Structural Characteristics and Phenolic Composition of Maize Pericarp and Their Relationship to Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. in Populations and Inbred Lines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

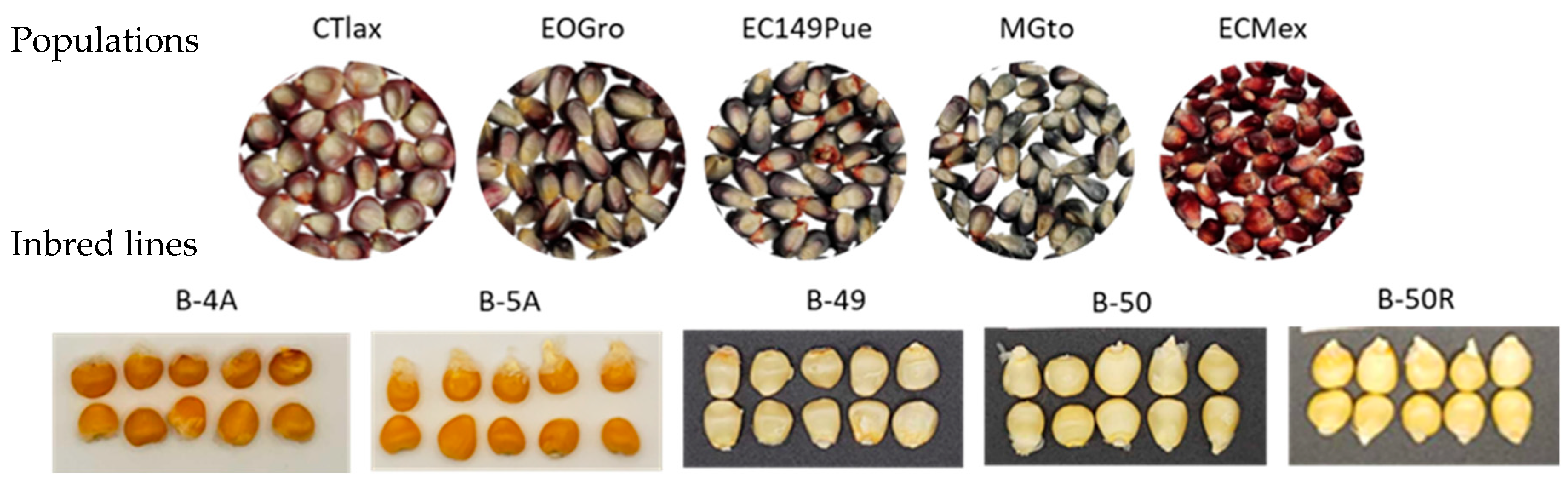

2.1. Genetic Materials

2.2. Evaluation of Native Maize Populations and Inbred Lines for Tolerance to Fusarium spp.

2.3. Pericarp Thickness in Maize Populations and Inbred Lines with Differential Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. Infection

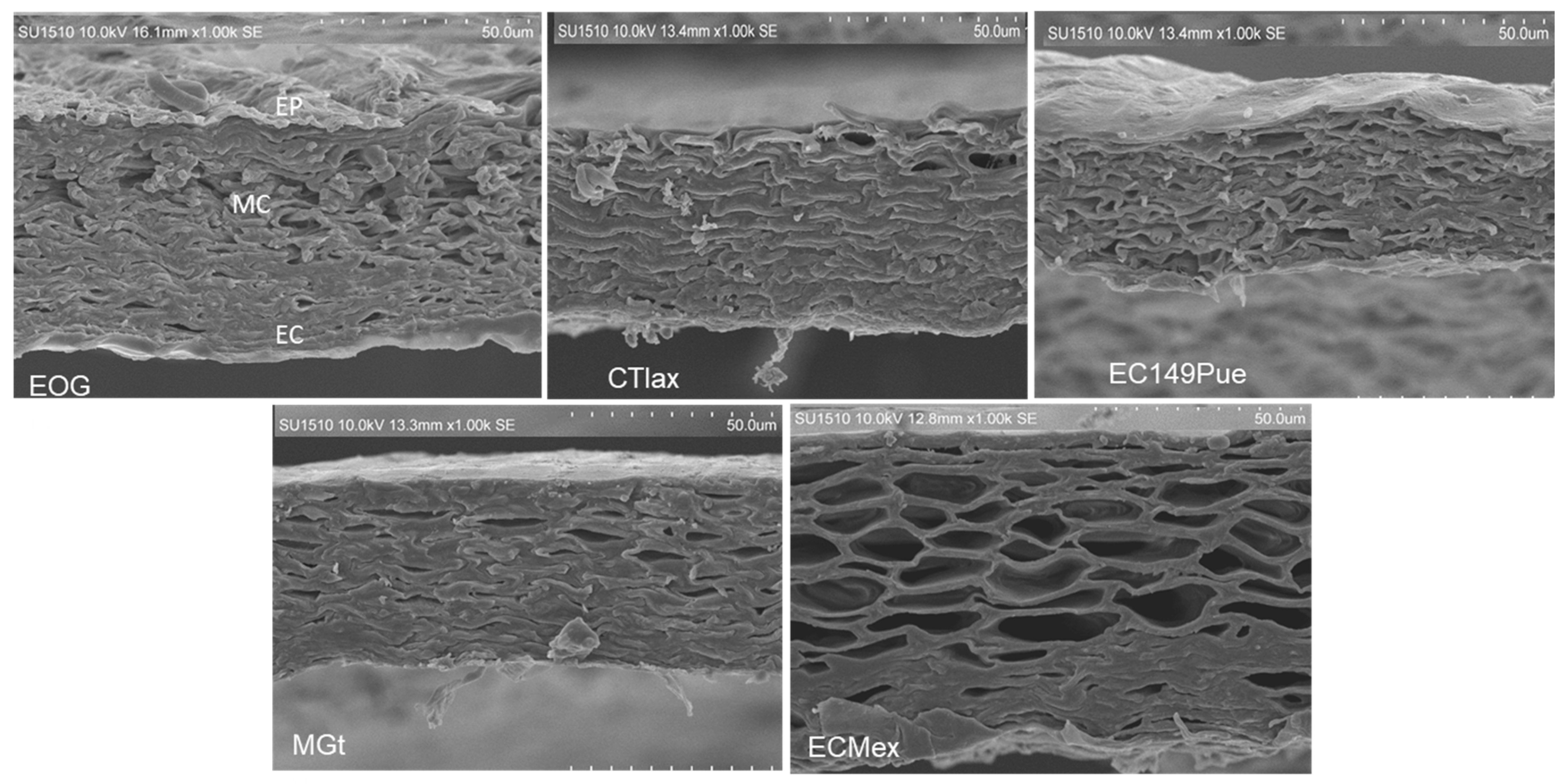

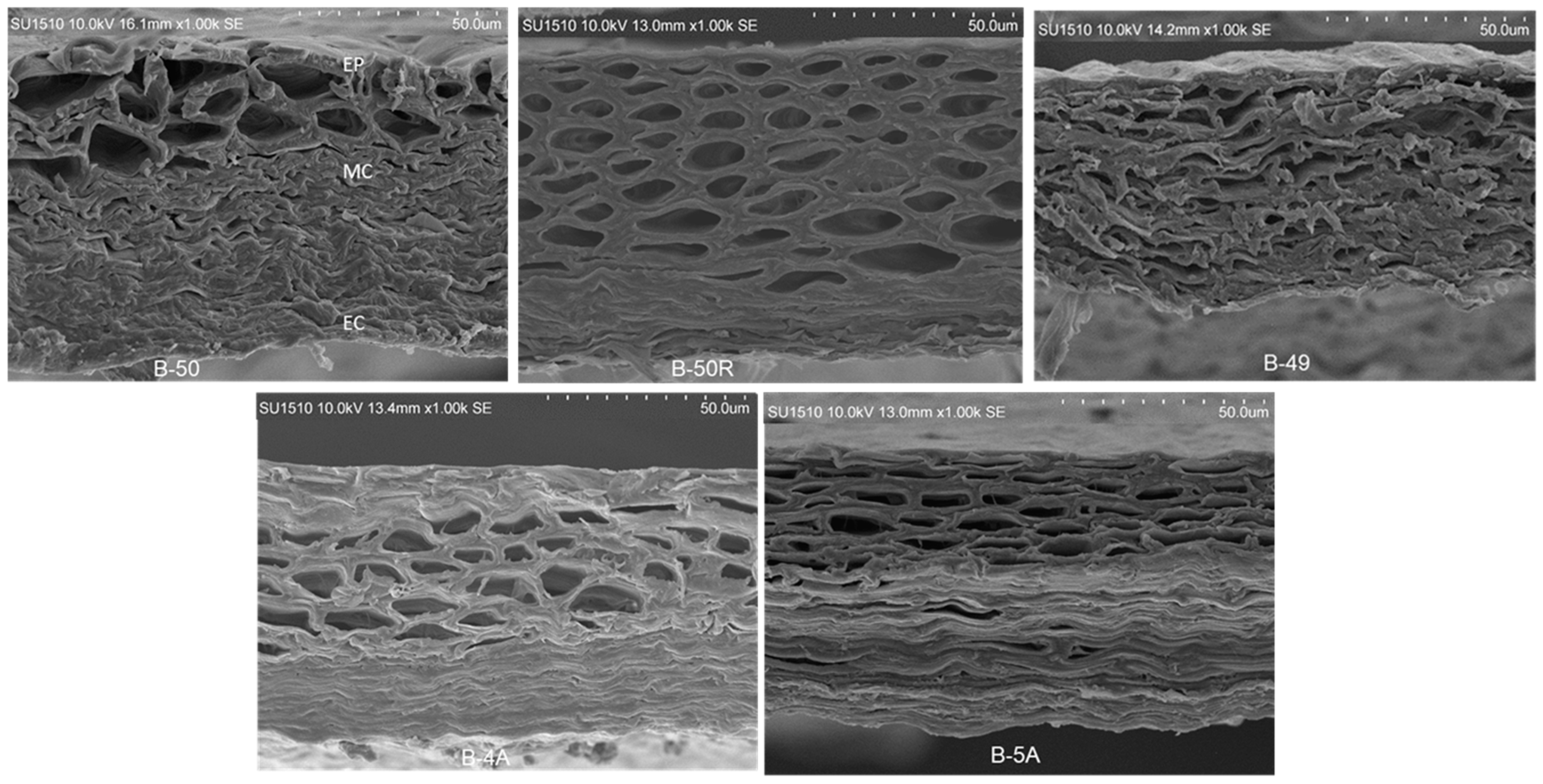

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Pericarps from Maize Populations and Inbred Lines with Differential Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. Infection

2.5. Phenolic Compounds in Grain and Pericarp of Maize Populations and Inbred Lines with Differential Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. Infection

2.5.1. Proanthocyanidins (PAs)

2.5.2. Soluble Phenolic Compounds (SPC)

2.5.3. Phenolic Acid Fractions

2.5.4. Insoluble Phenolics (IP)

2.5.5. Phlobaphenes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Incidence, Severity, and Pericarp Thickness in Maize Populations and Inbred Lines

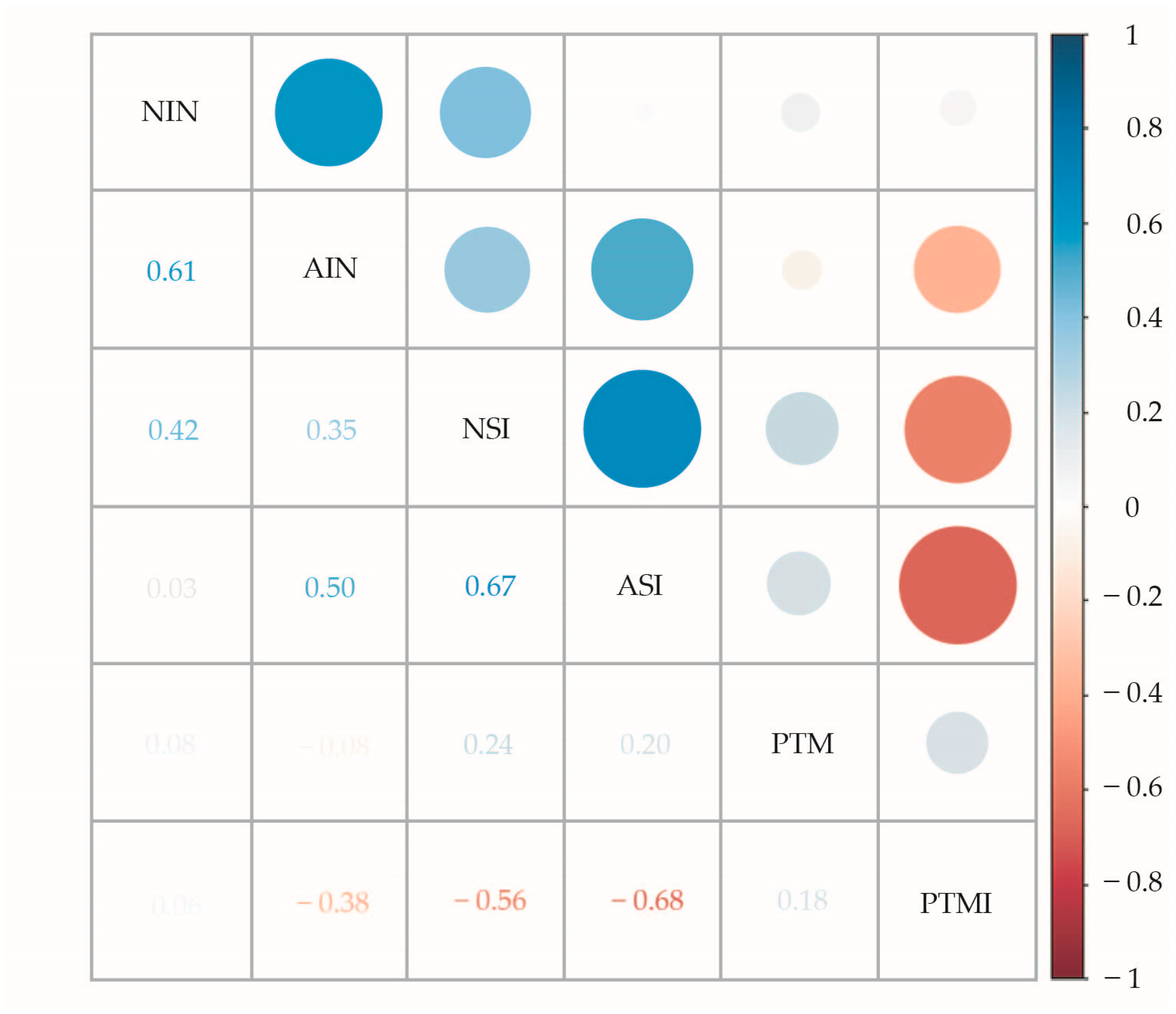

3.2. Relationship Between Pericarp Thickness and Infection Parameters

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Pericarps from Maize Populations and Lines with Different Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. Infection

3.4. Phenolic Compounds in the Pericarp of Maize Populations and Lines with Different Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. Infection

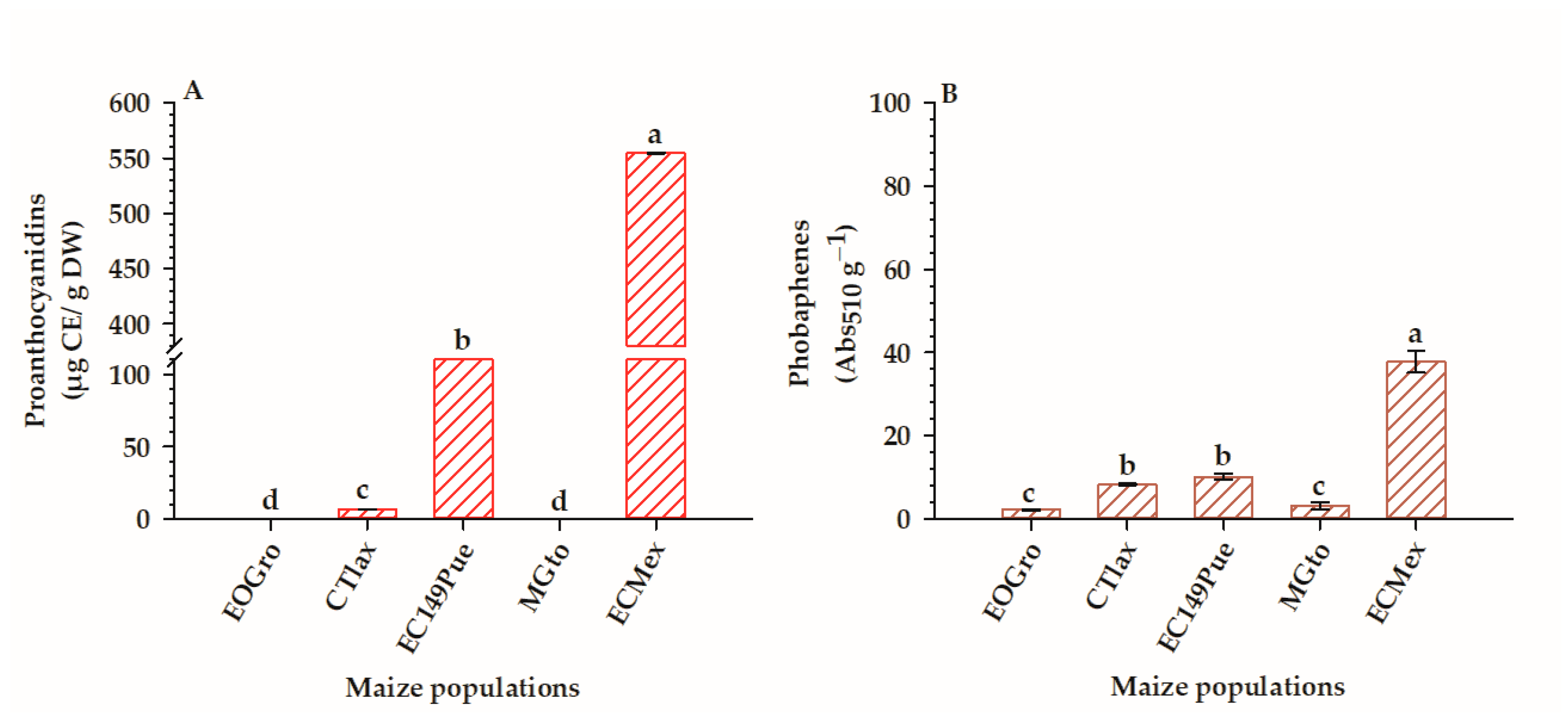

3.4.1. Populations

3.4.2. Inbred Lines

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPPG | Maize populations with pigmented grains |

| INIFAP | Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias |

| IL | Inbred lines |

| PAs | Proanthocyanidins |

| IN, % | Incidence |

| SI, % | Severity of infection |

| TSP | Total soluble phenolics |

| IP | Insoluble phenolics |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TSP | Total soluble phenols |

| FPA | Free phenolic acids |

| GPA | Glycosylated phenolic acids |

| EPA | Esterified phenolic acid |

| DW | Dry weight |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| PTM | Pericarp thickness measured with a Micrometer |

| PTMI | Pericarp thickness measured with scanning electron microscope |

| EP | Epicarp |

| MC | Mesocarp |

| EC | Endocarp |

| SDI | Severity of disease infection |

| MSD | Minimum significant difference |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: Trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R.; Cao, A.; Butrón, A. Genetic factors involved in fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels and their implications in maize agronomic management and breeding. Toxins 2015, 7, 3267–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giomi, G.M.; Sampietro, D.A.; Velazco, J.G.; Iglesias, J.; Fernández, M.; Oviedo, M.S.; Presello, D.A. Map overlapping of QTL for resistance to Fusarium ear rot and associated traits in maize. Euphytica 2021, 217, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, M.; Puglisi, D.; Cassani, E.; Borlini, G.; Brunoldi, G.; Comaschi, C.; Pilu, R. Phlobaphenes modify pericarp thickness in maize and accumulation of the fumonisin mycotoxins. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Fraca, J.; de la Torre-Hernández, M.E.; Meshoulam-Alamilla, M.; Plasencia, J. In search of resistance against fusarium ear rot: Ferulic acid contents in maize pericarp are associated with antifungal activity and inhibition of fumonisin production. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 852257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONABIO. Base de Datos del Proyecto Global “Recopilación, Generación, Actualización y Análisis de Información Acerca de la Diversidad Genética de Maíces y sus Parientes Silvestres en México”. 2017. Available online: https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/diversidad/proyectoMaices (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Santillán-Fernández, A.; de la Torre, I.A.; Ramírez-Díaz, J.L.; Ledesma-Miramontes, A.; Martínez-Ortiz, M.Á. Physical traits and phenolic compound diversity in maize with blue purple grain (Zea mays L.) of Mexican Races. Agriculture 2024, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilu, R.; Cassani, E.; Sirizzotti, A.; Petroni, K.; Tonelli, C. Effect of flavonoid pigments on the accumulation of fumonisin B1 in the maize kernel. J. Appl. Genet. 2011, 52, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianinetti, A.; Finocchiaro, F.; Maisenti, F.; Kouongni Satsap, D.; Morcia, C.; Ghizzoni, R.; Terzi, V. The caryopsis of red-grained rice has enhanced resistance to fungal attack. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trávníčková, M.; Chrpová, J.; Palicová, J.; Kozová, J.; Martinek, P.; Hnilička, F. Association between Fusarium head blight resistance and grain colour in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 52, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Meng, X.; Lin, X.; Duan, N.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Antifungal activity and inhibitory mechanisms of ferulic acid against the growth of Fusarium graminearum. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bily, A.C.; Reid, L.M.; Taylor, J.H.; Johnston, D.; Malouin, C.; Burt, A.J.; Bakan, B.; Regnault-Roger, C.; Pauls, K.P.; Arnason, J.T.; et al. Dehydrodimers of ferulic acid in maize grain pericarp and aleurone: Resistance factors to Fusarium graminearum. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buanafina, M.M.d.O.; Morris, P. The impact of cell wall feruloylation on plant growth, responses to environmental stress, plant pathogens and cell wall degradability. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Liu, L.; Cao, J.; Zhou, J.; Liu, E.; Li, R.; Ma, P.; Yao, W.; Wu, J. Enhancing maize resistance to Fusarium verticillioides through modulation of cell wall structure and components by ZmXYXT2. J. Adv. Res. 2025, S2090–1232, 00121–00123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacamo-Velázquez, N.Y.; Ireta-Moreno, J.; Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Gómez-Rodríguez, V.M.; Ramírez-Vega, H.; Martínez-Loperena, R. Variabilidad morfológica/patogénica de Fusarium verticillioides en la Ciénega/Chapala, México y evaluación de técnicas de inoculación. Agron. Mesoam. 2023, 34, 49679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, Á.; Lemmens, M.; Reid, L.M. Breeding for resistance to ear rots caused by Fusarium spp. in maize—A review. Plant Breed. 2012, 131, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. Three-dimensional structure determination of semi-transparent objects from holographic data. Opt. Commun. 1969, 1, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Evaluation of parameters that affect the 4-dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde assay for flavanols and proanthocyanidins. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C619–C625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Scott, P.; Domínguez-López, A. Total phenolic acids and hydroxycinnamates in the grain tissues of brown midrib (bm) maize mutants. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, B.; Bily, A.C.; Melcion, D.; Cahagnier, B.; Regnault-Roger, C.; Philogène, B.J.; Richard-Molard, D. Possible role of plant phenolics in the production of trichothecenes by Fusarium graminearum strains on different fractions of maize kernels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2826–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Reyes, D.; Castillo-González, F.; Chávez-Servia, J.L.; Aguilar-Rincón, V.H.; de León García-de Alba, C.; Ramírez-Hernández, A. Response of native maize from Mexican highlands to ear rot, under natural infection. Agron. Mesoam. 2015, 26, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pfordt, A.; Ramos Romero, L.; Schiwek, S.; Karlovsky, P.; von Tiedemann, A. Impact of environmental conditions and agronomic practices on the prevalence of Fusarium species associated with ear-and stalk rot in maize. Pathogens 2020, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, Y.-S. Pericarp thickness of Korean maize landraces. Plant Genet. Resour. 2019, 17, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez-González, E.D.; de Dios Figueroa-Cárdenas, J.; Taba, S.; Sánchez, F.R. Kernel microstructure of Latin American races of maize and their thermal and rheological properties. Cereal Chem. 2006, 83, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenisch, R.; Davis, R. Relationship between kernel pericarp thickness and susceptibility to Fusarium ear rot in field corn. Plant Dis. 1994, 78, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, T.; Kramer, A. Histological and histochemical studies of sweet corn (Zea mays L.) pericarp as influenced by maturity and processing. J. Food Sci. 1971, 36, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesselbach, T.; Walker, E.R. Structure of certain specialized tissue in the kernel of corn. Am. J. Bot. 1952, 39, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Reyes, R.; Rebellato, A.P.; Pallone, J.A.L.; Ferrari, R.A.; Clerici, M.T.P.S. Kernel characterization and starch morphology in five varieties of Peruvian Andean maize. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Jia, H.; Tang, Y.; Pei, H.; Zhai, L.; Huang, J. Genetic analysis and QTL mapping for pericarp thickness in maize (Zea mays L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chateigner-Boutin, A.-L.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J.; Alvarado, C.; Bouchet, B.; Durand, S.; Verhertbruggen, Y.; Barrière, Y.; Saulnier, L. Developing pericarp of maize: A model to study arabinoxylan synthesis and feruloylation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Somavat, P.; Singh, V.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Chemical characterization of proanthocyanidins in purple, blue, and red maize coproducts from different milling processes and their anti-inflammatory properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-C.; Tam, N.F.-y.; Lin, Y.-M.; Ding, Z.-H.; Chai, W.-M.; Wei, S.-D. Relationships between degree of polymerization and antioxidant activities: A study on proanthocyanidins from the leaves of a medicinal Mangrove plant Ceriops tagal. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, J.; Stagnati, L.; Lucini, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Lanubile, A.; Cortellini, C.; De Poli, G.; Busconi, M.; Marocco, A. Phenolic profile and susceptibility to Fusarium infection of pigmented maize cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, R.; Barros-Rios, J.; Malvar, R.A. Impact of cell wall composition on maize resistance to pests and diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6960–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic Material | Identity | NIN (%) | AIN (%) | NSI (%) | ASI (%) | PTM (µm) | PTMI (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Populations | EOGro | 26.25 b | 87.92 ab | 8.53 b | 33.61 ab | 70.13 de | 57.63 bcd |

| CTlax | 70.30 ab | 92.31 ab | 39.89 a | 48.93 a | 83.47 bc | 44.33 d | |

| EC149Pue | 19.70 b | 62.42 bc | 4.47 b | 15.25 c | 86.07 bc | 55.73 cd | |

| MGto | 66.67 ab | 66.67 abc | 21.28 ab | 16.84 bc | 80.53 c | 51.02 d | |

| ECMex | 39.77 b | 44.44 cd | 7.80 b | 6.65 c | 103.27 a | 66.68 abc | |

| Inbred lines | B-50 | 100.00 a | 100.00 a | 7.52 b | 6.79 c | 89.40 b | 70.67 ab |

| B-50R | 100.00 a | 94.84 ab | 5.47 b | 7.31 c | 64.20 e | 69.80 abc | |

| B-49 | 38.89 b | 66.67 abc | 2.40 b | 2.45 c | nd | 54.57 cd | |

| B-4A | 40.70 b | 40.14 cd | 1.69 b | 2.11 c | 71.53 d | 68.20 abc | |

| B-5A | 18.51 b | 17.21 d | 1.37 b | 1.95 c | 81.33 c | 74.80 a | |

| MSD | 54.97 | 33.60 | 20.48 | 17.45 | 6.01 | 15.56 |

| Maize | Phenolic Acids | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Populations | TSP | FPA | GPA | EPA | IP |

| EOGro | 1475.0 c | 761.1 c | 782.9 b | 710.9 a | 29,457.8 d |

| CTlax | 1580.3 c | 553.9 d | 359.5 c | 476.7 c | 39,451.3 a |

| EC149Pue | 10,119.1 b | 968.9 b | 599.3 b | 681.0 a | 29,513.9 d |

| MGto | 1294.1 c | 350.0 e | 275.0 c | 577.7 b | 31,851.0 c |

| ECMex | 28,191.6 a | 1592.4 a | 1354.0 a | 750.5 a | 34,920.3 b |

| MSD | 2952.9 | 198.0 | 212.9 | 87.6 | 1901.9 |

| Phenolic Acids | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inbred Lines | TSP | FPA | GPA | EPA | IP |

| B-50 | 1257.7 c | 617.8 b | 295.1 a | 444.3 a | 42,367.5 bc |

| B-50R | 1168.6 c | 436.9 b | 300.5 a | 280.4 b | 39,550.9 c |

| B-4A | 1449.5 b | 586.1 b | 234.9 b | 354.5 ab | 64,717.9 a |

| B-5A | 2035.9 a | 923.2 a | 254.9 ab | 318.7 ab | 45,922.1 b |

| MSD | 121.6 | 190.1 | 46.9 | 133.73 | 5094.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Zacamo-Velázquez, N.Y.; Mendoza-Garfias, M.B.; Ireta-Moreno, J.; Martínez-Ortiz, M.Á. Structural Characteristics and Phenolic Composition of Maize Pericarp and Their Relationship to Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. in Populations and Inbred Lines. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212240

Salinas-Moreno Y, Zacamo-Velázquez NY, Mendoza-Garfias MB, Ireta-Moreno J, Martínez-Ortiz MÁ. Structural Characteristics and Phenolic Composition of Maize Pericarp and Their Relationship to Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. in Populations and Inbred Lines. Agriculture. 2025; 15(21):2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212240

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalinas-Moreno, Yolanda, Norma Y. Zacamo-Velázquez, María Berenit Mendoza-Garfias, Javier Ireta-Moreno, and Miguel Ángel Martínez-Ortiz. 2025. "Structural Characteristics and Phenolic Composition of Maize Pericarp and Their Relationship to Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. in Populations and Inbred Lines" Agriculture 15, no. 21: 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212240

APA StyleSalinas-Moreno, Y., Zacamo-Velázquez, N. Y., Mendoza-Garfias, M. B., Ireta-Moreno, J., & Martínez-Ortiz, M. Á. (2025). Structural Characteristics and Phenolic Composition of Maize Pericarp and Their Relationship to Susceptibility to Fusarium spp. in Populations and Inbred Lines. Agriculture, 15(21), 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212240