A Path Analysis of Behavioral Drivers of Household Food Waste in Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

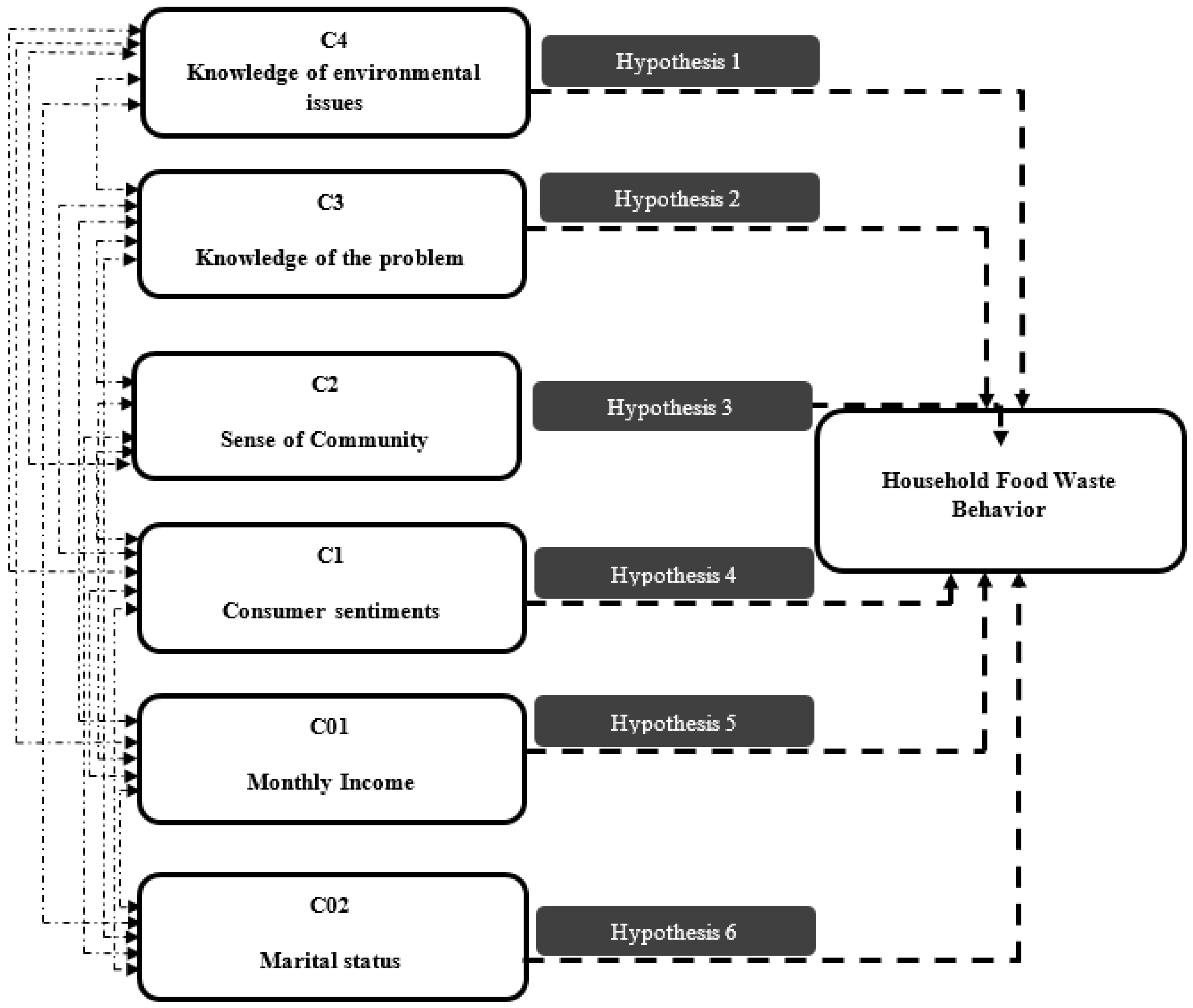

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

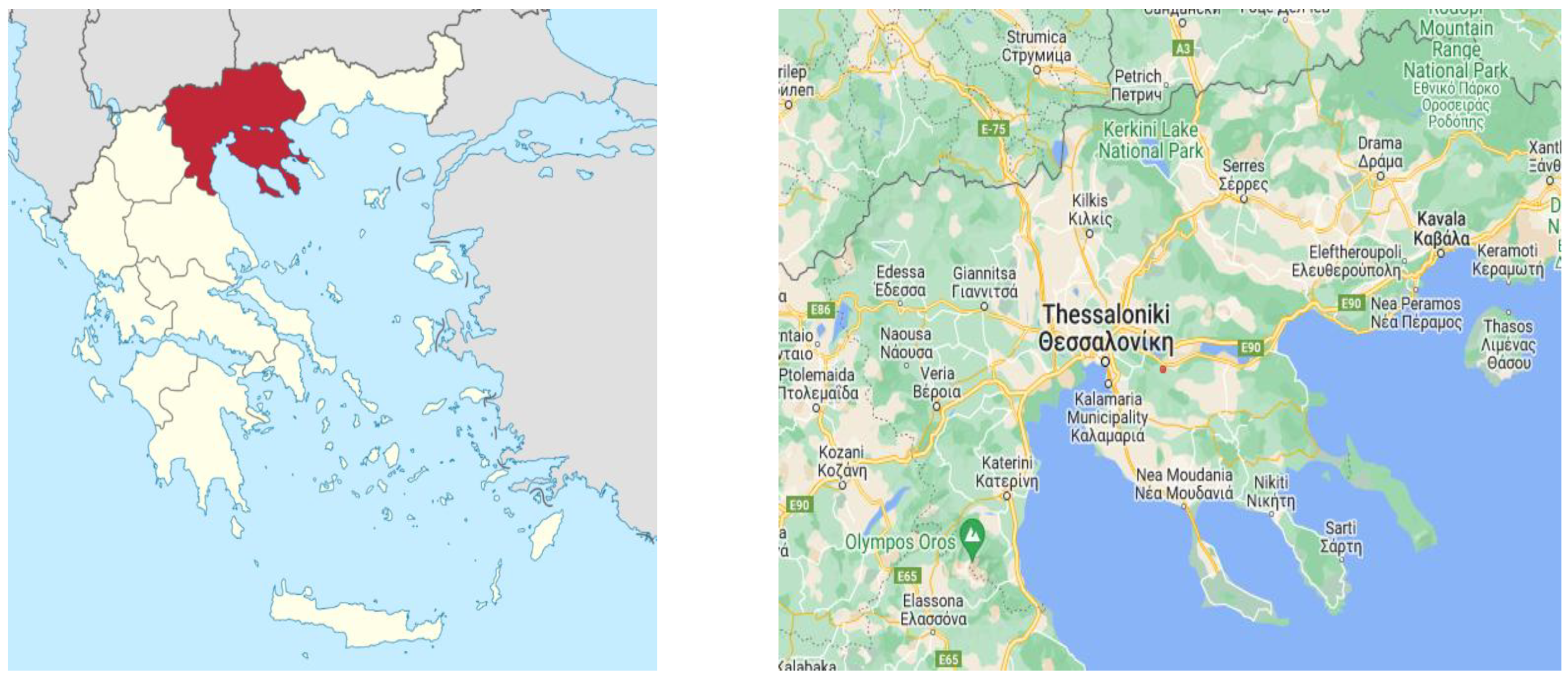

3.1. Sampling Procedure

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.3. Methodology

Survey Construction and Validation

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EU Commission. Roadmap to a Resource-Efficient Europe; COM/2011/0571; EU Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint Full Cost Accounting; Food Wastage Footprint; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; von Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Teigiserova, D.A.; Hamelin, L.; Thomsen, M. Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 136033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Mattia, G.; Di Leo, A.; Pratesi, C.A. The household wasteful behaviour framework: A systematic review of consumer food waste. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Rios, C.; Hofmann, A.; Mackenzie, N. Sustainability oriented innovations in food waste management technology. Sustainability 2020, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chaudhary, A.; Mathys, A. Nutritional and environmental losses embedded in global food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelakis, C.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Keramopoulou, C.; Theodossiou, G. Green Growth, Green Development and Climate Change Perceptions: Evidence from a Greek Region. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklavos, G.; Theodossiou, G.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Karelakis, C.; Ragazou, K. Environmental, Social, and Governance Based Artificial Intelligence Governance: Digitalizing Firms’ Leadership and Human Resources Management. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noleppa, S.; Cartsburg, M. Das Grosse Wegschmeissen: Vom Acker bis zum Verbraucher: Ausmaß und Umwelteffekte der Lebensmittelverschwendung in Deutschland; WWF Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K. Explaining and promoting household food waste prevention by an environmental psychological based intervention study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 111, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Çakir, M.; Peterson, H.H.; Novak, L.; Rudi, J. On the measurement of food waste. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, U.; Loy, J.P.; Ren, Y. Measurement and reduction of food loss and waste: Reconsidered. Agric. Econ. 2018, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champions 12.3. Guidance on Interpreting Sustainable Development Goal Target 12.3. [Internet Document]. Available online: https://champions123.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/champions-12-3-guidance-on-interpreting-sdg-target-12-3.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- FAO. FAO STAT; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: http://faostat.fao.org (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Principato, L.; Ruini, L.; Guidi, M.; Secondi, L. Adopting the circular economy approach on food loss and waste: The case of Italian pasta production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklavos, G.; Theodossiou, G.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Karelakis, C.; Lazarides, T. Reinforcing sustainability and efficiency for agrifood firms: A theoretical framework. In Sustainability Through Green HRM and Performance Integration; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, L.; Bruggemann, R. The 17 United Nations’ sustainable development goals: A status by 2020. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo Stangherlin, I.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Basso, K. The impact of social norms on suboptimal food consumption: A solution for food waste. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2020, 32, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsangas, M.; Gavriel, I.; Doula, M.; Xeni, F.; Zorpas, A.A. Life cycle analysis in the framework of agricultural strategic development planning in the Balkan region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardra, S.; Barua, M.K. Halving food waste generation by 2030: The challenges and strategies of monitoring UN sustainable development goal target 12.3. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, M.; Cui, H.D. Using food loss reduction to reach food security and environmental objectives—A search for promising leverage points. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Alboni, F.; Falasconi, L. Quantities, determinants, and awareness of households’ food waste in Italy: A comparison between diary and questionnaires quantities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverenz, D.; Moussawel, S.; Maurer, C.; Hafner, G.; Schneider, F.; Schmidt, T.; Kranert, M. Quantifying the prevention potential of avoidable food waste in households using a self reporting approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Barone, A.M. Domestic food practices: A study of food management behaviors and the role of food preparation planning in reducing waste. Appetite 2018, 121, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Holsteijn, F.; Kemna, R. Minimizing food waste by improving storage conditions in household refrigeration. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakos, D.; Szabó Bódi, B.; Kasza, G. Consumer awareness campaign to reduce household food waste based on structural equation behavior modeling in Hungary. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24580–24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Massow, M.; Parizeau, K.; Gallant, M.; Wickson, M.; Haines, J.; Ma, D.W.; Wallace, A.; Carroll, N.; Duncan, A.M. Valuing the multiple impacts of household food waste. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Pratesi, C.A. Reducing food waste: An investigation on the behaviour of Italian youths. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangherlin, I.D.C.; De Barcellos, M.D. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, J.A.; Alaybek, B.; Hartman, R.; Mika, G.; Leib, E.M.B.; Plekenpol, R.; Branting, K.; Rao, D.; Leets, L.; Sprenger, A. Initial assessment of the efficacy of food recovery policies in US States for increasing food donations and reducing waste. Waste Manag. 2024, 176, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, S. The effect of consumer perception on food waste behavior of urban households in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Rather, M.I.; Zargar, U.R. Understanding the food waste behavior in university students: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.; Zacharatos, T.; Boukouvala, V. Consumer behaviour and household food waste in Greece. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 965–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.; Choedron, K.T.; Ajai, O.; Duke, O.; Jijingi, H.E. Systematic review of factors influencing household food waste behaviour: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 43, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bremer, P.; Jowett, T.; Lee, M.; Parker, K.S.; Gaugler, E.C.; Mirosa, M. What influences consumer food waste behaviour when ordering food online? An application of the extended theory of planned behaviour. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2330728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Segrè, A.; Setti, M.; Vittuari, M. Such a shame! A study on self perception of household food waste. Sustainability 2019, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikovskaja, V.; Aschemann Witzel, J. Food waste avoidance actions in food retailing: The case of Denmark. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2017, 29, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Nilashi, M.; Tseng, M.L.; Senali, M.G.; Abbasi, G.A. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour: A systematic review. Appetite 2022, 176, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo, G.; Cerroni, S.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Yang, W. Impact of COVID-19 on household food waste: The case of Italy. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 585090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, E.A.D.M.; Freitas, M.G.M.T.D.; Demo, G. Food waste in restaurants: Evidence from Brazil and the United States. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 35, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Javadi, F.; Hiramatsu, M. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behavior in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baya Chatti, C.; Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H. Closing the Loop: Exploring Food Waste Management in the Near East and North Africa (NENA) Region during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, D. How to reduce household food waste during and after the COVID-19 lockdown? Evidence from a structural model. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2024, 68, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, Z.F.; Sobhani, S.M.J.; Barbosa, M.W.; Amiri Ardekani, E.; Dehghani, S.; Sasani, N.; De Steur, H. Determinants of household food waste behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: An integrated model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 26205–26235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashar, A.; Nyagadza, B.; Ligaraba, N.; Maziriri, E.T. The influence of COVID-19 on consumer behaviour: A bibliometric review analysis and text mining. Arab Gulf J. Sci. Res. 2024, 42, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatab, A.A.; Tirkaso, W.T.; Tadesse, E.; Lagerkvist, C.J. An extended integrative model of behavioural prediction for examining households’ food waste behaviour in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Agovino, M.; Ferraro, A.; Mariani, A. Household food waste: A case study in Southern Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Roe, B.E. Segmenting US consumers by food waste attitudes and behaviors: Opportunities for targeting reduction interventions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 45, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, L.; Fiszman, S.; Puerta, P.; Chaya, C.; Tárrega, A. The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karelakis, C.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Theodosiou, G.; Goulas, A. Local Products Dynamics and the Determinants of Purchasing Behaviour. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2021, 16, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.E.; Bender, K.; Qi, D. The impact of COVID-19 on consumer food waste. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Voronova, V.; Kloga, M.; Paço, A.; Minhas, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Sivapalan, S. COVID-19 and waste production in households: A trend analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 145997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cequea, M.M.; Vásquez Neyra, J.M.; Schmitt, V.G.H.; Ferasso, M. Household food consumption and wastage during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: A comparison between Peru and Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Prabhakar, G.; Duong, L.N. Usage of online food delivery in food waste generation in China during the crisis of COVID-19. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 5602–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. How household food shopping behaviors changed during the COVID-19 lockdown period: Evidence from Beijing, China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, S.T.; Lindahl, J.M.M. Forty years of the theory of planned behavior: A bibliometric analysis (1985–2024). Manag. Rev. Q. 2025, 13, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, K.C.; Gillis, H.L.; Kivlighan, D.M., Jr. Process factors explaining psychosocial outcomes in adventure therapy. Psychotherapy 2017, 54, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucha, L.; Oravecz, T. Assumptions and perceptions of food wasting behavior and intention to reduce food waste in the case of Generation Y and Generation X. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Q.; Han, G. From attitude to behavior: The effect of residents’ food waste attitudes on their food waste behaviors in Shanghai. Foods 2024, 13, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority, Good Practice Advisory Committee. First Annual Report. 2023. Available online: http://www.statistics.gr (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; Johan Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Google. (n.d.). Google Maps [Map]. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Κεντρική+Μακεδονία (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ng, W.Z.; Erdembileg, S.; Liu, J.C.; Tucker, J.D.; Tan, R.K.J. Increasing rigor in online health surveys through the use of data screening procedures. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, 68092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessner, C.; Reiß, F.; Sand, M.; Knirsch, F.; Behn, S.; Hanssen-Doose, A.; Kaman, A.; Reichert, M.; Olfermann, R.; Wagner, P.; et al. Strategies to minimize selection bias in digital population-based studies in sport and health sciences: Methodological and empirical insights from the COMO study. Dtsch. Z. Für Sportmed. 2025, 76, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryer, T.; Zavatarro, S. Social media and public administration: Theoretical dimensions and introduction to symposium. Adm. Theory Prax. 2011, 33, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, M.; Matz, S.C.; Gosling, S.D.; Popov, V.; Stillwell, D. Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J. Testing evolutionary and ecological hypotheses using path analysis and structural equation modelling. Funct. Ecol. 1992, 6, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Chau, K.Y.; Bashir, S.; Habib, M.D.; Azam, R.I.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of household food waste reduction: A fresh insight on youth’s emotional and cognitive behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.A.; Ferrari, G.; Secondi, L.; Principato, L. From the table to waste: An exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jereme, I.A.; Siwar, C.; Begum, R.A.; Talib, B.A.; Choy, E.A. Analysis of household food waste reduction towards sustainable food waste management in Malaysia. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2018, 44, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food waste paradox: Antecedents of food disposal in low income households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boulet, M.; Hoek, A.C.; Raven, R. Towards a multi level household food waste and consumer behaviour framework: Untangling spaghetti soup. Appetite 2021, 156, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withanage, S.V.; Dias, G.M.; Habib, K. Review of household food waste quantification methods: Focus on composition analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.E.; Liu, G.; Cheng, S. Rural household food waste characteristics and driving factors in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.A.; Landry, C.E. Household food waste and inefficiencies in food production. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Bhadain, M.; Baboo, S. Household food waste: Attitudes, barriers, and motivations. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2016–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehman, J.M.; Babbitt, C.W.; Flynn, C. What predicts and prevents source separation of household food waste? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.L.; Guan, W.J.; Duan, C.Y.; Zhang, N.F.; Lei, C.L.; Hu, Y.; Chen, A.L.; Li, S.Y.; Zhuo, C.; Deng, X.L.; et al. Effect of recombinant human granulocyte colony–stimulating factor for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and lymphopenia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fami, H.S.; Aramyan, L.H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Alambaigi, A. Determinants of household food waste behavior in Tehran city: A structural model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Ruiz, R.; Costa Font, M.; Gil, J.M. Moving ahead from food related behaviours: An alternative approach to understand household food waste generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, M.; Falasconi, L.; Segrè, A.; Cusano, I.; Vittuari, M. Italian consumers’ income and food waste behavior. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Calabrò, G.; De Pascale, A.; Fazio, A.; Giannetto, C. Household food waste and eating behavior: Empirical survey. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 3059–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.C.; Olthof, M.R.; Boevé, A.J.; van Dooren, C.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Brouwer, I.A. Socio demographic predictors of food waste behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; O’Connor, P.J. Household food waste disposal behaviour is driven by perceived personal benefits, recycling habits, and ability to compost. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.; Shaw, P.J.; Richards, B.; Clegg, Z.; Smith, D. What nudge techniques work for food waste behaviour change at the consumer level? A systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.; Mataraarachchi, S. A review of landfills, waste, and the nearly forgotten nexus with climate change. Environments 2021, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, C.; Geetha, P.S.; Vijayalakshmi, R.; Mini, M.L.; Pasupathi, E. Global effects of food waste. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 690–699. [Google Scholar]

- Vijay, V.; Kinsland, A.; Shah, T. CellMore: Reducing Food Waste and Landfills While Increasing Plastic Alternatives; Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy: Aurora, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, A.N.; Kearney, J.M.; O’Sullivan, E.J. The underlying role of food guilt in adolescent food choice: A potential conceptual model for adolescent food choice negotiations under circumstances of conscious internal conflict. Appetite 2024, 192, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal e Hasan, S.M.; Mortimer, G.; Ahmadi, H.; Abid, M.; Farooque, O.; Amrollahi, A. How tourists’ negative and positive emotions motivate their intentions to reduce food waste. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2039–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Lionis, C.; Costarelli, V. Socioeconomic inequalities in relation to health and nutrition literacy in Greece. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, D.; Yap, C.C.; Wu, S.L.; Berezina, E.; Aroua, M.K.; Gew, L.T. A systematic review of country specific drivers and barriers to household food waste reduction and prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 242 | 36.23% |

| Female | 426 | 63.77% | |

| Age | 18–24 years old | 196 | 29.34% |

| 30–39 years old | 206 | 30.84% | |

| 40–59 years old | 249 | 37.28% | |

| 65+ years old | 17 | 2.54% | |

| Education level | High School | 6 | 0.90% |

| Professional Degree | 114 | 17.07% | |

| Bachelors | 230 | 34.43% | |

| Masters | 245 | 36.68% | |

| Doctorate | 73 | 10.93% | |

| Marital status | Free | 302 | 45.21% |

| Married | 329 | 49.25% | |

| Divorced | 30 | 4.49% | |

| Widow | 7 | 1.05% | |

| Occupation | In paid work | 529 | 79.19% |

| Unemployed | 51 | 7.63% | |

| College student | 88 | 13.17% | |

| Habitation type | Village (up to 10,000 inhabitants) | 130 | 19.46% |

| City (>10,000 inhabitants) | 538 | 80.54% | |

| Monthly Income | €0–500 | 122 | 18.26% |

| €501–1000 | 211 | 31.59% | |

| €1001–1500 | 169 | 25.30% | |

| €1501–2000 | 72 | 10.78% | |

| €2001 and above | 94 | 14.07% | |

| Number of household members | 1 | 122 | 18.26% |

| 2 | 141 | 21.11% | |

| 3 | 142 | 21.26% | |

| 4 | 196 | 29.34% | |

| Five and above | 67 | 10.03% | |

| Number of children in the family | 1 | 116 | 17.37% |

| 2 | 210 | 31.44% | |

| 3 | 57 | 8.53% | |

| Four and above | 18 | 2.69% | |

| None | 267 | 39.97% |

| Code | Name of Factor | Measurement Scale | Source/Reference | Construct-Items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C20 | C5 Reduce | 3-item scale, Likert 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree–5 = strongly agree) | [65] | C561 | I will pay more attention to their purchase |

| C562 | I will pay more attention to my meals | ||||

| C563 | I will become better informed about the effects of food waste | ||||

| C20 | C7 Recycle | 4-item scale, Likert 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree– 5 = strongly agree) | [73] | C769 | I participate in the recycling of household food waste |

| C770 | I recycle to reduce landfill problems | ||||

| C771 | I intend to promote the recycling of household food waste | ||||

| C772 | I resell a large portion of my leftover food for financial reasons. | ||||

| C2 | Sense of Community | 4 items, Likert 1–5 from (1 = strongly disagree–5 = strongly agree) | [73] | C248 | People from my workplace feel like we are members of the same community |

| C249 | To the people of my neighborhood, I feel that we are members of the same community | ||||

| C250 | To the people from my town, I feel like we are members of the same community | ||||

| C251 | To the people from my country, I feel that we are members of the same community | ||||

| C20 | C6 Reuse | 5-item scale, Likert 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree–5 = strongly agree) | [74] | C664 | It will significantly benefit the environment |

| C665 | To make the most of them | ||||

| C666 | To save money | ||||

| C667 | Instead of buying new ones | ||||

| C668 | Their disposal contributes significantly to landfill problems | ||||

| C4 | Knowledge of environmental issues | 5 items, Likert 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree–5 = strongly agree) | [75] | C456 | I know how to buy products that are environmentally friendly |

| C457 | I know about food waste recycling | ||||

| C458 | I know about purchasing packaging that reduces waste | ||||

| C459 | I know environmental symbols | ||||

| C460 | I know various environmental issues | ||||

| C3 | Knowledge of the problem | 4 items, Likert 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree–5 = strongly agree) | [76] | C352 | Reducing household food waste is an important way to reduce pollution |

| C353 | Reducing household food waste creates a better environment for future generations | ||||

| C354 | Reducing household food waste is a critical way to reduce the unnecessary use of landfills | ||||

| C355 | Reducing household food waste is a meaningful way to conserve natural resources | ||||

| C1 | Consumer sentiments | 4 items, Likert 1–5 from (1 = strongly disagree–5 = strongly agree) | [77] | C144 | I feel guilty when I waste food, as it has a negative impact on the environment |

| C145 | I feel guilty when I waste food, as it has a negative impact on the economy | ||||

| C146 | I feel guilty when I waste food, as it has a negative impact on society | ||||

| C147 | I feel ashamed when I waste food, as this has a negative impact on the environment. | ||||

| C01 | Monthly Income | Self-reported, categorical | Demographic variable | A11 | Gender |

| A88 | Monthly income | ||||

| C02 | Marital status | Self-reported, categorical | Demographic variable | A44 | Marital status |

| A99 | Number of household members | ||||

| A1010 | Number of children in the family |

| Factor Code | Name of Construct-Items | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance (%) | Goodness-of-Fit Measures | Standardized Path Coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 | C769 | 0.848 | 2317 | 57.918 | X2: 857,448 | df: 6 | p: 0.00 | 0.729 |

| C770 | 0.878 | 0.833 | ||||||

| C771 | 0.887 | 0.849 | ||||||

| C6 | C664 | 0.816 | 3361 | 67.229 | X2: 1,727,698 | df: 10 | p: 0.00 | 0.788 |

| C665 | 0.828 | 0.782 | ||||||

| C666 | 0.818 | 0.741 | ||||||

| C667 | 0.841 | 0.768 | ||||||

| C668 | 0.796 | 0.760 | ||||||

| C5 | C561 | 0.920 | 2488 | 82.933 | X2: 1,229,766 | df: 3 | p: 0.00 | 0.890 |

| C562 | 0.921 | 0.883 | ||||||

| C563 | 0.891 | 0.817 | ||||||

| C4 | C456 | 0.771 | 3408 | 68.153 | X2: 1,691,840 | df: 10 | p: 0.00 | 0.703 |

| C457 | 0.827 | 0.777 | ||||||

| C458 | 0.851 | 0.812 | ||||||

| C459 | 0.850 | 0.806 | ||||||

| C460 | 0.826 | 0.783 | ||||||

| C3 | C352 | 0.891 | 3109 | 77.737 | X2: 1,771,198 | df: 6 | p: 0.00 | 0.873 |

| C353 | 0.912 | 0.909 | ||||||

| C354 | 0.869 | 0.797 | ||||||

| C355 | 0.853 | 0.771 | ||||||

| C2 | C248 | 0.806 | 3035 | 75.867 | X2: 1,694,698 | df: 6 | p: 0.00 | 0.709 |

| C249 | 0.896 | 0.843 | ||||||

| C250 | 0.918 | 0.918 | ||||||

| C251 | 0.859 | 0.826 | ||||||

| C1 | C144 | 0.881 | 2973 | 74.318 | X2: 1,529,196 | df: 6 | p: 0.00 | 0.853 |

| C145 | 0.881 | 0.798 | ||||||

| C146 | 0.877 | 0.782 | ||||||

| C01 | A11 | 0.787 | 1177 | 23.532 | X2: 548,496 | df: 10 | p: 0.00 | −0.462 |

| A88 | −0.730 | 0.520 | ||||||

| C02 | A44 | 0.702 | 2045 | 40.908 | 0.547 | |||

| A99 | 0.783 | 0.544 | ||||||

| A1010 | −0.831 | −0.908 | ||||||

| Code | C4 | C3 | C2 | C1 | C01 | C02 | K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of environmental issues | C4 | 1 | ||||||

| Knowledge of the problem | C3 | 0.307 ** | 1 | |||||

| Sense of Community | C2 | 0.373 ** | 0.378 ** | 1 | ||||

| Consumer sentiments | C1 | 0.440 ** | 0.567 ** | 0.450 ** | 1 | |||

| Monthly Income | C01 | 0.158 ** | 0.019 | 0.079 * | 0.065 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | C02 | 0.024 | 0.070 | 0.023 | 0.040 | 0.045 | 1 | |

| Food Waste Behavior | K | 0.407 ** | 0.517 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.563 ** | 0.097 * | 0.126 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papanikolaou, Z.; Karelakis, C. A Path Analysis of Behavioral Drivers of Household Food Waste in Greece. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2481. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232481

Papanikolaou Z, Karelakis C. A Path Analysis of Behavioral Drivers of Household Food Waste in Greece. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2481. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232481

Chicago/Turabian StylePapanikolaou, Zacharias, and Christos Karelakis. 2025. "A Path Analysis of Behavioral Drivers of Household Food Waste in Greece" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2481. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232481

APA StylePapanikolaou, Z., & Karelakis, C. (2025). A Path Analysis of Behavioral Drivers of Household Food Waste in Greece. Agriculture, 15(23), 2481. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232481