1. Introduction

Maize is one of the important food crops with its characteristics of high production and easy cultivation, which have become an important source of food, fodder, and industrial raw material. The purity of maize seed is an important indicator to evaluate the quality of the maize seed. In the ways of improving the purity of maize seed, the most important part is maize detasseling. China’s maize seed production field area is about 2.3 million hectares, so the detasseling operation is very important [

1,

2]. Usually, in maize fields, the father parent and the mother parent of the maize are usually planted in a certain ratio, usually 1:3 to 6, in order to achieve higher yields [

3,

4]. The male flowers of the mother parent need to be detasseled, while the male flowers of the father parent do not need to be detasseled. At present, the detasseling operation of maize in China is dominated by manual labor, which has high labor intensity, high cost, and low efficiency. The operation conditions of manual labor are harsh and easily affected by weather changes. Mechanical equipment has high operation efficiency and is less affected by natural conditions, so it has been given more and more attention in maize seed production.

However, the existing maize detasseling equipment is not suitable for the detasseling operation requirements in maize seed production fields. This is mainly due to the non-uniform distribution of male flowers in maize seed production fields and the agronomic requirement for timely detasseling. Due to the non-uniform distribution of sunlight, water, and fertilizer across the field, the time of male flower in maize plants varies across different areas [

5,

6]. In seed production fields, to prevent pollen from the father parent from compromising seed purity, the detasseling operation must be carried out promptly once the male flowers of the father parent begin to emerge. For such small-scale, frequent, and precise detasseling tasks, if the existing maize detasseling equipment is still used for full coverage operations, it will lead to unnecessary increases in operation costs and time, as well as excessive soil compaction.

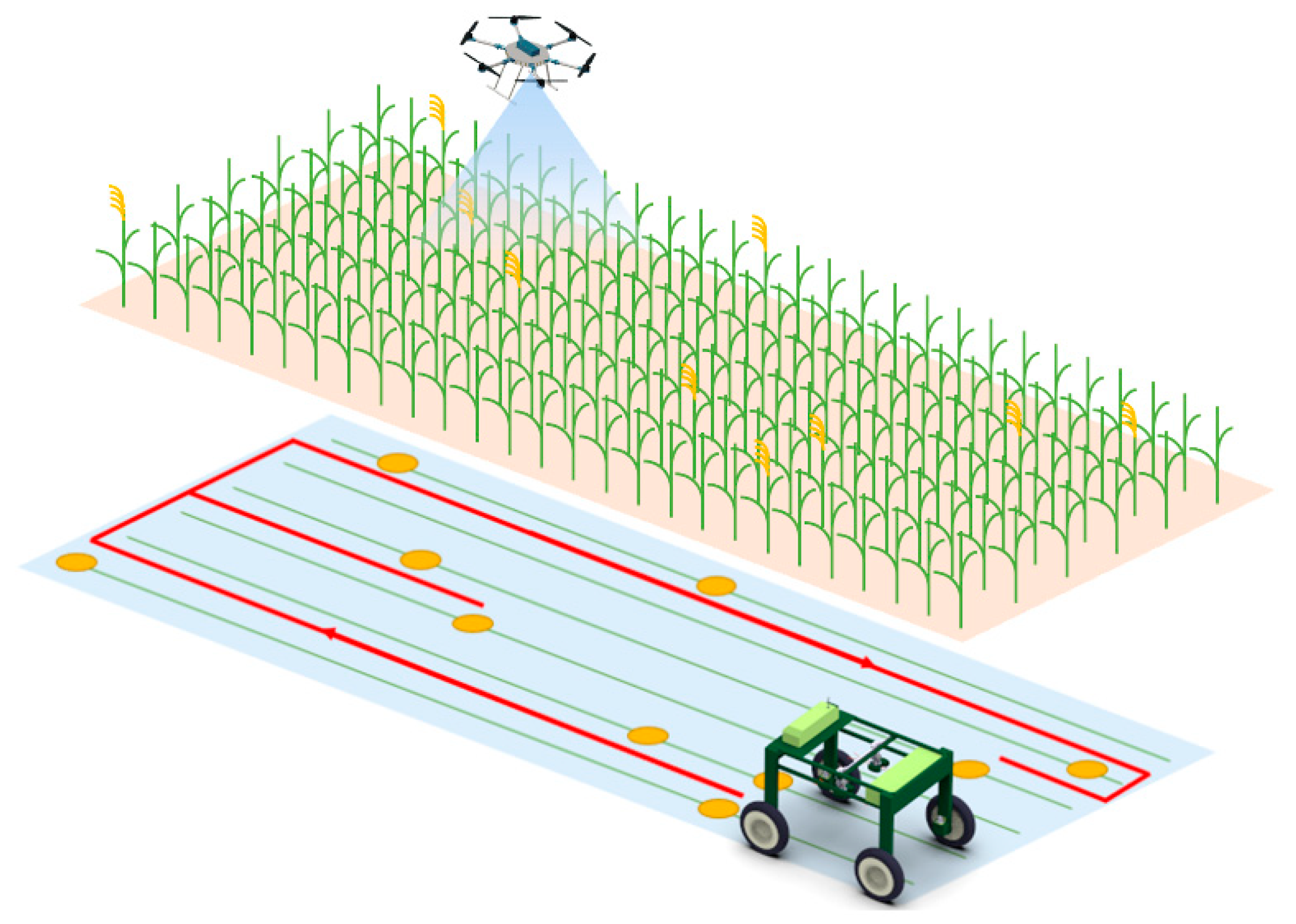

With the continuous improvement of the automation and intelligence levels of agricultural machinery, some lightweight and small unmanned maize detasseling equipment (referred to as UDV), which are more suitable for the requirements of detasseling operations in maize seed production fields, have gradually emerged. Maize detasseling robots developed by institutions such as China Agricultural University and Jiuyu Technology Company are capable of accurately identifying and removing maize male flowers [

7]. Furthermore, a variety of related technologies have been introduced, offering technical support to enhance the efficiency of detasseling operations. For example, the intelligent detasseling detection system developed establishes a detection platform based on advanced image recognition technology [

8,

9,

10]. This system not only substantially reduces the cost and workload associated with manual detection but also provides critical data for the planning of detasseling operation routes. UDV is currently in its early stage of development. The level of automation and intelligence under unmanned driving conditions remains a significant constraint on the improvement of its operational efficiency. Therefore, investigating a route planning method tailored for UDV has become an urgent priority.

Since the 1960s, for solving the problems of route planning, researchers have done lots of work to advance the approaches and applications [

11,

12]. The route planning problems belong to the category of optimization, and optimization for all disciplines is essential and relevant. With the development of artificial intelligence, more and more intelligent algorithms are widely used in the field of route planning, mainly including Maze Algorithm, Network Algorithm, Genetic Algorithm (GA), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), etc. Ritam Sarkar et al. proposed a domain knowledge-based genetic algorithm for mobile robot path planning having single and multiple targets, and set up four operators [

13]. X. Liu et al. proposed a multi-mechanism collaborative improved grey wolf optimization algorithm (NAS-GWO) for agricultural UAV trajectory planning. It introduces an evolutionary boundary constraint processing mechanism to enhance search accuracy, uses Gaussian mutation and spiral functions to avoid local optima, and applies an improved Sigmoid function for balance [

14]. Y. Volkan Pehlivanoglu et al. proposed an enhanced genetic algorithm for path planning of autonomous UAVs in target coverage problems, which can map out a reasonable path [

15]. Guo Hui et al. proposed an optimal search path planning for unmanned surface vehicles based on an improved genetic algorithm [

16]. Mohamed Amine Yakoubi et al. proposed a path planning of cleaner robots for coverage region using Genetic Algorithms [

17]. Chaymaa Lamini et al. proposed a Genetic Algorithm based on autonomous mobile robot path planning, improving the shortcoming of premature convergence [

18]. Baoye Song et al. proposed an improved PSO algorithm for smooth path planning of mobile robots using a continuous high-degree Bezier curve. In this paper, the advantages of the new strategy are also confirmed by simulation experiments for the smooth path planning of mobile robots [

19]. Xinghai Guo et al. proposed a global path planning and multi-objective path control for unmanned surface vehicles based on modified particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm, it can plan a reasonable path [

20]. Fatin H. Ajeil et al. proposed a multi-objective path planning of an autonomous mobile robot using a hybrid PSO-MFB optimization algorithm [

21]. Yang Liu et al. proposed collision-free 4D path planning for multiple UAVs based on spatial refined voting mechanism and PSO approach [

22]. Girija et al. proposed a fast Hybrid PSO-APF Algorithm for Path Planning in Obstacle Rich Environment [

23]. Rui Oliveira et al. proposed Optimization-Based On-Road Path Planning for Articulated Vehicles, which can evaluate and analyze in simulations on a set of complicated and practically relevant on-road planning scenes [

24]. P.K. Das et al. proposed a multi-robot path planning using an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm through novel evolutionary operators; it can navigate the robots in the shortest path and use minimum energy, and avoid deadlock situations [

25]. Michael Borish et al. proposed a GPU-based approach for path planning optimization through travel length reduction. This representation was then utilized by the GPU to solve the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) [

26].

Compared with other algorithms, ACO has several advantages, including high parallelism, self-organization, good robustness, strong positive feedback capability of pheromones, ease of combination with different algorithms, and so on. According to the inherited characteristics of natural ant colonies, the ACO algorithm is more suitable for solving the path planning problem. Current research demonstrates the good performance of ACO, particularly in various industrial applications. To address the limitations of the traditional Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm in solving mobile robot path planning problems, such as slow convergence speed, inefficiency, and easily falling into local optimal values, Wu et al. proposed a modified adaptive ant colony optimization algorithm (MAACO). By designing a novel heuristic mechanism with orientation information, an improved heuristic function, a state transition probability rule, and an unevenly distributed initial pheromone, this algorithm substantially enhances both convergence speed and search efficiency [

27]. Cui et al. proposed a multi-strategy adaptable ACO (MsAACO), which integrates four novel mechanisms: direction recognition for node selection, an adaptive heuristic function for reducing path length and turns, deterministic state transition rules for accelerating convergence, and non-uniform pheromone initialization for exploring favorable regions. MsAACO has more advantages in generating smoother optimal paths with shorter lengths and fewer turns [

28]. An improved dynamic adaptive ACO (IDAACO) was proposed by Liu et al. IDAACO includes four new mechanisms, namely heuristic strategies with directional information, adaptive pseudorandom transfer strategy, improved local pheromone updating mechanisms, and improved global pheromone updating mechanisms, which experimentally confirm IDAACO’s advantages in utility and high efficiency [

29]. An improved adaptive ant colony optimization (IAACO) was proposed by Miao et al. In IAACO, first of all, in order to speed up the real-time and security of robot path planning, they introduce angle guidance factor and obstacle exclusion factor in ACO transmission probability, solve the traditional ant colony optimization (ACO) in indoor mobile robot path planning, slow convergence of nonoptimal paths, and ACO local optimal solution characteristics [

30]. Wang et al. proposed mobile robot path planning based on parameter-optimized ant colony algorithm, the simulation results demonstrate that the improved algorithm achieves significantly shorter optimal path length compared to the basic ant colony algorithm, with reduced fluctuations and significantly enhanced stability [

31]. Zhang et al. propose an improved adaptive Ant Colony algorithm (IAACO). This algorithm incorporates risk, energy consumption, and route length into multi-objective constraints, optimizes the heuristic function and pheromone update mechanism, and introduces an adaptive volatility coefficient to balance convergence and global search ability [

32].

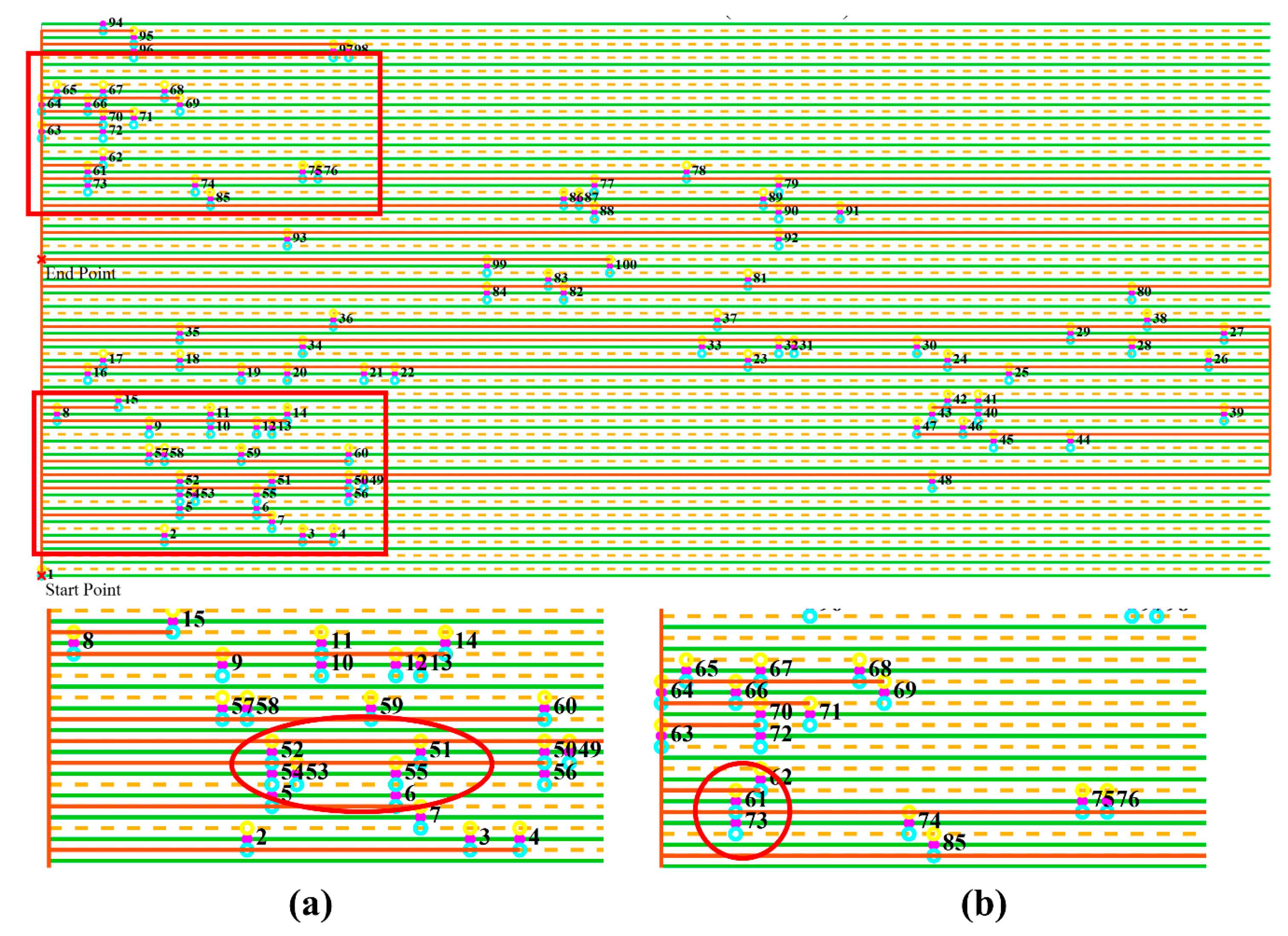

The detasseling route planning problem in maize seed production fields is analogous to the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), requiring routes to traverse all male flowers within the shortest operational distance. At present, there is a lot of literature on TSP. Fa Wei Ge et al. proposed a Path planning of UAV for oilfield inspections in a three-dimensional dynamic environment with moving obstacles based on an improved pigeon-inspired optimization algorithm. This method can solve the problem of node traversal path planning in the three-dimensional environment [

33]. Shubhra Sankar Ray et al. proposed some Genetic operators for combinatorial optimization in TSP and microarray gene ordering. These result in faster convergence of the Genetic Algorithm in finding the optimal order of genes in microarray and cities in TSP [

34]. Veronika Lesch et al. proposed incorporating the main relevant real-world constraints and requirements. They proposed a two-stage strategy and a Timeline algorithm for time windows and pause times, and applied a Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO). Experimental results show that the path planning method can obtain a reasonable route [

35]. Anubha Agrawal et al. proposed an evolutionary algorithm hybridized with local search and intelligent seeding for solving multi-objective Euclidean TSP, the problems having objectives up to four and several cities up to 10,000 are solved [

36]. Aiming at the main challenges of high geometric complexity search space and local solution traps in the travel agent UAV Cooperative Problem (TSP-D), Yılmaz et al. propose an evolutionary algorithm based on fitness distance balance (FDB-EA), adopting guided selection methods based on greed, randomness, and FDB scores. These methods are mixed at different rates to form strategies with diverse search capabilities, and the mixed strategies are associated with different search stages to achieve dynamic behaviors, thereby maintaining a sustainable balance between development and exploration [

37].

In agricultural applications, the TSP holds significant importance. Liang et al. proposed an Improved Whale Optimized Ant Colony Optimization for the multi-node traversal problem of electric tractors. By incorporating a reverse learning strategy, a nonlinear convergence factor, and an adaptive inertia weight factor, this algorithm effectively enhances both global and local convergence capabilities, thereby improving the operational efficiency and endurance of electric tractors [

38]. Cerdeira-Pena et al. investigated a variant of the TSP with additional constraints, employing Tabu Search and Simulated Annealing to optimize the operational paths of multiple harvesters [

39]. Cariou et al. addressed path planning for mobile robots in pasture maintenance by clustering path information data using approximation algorithms, converting it into a TSP, and solving it with evolutionary algorithms [

40]. The mentioned studies proposed corresponding solutions for heterogeneous TSP arising from multi-node traversal in different agricultural environments. However, unlike the multi-node traversal problem in maize detasseling operations, nodes in these scenarios are not constrained within crop rows and exhibit significant spatial variation in their distribution.

It can be seen from the above literature that no researcher has studied the detasseling route planning problem at present. The current research method of TSP is not applicable to the model in this paper, because the model contains constraints for UDV to drive on maize seed production fields. Because the route planning problem in maize seed production fields is significantly different from the traditional TSP. The route planning problem for maize detasseling operations, from the perspective of traversing plants between different crop rows, presents a two-dimensional discrete distribution characteristic. However, from the perspective of visiting plants within a crop row, it has a one-dimensional linear feature, which makes this problem have hybrid spatial constraints. Meanwhile, the topological structure of this problem differs from the traditional TSP in that the nodes are not connected by a single route.

Because the route planning problem in maize seed production fields is significantly different from the traditional TSP. The route planning problem for maize detasseling operations, from the perspective of traversing plants between different crop rows, presents a two-dimensional discrete distribution characteristic. However, from the perspective of visiting plants within a crop row, it has a one-dimensional linear feature, which makes this problem have hybrid spatial constraints. Meanwhile, the topological structure of this problem differs from the traditional TSP in that the nodes are not connected by a single route. Several viable connection methods exist between any two male flower nodes, resulting in an exponential increase in the complexity of the solution space.

This paper proposes a multi-mechanism coupled DRDM-AACO (Dual-Route and Dual-Mode Adaptive Ant Colony Optimization) to solve the detasseling route planning problem for UDV, considering hybrid spatial constraints from a heterogeneous TSP variant. This variant involves both one-dimensional and two-dimensional hybrid Spatial-Constrained features, as well as complex topological structures.

The main contributions are as follows:

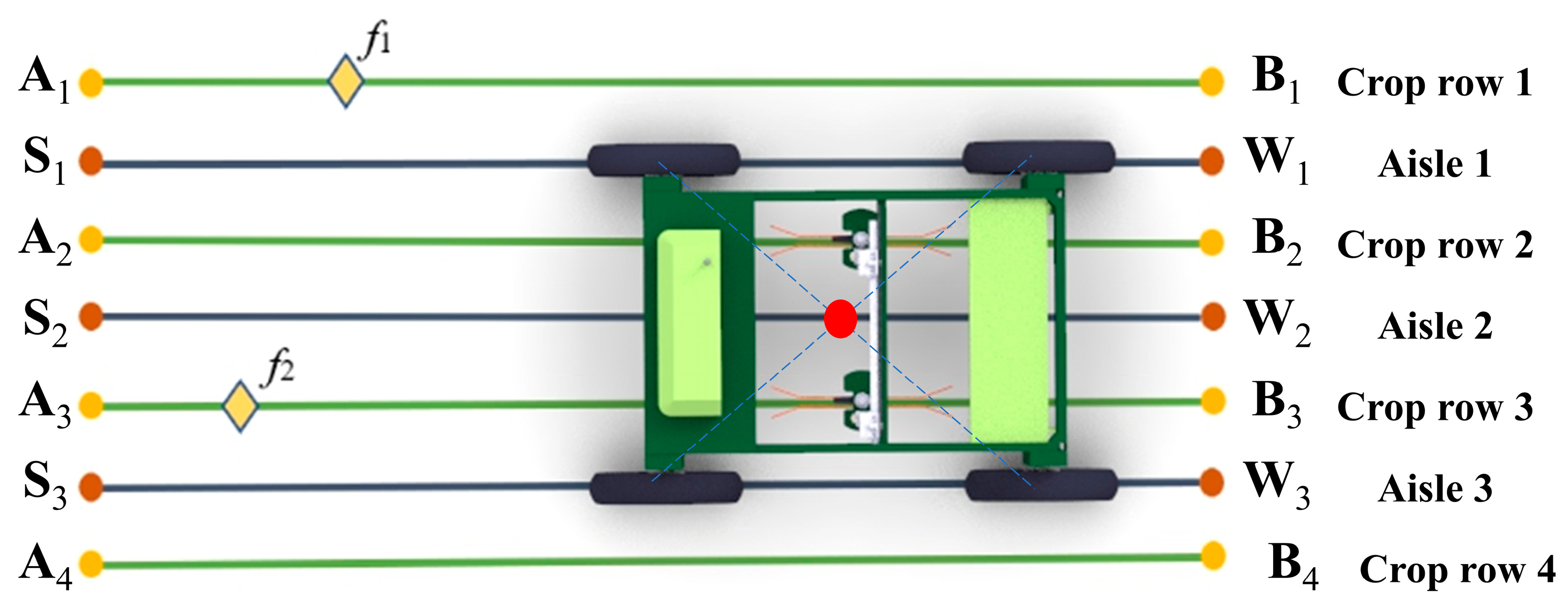

Establish a mathematical model to optimize the detasseling operation routes in maize seed production fields. The model proposes a method to establish the projection nodes of the male flower nodes on different aisles to adapt to the characteristics of the UDV double-row operation width in the text. Meanwhile, a multi-dimensional distance matrix was constructed from the projection nodes and used as input for DRDM-AACO. The model outputs the detasseling sequence and the approach to the male flower node, with the objective of minimizing detasseling route length.

Based on the traditional ACO, four improvement mechanisms were proposed. The dual-route preference mechanism enhances the global optimization capability through a dynamic selection strategy of the main and auxiliary routes. The dynamic candidate set mechanism adopts variable neighborhood search to achieve a balance between exploration and exploitation. The non-uniform initial pheromone allocation mechanism follows the principle of intra-row priority and inter-row inhibition, effectively guiding the generation of routes. The direction-constrained adaptive dual-mode pheromone regulation mechanism avoids generating intra-row turnback routes through local punishment and global evaporation strategies.

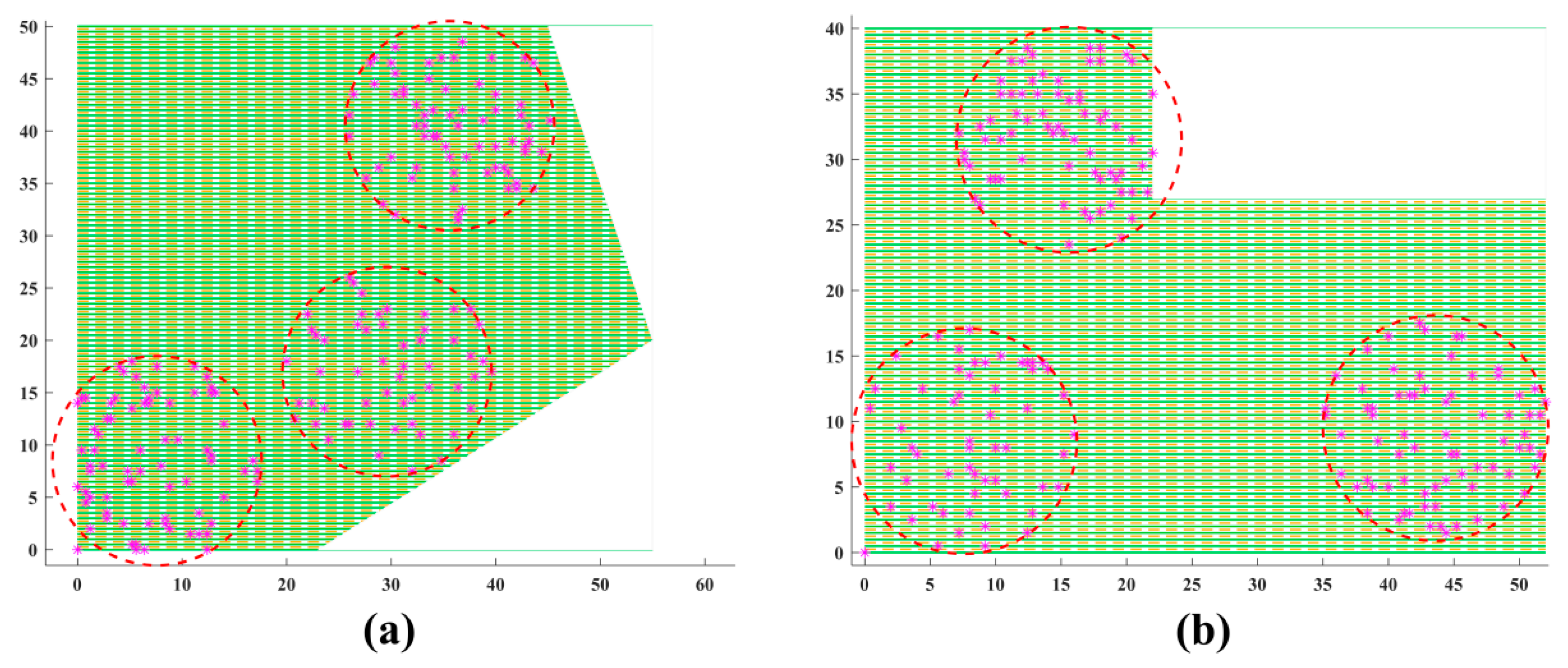

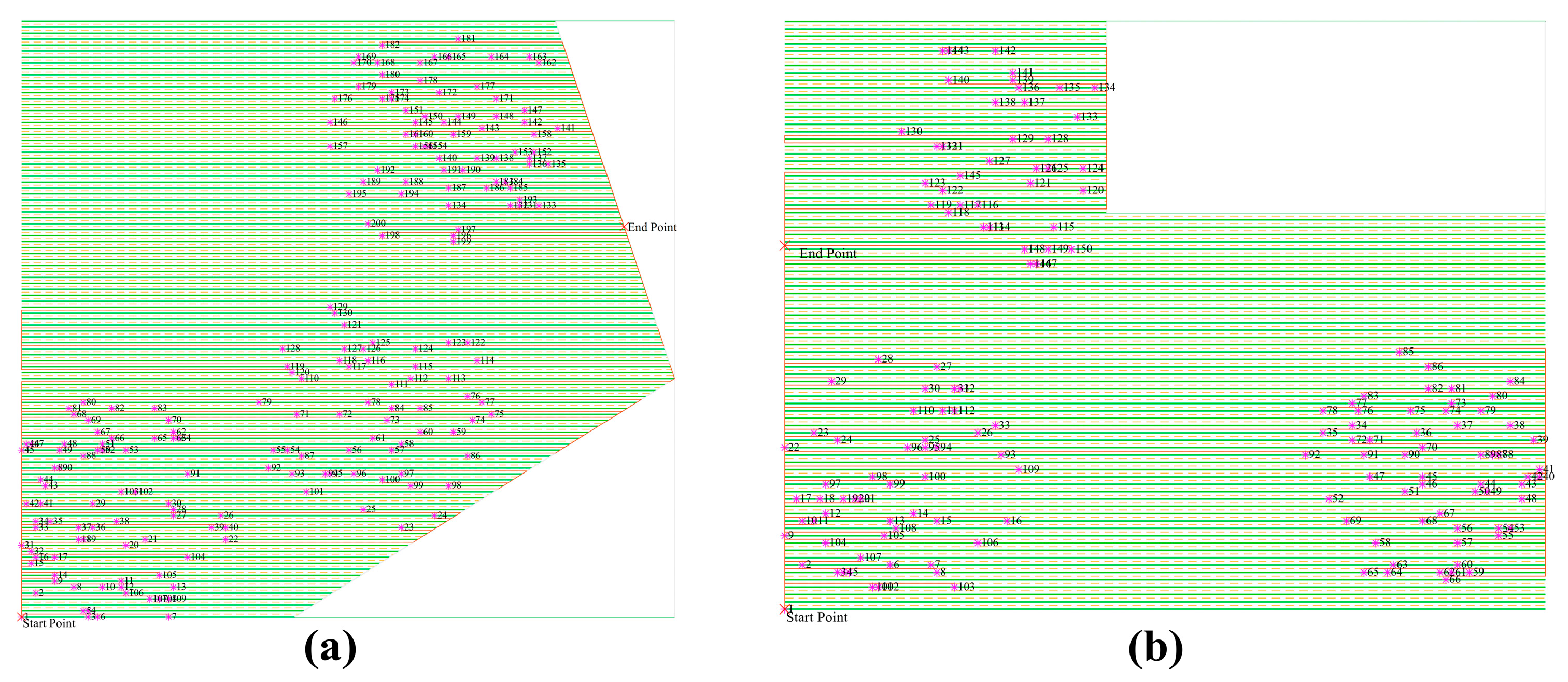

A multi-step simulation experiment was designed. Through comparative experiments with ACO and its variants, the effectiveness of various mechanisms of DRDM-AACO was verified. A simulation experiment of actual field operation was conducted to confirm its practicality and superiority in fields of different sizes and boundary shapes.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the mathematical model, including the field establishment model and the route establishment model.

Section 3 presents the four mechanisms proposed in DRDM-AACO in detail.

Section 4 presents the effectiveness analysis of various mechanisms and the analysis of experiments from actual field simulations.

Section 5 summarizes the paper and outlines future research directions.

3. The Proposed DRDM-AACO

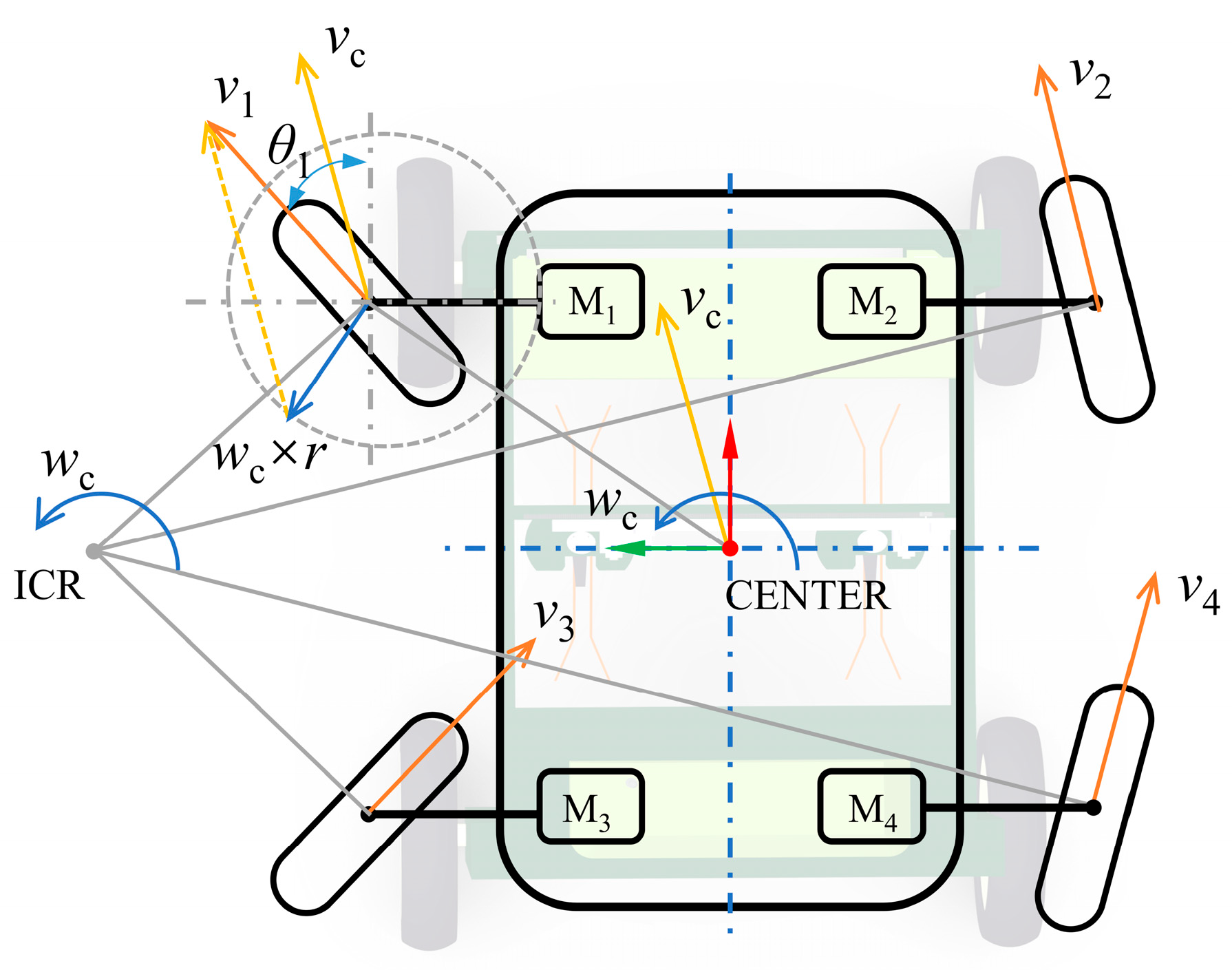

In this paper, ACO is used to deal with the route planning problem due to its applicability to the TSP. However, the traditional ACO algorithm only takes into account the Euclidean distance of a single route between nodes. In contrast, in real farmland environments, multiple feasible routes exist between male flower nodes, which are constrained by crop rows. In addition, the distribution of male flower nodes in the field has a hybrid spatial characteristic, including a two-dimensional distribution across different crop rows and a one-dimensional distribution along the same crop row. Moreover, the UDV has detailed requirements, such as a double-row working width, which further complicates the issue. Therefore, traditional ACO must be improved to solve this heterogeneous TSP with hybrid space constraints. In response to the above issues, four mechanisms are proposed in the following text.

3.1. Dual-Route Preference Mechanism

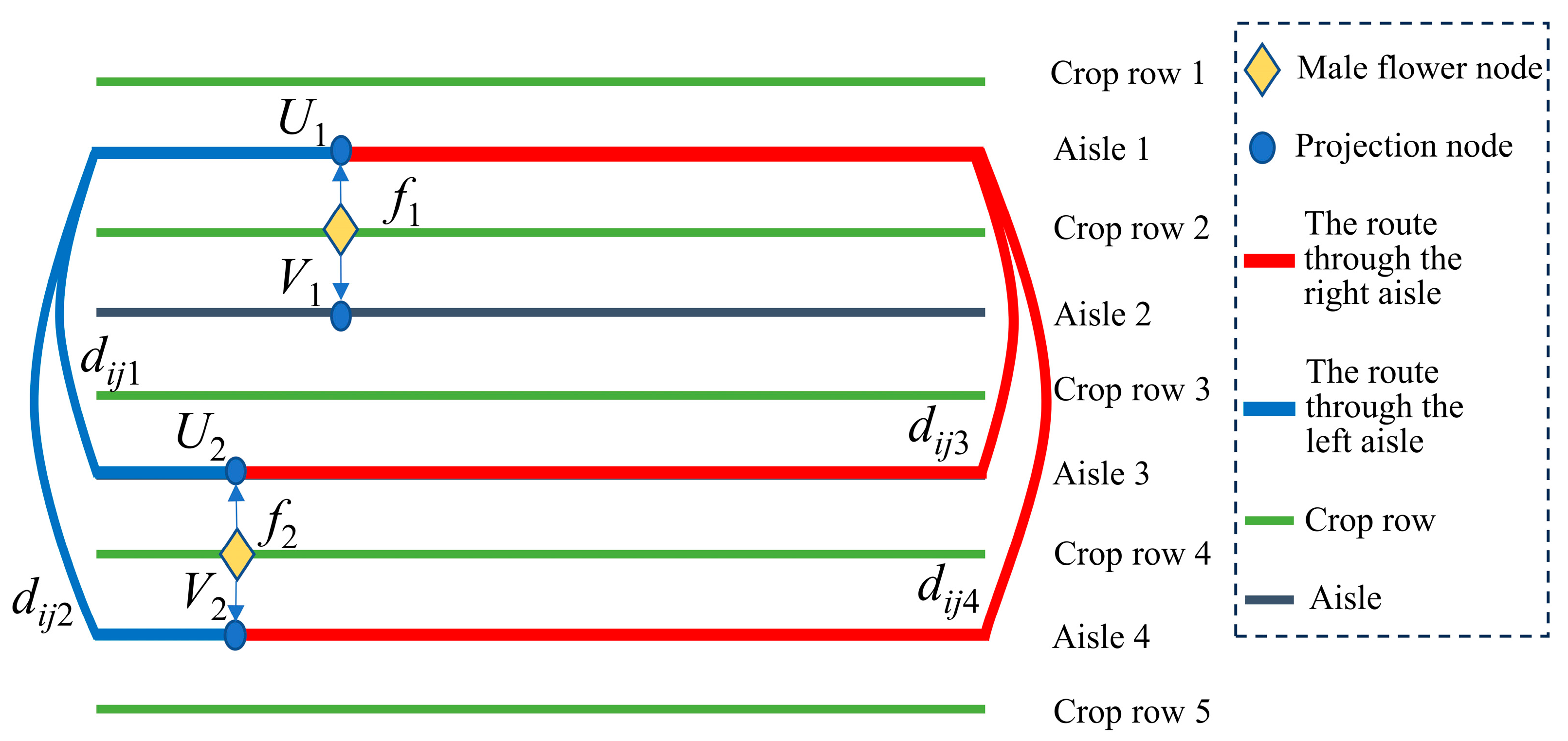

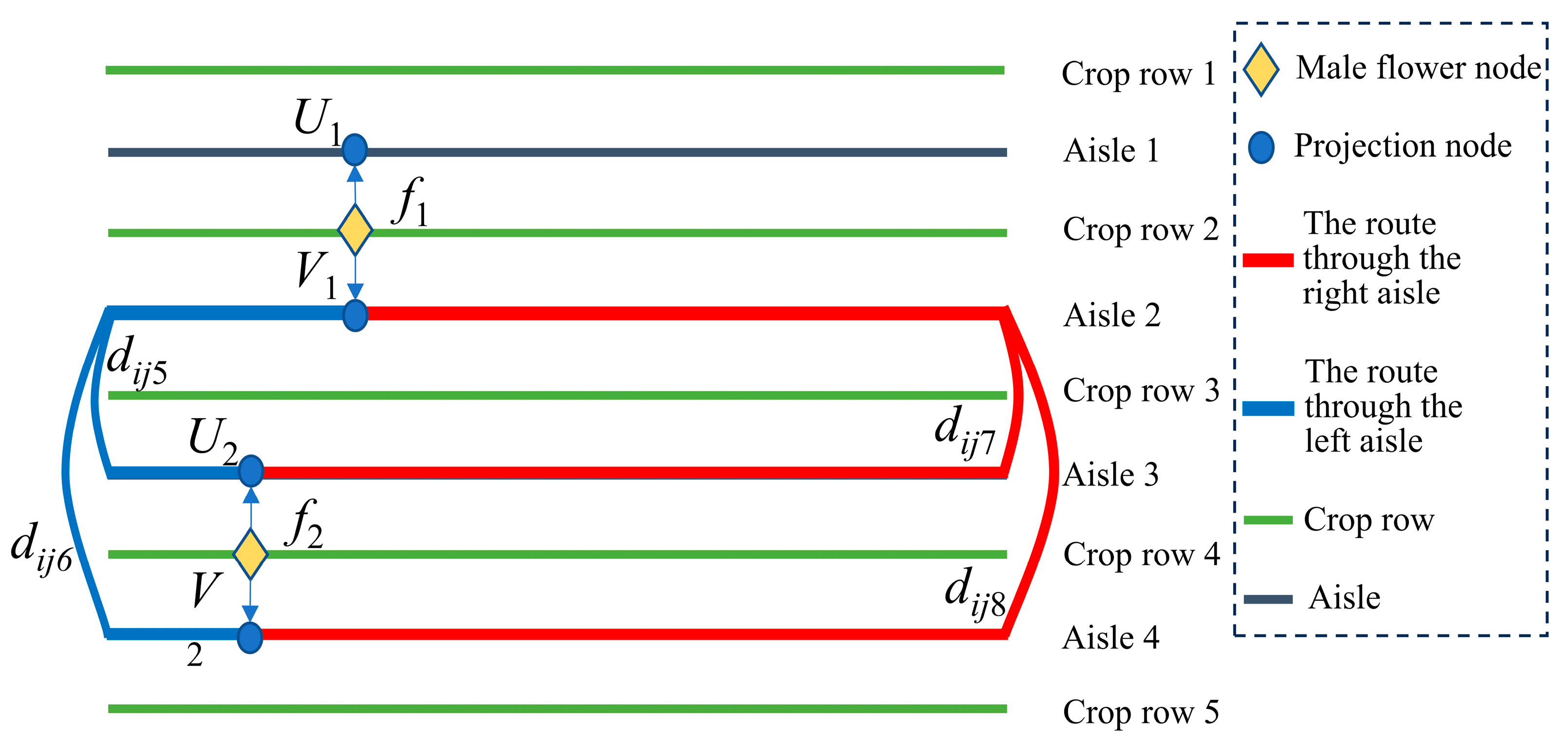

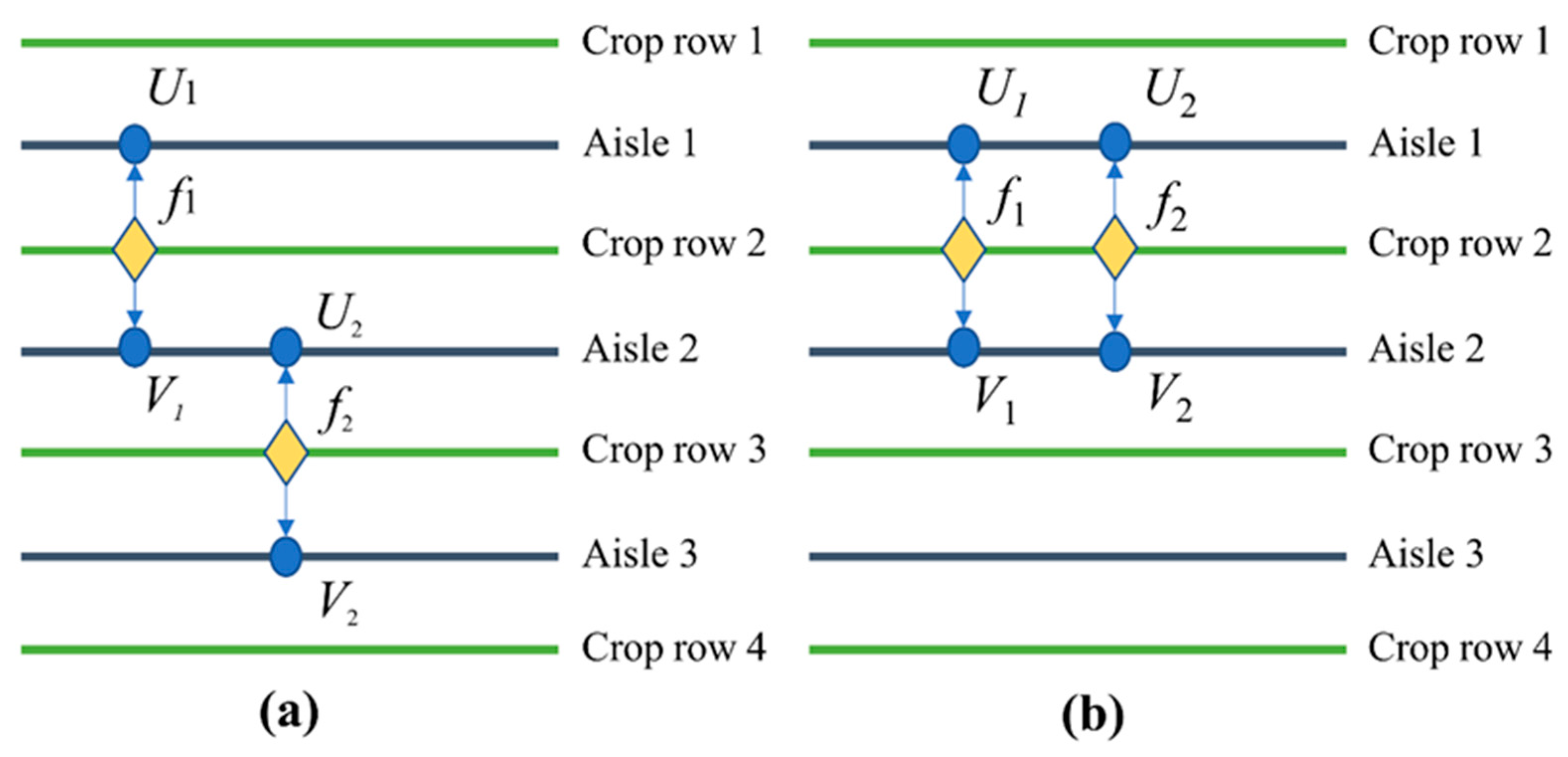

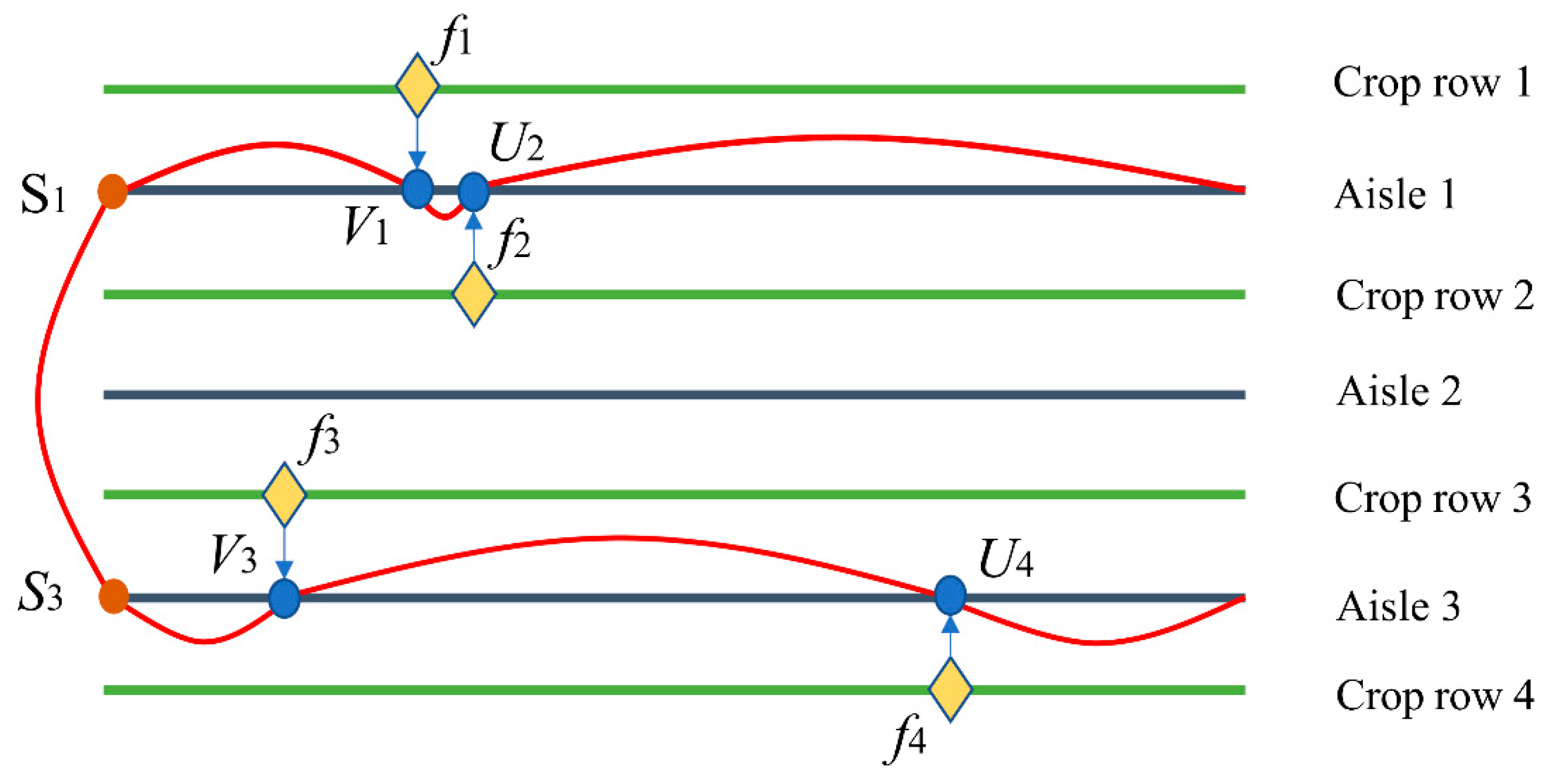

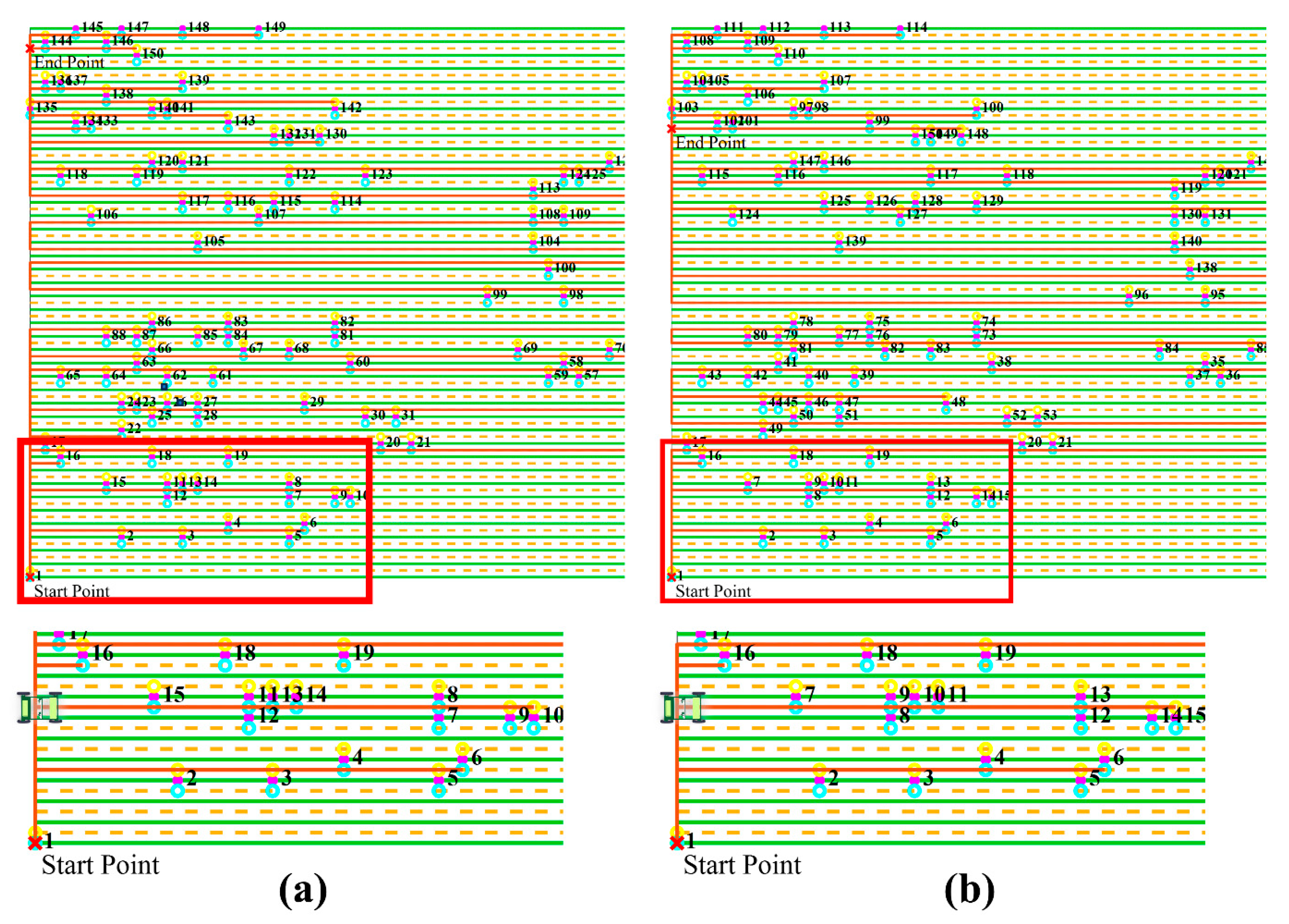

There are eight routes between each pair of male flower nodes, requiring eight distance matrices. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, there are eight possible routes between male flowers

fi and

fj. In the selection results, only changes in

Uj and

Vj will influence subsequent route selection, thereby impacting the overall routing outcome.

Therefore, to simplify the calculation, only the shortest routes to the projection nodes Uj and Vj of fj are retained. Among them, the shorter route is named the main route, and the other one is named the auxiliary route. The dual-route preference mechanism involves the establishment of heuristic information and the establishment of a dual-route collaborative probability decision model.

3.1.1. Heuristic Information of the Dual-Route Preference Mechanism

Heuristic information is related to the distance matrix and will affect the selection probability. In traditional ACO, there is only one route between the current node and the target node, so there is only one heuristic information.

Based on the dual-route preference mechanism, when the UDV is positioned at the projection node

Ui or

Vi of the current male flower node

fi and selects the subsequent male flower node

fj, two critical routes are involved in this selection process: the main route and the auxiliary route.

In which denotes the main route distance from the projection node Ui of fi to fj, and denotes the auxiliary route distance from the projection node Ui of fi to fj. In the same way, denotes the main route distance from the projection node Vi of fi to fj, and denotes the auxiliary route distance from the projection node Vi of fi to fj. represents the main route distance from male flower fi to male flower fj, and represents the auxiliary route distance from male flower fi to male flower fj.

In which is the main route distance matrix between the projection node Un and the target male flower node, and is the auxiliary route distance matrix between the projection node Un and the target male flower node. As well, the main and auxiliary route matrices between the lower projection point Vn and the target male flower node are, respectively, denoted by symbols and , and their solution processes are similar to Equations (18) and (19).

In accordance with the distance matrix, the heuristic information matrix denotes can be formulated as follows:

denotes the main route heuristic information from the projection node Ui on fi to fj, and denotes the auxiliary route heuristic information from the projection node Ui on fi to fj. and are defined in the same way. denotes the main route heuristic information from male flower fi to male flower fj, and denotes the auxiliary route heuristic information from male flower fi to male flower fj.

3.1.2. Dual-Route Collaborative Probability Model

To address the slow convergence and low route quality in traditional ACO for maize detasseling operation routes, a dual-route collaborative probability decision model is proposed. This model transforms single-route probability calculations into dual-route calculations by combining the probabilities of both routes into the total probability for selecting the next male flower node.

The probability

that the

m-th UDV travels from male flower node

fi to node

fj is calculated as follows:

In which denotes the pheromone concentration on the main route at the t-th iteration. denotes the pheromone concentration on the auxiliary route at the t-th iteration. denotes the candidate set when the m-th UDV is at the male flower node fi. α is the pheromone importance factor; β is the heuristic function importance factor.

includes two terms. The first term denotes the probability of transitioning from male flower node fi to fj through the main route, and the second term denotes the probability through the auxiliary route.

The dual-route collaborative probability decision model, based on the dual-route preference mechanism, removes the longer route between two male flower nodes. This reduces the number of routes for selection and improves the quality of the remaining routes. Additionally, since the endpoints of the main and auxiliary routes include projection nodes Uj and Vj of the male flower node fj, the starting nodes for subsequent selection remain unaffected, preserving the route topology integrity.

3.2. Dynamic Candidate Set

When the model includes many male flower nodes, the ant colony algorithm’s runtime becomes too long. Experiments show that in better solutions, the row difference between consecutively removed male flower nodes is usually 0 to 3. Based on this, a dynamic candidate set mechanism was proposed.

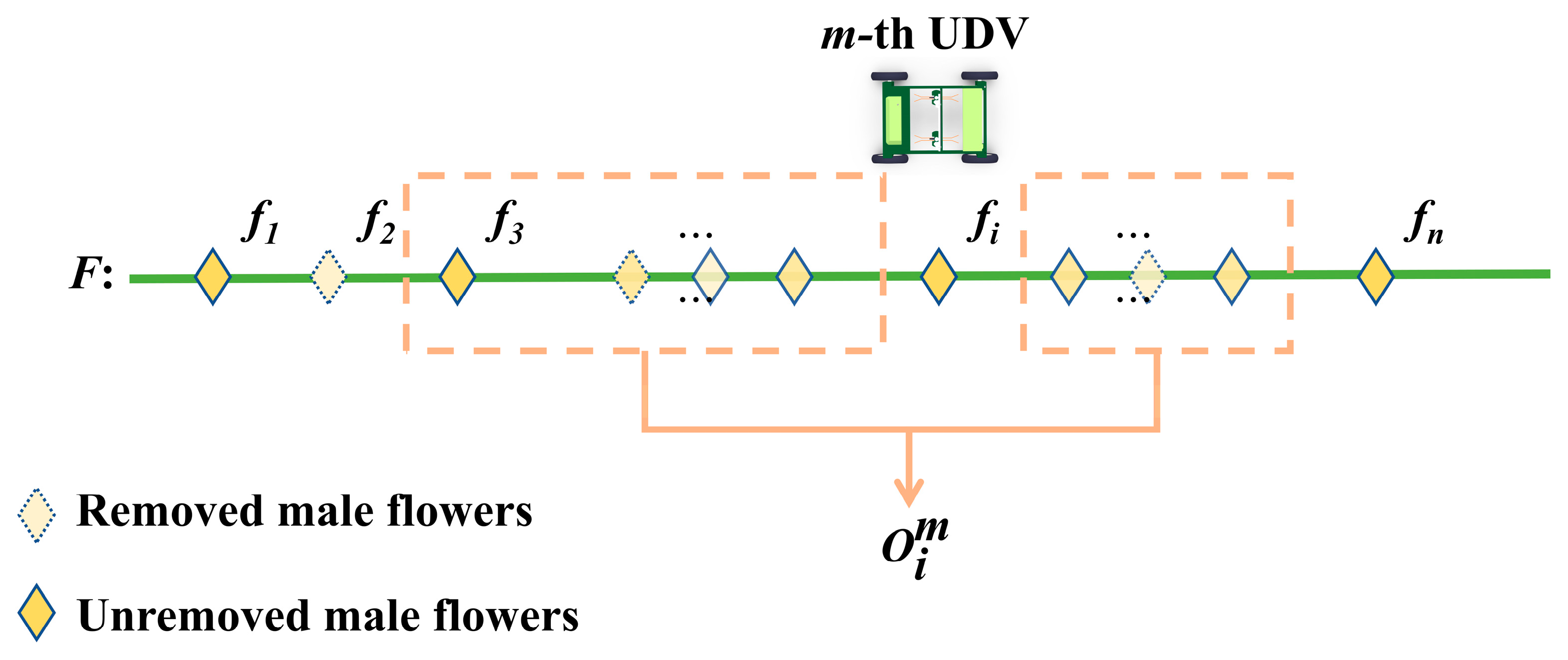

As shown in

Figure 8, the dynamic candidate set is constructed as follows: when the

m-th UDV is at male flower node

fi, a subset of adjacent male flower nodes is selected to form

. To construct

, consider the following:

Firstly, the male flower nodes that have already been removed should be excluded from the candidate set

, as shown by the dashed diamonds in

Figure 8.

Secondly, the candidate set is dynamic, adapting based on the position of fi rather than simply removing eliminated nodes as in traditional ACO.

In addition, it should be noted that the depiction of all male flower nodes in

Figure 8, located on a single crop row, is an abstract representation. In reality, male flower nodes may be distributed across different crop rows. By applying these principles, the size of

is significantly reduced compared to traditional methods, decreasing runtime without compromising optimization quality, as the retained nodes are more likely to produce better routes.

The dynamic candidate set

is defined as follows:

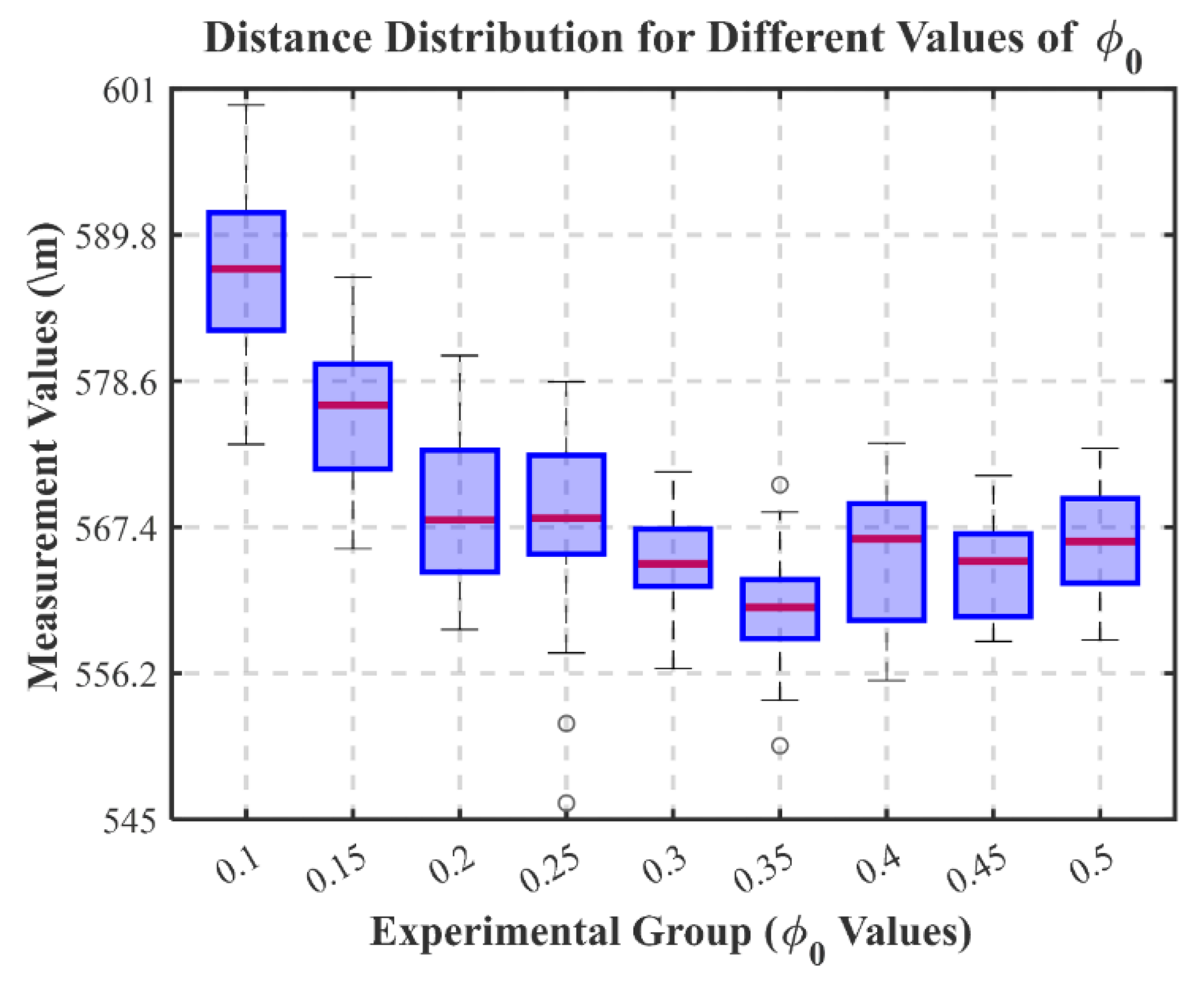

denotes the number of selectable male flowers in the dynamic candidate set. denotes the set of taboo tables, which represents the set of positional coordinates of the traversed male flowers. φ denotes the scale ratio coefficient, with a range of [0, 1], and φ0 denotes the basic scale ratio coefficient.

The dynamic candidate set varies with the position of the male flower node fi and continuously decreases as t increases. This approach ensures global optimization initially, improves convergence later, and reduces runtime.

3.3. Non-Uniform Initial Pheromone Allocation

In the traditional ant colony optimization, the initial pheromone is usually uniformly distributed. This strategy neglects the spatial distribution characteristics of the male flower nodes located in the crop rows in the field, as well as the route constraints and working width conditions of the UDV movement. This leads to many ineffective cross-row searches in the early stage.

For this issue, this study proposes a non-uniform initial pheromone allocation mechanism based on the spatial distribution characteristics of male flower nodes and the intra-row and inter-row coupled constraints. Through inter-row and intra-row collaborative constraints, the algorithm reduces cross-row searches and enhances intra-row routes. An exponential function suppresses cross-row search and assigns multiple pheromone weights to nodes in the same row. This method can prioritize continuous intra-row routes and reduce energy consumption from turnback.

τ0 represents the initial pheromone factor, and its value is 1. γ represents the inter-row attenuation coefficient, while η represents the intra-row enhancement factor. The function δsame(i, j) denotes the same row indicator function. It takes the value of 1 when any projection node of the male flower nodes fi and fj are in the same row of the aisle, and zero otherwise. dij represents the distance from the male flower node fi to fj, including both the main route and the auxiliary route distances; dmax represents the distance of the longest route from male flower node fi to fj.

The first term in Equation (28) is the inter-row attenuation term, which suppresses the generation of redundant cross-row routes. The second term is the intra-row enhancement term, which increases the connection probability of intra-row male flower nodes to achieve continuous operation of UDV. The third term is the distance penalty term, which takes into account the influence of the distance between male flower nodes.

3.4. Direction-Constrained Adaptive Dual-Model Pheromone Regulation

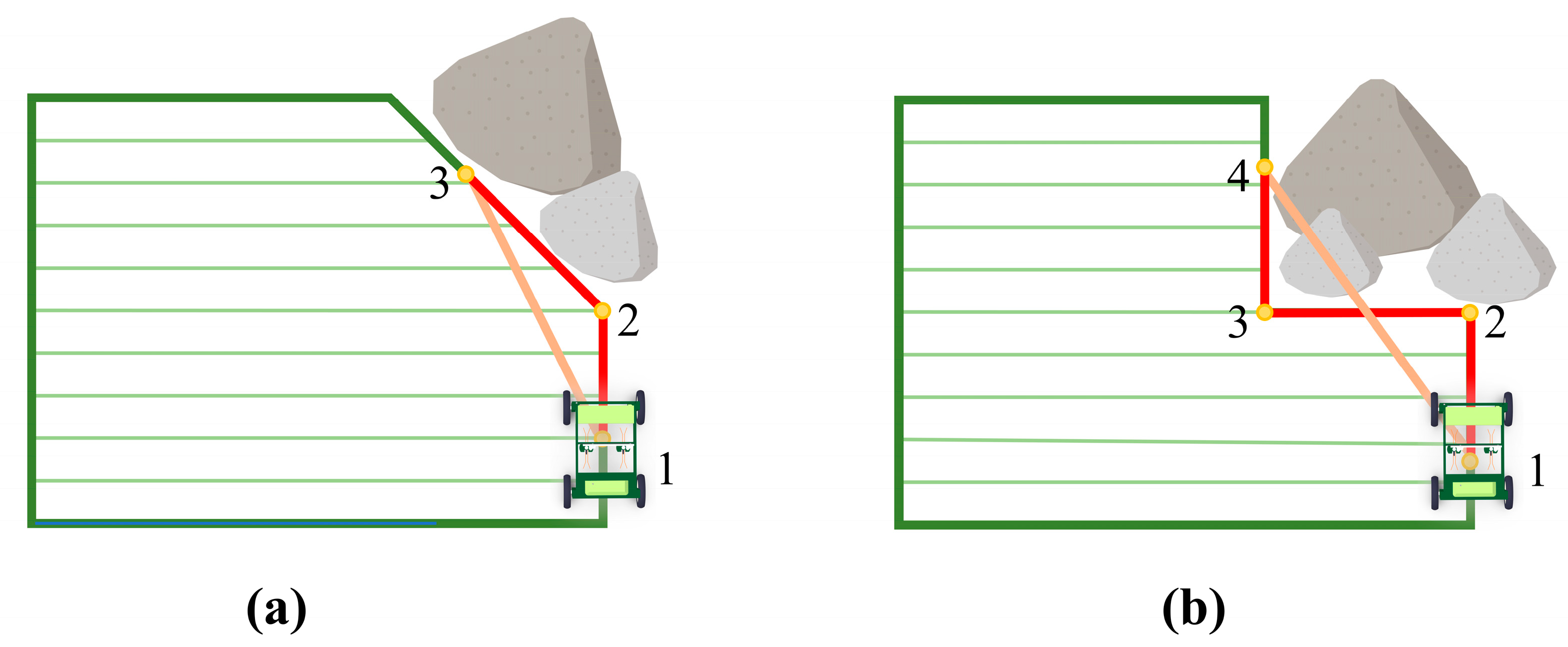

In the traditional TSP model, routes can extend freely without considering intersection or turnback issues, as shown in

Figure 9. However, maize plants are planted in crop rows, which makes the routes between some male flower nodes have one-dimensional characteristics. This demands that UDV operation routes sequentially traverse the projection nodes of male flowers to avoid unnecessary intra-row turnback routes. In contrast, the traditional TSP model distributes nodes in a two-dimensional space, avoiding obvious turnback routes. When male flower nodes are on the same crop row, or their projection points align in the same aisle across different crop rows, obvious turnback routes occur, increasing the total route length.

To address the issue of ineffective turnback routes in traditional ACO for route planning in detasseling operations, this study proposes a direction-constrained adaptive dual-mode pheromone regulation mechanism. This mechanism optimizes intra-row route continuity by combining local penalty and global dynamic evaporation, suppressing intra-row turnback routes.

In the local penalty mode, if the UDV generates a turnback route in the same aisle row, the pheromone deposition amount on this route is penalized to suppress future deposition. The improved pheromone increment

, is calculated as follows:

denotes the pheromone increment on the route of dij from the m-th ant in the iteration t, including the pheromone on the main route and the pheromone on the auxiliary route. ζ denotes the turnback penalty factor, which takes values in the range [0, 1]. dij denotes the intra-row turnback route distance between fi and fj, either the main or auxiliary route. Q denotes the pheromone intensity value.

Under the dynamic global evaporation mode, the pheromone evaporation process is supplemented with an adaptive evaporation coefficient

ρ(t). This coefficient adaptively modulates the evaporation intensity according to the ratio of intra-row turnback routes to the total number of movements. Consequently, this mechanism further enhances the evaporation rate of intra-row turnback routes, thereby facilitating faster convergence toward a more optimal route solution. The improved pheromone update method is as follows:

ρ0 denotes the basic pheromone evaporation coefficient; λ denotes the adjustment coefficient, which controls the sensitivity to the intra-row turnback route. λ = 0 when the route is the forward route, λ ≠ 0 when it is the intra-row turnback route. Nturn denotes the number of intra-row turnback routes; Ntotal denotes the total number of movements.

3.5. Improved ACO Workflow

This section mainly introduces the programming methods and realization approach of DRDM-AACO. To easily facilitate development across different software platforms, we systematically summarize the corresponding pseudocode in

Table 2.

In

Figure 10, the flowchart illustrates the realization process of DRDM-AACO. The green-filled boxes in the figure highlight the differences between DRDM-AACO and the traditional ACO algorithm.

5. Conclusions

This paper explores the route planning challenge for detasseling in maize seed production. It introduces a new algorithm: the Dual-Route and Dual-Mode Adaptive Ant Colony Optimization (DRDM-AACO), which combines multiple mechanisms for hybrid spatial constrained features.

First, a mathematical model was established to optimize detasseling route planning in maize seed production fields. In this model, the set of male flower nodes and the set of crop rows served as inputs, while the detasseling sequence and the approach to each male flower node were defined as outputs. The objective function was formulated to minimize the total length of the detasseling routes. The model proposed a method to establish the projection nodes of male flower spots on different aisles to adapt to the characteristics of the UDV double-row operation width. And based on the projection nodes, a multi-dimensional distance matrix was constructed as the input of DRDM-AACO. Second, the ant colony algorithm was improved through four synergistic mechanisms: (1) Dual-route preference mechanism, (2) Dynamic candidate set mechanism, (3) Non-uniform initial pheromone allocation mechanism, (4) Direction-constrained adaptive dual-mode pheromone regulation mechanism. The proposed algorithm was compared with five algorithms, including ACO and its variants, through example experiments.

The experiment shows that the dual-route preference mechanism increases route diversity and enhances the global optimization ability of the algorithm by improving the heuristic information of the main and auxiliary routes. The non-uniform initial pheromone allocation mechanism guides the UDV to prioritize exploring potential optimal regions by enhancing the pheromone concentration of intra-row routes while weakening that of inter-row routes in the initial environment. The direction-constrained adaptive dual-mode pheromone regulation mechanism addresses the issue of generating turnback routes within a single aisle through the integration of a local pheromone penalty mechanism and an adaptive global evaporation strategy. Through the synergistic operation of four mechanisms, the performance of DRDM-AACO has been significantly enhanced, resulting in optimization results that exhibit a maximum improvement rate of up to 6% compared to ACO. Finally, DRDM-AACO was also applied to conduct example experiments on fields of different sizes and actual farmland. The outcomes were compared against those of three widely adopted algorithms: the Greedy Algorithm, the Boustrophedon Algorithm, and the Improved Boustrophedon Algorithm. Experiments show that DRDM-AACO demonstrates superior performance in various field examples of different sizes and boundary shapes. The optimization results achieved by DRDM-AACO are 11% to 20% shorter than those obtained using the Greedy Algorithm, 11% to 32% shorter than those of the Boustrophedon Algorithm, and 5% to 25% shorter than those of the Improved Boustrophedon Algorithm.

Research demonstrates that the DRDM-AACO proposed in this paper is capable of efficiently generating shorter detasseling operation routes, thereby enhancing the efficiency of detasseling operations in maize seed production fields. Additionally, it contributes to further elevating the automation and intelligence levels of unmanned detasseling vehicles.

Moreover, with minor adjustments, the DRDM-AACO can be effectively adapted for application in agricultural machinery of diverse working widths. Consequently, this study proposes a novel methodology for addressing heterogeneous Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) models, especially route planning challenges in agricultural production.

In the current study, it is essential to explicitly acknowledge several limitations. The proposed DRDM-AACO algorithm mainly focuses on global route planning for male flower nodes at known locations and is validated based on the homogeneous characteristics of maize detasseling fields. It does not investigate real-time dynamic path planning algorithms for UDV operation in the field. The homogeneous environment mentioned in this study limits the impact of issues such as UDV slippage, drift, and increased travel distance caused by factors like soil conditions on the global route planning. Furthermore, this study does not address the situation requiring real-time path planning when obstacles of varying sizes suddenly appear outside the predefined detection range. This paper focuses only on global route planning based on prior knowledge. Real-time obstacle avoidance and course correction are part of real-time path planning, representing another worthy research direction. To further enhance route planning accuracy, addressing the coordination between global route planning and real-time path planning is essential.

The research and application of DRDM-AACO are still in early stages and have limitations that require further exploration. Research can be further explored in the following directions: 1) Cross-field operation route optimization. (1) Cross-field operation route optimization. The multi-field coupling model is constructed to systematically address connection route generation and operation sequence optimization. (2) Multi-machine collaborative scheduling strategy. Using the vehicle routing problem (VRP) framework, route optimization for multiple UDVs operating in large field areas is developed. (3) Develop a hierarchical decision-making framework that combines the global optimization path with the real-time perceived dynamic environmental information. This framework will enable the UDV to efficiently adjust its path upon encountering new information such as obstacles and slippage, thereby ensuring the integrity and efficiency of the operation.