Abstract

In traditional scallion cultivation, the bare-root transplanting method—which involves direct seeding, seedling raising in the field, and lifting—is commonly adopted to minimize seedling production costs. However, during the mechanized transplanting of bare-root scallion seedlings, practical problems such as severe seedling damage and poor planting uprightness exist. In this paper, the Hertz–Mindlin with Bonding contact model was used to establish the scallion seedling model. Combined with the Plackett–Burman experiment, steepest ascent experiment, and Box–Behnken experiment, the bonding parameters of scallion seedlings were calibrated. Furthermore, the accuracy of the scallion seedling model parameters was verified through the stress–strain characteristics observed during the actual loading and compression process of the scallion seedlings. The results indicate that the scallion seedling normal/tangential contact stiffness, scallion seedling normal/tangential ultimate stress, and scallion Poisson’s ratio significantly influence the mechanical properties of scallion seedlings. Through optimization experiments, the optimal combination of the above parameters was determined to be 4.84 × 109 N/m, 5.64 × 107 Pa, and 0.38. In this paper, the flexible planting components of scallion seedlings were taken as the research object. Flexible protrusions were added to the planting disc to reduce the damage rate of scallion seedlings, and an EDEM-ADAMS coupling interaction model between the planting components and scallion seedlings was established. Based on this model, optimization and verification were carried out on the key components of the planting components. Orthogonal experiments were conducted with the contact area between scallion seedlings and the disc, rotational speed of the flexible disc, furrow depth, and clamping force on scallion seedlings as experimental factors, and with the uprightness and damage status of scallion seedlings as evaluation criteria. The experimental results showed that when the contact area between scallion seedlings and the disc was 255 mm2, the angular velocity was 0.278 rad/s, and the furrow depth was 102.15 mm, the performance of the scallion planting mechanism was optimal. At this point, the uprightness of the scallion seedlings was 94.80% and the damage rate was 3%. Field experiments were carried out based on the above parameters. The results indicated that the average uprightness of transplanted scallion seedlings was 93.86% and the damage rate was 2.76%, with an error of less than 2% compared with the simulation prediction values. Therefore, the parameter model constructed in this paper is reliable and effective, and the designed and improved transplanting mechanism can realize the upright and low-damage planting of scallion seedlings, providing a reference for the low-damage and high-uprightness transplanting operation of scallions.

1. Introduction

Scallions are one of the important economic crops in China [1], with an average annual planting area reaching 500,000 hectares, accounting for 70% of the global export share [2]. Currently, the main domestic scallion varieties include Zhangqiu Dawutong, Shouguang Bayeqi, and Tianjin Gaojiaobai. The planting areas are mainly distributed in Shandong, Henan, etc., regions. As a special variety, Zhangqiu scallion is mainly cultivated in Shandong and has been exported overseas.

At present, Zhangqiu scallion cultivation has been scaled up. Unlike other vegetables, which are transplanted as pot seedlings, Zhangqiu scallions are usually manually transplanted through the process of “field sowing for seedling raising—seedling lifting—bare seedling transplanting”. Among the total cultivation area, the area under efficient mechanized transplanting accounts for less than 10%, and the industry still relies heavily on manual transplanting [3]. Specifically, manual transplanting only achieves a daily area of 333–400 m2 per worker, which is associated with high labor intensity, low seedling uprightness, and a lack of corresponding professional machinery [4,5].

Developed countries began developing vegetable transplanters as early as the 1950s and 1960s and have successively developed semi-automatic and fully automatic transplanters suitable for transplanting small-seedling vegetables [6]. In the field of potted scallion seedling transplanting, the disc-clamp transplanters developed by Germany [7] and the jaw-clamp transplanters produced by Checchi & Magli (Budrio, Italy) [8] can complete field transplanting of vegetables and achieve relatively high seedling uprightness. However, the sizes of the disc clamps and jaw clamps cannot fit Chinese scallion seedlings during transplanting, resulting in poor transplanting effect and quality as well as a relatively high damage rate. The KN-P6 semi-automatic transplanter developed by Kubota (Osaka, Japan) [9] has a simple and compact structure but requires manual seedling feeding, leading to low production efficiency. The 2ZS-2 (VP245B) fully automatic potted seedling transplanter produced by Yamaco Company (Osaka, Japan) [10] can realize fully automatic transplanting of potted scallion seedlings through a specially designed seedling tray. Nevertheless, most of these vegetable transplanters are mainly suitable for transplanting small seedlings and potted seedlings and have a low degree of integration with Zhangqiu scallion cultivation agronomy.

Although China has developed various transplanters for bare-seedling crops such as scallions to promote mechanization, most of them fail to fully meet the agronomic requirements for uprightness and damage rate during the transplanting of Zhangqiu scallions. For example, the 2ZYX-2 scallion transplanter produced by Shandong Hualong Agricultural Equipment Co., Ltd. (Weifang, China) [11] can achieve semi-automatic transplanting with manual auxiliary seedling placement to improve the efficiency of scallion transplanting operations. However, due to the limitations of manual seedling placement, scallion seedlings enter the planting mechanism in inconsistent postures, making it impossible to ensure transplanting uprightness. The flexible-disc scallion transplanter developed by Hu Jun et al. [12] has realized semi-automatic transplanting of scallions, but it can only complete single-row operations at a time, and the problem of unstable scallion uprightness needs to be further solved. To address the issue of low uprightness during scallion transplanting, Li Zhen from Shandong Agricultural University [13] designed a chain-clamp scallion transplanter, which completes scallion planting through the cooperation of seedling clamps and seedling grooves installed on the conveyor chains of the seedling-dropping and seedling-feeding mechanisms, respectively. This transplanter achieves relatively high uprightness, but the problem of seedling damage still exists.

Summarizing the above research findings, most automatic transplanters at home and abroad are only suitable for pot seedling transplanting, and there is no transplanting machinery designed specifically for bare seedling transplanting, especially for Zhangqiu scallion. Although some semi-automatic transplanting machines are suitable for bare seedling transplanting, due to the fact that bare seedling transplanting has no substrate and the roots have no self-weight, problems such as poor uprightness and high damage rate exist in the transplanting process compared with pot seedling transplanting.

To address the issues of low uprightness and high vulnerability to damage in domestic scallion mechanical transplanting, an automatic transplanter suitable for bare seedling transplanting was designed in accordance with the transplanting agronomic requirements of Zhangqiu scallions. Based on the deformation characteristics of scallion seedlings during transplanting, the parameters of the scallion seedling model were calibrated. These calibrated parameters were then used to conduct numerical simulations of real-world scenarios involving scallion seedlings and flexible disc planting components during the planting process, so as to simulate the working process of the planting components. A three-factor, three-level orthogonal experiment was designed to explore the optimal combination of design parameters, and field experiments were conducted for verification. This research provides a reliable basis for the optimization and design of planting mechanisms in scallion seedling transplanting operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Structure of Scallion Transplanting Machine

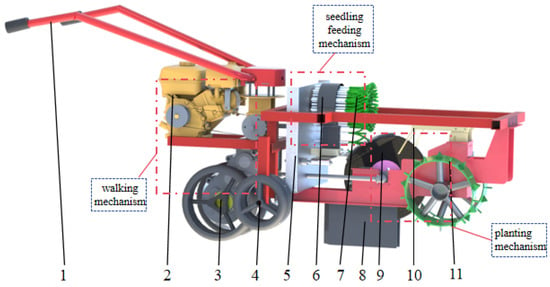

The scallion transplanting machine is shown in Figure 1. It mainly consists of three parts: a walking mechanism, a seedling feeding mechanism, and a planting mechanism, including handrails, an engine, walking wheels, depth limiting wheels, planting plates, seedling belts, trenchers, planting discs, and limiting devices. The parameters of the whole machine are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the scallion transplanting device. (1) Handrail, (2) engine, (3) Walking Wheel, (4) Depth Limiting Wheel, (5) Planting Plate, (6) Seedling Belt, (7) Scallion Seedlings, (8) Furrower, (9) Planting Disc, (10) Positioning Device, and (11) Soil-Covering Wheel.

Table 1.

Technical Specifications of Machinery.

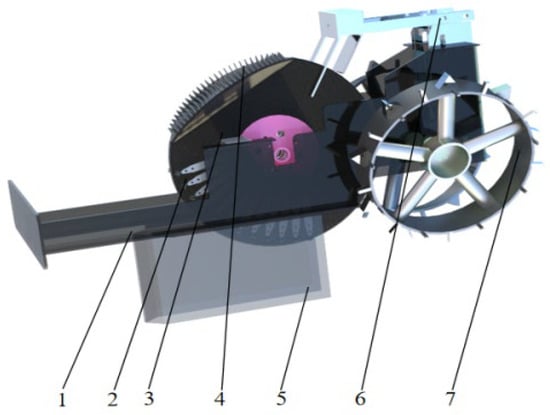

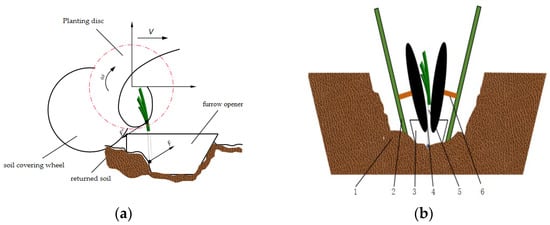

The onion seedling planting mechanism is located at the rear of the transplanting machine, and the soil-covering wheel transmits power to the planting mechanism through gear meshing. The main structure of the planting component is shown in Figure 2, which mainly consists of a fixed bracket, elastic roller, planting disc, flexible protrusion, furrow opener, limit fork, and soil-covering wheel.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the planting components. (1) Fixed Support Bracket, (2) Elastic Roller, (3) Planting Disc, (4) Flexible Protrusions, (5) Furrower, (6) Limiting Fork, and (7) Soil-Covering Wheel.

2.2. Overall Structure of Planting Institution

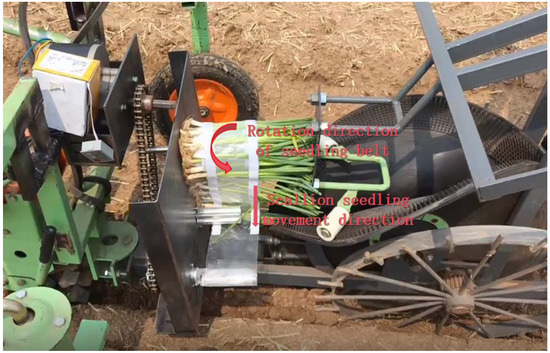

During the planting process, the scallion seedlings are secured within the seedling belt and move downward with it as shown in Figure 3. The rubber disc opens under the action of the limit fork, then closes the front under the action of the clamping device, clamps the scallion seedlings in the seedling belt and rotates. When the disc rotates to the scallion seedling separation point, the flexible disc loses the pressure applied by the elastic roller, thereby releasing the scallion seedlings. Under the combined action of soil resistance and the friction force on the scallion seedlings when they leave the disc, upright planting is achieved.

Figure 3.

Shape of the scallion seedling during the transplanting process.

3. Planting Mechanism Design

3.1. Motion Trajectory and Working Stroke Analysis

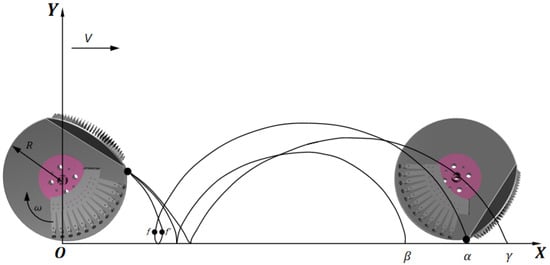

The motion trajectory of the flexible disc is a combination of the transplanting machine’s forward movement and the disc’s own rotation [14]. It is primarily influenced by the machine’s forward speed (V1) and the disc’s rotational speed (V2). The motion trajectories of the clamping point under different speed combinations are shown in Figure 4. When analyzing the motion trajectory during the scallion seedling clamping process, the forward direction of the transplanting machine is defined as the positive X-axis direction, the vertical direction as the positive Y-axis direction, and the coordinate origin as O (0, 0). Among these parameters, Vx represents the velocity component of the scallion seedling clamping point along the X-axis, and Vy represents that along the Y-axis. For convenience of calculation, the forward speed of the transplanting machine is set as V1 and the linear speed of the planting disc as V2.

where ω is the angular velocity of the planting tray and t is the forward movement time of the planting device.

Figure 4.

Motion trajectory of the scallion seedling gripping point.

In the actual planting process, as the scallion seedlings are carried by the disc to the release position, the roots of the scallion seedlings are first buried in the soil, while the upper parts of the scallion leaves remain in the planting disc and are subjected to the thrust F′ in the direction of rotation of the disc, and the roots of the scallion seedlings are subjected to the relative forward thrust F of the returning soil, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the interaction between the scallion seedling–machine–soil during the planting process. (a) v represents the forward speed, ω represents the rotational speed of the disc, F represents the force exerted by the backflow soil on the scallion seedlings, and F′ represents the force exerted by the planting disc on the scallion seedlings. (b) (1) Return soil, (2) Soil-covering wheel, (3) Trench opener, (4) Planting disc, (5) Scallion seedlings, and (6) Transmission gear.

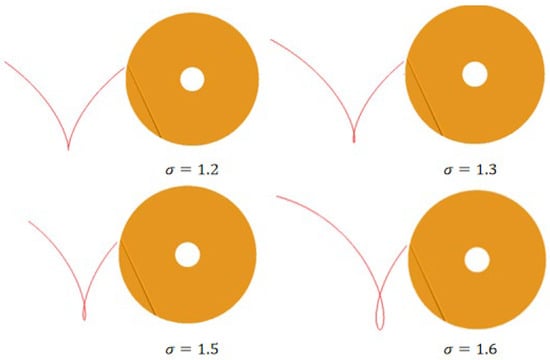

Since the movement trajectory of the scallion seedlings is related to the forward speed of the machine and the rotational speed of the disc, the ratio σ affects the movement trajectory of the scallion seedling clamping point; that is

Different values of σ lead to different trajectories of the planting disc’s clamping point. When the transplanting machine’s forward speed is lower than the planting disc’s linear speed (i.e., σ < 1), the clamping point’s trajectory is as shown in curve γ in Figure 4. Correspondingly, the scallion seedling’s trajectory follows a cycloid. If the scallion seedling is released under this condition, it will be subjected to a high horizontal velocity in the transplanting machine’s forward direction, causing the planted seedling to tilt forward.

When the forward speed of the machine is equal to the linear speed of the planting tray, i.e., σ = 1, the motion trajectory is shown by β, which is consistent with the “zero speed seedling planting” theory [15,16]. However, in actual operation, when the scallion seedlings are released, some of the green parts of the scallions will still be affected by the force of the tray, and at this time, the scallion seedlings will still have a large inclination angle.

When the forward speed of the machine is equal to the linear speed of the planting tray, i.e., σ > 1, the motion trajectory is shown as α. At this point, a turning point will appear on the curve. When the scallion seedlings are released, they will be pushed forward by the soil and backward by the tray, thereby keeping the scallion seedlings upright [17].

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that only the clamping point with rotation has the minimum X-axis component velocity. Combining the analysis of (1), it can be seen that when t = 2πn, the clamping point has the minimum X-axis component velocity. The condition for the planting device to operate normally is V1 < V2, where the relationship between V2 and ω is as follows, where R is the radius of the flexible planting disc.

If the disc R is too small, the closing area and clamping force of the disc will be too small, and effective seedling clamping cannot be achieved. If R is too large, rotational energy consumption will rise, along with an increase in the overall size and weight of the transplanting equipment. Considering that the length of scallion seedlings is 182.6–210.8 mm, in order to avoid the seedlings touching and tangling with each other in the disc and to ensure the effectiveness of seedling reception and planting, R is set to 300 mm.

According to the literature, the value range of σ should be between 1.0 and 2.0 [18]. If σ is too large, the scallion seedlings will easily accumulate at the clamping point of the disc; if σ is too small, it will have a significant impact on the efficiency of the transplanting work. Based on the above analysis and the value range of σ, four sets of ratios, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 1.6, were selected, and ADAMS software (ADAMS 2019 MSC Software, Los Angeles, USA) was used to analyze the motion trajectory of the scallion seedling clamping point, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Motion trajectory of scallion seedlings at different gripping points with varying values.

By analyzing the trajectory diagram of scallion seedlings, it can be concluded that the larger the σ value, the more obvious the rotation phenomenon of the scallion seedling trajectory, and the more prone the scallion seedlings are to falling over during transplantation [19]. Considering the actual operation process, in order to ensure reasonable planting spacing and uprightness of the scallion seedlings, the σ value is determined to be 1.5.

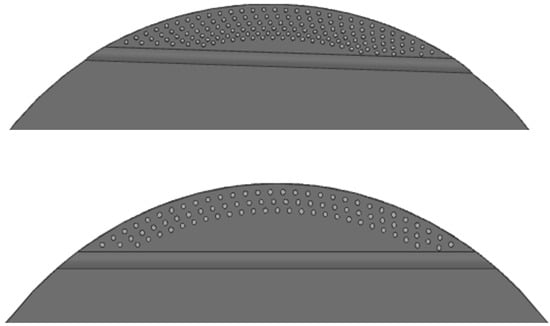

To protect the scallion seedlings during the clamping stage, ensure even force distribution, and prevent them from piling up inside the planting disc, a ring of flexible protrusions is thus designed around the disc edge, as shown in Figure 7. To facilitate subsequent coupling simulation tests, the 20 mm long flexible protrusions are simplified to cylindrical protrusions, and two arrangement types are adopted, with distribution widths of 40 mm and 20 mm, respectively. The contact area between each cylindrical protrusion and a scallion seedling is 7 mm2.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the flexible protrusions at the edge of the disc.

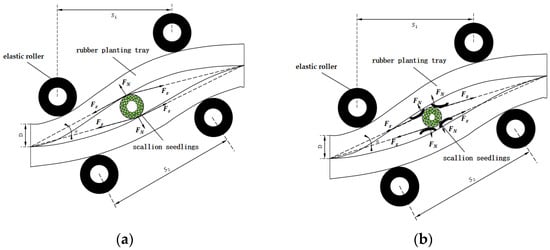

The stress analysis of the interaction between the flexible disc and scallion seedlings is shown in Figure 8. It can be observed that the edge of the disc’s closed area is compressed by the external elastic roller, resulting in wavy deformation that increases the clamping force on scallion seedlings. Considering that scallion seedlings have a diameter of approximately 10 mm, an elastic roller with a diameter of 20 mm is selected to enhance transplant stability. The stress calculation formula for scallion seedlings is as follows:

Figure 8.

Force analysis diagram between the flexible disc and scallion seedlings. (a) Force analysis of holding scallion seedlings with a rigid disc clamp. (b) Force analysis of scallion seedlings held by a flexible protruding disc clamp.

3.2. Measurement of Physical Characteristics of Scallion Seedlings

The test material was selected from high-quality Zhangqiu scallion seedlings. Thirty-five scallion seedlings with similar growth rates were divided into five groups, with seven seedlings in each group. A ruler was used to measure each group of scallion seedlings, and a vernier caliper was used to measure their diameter. Multiple measurements were taken, and the average value was taken as the result. The length of the scallion seedlings was measured to be between 210.3 and 280.5 mm, and their diameter was between 8.3 and 11.4 mm, the specific parameters are shown in Table 2. The roots and leaves of the scallion seedlings were long and intertwined, which could easily affect the uprightness of the seedlings during mechanical transplanting. To ensure the quality of transplanting, the scallion seedlings needed to be pruned. In the experiment, in order to ensure consistency with the actual transplanting situation, the roots and leaves of the experimental scallion seedlings were also pruned. Research shows that root pruning has little effect on scallion growth [20], while leaf pruning to half the original length yields the best growth; after treatment, the length from the white base to the green tip ranges from 182.6 to 210.8 mm.

Table 2.

Macroscopic characteristic parameters of scallion seedlings.

3.3. Density Measurement

The mass of each scallion seedling was accurately measured with an electronic balance. Each seedling was then placed individually in a water-filled measuring cup, and the volume of displaced water was recorded. The volume of each seedling was calculated based on the displaced water volume, and the density of the tested seedlings—derived from the mass-to-volume ratio—was determined to be 870.5 ± 22.01 kg/m3.

3.4. Measurement of Contact Parameters

The physical parameters to be measured in this paper include: the collision recovery coefficient between scallion seedlings, the collision recovery coefficient between scallion seedlings and planting rubber discs, the static friction coefficient, and the rolling friction coefficient.

The planting rubber discs used for planting are 3 mm thick silicone rubber pads with a Poisson’s ratio of 0.47, a density of 870 kg/m3, and a shear modulus of 2.9 GPa.

3.4.1. Determination of Collision Recovery Coefficient

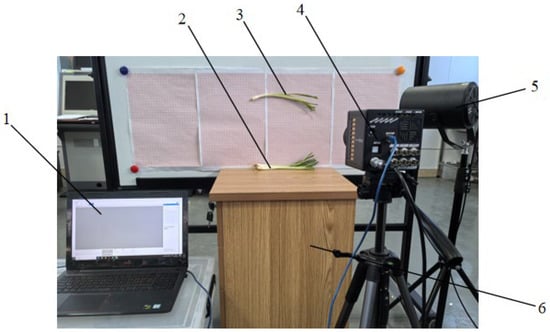

The collision recovery coefficient is a parameter that reflects the ability of an object to return to its original state after a collision. It is defined as the ratio of the approach velocity of the two objects along the normal direction of the contact point before the collision to the separation velocity of the two objects after the collision [21]. The collision recovery coefficient test bench is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Measurement of restitution coefficient in collision. (1) Computer, (2) Scallion seedling row, (3) Test scallion seedlings, (4) High-speed camera, (5) Supplementary lighting system, and (6) Test rig.

A high-speed camera was placed directly in front of the test bench, ensuring that the distance between the high-speed camera and the test bench was 800 mm. To ensure that the scallion seedlings would collide with the test area when they fell, it was necessary to ensure that the test area had a sufficient contact area. Therefore, test scallion seedlings with a length of 190 mm and a diameter of 10 mm were selected for the experiment. A single scallion seedling was dropped freely from a height of 250 mm above the scallion seedling group. After the scallion seedling collided, it bounced to a certain height, and the entire process was recorded using a high-speed camera [22]. When measuring the coefficient of restitution between scallion seedlings and silicone rubber, the scallion seedling group was replaced with silicone rubber, and all other procedures remained the same as above.

Assuming that scallion seedlings are only affected by gravity during free fall, and disregarding other factors that may affect their descent, the following can be obtained from the law of conservation of energy.

Normal velocity of scallion seedlings before collision:

Normal velocity after collision separation:

The collision recovery coefficient obtained is

where is normal velocity before collision, m/s; is normal velocity after collision, (m/s); is falling height before collision, (mm); and is maximum bounce height, (mm).

After repeated experiments, the collision recovery coefficient between scallion seedlings was found to be 0.1 to 0.2, and the collision recovery coefficient between scallion seedlings and silicone rubber discs was found to be 0.3 to 0.4.

3.4.2. Friction Coefficient Measurement

In the static friction coefficient measurement test, one end of the 65 Mn steel plate was fixed, and a silicone rubber pad was placed on the plate’s surface. The other end was slowly lifted until the scallion seedlings on the pad began to slide, at which point the test was stopped and the angle between the steel plate and the tabletop was recorded [23]. In the dynamic friction coefficient measurement test, the silicone rubber pad was placed flat on the table, the scallion seedling was connected to a spring force gauge, the other end of the spring force gauge was connected to a sliding table, and uniform motion was performed to record the spring force reading. The static and kinetic friction coefficients were calculated using Equations (8) and (9), respectively.

where μ1 is the static friction coefficient; φ1 is the angle between the soft pad and the horizontal plane when the scallion seedling is about to slide; μ2 is the dynamic friction coefficient; Ff is the friction force between the scallion seedling and the silicone soft pad when the scallion seedling moves at a constant speed, N; m is the mass of the scallion seedling, kg; and g is the gravitational acceleration, m/s2.

The final test results show that the static friction coefficient between scallion seedlings and silicone rubber ranges from 0.2 to 0.3, while the rolling friction coefficient between them ranges from 0.4 to 0.5.

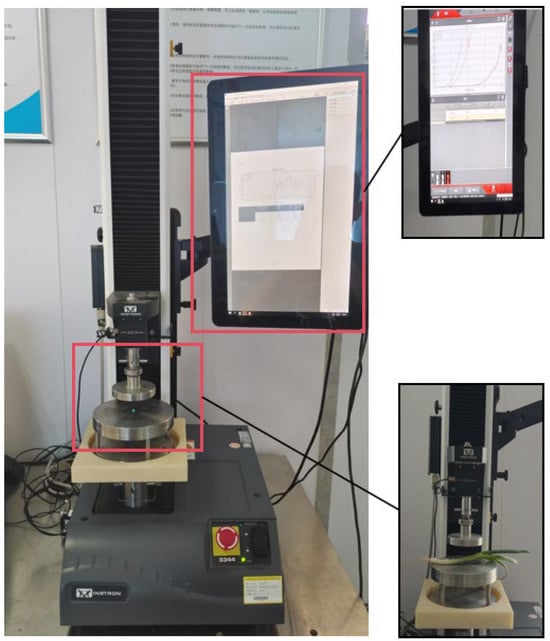

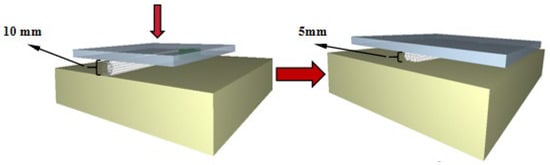

3.5. Scallion Seedling Compression Test

The INSTRON-3344 (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) universal testing machine was used in conjunction with a load sensor to conduct radial compression tests on scallion seedlings. The equipment is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Mechanical property testing apparatus.

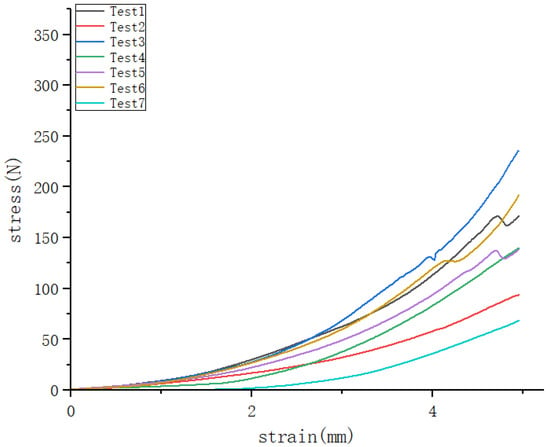

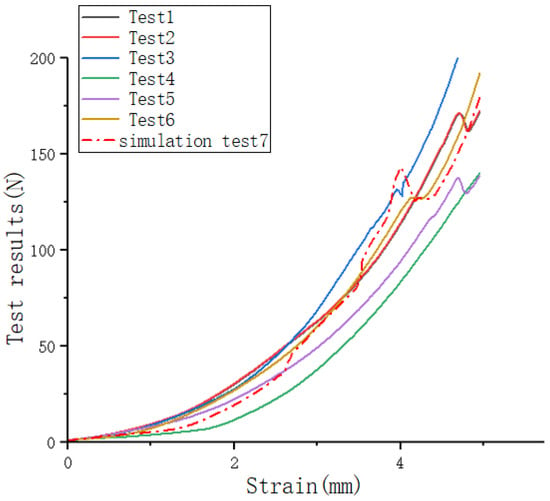

From the prepared scallion seedling samples, seven scallion seedlings were randomly selected as radial compression test specimens. During the test, the upper press applied a load to each specimen at a loading rate of 100 mm/min. Each scallion seedling specimen was placed vertically in the middle of the lower platform, perpendicular to its growth direction. The first peak on the force–strain curve was defined as the maximum radial compressive force of the scallion seedling, and the corresponding strain was recorded [24]. The test was repeated seven times, and the data was used to derive the stress–strain curve of the scallion seedlings. The second set of tests with large errors was removed, and six sets of valid data were retained. The maximum radial compressive forces of the scallion seedlings obtained from the six tests were 181.2 N, 191.6 N, 162.9 N, 137.5 N, 127.2 N, and 171.1 N, respectively, and the stress–strain curves are shown in Figure 11. Due to the different maximum radial compressive forces of different scallion seedlings, the average value of 140.6 N was taken as the result.

Figure 11.

Stress–strain curve of scallion seedlings in physical testing.

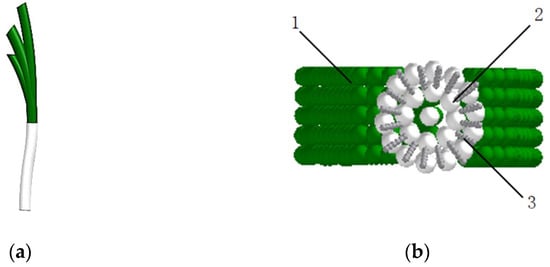

3.6. Model Correction Method

To ensure that the scallion seedling model used for simulation is closer to reality, when modeling the scallion seedling, the white part and the green part of the scallion seedling are given a certain curvature, and the white part of the scallion seedling is modeled using a hollow double-layer bonding model and the spatial coordinate method [25,26]. The clamped section of the white part is represented as a cylinder in the simulation. In the spatial coordinate system, the XOY plane is used as the cross-section of the scallion seedling, the Z-axis direction is the growth direction of the scallion seedling, and point O (0, 0, 0) is the coordinate of the center of the cross-section. The particles on the cross-section are distributed in a circle, and the established plane figure is copied and stacked until the required length is reached, as shown in Figure 12. The density and shear modulus of the scallion seedling model are 870 kg/m3 and 2.62 MPa [27], respectively. The particle filling radius is 1.5 mm, and the bonding radius is 2 mm. The smaller the particle radius, the closer the simulation is to the actual mechanical characteristics, but the simulation calculation time will increase. Larger particle radii result in faster strain propagation between particles, reducing simulation accuracy. To balance simulation accuracy and efficiency, a particle radius of 1.5 mm is selected. This choice yields relatively accurate results—particularly in terms of particle displacement ratios—while reducing simulation computation time.

Figure 12.

Stress–strain curve of scallion seedlings in physical testing. (a) Three-dimensional model of scallion seedling. (b) Scallion seedling discrete element modeling front view. (1) Scallion leaf granules. (2) Scallion white granules. (3) Root granules.

In the mechanical simulation test of scallion seedlings, the modeled length of the seedlings matched the length used in the actual physical test. To simplify the simulation calculation, only the main test components were retained, and the BOX function in EDEM software was used to create the mold. The time step in the simulation test was set to 2 × 10−6 s. Based on the actual physical test of radial compression of scallion seedlings, the compression fixture above the scallion seedlings applied a load to the model at a loading speed of 0.2 m/min [28]. The radial compression simulation model of scallion seedlings is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Radial compression simulation experiment of scallion seedling.

3.7. Selection of Bonding Parameter Range

Since the modeling of scallion seedlings is isotropic inside and outside, the contact stiffness between the particles inside and outside the scallion seedlings is set to be consistent with the ultimate stress. In order to investigate the influence of various bonding parameters on the modeling of scallion seedlings, multiple experiments were conducted [29] to reasonably increase the range of experimental parameters, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bonding Parameters of Scallion Seedling Clamping Model.

3.7.1. Plackett–Burman Screening Test

The eight factors screened from Table 3 were used to design a Plackett–Burman experiment using Design-Expert 13 software, with the maximum and minimum codes set to +1 and −1, respectively, as shown in Table 4. Table 5 presents the design and results of the Plackett–Burman experiment, where X1 to X8 represent the coded values of the factors listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Factor Encoding Values of Plackett–Burman.

Table 5.

Design and results of Plackett–Burman test.

According to the significance analysis results in Table 6, factors X1, X2, and X3 have a significant effect on the compressive force exerted on scallion seedlings. Therefore, subsequent experiments mainly focused on the calibration and optimization of the three factors X1, X2, and X3. The remaining factors that have a relatively small effect on the radial compressive force on scallion seedlings were set at intermediate levels. Specifically, X4 was set to 0.35, X5 to 0.15, X6 to 0.5, X7 to 0.45, and X8 to 0.25.

Table 6.

Factors, Levels, and Significance Analysis of Plackett–Burman Experiment.

3.7.2. Steepest Climb Test

Table 7 shows the design and results of the steepest climb test. The results indicate that Test 4 had the smallest relative error of 1.28%.

Table 7.

Steepest Ascent Experiment.

3.7.3. Box–Behnken Experiment and Analysis

Take the experiment with the smallest relative error among the above experiments, Experiment 4, as the intermediate level (0), and use Experiments 3 and 5 as the low level (−1) and high level (+1), respectively. The coding is shown in Table 8. A Box–Behnken experiment was conducted, and the results are shown in Table 9.

Table 8.

Significant Contact Parameter Level Encoding.

Table 9.

Design and Results of Box–Behnken Experiment for Significant Contact Parameters.

Regression analysis of the test results in Table 9 yielded the following regression model equation for the maximum radial compression force of scallion seedlings and the significance parameter:

The p value of the fitted model is <0.01, the coefficient of determination R2 = 0.9995, and the adjusted coefficient of determination R2adj = 0.9988, both of which are close to 1, and the signal-to-noise ratio is 119.0, indicating that the model is highly significant and can predict the compressive force exerted on scallion seedlings during the actual planting process. The results of the variance analysis of the model are shown in Table 10. It can be seen that the scallion seedling method/tangential contact stiffness (X3), scallion seedling method/tangential limit stress (X4), and scallion seedling Poisson’s ratio (X5) have a significant effect on the radial compressive force of scallion seedlings.

Table 10.

Analysis of Variance for Regression Model in Box–Behnken Experimental Design.

3.7.4. Verification of the Optimal Parameter Combination Through Simulation

Using the optimization module in Design-Expert 13 software (Design-Expert 13 Stat-Ease Minneapolis, MN, USA), based on the actual maximum radial compression force of 140.6 N for scallion seedlings, a constrained objective optimization solution was obtained for the regression model, resulting in three sets of parameters with a relative error of less than 8% compared to the physical test data. The radial compressive force corresponding to the optimal parameter set was compared with the actual measured maximum radial compressive force of scallion seedlings, and the comparison results are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Comparison of Experimental and Simulation Results for Mechanical Tests.

As can be seen from the data in Table 11, when the scallion seedling method/tangential contact stiffness is 4.842 × 109 N/m, the scallion seedling method/tangential limit stress is 5.643 × 107 Pa, and the scallion seedling Poisson’s ratio is 0.38, the test results and the measured results show the smallest error, indicating that the simulation model is highly reliable. This shows that the established scallion seedling model can be used to represent the stress conditions of actual scallion seedlings during the mechanical transplanting process. To further verify the model’s accuracy, the stress–strain curve from the simulation test (with the smallest error in this parameter set) was compared with the stress–strain curve from the physical test, as presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Comparison of stress–strain curves between experimental mechanical testing and simulation testing.

As shown in the figure, the maximum radial compressive force in the physical compression test of scallion seedlings occurred at a strain of 4.3 mm, while that in the simulation test of the constructed scallion seedling model occurred at a strain of 4 mm. When the simulated test strain was the same as the measured strain, the stress values of the model and the actual test sample were basically the same, with an error of less than 5%.

4. Planting Performance Analysis and Parameter Optimization Based on the Discrete Element Method

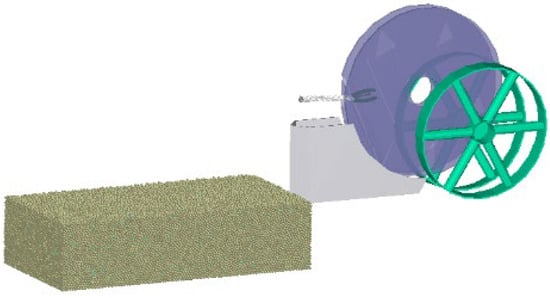

4.1. Coupled Simulation

To ensure consistency between simulation and testing, the length of the scallion seedlings used in the simulation was set at 190 mm and the diameter at 10 mm. Given that air has minimal influence on the scallion seedling transplanting process, the simulation environment was set to a gravity-enabled vacuum, with gas flow excluded [30]. The scallion seedlings were generated at designated positions on the planting disc. The simplified three-dimensional model of the planting component previously modeled by NX12.0 software was imported into EDEM software (EDEM 2022 Altair Engineering, Michigan, USA), and the motion parameters of the planting component were set in ADAMS software (ADAMS 2019 MSC Software, Los Angeles, USA) to start the simulation test, as shown in Figure 15. The simulation area was 800 mm × 400 mm, The simulation parameters are shown in Table 12.

Figure 15.

Simulation Experiment.

Table 12.

Simulation Parameter Design.

4.2. Simulation Test Design

After theoretical analysis and testing, the contact area X1 of the scallion seedling clamping point, the disc rotation speed X2, and the digging depth X3 were selected as test factors. According to the previous ADAMS kinematic test, excessive forward speed will exacerbate the lodging of scallion seedlings, and if the disc rotation speed X2 is too low, it will cause the planting spacing of scallion seedlings to be too small. Therefore, based on practical conditions and the above analysis, coupled simulation experiments were conducted under a significance level of σ = 1.5, the simulation factors and their levels are shown in Table 13. The factor levels were set as follows:

Table 13.

Simulation Factors and Levels.

- X1 (contact area of clamping point): 105 mm2, 255 mm2, and 405 mm2 (note: 105 mm2 and 255 mm2 contact areas have flexible protrusions distributed around the disc, while 405 mm2 has none);

- X2 (disc rotation speed): 0.15–0.35 rad/s;

- X3 (planting depth): 40 mm, 100 mm, and 160 mm.

The Box-Behnken results are shown in Table 14.

Table 14.

Box–Behnken Experimental Design Regression Model and Results.

To verify the planting effect, the post-planting uprightness and damage rate of scallion seedlings are generally adopted as evaluation indicators. Since the damage rate is difficult to express intuitively in the simulation process, the radial compressive force exerted on the scallion seedlings during the simulation process is used to express it indirectly. Based on the maximum compressive force F exerted on the scallion seedlings in the actual physical test and the radial compressive force Y2 exerted on the scallion seedlings in the simulation test, it is determined whether the scallion seedlings are damaged; that is, if the clamping force during the transplanting process exceeds the maximum radial compressive force, it is determined that the scallion seedlings are damaged. The calculation formula for the damage rate p is as follows:

where is total number of seedlings taken; is total number of damaged scallion seedlings.

4.3. Simulation Results Analysis and Optimization

A three-factor, three-level orthogonal test design was adopted, where Factors A, B, and C corresponded to the previously identified test factors (contact area of clamping point, disc rotation speed, and planting depth). The evaluation indicators included the post-planting uprightness of scallion seedlings and the radial compressive force applied during the clamping process. A total of 17 sets of combined tests were conducted, in which the damage rate of scallion seedlings was determined based on the different forces applied to the scallion seedlings in each test group. The test factors and results are shown in Table 15.

Table 15.

Analysis of Variance Results.

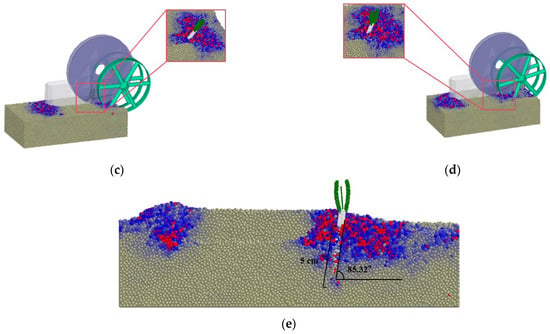

In order to clarify the interaction between the planting mechanism and the scallion seedlings during the planting process and explore the planting mechanism, an analysis was conducted using A 255 mm2, B 0.25 rad/s, and C 100 mm as examples. The coupled simulation process is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Coupled Simulation Process. (a) Scallion seedling position at simulation time 0 s. (b) Scallion seedling position at simulation time 3.5 s. (c) Scallion seedling position at simulation time 4.5 s. (d) Scallion seedling position at simulation time 6 s. (e) Scallion seedling position at simulation time 8.0 s.

Starting from 0 s, the planting mechanism catches the scallion seedlings and moves forward as a whole, while the planting disc rotates relative to the furrow opener. At 3.5 s, the planting disc rotates to the designated position, and the scallion seedlings begin to contact the soil. At 4.5 s, the scallion seedlings penetrate deep into the soil, and as contact with the soil and clamping force disappear, the scallion seedlings begin to detach from the planting disc. At 6 s, the scallion seedlings have completely detached from the planting disc and maintain a near-upright angle relative to the ground. As the machine advances, the soil-covering wheel covers the lower half of the seedlings with soil. At 8 s, the simulation process ends, and as the machine continues to move forward, the scallion seedlings are successfully buried in the soil. The simulation planting effect cross-section is shown in Figure 16. The planting depth is 5 cm, and the skew angle is less than 5°, which is in line with the expected test results.

Using the Design-Expert software, (Design-Expert 13 Stat-Ease Minneapolis, MN, USA) the results of the tests yielded the quadratic polynomial regression equations for Y1 and Y2, which were analyzed using variance and significance tests. The experimental results for transplant uprightness and compression force are shown in Table 15. The table shows that the model has extremely significant fitting, with X1, X2, X3, X2X3, X12, X22, and X32 having extremely significant effects on transplant uprightness, while the remaining factors have insignificant effects.

The analysis of variance for the radial compressive force Y2 in the table indicates that the model has extremely significant fit. X1, X2, X1X3, X12, X22, and X32 have significant effects, X3 has a significant effect, and the rest have insignificant effects. After removing the insignificant effect terms, the regression equations for Y1 and Y2 are as follows:

4.4. Response Surface Analysis

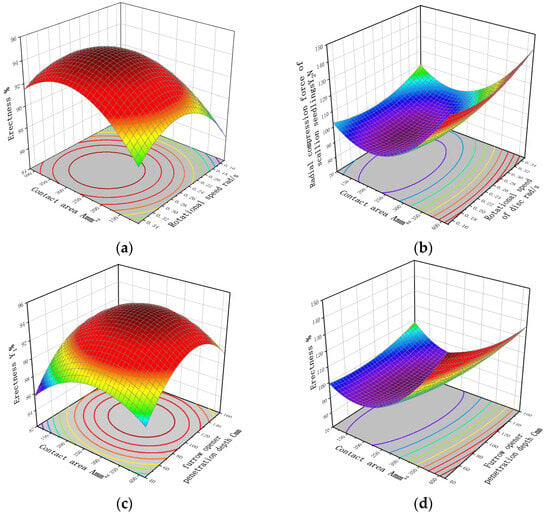

The response surfaces of parameter combinations that significantly influence the key evaluation indicators are presented in Figure 17. In Figure 17a, when the digging depth X3 is set at 100 mm, as the contact area between the scallion seedling and the disc and the disc speed gradually increase, the uprightness of the scallion seedling transplanted increases with the increase in speed and then gradually decreases. Regarding the contact area, if it is too small, the clamping force exerted by the flexible disc on the scallion seedling decreases, leading to deflection of the seedling at the clamping point. This further results in an excessively large soil penetration angle, which ultimately impairs the post-transplant uprightness.

Figure 17.

Influence of Interactive Factors on the Uprightness and Radial Compressive Force of Scallion Seedlings During Transplanting. (a) . (b) . (c) (d) .

As shown in Figure 17b, X3 remains unchanged. When the disc speed X2 takes a certain value, as the contact area X1 increases, the clamping force on the scallion seedlings gradually decreases due to the increase in flexible contact points. Later, as the flexible protrusions decrease and disappear, the scallion seedlings come into direct contact with the disc, and the clamping force on the scallion seedlings gradually increases. When X1 remains unchanged, as X2 increases, the resistance on the scallion seedlings increases, and Y2 shows an overall upward trend.

As shown in Figure 17c,d, when X2 is in a horizontal position and X1 remains unchanged, as X3 increases, the depth to which the scallion seedling is buried in the soil gradually increases, and the effect of the soil backfill force becomes more obvious, causing Y1 to first rise and then decrease.

4.5. Parameter Optimization

The objective function is optimized and solved, with the constraint conditions as shown in Equation (13).

The optimized parameter combination is obtained as follows: the clamping contact area of scallion seedlings is 255 mm2, the disc rotation speed is 0.25 rad/s, and the furrow opener penetration depth is 100 mm. However, during the field transplantation process, an excessively large clamping force will damage the scallion seedlings and affect the transplantation quality; an excessively deep or shallow furrow opening depth will cause the scallion seedlings to tilt forward or backward. Based on this, the optimal parameter combination of the solution is further optimized: the clamping contact area of scallion seedlings is 244.81 mm2, the disc rotation speed is 0.278 rad/s, the furrow opener penetration depth is 102.15 mm, the predicted [seedling uprightness rate] is 94.8%, the optimal clamping force is 90 N, and the damage rate of transplanted scallion seedlings is less than 3%.

4.6. Validation Test

To validate the design effectiveness, the parameters were further optimized: contact area of 244.8 mm2, disc rotation speed of 0.28 rad/s, and furrow opener penetration depth of 102.2 mm. Multiple experiments were conducted under the condition that other factors remained unchanged. The results showed that the average uprightness of the scallion seedlings was 94.4%, the average holding force of the scallion seedlings was 92 N, and the average damage rate was 2.91%. The test results were basically consistent with the optimization results and met the requirements for efficient and low-damage transplanting of scallions.

5. Field Trials

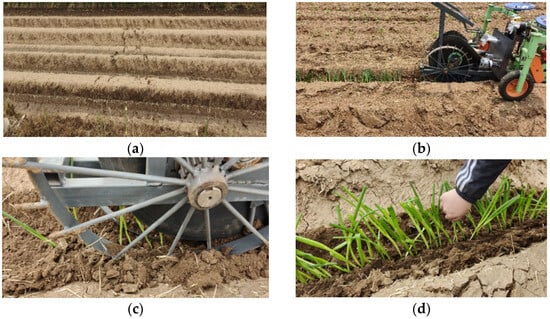

Field experiments were conducted in Zhangqiu District, Jinan City, Shandong Province in May 2025, using Zhangqiu scallions as the seedling variety. Before the experiments, furrowing and ridging work was carried out, with a furrow depth of 30 cm, furrow width of 75 cm, ridge width of 85 cm, and row spacing of 90 cm. The operating parameters of the machinery were consistent with the optimal solution obtained from the simulation, and the total travel distance was 30 m, as shown in Figure 18. A total of 10 test areas were set up, with each test area being 3 m in length and having a width equal to the furrow–ridge width. In accordance with the agronomic requirements for scallion cultivation, the planting spacing of scallion seedlings was 2–3 cm, the planting density was 32–33 plants per meter, and the number of seedlings planted in each test area was 96–100. Five test areas were randomly selected: the average seedling uprightness was measured by placing the base of a protractor parallel to the ground, and the damage status of the seedlings was observed and counted using the visual inspection method.

Figure 18.

Field Experiment on Scallion Seedling Transplanting. (a) Field trial site. (b) Machinery operation site. (c) Transplanting effect diagram. (d) Scallion seedling uprightness measurement.

It can be seen from Table 16 that the average uprightness of scallion seedlings in the field experiment was 93.8% and the damage rate was 2.7%. The errors between these results and the simulation experiment results were 1% and 0.3%, respectively, both of which were less than 2%. The scallion seedling planting area is a non-standardized operation environment, and the machinery is susceptible to various interference factors such as dynamic soil conditions and terrain changes during operation. At the same time, micro-topographic changes can cause vibrations when the machinery operates in the field, leading to tilting of seedlings when they fall. Additionally, in the actual experiment, it was impossible to ensure that every test seedling had the same diameter and length; although the seedling leaves were pruned, there were still a small number of seedlings with inconsistent traits, resulting in errors in the final experimental results. Furthermore, due to the limitations of the simulation software’s functions, the scene simulation could not fully reproduce the actual field operation conditions.

Table 16.

Seedling Uprightness and Damage Rate.

Although the above factors lead to deviations between the predicted values and the measured values, all deviations fall within the acceptable experimental error range. To further improve the planting uprightness and reduce the damage rate, improvements should focus on two aspects: (1) optimizing the mechanical stability and adding a shock absorption system to reduce mechanical vibrations; (2) adding a clamping force control system to flexibly adjust the clamping force of the elastic rollers, which is used to precisely control the pressure on the scallion seedlings and thereby reduce the seedling damage rate.

6. Conclusions

The research shows that optimizing the distribution of flexible protrusions on the edge of the flexible disc, the disc rotation speed, and the furrowing depth significantly improves the uprightness of scallion seedling transplanting and reduces the damage rate. The simulation analysis of the clamping point movement trajectory derived from the kinematic analysis of the planting disc is consistent with the research of Wang Y. [14], highlighting the impact of disc rotation speed on transplanting uprightness. Compared with the common fully automatic pot seedling transplanters [31], the machine designed in this study can realize both pot seedling and bare seedling transplanting by adjusting the width of the seedling belt, thus having a wider application range. Compared with the traditional semi-automatic transplanters [11], the machine designed in this study combines an automatic seedling feeding mechanism with a planting mechanism, which reduces the problems of high labor intensity, high seedling damage rate, and easy seedling leakage caused by manual seedling placement in traditional machinery.

In this study, an automatic transplanter suitable for bare seedling transplanting was designed and developed. The Hertz–Mindlin with Bonding contact model in the EDEM simulation software (EDEM 2022 Altair Engineering, Michigan, USA) was used to construct the scallion seedling model. Taking the actual maximum compressive force as the response value, the simulation approximation method was adopted to calibrate the parameters of the scallion seedling model. Through the Plackett–Burman experimental design, three factors with significant effects on the maximum compressive force were screened out: the normal/tangential contact stiffness of scallion seedlings, the normal/tangential ultimate stress of scallion seedlings, and the Poisson’s ratio of scallion seedlings. The steepest ascent experiment was used to narrow the calibration range of significant parameters. Several groups of optimal solutions were obtained through the Box–Behnken experiment and analysis of variance (ANOVA), and three groups of optimal solutions with the smallest relative error compared with the measured values of the scallion seedling compression experiment were determined. The normal/tangential contact stiffness of scallion seedlings, the normal/tangential ultimate stress of scallion seedlings, and the Poisson’s ratio of scallion seedlings were determined to be 4.842 × 109 N/m, 5.643 × 107 Pa, and 0.38, respectively. Based on these parameters, the discrete element model of the transplanting mechanism–scallion seedling–soil and the EDEM-ADAMS coupling model were established. A three-factor, three-level orthogonal simulation experiment was conducted to determine the optimal parameter combination of the transplanting mechanism during the transplanting process: flexible protrusions with a width of 40 mm distributed on the edge of the flexible disc, a flexible disc rotation speed of 0.278 rad/s, and a furrowing depth of 102.15 mm.

Field experiment results under optimal conditions show that when the transplanter moves forward at a speed of 0.06 m/s, the average uprightness of scallion seedling transplanting reaches 93.86% and the damage rate is 2.78%. The errors between these values and the predicted values are 1% and 0.3%, respectively, and the machine has good passability, meeting the agronomic requirements for scallion transplanting. Future research should prioritize improvements to the machine’s shock absorption components and seedling feeding components. In particular, by changing the material and size of the seedling belt, the seedling damage rate during the seedling feeding stage can be reduced to adapt to the transplanting of bare seedlings of different types and sizes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and H.L.; methodology, H.Z. and H.L.; software, Y.S. and X.Z.; validation, X.W. and H.L.; formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, X.W.; resources, H.L.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, X.Z.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R&D Program of China Grant No. “2024YFD2000400”, Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province “ZR2024ME137”, Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province “QKHZDZX[2024]004”, Agricultural science and technology innovation project of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences “CXGC2025B15”, Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Company of China National Tobacco Corporation “2024XM20”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed toward the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K. The Spectral Irradiance, Growth, Photosynthetic Characteristics, Antioxidant System, and Nutritional Status of Green Onion (Allium fistulosum L.) Grown Under Different Photo-Selective Nets. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 650471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yan, H.; Cui, W.; Chen, K.; Han, Z.; Bao, C. Research Situation and Analysis on Automatic Transplanting Technology for Vegetable Seedling. Agric. Eng. 2018, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, T.; Geng, A.; Li, Y.; Hou, J. Current situation and prospect of research on green Chinese Scallion planting machinery. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2018, 39, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, A.; Gural, M. A Study on Scallion Yield and Quality in Onion Genotypes According to Harvest Time. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2022, 31, 4684–4691. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; An, X.; Yan, B.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Meng, Z. Design and Experiment of Automatic Transplanter for Sweet Potato Naked Seedlings Based on Pretreatment Seedling Belt. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 53, 99–109. Available online: https://www.nyjxxb.net/index.php/journal/article/view/1497 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hourston, J.; Pérez, M.; Gawthrop, F.; Richards, M.; Steinbrecher, T.; Leubner-Metzger, G. The effects of high oxygen partial pressure on vegetable Allium seeds with a short shelf-life. Planta 2020, 251, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, S.; Colton, J. The Design of a Mechanized Onion Transplanter for Bangladesh with Functional Testing. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. Design of Cantilever Cup Vegetable Transplanter. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2011, 33, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Zhao, X.; Ye, B. Advancement of mechanized transplanting technology and equipments for field crops. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 1–20. Available online: http://www.j-csam.org/jcsamen/article/abstract/20220901?st=article_issue (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Yu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, B. Current situation and prospect of transplanter. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 44–53. Available online: http://www.j-csam.org/jcsamen/article/abstract/20140808 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Niu, Z.; Li, T.; Wu, Y.; Xi, R.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Hou, J. Design and Optimization of Planting Process Parameters for 2ZYX-2 Type Green Onion Ditching and Transplanting Machine. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 89, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Feng, J.; Zeng, A. Design and Experimental Research of Scallion Transplanter. J. Heilongjiang August First Land Reclam. Univ. 2006, 18, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, L. Development of The Chain Clamp Type Spring Scallion Transplanting Machine. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Su, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Cheng, X.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Z.; et al. Design and study of anti-blocking type potato stubble disc clamping and pulling device based on MBD-DEM coupled simulation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, F. Parameter optimization and test of harvesting device for digging and pulling green onions based on discrete element analysis. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2025, 18, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Jiang, R.; Mai, C.; Ma, Z.; He, H. Research on the ditching resistance reduction of self-excited vibrations ditching device based on MBD-DEM coupling simulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1372585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Guo, F.; Guan, R.; Li, H.; Tang, H.; Wang, Q. Mechanism Analysis and Experimental Verification of Side-Filled Rice Precision Hole Direct Seed-Metering Device Based on MBD-DEM Simulations. Agriculture 2024, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, J. Development of a variable-diameter threshing drum for rice combine harvester using MBD—DEM coupling simulation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, G.; Yu, Z.; You, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, B.; Gao, X. Design and experiment of type 2ZGF-2 duplex sweet potato transplanter. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. Design and Experimental Study on a Screw-Type Seedling Separating Device for Welsh Scallion Transplanter. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Bai, Z.; Li, Z.; Xie, D.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. Straw/Spring Teeth Interaction Analysis of Baler Picker in Smart Agriculture via an ADAMS-DEM Coupled Simulation Method. Machines 2021, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W.; Yang, W.; Li, T.; Chang, C.; Ren, W.; Lei, X. Distribution characteristics and parameter optimisation of an air-assisted centralised seed-metering device for rapeseed using a CFD-DEM coupled simulation. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 208, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ran, X.; Shi, L.; Xing, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, S.; Li, H. Simulation and Optimization of a Rotary Cotton Precision Dibbler Using DEM and MBD Coupling. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yan, L.; Jiang, D.; Gou, H.; Fu, X.; Zhang, J. Establishment and Research of Cotton Stalk Moisture Content-Discrete Element Parameter Model Based on Multiple Verification. Processes 2024, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, K. The impact of ‘T’-shaped furrow opener of no-tillage seeder on straw and soil based on discrete element method. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wu, Y.; Hou, J. Design and Optimization of a Machine-Vision-Based Complementary Seeding Device for Tray-Type Green Onion Seedling Machines. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikins, K.; Ucgul, M.; Barr, J.; Awuah, E.; Antille, D.; Jensen, T.; Desbiolles, J. Review of Discrete Element Method Simulations of Soil Tillage and Furrow Opening. Agriculture 2023, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, X.; Geng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, T. Design and experiment of furrow side pick-up soil blade for wheat strip-till planter using the discrete element method. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 55, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, M.; Chen, W.; Yuan, D.; Wu, C.; Zhu, J. Simulation Analysis and Experiments for Blade-Soil-Straw Interaction under Deep Ploughing Based on the Discrete Element Method. Agriculture 2023, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, X.; Wei, Z.; Geng, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, K.; Bai, M. Determination and verification of parameters for the discrete element modelling of single disc covering of flexible straw with soil. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 233, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Gao, M.; Li, T.; Niu, Z.; Hou, J.; Li, G. Design and Experiment of a High-efficiency and Low-loss Automatic Transplanter for Scallion. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2021, 43, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).