Impact-Induced Breakage Behavior During Grain Discharge and Modeling Framework for Discharge Impact Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Materials and Equipment

2.2. Simulation Method Description

2.2.1. Mechanical Contact Model

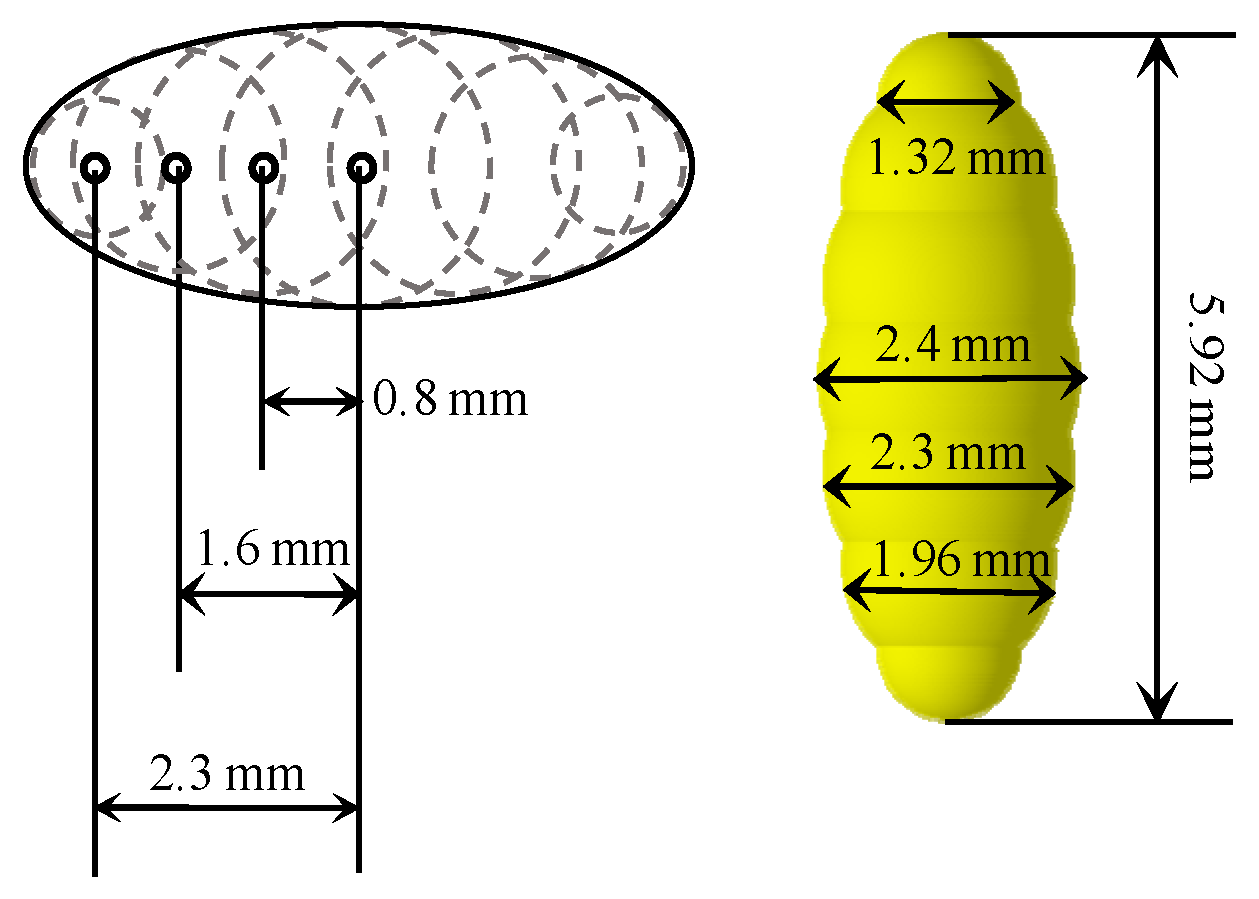

2.2.2. DEM Model of Particle and Geometry

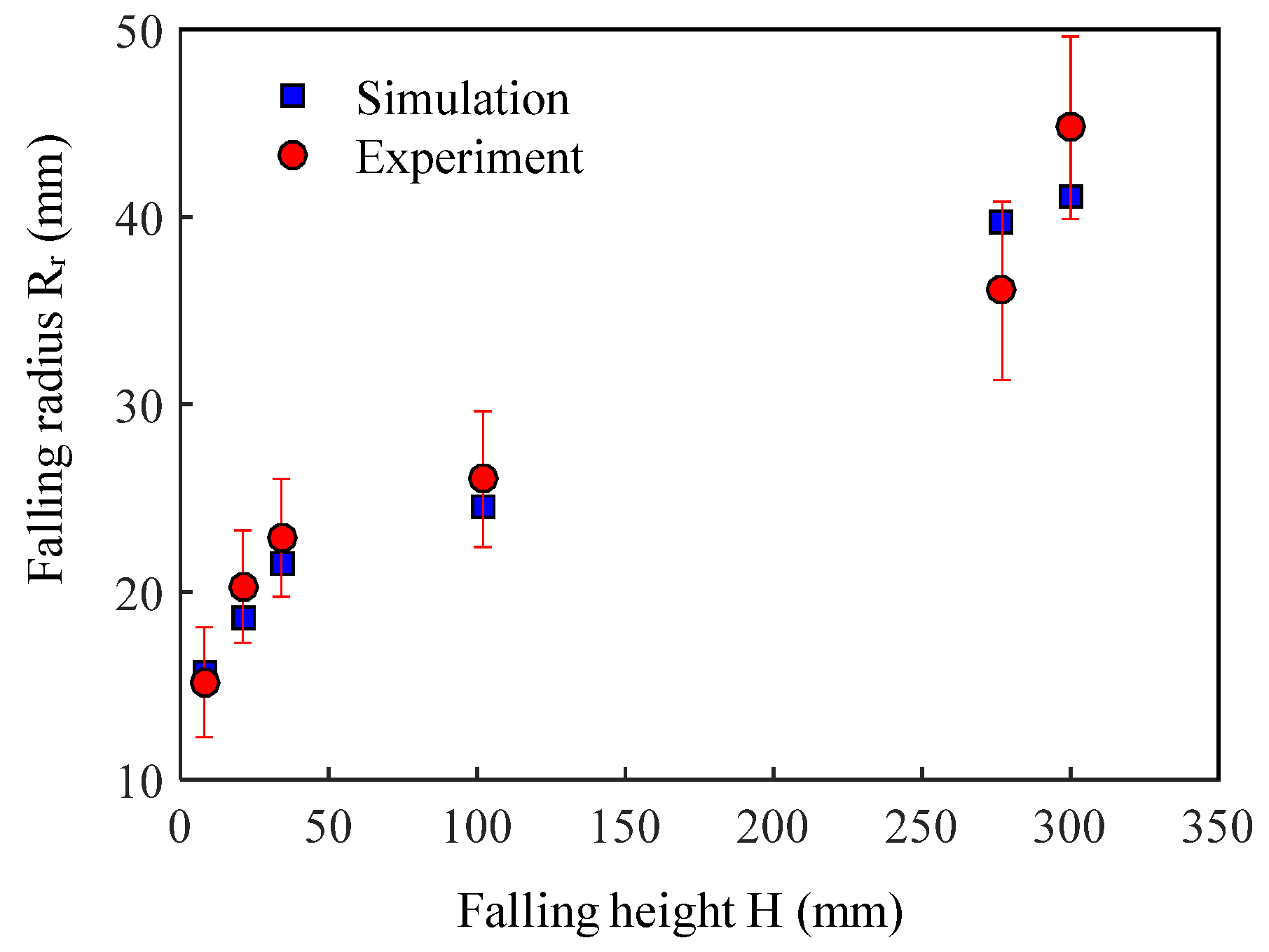

2.3. Validation of the Simulation Results

3. Results

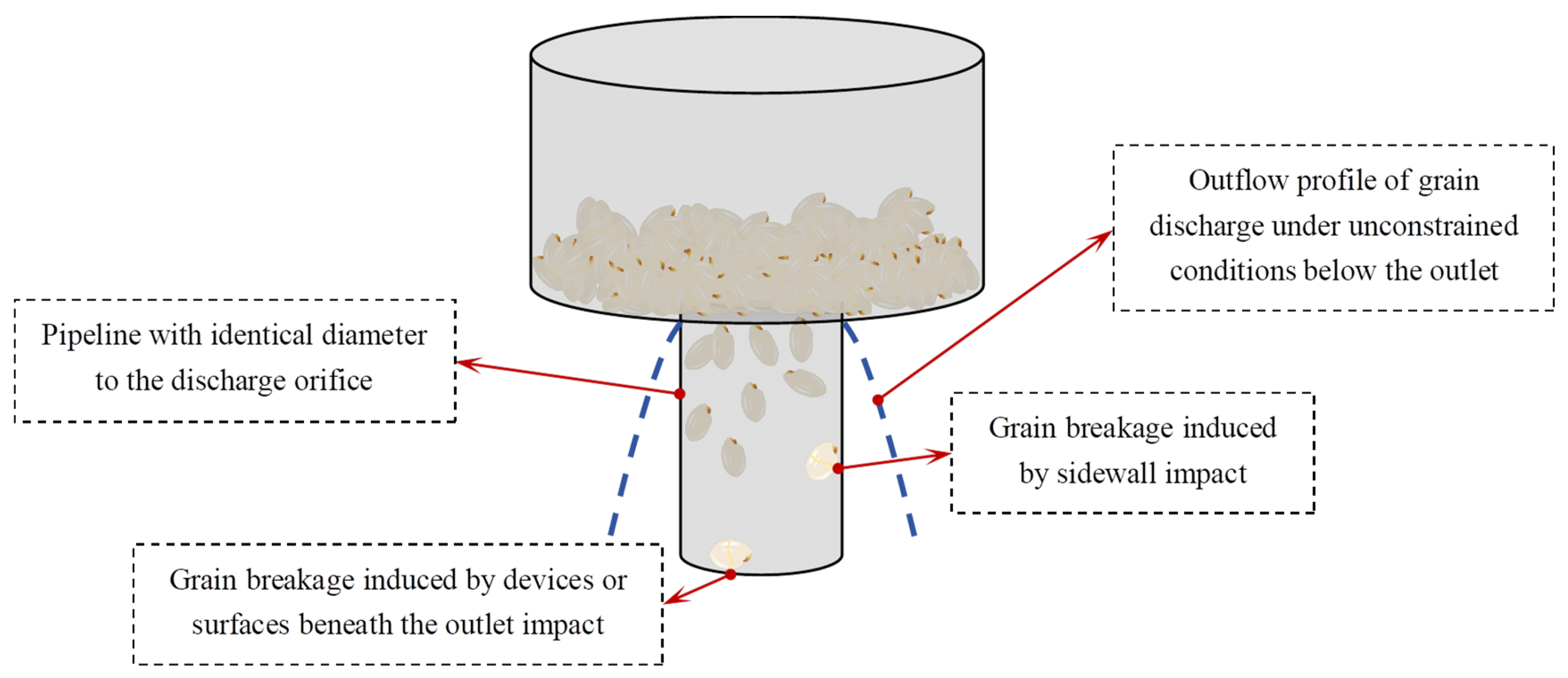

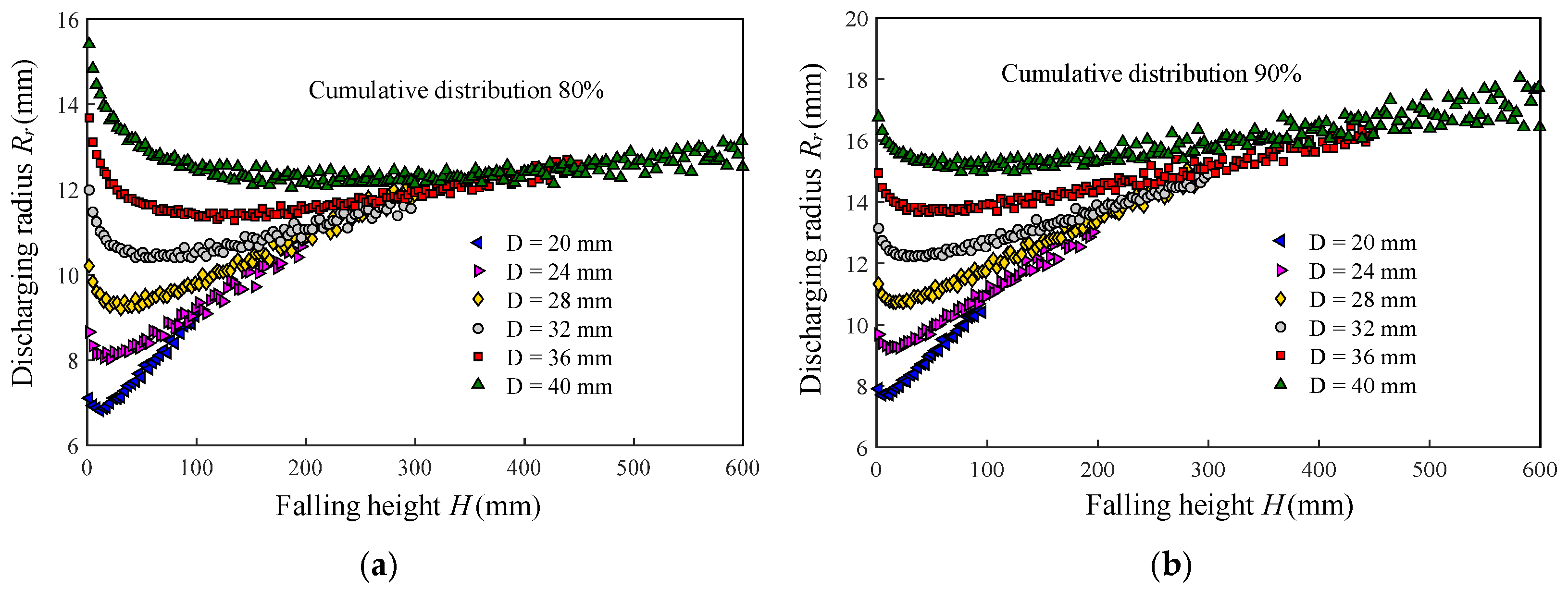

3.1. Outflow Profile Characteristics Corresponding to Different Discharging Ranges

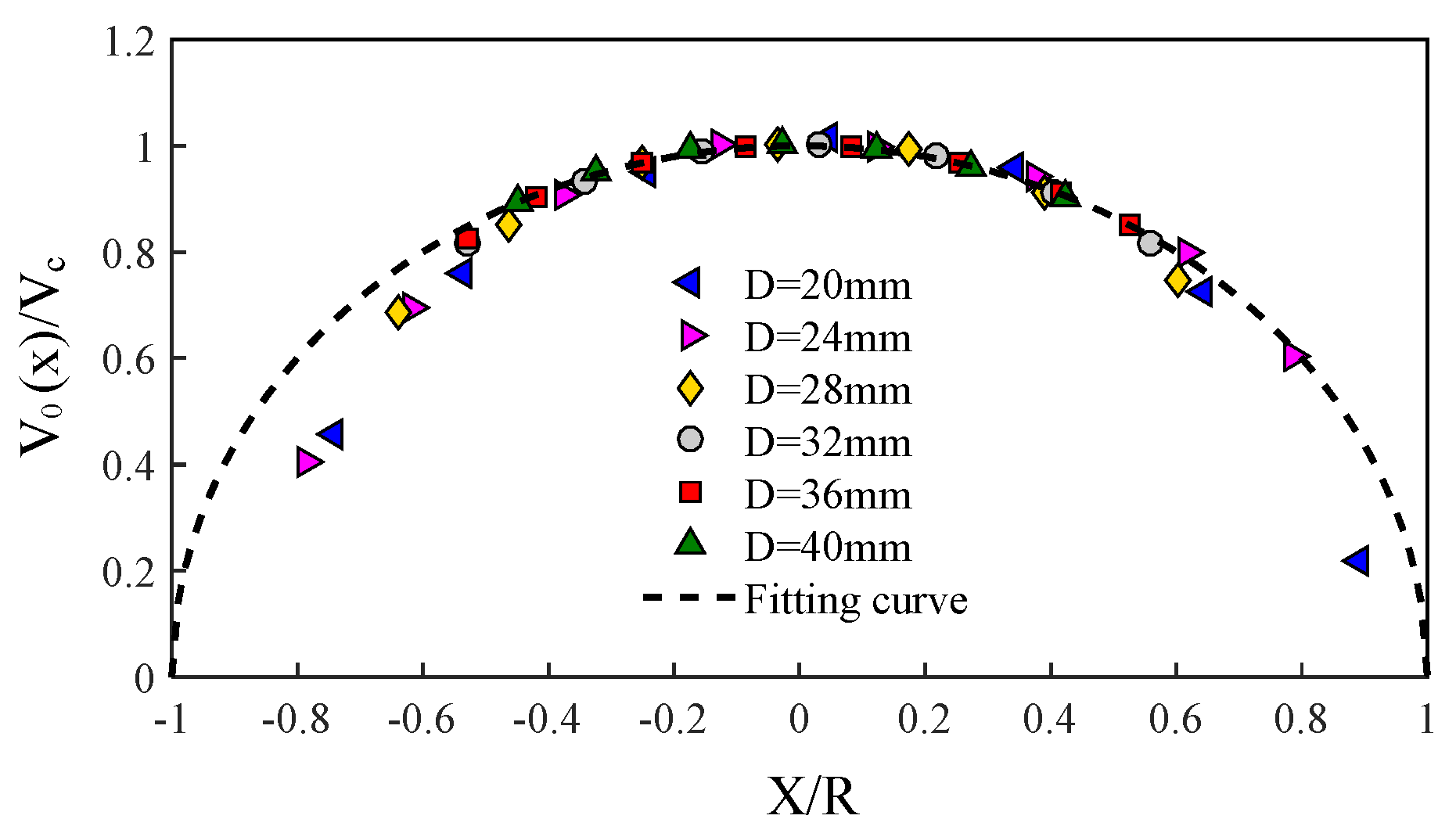

3.1.1. Quantifying Grain Outflow Profiles

3.1.2. Grain Velocity and Orientation During Discharge Processes

3.1.3. Predictive Model for Grain Impact Velocity During Discharge Processes

3.2. Effect of Grain Outflow Impact on Kernel Breakage

Critical Breakage Thresholds of Brown Rice Under Varying Impact Velocities

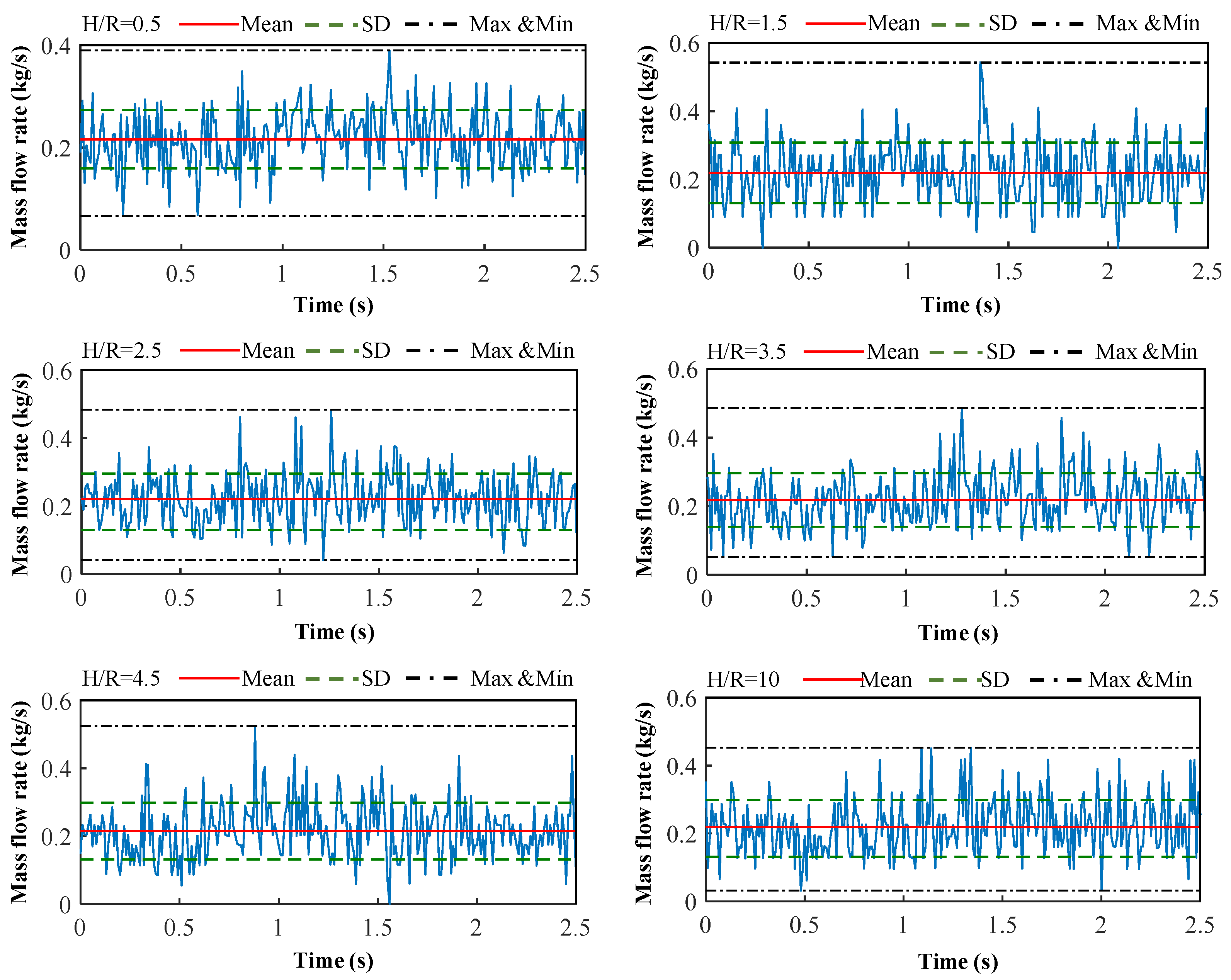

3.3. Prediction of Grain Outflow Impact Force and Pressure During Discharge Processes

4. Conclusions

- Distinct discharge ranges correspond to differential grain outflow characteristics. The variation patterns of grain falling velocity and attitude for different discharge ranges during the discharging process were analyzed. The results indicate negligible differences in falling velocity between core and boundary layers, while the primary distinction in impact behavior across discharge ranges manifests in grain attitude upon impact. Core layer grains exhibit minimal angles relative to the sidewalls while maintaining near-vertical with respect to the horizontal plane below the outlet. In contrast to the core layer, boundary layer grains exhibit smaller inclination angles relative to the horizontal plane while maintaining larger angles (approximately 60°) with respect to the sidewalls.

- A predictive model for average grain falling velocity was developed. Based on the single-grain breakage probability model, critical unit mass impact energy (along 90°: 106.4 J kg−1; along 0°: 57.28 J kg−1) and critical breakage velocity (along 90°: 14.59 m s−1; along 0°: 10.70 m s−1) were determined under two extreme impact attitude conditions. A comprehensive analysis of grain attitude and impact velocity variation with falling height during discharge, combined with the critical collision energy per unit mass for brown rice breakage, enabled the development of a breakage probability zoning diagram for grain impact during both the large-scale and small-scale discharge processes.

- Theoretical prediction models were successfully developed for key engineering design parameters including mass flow rate, impact force, and impact pressure during grain discharging processes. These models were subsequently validated, with the verification results demonstrating excellent predictive capabilities across all constructed models. This study can provide critical design parameters for discharge systems to prevent grain impact breakage during discharging progresses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, S.; Lei, X.P.; Wu, H.Q.; Li, H.; Song, H.Y.; Zheng, D.C.; Jiawei, W.; Li, A.B.; Farid, M.U.; Ghafoor, A. Optimizing the design of a multi-stage tangential roller threshing unit using CFD modeling and experimental studies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lian, Y.; Zou, R.; Zhang, S.; Ning, X.B.; Han, M.N. Real-time grain breakage sensing for rice combine harvesters using machine vision technology. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, L.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.N. Impact of kernel breakage and storage conditions on mildew growth in grain piles. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2025, 42, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, Z.; Mason, S.; Babic, M.; Vitazek, I.; Pliestic, S.; Srecec, S.; Kovacev, I.; Habus, M. Factors influencing maize kernel breakage—A review. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2024, 25, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansart, R.; de Ryck, A.; Dodds, J.A. Dust emission in powder handling: Free falling particle plume characterisation. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 152, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Fan, H.F.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, J.J.; Cui, T.; Su, Y.; Qiao, M.M.; Han, S.Y.; Qian, J. Decreasing grain processing breakage with a novel flexible threshing system: Multivariate optimization and wear investigation. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.S.; Someswararao, C.; Das, S.K. Pneumatic polishing of rice in a horizontal abrasive pipe: A new approach in rice polishing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014, 22, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Opara, L.U.; Hampton, J.G.; Hardacre, A.K.; MacKay, B.R. PH—Postharvest Technology: The Effects of Grain Temperature on Breakage Susceptibility in Maize. Biosyst. Eng. 2002, 82, 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Li, A.Q.; Ji, S.Y.; Li, H.; Li, Z.Z.; Gao, H.N.; Wang, X.L.; Li, X.L.; Han, Y.L.; Zhao, D. A method for improving milling quality based on pre-milling in the combined rice milling process. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 100, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.J.; Narendran, R.B.; Jayas, D.S. Segregation in stored grain bulks: Kinematics, dynamics, mechanisms, and minimization—A review. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2019, 81, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.Y.; Xu, Y.; Su, Y.; Gao, X.J.; Li, Y.B.; Qiao, M.M.; Yu, Y.B. Feature selection, artificial neural network prediction and experimental testing for predicting breakage rate of maize kernels based on mechanical properties. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, e13621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszelnicka, W.; Leda, P.; Tomporowski, A.; Ambrose, K. Breakage behavior of corn kernels subjected to repeated loadings. Powder Technol. 2024, 435, 119372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Jia, F.G.; Zhang, J.C.; Han, Y.L.; Li, A.Q.; Wang, Y.L.; Fei, J.M.; Shen, S.H.; Feng, W.Y.; Hao, X.Z. Breakage mechanism of brown rice grain during rubber roll hulling. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 225, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.H.; Ji, S.Y.; Zhao, D.; Han, Y.L.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.Z.; Li, A.Q.; Feng, W.Y.; Fei, J.M.; et al. Simulation of rice grain breakage process based on Tavares UFRJ model. Particuology 2024, 93, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.Z.; Nadolski, S.; Sun, C.B.; Klein, B.; Kou, J. The effect of strain rate on particle breakage characteristics. Powder Technol. 2018, 339, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Zhao, D.; Chu, Y.H.; Zhen, J.X.; Li, G.R.; Zhao, H.W.; Jia, F.G. Breakage behaviour of single rice particles under compression and impact. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 4635–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.N.; Hou, L.Y.; Li, L.L.; Gao, S.; Hou, J.F.; Ming, B.; Xie, R.Z.; Xue, J.; Hou, P.; Wang, K.R.; et al. Study of corn kernel breakage susceptibility as a function of its moisture content by using a laboratory grinding method. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.D.; Cirilo, A.G.; Cerrudo, A.A.; Andrade, F.H.; Izquierdo, N.G. Environment affects starch composition and kernel hardness in temperate maize. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 5488–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Jia, F.G.; Xiao, Y.W.; Han, Y.L.; Meng, X.Y. Discrete element method modelling of impact breakage of ellipsoidal agglomerate. Powder Technol. 2019, 346, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Z.; Li, Y.M.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.H. Theoretical analysis and finite element simulation of a rice kernel obliquely impacted by a threshing tooth. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.W.; Han, Y.L.; Jia, F.G.; Liu, H.R.; Li, G.R.; Chen, P.Y.; Meng, X.Y.; Bai, S.G. Research on clogging mechanisms of bulk materials flowing trough a bottleneck. Powder Technol. 2021, 381, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, G.; Marsili, M. Clogging and self-organized criticality in complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 035105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaili, A.A.; Donohue, T.J.; Wheeler, C.A.; McBride, W.M.; Roberts, A.W. On the analysis of a coarse particle free falling material stream. Int. J. Miner. Process 2015, 142, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, S.L.; Zhang, L.Q.; Chew, J.W. DEM study on the discharge characteristics of lognormal particle size distributions from a conical hopper. Aiche J. 2018, 64, 1174–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Gan, J.Q.; Yu, A.B.; Pinson, D.; Zhou, Z.Y. Segregation of granular binary mixtures with large particle size ratios during hopper discharging process. Powder Technol. 2020, 361, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.C.; Specht, E.; Herz, F.; Knabbe, J.; Sprinz, U. Experimental investigation of the axial discharging velocity of particles from rotary kilns. Granul. Matter 2011, 13, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Jia, F.G.; Xiao, Y.W.; Han, Y.L.; Zeng, Y.; Li, A.Q. Effect of operating parameters on milling quality and energy consumption of brown rice. J. Food Sci. Technol.-Mysore 2019, 56, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.Q.; Jia, F.G.; Han, Y.L.; Chen, P.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.C.; Hao, X.Z.; Fei, J.M.; Shen, S.H.; Feng, W.Y. Study on dynamic response mechanism of rice grains in friction rice mill and scale-up approach of parameter based on discrete element method. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 86, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.Q.; Jia, F.G.; Shen, S.H.; Han, Y.L.; Chen, P.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.C.; Feng, W.Y.; Fei, J.M.; Hao, X.Z. Numerical simulation approach for predicting rice milling performance under different convex rib helix angle based on discrete element method. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 83, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Jia, F.G.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, L.W.; Zhang, Y.X.; Cao, B. DEM study of particle conveying in a feed screw section of vertical rice mill. Powder Technol. 2017, 311, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.W.; Han, Y.L.; Jia, F.G.; Liu, H.R.; Li, G.R.; Chen, P.Y.; Meng, X.Y.; Bai, S.G. Experimental study of granular flow transition near the outlet in a flat-bottomed silo. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 202, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.G.; Liu, H.F.; Li, W.F.; Xu, J.L. The characteristics of the near field of the granular jet. Fuel 2014, 115, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.H.; Li, W.F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.F.; Wang, F.C. DEM study of liquid-like granular film from granular jet impact. Powder Technol. 2018, 336, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, A.; Zuriguel, I.; Maza, D. Flow Rate of Particles through Apertures Obtained from Self-Similar Density and Velocity Profiles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 248001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, L.; Peukert, W. Breadage behaviour of different materials—Construction of mastercurve for the breakage probability. Powder Technol. 2003, 129, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, H. Physical aspects of comminution and new formulation of a law of comminution. Powder Technol. 1973, 7, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Brown Rice Particle | Density ρr (kg/m3) | 1333 |

| Poisson ratio vr | 0.25 | |

| Shear modulus Gr (Pa) | 3.75 × 108 | |

| Silo | Density ρs (kg/m3) | 1500 |

| Poisson ratio vs | 0.4 | |

| Shear modulus Gr (Pa) | 1 × 108 | |

| Silo diameter Ds (mm) | 100 | |

| Outlet diameter D (mm) | 20~40 | |

| Particle–Particle | Restitution coefficient eRR | 0.6 |

| Coefficient of static friction μs,RR | 0.3 | |

| Coefficient of rolling friction μr,RR | 0.01 | |

| Particle–Silo | Restitution coefficient eRS | 0.5 |

| Coefficient of static friction μs,RS | 0.5 | |

| Coefficient of rolling friction μr,RS | 0.02 | |

| Simulation | Time step Δt (s) | 8.52 × 10−7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, A.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xi, X.; Zhang, R. Impact-Induced Breakage Behavior During Grain Discharge and Modeling Framework for Discharge Impact Prediction. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222368

Xiao Y, Sun M, Li A, Han Y, Zhao Y, Xi X, Zhang R. Impact-Induced Breakage Behavior During Grain Discharge and Modeling Framework for Discharge Impact Prediction. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222368

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Yawen, Minyue Sun, Anqi Li, Yanlong Han, Yanqin Zhao, Xiaobo Xi, and Ruihong Zhang. 2025. "Impact-Induced Breakage Behavior During Grain Discharge and Modeling Framework for Discharge Impact Prediction" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222368

APA StyleXiao, Y., Sun, M., Li, A., Han, Y., Zhao, Y., Xi, X., & Zhang, R. (2025). Impact-Induced Breakage Behavior During Grain Discharge and Modeling Framework for Discharge Impact Prediction. Agriculture, 15(22), 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222368