Adoption and Perception of Precision Technologies in Agriculture: Systematic Review and Case Study in the PDO Wines of Granada, Southern Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

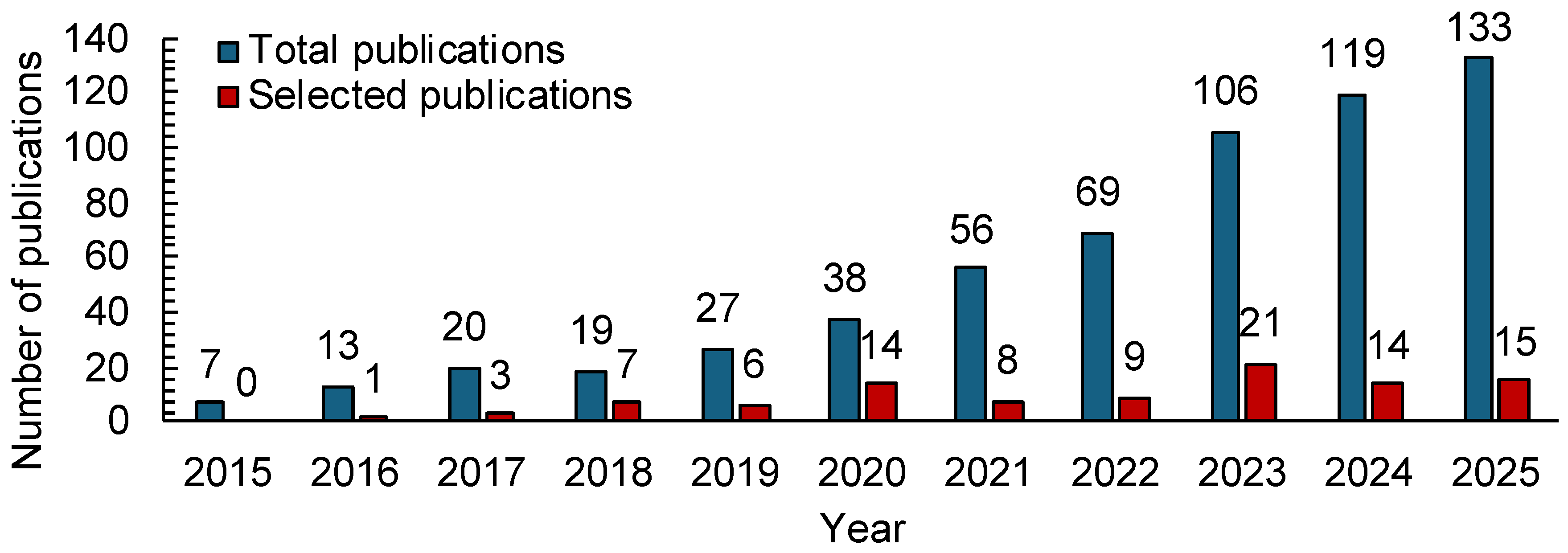

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

2.2. Case Study

2.2.1. PDO Wines of Granada

2.2.2. Environmental Characteristics of PDO Wines of Granada

2.2.3. Design, Sample, and Analyzed Variables

3. Results

3.1. Findings from the Systematic Literature Review

3.2. Assessment of Technology Adoption and Perception in the PDO Wines of Granada

3.2.1. Socio-Demographic Profiles of the Sample and Land Characterization

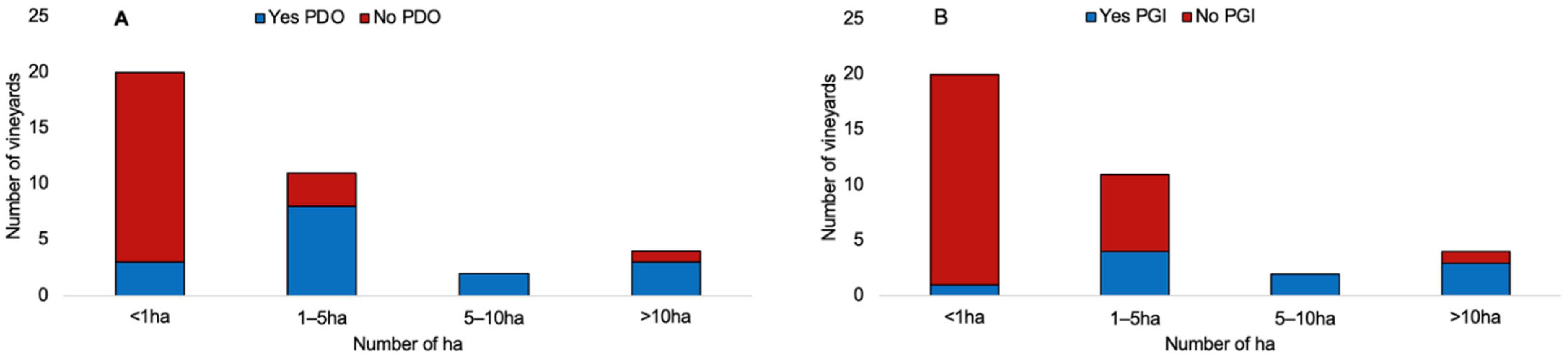

3.2.2. Interaction Between Vineyard Size and Productive Orientation

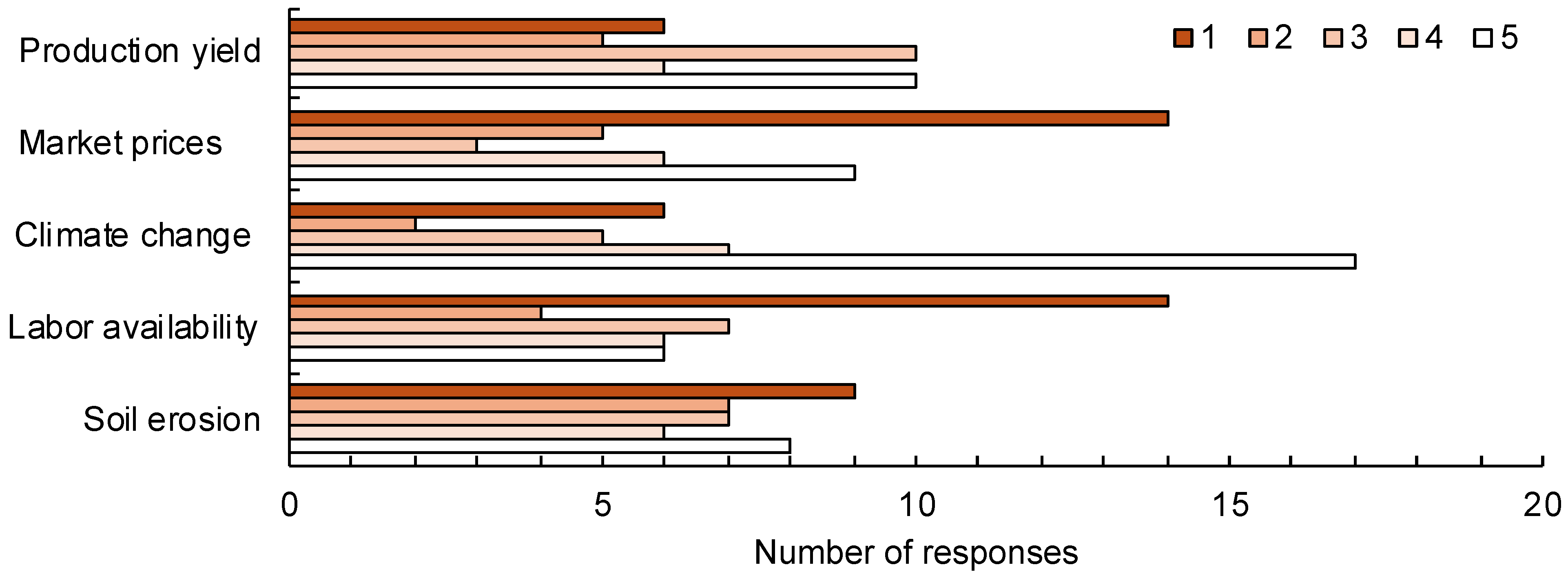

3.2.3. Perceived Risks in Vineyard Management

- Human resources: Labor availability shows polarized perceptions. A total of 14 respondents rated it as unimportant (1), while 12 rated it high (4–5), indicating contrasting views on the need for qualified personnel.

- Economic factors: Market prices also reveal polarization, with 14 respondents considering them unimportant (1), while 9 rated them as critical (5), with few intermediate responses.

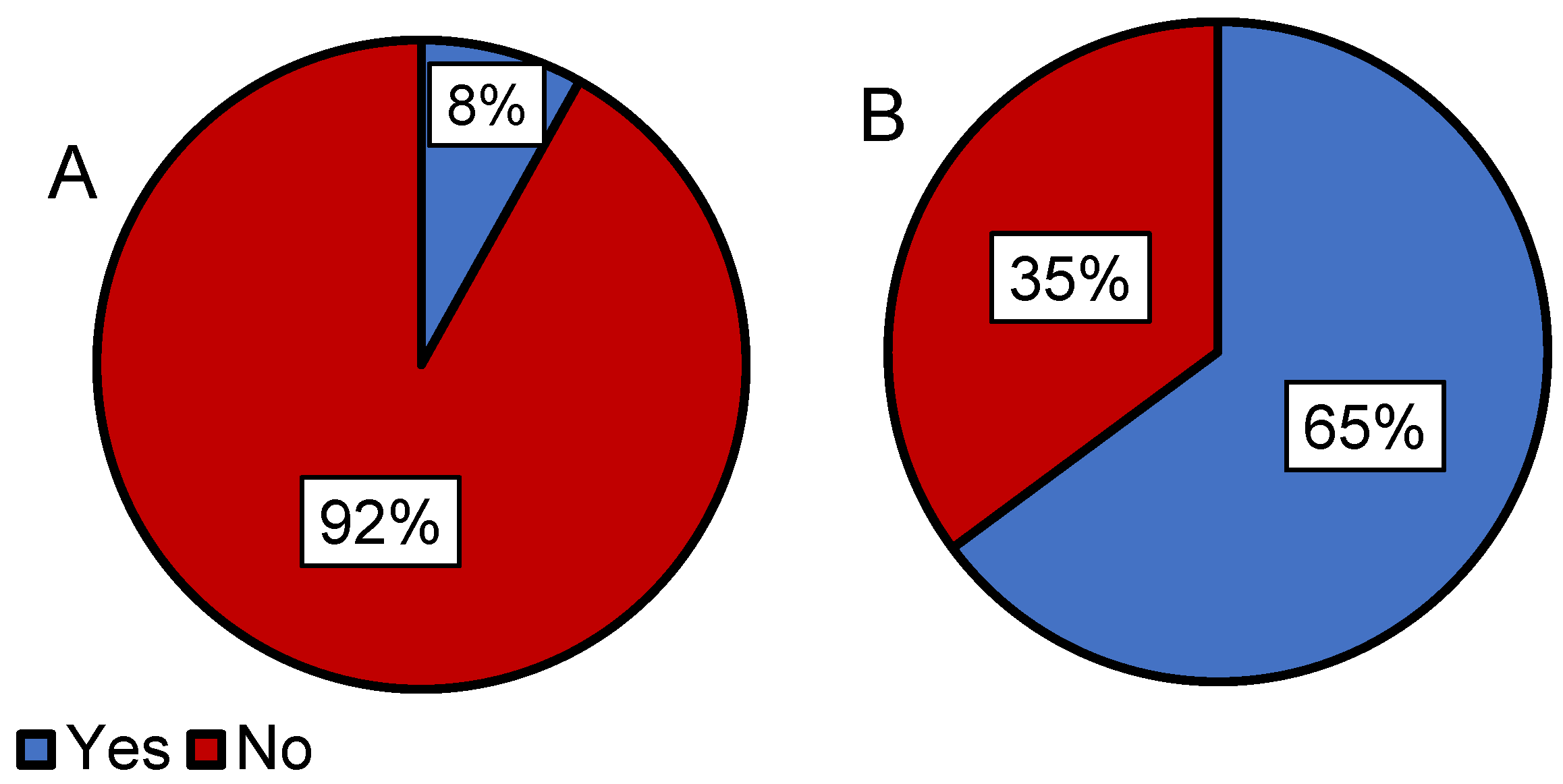

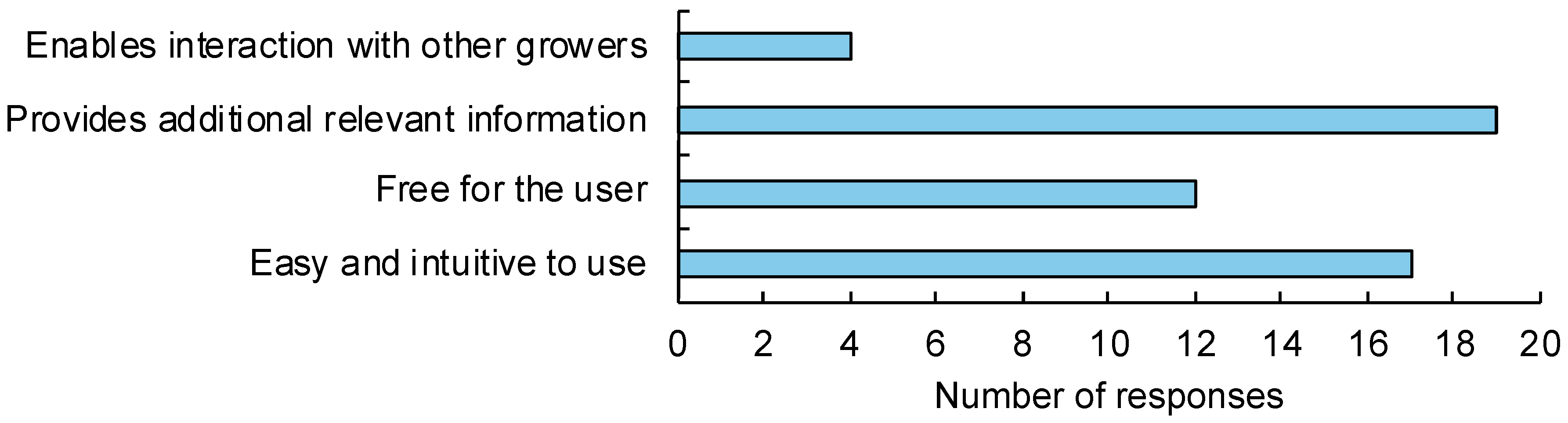

3.2.4. Technology Use and Desired Digital Tools

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cisternas, I.; Velásquez, I.; Caro, A.; Rodríguez, A. Systematic literature review of implementations of precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, I.; Phadikar, S.; Majumder, K. State-of-the-art technologies in precision agriculture: A systematic review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4878–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Qiang, Z. A review of the application of UAV multispectral remote sensing technology in precision agriculture. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Heckelei, T.; Gerullis, M.K.; Börner, J.; Rasch, S. Adoption and diffusion of digital farming technologies-integrating farm-level evidence and system interaction. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Keesstra, S.D.; Cerdà, A. Updating the scientific content of the modern geography of viticulture for human, physical and regional applied studies. Mediterr. Geosci. Rev. 2024, 6, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Abdollahi, A.; Hassoun, A. Precision agriculture: A bibliometric analysis and research agenda. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, I. Análisis y Manejo de la Variabilidad Intraparcelaria Del Viñedo en Relación Con la Calidad de la Uva y Del Vino. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Rioja, La Rioja, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tamirat, T.W.; Pedersen, S.M.; Lind, K.M. Farm and operator characteristics affecting adoption of precision agriculture in Denmark and Germany. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2018, 68, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.; Peraita Briceño, G. Innovación Tecnológica en el Sector Vitivinícola. 2006. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/108411/ortega_c.pdf?sequence=3 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Blasch, J.; van der Kroon, B.; van Beukering, P.; Munster, R.; Fabiani, S.; Nino, P.; Vanino, S. Farmer preferences for adopting precision farming technologies: A case study from Italy. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2022, 49, 33–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Di Pasquale, J.; Vecchio, Y.; Capitanio, F. Precision farming: Barriers of variable rate technology adoption in Italy. Land 2023, 12, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annosi, M.C.; Brunetta, F.; Monti, A.; Nati, F. Is the trend your friend? An analysis of technology 4.0 investment decisions in agricultural SMEs. Comput. Ind. 2019, 109, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibbern, T.; Romani, L.A.S.; Massruhá, S.M.F.S. Main drivers and barriers to the adoption of Digital Agriculture technologies. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Schouteten, J.J.; Degieter, M.; Krupanek, J.; Jarosz, W.; Areta, A.; Emmi, L.; De Steur, H.; Gellynck, X. European stakeholders’ perspectives on implementation potential of precision weed control: The case of autonomous vehicles with laser treatment. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 2200–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque-Reyes, J.R.; Zidi, A.; Peña-Acevedo, A.; Gallardo-Cobos, R. Assessing Agri-Food Digitalization: Insights from Bibliometric and Survey Analysis in Andalusia. World 2025, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foguesatto, C.R.; Borges, J.A.R.; Machado, J.A.D. A review and some reflections on farmers’ adoption of sustainable agricultural practices worldwide. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarashynskaya, A.; Prus, P. Precision Agriculture implementation factors and adoption potential: The case study of Polish agriculture. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; O’Hare, G.; Coyle, D. Understanding technology acceptance in smart agriculture: A systematic review of empirical research in crop production. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzante, S.; Labarta, R.; Bilton, A. Adoption of agricultural technology in the developing world: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, A.; Charatsari, C.; Bournaris, T.; Loizou, E.; Paltaki, A.; Lazaridou, D.; Lioutas, E.D. A first view on the competencies and training needs of farmers working with and researchers working on precision agriculture technologies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.L.H.; Khuu, D.T.; Halibas, A.; Nguyen, T.Q. Factors that influence the intention of smallholder rice farmers to adopt cleaner production practices: An empirical study of precision agriculture adoption. Eval. Rev. 2024, 48, 692–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasanta Martínez, T.; Nadal-Romero, E.; Sáenz, R. El viñedo y el vino entre 1995 y 2019: Veinticinco años de cambios en la producción, mercado y consumo de vino en el mundo. Cuad. Investig. Geogr. Geogr. Res. Lett. 2023, 49, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía Ayala, W.; Nodari, E.; Petrick, G.M.; Cerdá, J.M.; Rojas, F. Vitivinicultura en las Américas. In Perspectiva Geográfica; SPE: Richardson, TX, YSA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rosúa-Campos, J.L.; Cortés-Heredia, B. Rutas Paisajísticas por el Viñedo de la Provincia de Granada; Editorial Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2016; 208p. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Regulador DOP Vinos de Granada. (s.f.). Normativa y zonas de Producción. Available online: https://www.vinosdegranada.es (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- García-Escudero, E.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M. Evolución del Cultivo de la vid en España en los Últimos Cincuenta Años. 2022. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/306893/1/Evoluci%C3%B3n%20del%20cultivo%20de%20la%20vid%20en%20Espa%C3%B1a%20en%20los%20%C3%BAltimos%20cincuenta%20a%C3%B1os.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Rodríguez Fernández, M. Viticultura de Precisión Para la Caracterización y Gestión de Viñedos en un Contexto de Cambio Climático. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Internacionales, A.F. La Relevancia Económica y Social del Sector Vitivinícola en España, 2023. Available online: https://interprofesionaldelvino.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Informe_relevancia_economica_y_social_del_sector_vitivinicola-_en-_Espana_2023_OIVE_vf.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- MAPA. Encuesta de Superficies y Rendimientos de Cultivos (ESYRCE). 2021. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/estadistica/temas/estadisticas-agrarias/agricultura/esyrce/ (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Pomarici, E.; Corsi, A.; Mazzarino, S.; Sardone, R. The Italian wine sector: Evolution, structure, competitiveness and future challenges of an enduring leader. Ital. Econ. J. 2021, 7, 259–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couderc, J.P.; Marchini, A. Governance, commercial strategies and performances of wine cooperatives: An analysis of Italian and French wine producing regions. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, n71, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.; Sierra, C.; García Chicano, J.L. Influencia del Clima y Suelo en el Desarrollo del Olivar en la Provincia de Granada. 1972. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/81787 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Cardoso, R.M.; Soares, P.M.M.; Cancela, J.J.; Pinto, J.G.; Santos, J.A. Integrated analysis of climate, soil, topography and vegetative growth in Iberian viticultural regions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orden de 21 de enero de 2009, Por la que se Aprueba el Reglamento del Vino de Calidad de «Granada» y de su Órgano de Gestión. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2018/39/24 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Orden de 19 de febrero de 2018, por la que se Aprueba el Reglamento de Funcionamiento del Consejo Regulador de la Denominación de Origen Protegida «Granada». Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.dopvinosdegranada.es/_files/ugd/bf7ccb_5e45683d68ae481eb74b09c54c0c1578.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Pliego de Condiciones de la Denominación de Origen Protegida «Granada». Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.dopvinosdegranada.es/_files/ugd/bf7ccb_168a9a0d0ca7482db924a913270f4fdb.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Mansour, G.; Ghanem, C.; Mercenaro, L.; Nassif, N.; Hassoun, G.; Del Caro, A. Effects of altitude on the chemical composition of grapes and wine: A review. OENO One 2022, 56, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, L.A.; Berli, F.; Fontana, A.; Bottini, R.; Piccoli, P. Climate change effects on grapevine physiology and biochemistry: Benefits and challenges of high altitude as an adaptation strategy. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 835425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, C.R.; Molina, J.J.M.; de la Serrana, H.L.G. Relación entre las temperaturas máximas y los distintos parámetros de calidad en vinos. Ars Pharm. 2010, 51, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, V.S.; Gómez-Miguel, V.; Tonietto, J.; Almorox, J. El Clima Vitícola de las Principales Regiones Productoras de uvas para vino en España. Clima, Zonificación y Tipicidad del vino en Regiones Vitivinícolas Iberoamericanas, 199. 2012. Available online: https://www.sidalc.net/search/Record/dig-alice-doc-928660/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Datos Espaciales de Referencia de Andalucía (DERA). Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. Datos climáticos de Andalucía [Conjunto de Datos]. 2006. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/dega/datos-espaciales-de-referencia-de-andalucia-dera/descarga-de-informacion (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Laget, F.; Tondut, J.-L.; Deloire, A.; Kelly, M.T. Climate trends in a specific Mediterranean viticultural area between 1950 and 2006. OENO One 2008, 42, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Eichmeier, A.; Mattii, G.B. Effects of global warming on grapevine berries phenolic compounds—A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, J.; Martín, F.; Diez, M.; Sierra, M.; Fernández, J.; Sierra, C.; Ortega, E.; Oyonate, C. Mapa Digital de Suelos. Provincia de Granada. Dirección General para la Biodiversidad, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. Madrid. 2006. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/biodiversidad/temas/desertificacion-restauracion/memoriamapasueloslucdemegranada_tcm30-512283.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Olalla, M.; Ortega, E.; Villalón, M.; López, H.; López, M.C. Estudio de los factores naturales y humanos que definen y determinan la calidad de los vinos de la comarca granadina de la “Alpujarra-Contraviesa”. Ars Pharm. Int. 1997, 38, 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, G.; Kühl, S. Perception and acceptance of robots in dairy farming—A cluster analysis of German citizens. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S. A vision of precision agriculture: Balance between agricultural sustainability and environmental stewardship. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 1126–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.; Nyoni, Y.; Kachamba, D.J.; Banda, L.B.; Moyo, B.; Chisambi, C.; Banfill, J.; Hoshino, B. Can drones help smallholder farmers improve agriculture efficiencies and reduce food insecurity in Sub-Saharan Africa? Local perceptions from Malawi. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; Anwar, A. Transition pathways for Malaysian paddy farmers to sustainable agricultural practices: An integrated exhibiting tactics to adopt Green fertilizer. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kountios, G.; Ragkos, A.; Bournaris, T.; Papadavid, G.; Michailidis, A. Educational needs and perceptions of the sustainability of precision agriculture: Survey evidence from Greece. Precis. Agric. 2018, 19, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudari, M.B.; Patil, S.L.; Nagaratna Biradar, N.B. Relationship between socio-economic characteristics of farmers and perceived attributes of precision farming. Int. J. Agric. Stat. Sci. 2017, 13, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kudari, M.B.; Patil, S.L.; Nadagouda, B.T. Impact of precision farming practices on crop productivity and income of farmers and constraints faced by the farmers. Int. J. Agric. Stat. Sci. 2016, 12, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Study on the influence mechanism of adoption of smart farming technologies in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Adoption and diffusion of digital farming technologies: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörner, D.; Bouguen, A.; Frölich, M.; Wollni, M. Knowledge and adoption of complex agricultural technologies: Evidence from an extension experiment. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2022, 36, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvittawat, A. Investigating farmers’ perceptions of drone technology in Thailand: Exploring expectations, product quality, perceived value, and adoption in agriculture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; De Rosa, M.; Vecchio, Y.; Bartoli, L.; Adinolfi, F. The long way to innovation adoption: Insights from precision agriculture. Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Mahmood, N.; Zeb, A.; Kächele, H. Factors determining farmers’ access to and sources of credit: Evidence from the rain-fed zone of Pakistan. Agriculture 2020, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Impact of environmental regulation perception on farmers’ agricultural green production technology adoption: A new perspective of social capital. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Chaudhary, R.; Sharma, S.; Janjhua, Y.; Thakur, P.; Sharma, P.; Keprate, A. Exploring the dynamics of climate-smart agricultural practices for sustainable resilience in a changing climate. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, H. Farmers’ adoption of agriculture green production technologies: Perceived value or policy-driven? Heliyon 2024, 10, e23925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzlaff, R.; Molitor, D.; Behr, M.; Bossung, C.; Rock, G.; Hoffmann, L.; Evers, D.; Udelhoven, T. UAS-based multi-angular remote sensing of the effects of soil management strategies on grapevine. OENO One 2015, 49, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorin, B.; Reynolds, A.G.; Lee, H.S.; Carrey, M.; Shemrock, A.; Shabanian, M. Detecting cool-climate Riesling vineyard variation using unmanned aerial vehicles and proximal sensors. Drone Syst. Appl. 2023, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimati, A.; Papadopoulos, G.; Manstretta, V.; Giannakopoulou, M.; Adamides, G.; Neocleous, D.; Vassiliou, V.; Savvides, S.; Stylianou, A. Case studies on sustainability-oriented innovations and smart farming technologies in the wine industry: A comparative analysis of pilots in Cyprus and Italy. Agronomy 2024, 14, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, K.E.; Conway, D.; Hardman, M.; Nesbitt, A.; Dorling, S.; Borchert, J. Adaptation to climate change in the UK wine sector. Clim. Risk Manag. 2023, 42, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J.; Touzard, J.M. To what extent do an innovation system and cleaner technological regime affect the decision-making process of climate change adaptation? Evidence from wine producers in three wine clusters in France. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Strong, R.; Dooley, K.E. Analyzing precision agriculture adoption across the globe: A systematic review of scholarship from 1999–2020. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozambani, C.I.; de Souza Filho, H.M.; Vinholis, M.D.M.B.; Carrer, M.J. Adoption of precision agriculture technologies by sugarcane farmers in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1813–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knierim, A.; Kernecker, M.; Erdle, K.; Kraus, T.; Borges, F.; Wurbs, A. Smart farming technology innovations—Insights and reflections from the German Smart-AKIS hub. NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevas, T.; Kalaitzandonakes, N. Farmer awareness, perceptions and adoption of unmanned aerial vehicles: Evidence from Missouri. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Hoang Nguyen, L.; Halibas, A.; Quang Nguyen, T. Determinants of precision agriculture technology adoption in developing countries: A review. J. Crop. Improv. 2023, 37, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Holguín, R.R.; Vaca-Coronel, C.A.; Farías-Lema, R.M.; Zapatier-Castro, S.V.; Valenzuela-Cobos, J.D. Smart agriculture in Ecuador: Adoption of IoT technologies by farmers in Guayas to improve agricultural yields. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Leduc, G.; Manevska-Tasevska, G.; Toma, L.; Hansson, H. Farmers’ adoption of ecological practices: A systematic literature map. J. Agric. Econ. 2024, 75, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thematic Block | Included Variables | Associated Construct |

|---|---|---|

| Surveyed Profile | Age, gender, educational level, years of experience in viticulture, sources of income | Control/Context Variables |

| Vineyard Characteristics | Geographic location, cultivated area (ha), yield, PDO (Protected Designation of Origin)/PGI (Protected Geographical Indication) membership | Structural Variables |

| Decision-Making Influencing Factors | Environmental factors, production profitability, labor availability, soil erosion, investment, subsidies | Adoption Determinants |

| Risk Assessment and Perceptions | Degree of concern about climate change, erosion, labor availability, yield, price | Perception → perceived usefulness/urgency |

| Soil Management Priorities | Production, plant health, soil health | Perception → priorities and trade-offs |

| Current Technologies | Use of technological tools (yes/no), adoption of ability to use them (yes/no) | Adoption → current use |

| Future Willingness | Interest in implementing new tools and desired features in applications | Adoption → intention to adopt |

| Type of Perception | Number of Articles | Main Identified Reasons |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 38 | Acceptance and satisfaction due to improvements in productivity, cost reduction, input optimization, and environmental benefits. Technology is perceived as useful and economically viable, especially when accompanied by training or incentives. |

| Negative | 3 | Rejection arising from high costs, regulatory barriers, lack of training, or perception of technological complexity. In some cases, it is associated with frustration over the lack of immediate results or distrust toward new tools. |

| Neutral | 5 | Indeterminate opinions or absence of explicit evaluation of the technology. Observed when articles do not directly measure perception, or when farmers lack sufficient experience to make a clear judgment. |

| Mixed | 51 | Coexistence of positive and negative aspects in technology adoption. Perceived usefulness and environmental benefits are highlighted, but difficulties related to costs, lack of training, infrastructure limitations, or risk of technological dependence are also noted. The diversity of productive and socioeconomic contexts explains the prevalence of this category. |

| Variable | Summary Description |

|---|---|

| Age | Mean: 62 years; range: 36–87 years |

| Gender | Male: 27 (73%); Female: 10 (27%) |

| Educational level | No studies: 6 (16%) Primary: 6 (16%) Secondary: 8 (22%) Vocational Training: 3 (8%) University degree: 12 (32%) Master/Doctorate: 2 (5%) |

| Viticulture experience | Mean: 25 years; range: 5–50 years |

| Economic dependence on vineyard | Vineyard as main economic source: 3 (8%) Vineyard as supplementary economic source: 34 (92%) |

| Factor Category | Variables Included | Perceived Importance * | Interpretative Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Production profitability, initial investment, availability of machinery, and technical resources | High | These are the most determining criteria; they highlight economic viability and conditions for the capacity for innovation. |

| Environmental | Soil erosion, water availability, drought | Medium–High | Highly influential factors in high-altitude areas and vulnerable plots; they reflect a growing environmental concern |

| Productive/structural | Vineyard scale, membership in PDO, diversification with other crops | Variable | They condition management strategy; small vineyards tend to prioritize low-cost solutions. |

| Area of Focus | Number of Responses * | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Production | 10 | 27 |

| Plant (vineyard) | 22 | 59 |

| Soil | 5 | 14 |

| Vineyard Size | Certification (PDO/PGI) | Current Use of Technology | Future Willingness to Use App |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 ha (Total = 20) | None | (0/17) | (9/17) |

| PDO or PGI | (0/3) | (2/3) | |

| 1–5 ha | None | (0/3) | (2/3) |

| (Total = 11) | PDO or PGI | (0/8) | (6/8) |

| 5–10 ha | None | - | - |

| (Total = 2) | PDO or PGI | (1/2) | (2/2) |

| >10 ha | None | - | - |

| (Total = 4) | PDO or PGI | (2/4) | (3/4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Vivar, J.; Sobczyk, R.; Romero-Frías, E.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Adoption and Perception of Precision Technologies in Agriculture: Systematic Review and Case Study in the PDO Wines of Granada, Southern Spain. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232468

González-Vivar J, Sobczyk R, Romero-Frías E, Rodrigo-Comino J. Adoption and Perception of Precision Technologies in Agriculture: Systematic Review and Case Study in the PDO Wines of Granada, Southern Spain. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232468

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Vivar, Jesús, Rita Sobczyk, Esteban Romero-Frías, and Jesús Rodrigo-Comino. 2025. "Adoption and Perception of Precision Technologies in Agriculture: Systematic Review and Case Study in the PDO Wines of Granada, Southern Spain" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232468

APA StyleGonzález-Vivar, J., Sobczyk, R., Romero-Frías, E., & Rodrigo-Comino, J. (2025). Adoption and Perception of Precision Technologies in Agriculture: Systematic Review and Case Study in the PDO Wines of Granada, Southern Spain. Agriculture, 15(23), 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232468