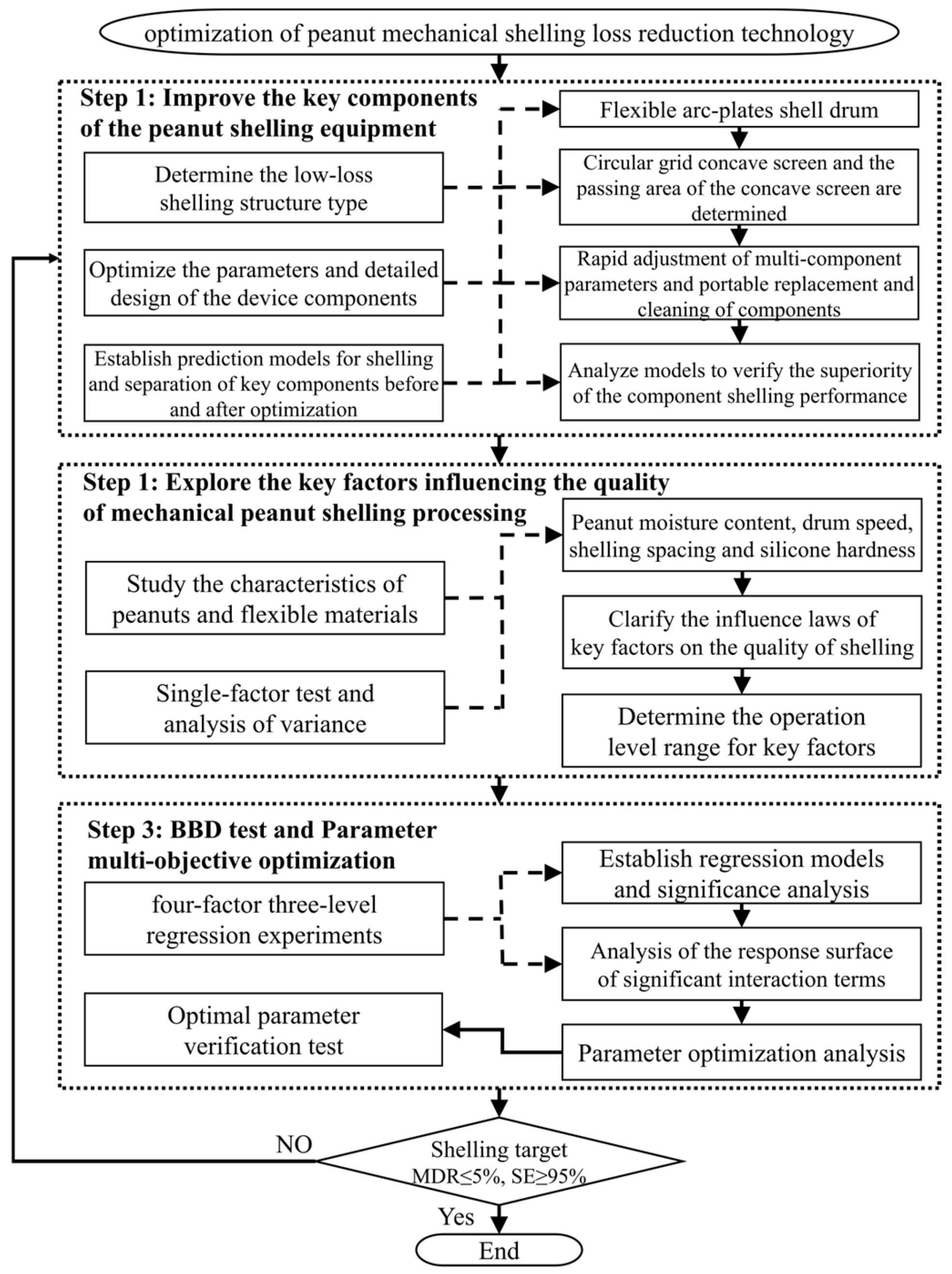

Optimization of a Low-Loss Peanut Mechanized Shelling Technology Based on Moisture Content, Flexible Materials, and Key Operating Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

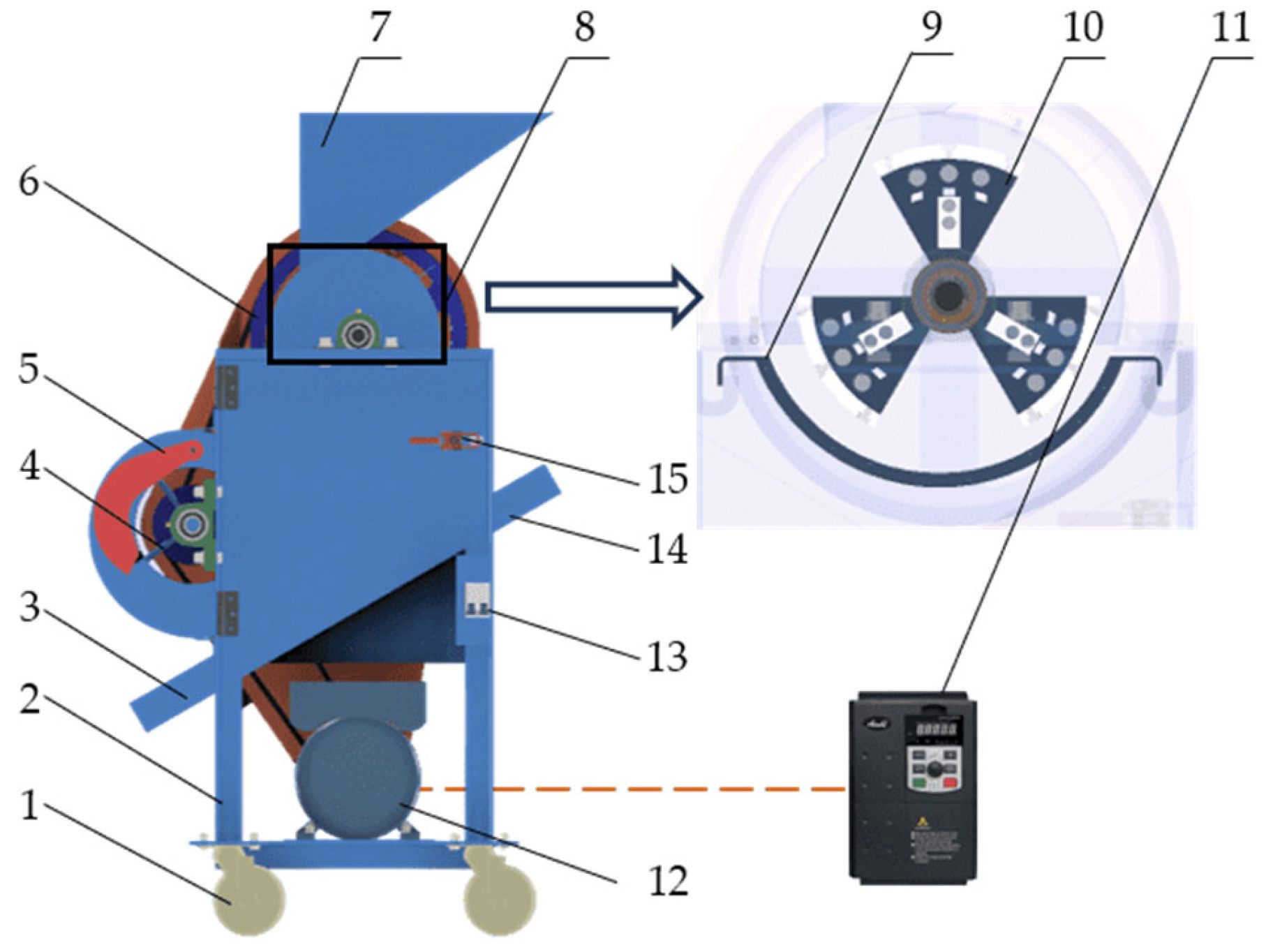

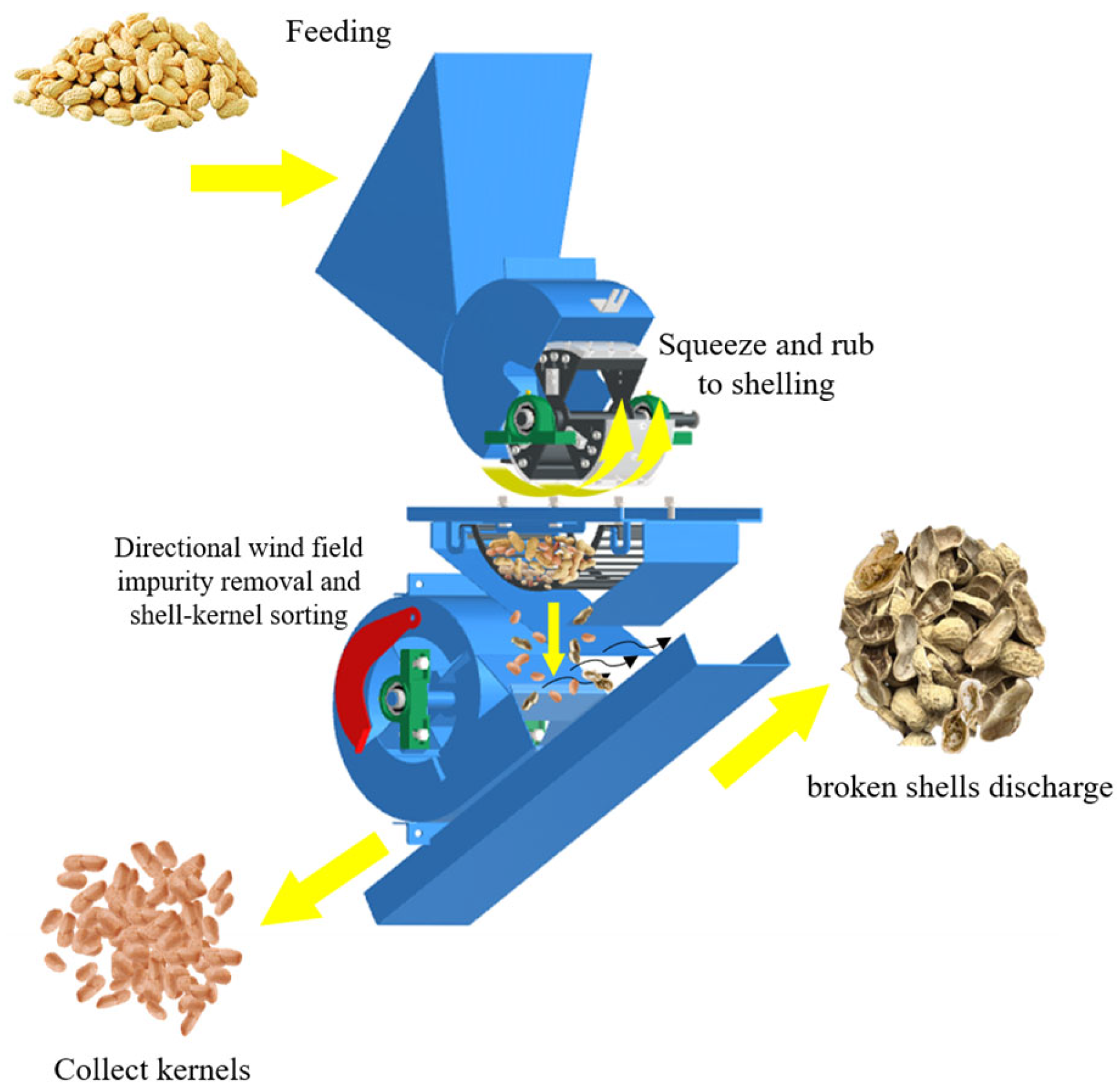

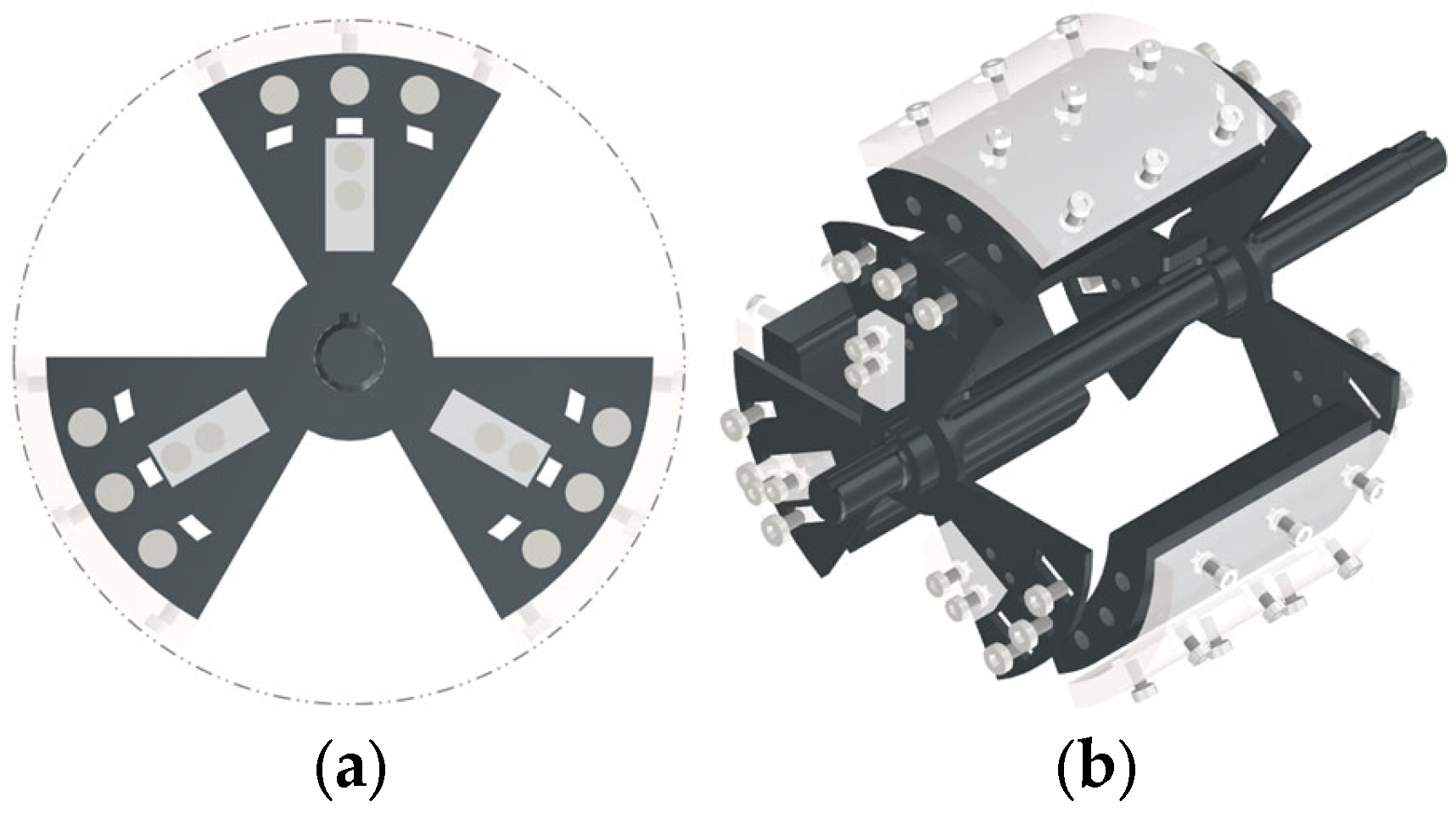

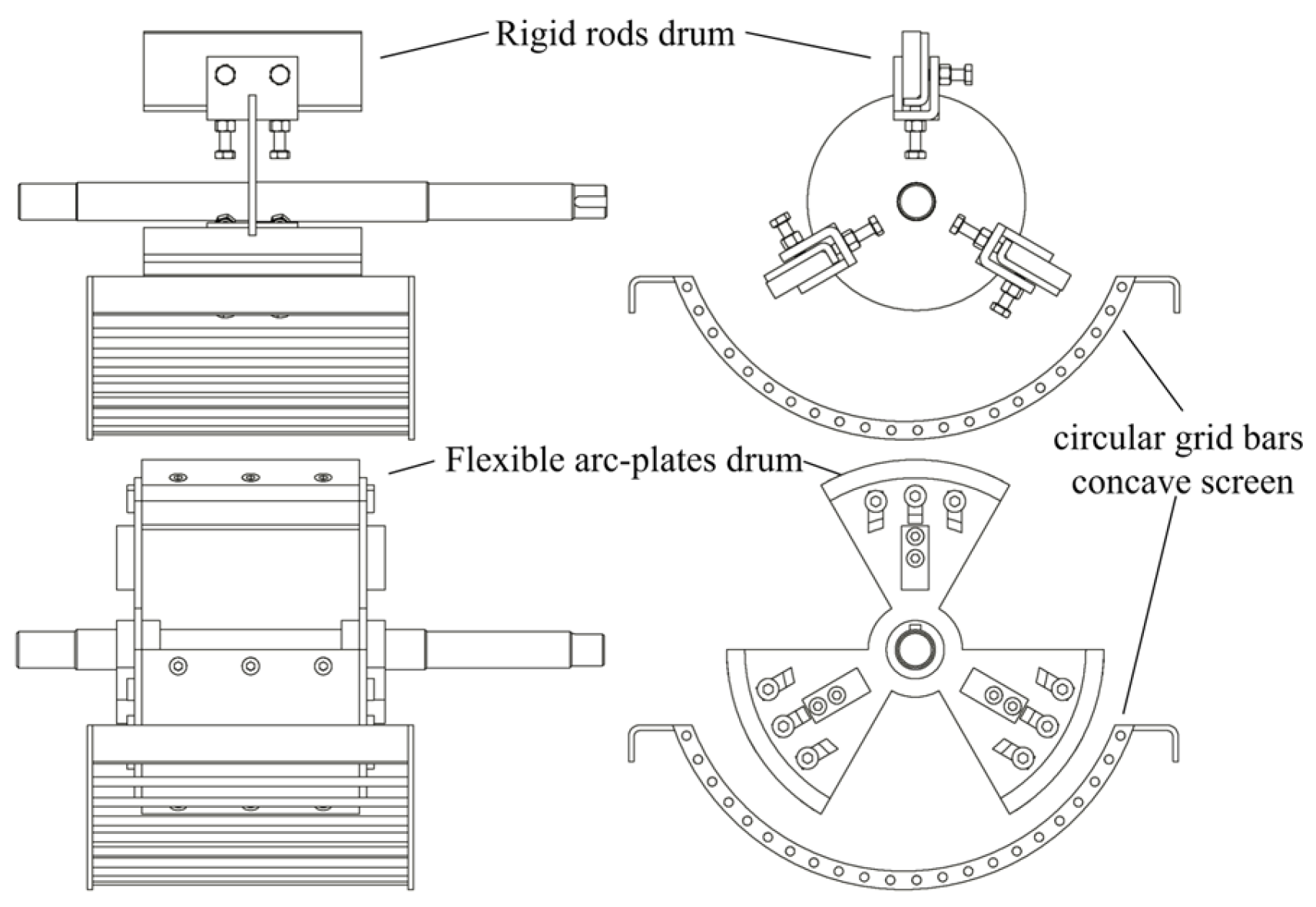

2.1. Structure and Working Principle of Peanut-Shelling Device

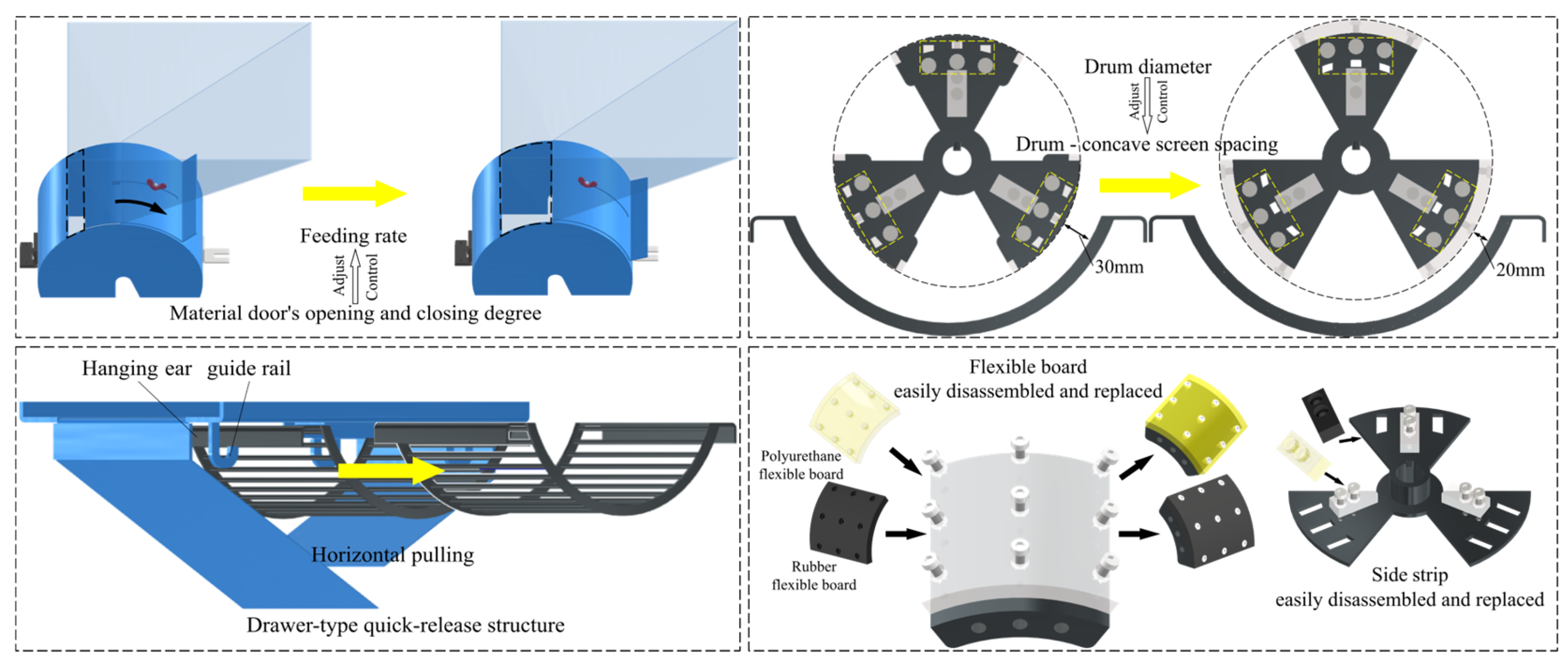

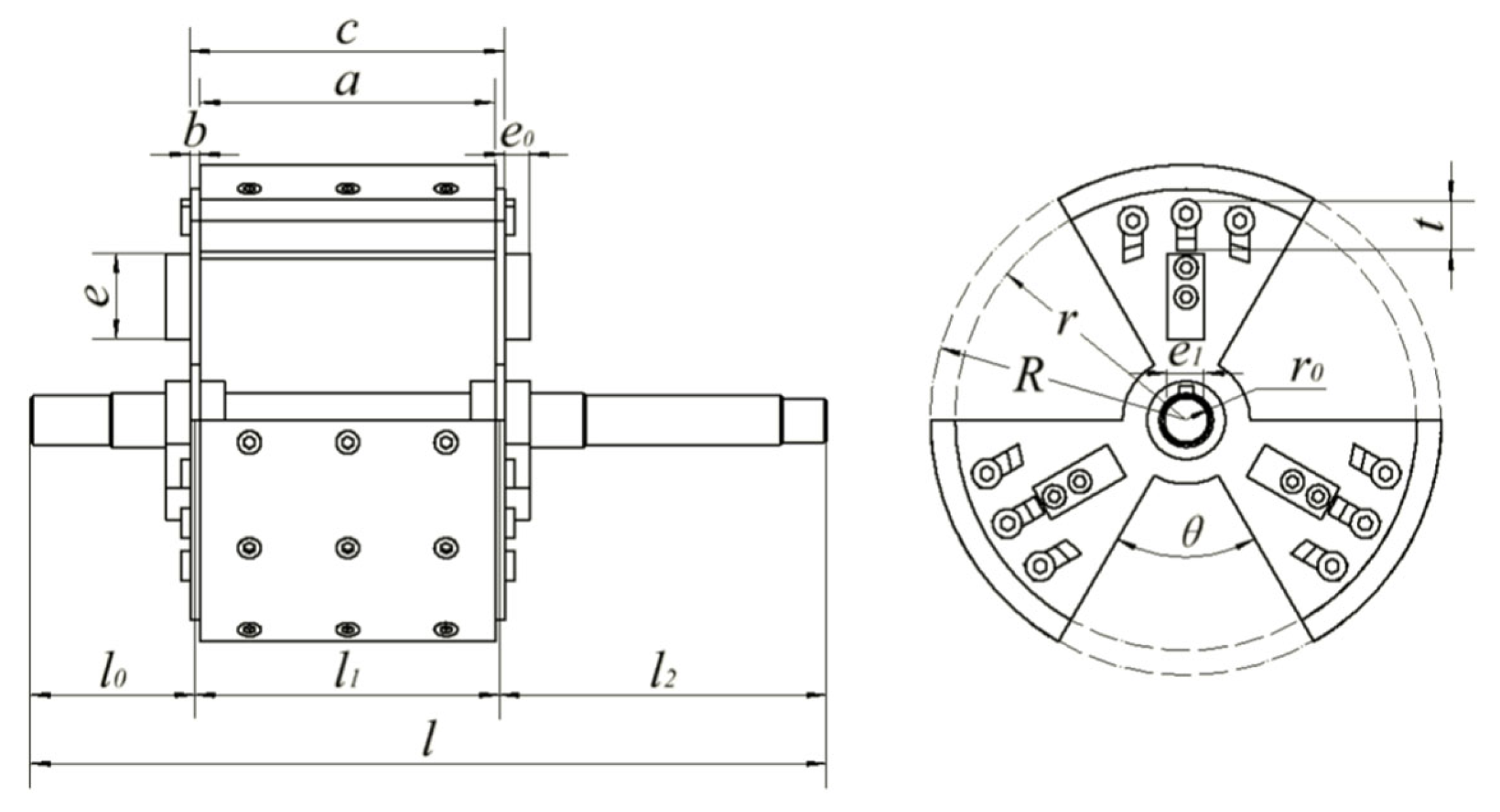

2.2. Design and Selection of Key Components for Flexible Arc-Plates Drum-Type Sheller

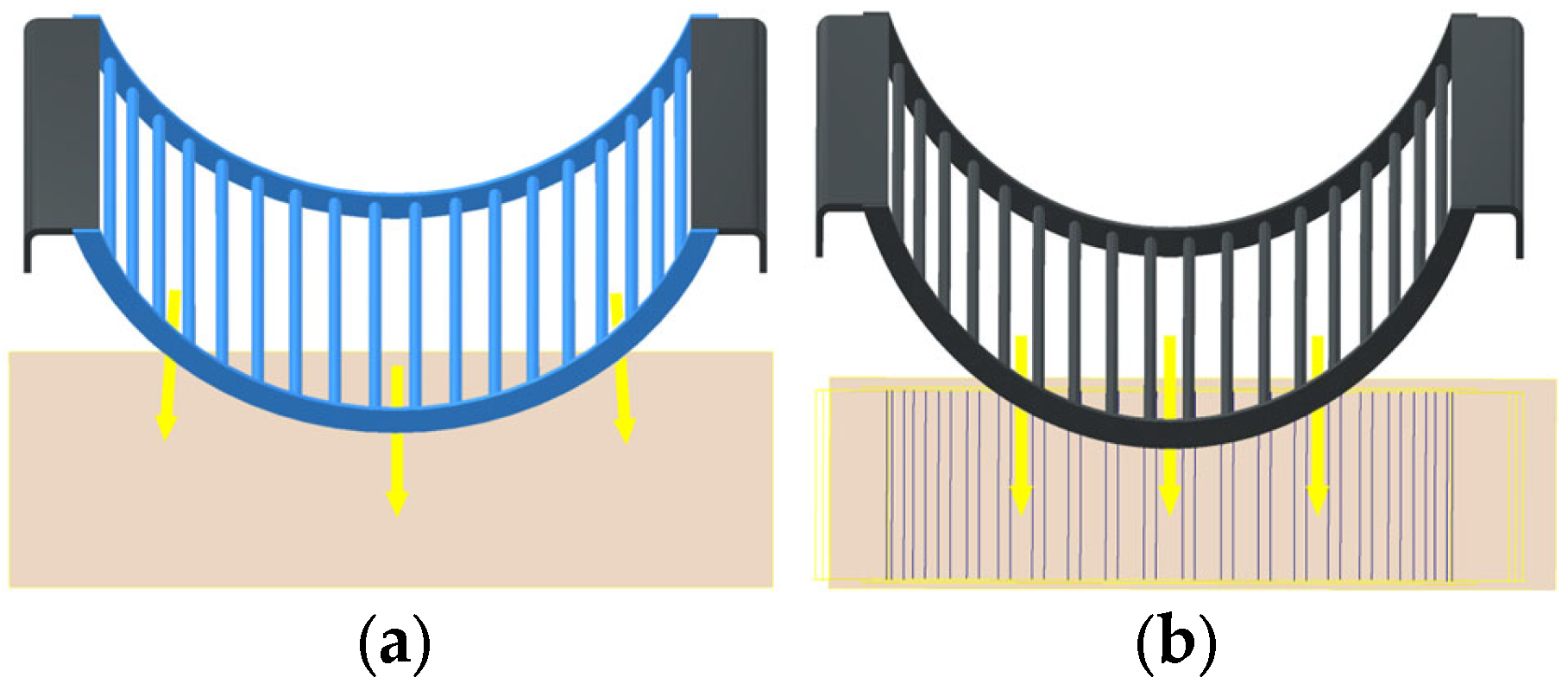

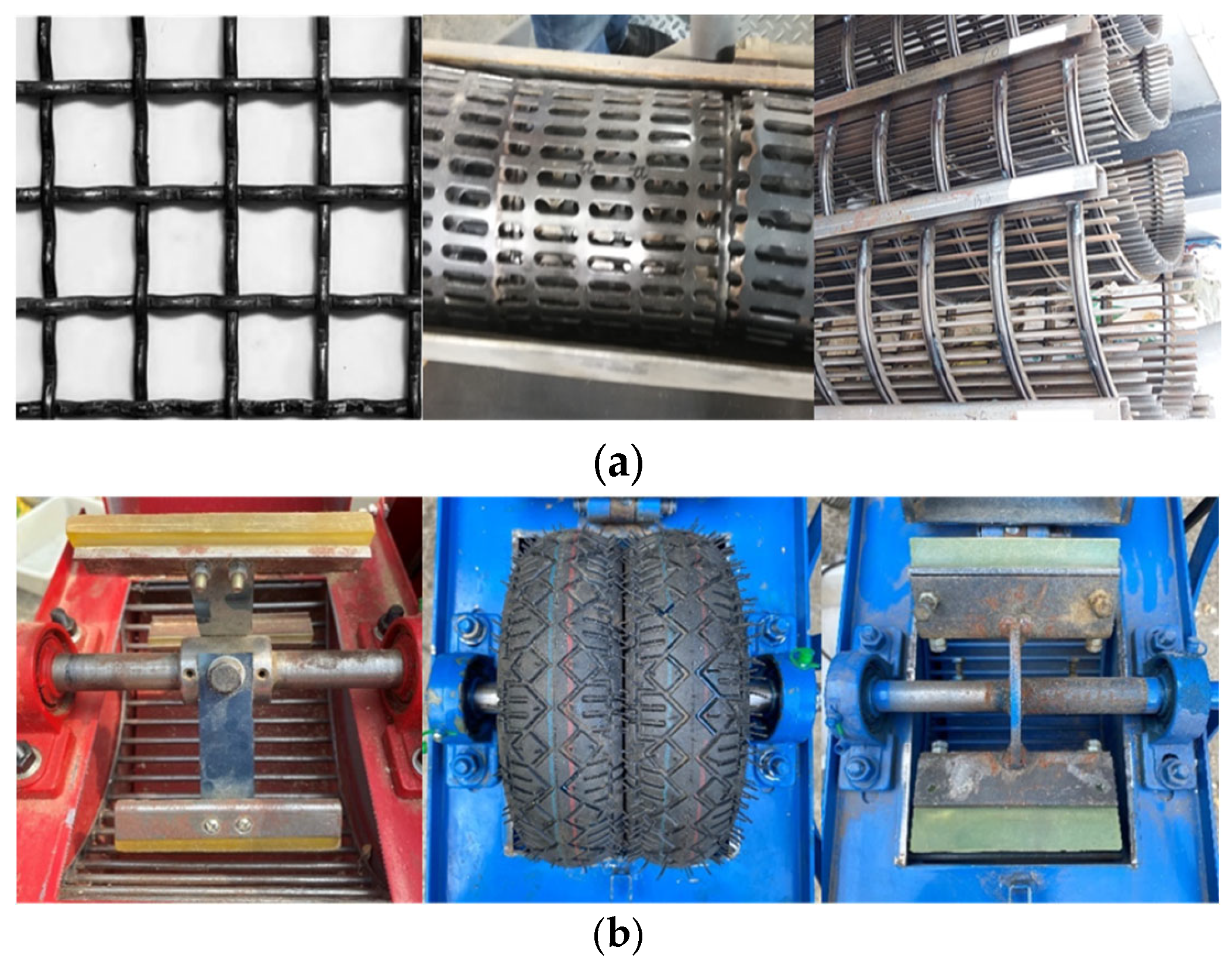

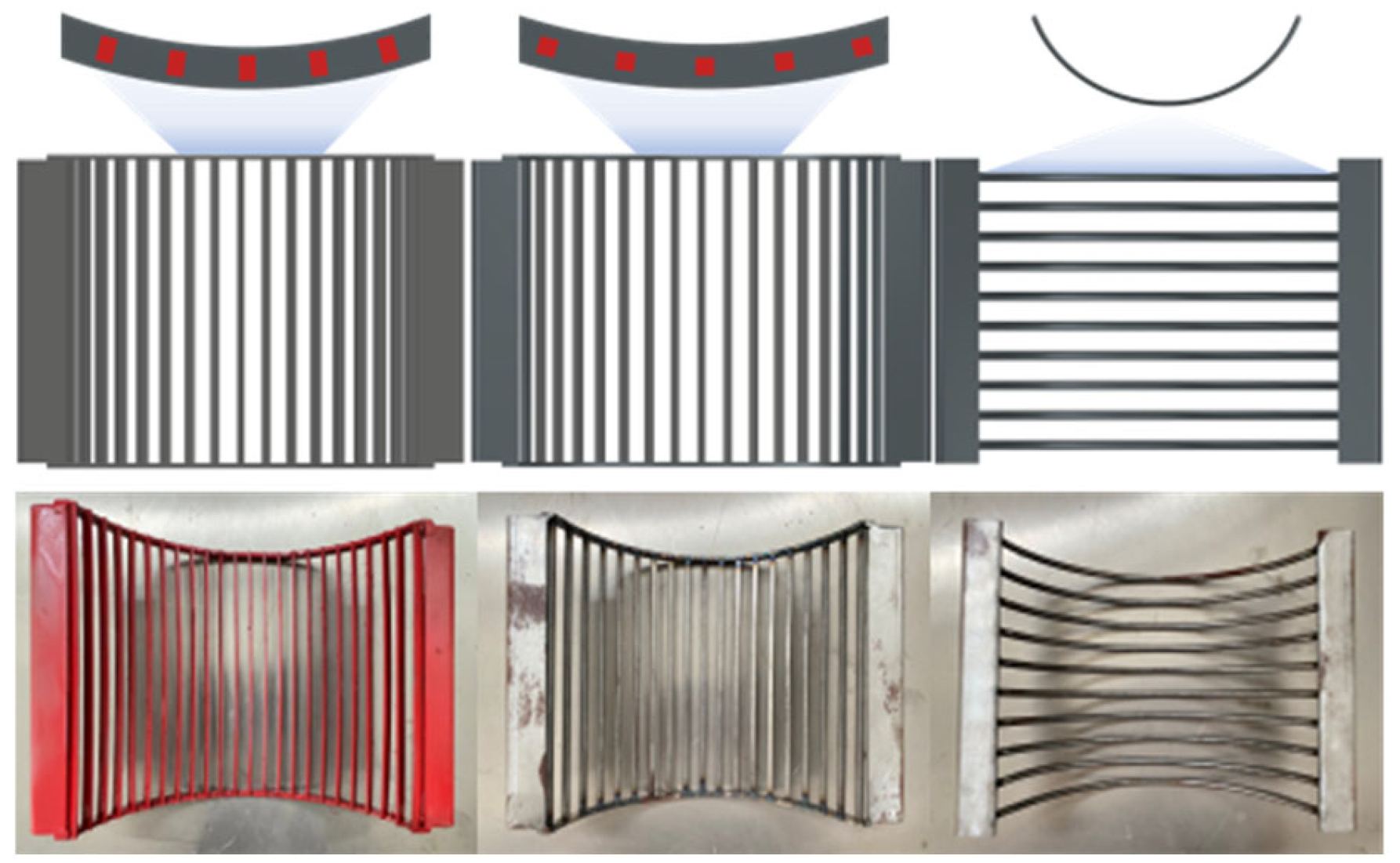

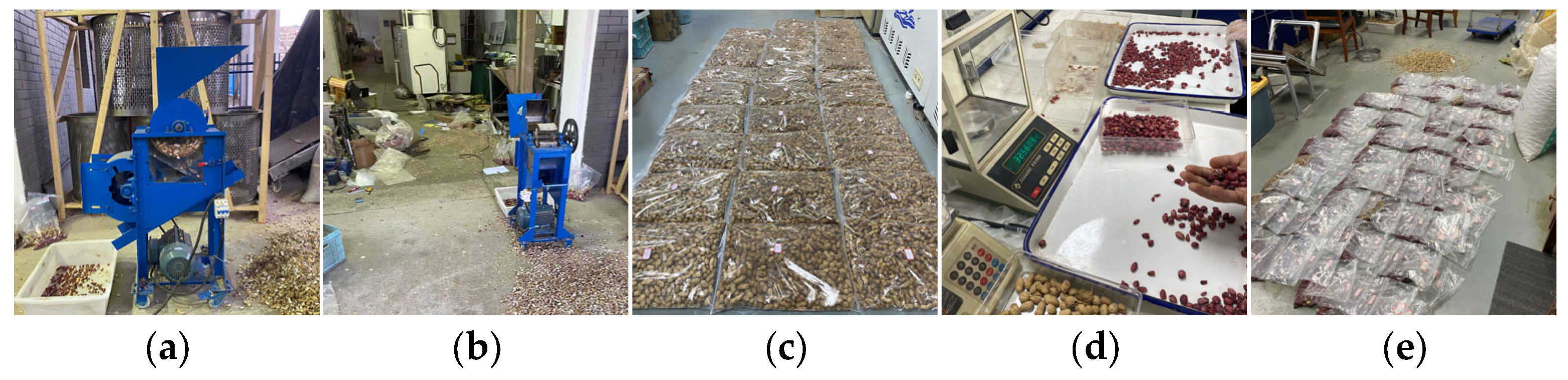

2.2.1. Selection Test for Low-Loss Shelling Structure

2.2.2. Design of Flexible Arc-Plates Shelling Drum

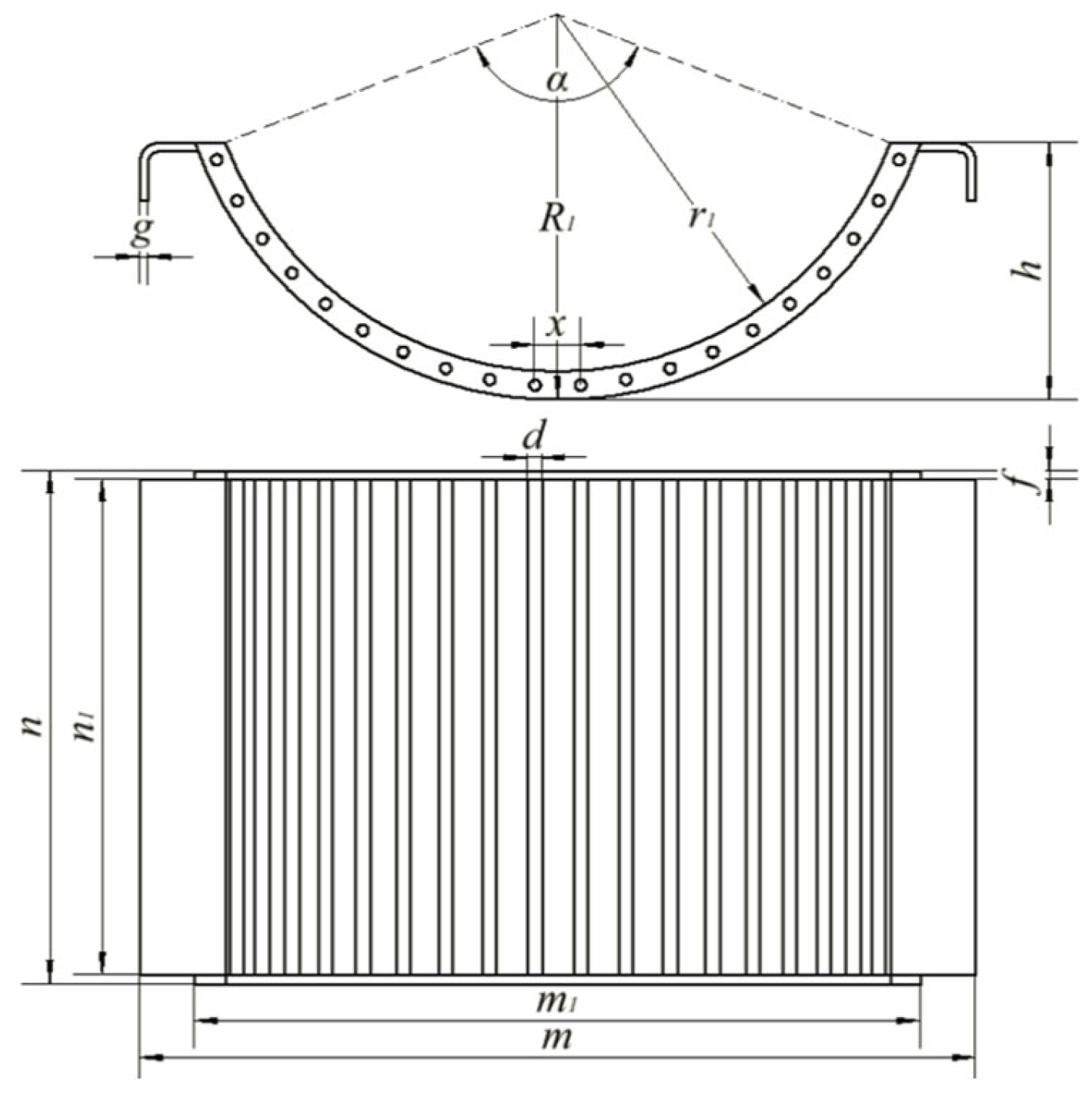

2.2.3. Design and Selection of Concave Screen

- (1)

- Design of concave screen

- (2)

- Comparative test on performance of concave screen grid bar forms

- (3)

- Determination of the passing area of the concave screen

2.2.4. Creation of Predictive Model

- (1)

- During the process of shelling and separation, the physical properties of the materials remain unchanged. The probability of pods breaking out of the shells and removing the kernels within the material pile is equal, and the probability of shell–kernel separation at any position is also equal. The peanuts are simplified into homogeneous ellipsoids, the contact area of the rods/arc-plates is simplified into regular shapes, and the gaps of the screen grid bars are evenly distributed.

- (2)

- The screen steel grid bars and the drum’s flexible materials are both regarded as isotropic linear elastomers. The plastic deformation, viscoelasticity, and strain rate effect are ignored and the material parameters are taken as the static values at room temperature. The compression deformation of the flexible material is much smaller than its thickness, and the bending deflection of the screen grid bars is less than 10% of the gap, which meets the principle of linear superposition.

- (3)

- The energy transfer during shelling is centered on a single impact by the rod or a single compression by the arc-plates, ignoring the cumulative effect of multiple repeated collisions within the drum. The elastic deformation of the screen and the flexible material is linearly superimposed through the series spring stiffness model, ignoring the friction at the contact interface and the synergistic impact effect.

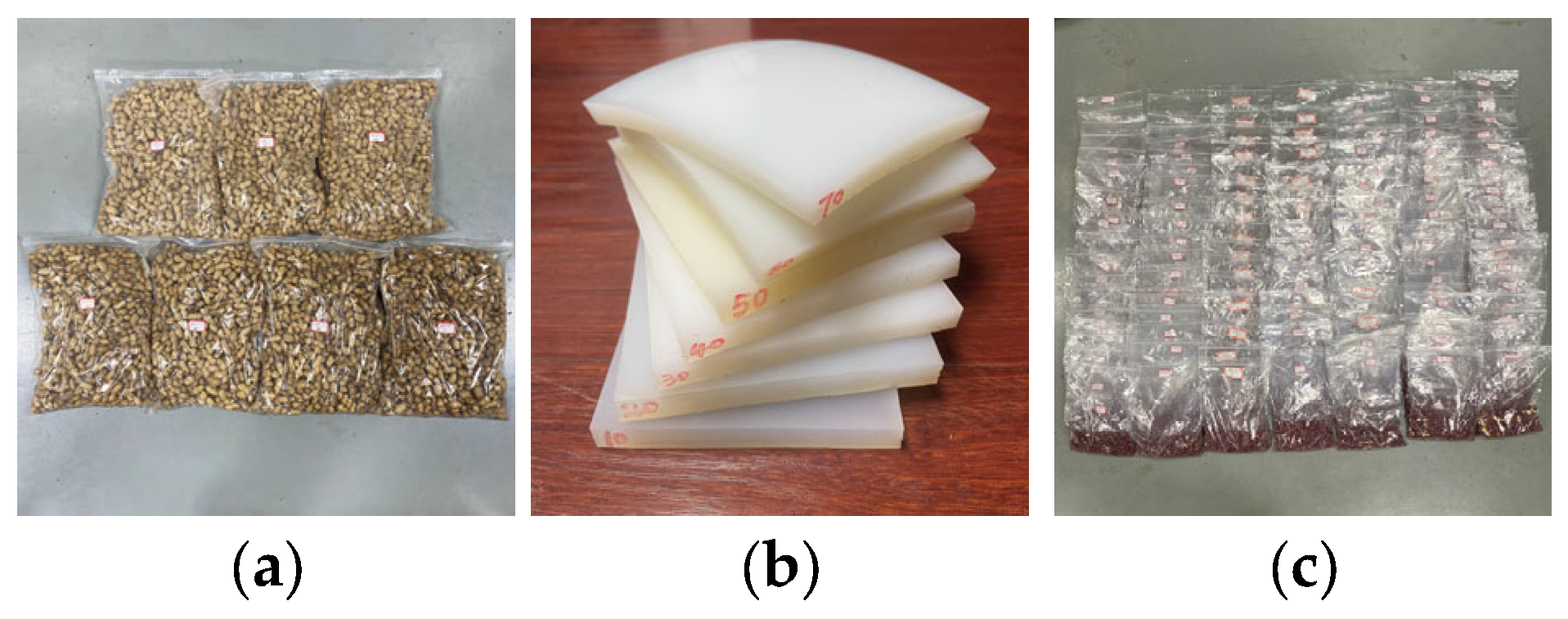

2.3. Peanut Samples and Moisture Conditioning Treatment

2.4. Experimental Indicators

2.5. Experimental Schemes

2.5.1. Single-Factor Experiment

2.5.2. Parameter Optimization Experiment Based on BBD

3. Results and Discussion

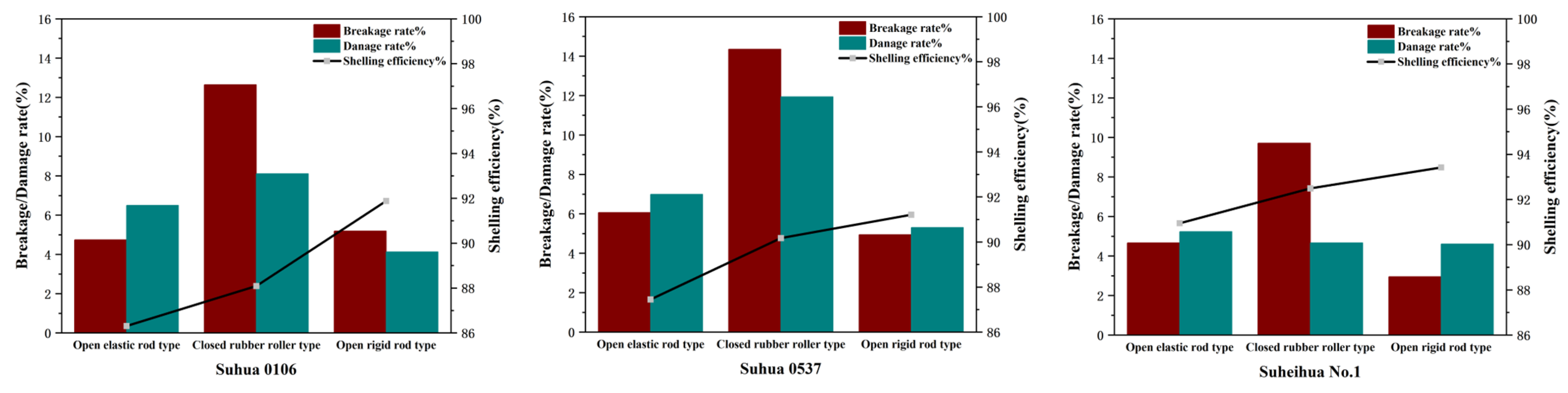

3.1. Analysis of the Test Results for the Selection of Low-Loss Shelling Structures

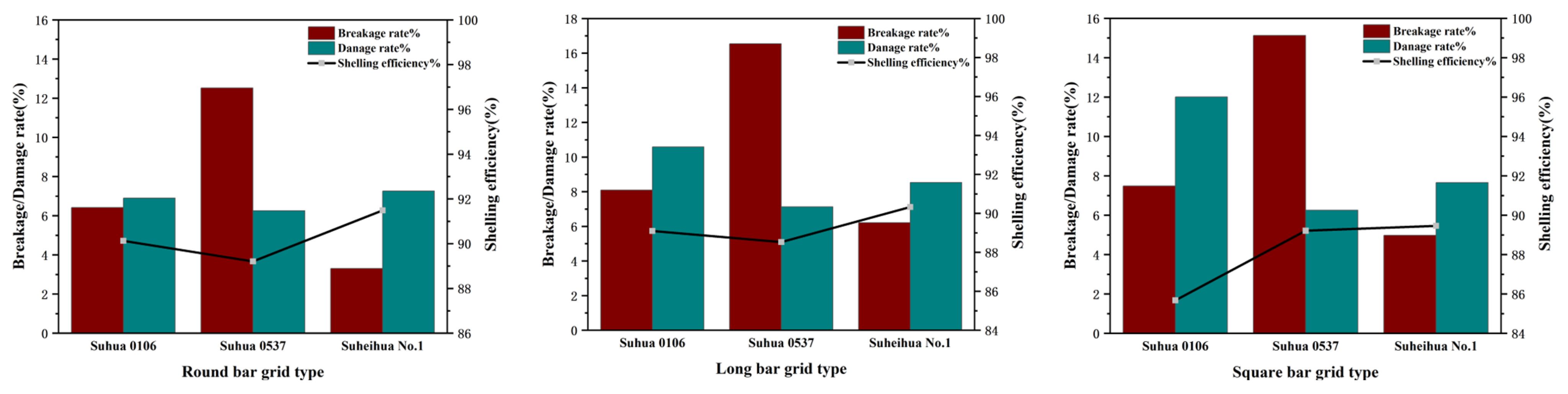

3.2. Results Analysis of the Performance Comparison Test of Concave Screen Grid Bar Forms

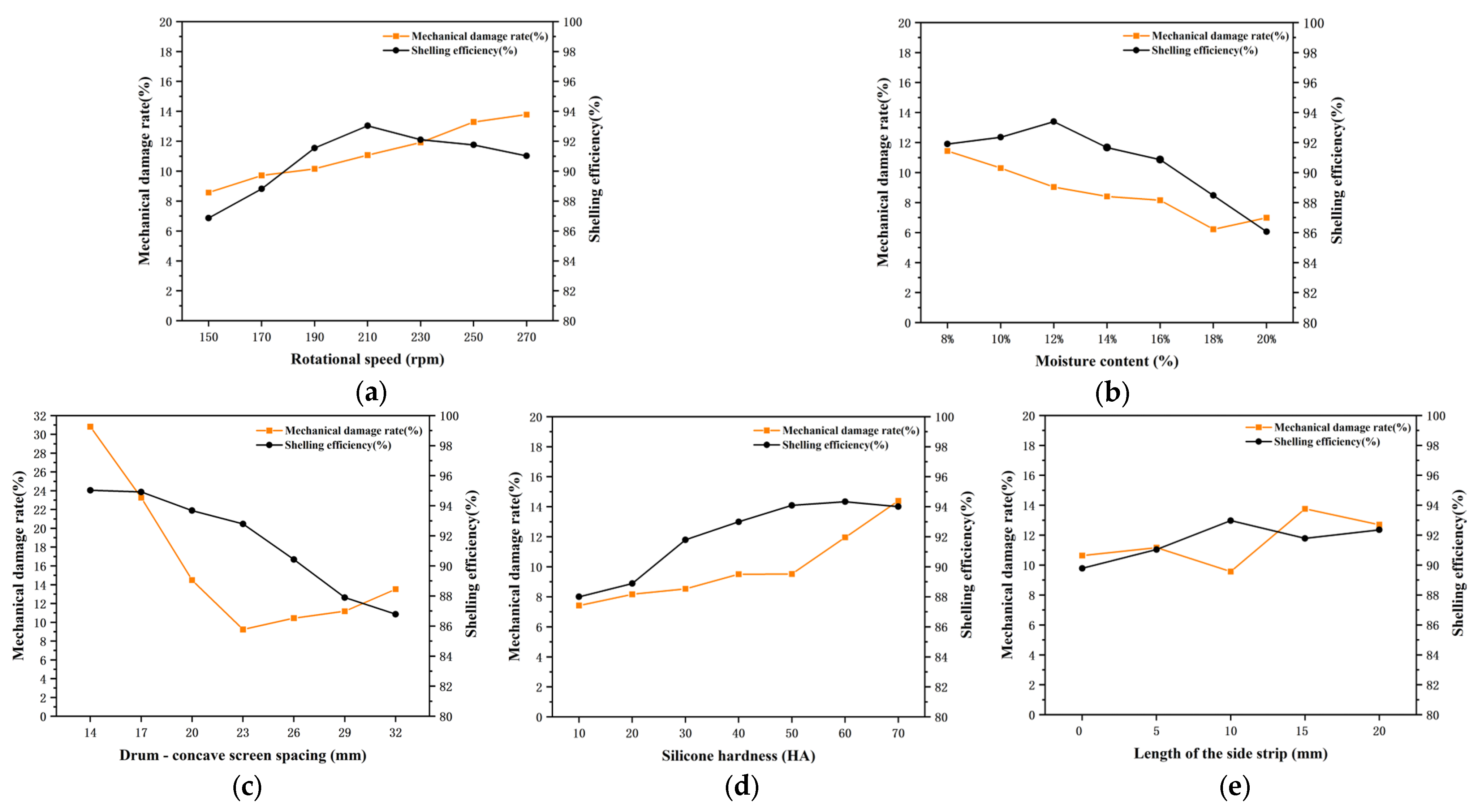

3.3. Results Analysis of the Single-Factor Experiment

3.4. Results Analysis of the Parameter Optimization Experiment

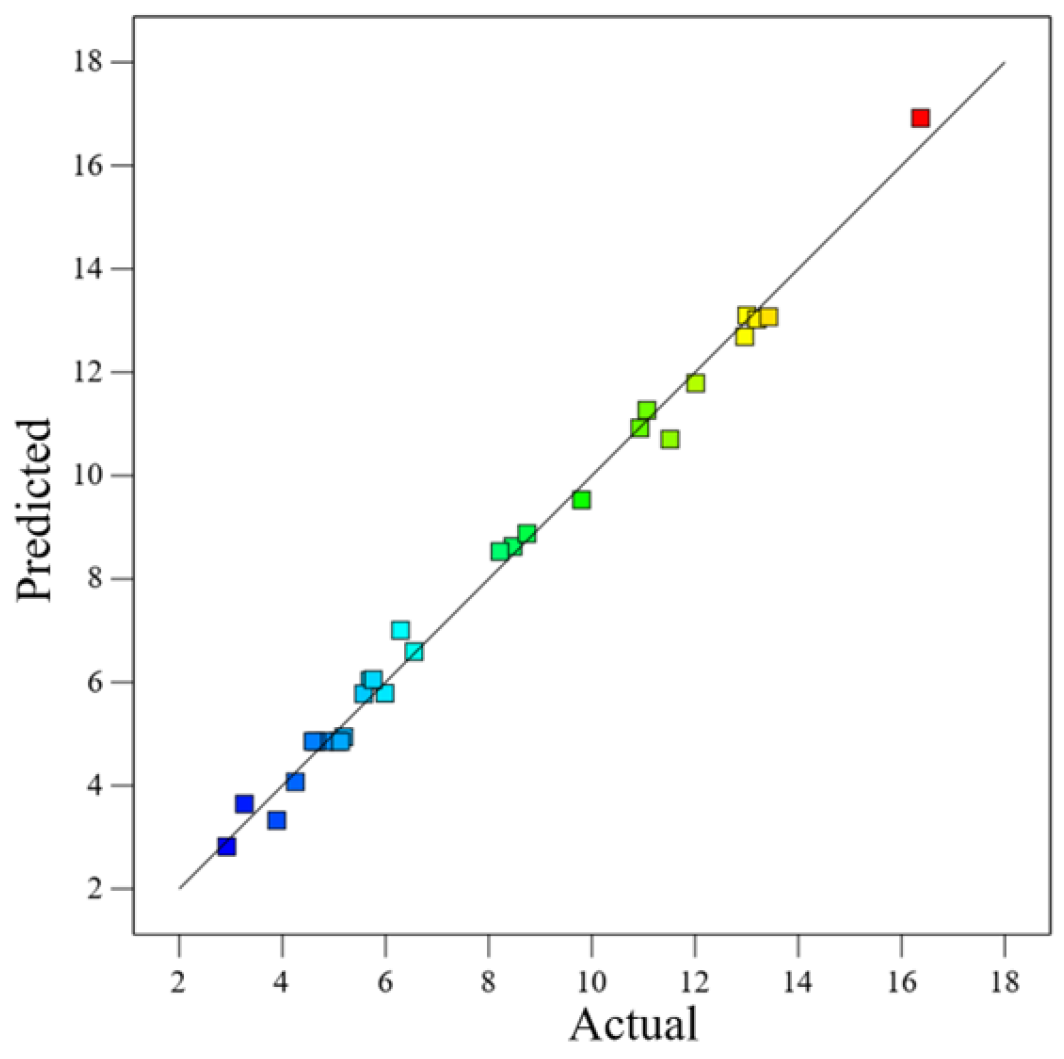

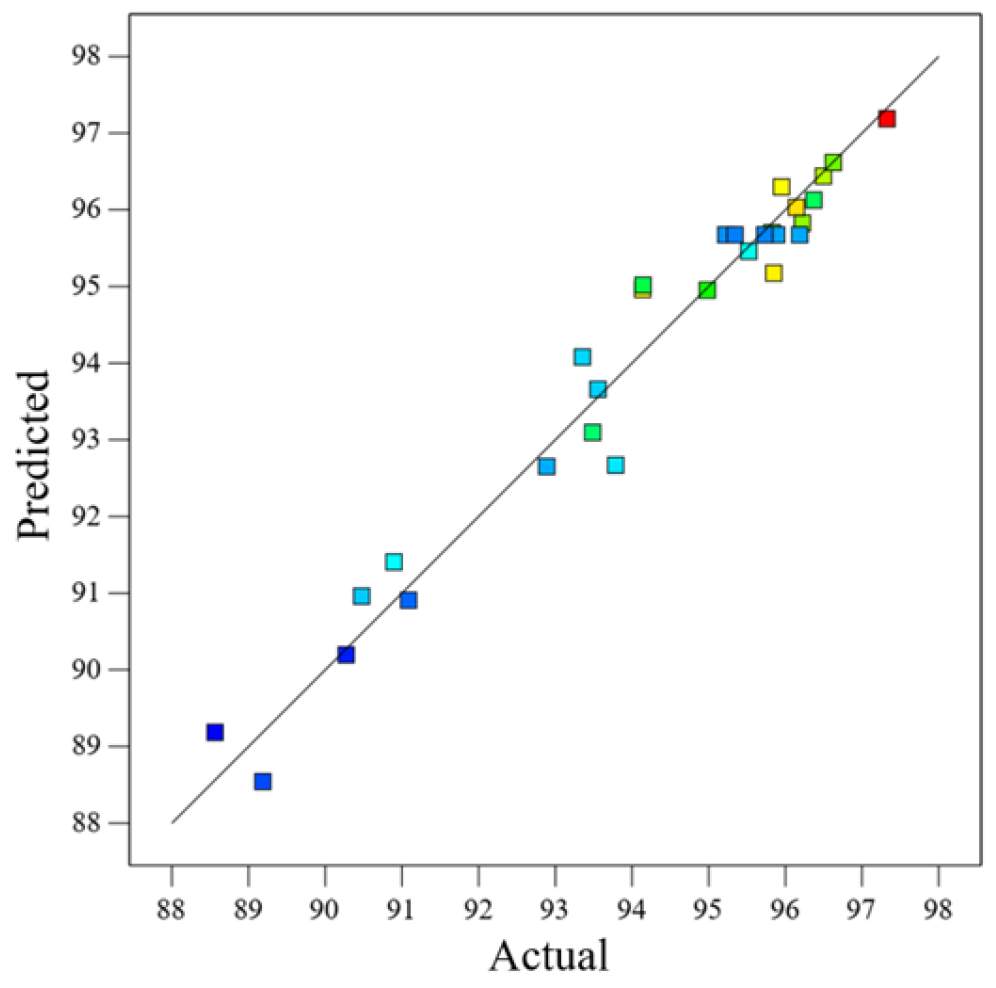

3.4.1. Regression Model and Significance Analysis

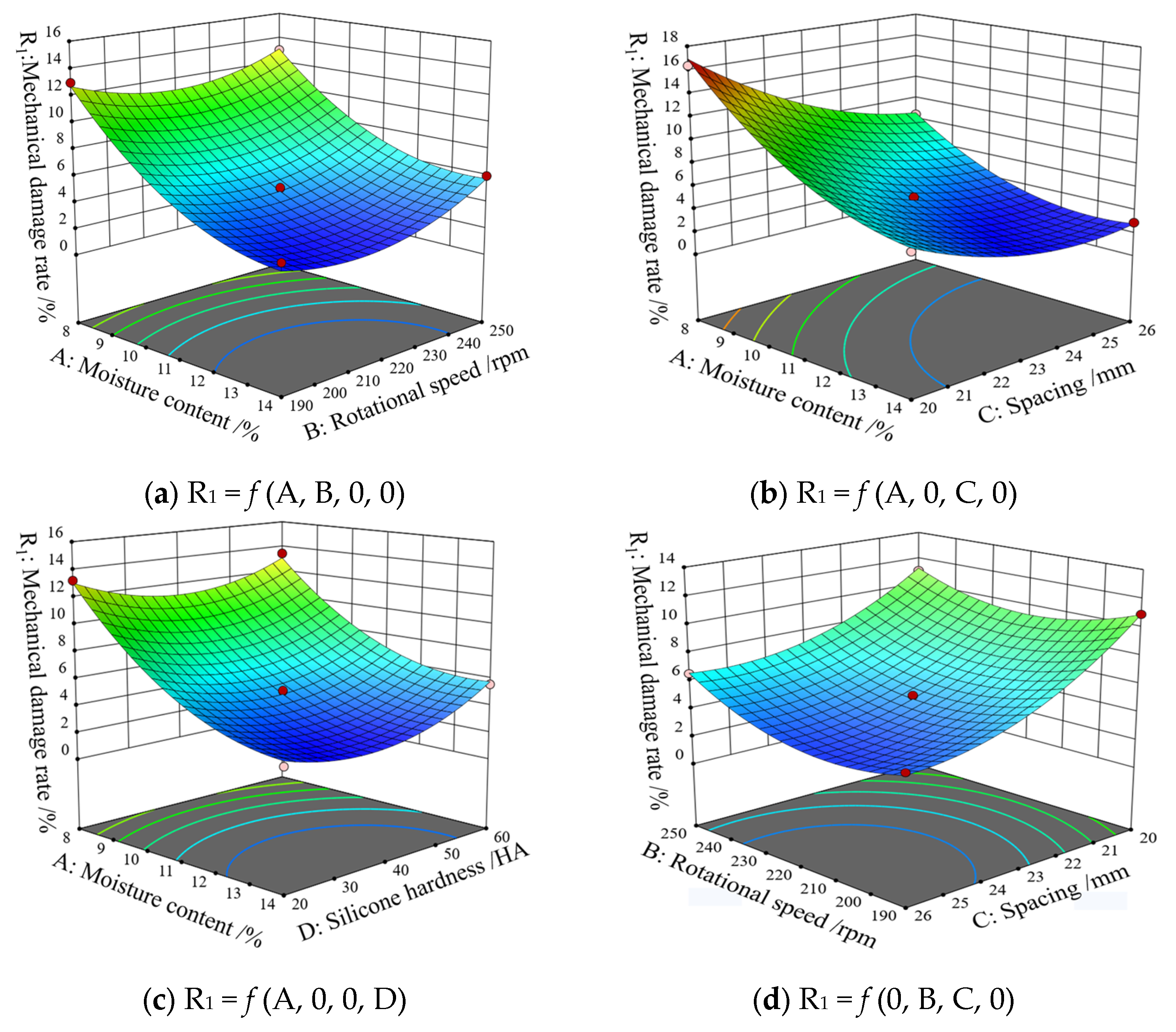

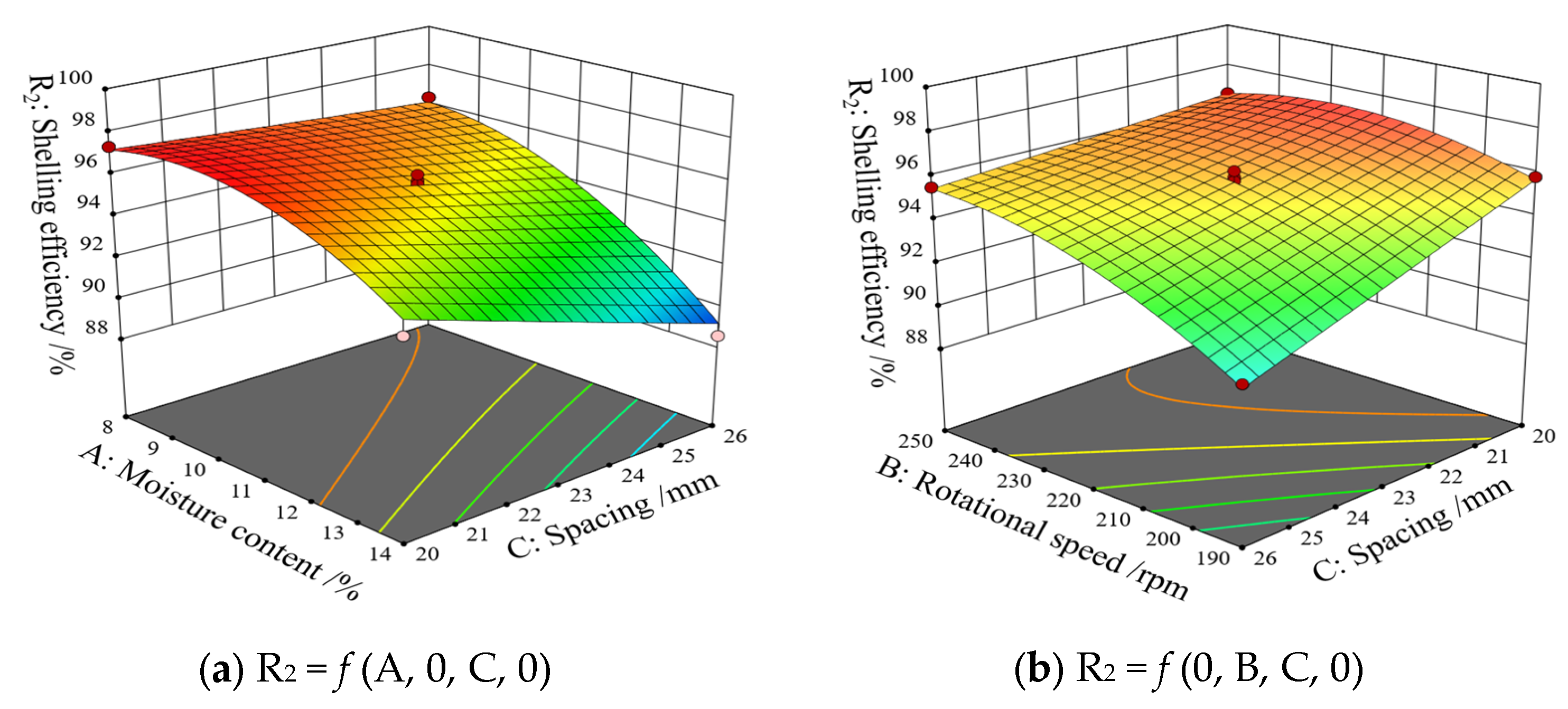

3.4.2. Response Surface Analysis and Parameter Optimization

- (1)

- Response surface analysis

- (2)

- Parameter optimization analysis

3.5. Optimal Parameter Verification Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liao, B. A review on progress and prospects of peanut industry in China. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2020, 42, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Feng, X.; Nie, J.; Peng, L.; Zang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Z. Spatio-temporal dynamics of global peanut production and trade. J. Peanut Sci. 2021, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L. Development status, existing problems and policy recommendations of peanut industry in China. China Oils Fats 2020, 45, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Bai, Z. Evolution of global peanut trade pattern and policy implication. China Oils Fats 2022, 47, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Production of Crops and Livestock Products. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data/QCL (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Lu, R.; Gao, L.; Chen, C.; Butts, C.L. Technology and characteristics of peanut shelling of United States and enlightenment. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Yue, X.; Bai, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P. Study on Aspergillus flavus infection in maize and peanut. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2022, 44, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Hui, Z.; Dong, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, H. Design and Experiment of Peanut Sheller with Three Drums for Plot Breeding. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2016, 47, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Gao, L. Performance test on double-roller peanut sheller with pneumatic circulating. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2013, 36, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, D.; Qian, K.; Chen, K.; Wang, D. Development and Test of Reciprocating Kneading Peanut Shelling Device. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2024, 46, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Yang, D.; Gao, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, M.; Shen, Y. Design and Test on Plot Peanut Sheller with Vertical Tapered Drum. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Nie, Q.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Long, S.; Zhang, H. Development of cone disc type shelling mechanism for peanut seeds. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, M.; Wei, H.; Yan, J.; Wu, F. Experimental Study and Parameter Optimization of Key Components in a Drum-Concave Screen Peanut Sheller. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2018, 46, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryeh, E.A. Physical properties of bambara groundnuts. J. Food Eng. 2001, 47, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, A.; Ugurluay, S.; Güzel, E.; Özcan, M.T. Mechanical behavior of hulled peanut and its kernel during the shelling process. Philipp. Agric. Sci. 2009, 92, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liang, M.; Xie, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, M. Study on the Mechanical Shelling Characteristics of Different Peanut Varieties. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payman, S.H.; Ajdadi, F.R.; Bagheri, I.; Alizadeh, M.R. Effect of moisture content on some engineering properties of peanut varieties. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, S.; Donahaye, E.; Kleinerman, R.; Haham, H. The influence of temperature and moisture content on the germination of peanut seeds. Peanut Sci. 1989, 16, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Xie, J.; Feng, M.; Chen, Z.; Chang, L.; Jiang, Y. Effect of Moisture Content of Peanut Pod on the Efficiency and Quality of Mechanical Husking. J. Peanut Sci. 2021, 50, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.; You, Z.; Xie, H. Design and test of small peanut sheller. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2025, 46, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, M.; Peng, J.; Ding, Q.; Peng, B.; Ma, C. Optimization of Material for Key Components and Parameters of Peanut Sheller Based on Hertz Theory and Box–Behnken Design. Agriculture 2022, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Du, X.; Gao, L. Damage characteristics and regularity of peanut kernels under mechanical shelling. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2010, 26, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Peng, B.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wu, F. General situation and development of peanut shelling technology and equipment in China. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2010, 38, 581–582. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, B.; Xie, J.; Feng, M.; Chen, Z.; Chang, L.; Jiang, Y. The influence of different types of peanut pods on the mechanical shelling effect. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Xie, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; An, J.; Wei, H.; Zhang, H. Peanut-shelling technologies and equipment: A review of recent developments. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. Experimental Research and Optimization Design of Key Components on Peanut Sheller of Blowing and Rubbing; Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Yi, S.; Zhang, J.; Bao, Y. Establishment of millet threshing and separating model and optimization of harvester parameters. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 11251–11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăduț, N.; Biriş, S.; Cârdei, P.; Găgeanu, I.; Cujbescu, D.; Ungureanu, N.; Popa, L.; Perişoară, L.; Matei, G.; Teliban, G. Contributions to the Mathematical Modeling of the Threshing and Separation Process in An Axial Flow Combine. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miu, P.I.; Kutzbach, H. Modeling and simulation of grain threshing and separation in threshing units—Part I. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 60, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Wei, W.; Shang, K.; Zhang, Y. Research on the Contact Dynamics of Binary Non-Spherical Particles Based on Hertz Theory. J. Food Process Eng. 2025, 48, e70070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Yang, H. Study on the Damage Characteristics of Wheat Kernels under Continuous Compression Conditions. Foods 2024, 13, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Fu, J. The influence of size effect on the bending fatigue life of FRP composite. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2025, 43, 7884–7895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Lu, A.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z. Aerodynamic characteristics of lotus seed mixtures and test on pneumatic separating device for lotus seed and contaminants. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2015, 31, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.; Tao, D.; Gao, J. Dynamic characteristics and factors affecting performance of air-stream cleaning windmill. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2006, 22, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Suhua 0537. China Peanut Data Center. RiceData—Chinese Peanut Varieties and Their Pedigree Database. Available online: http://peanut.cropdb.cn/variety/varis/602611.htm (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- GB/T 5262-2008; Measuring Methods for Agricultural Machinery Testing Conditions-General Rules. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. Moisture Measurement—Peanuts; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St Joseph, MI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 20264-2006; Grain and Oilseed-Determination of Moisture Content-Twice Drying Method. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Blankenship, P.D.; Person, J.L. Effects of Restoring Peanut Moisture with Aeration Before Shelling. Peanut Sci. 1975, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K.L.; Hagan, A.K. Temperature and Moisture Conditions That Affect Aflatoxin Contamination of Peanuts. Peanut Sci. 2015, 42, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacilik, K.; Öztürk, R.; Keskin, R. Some Physical Properties of Hemp Seed. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 86, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NYT994-2006; Operating Quality for Peanut Shelling Machine. China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2006.

- DG/T 128-2022; Peanut Sheller. Agricultural Mechanization General Station of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Liu, M.; Gao, X.; Hu, Z. Research on Cause and Counter measures of The Rub-style Peanut Shelling Equipment Effect. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2012, 64, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H. Research on Key Technologies for Mechanized Peanut Shelling; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 39–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. Key Technologies for Mechanization of Peanut Production; Jiangsu University Press: Zhenjiang, China, 2017; pp. 226–240. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Overall dimensions (mm) | 1160 × 680 × 410 |

| Motor power/Rated speed (kW/rpm) | 1.5/1400 |

| Fan speed range (m/s) | 6–10 |

| Shelling drum diameter/length (mm) | 208/148 |

| Shelling drum rotational speed (rpm) | 0–275 |

| Shelling chamber-drum side clearance (mm) | 21 |

| Drum-concave screen gap adjustment range (mm) | 20–32 |

| Concave screen grid bar spacing range (mm) | 7–12 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Shaft length /radius (mm) | 324/11 |

| Arc-plate width (mm) | 120 |

| Silicone plate thickness/hardness (mm/HA) | 10/40 |

| Drum width /radius (mm) | 148/104 |

| Side plate width /radius /hole slot length (mm) | 4/94/20 |

| Side strip length /width/height (mm) | 10/35/15 |

| Shaft sleeve length/thickness (mm) | 24/5 |

| Positioning dimension (mm) | 67/124/133 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Concave screen length /width /height (mm) | 293/180/90 |

| Concave screen central angle (°) | 138 |

| Arc-side inner /outer radius /length /width/thickness (mm) | 125/135/255/10/3 |

| Hanging ear length /thickness (mm) | 174/3 |

| Circular grid bar length /diameter (mm) | 180/5 |

| Grid bar spacing range (mm) | 7~12 |

| Parameters | Pods | Kernels |

|---|---|---|

| Three-diameter dimension (mm) | 30.13 × 15.37 × 14.89 | 14.36 × 10.30 × 9.14 |

| Geometric mean diameter (mm) | 19.03 | 11.06 |

| Hundred-grain weight (g) | 196.43 | 95.30 |

| Initial moisture content (%) | 7.58% | 5.20% |

| Spherical degree | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| Volume–weight (kg/m3) | 256 | 678 |

| Break/Damage force (N) | 61.23 | 40.16 |

| Level | Rotational Speed/rpm | Shelling Spacing/mm | Moisture Content/% | Silicone Hardness/HA | Side Strip Length/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150 | 14 | 8 | 10 | 0 |

| 2 | 170 | 17 | 10 | 20 | 5 |

| 3 | 190 | 20 | 12 | 30 | 10 |

| 4 | 210 | 23 | 14 | 40 | 15 |

| 5 | 230 | 26 | 16 | 50 | 20 |

| 6 | 250 | 29 | 18 | 60 | - |

| 7 | 270 | 32 | 20 | 70 | - |

| Level | Moisture Content A/% | Rotational Speed B/rpm | Shelling Spacing C/mm | Silicone Hardness D/HA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 8 | 190 | 20 | 20 |

| 0 | 11 | 220 | 23 | 40 |

| 1 | 14 | 250 | 26 | 60 |

| No. | Influence Factors | Response Indicators | No. | Influence Factors | Response Indicators | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 12.96% | 94.14% | 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6.56% | 95.52% |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 3.89% | 89.19% | 17 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 16.37% | 97.33% |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13.01% | 95.95% | 18 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 5.76% | 93.35% |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5.99% | 94.89% | 19 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8.47% | 96.37% |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 11.51% | 96.22% | 20 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.92% | 88.56% |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 5.19% | 92.89% | 21 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 6.29% | 90.90% |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 12.01% | 96.50% | 22 | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 8.74% | 94.14% |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.70% | 93.56% | 23 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 8.22% | 93.49% |

| 9 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 13.20% | 96.25% | 24 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9.80% | 94.98% |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 3.27% | 90.27% | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.07% | 95.89% |

| 11 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13.43% | 96.15% | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.81% | 95.22% |

| 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.58% | 90.47% | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.66% | 95.73% |

| 13 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 10.93% | 95.83% | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.59% | 95.34% |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 11.07% | 96.63% | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.13% | 96.19% |

| 15 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 4.25% | 91.09% | |||||||

| Source | SS | DF | MS | F-Value | p-Value | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 385.3400 | 14 | 27.5200 | 125.0400 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A | 208.5700 | 1 | 208.5700 | 947.4900 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B | 6.1800 | 1 | 6.1800 | 28.0800 | 0.0001 | ** |

| C | 99.5500 | 1 | 99.5500 | 452.2200 | <0.0001 | ** |

| D | 3.5500 | 1 | 3.5500 | 16.1300 | 0.0013 | ** |

| AB | 1.0500 | 1 | 1.0500 | 4.7900 | 0.0461 | * |

| AC | 6.4000 | 1 | 6.4000 | 29.0900 | <0.0001 | ** |

| AD | 1.0900 | 1 | 1.0900 | 4.9400 | 0.0431 | * |

| BC | 1.1800 | 1 | 1.1800 | 5.3400 | 0.0366 | * |

| BD | 0.1894 | 1 | 0.1894 | 0.8606 | 0.3693 | |

| CD | 9.00 × 10−6 | 1 | 9.00 × 10−6 | 0.0000 | 0.9950 | |

| A2 | 29.4800 | 1 | 29.4800 | 133.9000 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 19.6200 | 1 | 19.6200 | 89.1300 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C2 | 17.0200 | 1 | 17.0200 | 77.3100 | <0.0001 | ** |

| D2 | 23.2600 | 1 | 23.2600 | 105.6700 | <0.0001 | ** |

| Residual | 3.0800 | 14 | 0.2201 | |||

| Lack of fit | 2.8500 | 10 | 0.2855 | 5.0300 | 0.0666 | |

| Error | 0.2269 | 4 | 0.0567 | |||

| Total | 388.4300 | 28 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9921 |

| Source | SS | DF | MS | F-Value | p-Value | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 159.9500 | 14 | 11.4300 | 25.5800 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A | 75.7400 | 1 | 75.7400 | 169.5700 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B | 22.4000 | 1 | 22.4000 | 50.1500 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C | 26.5900 | 1 | 26.5900 | 59.5300 | <0.0001 | ** |

| D | 1.9700 | 1 | 1.9700 | 4.4200 | 0.0541 | |

| AB | 1.9400 | 1 | 1.9400 | 4.3500 | 0.0557 | |

| AC | 3.6800 | 1 | 3.6800 | 8.2300 | 0.0124 | * |

| AD | 0.0021 | 1 | 0.0021 | 0.0048 | 0.9457 | |

| BC | 3.3100 | 1 | 3.3100 | 7.4100 | 0.0165 | * |

| BD | 0.7680 | 1 | 0.7680 | 1.7200 | 0.2109 | |

| CD | 0.0389 | 1 | 0.0389 | 0.0872 | 0.7722 | |

| A2 | 15.4100 | 1 | 15.4100 | 34.4900 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 6.6800 | 1 | 6.6800 | 14.9500 | 0.0017 | ** |

| C2 | 0.0009 | 1 | 0.0009 | 0.0021 | 0.9641 | |

| D2 | 7.0400 | 1 | 7.0400 | 15.7600 | 0.0014 | ** |

| Residual | 6.2500 | 14 | 0.4467 | |||

| Lack of fit | 5.6300 | 10 | 0.5630 | 3.6100 | 0.1137 | |

| Error | 0.6235 | 4 | 0.1559 | |||

| Total | 166.2100 | 28 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9624 |

| No. | Breakage Rate% | Damage Rate% | MDR% | SE% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.86 | 2.55 | 4.41 | 95.84 |

| 2 | 2.21 | 3.86 | 6.07 | 94.76 |

| 3 | 1.95 | 2.17 | 4.12 | 96.39 |

| 4 | 1.15 | 2.69 | 3.84 | 93.83 |

| 5 | 2.37 | 2.86 | 5.23 | 95.21 |

| Mean value | 1.91 | 2.83 | 4.73 | 95.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Sun, C.; An, J.; Xie, H.; Hu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wei, H. Optimization of a Low-Loss Peanut Mechanized Shelling Technology Based on Moisture Content, Flexible Materials, and Key Operating Parameters. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2365. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222365

Liao X, Liu T, Wang J, Liu M, Sun C, An J, Xie H, Hu Z, Shen Y, Wei H. Optimization of a Low-Loss Peanut Mechanized Shelling Technology Based on Moisture Content, Flexible Materials, and Key Operating Parameters. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2365. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222365

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Xuan, Tao Liu, Jiannan Wang, Minji Liu, Chenyang Sun, Jiyou An, Huanxiong Xie, Zhichao Hu, Yi Shen, and Hai Wei. 2025. "Optimization of a Low-Loss Peanut Mechanized Shelling Technology Based on Moisture Content, Flexible Materials, and Key Operating Parameters" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2365. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222365

APA StyleLiao, X., Liu, T., Wang, J., Liu, M., Sun, C., An, J., Xie, H., Hu, Z., Shen, Y., & Wei, H. (2025). Optimization of a Low-Loss Peanut Mechanized Shelling Technology Based on Moisture Content, Flexible Materials, and Key Operating Parameters. Agriculture, 15(22), 2365. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222365