maximum Heading Change Rate (°/s) |

|---|

| A-1 | Front wheel crossing the first 5 cm ridge | −89.15 | 0.85 | 6.694 |

| B-1 | Rear wheel crossing the first 5 cm ridge | −88.66 | 0.49 | 6.039 |

| A-2 | Front wheel crossing the second 5 cm ridge | −87.85 | 0.81 | 8.259 |

| B-2 | Rear wheel crossing the second 5 cm ridge | −87.37 | 0.48 | 7.023 |

| C-1 | Front wheel crossing the first 10 cm ridge | −85.06 | 2.31 | 13.57 |

| D-1 | Rear wheel crossing the first 10 cm ridge | −83.72 | 1.34 | 10.49 |

| C-2 | Front wheel crossing the second 10 cm ridge | −81.32 | 2.4 | 12.88 |

| D-2 | Rear wheel crossing the second 10 cm ridge | −80.15 | 1.17 | 7.552 |

Table 3.

Comparison between actual and predicted heading change values.

Table 3.

Comparison between actual and predicted heading change values.

| Sample No. | Ridge Height (m) | Wheel Diameter (m) | Actual Heading Change (°) | Predicted Heading Change (°) | 95% Confidence Interval (°) |

|---|

| 1 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 1.02 | [0.63, 1.41] |

| 2 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.3 | [−0.09, 0.68] |

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 1.02 | [0.63, 1.41] |

| 4 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.48 | 0.3 | [−0.09, 0.68] |

| 5 | 0.1 | 0.65 | 2.31 | 2.17 | [1.78, 2.55] |

| 6 | 0.1 | 0.95 | 1.34 | 1.44 | [1.06, 1.83] |

| 7 | 0.1 | 0.65 | 2.4 | 2.17 | [1.78, 2.55] |

| 8 | 0.1 | 0.95 | 1.17 | 1.44 | [1.06, 1.83] |

Table 4.

Standard deviations of lateral deviations for different sections.

Table 4.

Standard deviations of lateral deviations for different sections.

| Section | Antenna Lateral Deviation SD (m) | Rear Axle Center Lateral Deviation SD (m) | Rear Wheel Midpoint Lateral Deviation SD (m) |

|---|

| 5 cm Ridge | 0.0143 | 0.0109 | 0.0108 |

| 10 cm Ridge | 0.0200 | 0.0107 | 0.0112 |

| Entire section (5 cm + 10 cm) | 0.0182 | 0.0108 | 0.0111 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |