Hyperspectral Sensing and Machine Learning for Early Detection of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage in Wheat: Insights for Precision Pest Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- data acquisition;

- data analysis;

- ML modeling.

2.1. Data Acquisition

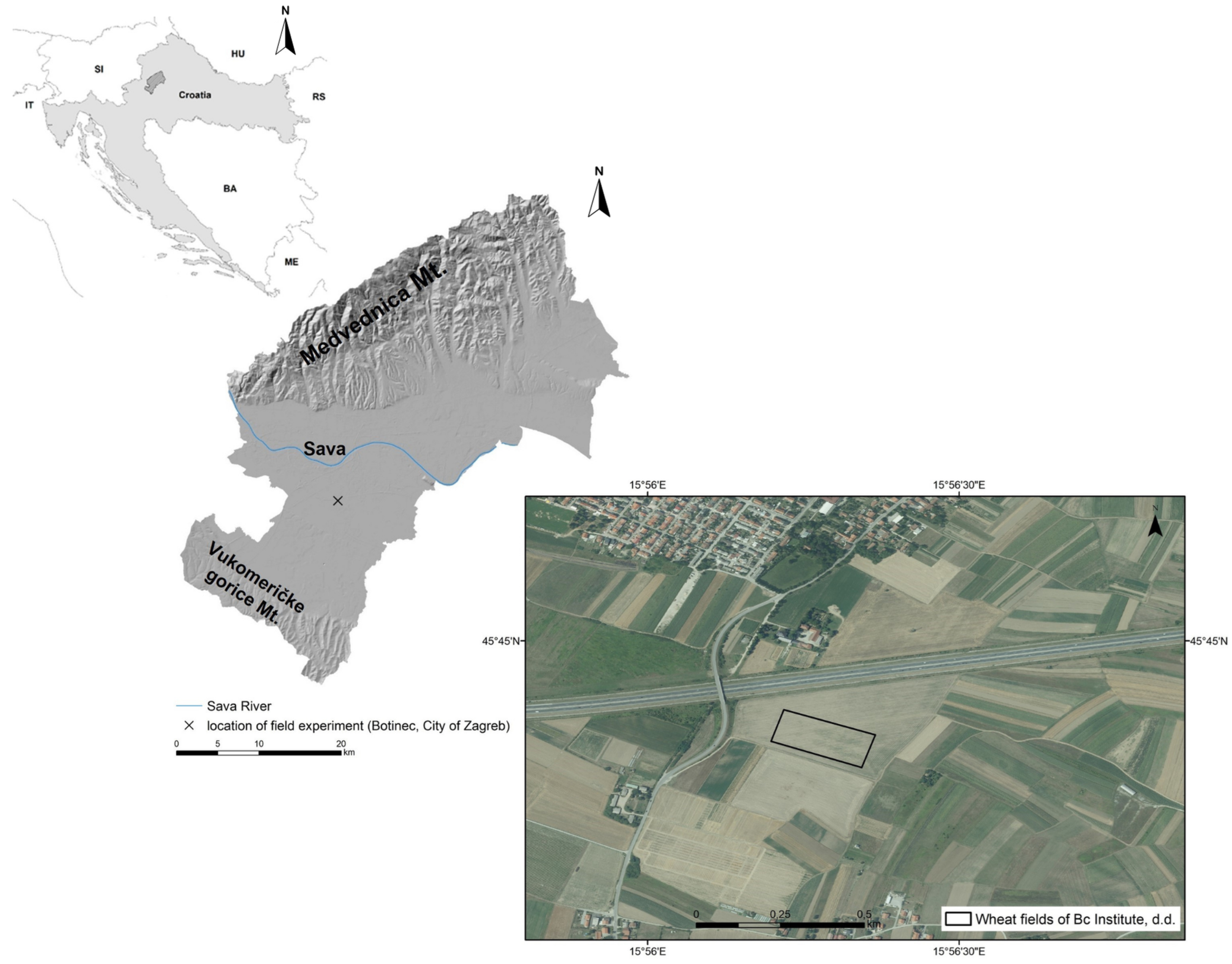

2.1.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

2.1.2. Visual Assessment of Damage on Flag Leaves

- healthy leaf samples with no visible symptoms, representing 0% damage;

- slightly damaged leaves, with 10–15% leaf tissue loss; corresponding to the treatment threshold of 1 larva per flag leaf;

- moderately damaged leaves, exhibiting 15–30% leaf tissue loss, corresponding to the treatment threshold of 2–3 larvae per flag leaf (aligns with central European economic thresholds, where farmers can often tolerate yield losses from damage levels below this threshold);

- severely damaged leaves, showing extensive feeding, with 30–60% leaf tissue loss.

2.1.3. Spectral Data Acquisition

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Data Processing

- Healthy plants: 52;

- Slightly damaged plants: 52;

- Moderately damaged plants: 46;

- Severely damaged plants: 60.

2.2.2. Data Segmentation

Spectral Reflectance Data

Vegetation Indices (VI)

Uniform Manifold Approximation (UMAP)

2.2.3. Visual and Statistical Analysis

2.3. Machine Learning (ML) Analysis

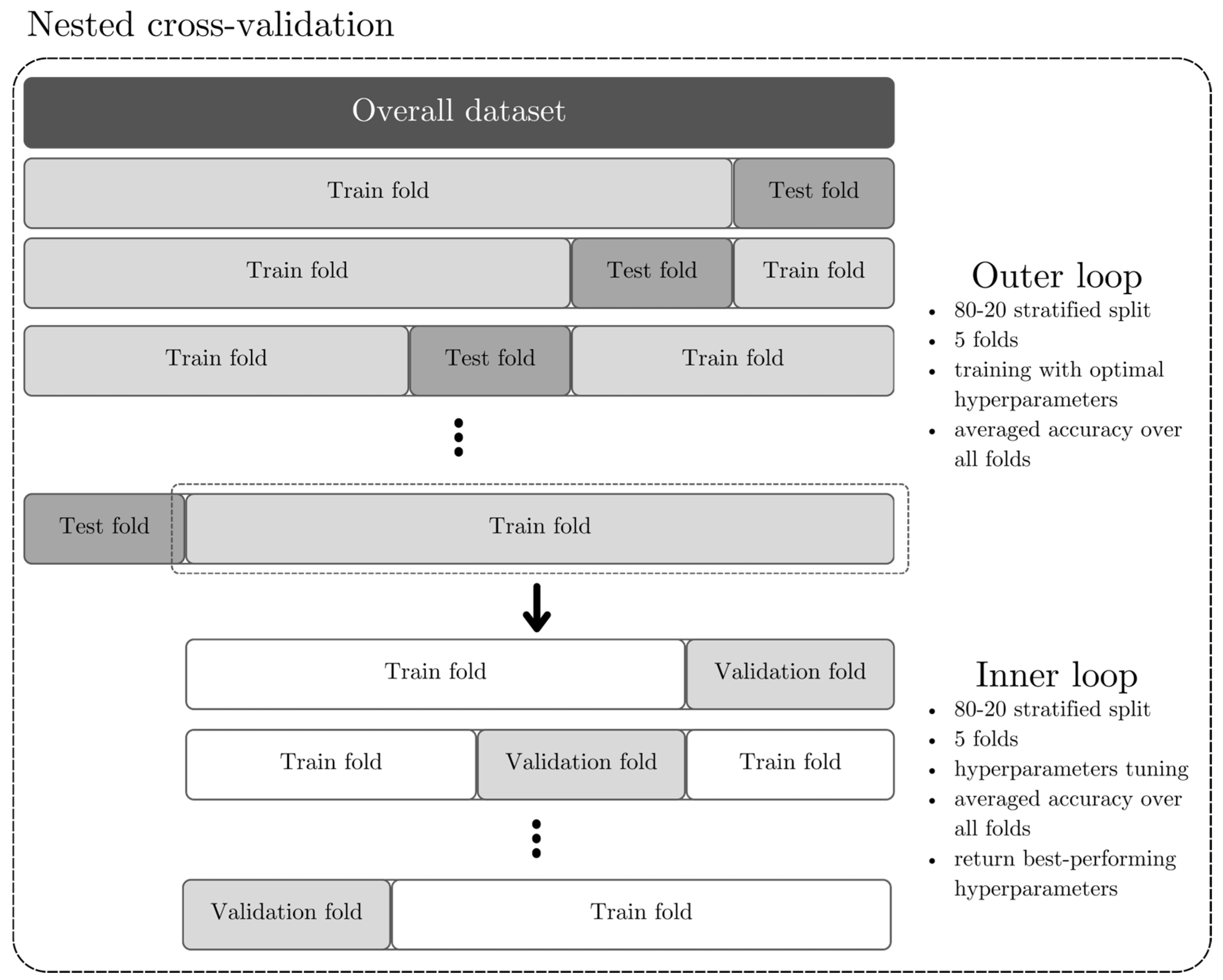

2.3.1. Data Splitting and Processing

2.3.2. Machine Learning Models and Models Training

2.3.3. Models Validation

2.3.4. Feature Importance Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Visual and Statistical Analysis

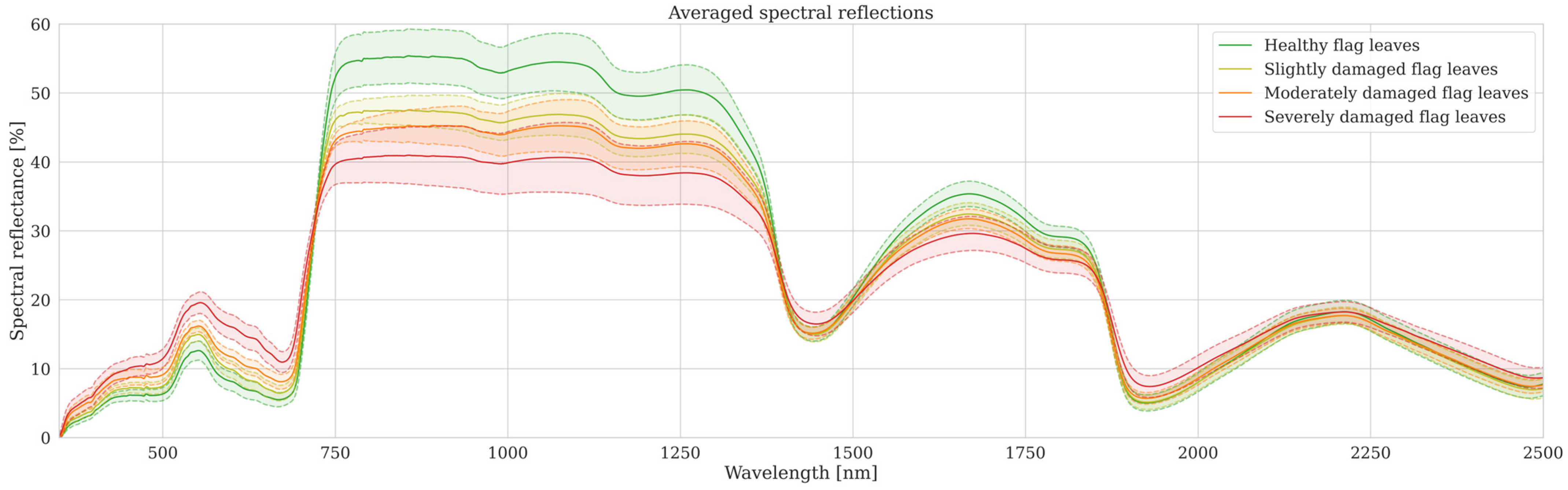

3.1.1. Response of Leaf Reflectance Spectra to CLB Damage

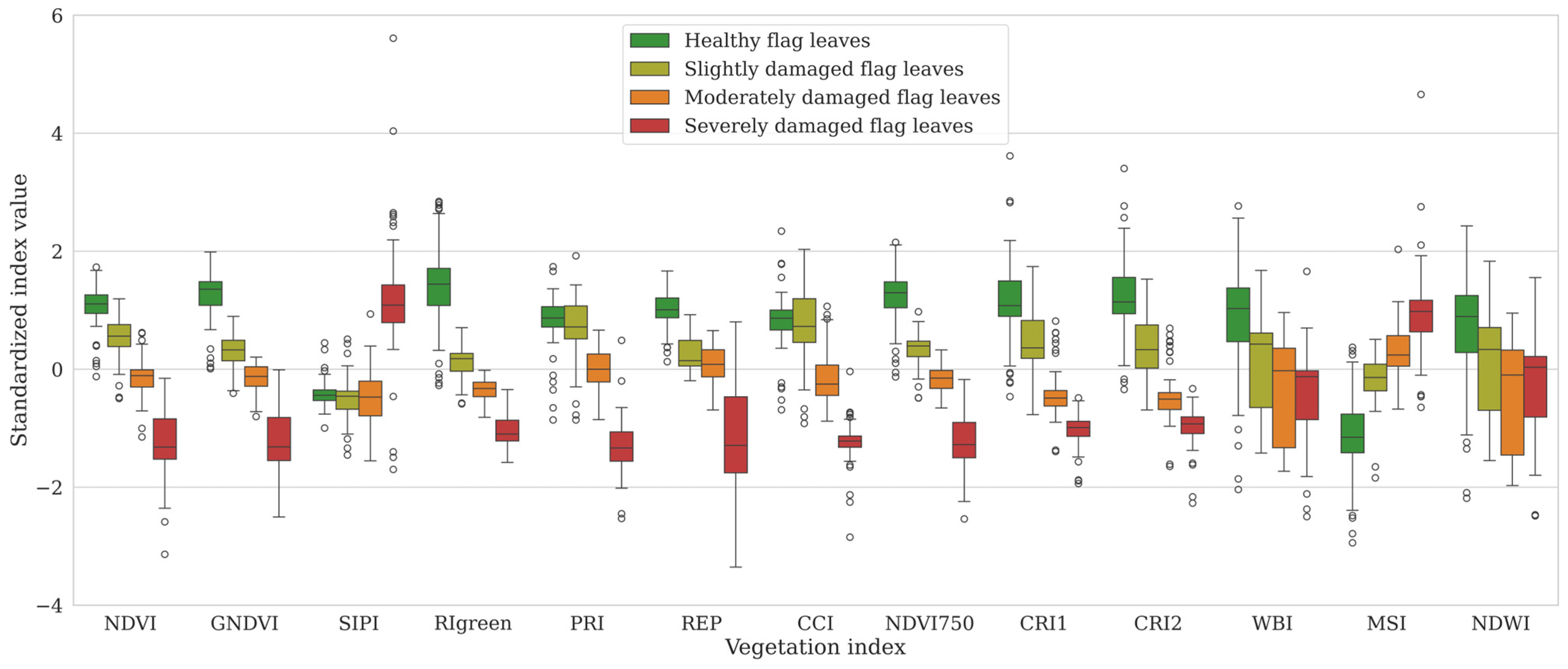

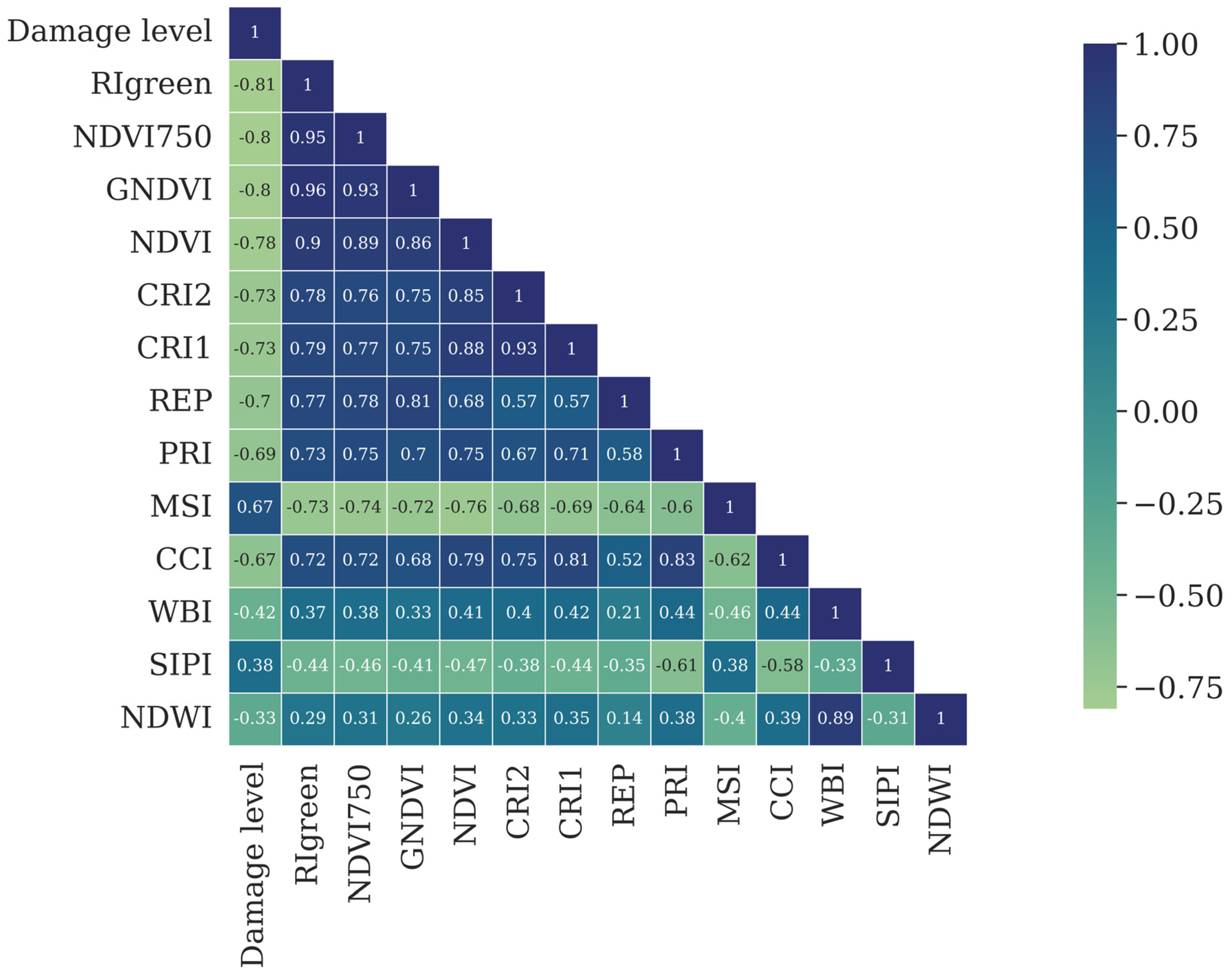

3.1.2. Vegetation Indices (VI)

3.1.3. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) Transformation

3.2. Machine Learning (ML) Modelling

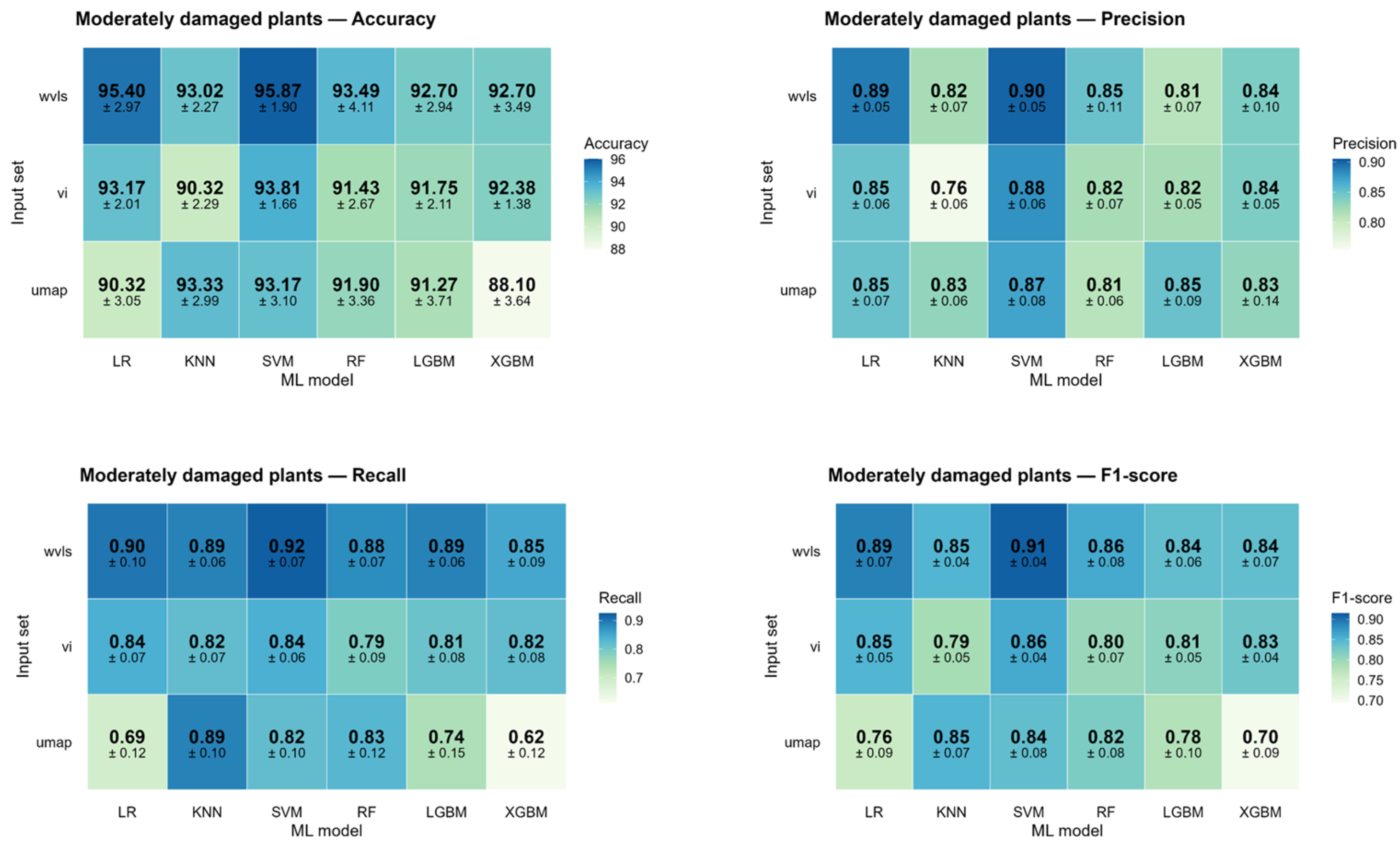

3.2.1. ML Models Validation

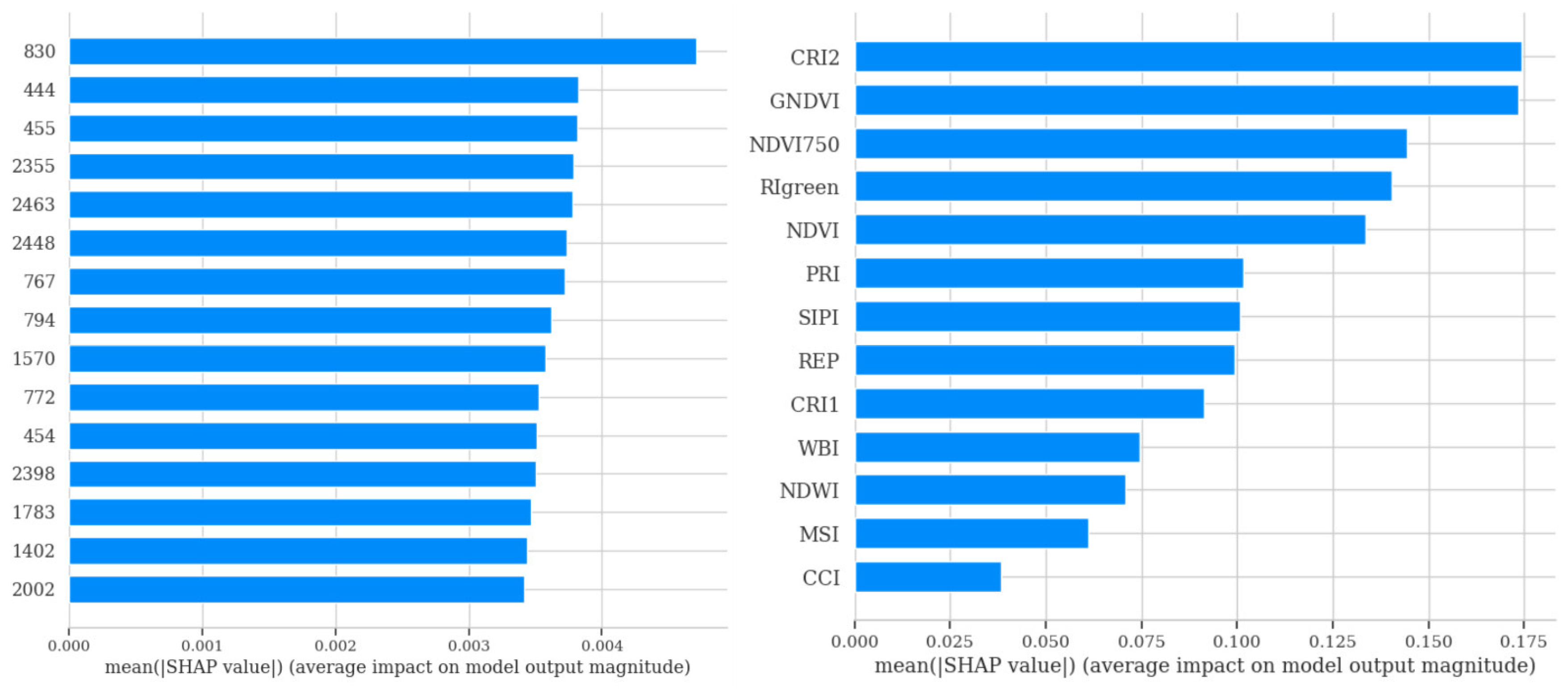

3.2.2. ML Models Feature Importance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLB | Cereal Leaf Beetle |

| ML | Machine learning |

| RS | Remote sensing |

| VI | Vegetation index/indices |

| LR | Linear regression |

| KNN | k-nearest neighbor |

| RF | Random Forest |

| LGBM | Light Gradient-Boosting Machine |

| XGBM | Extreme Gradient Boosting Machine |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

Appendix A. Implementation Aspects

Appendix B

| Model | Hyperparameter | Range |

|---|---|---|

| UMAP | No. of neighbors | [5, 10, 15, 20, 30] |

| Minimum distance | [0.0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5] | |

| Logistic regression | C | [1 × 10−3, 50], uniform distribution in the log domain |

| Tolerance | [1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−3], uniform distribution | |

| Penalty | [l1, l2, elasticnet] | |

| K-nearest neighbors | No. of neighbors | [1, 50], integer |

| Weights | [uniform, distance] | |

| Metric | [Euclidean, Manhattan, Minkowski] | |

| Support vector machine | Kernel | [linear, rbf, poly, sigmoid] |

| C | [0.1, 50], float | |

| Gamma | [0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, scale, auto] | |

| Degree | [2, 3, 4, 5], if kernel = poly | |

| Random forest | No. of estimators | [1, 500], integer |

| Max features | [auto, sqrt] | |

| Max depth | [10, 110], integer, step = 10 | |

| Min samples split | [2, 10], integer, step = 2 | |

| Min samples leaf | [1, 4], integer | |

| Light gradient-boosting machine | Objective | Multiclass |

| Boosting type | GBDT | |

| No. of leaves | [2, 256], integer | |

| Learning rate | [1 × 10−4, 0.1], uniform distribution in the log domain | |

| No. of estimators | [10, 1000], integer | |

| Reg alpha | [1 × 10−8, 10], uniform distribution in the log domain | |

| Reg lambda | [1 × 10−8, 10], uniform distribution in the log domain | |

| Subsample | [0.5, 1], float, step = 0.01 | |

| Colsample bytree | [0.5, 1], float, step = 0.01 | |

| Min child samples | [5, 50], integer, step = 5 | |

| Min child weight | [1 × 10−3, 10], float, step = 1 × 10−3 | |

| Metric | Multi logloss | |

| Num of classes | 4 | |

| Max depth | −1 | |

| Subsample freq | 1 | |

| Early stopping rounds | 20 | |

| XGBoost | Objective | Multi:softmax |

| Booster | gbtree | |

| No. of leaves | [2, 256], integer | |

| Learning rate | [1 × 10−4, 0.1], uniform distribution in the log domain | |

| No. of estimators | [10, 1000], integer | |

| Alpha | [1 × 10−8, 10], uniform distribution in the log domain | |

| Lambda | [1 × 10−8, 10], uniform distribution in the log domain | |

| Subsample | [0.5, 1], float, step = 0.01 | |

| Colsample bytree | [0.5, 1], float, step = 0.01 | |

| Min child samples | [5, 50], integer, step = 5 | |

| Min child weight | [1 × 10−3, 10], float, step = 1 × 10−3 | |

| Metric | Multi logloss | |

| Num of classes | 4 | |

| Subsample freq | 1 | |

| Early stopping rounds | 20 |

Appendix C

| Model | Single Trial Time (s) | Total CV Tuning Time (s) | Inference Time per Sample (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 1.2879 ± 0.0643 | 64.39 ± 3.22 | 0.0155 ± 0.0015 |

| KNN | 0.3867 ± 0.0455 | 19.34 ± 2.28 | 0.0376 ± 0.0109 |

| SVM | 0.3224 ± 0.0398 | 16.11 ± 1.99 | 0.0237 ± 0.0058 |

| RF | 21.0088 ± 6.9670 | 1050.44 ± 348.35 | 0.0427 ± 0.0101 |

| LGBM | 1.0313 ± 0.1558 | 51.56 ± 7.79 | 0.0924 ± 0.0081 |

| XGBM | 8.4305 ± 2.9326 | 421.52 ± 146.63 | 0.0215 ± 0.0052 |

| Model | Single Trial Time (s) | Total CV Tuning Time (s) | Inference Time per Sample (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 0.1013 ± 0.0100 | 5.06 ± 0.50 | 0.0020 ± 0.0021 |

| KNN | 0.0570 ± 0.0153 | 2.85 ± 0.76 | 0.0030 ± 0.0032 |

| SVM | 0.0598 ± 0.0158 | 2.99 ± 0.79 | 0.0032 ± 0.0059 |

| RF | 1.8527 ± 0.3578 | 92.64 ± 17.89 | 0.0176 ± 0.0102 |

| LGBM | 0.2271 ± 0.0214 | 11.36 ± 1.07 | 0.0074 ± 0.0049 |

| XGBM | 1.2151 ± 0.3844 | 60.75 ± 19.22 | 0.0019 ± 0.0022 |

| Model | Single Trial Time (s) | Total CV Tuning Time (s) | Inference Time per Sample (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 0.0747 ± 0.0146 | 3.73 ± 0.73 | 0.0018 ± 0.0028 |

| KNN | 0.0592 ± 0.0215 | 2.96 ± 1.07 | 0.0018 ± 0.0023 |

| SVM | 0.0570 ± 0.0183 | 2.85 ± 0.91 | 0.0011 ± 0.0008 |

| RF | 2.2010 ± 0.2254 | 110.05 ± 11.27 | 0.0301 ± 0.0140 |

| LGBM | 0.2268 ± 0.0153 | 11.34 ± 0.76 | 0.0071 ± 0.0108 |

| XGBM | 1.0016 ± 0.3155 | 50.58 ±15.77 | 0.0034 ± 0.0031 |

References

- Semenov, M.A.; Stratonovitch, P.; Alghabari, F.; Gooding, M.J. Adapting wheat in Europe for climate change. J. Cereal Sci. 2014, 59, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Tao, Y.; Liu, M.; Yang, D.; Zhu, M.; Ding, J.; Zhu, X.; Guo, W.; Zhou, G.; Li, C. Does temporary heat stress or low temperature stress similarly affect yield, starch, and protein of winter wheat grain during grain filling? J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 103, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzrafi, M. Climate change exacerbates pest damage through reduced pesticide efficacy. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatchett, J.H.; Starks, K.J.; Webster, J.A. Insect and mite pests of wheat. In Wheat and Wheat Improvement, 2nd ed.; Heyne, E.G., Ed.; Agronomy Monograph 13; ASA, CSSA, SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1987; pp. 625–675. [Google Scholar]

- Lukács, H.; Jócsák, I.; Somfalvi-Tóth, K.; Keszthelyi, S. Physiological responses manifested by some conventional stress parameters and biophoton emission in winter wheat as a consequence of cereal leaf beetle infestation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 839855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, M.; Jan, F.; Mantoo, M.A.; Kaur, S.; Rustgi, S.; Wani, F.J.; Sofi, P.A.; Najeeb, S.; Sharma, M.; Sofi, N.R. Antioxidant and secondary metabolite responses in wheat under cereal leaf beetle (Oulema melanopus L.) infestation. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M.; Gerling, D.; Maddox, J.V. Enhancement of biological control in annual agricultural environments. In Handbook of Biological Control; Bellows, T., Fisher, T., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 789–818. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.M.; Sarazin, M.J.; Lyons, D.B. Canadian Beetles (Coleoptera) Injurious to Crops, Ornamentals, Stored Products, and Buildings; Agriculture Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Steinger, T.; Klötzli, F.; Ramseier, H. Experimental assessment of the economic injury level of the cereal leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in winter wheat. J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistič, L.; Vučajnk, F.; Vidrih, M.; Horvat, A.; Košir, I.J.; Šilc, U.; Bohinc, T.; Trdan, S. Evaluating locally sourced inert dusts as insecticides against the cereal leaf beetle (Oulema melanopus [L.]; Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): A combined laboratory and field study. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2415393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, D.L.; Gage, S.H. The cereal leaf beetle in North America. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1981, 26, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfert, O.; Weiss, R.M.; Woods, S.; Philip, H.; Dosdall, L. Potential distribution and relative abundance of an invasive cereal crop pest, Oulema melanopus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), in Canada. Can. Entomol. 2004, 136, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, C.R.; Herbert, D.A.; Kuhar, T.P.; Reisig, D.D.; Thomason, W.E.; Malone, S. Fifty years of cereal leaf beetle in the US: An update on its biology, management, and current research. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2011, 2, C1–C5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajos, K.; Császár, O.; Sárospataki, M.; Samu, F.; Tóth, F. Linear woody landscape elements may help to mitigate leaf surface loss caused by the cereal leaf beetle. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2225–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijver, E.; Landschoot, S.; Roie, M.; Temmerman, F.; Dillen, J.; Ceuleners, K.; Wauters, A.; Haesaert, G. Inter- and intrafield distribution of cereal leaf beetle species (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Belgian winter wheat. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntin, G.D.; Flanders, K.L.; Slaughter, R.W.; Delamar, Z.D. Damage loss assessment and control of the cereal leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in winter wheat. J. Econ. Entomol. 2004, 97, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirch, G. Auftreten und Bekämpfung Phytophager Insekten an Getreide und Raps in Schleswig-Holstein; Institut für Phytopathologie und Angewandte Zoologie, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen: Gießen, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wenda-Piesik, A.; Kazek, M.; Piesik, D. Cereal leaf beetles (Oulema spp., Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) control following various dates of wheat sowing and insecticidal treatments. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2018, 64, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, L.; Mergenthaler, M.; Wutke, M.; Haberlah-Korr, V. Use of insect pest thresholds in oilseed rape and cereals: Is it worth it? Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.A.; Smith, D.H.; Lee, C. Reduction in yield of spring wheat caused by cereal leaf beetles. J. Econ. Entomol. 1972, 65, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrig, R.A.; Herbert, D.A.; Van Duyn, J.W.; Bradley, J.R. Relationship between cereal leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) egg and fourth-instar populations and impact of fourth-instar defoliation of winter wheat yields in North Carolina and Virginia. J. Econ. Entomol. 2001, 94, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, D.A.; Van Duyn, J.W. Cereal Leaf Beetle: Biology and Management; Virginia Cooperative Extension Publication: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glogoza, P. North Dakota Small Grain Insects: Cereal Leaf Beetle; North Dakota State University Extension: Fargo, ND, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tanasković, S.; Madić, M.; Đurović, D.; Knežević, D.; Vukajlović, F. Susceptibility of cereal leaf beetle (Oulema melanopa L.) in winter wheat to various foliar insecticides in western Serbia region. Rom. Agric. Res. 2012, 29, 361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Reisig, D.D.; Bacheler, J.S.; Herbert, D.A.; Kuhar, T.P.; Malone, S.; Philips, C.R.; Weisz, R. Efficacy and value of prophylactic vs. integrated pest management approaches for management of cereal leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in wheat and ramifications for adoption by growers. J. Econ. Entomol. 2012, 105, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, W. Biologie und Schadwirkung der Getreidehähnchen Lema (Oulema spp.) in der industriemäßigen Getreideproduktion. Nachrbl. Pflanzensch. DDR 1977, 31, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gallun, R.L.; Everly, R.T.; Yamazaki, W.T. Yield and milling quality of Monon wheat damaged by feeding of cereal leaf beetle. J. Econ. Entomol. 1967, 60, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, F.; Szita, É.; Simon, J.; Cséplő, M.; Botos, E.; Pertics, B.; Růžičková, J.; Gerstenbrand, R.; Rakszegi, M.; Elek, Z.; et al. Cereal leaf beetle (Oulema spp.) damage reduces yield and is more severe when natural enemy action is prevented. Crop Prot. 2024, 185, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeberli, A.; Robson, A.; Phinn, S.; Lamb, D.W.; Johansen, K. A comparison of analytical approaches for the spectral discrimination and characterization of mite infestations on banana plants. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Guo, Q. Integrated agricultural pest management through remote sensing and spatial analyses. In General Concepts in Integrated Pest and Disease Management; Oliver, M.B., Raney, A.A., Bryant, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Iost Filho, F.H.; Heldens, W.B.; Kong, Z.; Lange, E.S. Drones: Innovative technology for use in precision pest management. J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.P.M.; Gomes, F.D.G.; Pinheiro, M.M.F.; Furuya, D.E.G.; Gonçalvez, W.N.; Junior, J.M.; Osco, L.P. Detecting the attack of the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in cotton plants with machine learning and spectral measurements. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G.; Vaughan, R.A. Remote Sensing of Vegetation: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mulla, D.J. Twenty-five years of remote sensing in precision agriculture: Key advances and remaining knowledge gaps. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Huang, Y.; Loraamm, R.W.; Nie, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Spectral analysis of winter wheat leaves for detection and differentiation of diseases and insects. Field Crops Res. 2014, 156, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.; Powell, S.; Peterson, R.; Rosalen, D.; Fernandes, O. Detection of defoliation injury in peanut with hyperspectral proximal remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirik, M.; Ansley, R.J.; Michels, G.J.; Elliott, N.C. Spectral vegetation indices selected for quantifying Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia) feeding damage in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Precis. Agric. 2012, 13, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Rao, M.N.; Elliott, N.C.; Kindler, S.D.; Popham, T.W. Differentiating stress induced by greenbugs and Russian wheat aphids in wheat using remote sensing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 67, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Ma, R. Detecting aphid density of winter wheat leaf using hyperspectral measurements. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Novak, H.; Zovko, M.; Pajač Živković, I.; Lešić, V.; Maričević, M.; Lemić, D. Hyperspectral Canopy Reflectance and Machine Learning for Threshold-Based Classification of Aphid-Infested Winter Wheat. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lamb, D.W.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, J. Identification of yellow rust in wheat using in-situ spectral reflectance measurements and airborne hyperspectral imaging. Precis. Agric. 2007, 8, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashourloo, D.; Mobasheri, M.R.; Huete, A. Developing two spectral disease indices for detection of wheat leaf rust (Puccinia triticina). Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4723–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Anderegg, J.; Mikaberidze, A.; Karisto, P.; Mascher, F.; McDonald, B.A.; Walter, A.; Hund, A. Hyperspectral canopy sensing of wheat septoria tritici blotch disease. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremneva, O.Y.; Danilov, R.Y.; Sereda, I.I.; Tutubalina, O.V.; Pachkin, A.A.; Zimin, M.V. Spectral characteristics of winter wheat varieties depending on the development degree of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 830–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yao, X.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, W. Analysis of common canopy vegetation indices for indicating leaf nitrogen accumulations in wheat and rice. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2008, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Yu, Z.; Li, F.; Gnyp, M.; Koppe, W.; Bareth, G.; Zhang, F. Nitrogen status estimation of winter wheat by using an IKONOS satellite image in the North China Plain. In Computer and Computing Technologies in Agriculture V; Li, D., Chen, Y., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Ren, H.; Cao, Z.; Tian, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, T.; Tian, Y.; Han, J. Detecting leaf nitrogen content in wheat with canopy hyperspectrum under different soil backgrounds. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 32, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, B. Evaluation of hyperspectral indices for retrieval of canopy equivalent water thickness and gravimetric water content. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 3384–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Feng, M.; Xiao, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Muhammad, S.K.; Li, D. Assessment of plant water status in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) based on canopy spectral indices. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Guo, B.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Fang, Q.; Wang, J. Optimized spectral index models for accurately retrieving soil moisture (SM) of winter wheat under water stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 261, 107333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, D.; Liang, H.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Su, C.; Wei, W. Advances in Deep Learning Applications for Plant Disease and Pest Detection: A Review. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Lešić, V.; Pajač Živković, I.; Lemić, D. Detection and evaluation of environmental stress in winter wheat using remote and proximal sensing methods and vegetation indices—A review. Diversity 2023, 15, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becht, E.; McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Dutertre, C.-A.; Kwok, I.W.H.; Ng, L.G.; Ginhoux, F.; Newell, E.W. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, M.; Ullah, K.Z.; Javed, K.; Sattar, A.M.; Aamir, A.; Nida, J.; Ziqi, H.; Fuzhong, L. A comprehensive review of crop stress detection: Destructive, non-destructive, and ML-based approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1638675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Tang, K.; Yu, H.; Yan, R.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, L. Comparative analysis of feature importance algorithms for grassland aboveground biomass and nutrient prediction using hyperspectral data. Agriculture 2024, 14, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potůčková, M.; Červená, L.; Kupková, L.; Lhotáková, Z.; Lukeš, P.; Hanuš, J.; Novotný, J.; Albrechtová, J. Comparison of reflectance measurements acquired with a contact probe and an integration sphere: Implications for the spectral properties of vegetation at a leaf level. Sensors 2016, 16, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Novak, H.; Pajač Živković, I.; Zovko, M.; Lešić, V.; Maričević, M.; Lemić, D. Hyperspectral Reflectance Dataset (350–2500 nm) of Wheat Flag Leaves Under Four Levels of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage [Data set]. Zenodo. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/17507507 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Glenn, E.P.; Huete, A.R.; Nagler, P.L.; Nelson, S.G. Relationship between remotely sensed vegetation indices, canopy attributes, and plant physiological processes: What vegetation indices can and cannot tell us about the landscape. Sensors 2008, 8, 2136–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorani, F.; Rascher, U.; Jahnke, S.; Schurr, U. Imaging plants dynamics in heterogeneous environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnieli, A.; Bayarjargal, Y.; Bayasgalan, M.; Mandakh, B.; Dugarjav, C.; Burgheimer, J.; Khudulmur, S.; Bazha, S.N.; Gunin, P.D. Do vegetation indices provide a reliable indication of vegetation degradation? A case study in the Mongolian pastures. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 6243–6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Remote sensing of chlorophyll concentration in higher plant leaves. Adv. Space Res. 1998, 22, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.G.; Scharf, P.C.; Sudduth, K.A. Sun position and cloud effects on reflectance and vegetation indices of corn. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarchi, L.; Kania, A.; Ciężkowski, W.; Piórkowski, H.; Oświecimska-Piasko, Z.; Chormański, J. Recursive feature elimination and random forest classification of Natura 2000 grasslands in lowland river valleys of Poland based on airborne hyperspectral and LiDAR data fusion. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iozia, L.M.; Varone, L. Short range shifts in plant physiological responses to induced water stress: Experimental evidence of intraspecific trait variability differentiating neighbouring Mediterranean plant populations. Plant Stress 2024, 13, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Filella, I.; Gamon, J.A. Assessment of photosynthetic radiation-use efficiency with spectral reflectance. New Phytol. 1995, 131, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España Boquera, M.L.; Lobit, P.; Castellanos Morales, V. Leaf chlorophyll content estimation in the monarch butterfly biosphere reserve. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2010, 33, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Filella, I.; Biel, C.; Serrano, L.; Savé, R. The reflectance at the 950–970 nm region as an indicator of plant water status. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 1887–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.; Serrano, L.; Surfus, J.S. The photochemical reflectance index: An optical indicator of photosynthetic radiation-use efficiency across species, functional types, and nutrient levels. Oecologia 1997, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R., Jr.; Rock, B.N. Detection of changes in leaf water content using near- and middle-infrared reflectances. Remote Sens. Environ. 1989, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Imran, M. Evaluating the potential of red edge position (REP) of hyperspectral remote sensing data for real-time estimation of LAI and chlorophyll content of kinnow mandarin (Citrus reticulata) fruit orchards. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 267, 109326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, K.R.; Wang, R.; Gamon, J.A. Parallel seasonal patterns of photosynthesis, fluorescence, and reflectance indices in boreal trees. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NeurIPS 2017); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD 2016), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD 2019), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Datt, B. Remote Sensing of Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, Chlorophyll a+b, and Total Carotenoid Content in Eucalyptus Leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 66, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Wei, J.; Li, L.; Guo, E.; Kong, Y. Using Spectral Reflectance to Estimate the Leaf Chlorophyll Content of Maize Inoculated with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Under Water Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 646173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, P.L.; Pinter, P.J., Jr. Remote sensing for crop protection. Crop Prot. 1993, 12, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-R.; Li, X.; Yu, K.-Q.; Cheng, F.; He, Y. Hyperspectral Imaging for Determining Pigment Contents in Cucumber Leaves in Response to Angular Leaf Spot Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonobe, R.; Wang, Q. Nondestructive assessments of carotenoids content of broadleaved plant species using hyperspectral indices. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 145, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A.; Spiering, B.A. Optical properties of intact leaves for estimating chlorophyll concentration. J. Environ. Qual. 2002, 31, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Yasmin, J.; Mo, C.; Lee, H.; Kim, M.S.; Hong, S.J.; Cho, B.K. Outdoor applications of hyperspectral imaging technology for monitoring agricultural crops: A review. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 41, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Baret, F. PROSPECT: A model of leaf optical properties spectra. Remote Sens. Environ. 1990, 34, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, H.; Chen, J.M. Leaf pigment content. In Comprehensive Remote Sensing; Liang, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Slaton, M.R.; Hunt, E.R., Jr.; Smith, W.K. Estimating near-infrared leaf reflectance from leaf structural characteristics. Am. J. Bot. 2001, 88, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovko, M.; Žibrat, U.; Knapič, M.; Kovačić, M.B.; Romić, D. Hyperspectral remote sensing of grapevine drought stress. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.R.; Ying, Y.B.; Fu, X.P.; Zhu, S.P. Near-infrared spectroscopy in detecting leaf miner damage on tomato leaf. Biosyst. Eng. 2007, 96, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.J.; Tong, Q.X.; Pu, R.L.; Guo, X.; Zhao, C. Spectroscopic determination of wheat water status using 1650–1850 nm spectral absorption features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2001, 22, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R., Jr.; Yilmaz, M.T. Remote sensing of vegetation water content using shortwave infrared reflectances. In Remote Sensing and Modeling of Ecosystems for Sustainability IV; Gao, W., Ustin, S.L., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007; Volume 6679, p. 667902. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, E.R., Jr.; Ustin, S.L.; Riaño, D. Remote sensing of leaf, canopy, and vegetation water contents for satellite environmental data records. In Satellite-Based Applications on Climate Change; Qu, J.J., Powell, A.M., Sivakumar, M.V.K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Behmann, J.; Steinrücken, J.; Plümer, L. Detection of early plant stress responses in hyperspectral images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 93, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junttila, S.; Hölttä, T.; Saarinen, N.; Kankare, V.; Yrttimaa, T.; Hyyppä, J.; Vastaranta, M. Close-range hyperspectral spectroscopy reveals leaf water content dynamics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 277, 113071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M. Inducing drought tolerance in plants: Recent advances. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zúñiga Espinoza, C.; Khot, L.R.; Sankaran, S.; Jacoby, P.W. High-resolution multispectral and thermal remote sensing-based water stress assessment in subsurface irrigated grapevines. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, M.; Grosch, R.; Graefe, J. The use of features from fluorescence, thermography, and NDVI imaging to detect biotic stress in lettuce. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Rudd, J.C.; Xue, Q.; Bhandari, M.; Reddy, S.K.; Jessup, K.E.; Liu, S.; Devkota, R.N.; Baker, J.; Baker, S. Use of NDVI for characterizing winter wheat response to water stress in a semi-arid environment. J. Crop Improv. 2019, 33, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipatsitee, P.; Tisarum, R.; Taota, K.; Samphumphuang, T.; Eiumnoh, A.; Singh, H.P.; Cha-Um, S. Effectiveness of vegetation indices and UAV-multispectral imageries in assessing the response of hybrid maize (Zea mays L.) to water deficit stress under field environment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafri, H.Z.; Hamdan, N. Hyperspectral imagery for mapping disease infection in oil palm plantation using vegetation indices and red edge techniques. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2009, 6, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Huang, W.; Luo, J.; Huang, L.; Zhou, X. Detection and discrimination of pests and diseases in winter wheat based on spectral indices and kernel discriminant analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, P.; Rajendran, S.; Mahendran, R.K.; Naseer, S.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J.G. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) in precision agriculture: Applications and challenges. Energies 2021, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Császár, O.; Tóth, F.; Lajos, K. Estimation of the expected maximal defoliation and yield loss caused by cereal leaf beetle (Oulema melanopus L.) larvae in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Crop Prot. 2021, 145, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay-Jones, F.P. Spatial distribution of the cereal leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in wheat. Environ. Entomol. 2010, 39, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin, A.R.A.; Neves, D.C.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; da Silva Júnior, C.A.; da Silva, S.P.; Teodoro, P.E.; Baio, F.H.R. Reduction of pesticide application via real-time precision spraying. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Huang, W.; Ye, H.; Ruan, C.; Xing, N.; Geng, Y.; Peng, D. Partial least square discriminant analysis based on normalized two-stage vegetation indices for mapping damage from rice diseases using PlanetScope datasets. Sensors 2018, 18, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, D.K.; Pradhan, S.; Sehgal, V.K.; Sahoo, R.N.; Gupta, V.K.; Singh, R. Spectral Reflectance Characteristics of Healthy and Yellow Mosaic Virus Infected Soybean (Glycine max L.) Leaves in a Semiarid Environment. J. Agrometeorol. 2013, 15, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Nansen, C. Hyperspectral remote sensing to detect leafminer-induced stress in bok choy and spinach according to fertilizer regime and timing. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 2208–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susič, N.; Žibrat, U.; Širca, S.; Strajnar, P.; Razinger, J.; Knapič, M.; Vončina, A.; Urek, G.; Gerič Stare, B. Discrimination between Abiotic and Biotic Drought Stress in Tomatoes Using Hyperspectral Imaging. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 273, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshou, D.; Bravo, C.; West, J.; Wahlen, S.; McCartney, A.; Ramon, H. Automatic detection of “yellow rust” in wheat using reflectance measurements and neural networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2004, 44, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, J.J.; Singh, A.; Charkowski, A.O.; Groves, R.L.; Gray, S.M.; Bethke, P.C.; Townsend, P.A. Integrating spectroscopy with potato disease management. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrisoli, M.M.; Negrisoli, R.; da Silva, F.; Lopes, L.S.; Souza Júnior, F.S.D.; Velini, E.D.; Raetano, C.G. Soybean rust detection and disease severity classification by remote sensing. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 3246–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansen, C.; Murdock, M.; Purington, R.; Marshall, S. Early infestations by arthropod pests induce unique changes in plant compositional traits and leaf reflectance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 5158–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra, J.; Araus, J.L.; Kefauver, S.C. Farming and Earth Observation: Sentinel-2 data to estimate within-field wheat grain yield. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 107, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenova, I.; Dimitrov, P. Evaluation of Sentinel-2 vegetation indices for prediction of LAI, fAPAR and fCOVER of winter wheat in Bulgaria. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 54 (Suppl. S1), 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Li, W.; Du, Q.; Zhang, B. Dimensionality reduction of hyperspectral image with graph-based discriminant analysis considering spectral similarity. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Yan, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, B. Hyperspectral Imaging Combined with Deep Learning for the Early Detection of Strawberry Leaf Gray Mold Disease. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, M.; Nalepa, J.; Moliszewska, E.; Ruszczak, B.; Smykała, K. Early Detection of Solanum Lycopersicum Diseases from Temporally-Aggregated Hyperspectral Measurements Using Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgani, F.; Bruzzone, L. Classification of hyperspectral remote sensing images with support vector machines. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Quantitative Estimation of Chlorophyll-a Using Reflectance Spectra: Experiments with Autumn Chestnut and Maple Leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1994, 22, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Rao, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, L. Plant carotenoids: Recent advances and future perspectives. Mol. Hortic. 2022, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, W.; Ye, H.; Luo, P.; Ren, Y.; Kong, W. Using Multi-Angular Hyperspectral Data to Estimate the Vertical Distribution of Leaf Chlorophyll Content in Wheat. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishzadeh, R.; Skidmore, A.; Atzberger, C.; van Wieren, S. Estimation of Vegetation LAI from Hyperspectral Reflectance Data: Effects of Soil Type and Plant Architecture. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2008, 10, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gara, T.W.; Skidmore, A.K.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Wang, T. Leaf to canopy upscaling approach affects the estimation of canopy traits. GISci. Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 554–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Gill, H.S.; Singh, M.; Kaur, K.; Koupal, D.; Talukder, S.; Bernardo, A.; St Amand, P.; Bai, G.; Sehgal, S.K. Characterization of Flag Leaf Morphology Identifies a Major Genomic Region Controlling Flag Leaf Angle in the U.S. Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Malenovský, Z.; Van der Tol, C.; Camps-Valls, G.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.-P.; Lewis, P.; North, P.; Moreno, J. Quantifying vegetation biophysical variables from imaging spectroscopy data: A review on retrieval methods. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 589–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vegetation Index | Formula | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | [63] | |

| Red Edge Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI750) | [64] | |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (GNDVI) | [65] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Index 1 (CRI1) | [66] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Index (CRI2) | [67] | |

| Structural Independent Pigment Index (SIPI) | [68] | |

| Chlorophyll Reflectance Index green (RIgreen) | [69] | |

| Water Band Index (WBI) | [70] | |

| Photochemical Reflectance Index (PRI) | [71] | |

| Moisture Stress Index (MSI) | [72] | |

| Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) | [50] | |

| Red Edge Position (REP) | [73] | |

| Chlorophyll/Carotenoid Index (CCI) | [74] |

| LR | KNN | SVM | RF | LGBM | XGBM | Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelengths | Accuracy | 88.25 ± 2.50 | 86.98 ± 4.95 | 90 ± 2.37 | 89.52 ± 3.68 | 89.05 ± 2.84 | 87.94 ± 4.92 | 88.62 ± 3.54 |

| Precision | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | |

| Recall | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | |

| F1-score | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | |

| VI | Accuracy | 87.78 ± 3.09 | 87.62 ± 2.68 | 90.63 ± 3.54 | 86.51 ± 4.18 | 85.71 ± 3.67 | 86.83 ± 3.43 | 87.51 ± 3.43 |

| Precision | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | |

| Recall | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | |

| F1-score | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | |

| UMAP | Accuracy | 84.29 ± 3.92 | 85.55 ± 4.99 | 88.41 ± 5.55 | 85.71 ± 5.55 | 82.38 ± 6.75 | 81.43 ± 3.89 | 84.63 ± 5.10 |

| Precision | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.05 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.05 | |

| Recall | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | |

| F1-score | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.05 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skendžić, S.; Novak, H.; Zovko, M.; Pajač Živković, I.; Lešić, V.; Maričević, M.; Lemić, D. Hyperspectral Sensing and Machine Learning for Early Detection of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage in Wheat: Insights for Precision Pest Management. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232482

Skendžić S, Novak H, Zovko M, Pajač Živković I, Lešić V, Maričević M, Lemić D. Hyperspectral Sensing and Machine Learning for Early Detection of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage in Wheat: Insights for Precision Pest Management. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232482

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkendžić, Sandra, Hrvoje Novak, Monika Zovko, Ivana Pajač Živković, Vinko Lešić, Marko Maričević, and Darija Lemić. 2025. "Hyperspectral Sensing and Machine Learning for Early Detection of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage in Wheat: Insights for Precision Pest Management" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232482

APA StyleSkendžić, S., Novak, H., Zovko, M., Pajač Živković, I., Lešić, V., Maričević, M., & Lemić, D. (2025). Hyperspectral Sensing and Machine Learning for Early Detection of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage in Wheat: Insights for Precision Pest Management. Agriculture, 15(23), 2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232482