1. Introduction

Sugar beet (

Beta vulgaris L.) is one of the most important industrial crops cultivated in temperate regions, providing a major global source of sucrose. It accounts for approximately 20% of the world’s sugar production. The key growing areas are located in Europe, North America, and Asia. The crop’s economic value depends not only on root yield but also on its technological quality, which directly influences sugar extraction efficiency [

1,

2]. Sugar beet root yield and processing quality result from complex interactions between the genetic potential of the cultivar, seed quality, environmental conditions, and cultivation practices [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Among these, seed quality plays a particularly critical role in promoting fast, uniform emergence and robust early growth, key determinants of the final yield [

8,

9,

10].

One widely recognized method for improving seed performance is seed priming, a controlled hydration process that initiates metabolic activity without triggering radicle emergence [

11,

12]. Priming is usually performed using water-saturated solid carriers or aqueous solutions under specific moisture and time conditions, allowing early germination stages to begin while avoiding seed damage [

13]. Recent insights into the physiological mechanisms of seed priming suggest that metabolic reactivation during hydration leads to selective gene expression, antioxidant activation, and early repair of cellular structures [

12,

14]. In sugar beet, priming has been shown to increase mesopore diameter in the pericarp, enhancing the water potential gradient and accelerating imbibition [

15]. Moreover, polishing and washing during seed processing remove physical and chemical germination barriers, including abscisic acid (ABA) and mineral solutes, thereby improving water uptake and germination efficiency [

16,

17].

Primed seeds exhibit higher vigor, faster and more uniform germination, and greater resilience under suboptimal field conditions [

14,

18]. These effects have been confirmed across several crops, including maize, spinach and rice [

19,

20,

21]. Growers frequently report enhanced crop uniformity, faster early growth, and improved weed suppression, thanks to synchronized emergence and more consistent root size, which also facilitates harvesting [

22]. In cold soil conditions, seed priming has been associated with improved membrane integrity, increased α-amylase and catalase activity, and reduced oxidative stress during early seedling growth [

10,

23].

In addition to sugar beet, seed priming has been applied in other root and industrial crops. For instance, Zhao et al. [

24] demonstrated that a hydro-electro hybrid priming (HEHP) method significantly improved germination and early growth of carrot (

Daucus carota L.) under variable moisture conditions. Similarly, a study in

Brassica napus by Kubala et al. [

25] showed that priming treatments enhanced emergence rates and seedling vigor under both optimal and stress conditions. More recently, Das et al. [

26] reported field results in rapeseed-mustard, indicating yield and growth benefits from chemical priming in multi-year trials. These findings suggest that priming benefits can extend beyond model species to crops of economic importance. However, despite these advances, field-based assessments in sugar beet remain scarce, especially in linking priming to canopy architecture and technological sugar yield.

In recent decades, sugar beet sowing in Europe has shifted earlier by 10–20 days to extend the growing season and boost yield. A 13-day extension of the growing period has been shown to increase root yield by up to 10.9% [

27]. However, early sowing under cool soil conditions requires seeds with enhanced germination potential, needs that can be effectively addressed through seed priming [

28].

Although seed priming is recognized as an effective technique for improving germination and early plant performance, its practical implementation still faces certain limitations. The effectiveness of priming depends on the interaction between species, cultivar, and environmental conditions, while over-hydration or improper drying may impair germination performance. Moreover, primed seeds often exhibit reduced storability and should be sown shortly after treatment to maintain vigor and uniform emergence [

21]. These aspects should be considered when evaluating the practical application and reproducibility of priming effects under field conditions.

Despite its benefits, the field-level effects of seed priming in sugar beet remain underexplored, particularly in the context of canopy development and yield stability under variable environmental conditions. Uniform and rapid emergence is essential for establishing optimal sugar beet plant spacing and root architecture. Uneven or delayed emergence leads to high variability in sugar beet root mass at harvest, as late-emerging plants typically lag behind in development and accumulate less biomass [

29,

30]. This variation reduces processing efficiency and complicates harvest timing. Priming supports early canopy closure, regular in-row spacing, and greater leaf area development, all factors that contribute to higher radiation interception and biomass accumulation [

31,

32]. It also improves juice quality by reducing concentrations of molasses-forming substances (Na

+, K

+, α-amino-N), which increases sugar recovery and processing efficiency [

33]. Ultimately, the effectiveness of seed priming is best measured by improvements in final sugar beet root and sugar yield. Earlier sowing made possible by priming has been associated with sugar yield increases of up to 5%. In the UK, the use of primed seed led to a 50% reduction in emergence time, a 4% increase in root yield, and a 5% increase in sugar yield [

10,

34].

This study was undertaken to assess how sugar beet seed priming affects plant emergence, canopy structure, root yield, and technological sugar yield under field conditions in central Poland over three growing seasons. Particular attention was paid to emergence uniformity, early spatial arrangement, and biomass accumulation as potential drivers of yield stabilization. Our hypothesis was that priming would enhance field emergence consistency and promote uniform sugar beet canopy development, thereby reducing variability in root size and increasing both biological and technological sugar yield under temperate and variably moist conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

A three-year (2022–2024) field experiment with sugar beet (

Beta vulgaris L.) was carried out at the Experimental Field in Miedniewice (51°97′ N, 20°19′ E) in central Poland. The site is part of the Experimental Station of the Institute of Agriculture, Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW, located in Skierniewice. The experiment was conducted on Luvisols, as defined by the World Reference Base for Soil Resources [

35], specifically rainfall-gley podzolic soils developed from light and heavy loamy sands overlying lighter subsoils. The soils were slightly acidic (pH = 5.8) and contained high levels of phosphorus (70 mg·kg

−1), along with medium levels of potassium (90 mg·kg

−1) and magnesium (50 mg·kg

−1).

2.2. Weather Conditions

Meteorological data for each growing season are summarized in

Table 1. Weather conditions varied considerably among years, influencing sugar beet growth and yield formation. In 2022, total precipitation (343.2 mm) was well below crop requirements, and low Sielianinov hydrothermal coefficient (Hk) values (<1.0) in May and July indicated drought stress during critical stages, which hindered emergence and biomass accumulation. The 2023 season was markedly wetter (474.9 mm, Hk up to 2.8), providing favorable hydrothermal conditions that promoted vigorous canopy development and higher root biomass, particularly in primed treatments. In 2024, total rainfall (406.8 mm) was close to the long-term mean, but uneven distribution with dry periods in May, September, and October caused temporary water deficits affecting early growth and final yield. Across all three years, plants from primed seeds showed more stable performance under both moisture deficit and surplus conditions. Optimal temperature conditions for sugar beet root yield formation are typically in the range of 15–22 °C, while temperatures above 25 °C or below 10 °C may limit assimilate accumulation and reduce root growth [

3].

The experiment was conducted at a single, representative site to minimize management and soil variability and to allow precise attribution of observed differences to the priming treatment. Conducting the trial at one site across three climatically contrasting years provided a controlled framework to test treatment robustness under naturally varying weather conditions.

2.3. Experimental Design

The study was designed as a one-factor field experiment arranged in four replications. The experimental factor was the method of seed treatment, involving two types of seed material of the same sugar beet cultivar (Beta vulgaris L. cv. Jampol Rh + CR): standard, non-primed seeds and seeds subjected to pre-sowing priming (primed). Jampol Rh + CR cultivar bred by the Kutno Sugar Beet Breeding Company in Straszków (KHBC, Poland). It is resistant to rhizomania and Cercospora leaf spot, represents the normal (N) type, and is characterized by high root yield and high technological sugar yield, with low levels of molasses-forming components in the roots. The Jampol Rh + CR cultivar was selected because of its high yield potential, stable performance across environments, and resistance to rhizomania and Cercospora beticola. The use of a disease-resistant cultivar minimized biotic stress effects, allowing the physiological impact of seed priming to be evaluated more precisely. A single cultivar was deliberately chosen to minimize genotypic variability and avoid confounding treatment effects, ensuring that observed differences could be attributed primarily to seed priming rather than genetic diversity. Seed priming was performed using the proprietary Quick Beet (QB) method developed by KHBC (Poland), which is based on solid matrix priming (SMP) using zeolites as water carriers to enable controlled water uptake (Patent No. P207240). During the priming process, seed moisture was maintained at 40–45% (w/w) and temperature at 15–18 °C for 72 h. After hydration, seeds were gradually dried under ambient air circulation until the moisture content reached approximately 8–9%, ensuring restoration of storability and preventing radicle protrusion. The study was conducted as a single-factor experiment comparing primed (Quick Beet) and non-primed seeds. This design allowed for the assessment of the physiological and agronomic effects of seed priming without additional treatment interactions. The Quick Beet technology was selected as a representative and commercially relevant priming method used in sugar beet seed production. Both primed and non-primed seeds were pelleted using standard KHBC procedures. Seeds were sown each year on 15 April. The experiment consisted of eight plots. Each plot had an area of 27.0 m2 (10 m in length × 6 rows × 0.45 m row spacing). Sowing was carried out using a precision drill, with an in-row seed spacing of 18 cm and a sowing depth of 2.5 cm. This corresponds to a sowing density of approximately 12.3 seeds m−2 (123,000 seeds ha−1). The seeding rate was selected to ensure an optimal final plant density of about 10–11 plants m−2, which is considered optimal for achieving maximum root and sugar yield in sugar beet under temperate field conditions. In each year of the study, winter wheat was used as the preceding crop. After harvest, the field underwent post-harvest cultivation, including stubble breaking with a harrow. Organic fertilization was applied in the form of cattle manure at a rate of 35 t·ha−1. Additionally, mineral fertilizers were applied to supply 35 kg·ha−1 of phosphorus (P) and 133 kg·ha−1 of potassium (K). All fertilizers were incorporated into the soil during autumn plowing to a depth of 25–30 cm using a non-inverting moldboard plow. The nitrogen dose of 120 kg N·ha−1 was applied entirely in the form of ammonium nitrate (34%) a few days before sowing, in accordance with the experimental design. Appropriate pesticides were applied to control weeds, pests, and diseases. If necessary, manual weeding was conducted.

The experiment was conducted at a single representative site to minimize management and soil variability and to allow precise attribution of observed differences to the priming treatment

2.4. Plant Sampling and Measurements

Within each plot, a 10 m row was designated for the assessment of the following sugar beet plant and canopy traits: (1) emergence date of individual plants (expressed as days from sowing to emergence); (2) variation in growth and development during the juvenile phase (number of leaves per plant 50 days after sowing); (3) individual plant living area—calculated as the product of half the distance to the nearest plant on either side within the row and the fixed inter-row spacing of 45 cm; (4) location centrality index—the ratio of the shorter to the longer side of the plant’s occupied space, a:b; and (5) leaf and root mass (g), determined at harvest.

Plant emergence was monitored daily on designated row sections, beginning from the first day of emergence. Newly emerged sugar beet plants were marked each day using a different label color, allowing precise tracking of emergence dynamics. For each sugar beet plant, the date of emergence and its location within the row (measured as the distance from a fixed 0–1000 cm scale) were recorded, enabling consistent identification of individual sugar beet plants throughout the growing season. Fifty days after sowing, variation in juvenile plant development was evaluated by counting the number of leaves on each previously identified sugar beet plant. At the same time, the living area and location centrality index were calculated for each individual. At harvest, sugar beet plants were relocated based on their original position in the row and earlier trait records. Each plant was then manually excavated, cleaned, topped, and weighed to determine individual leaf and root mass.

Sugar beet root yield, final plant density, and average root mass were determined at harvest based on the remaining five rows per plot, corresponding to an area of 22.5 m

2. After topping, the roots were excavated, cleaned, counted, and weighed. These data were used to calculate the number of sugar beet plants and total root mass per plot, which were then converted to final plant density (thousand plants·ha

−1), root yield (t·ha

−1), and average root mass (g). In addition, a 25.0 kg sugar beet root sample was collected from each plot and analyzed using a Venema Automation beet analyzing system at the Kutno Sugar Beet Breeding Company in Straszków (Poland) to determine sucrose content (%), α-amino nitrogen, and sodium (Na

+) and potassium (K

+) ion concentrations, expressed in mmol·kg

−1 of pulp according to International Commission for Uniform Methods of Sugar Analysis (ICUMSA) guidelines. Sucrose content was determined using the polarimetric method [

38]. The Na

+ and K

+ content in sugar beet pulp was determined using the flame photometry method [

39]. The α-amino N content in beet pulp was determined using the blue colorimetric method with ninhydrin, as described by the ICUMSA Method GS6-5 [

40]. To evaluate the productivity and processing quality of sugar beet, both biological and technological sugar yields were calculated. Biological sugar yield (t·ha

−1) was determined as the product of root yield and sucrose content (%). Technological sugar yield (t·ha

−1) was calculated according to the Reinefeld formula [

41], based on root yield, sucrose concentration, and levels of molasses-forming substances (Na

+, K

+, and α-amino N).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using Statistica 13.0 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) [

42]. Basic descriptive statistics were calculated for all studied plant and canopy traits, including minimum and maximum values, means, standard deviations (SD), and coefficients of variation (CV). To assess the influence of selected plant and canopy traits on the final root mass of individual sugar beet plants, multiple linear regression was performed using standardized variables. The coefficient of multiple determination (R

2) was calculated to indicate the proportion (%) of variation in root mass (y) explained by the linear relationship with four predictor variables (x

1–x

4). In addition, standardized partial regression coefficients (b

1, b

2, b

3, b

4) were determined to quantify the independent (direct) effect of each trait on root mass. The following explanatory variables were included in the regression model: x

1—number of days from sowing to plant emergence, x

2—developmental stage at the juvenile phase (number of leaves per plant at 50 days after sowing), x

3—plant living area, x

4—location centrality index within the occupied area. To assess the effect of seed treatment on the studied traits, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, with treatment as a fixed factor and year as a random factor (blocking variable). Mean separation was conducted using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05) to ensure comparability across traits and years. For verification, Student’s

t-test was also applied for two-level comparisons, and both tests produced identical significance results.

3. Results

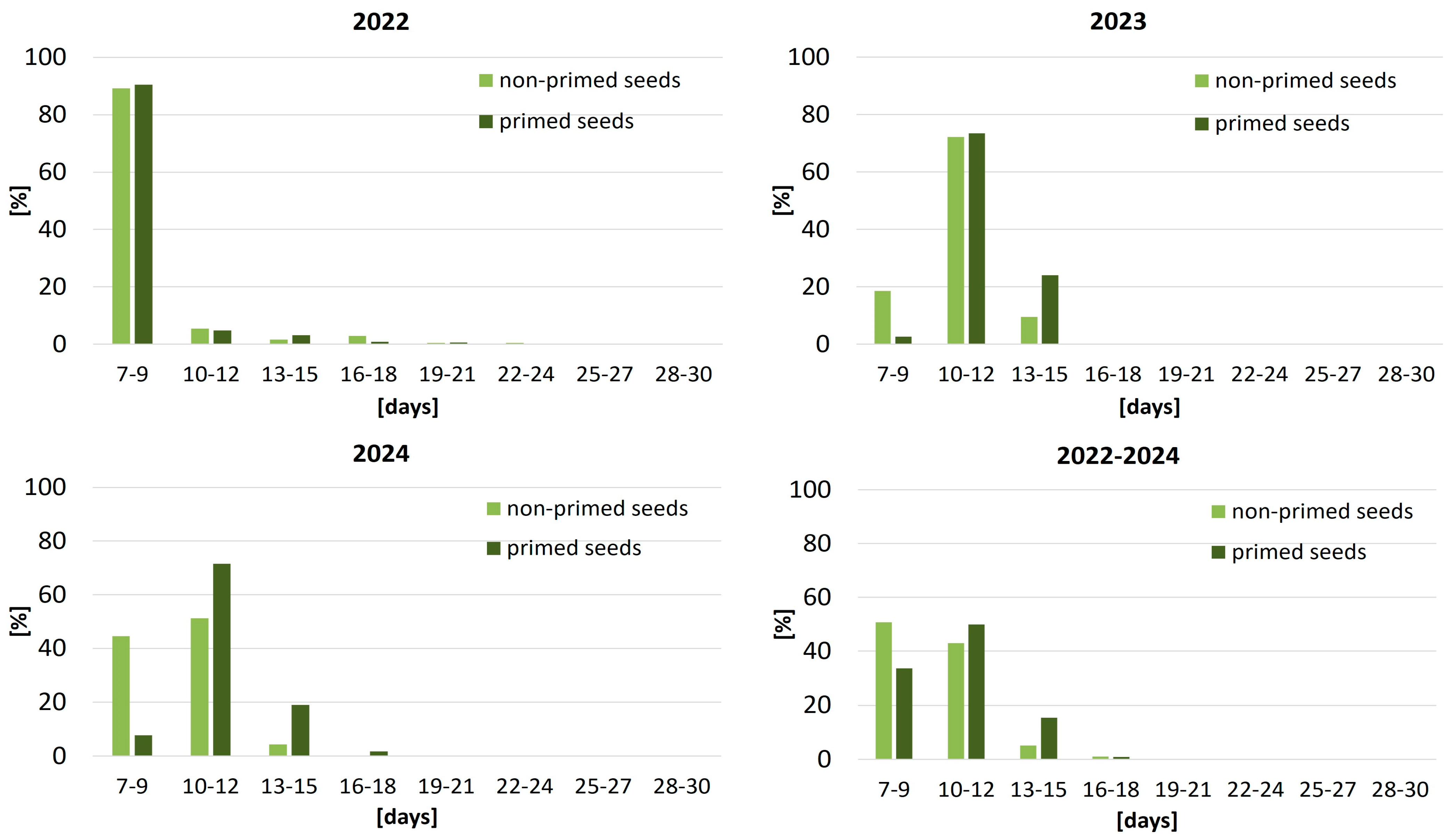

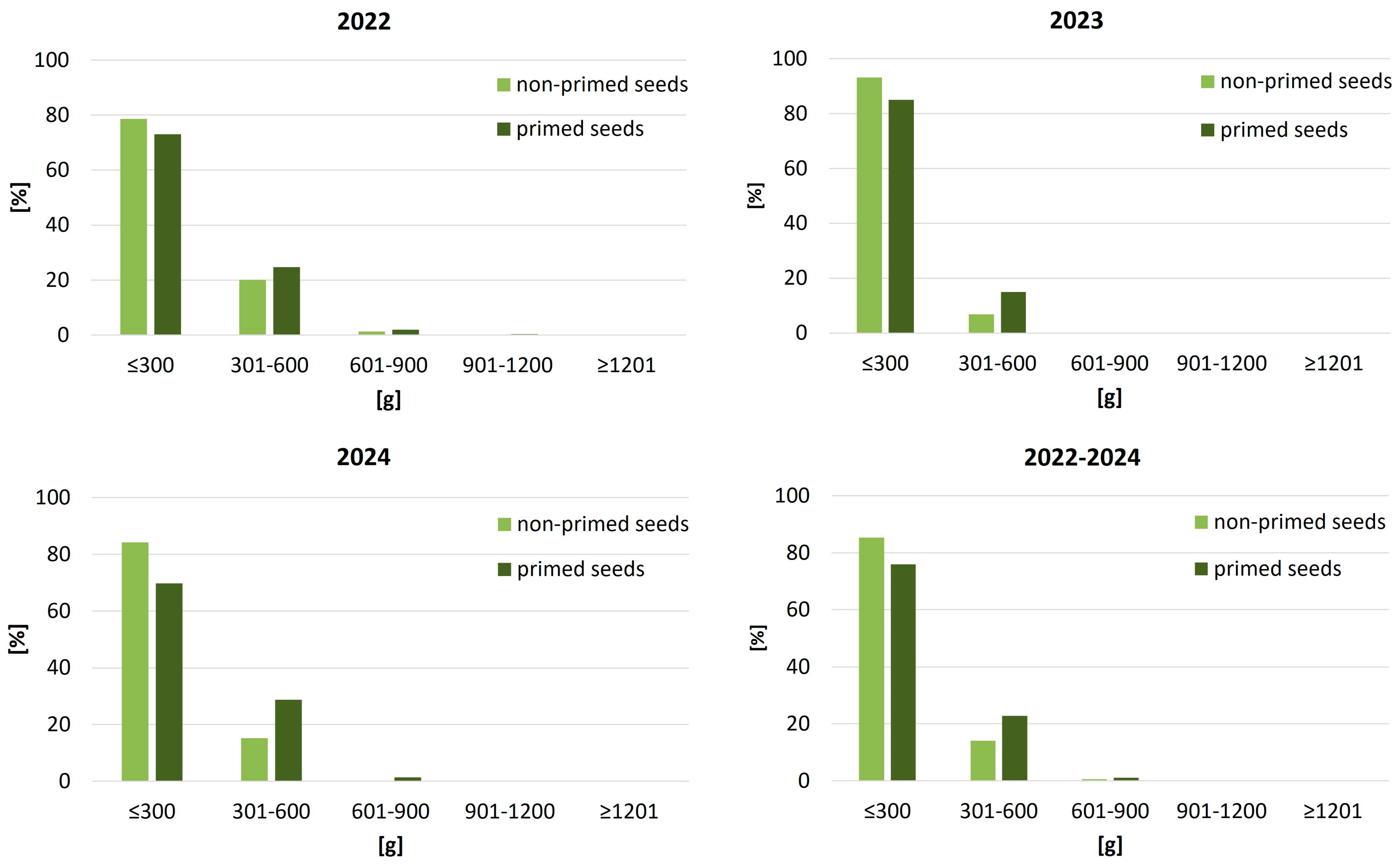

Sugar beet seed emergence dynamics varied noticeably across the three years (2022–2024), demonstrating a consistent improvement associated with seed priming (

Figure 1). In 2022, nearly 90% of seeds in both treatment groups emerged rapidly within 7–9 days after sowing, with only marginal emergence observed beyond this period. In contrast, unfavorable weather in 2023 significantly delayed emergence. During the first nine days after sowing, only 18.5% of non-primed seeds and 2.6% of primed seeds had emerged, reflecting the slow initial phase under cool and wet conditions. Most seedlings appeared between days 10–12, while in the primed variant, emergence extended through days 13–15 (24.0%). In 2024, emergence was more evenly distributed over time. Among non-primed seeds, 44.5% emerged within 7–9 days, whereas primed seeds showed a distinct emergence peak between days 10 and 12 (71.5%), followed by an additional 19.0% within the next three days. When averaged across the three years, primed seeds exhibited a more synchronized emergence pattern, with 49.9% of seedlings emerging within a narrow 10–12-day window, compared with 43.0% for non-primed seeds. This indicates that seed priming improved emergence uniformity and contributed to more stable crop establishment under variable environmental conditions.

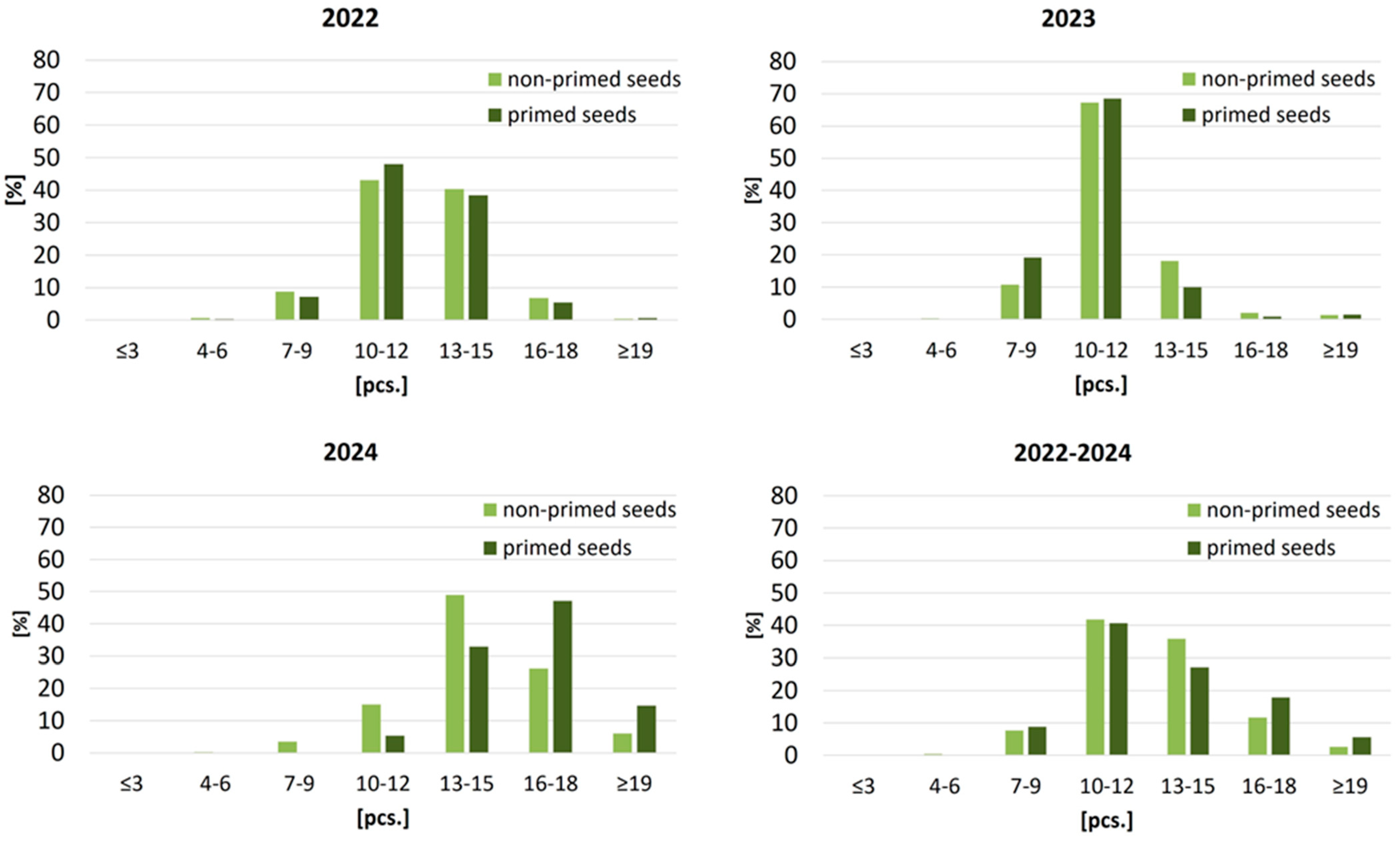

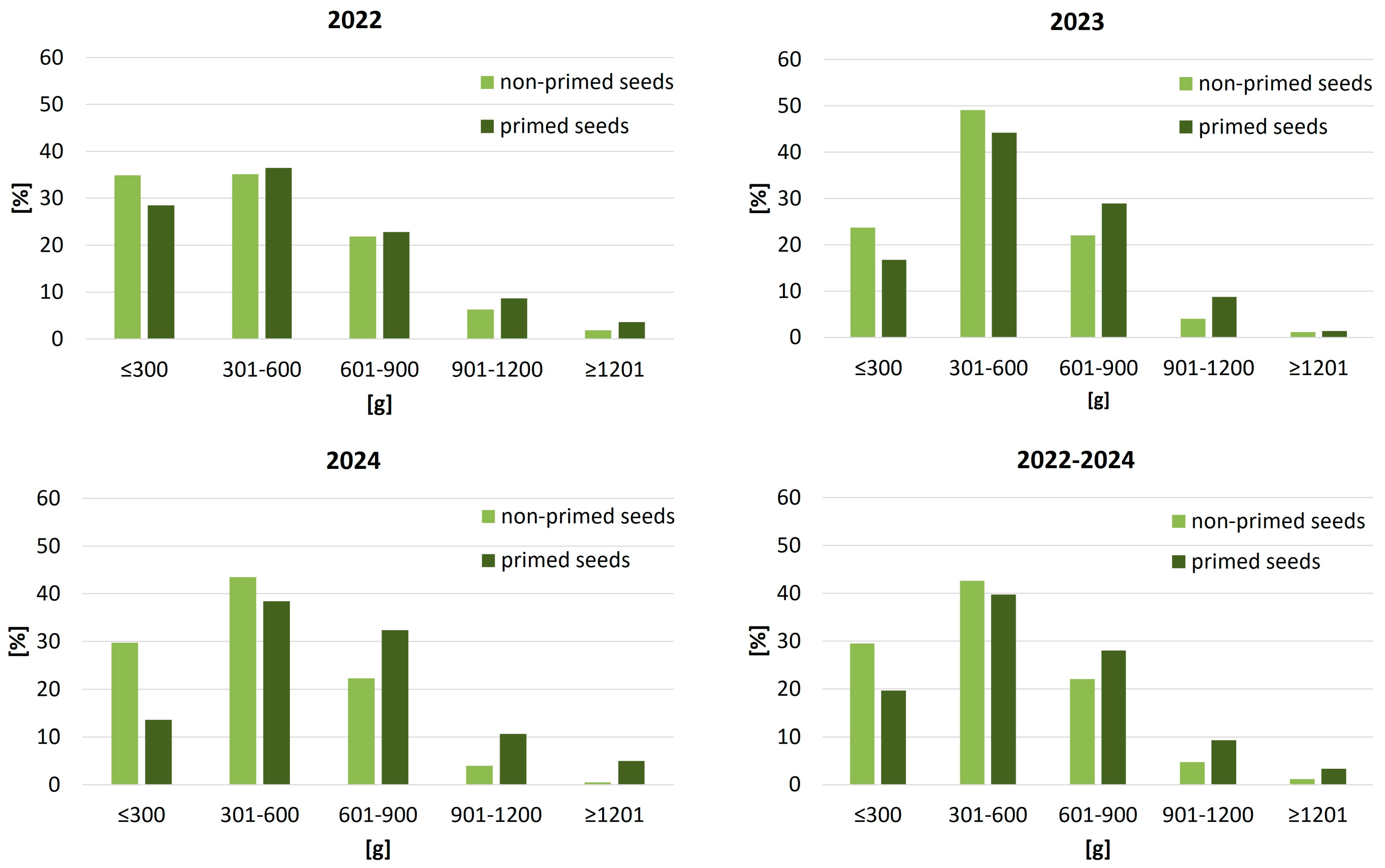

Leaf development during the 50-day juvenile stage also varied across years and was consistently improved following seed priming (

Figure 2). In 2022, most sugar beet plants developed between 10 and 15 leaves, but a higher proportion of those from primed seeds fell into the 10–12 leaf range (48.0% vs. 43.0%), indicating slightly more synchronized early growth. Under the cooler conditions of 2023, leaf counts were more tightly clustered, with over two-thirds of plants in both treatments producing 10–12 leaves. Still, the distribution remained narrower in the primed group. In 2024, favorable environmental conditions promoted extensive canopy development. Among sugar beet plants derived from primed seeds, nearly half (47.1%) developed 16–18 leaves, and 14.6% exceeded 19 leaves, more than double the share in the non-primed group. When averaged across all seasons, plants from primed seeds developed slightly more leaves and did so with greater consistency, underscoring the role of seed priming in enhancing early vegetative vigor and reducing plant-to-plant variability.

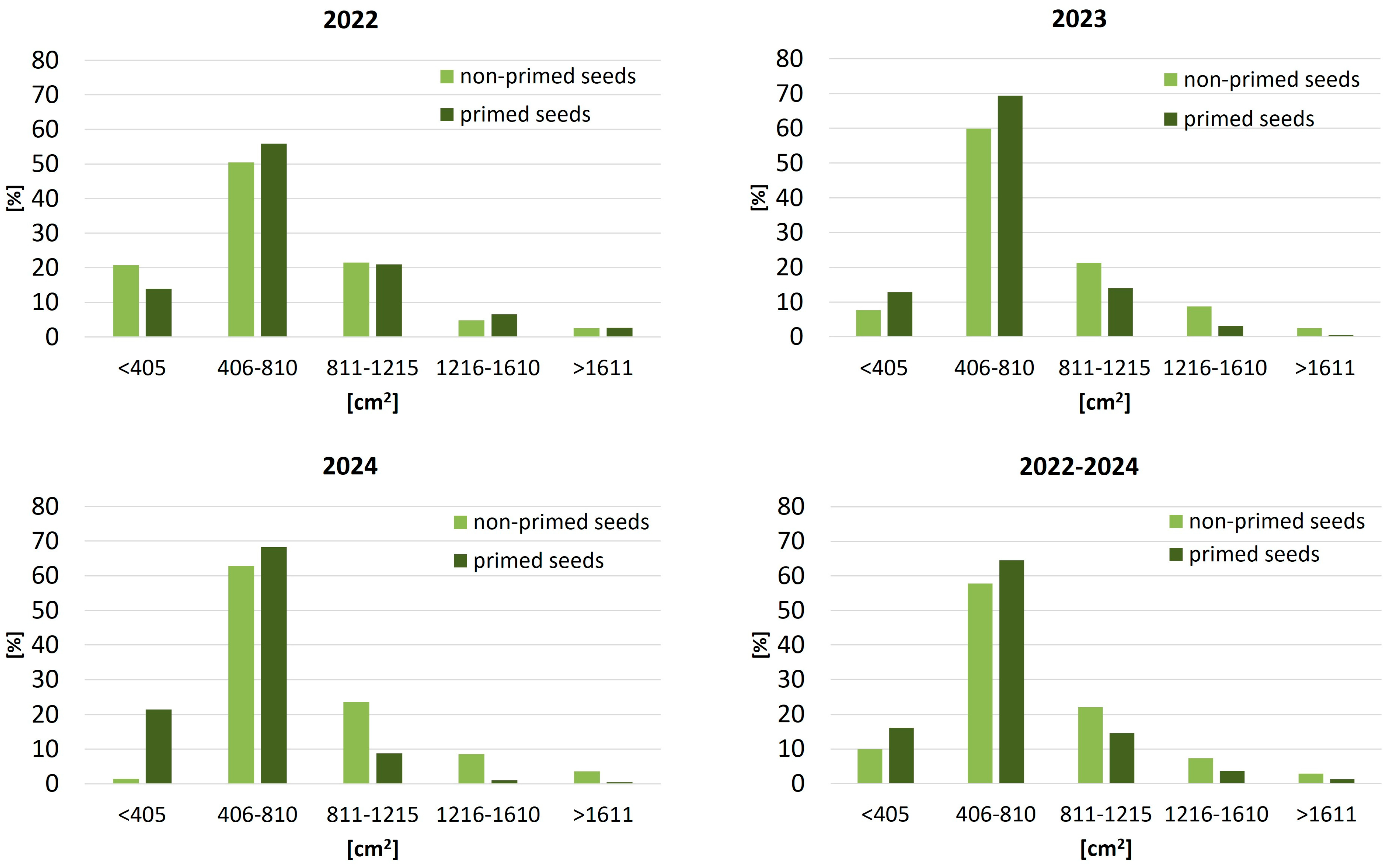

Priming treatment influenced not only emergence dynamics but also the spatial use of available growing space by sugar beet plants (

Figure 3). In 2022, just over half of the plants from non-primed seeds (50.4%) occupied the optimal living area range of 405–810 cm

2. This proportion increased to 55.9% in the primed variant, suggesting early benefits of enhanced stand establishment. In 2023, the effect became more evident: 69.4% of plants from primed seeds occupied optimal spacing, compared to 59.9% in the non-primed group. In 2024, priming again reduced the frequency of sugar beet plants with extreme spacing values (both overcrowded and widely spaced), indicating improved spatial uniformity of the canopy under varying conditions.

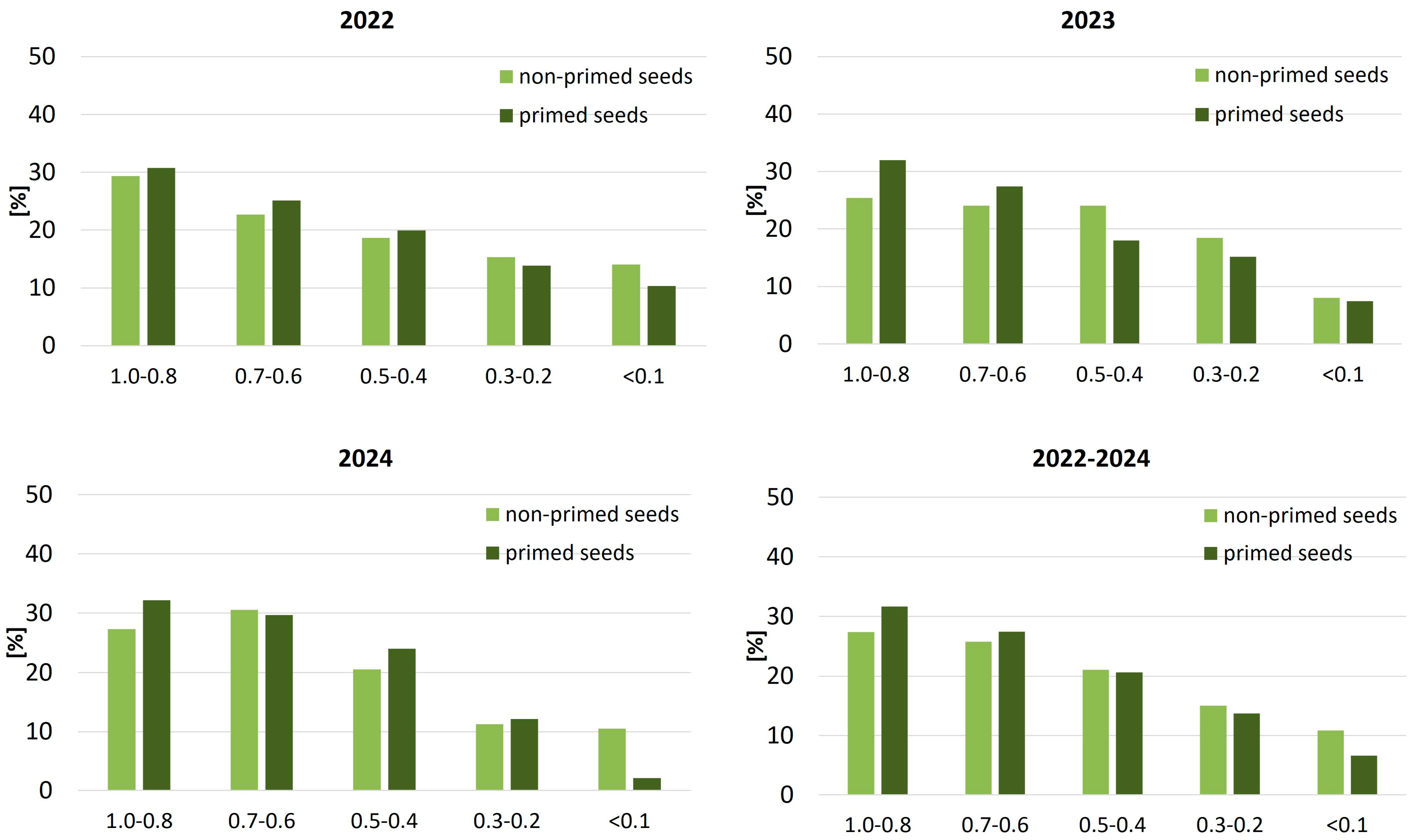

Differences between treatments were also apparent in the spatial arrangement of sugar beet plants within the row, as indicated by the location centrality coefficient (

Figure 4). A consistently higher proportion of centrally positioned plants (coefficient ≥ 0.8) was observed in the primed treatment across all seasons, most notably in 2023 (32.0% vs. 25.4%). Conversely, peripheral positioning (coefficient ≤ 0.2) occurred less frequently in the primed group, reaching a minimum of 2.1% in 2024 compared to 10.5% among non-primed plants. These patterns support the conclusion that seed priming enhances intra-row spatial regularity, which may contribute to more efficient resource capture and reduced intraspecific competition.

Sugar beet leaf biomass was consistently enhanced by seed priming across all three growing seasons (

Figure 5). In 2022, 24.7% of plants grown from primed seeds reached the 300–600 g leaf mass range, compared to just 20.1% in the non-primed treatment. This advantage became more evident under suboptimal conditions in 2023, when only 6.9% of non-primed plants exceeded 300 g of leaf biomass, while primed seeds more than doubled that share to 15.0%. In the favorable season of 2024, the effect intensified further: nearly 29% of sugar beet plants in the primed group produced over 300 g of leaves, compared to just 15.3% of non-primed plants. Notably, individuals exceeding 600 g leaf mass appeared exclusively among the primed treatment, highlighting the stimulatory impact of priming on canopy biomass accumulation.

A similar trend was observed for sugar beet root mass, which also responded positively and consistently to seed priming (

Figure 6). In 2022, the proportion of small roots (≤300 g) was reduced by 6 percentage points in the primed group (28.5% vs. 34.9%), with a corresponding increase in the higher mass classes. The differences became more pronounced in 2023, where priming significantly reduced the occurrence of undersized roots (16.7% vs. 23.7%) and substantially increased the share of plants in the 600–900 g and >900 g categories. By 2024, only 13.5% of roots from primed seeds remained in the lowest weight class, in contrast to 29.8% among non-primed, while over 5% of sugar beet roots from primed seeds surpassed 1200 g, compared to just 0.5% in the control group. Averaged across all years, the share of small roots dropped by nearly 10 percentage points with priming, and the proportion of large roots (>900 g) more than doubled.

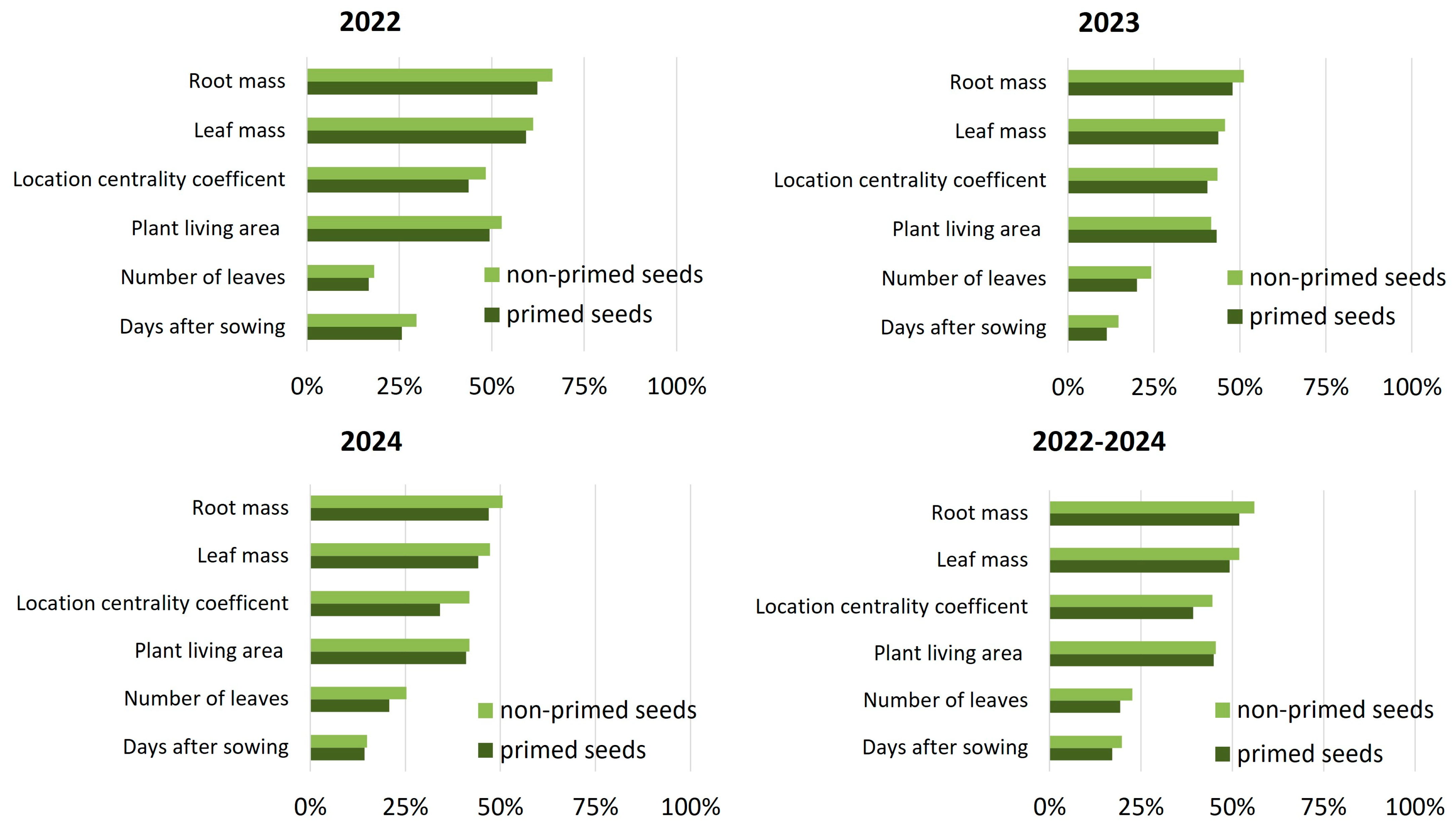

In addition to improving growth and yield, seed priming clearly contributed to greater developmental uniformity, as evidenced by lower coefficients of variation in most measured traits (

Figure 7). In 2022, variability was reduced in emergence timing (25.7% vs. 29.6%), number of leaves (16.7% vs. 18.2%), living area (49.4% vs. 52.7%), and root mass (62.4% vs. 66.4%). Similar reductions were recorded for location centrality (43.7% vs. 48.4%) and leaf biomass (59.3% vs. 61.2%). The pattern remained consistent in 2023, with lower variation for emergence, canopy traits, and root mass in the primed group, despite a slight increase in living area variability. In 2024, the stabilizing effect of priming was most visible in spatial positioning (centrality CV: 34.1% vs. 41.8%) and leaf number (20.8% vs. 25.3%). Averaged over all three seasons, sugar beet plants from primed seeds showed reduced variability in emergence, leaf count, location centrality and biomass accumulation.

Regression analysis showed that sugar beet root mass was most strongly influenced by the plant’s living area (x

3), followed by its early developmental stage during the juvenile period (x

2) (

Table 2). In contrast, the number of days to emergence (x

1) and location centrality (x

4) had weaker and more variable effects. Across all three years, plant living area consistently emerged as the strongest predictor of root mass, with significant positive regression coefficients in both seed treatments. The juvenile growth stage (x

2) also had a significant positive effect on sugar beet root mass, and this relationship was stronger for plants grown from primed seeds, suggesting that priming enhanced the contribution of early vegetative vigor to final root yield potential. Interestingly, the effect of emergence timing (x

1) differed between treatments. In the non-primed group, delayed emergence negatively affected root mass, whereas in the group grown from primed seeds, the effect was positive, indicating that priming may buffer or compensate for later emergence through mechanisms of compensatory growth. The influence of location centrality (x

4) was statistically significant but relatively modest in both groups. In the combined dataset, the effect was slightly stronger in the non-primed treatment, although this pattern was not consistent across years. Notably, in 2024, centrality had a negative effect among sugar beet plants grown from primed seeds, possibly reflecting changes in intra-canopy competition under specific environmental conditions. Model performance varied by year and treatment, with the highest determination coefficients (R

2) observed in 2022 and the lowest in 2024, underscoring the influence of annual environmental variability. We observed that the model fit well from treatment to treatment when all years were combined. This indicates that the studied sugar beet plant and canopy traits explained a similar proportion of root mass variation regardless of seed treatment.

Seed priming consistently and significantly increased sugar beet root yield across all three study years as shown with yield results in

Table 3. Yield gains ranged from 6.2% in 2024 to 7.7% in 2023, with an overall three-year average increase of 7.1% compared to the non-primed control. Final plant density remained statistically similar between treatments, confirming that the yield advantage resulted from enhanced root development in plants grown from primed seeds. The average mass of individual roots was also significantly higher in this group across all years (by 5.7–8.2%).

Despite the increased sugar beet root yield, sucrose content remained stable across treatments, with year-to-year variation from 15.8% to 17.7% and no significant differences between primed and non-primed variants (

Table 4). The three-year mean showed a slight, non-significant reduction in sucrose content in the primed treatment (16.9% vs. 17.2%). In addition to maintaining sugar content, priming also improved juice purity indicators. Reductions in sodium, potassium, and α-amino nitrogen contents were particularly marked in 2024, reaching 19.5%, 10.1%, and 16.5%, respectively. Mean reductions across years were 7.4% (Na

+), 3.8% (K

+), and 3.2% (α-amino N).

Consequently, both biological and technological sugar yields were significantly higher in the primed treatment (

Table 5). Biological sugar yield increased by 6.5% in 2022, 5.8% in 2023, and 4.8% in 2024, resulting in a three-year average improvement of 5.9%. Similarly, technological sugar yield rose from 11.5 to 12.2 t·ha

−1 (6.1%), with the greatest gain observed in 2024 (7.6%). We relate these gains to a cumulative effect of greater sugar beet root mass combined with improved juice purity, emphasizing the agronomic and technological value of priming as a pre-sowing treatment.

4. Discussion

The results of this field experiment clearly demonstrate that seed priming has a beneficial impact on multiple aspects of sugar beet development under variable field conditions. Across three years with contrasting weather, sugar beet plants grown from primed seeds consistently showed better emergence uniformity, more vigorous early growth, improved spatial arrangement, and greater biomass accumulation. These findings reinforce earlier evidence that priming enhances seed vigor and field performance in sugar beet, especially when environmental conditions are suboptimal [

14,

18,

43].

The effect of priming on emergence was among the most pronounced outcomes in sugar beet. In each year, sugar beet plants from primed seeds emerged more rapidly or within a narrower window compared to those from non-primed seeds, resulting in lower coefficients of variation and greater stand uniformity. These results agree with previous studies showing that priming accelerates metabolic activation and supports germination in sugar beet even under cold or irregular soil conditions [

10,

13,

44]. Notably, in seasons with delayed or uneven rainfall, primed seeds established more reliably, reducing stand gaps and enhancing crop resilience [

8].

The physiological basis of these improvements can be linked to early activation of enzymatic and antioxidant systems during the priming process, which enhances membrane repair, energy metabolism, and hormonal balance in the embryo. As a result, primed seeds germinate faster and more uniformly, even when water or temperature conditions fluctuate, providing an initial advantage that extends throughout later growth stages.

Beyond emergence, the benefits of seed priming extended into the juvenile stage of sugar beet development. Fifty days after sowing, plants originating from primed seeds produced similar or slightly higher leaf numbers compared to the control, but with consistently lower variation among individuals. This likely contributed to a more balanced canopy structure, improved light interception, and more efficient resource use under conditions of intra-row competition [

45,

46]. Uniform early growth also enhances the synchrony of canopy expansion and photosynthetic activity, supporting a more efficient conversion of intercepted radiation into assimilates, which are later allocated to root storage. By minimizing developmental delays among later-emerging individuals, seed priming enhanced crop synchronization, a key advantage for sugar beet cultivation under variable weather conditions [

47].

Beyond emergence and canopy development, seed priming may also indirectly influence plant health and stress resilience. In the present study, faster canopy closure in the primed treatment likely contributed to improved field microclimate and partial suppression of

Cercospora infection during humid periods. Enhanced antioxidant capacity and stress-related gene activation reported in primed seeds of other crops suggest that similar mechanisms could contribute to better tolerance of drought or temperature fluctuations in sugar beet. Future research should therefore address the link between priming-induced physiological changes and biotic or abiotic stress tolerance [

48,

49,

50,

51].

Plant spacing and canopy structure in sugar beet also benefited from seed priming. A larger proportion of plants grown from primed seeds occupied optimal living areas and were more centrally positioned within the row, resulting in a more uniform spatial distribution that reduces competition and enhances canopy efficiency [

52,

53]. Similar effects have been reported in other crops, where early developmental uniformity supports improved canopy function and yield stability [

54,

55].

Regarding biomass production, sugar beet grown from primed seeds consistently outperformed the control in both root and leaf mass, while also exhibiting lower within-crop variability. This confirms that seed priming not only promotes faster early growth but also supports more predictable yield formation, a relationship emphasized in studies linking stand uniformity to improved harvest quality and stability [

47,

56].

Although not all measured parameters differed significantly between primed and non-primed seeds, the overall patterns across growing seasons clearly indicate a consistent physiological advantage of seed priming. The absence of statistical significance in some traits likely reflects the natural variability of temperate field conditions rather than a lack of treatment response. Under such conditions, the primary agronomic value of seed priming lies in enhancing stand uniformity and crop resilience, thereby contributing to greater yield stability under stress. Even when mean differences were not significant, plants from primed seeds consistently showed lower coefficients of variation and more synchronized development, demonstrating improved consistency of performance. Similar trends have been reported in sugar beet and other crops, where priming was shown to increase yield stability and reduce variability rather than to maximize absolute yield [

57,

58]. The strong correlation between early canopy traits and root mass observed in our study further indicates that the benefits of priming are cumulative, as early vigor, spatial regularity, and balanced competition interact to determine final yield potential.

Regression analysis provided further insight into yield formation in sugar beet. Among the traits tested, plant living area and early developmental stage had the strongest positive effects on root mass. In contrast, emergence timing and spatial centrality played smaller but still significant roles. Notably, the effect of emergence timing differed between treatments: in the non-primed group, delayed emergence reduced root mass, whereas in the group originating from primed seeds, this trend was reversed. This suggests that seed priming supports compensatory growth mechanisms that can mitigate the negative impact of delayed emergence on final yield [

59].

The distinct weather pattern in 2023, characterized by excessive rainfall and prolonged soil moisture, delayed field emergence and limited canopy development, partially masking the positive effects of seed priming observed in the other two seasons. Such conditions likely reduced soil aeration and slowed root growth, minimizing early vigor advantages. Nevertheless, the primed treatment still showed more stable establishment and lower within-row variability than the control, indicating that priming may enhance resilience even under adverse moisture conditions.

Importantly, seed priming helped reduce trait variability in sugar beet not only under favorable but also under more stressful conditions, such as the dry spring of 2022 and irregular rainfall in 2024, indicating that primed seeds increase crop resilience and performance stability when weather is unpredictable. Similar benefits have been reported in other crops, including maize and sunflower, where priming enhanced stress tolerance and reduced yield variation [

60,

61].

The benefits of sugar beet seed priming were also clearly reflected in root yield and technological quality. In all three years, the treatment with primed seeds resulted in significantly higher root yields, with increases ranging from 6.2% to 7.7%. These gains were primarily attributable to greater average sugar beet root mass, as final plant density remained unaffected by seed treatment. This pattern confirms more effective biomass allocation and sustained growth throughout the season, in line with earlier results that early growth uniformity enhances root yield potential in sugar beet [

46,

62]. Similar yield improvements or enhancements in stand uniformity and quality following seed priming have also been reported in sugar beet and other root or industrial crops [

31,

63,

64,

65].

Although sucrose content did not differ significantly between treatments, sugar beet roots derived from primed seeds consistently contained lower concentrations of molasses-forming substances: Na

+, K

+, and α-amino N, which improved juice purity and sugar extractability. These improvements may be related to physiological and biochemical mechanisms activated during the priming process. Controlled hydration promotes membrane repair, selective ion transport, and antioxidant enzyme activation, which collectively enhances nutrient regulation and reduces the accumulation of Na

+, K

+, and α-amino N in root tissue. Improved canopy photosynthesis and assimilate partitioning in primed sugar beet plants further contribute to higher sucrose content and lower impurity levels, resulting in better juice purity and extractable sugar yield [

66,

67].

The most pronounced effect was observed in 2024, when sodium levels were reduced by nearly 20%. Similar improvements in nutrient balance and physiological efficiency due to seed priming have been reported in other crops as well [

68,

69].

Overall, the present findings confirm that the agronomic advantages of seed priming arise from a combination of physiological mechanisms (enhanced metabolism, stress tolerance) and structural traits (uniform spacing, canopy symmetry) that collectively support yield formation and sugar quality. The consistency of these effects across contrasting seasons highlights priming as a practical, resilient, and climate-adaptive strategy for sugar beet production.

As a result, both biological and technological sugar yields were significantly higher in the primed treatment across all years of the study. Mean increases of nearly 6% for both indicators suggest that the benefits of seed priming extend well beyond early emergence and canopy development, contributing directly to processing quality and economic returns.

From a practical perspective, the Quick Beet technology evaluated in this study is already implemented in commercial sugar beet seed production and compatible with standard industrial processing systems. Its scalability has been demonstrated through integration with mechanical mixing and controlled drying units used by seed companies. Therefore, the positive field results presented here confirm not only the agronomic value of priming but also its feasibility for broad adoption in commercial seed treatment programs.

The use of one cultivar limits inference across genetic backgrounds; future work will include multi-cultivar trials to assess genotype × priming × environment interactions. Future studies should also compare different priming techniques, including hydropriming, osmopriming, and biostimulant-based methods, to identify the most effective and environmentally sustainable approaches for sugar beet seed enhancement.

From a sustainability standpoint, seed priming offers a simple and resource-efficient strategy to enhance sugar beet establishment and yield stability under variable climatic conditions. By improving emergence uniformity and reducing the need for repeated field operations, it contributes to lower input use and better resource efficiency. These advantages align with the goals of climate-smart agriculture and sustainable intensification, where stable yields are achieved through the optimization of biological processes rather than increased chemical inputs.

Because the present study focused on the field performance of freshly primed seeds, it did not address the potential effects of seed storage duration on germination or vigor. Previous studies have shown that some priming methods may shorten seed shelf life if storage conditions are not properly optimized [

12,

70]. Future research should therefore assess the longevity of primed sugar beet seeds under different storage environments to ensure their stability and viability for commercial use.

Although the present study provides clear evidence of the agronomic benefits of seed priming, its findings are limited to one location and cultivar. Expanding future research to multi-site trials and integrating economic and environmental assessments would allow a more comprehensive evaluation of the contribution of seed priming to sustainable sugar beet production systems.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that seed priming is an effective, low-cost strategy to improve sugar beet performance under field conditions. Across three growing seasons with contrasting weather, primed seeds ensured faster and more uniform emergence, enhanced canopy structure, and increased root and leaf biomass.

The reduced variability in emergence timing, juvenile development, and plant spatial arrangement indicates that priming not only improves average plant performance but also enhances stand uniformity and yield stability, particularly under stressful environmental conditions.

Beyond early growth and canopy traits, seed priming contributed to higher sugar beet root yield and improved sugar processing quality through lower concentrations of molasses-forming substances. These benefits confirm the physiological and agronomic relevance of priming as a practical tool for stabilizing yield and sugar quality in temperate regions.

Future studies should explore the effectiveness of seed priming across different sugar beet cultivars and environmental conditions, as well as assess other priming techniques to optimize responses. Given its successful use in crops such as carrot, rapeseed, and sunflower, seed priming represents a promising technology for improving early establishment, yield stability, and processing quality across a wide range of root and industrial crops.

Overall, seed priming represents a simple, reliable, and climate-adaptive strategy to enhance sugar beet emergence, canopy performance, and sugar yield under temperate field conditions.

From a practical perspective, the findings of this study suggest that seed priming can be readily adopted in commercial sugar beet seed production and on-farm practices to ensure uniform crop establishment and higher sugar yield stability. By improving emergence synchronization and canopy development, priming supports more efficient use of water and nutrients and reduces production risks under variable climatic conditions, offering a sustainable and cost-effective tool for modern sugar beet cultivation.