Effect of Irrigation with Saline Water on Germination, Physiology, Growth, and Yield of Durum Wheat Varieties on Silty Clay Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Soil Sampling, and Assessment of Physicochemical Properties

2.2. Plant Material, Experimental Setup, and Crop Management Practices

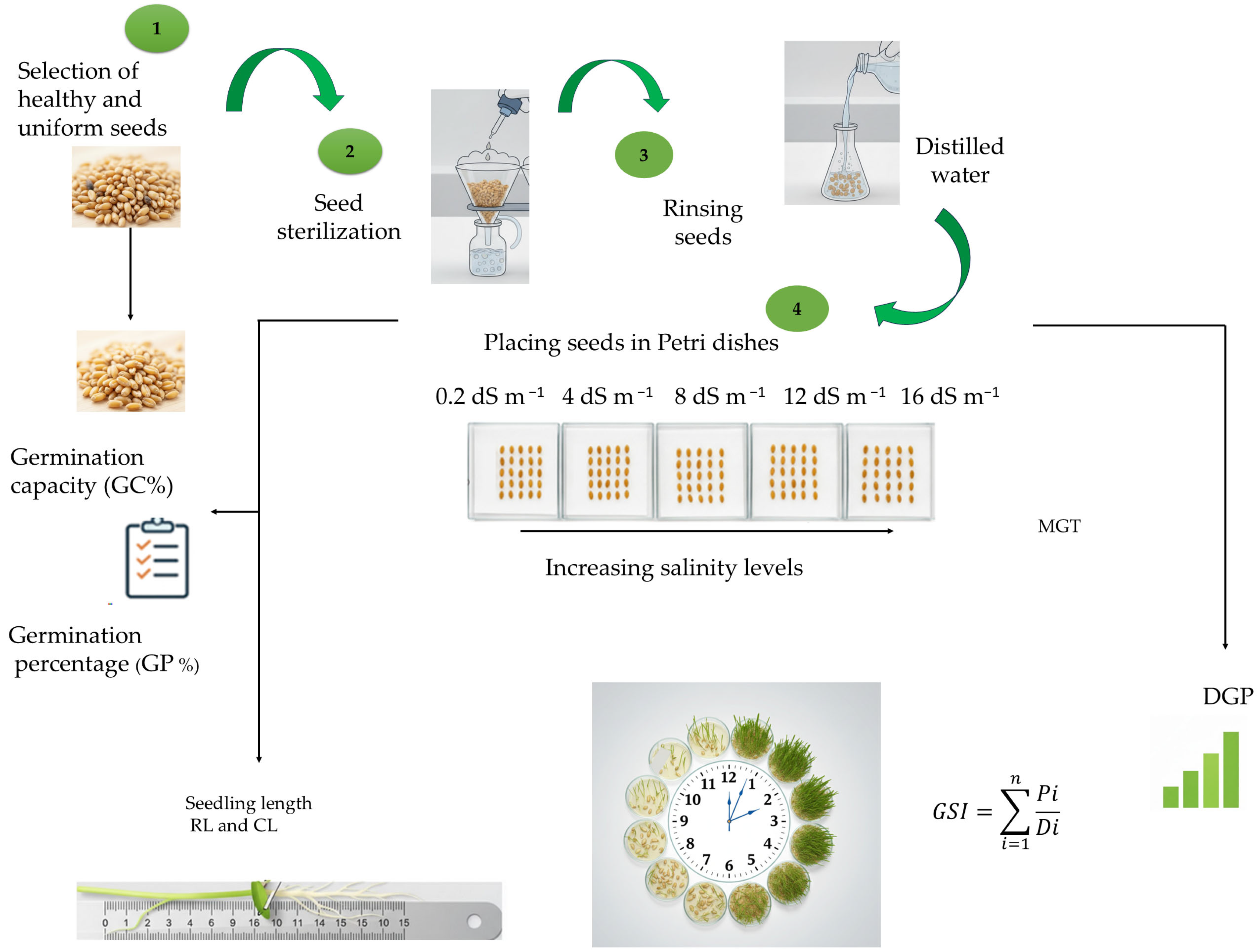

2.3. Germination Test and Germination Indicators

2.4. Measurement of Growth Parameters and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Under Controlled Conditions

2.5. Yield Component Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

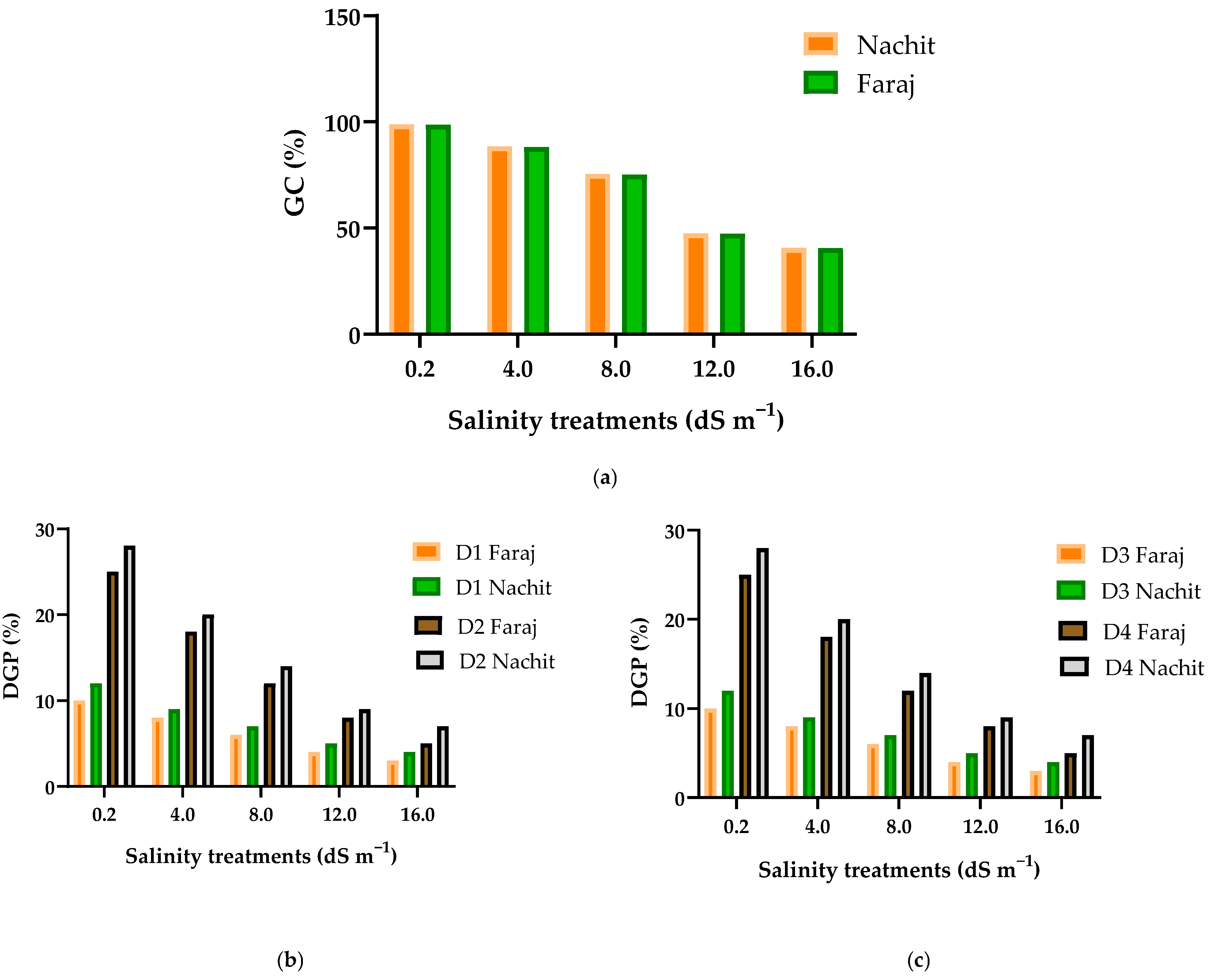

3.1. Daily Germination Progress of Two Durum Wheat Varieties Under Varying Salinity Levels

3.2. Effects of NaCl Treatments on Germination Stress Index (GSI) and Mean Germination Time (MGT) in Two Durum Wheat Varieties

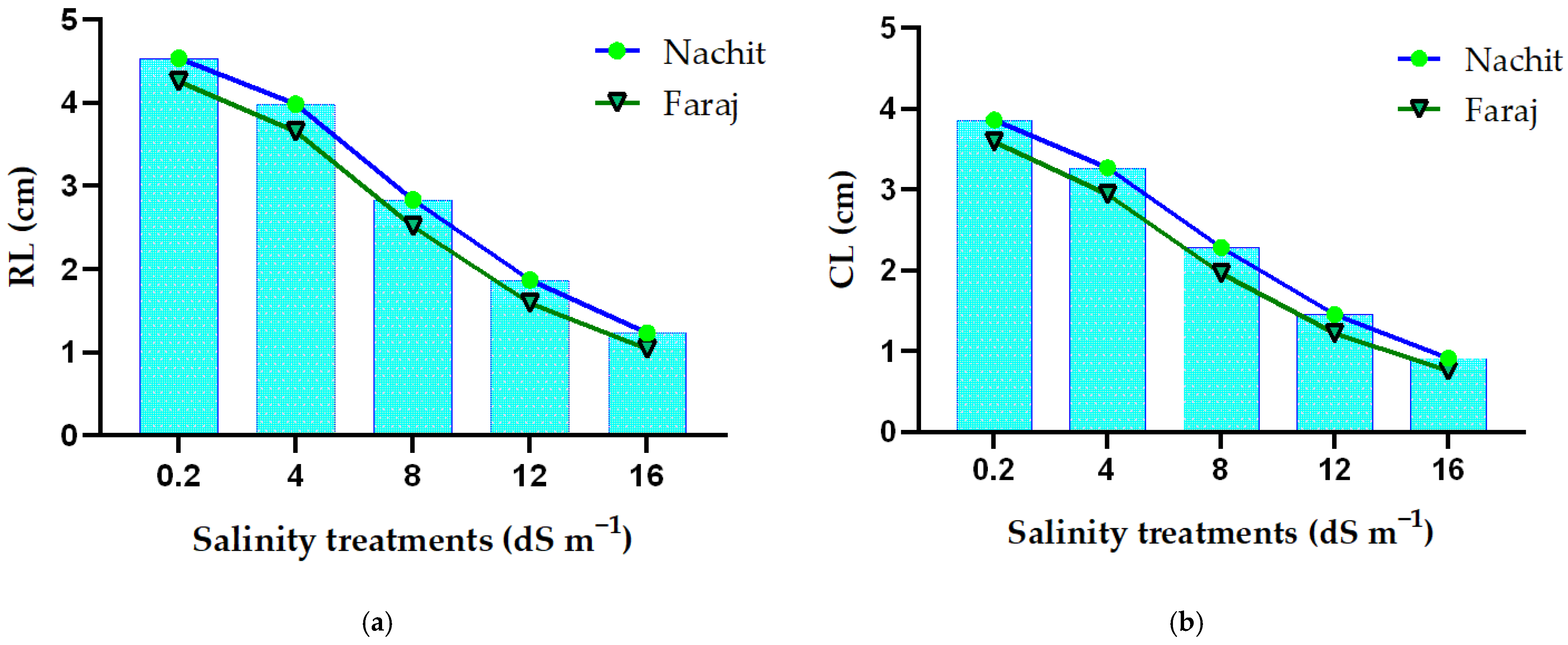

3.3. Response of Durum Wheat Root and Coleoptile Growth to Gradual Salinity Stress

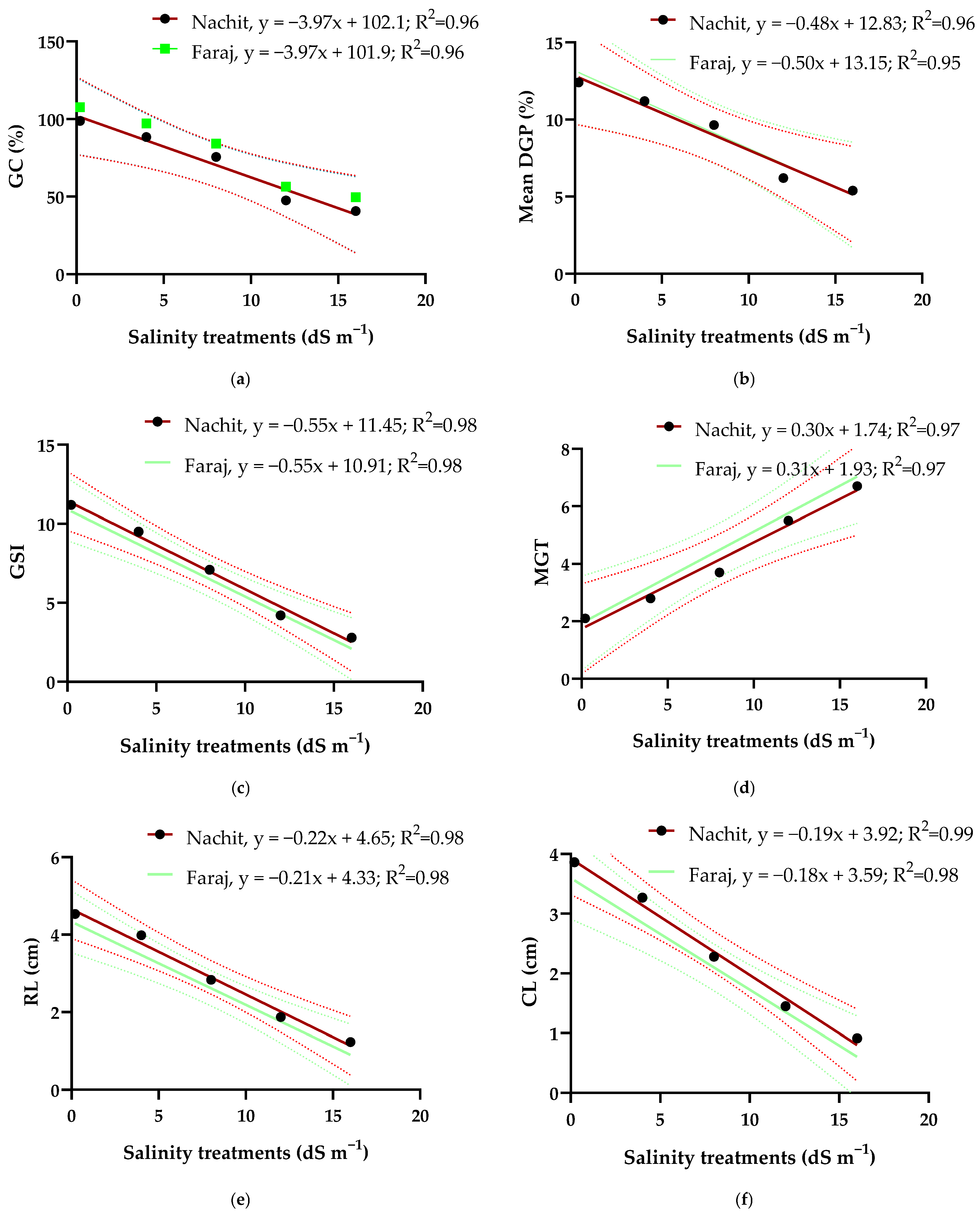

3.4. Relationships Between Salinity Treatments, Germination and Early Seedling Growth Parameters

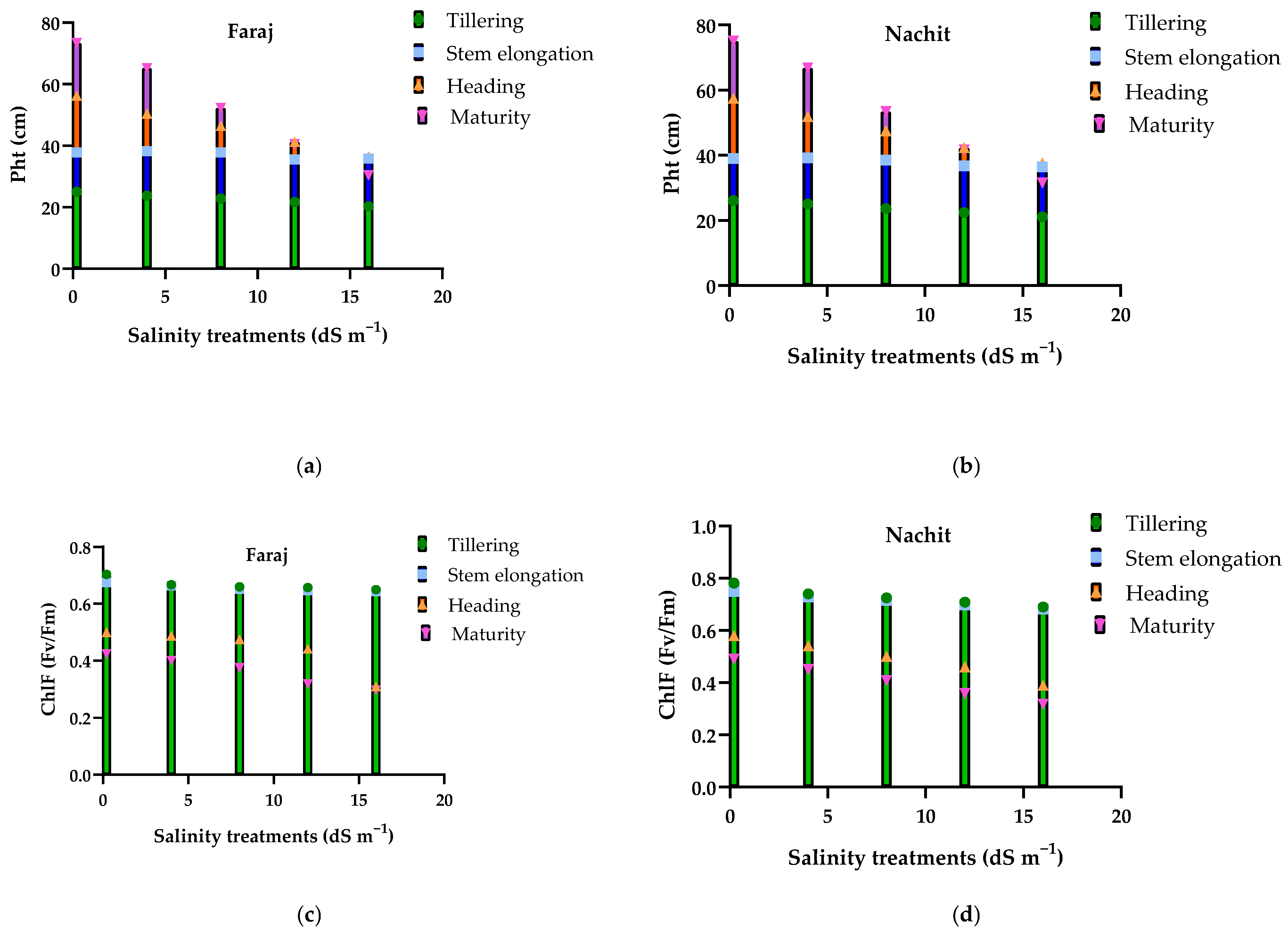

3.5. Effects of Salinity on Plant Development, Leaf Number, and Chlorophyll Fluorescence (Fv/Fm) in Durum Wheat

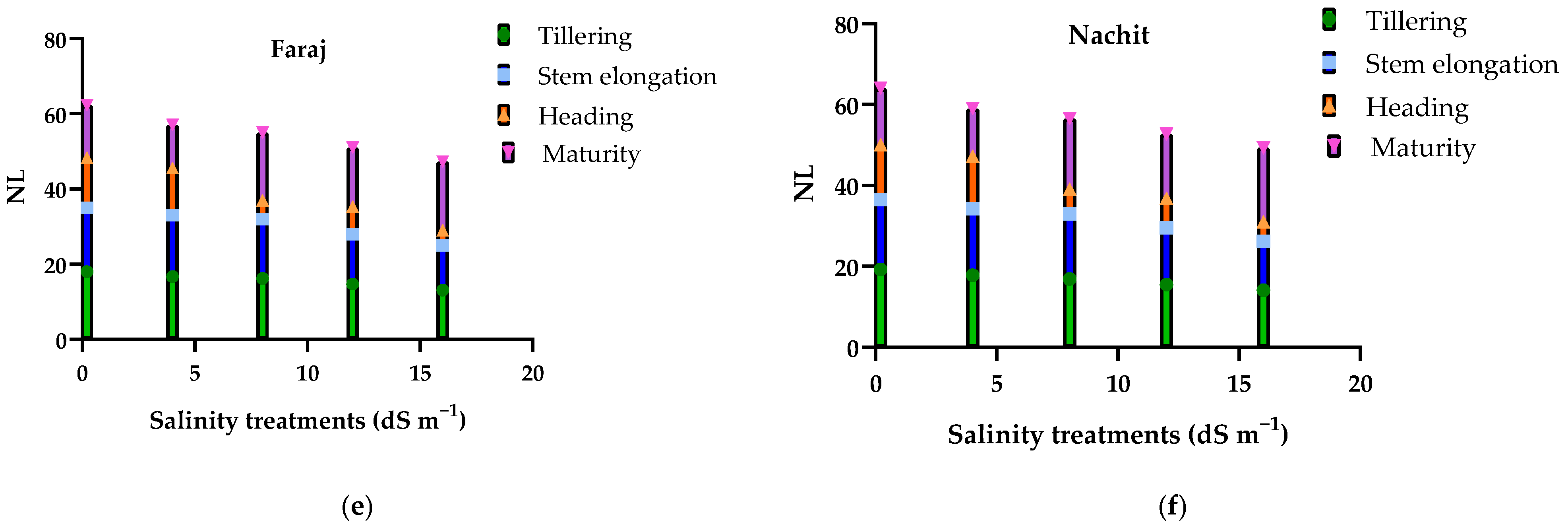

3.6. Evaluation of Yield Components and Salinity Tolerance Limits in Two Durum Wheat Varieties

3.7. Relationships Between Grain Performance and Irrigation Salinity in Durum Wheat

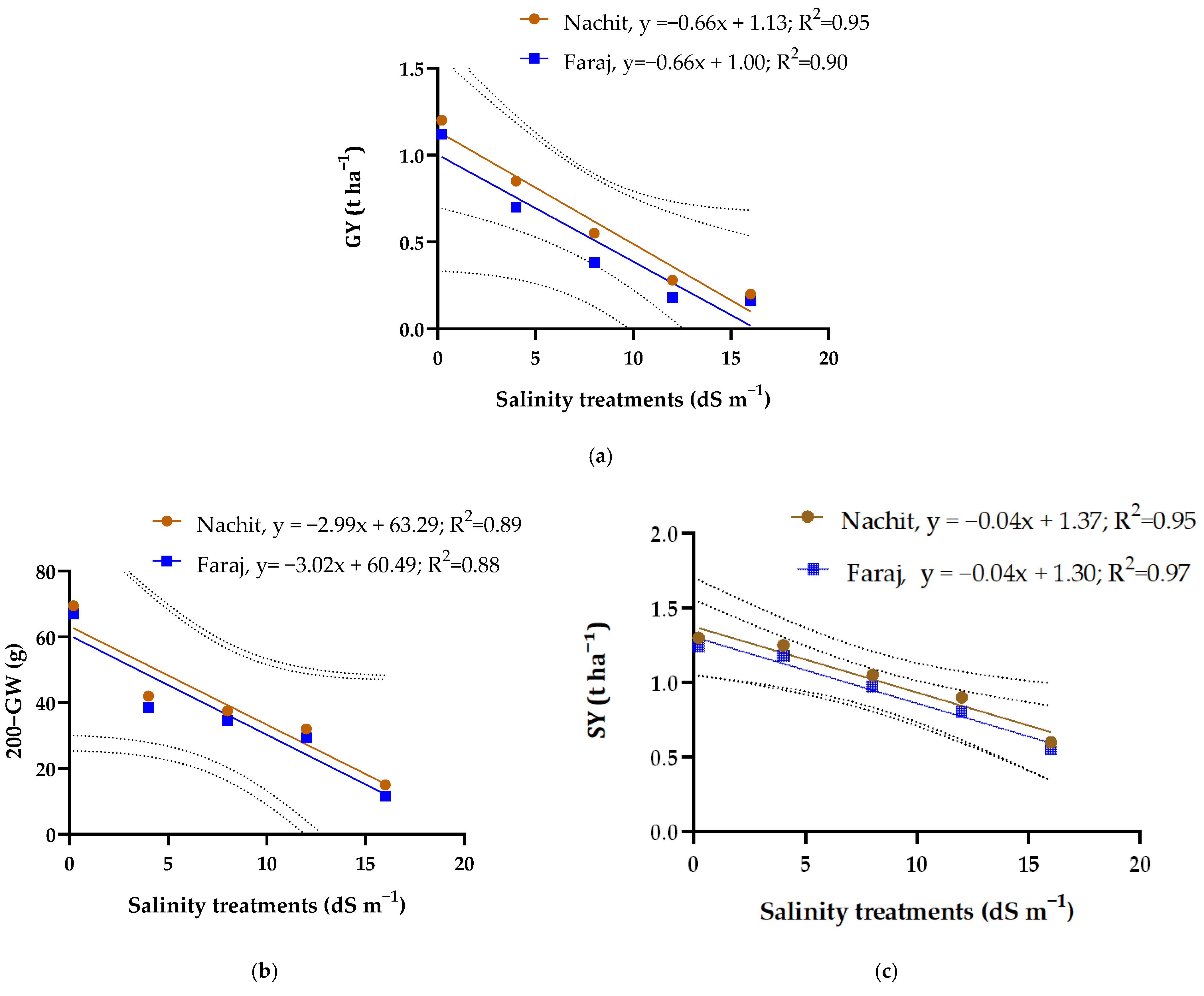

3.8. Heatmap of Correlations Between Soil Chemical Parameters, Growth Traits, and Yield Components in Durum Wheat

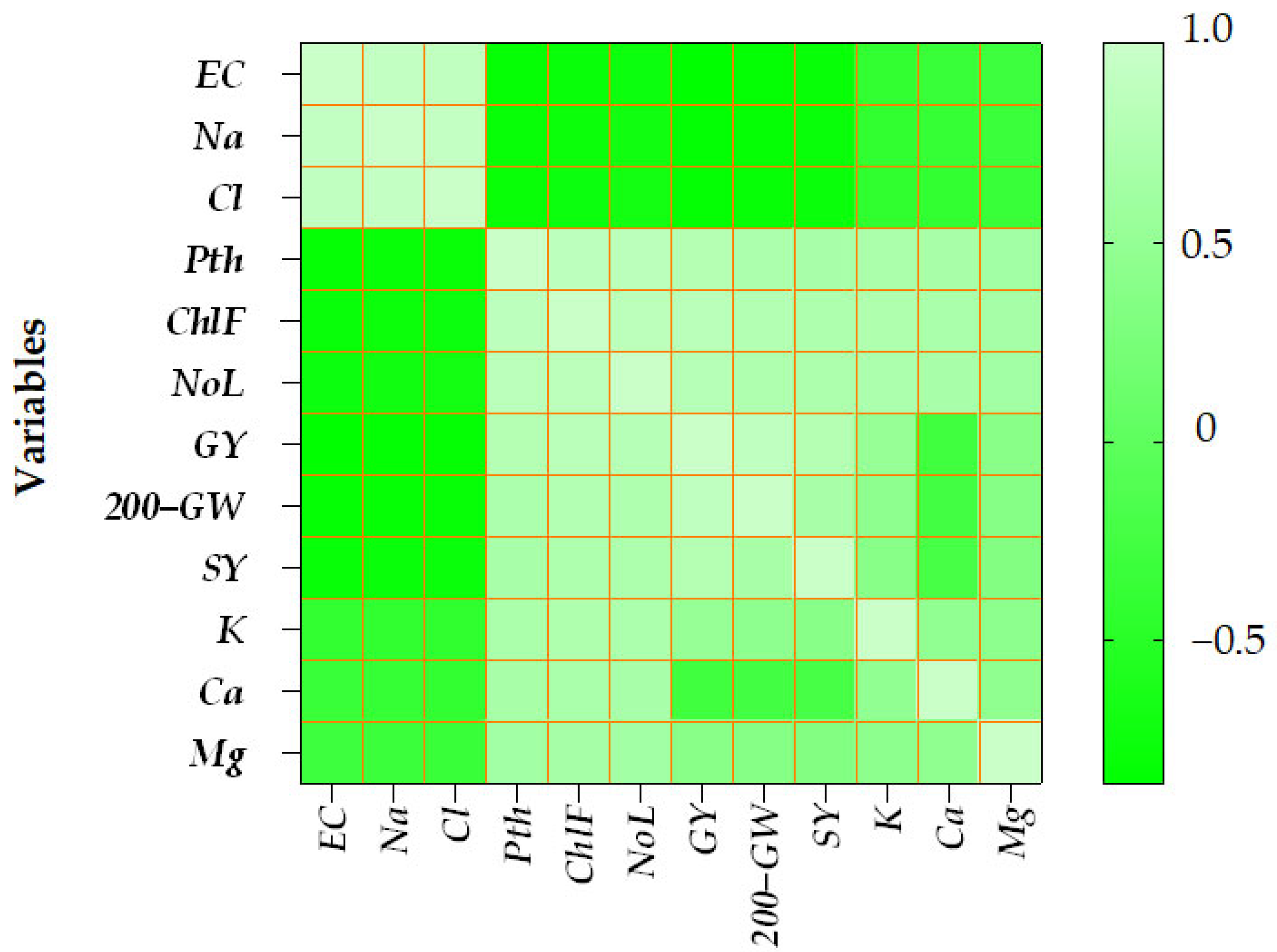

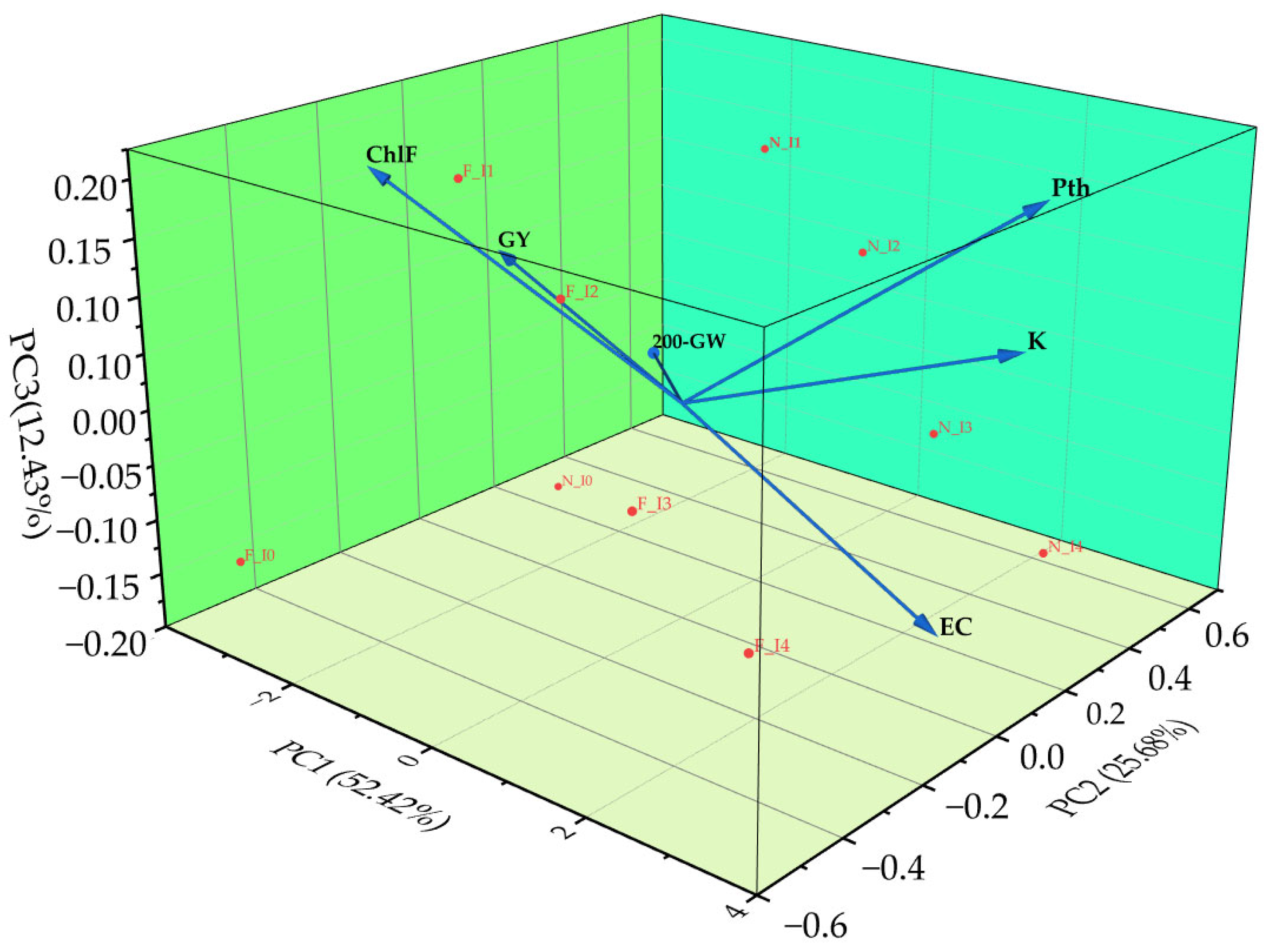

3.9. Principal Component Analysis Revealing the Relationships Among Soil Chemistry, Growth, and Yield Under Salinity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. World Food Day 2023 Highlights the Critical Role of Water in Achieving Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ingrao, C.; Strippoli, R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water Scarcity in Agriculture: An Overview of Causes, Impacts and Approaches for Reducing the Risks. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmjid, Z.; Hallam, J.; Dakak, H.; Douaik, A.; Oumaima, I. Soil Salinity: A Challenge for the Resilience of Ecosystems and the Sustainability of Moroccan Agriculture. Afr. Med. Agric. J. 2024, 143, 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Šimůnek, J.; Shi, H.; Chen, N.; Hu, Q. Optimizing drip irrigation with alternate use of fresh and brackish waters by analyzing salt stress: The experimental and simulation approaches. Soil. Tillage Res. 2022, 222, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Liu, X. Reclamation effect of freezing saline water irrigation on heavy saline-alkali soil in the Hetao Irrigation District of North China. Catena 2021, 204, 105420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, K.; Mondal, S.; Gorai, S.; Singh, A.P.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, T.; Roy, A.; Hembram, S.; Gaikwad, D.J.; Mondal, S.; et al. Impacts of salinity stress on crop plants: Improving salt tolerance through genetic and molecular dissection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1241736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zheng, C.; Ning, S.; Cao, C.; Li, K.; Dang, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Impacts of Long-Term Saline Water Irrigation on Soil Properties and Crop Yields under Maize–Wheat Crop Rotation. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 280, 108383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turki, N.; Shehzad, T.; Harrabi, M.; Okuno, K. Mapping Novel QTLs for Tolerance to Salt Stress at the Late Vegetative Stage in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum L.). J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xynias, I.N.; Mylonas, I.; Korpetis, E.G.; Ninou, E.; Tsaballa, A.; Avdikos, I.D.; Mavromatis, A.G. Durum Wheat Breeding in the Mediterranean Region: Current Status and Future Prospects. Agronomy 2020, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddiq, M.S.; Afzal, I.; Basra, S.M.A.; Iqbal, S.; Ashraf, M. Sodium Exclusion Affects Seed Yield and Physiological Traits of Wheat Genotypes Grown Under Salt Stress. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 2020, 20, 1442–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggini, G.; Namoune, H.; Abecassis, J.; Cuq, B. Other Traditional Durum-Derived Products. In Durum Wheat; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 177–199. ISBN 978-1-891127-65-6. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, P.; Kaur, H.; Tyagi, V.; Saini, P.; Ahmed, N.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Sheikh, I. Nutritional Value and End-Use Quality of Durum Wheat. CEREAL Res. Commun. 2023, 51, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Kumar, A.; Sehrawat, N.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, N.; Lata, C.; Mann, A. Effect of Saline Irrigation on Plant Water Traits, Photosynthesis and Ionic Balance in Durum Wheat Genotypes. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2510–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouras, E.; Jarlan, L.; Khabba, S.; Er-Raki, S.; Dezetter, A.; Sghir, F.; Tramblay, Y. Assessing the Impact of Global Climate Changes on Irrigated Wheat Yields and Water Requirements in a Semi-Arid Environment of Morocco. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X. Environmental Groundwater Depth for Groundwater-Dependent Terrestrial Ecosystems in Arid/Semiarid Regions: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadir, M.; Qureshi, A.S.; Cheraghi, S.A.M. Extent and Characterisation of Salt-affected Soils in Iran and Strategies for Their Amelioration and Management. Land Degrad. Dev. 2008, 19, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; An, F.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z. Variations on Soil Salinity and Sodicity and Its Driving Factors Analysis under Microtopography in Different Hydrological Conditions. Water 2016, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P.; Parisi, D.; Woodrow, P.; Pontecorvo, G.; Massaro, G.; Annunziata, M.G.; Fuggi, A.; Sulpice, R. Salt-Induced Accumulation of Glycine Betaine Is Inhibited by High Light in Durum Wheat. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, C.; Soni, S.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, A.; Pooja, P.; Mann, A.; Rani, S. Adaptive Mechanism of Stress Tolerance in Urochondra (Grass Halophyte) Using Roots Study. Ind. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 89, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R. Comparative Physiology of Salt and Water Stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchimanchi, B.R.; Ripoll-Bosch, R.; Steenstra, F.A.; Thomas, R.; Oosting, S.J. The Impact of Intensive Farming Systems on Groundwater Availability in Dryland Environments: A Watershed Level Study from Telangana, India. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 5, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.-Z.; Darzi-Naftchali, A.; Karandish, F.; Ritzema, H.; Solaimani, K. Enhancing Agricultural Sustainability with Water and Crop Management Strategies in Modern Irrigation and Drainage Networks. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, P.S.; Ramos, T.B.; Ben-Gal, A.; Pereira, L.S. Coping with Salinity in Irrigated Agriculture: Crop Evapotranspiration and Water Management Issues. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 227, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Lhaj, M.O.; Dakak, H.; Manhou, K.; Zouahri, A. Monte Carlo Simulation for Evaluating Spatial Dynamics of Toxic Metals and Potential Health Hazards in Sebou Basin Surface Water. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hnilickova, H.; Kraus, K.; Vachova, P.; Hnilicka, F. Salinity Stress Affects Photosynthesis, Malondialdehyde Formation, and Proline Content in Portulaca oleracea L. Plants 2021, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousfi, S.; Serret, M.D.; Márquez, A.J.; Voltas, J.; Araus, J.L. Combined Use of δ13 C, δ18 O and δ15 N Tracks Nitrogen Metabolism and Genotypic Adaptation of Durum Wheat to Salinity and Water Deficit. New Phytol. 2012, 194, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdehpour, Z.; Ehsanzadeh, P. Concurrence of Ionic Homeostasis Alteration and Dry Mass Sustainment in Emmer Wheats Exposed to Saline Water: Implications for Tackling Irrigation Water Salinity. Plant Soil 2019, 440, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattabi, D.; Sakar, E.H.; Louahlia, S. Flag Leaf Tolerance Study in Moroccan Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Varieties Submitted to a Severe Salt Stress. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 2787–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, S.; Serret, M.D.; Voltas, J.; Araus, J.L. Effect of Salinity and Water Stress during the Reproductive Stage on Growth, Ion Concentrations, Δ13C, and δ15N of Durum Wheat and Related Amphiploids. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3529–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Soil Salinization Management for Sustainable Development: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, H.; Lan, L.; Huang, R.; Deng, X.; Peng, Y. Effects of Exponential N Application on Soil Exchangeable Base Cations and the Growth and Nutrient Contents of Clonal Chinese Fir Seedlings. Plants 2023, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, F.; Tian, L.; He, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, F. Soil Physicochemical Properties and Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Yield under Brackish Water Mulched Drip Irrigation. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199, 104592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, F.; Yang, P.; Ren, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wei, R.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Irrigation Water Salinity on Soil Properties, N2O Emission and Yield of Spring Maize under Mulched Drip Irrigation. Water 2019, 11, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feike, T.; Chen, S.; Shao, L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X. Effects of Saline Irrigation on Soil Salt Accumulation and Grain Yield in the Winter Wheat-Summer Maize Double Cropping System in the Low Plain of North China. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 2886–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, G.; Yao, R.; Yu, S. Impact of Irrigation Volume and Water Salinity on Winter Wheat Productivity and Soil Salinity Distribution. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 149, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Luo, J.; Park, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Masin, R. Soil Salinization in Agriculture: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Combining Nature-Based Solutions and Bioengineering. iScience 2024, 27, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rham, I.; Bouchiha, F.; Kharbouche, H.A.; El Maataoui, S.; Radi, H.; Choukrane, B.; Karama, M.; Ouhboun, R.; Hmouni, D.; Mazri, M.A. Effects of Medium Components on Cactus Pear (Opuntia Ficus-Indica (L.) Mill. Genotype ‘M2’) Organogenesis, and Assessment of Transplanting Techniques andVitroplant Fruit Quality. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2025, 160, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Torre, S.; Garcia-Caparrós, P.; Nogales, A.; Abreu, M.M.; Santos, E.; Cortinhas, A.L.; Caperta, A.D. Sustainable Agricultural Management of Saline Soils in Arid and Semi-Arid Mediterranean Regions through Halophytes, Microbial and Soil-Based Technologies. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 212, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, E.S.A.; El-Sobky, E.-S.E.A.; Farag, H.I.A.; Yasin, M.A.T.; Attia, A.; Rady, M.O.A.; Awad, M.F.; Mansour, E. Sowing Date and Genotype Influence on Yield and Quality of Dual-Purpose Barley in a Salt-Affected Arid Region. Agronomy 2021, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.A.; Soccio, M.; Laus, M.N.; Flagella, Z. Influence of Drought and Salt Stress on Durum Wheat Grain Quality and Composition: A Review. Plants 2021, 10, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, F.; Ammar, K.; Solís, I. Global Changes in Cultivated Area and Breeding Activities of Durum Wheat from 1800 to Date: A Historical Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate-Data.org. Témara, Morocco–Climate Data by Month. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/africa/morocco/temara-%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A9/temara-%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A9-764491/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Manhou, K.; Moussadek, R.; Yachou, H.; Zouahri, A.; Douaik, A.; Hilal, I.; Ghanimi, A.; Hmouni, D.; Dakak, H. Assessing the Impact of Saline Irrigation Water on Durum Wheat (Cv. Faraj) Grown on Sandy and Clay Soils. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRB (World Reference Base for Soil Resources). International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136461-5. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, J.C.; Gunn, B.V. Treatments to Promote Seed Germination in Australian Acacias. In Proceedings of the an International Workshop, Gympie, Australia, 4–7 August 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, J.D. Speed of Germination—Aid in Selection and Evaluation for Seedling Emergence and Vigor. Crop Sci. 1962, 2, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenchley, J.L.; Probert, R.J. Seed Germination Responses to Some Environmental Factors in the Seagrass Zostera Capricorni from Eastern Australia. Aquat. Bot. 1998, 62, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis: A Guide to Good Practice and Understanding Some New Applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häder, D.-P.; Herrmann, H.; Schäfer, J.; Santas, R. Photosynthetic Fluorescence Induction and Oxygen Production in Two Mediterranean Cladophora Species Measured on Site. Aquat. Bot. 1997, 56, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, D.; Luna, B.; Ourcival, J.-M.; Kavgacı, A.; Sirca, C.; Mouillot, F.; Arianoutsou, M.; Moreno, J.M. Germination Sensitivity to Water Stress in Four Shrubby Species across the Mediterranean Basin. Plant Biol. J. 2017, 19, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nautiyal, P.C.; Sivasubramaniam, K.; Dadlani, M. Seed Dormancy and Regulation of Germination. In Seed Science and Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 39–66. ISBN 978-981-19588-8-5. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam, T.; Shen, G.; Esmaeili, N.; Zhang, H. Plants’ Response Mechanisms to Salinity Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sabagh, A.; Islam, M.S.; Skalicky, M.; Ali Raza, M.; Singh, K.; Anwar Hossain, M.; Hossain, A.; Mahboob, W.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ratnasekera, D.; et al. Salinity Stress in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in the Changing Climate: Adaptation and Management Strategies. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 661932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; James, R.A. Screening Methods for Salinity Tolerance: A Case Study with Tetraploid Wheat. Plant Soil. 2003, 253, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwando, E.; Han, Y.; Angessa, T.T.; Zhou, G.; Hill, C.B.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Li, C. Genome-Wide Association Study of Salinity Tolerance During Germination in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi Dehnavi, A.; Zahedi, M.; Ludwiczak, A.; Cardenas Perez, S.; Piernik, A. Effect of Salinity on Seed Germination and Seedling Development of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) Genotypes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerji, N.; Van Hoorn, J.W.; Hamdy, A.; Mastrorilli, M. Salinity Effect on Crop Development and Yield, Analysis of Salt Tolerance According to Several Classification Methods. Agric. Water Manag. 2003, 62, 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Rizwan, M.; Zia Ur Rehman, M.; Zubair, M.; Riaz, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Alharby, H.F.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Ali, S. Application of Co-Composted Farm Manure and Biochar Increased the Wheat Growth and Decreased Cadmium Accumulation in Plants under Different Water Regimes. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Akiba, T.; Moritsugu, M. Effects of High Concentrations of Sodium Chloride and Polyethylene Glycol on the Growth and Ion Absorption in Plants: I. Water Culture Experiments in a Greenhouse. Plant Soil. 1983, 75, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.A.; Rasmussen, A.; Traini, R.; Voß, U.; Sturrock, C.; Mooney, S.J.; Wells, D.M.; Bennett, M.J. Branching Out in Roots: Uncovering Form, Function, and Regulation. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish, L.; Rathinapriya, P.; Sagina Rency, A.; Antony Ceasar, S.; Prathibha, M.; Pandian, S.; Rameshkumar, R.; Ramesh, M. Effect of Salinity Stress on Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn): Histochemical and Morphological Analysis of Coleoptile and Coleorhizae. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2016, 222, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Hao, X.; Song, R.; Chen, S.; Wang, G.; Hua, L. Salt Stress in Wheat: A Physiological and Genetic Perspective. Plant Stress. 2025, 16, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, K.; Karmakar, S.; Dutta, D.; Pal, A.K.; Jana, K. Comparative Physiology of Salinity, Drought and Heavy Metal Stress during Seed Germination in Ricebean [Vigna Umbellata (Thunb.) Ohwi and Ohashi]. J. Crop Weed 2019, 15, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhou, K.; Moussadek, R.; Zouahri, A.; Ghanimi, A.; Sanad, H.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Hmouni, D.; Dakak, H. Performance, Agro-Morphological, and Quality Traits of Durum Wheat (Triticum turgidum L. Ssp. durum Desf.) Germplasm: A Case Study in Jemâa Shaïm, Morocco. Plants 2025, 14, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Thriving under Stress: How Plants Balance Growth and the Stress Response. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, A.H.K.; Matthew, C.; Uddin, M.J.; Bayazid, K.N. Salinity-Induced Reduction in Root Surface Area and Changes in Major Root and Shoot Traits at the Phytomer Level in Wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 3719–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairmansis, A.; Berger, B.; Tester, M.; Roy, S.J. Image-Based Phenotyping for Non-Destructive Screening of Different Salinity Tolerance Traits in Rice. Rice 2014, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, K.-C.; Cheng, T.-S.; Lee, C.; Lin, S.-H.; Tung, C.-W. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis in Diverse Rice Varieties Reveals the Positive Correlation between the Seedlings Salt Tolerance and Photosynthetic Efficiency. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-W.; Lee, T.-Y.; Nah, G.; Kim, D.-S. Potential of Thermal Image Analysis for Screening Salt Stress-Tolerant Soybean (Glycine Max). Plant Genet. Resour. 2014, 12, S134–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhodja, R.; Morales, F.; Abadia, A.; Gomez-Aparisi, J.; Abadia, J. Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Possible Tool for Salinity Tolerance Screening in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plant Physiol. 1994, 104, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awlia, M.; Nigro, A.; Fajkus, J.; Schmoeckel, S.M.; Negrão, S.; Santelia, D.; Trtílek, M.; Tester, M.; Julkowska, M.M.; Panzarová, K. High-Throughput Non-Destructive Phenotyping of Traits That Contribute to Salinity Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, A.; Huang, Z. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Salt Tolerance at the Seed Germination Stage and Yield-Related Traits in Brassica napus L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Kalhoro, N.; Rajpar, I.; Ali Kalhoro, S.; Ali, A.; Raza, S.; Ahmed, M.; Ali Kalhoro, F.; Ramzan, M.; Wahid, F. Effect of Salts Stress on the Growth and Yield of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Am. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 2257–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtaiwesh, F.A.; Rashed, H.F. Growth and Yield Responses of Libyan Hard Wheat (Triticum durum Desf) Genotypes to Salinity Stress. Zawia Univ. Bull. 2020, 22, 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K.; Yamaji, N.; Costa, A.; Okuma, E.; Kobayashi, N.I.; Kashiwagi, T.; Katsuhara, M.; Wang, C.; Tanoi, K.; Murata, Y.; et al. OsHKT1;4-Mediated Na+ Transport in Stems Contributes to Na+ Exclusion from Leaf Blades of Rice at the Reproductive Growth Stage upon Salt Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poustini, K.; Siosemardeh, A. Ion Distribution in Wheat Cultivars in Response to Salinity Stress. Field Crops Res. 2004, 85, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, H.; Nemati, H.; Farsi, M.; Jartoodeh, S.V. How Salinity Affect Germination and Emergence of Tomato Lines. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2011, 5, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Sanad, H.; Manhou, K.; Iben Halima, O.; Yachou, H.; Zouahri, A.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M. Application of Compost as an Organic Amendment for Enhancing Soil Quality and Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Growth: Agronomic and Ecotoxicological Evaluation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, C.; Gu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Ju, F.; Wang, S.; Hu, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Improving the soil K+/Na+ ratio under moderate salt stress synergistically increases the yield and quality of cotton fiber and cottonseed. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 185, 118441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataar, M.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Shabani, F. Soil Salinity and Matric Potential Interaction on Water Use, Water Use Efficiency and Yield Response Factor of Bean and Wheat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Asif, S.; Jang, Y.-H.; Park, J.-R.; Zhao, D.-D.; Kim, E.-G.; Kim, K.-M. Effect of Different Salts on Nutrients Uptake, Gene Expression, Antioxidant, and Growth Pattern of Selected Rice Genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 895282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Ashraf, M. Growth Stage-Based Modulation in Physiological and Biochemical Attributes of Two Genetically Diverse Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Cultivars Grown in Salinized Hydroponic Culture. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 6227–6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Tariq, M.N.; Amjad, M.; Sajjad, M.; Akram, M.; Imran, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Gondal, T.A.; Kenijz, N.; Kulikov, D. Salinity-Induced Changes in the Nutritional Quality of Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genotypes. AGRIVITA J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Lhaj, M.O.; Zahidi, K.; Dakak, H.; Manhou, K.; Zouahri, A. Ecological and Human Health Hazards Evaluation of Toxic Metal Contamination in Agricultural Lands Using Multi-Index and Geostatistical Techniques across the Mnasra Area of Morocco’s Gharb Plain Region. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, K.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Salicylic Acid Enhances Growth and Productivity in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. Capitata L.) Grown Under Saline Condition. Foc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chriqui, A.; Mouniane, Y.; Bensaid, A.; Soufiani, A.; Arabi, R.; Manhou, K.; Ameziane, H.; Benkhnigue, O.; Mabrouki, J.; Hmouni, D. Medicinal Flora of the Municipality Asjen of the Ouezzane Region, Morocco: A Comprehensive Look at the Biodiversity of Its Natural Resources—A Review. In Technical and Technological Solutions Towards a Sustainable Society and Circular Economy; Mabrouki, J., Mourade, A., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 567–579. ISBN 978-3-031-56291-4. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M.; Sanad, H.; Iben Halima, O.; Zouahri, A. Assessing the Evolution of Stability and Maturity in Co-Composting Sheep Manure with Green Waste Using Physico-Chemical and Biological Properties and Statistical Analyses: A Case Study of Botanique Garden in Rabat, Morocco. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, K.; Ahamed, K.U.; Islam, M.M.; Haque, M.N. Response of Tomato Plant Under Salt Stress: Role of Exogenous Calcium. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 10, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.R.; Choudhary, M.; Singh, J.; Lal, M.K.; Jha, P.K.; Udawat, P.; Gupta, N.K.; Rajput, V.D.; Garg, N.K.; Maheshwari, C.; et al. Impacts, Tolerance, Adaptation, and Mitigation of Heat Stress on Wheat under Changing Climates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Zouahri, A.; Sanad, H.; Saafadi, L.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M.; Mouhir, L. Sustainable Agriculture Through Agricultural Waste Management: A Comprehensive Review of Composting’s Impact on Soil Health in Moroccan Agricultural Ecosystems. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Jiang, C.; Tang, C.; Nie, X.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kang, Z.; et al. Wheat Adaptation to Environmental Stresses under Climate Change: Molecular Basis and Genetic Improvement. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1564–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.B.; Bauer, A.; Black, A.L. Effects of Air Temperature and Water Stress on Apex Development in Spring Wheat. Crop Sci. 1987, 27, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Saqib, M.; Rafique, Q.; Rahman, M.; Javaid, A.; Anwar-ul-Haq, M.; Nasim, M. Effect of Salinity on Grain Yield and Grain Quality of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Pak. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 50, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, S.A.; Zaman, M.; Heng, L. Introduction to Soil Salinity, Sodicity and Diagnostics Techniques. In Guideline for Salinity Assessment, Mitigation and Adaptation Using Nuclear and Related Techniques; Zaman, M., Shahid, S.A., Heng, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-3-319-96190-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sorour, S.G. Yield of Wheat Is Increased through Improving the Chemical Properties, Nutrient Availability and Water Productivity of Salt Affected Soils in the North Delta of Egypt. Appl. Ecol. Env. Res. 2019, 17, 8291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, S.; Munns, R.; Condon, A.G. (Tony) Effect of Sodium Exclusion Trait on Chlorophyll Retention and Growth of Durum Wheat in Saline Soil. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2003, 54, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; James, R.A.; Sirault, X.R.R.; Furbank, R.T.; Jones, H.G. New Phenotyping Methods for Screening Wheat and Barley for Beneficial Responses to Water Deficit. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3499–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, S.; Serret, M.D.; Araus, J.L. Shoot δ15N Gives a Better Indication than Ion Concentration or Δ13C of Genotypic Differences in the Response of Durum Wheat to Salinity. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattan, S.R.; Grieve, C.M. Salinity–Mineral Nutrient Relations in Horticultural Crops. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 78, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Granulometry | ||

| Sand | 13.1 | % |

| Silt | 34.3 | % |

| Clay | 52.6 | % |

| Chemical Properties | ||

| pH | 7.80 | - |

| EC | 0.20 | dS m−1 |

| OM | 1.33 | % |

| CEC | 0.65 | cmol kg−1 |

| Macronutrients | ||

| N | 0.078 | % |

| P | 120 | mg kg−1 |

| K | 229 | mg kg−1 |

| Na | 1.50 | mg kg−1 |

| Ca | 5.20 | mg kg−1 |

| Mg | 5.00 | mg kg−1 |

| Cl | 0.20 | mg kg−1 |

| Variety | Faraj | Nachit |

|---|---|---|

| Registration Year | 2007 | 2018 |

| Breeder/Origin | INRA, Morocco | INRA, Morocco |

| Agroecological Adaptation | Zones Bour favorable semi-arid areas | Zones Bour favorable semi-arid areas |

| Yield potential (t ha−1) | 5.9 (ZBF) 3.8 (ZSA) | 5.9 (ZBF) 4.1 (ZSA) |

| Key Quality Indicators | PC: 15.3% BQ: Good SQ: Good YI: 29 | PC: 15% BQ: Good SQ: Good YI: 27 |

| Drought Response | Moderate tolerance | Tolerant |

| Growth Duration (days) | 154 | 150 |

| Salinity (dS m−1) | Variety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nachit | Faraj | ||||

| GSI | MGT | GSI | MGT | ||

| 0.2 | 11.2 ± 0.14 a | 2.1 ± 0.05 a | 10.8 ± 0.11 a | 2.3 ± 0.06 a | |

| 4 | 9.5 ± 0.12 ab | 2.8 ± 0.07 ab | 8.9 ± 0.15 ab | 3.1 ± 0.08 ab | |

| 8 | 9.0 ± 0.13 ab | 3.7 ± 0.06 b | 8.4 ± 0.12 ab | 4.0 ± 0.05 b | |

| 12 | 4.2 ± 0.09 c | 5.5 ± 0.09 c | 3.7 ± 0.11 c | 5.9 ± 0.07 c | |

| 16 | 2.8 ± 0.08 d | 6.7 ± 0.08 d | 2.5 ± 0.09 d | 7.2 ± 0.09 d | |

| Variable Source | GSI | ||||

| Df | SS | MS | F | p-value | |

| Salinity (Sa) | 4 | 37.70 | 9.43 | 72.20 | <0.01 ** |

| Variety (V) | 1 | 3.40 | 3.50 | 26.90 | <0.01 ** |

| (S) × (V) | 4 | 1.10 | 0.27 | 2.20 | 0.09 ns |

| MGT | |||||

| Df | SS | MS | F | p-value | |

| Salinity (Sa) | 4 | 43.61 | 10.80 | 95.21 | <0.01 ** |

| Variety (V) | 1 | 5.10 | 5.10 | 44.52 | <0.01 ** |

| (S) × (V) | 4 | 1.30 | 0.35 | 3.01 | 0.06 ns |

| Salinity (dS m−1) | Variety | Grain Yield (t ha−1) | 200-Grain Weight (g) | Straw Yield (t ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | Faraj | 1.12 (1.80) | 67.0 (1.00) | 1.24 (1.00) |

| Nachit | 1.20 (1.60) | 69.5 (0.80) | 1.30 (0.90) | |

| 4 | Faraj | 0.70 (15.60) | 38.5 (7.60) | 1.18 (0.40) |

| Nachit | 0.85 (12.50) | 42.0 (6.50) | 1.25 (0.35) | |

| 8 | Faraj | 0.38 (15.60) | 34.6 (1.50) | 0.97 (0.10) |

| Nachit | 0.55 (12.00) | 37.5 (1.30) | 1.05 (0.09) | |

| 12 | Faraj | 0.18 (0.20) | 29.3 (1.50) | 0.80 (0.70) |

| Nachit | 0.28 (0.18) | 32.0 (1.10) | 0.90 (0.60) | |

| 16 | Faraj | 0.16 (0.10) | 11.6 (1.50) | 0.55 (0.30) |

| Nachit | 0.20 (0.08) | 15.0 (1.30) | 0.60 (0.25) | |

| 0.2 | 1.16 a | 68.25 a | 1.27 a | |

| 4 | 0.78 b | 40.25 b | 1.22 b | |

| 8 | Mean | 0.47 c | 36.05 c | 1.01 c |

| 12 | 0.23 d | 30.65 c | 0.85 c | |

| 16 | 0.18 d | 13.30 d | 0.58 d | |

| Yield Parameters | Grain Yield (t ha−1) | 200-Grain Weight (g) | Straw Yield (t ha−1) | |

| Variable Source | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | |

| Variety (V) | 0.023 * | 0.045 * | 0.062 ns | |

| Salinity (Sa) | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| V × Sa | 0.034 * | 0.041 * | 0.010 ** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manhou, K.; Moussadek, R.; Dakak, H.; Zouahri, A.; Ghanimi, A.; Sanad, H.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Hmouni, D. Effect of Irrigation with Saline Water on Germination, Physiology, Growth, and Yield of Durum Wheat Varieties on Silty Clay Soil. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222364

Manhou K, Moussadek R, Dakak H, Zouahri A, Ghanimi A, Sanad H, Oueld Lhaj M, Hmouni D. Effect of Irrigation with Saline Water on Germination, Physiology, Growth, and Yield of Durum Wheat Varieties on Silty Clay Soil. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222364

Chicago/Turabian StyleManhou, Khadija, Rachid Moussadek, Houria Dakak, Abdelmjid Zouahri, Ahmed Ghanimi, Hatim Sanad, Majda Oueld Lhaj, and Driss Hmouni. 2025. "Effect of Irrigation with Saline Water on Germination, Physiology, Growth, and Yield of Durum Wheat Varieties on Silty Clay Soil" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222364

APA StyleManhou, K., Moussadek, R., Dakak, H., Zouahri, A., Ghanimi, A., Sanad, H., Oueld Lhaj, M., & Hmouni, D. (2025). Effect of Irrigation with Saline Water on Germination, Physiology, Growth, and Yield of Durum Wheat Varieties on Silty Clay Soil. Agriculture, 15(22), 2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222364