Endoscopic Reflux Esophagitis and Reflux-Related Symptoms after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy: Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search and Data Extraction

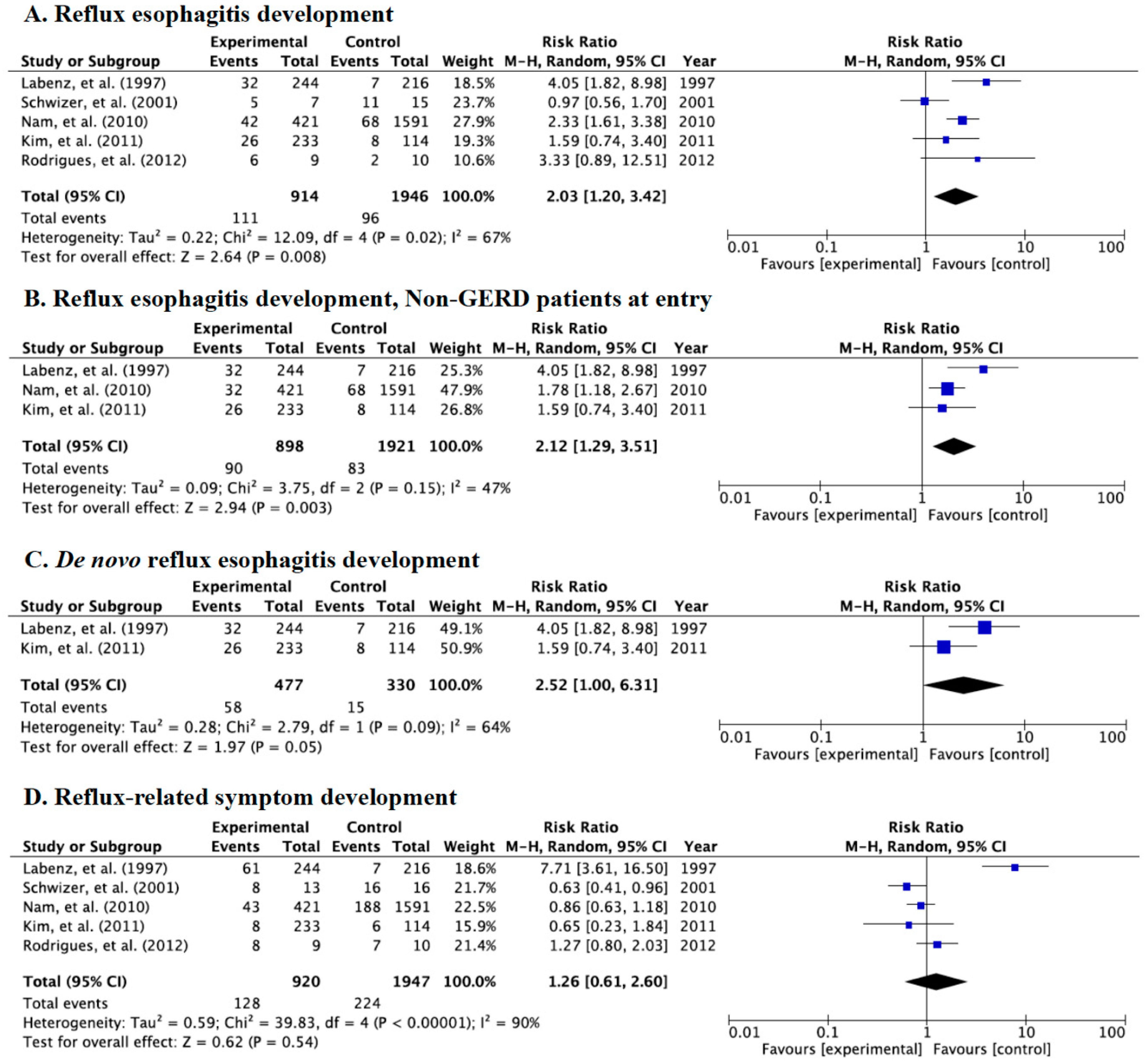

3.2. Meta-Analysis for Incidence Rate of Reflux Esophagitis, de novo Esophagitis, and Symptoms

3.3. Meta-Analysis for the Incidence Rate of Reflux Esophagitis and Symptoms in Category A

3.4. Meta-Analysis for Incidence Rate of Reflux Esophagitis and Symptoms in Category B

3.5. Meta-Analysis for Incidence Rate of Reflux Esophagitis and Symptoms in Category C

3.6. Meta-Analysis for the Incidence Rate of de novo Reflux Esophagitis and Symptoms between Western and East Asian Populations

4. Discussion

4.1. Acid secretion after H. pylori Eradication Therapy

4.2. Development of Reflux Esophagitis after Eradication Therapy

4.3. Difference of Risk of Reflux Esophagitis after Eradication Therapy between East Asian and Western Populations

4.4. Development of Reflux-Related Symptoms after Eradication Therapy

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kinoshita, Y.; Kawanami, C.; Kishi, K.; Nakata, H.; Seino, Y.; Chiba, T. Helicobacter pylori independent chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese. Gut 1997, 41, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Arakawa, T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; O’Morain, C.; Gisbert, J.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Axon, A.T.; Bazzoli, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Atherton, J.; Graham, D.Y.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—The Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2016, 66, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghunath, A.; Hungin, A.P.S.; Wooff, D.; Childs, S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Systematic review. Br. Med. J. 2003, 326, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremonini, F.; Di Caro, S.; Delgado-Aros, S.; Sepulveda, A.; Gasbarrini, G.; Camilleri, M. Meta-analysis: The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.; Uotani, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Andoh, A.; Furuta, T. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Time Covering Eradication for All Patients Infected with Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Digestion 2016, 93, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Befrits, R.; Sjöstedt, S.; Ödman, B.; Sörngård, H.; Lindberg, G. Curing Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer does not provoke gastroesophageal reflux disease. Helicobacter 2000, 5, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytzer, C.A.P. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori Compared with Long-Term Acid Suppression in Duodenal Ulcer Disease: A Randomized Trial with 2-Year Follow-up. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 35, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Bardhan, C.; Young, L.; Dixon, M.F.; Brown, L.; Axon, A.T. Helicobacter pylori eradication does not exacerbate reflux symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2001, 121, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.; Wong, S.K.H.; Lee, Y.T.; Leung, W.K.; Sung, J.J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on oesophageal acid exposure in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Leung, W.K.; Hui, Y.; Leong, R.W.; Chung, S.C.S.; Sung, J.J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A double blind, placebo controlled, randomised trial. Gut 2004, 53, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupcinskas, L.; Jonaitis, L.; Kiudelis, G. A 1 year follow-up study of the consequences of Helicobacter pylori eradication in duodenal ulcer patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 16, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, R.F.; Lane, J.A.; Murray, L.J.; Harvey, I.M.; Donovan, J.L.; Nair, P. Randomised controlled trial of effects of Helicobacter pylori infection and its eradication on heartburn and gastro-oesophageal reflux: Bristol helicobacter project. Br. Med. J. 2004, 328, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ott, E.A.; Mazzoleni, L.E.; Edelweiss, M.I.; Sander, G.B.; Wortmann, A.C.; Theil, A.L.; Somm, G.; Cartell, A.; Rivero, L.F.; Uchôa, D.M.; et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication does not cause reflux oesophagitis in functional dyspeptic patients: A randomized, investigator-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, N.; Talley, N.J.; Stolte, M.; Sundin, M.; Junghard, O.; Bolling-Sternevald, E. Patterns of gastritis and the effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Western patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 24, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonaitis, L.; Kiudelis, G.; Kupcinskas, L. Gastroesophageal reflux disease after Helicobacter pylori eradication in gastric ulcer patients: A one-year follow-up study. Medicina 2008, 44, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonaitis, L.; Kupčinskas, J.; Kiudelis, G.; Kupčinskas, L. De novo erosive esophagitis in duodenal ulcer patients related to pre-existing reflux symptoms, smoking, and patient age, but not to Helicobacter pylori eradication: A one-year follow-up study. Medicina 2010, 46, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwizer, W.; Menne, D.; Schütze, K.; Vieth, M.; Goergens, R.; Malfertheiner, P.; Leodolter, A.; Fried, M.; Fox, M.R. The effect of Helicobacter pylori infection and eradication in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2013, 1, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallone, C.A.; Barkun, A.N.; Friedman, G.; Mayrand, S.; Loo, V.; Beech, R.; Best, L.; Joseph, L. Is Helicobacter pylori eradication associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, N.; Hahn, B.; McSorley, D. Recurrent symptoms and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with duodenal ulcer treated for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 14, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, K.E.; Dickson, A.; El-Nujumi, A.; El–Omar, E.M.; Kelman, A. Symptomatic benefit 1-3 years after h. pylori eradication in ulcer patients: Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, K.H. No protective role of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis in patients with duodenal or benign gastric ulcer in Korea. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001, 46, 2724–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Dent, J.; Zeijlon, L.; Sipponen, P.; Van Zanten, S.J.O.V.; Burman, C.-F.; Lind, T.; Wrangstadh, M.; Bayerdörffer, E.; Lonovics, J. Impact of Helicobacter pylori eradication on heartburn in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease—Results from a randomized trial programme. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 1431–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, L.; Sugg, J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on development of erosive esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: A post hoc analysis of eight double blind prospective studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 2992–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaira, D.; Vakil, N.; Rugge, M.; Gatta, L.; Ricci, C.; Menegatti, M.; Leandro, G.; Holton, J.; Russo, V.M.; Miglioli, M. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on development of dyspeptic and reflux disease in healthy asymptomatic subjects. Gut 2003, 52, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, K.; Katoh, H.; Miyazaki, T.; Fukuchi, M.; Kuwano, H.; Kimura, H.; Fukai, Y.; Inose, T.; Motojima, T.; Toda, N.; et al. Factors Associated with the Development of Reflux Esophagitis After Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006, 51, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take, S.; Mizuno, M.; Ishiki, K.; Nagahara, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yokota, K.; Oguma, K.; Okada, H.; Yamamoto, K. Helicobacter pylori eradication may induce de novo, but transient and mild, reflux esophagitis: Prospective endoscopic evaluation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhou, L.-Y.; Lin, S.-R.; Hou, X.-H.; Li, Z.-S.; Chen, M.-H.; Yan, X.-E.; Meng, L.-M.; Zhang, J.; Lü, J.-J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Reflux Esophagitis Therapy. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labenz, J.; Blum, A.L.; Bayerdörffer, E.; Meining, A.; Stolte, M.; Börsch, G. Curing Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer may provoke reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1997, 112, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwizer, W.; Thumshirn, M.; Dent, J.; Guldenschuh, I.; Menne, D.; Cathomas, G.; Fried, M. Helicobacter pylori and symptomatic relapse of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001, 357, 1738–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.Y.; Choi, I.J.; Ryu, K.H.; Kim, B.C.; Kim, C.G.; Nam, B.-H. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Its Eradication on Reflux Esophagitis and Reflux Symptoms. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, J.I.; Baik, G.H.; Kim, S.J.; Seo, G.S.; Oh, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Jeong, H.; Hong, S.J.; et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on the Development of Refl ux Esophagitis and Gastroesophageal Refl ux Symptoms: A Nationwide Multi-Center Prospective Study. Gut Liver 2011, 5, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L., Jr.; De Faria, C.M.; Geocze, S.; Chehter, L. Helicobacter pylori eradication does not influence gastroesophageal reflux disease: A prospective, parallel, randomized, open-label, controlled trial. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2012, 49, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, T.; Cui, X.-B.; Zheng, H.; Chen, D.; He, L.; Jiang, B. Meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Cui, W.; Ge, J.; Lin, L. The Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy on the Development of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 349, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.M.; Choudhary, A.; Bechtold, M.L. Effect of Helicobacter pylor itreatment on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 47, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Ma, S.; Shang, L.; Qian, J.; Zhang, G. Effects of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Helicobacter 2011, 16, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoobi, M.; Farrokhyar, F.; Yuan, Y.; Hunt, R.H. Is There an Increased Risk of GERD After Helicobacter pylori Eradication? A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, A.S.; Hungin, A.P.S.; Wooff, D.; Childs, S. The effect of Helicobacter pylori and its eradication on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with duodenal ulcers or reflux oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 20, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenszel, W.; Mantel, N. Statistical Aspects of the Analysis of Data from Retrospective Studies of Disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1959, 22, 719–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, J.A.; Laird, N.M.; Sacks, H.S.; Chalmers, T.C. A comparison of statistical methods for combining event rates from clinical trials. Stat. Med. 1989, 8, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N.M. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 45, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uotani, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Nishino, M.; Kodaira, C.; Yamade, M.; Sahara, S.; Yamada, T.; Osawa, S.; Sugimoto, K.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Ability of Rabeprazole to Prevent Gastric Mucosal Damage From Clopidogrel and Low Doses of Aspirin Depends on CYP2C19 Genotype. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 879–885.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, M.; Furuta, T.; Shirai, N.; Kajimura, M.; Hishida, A.; Sakurai, M.; Ohashi, K.; Ishizaki, T. Different dosage regimens of rabeprazole for nocturnal gastric acid inhibition in relation to cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype status. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 76, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, T.; El–Omar, E.M.; Xiao, F.; Shirai, N.; Takashima, M.; Sugimurra, H. Interleukin 1β polymorphisms increase risk of hypochlorhydria and atrophic gastritis and reduce risk of duodenal ulcer recurrence in Japan. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.; Ohno, T.; Yamaoka, Y. Expression of angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptor mRNAs in the gastric mucosa of Helicobacter pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolfe, M.; Nompleggi, D. Cytokine inhibition of gastric acid secretion—A little goes a long way. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 2177–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El–Omar, E.M.; Penman, I.D.; Ardill, J.E.; Chittajallu, R.S.; Howie, C.; McColl, K.E. Helicobacter pylori infection and abnormalities of acid secretion in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Gastroenterology 1995, 109, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, T.; Ohara, S.; Sekine, H.; Iijima, K.; Kato, K.; Toyota, T.; Shimosegawa, T. Increased gastric acid secretion after Helicobacter pylori eradication may be a factor for developing reflux oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.; Haruma, K.; Mihara, M.; Kamada, T.; Yoshihara, M.; Sumii, K.; Kajiyama, G.; Kawanishi, M. High incidence of reflux oesophagitis after eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori: Impacts of hiatal hernia and corpus gastritis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 14, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, Y.; Orito, E.; Mizokami, M.; Gutiérrez, Ó.; Saitou, N.; Kodama, T.; Osato, M.S.; Kim, J.G.; Ramirez, F.C.; Mahachai, V.; et al. Helicobacter pylori in North and South America before Columbus. FEBS Lett. 2002, 517, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Country | Disease | Follow-up Period (months) | Number of Patients/Controls (n/n) | Patient Sex (M/F) | Patient Age (year) | Patient Smoking (n/n) | Patient Alcohol (n/n) | Outcome | Eradication Regimen | Eradication Rate (Patients) (%, (n/n)) | Eradication Rate (Control) (%, (n/n)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category A | ||||||||||||

| Befrits et al. (2000) [7] | Norway | DU | 24 | 110/55 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | O (40)/A (750), 2 weeks | 49/110 (44.5%) | 1/55 (1.8%) |

| Bytzer et al. (2000) [8] | Denmark | DU | 24 | 139/137 | 104/35 | 53.4 ± 13.0 | 67/139 | NA | de novo | O (20)/A (750, t)/M (500, t), 2 weeks | 84/139 (60.4%) | NA |

| Moayyedi et al. (2001) [9] | England | GERD | 12 | 93/97 | 38/47 | 47.4 ± 12.5 | 27/85 | 56/85 | de novo | O (20)/Tinidazole (500)/C (250), 1 week | 70/85 (82.4%) | 12/93 (12.9%) |

| Wu et al. (2002) [10] | Hong Kong | RR | 4 | 14/11 | 9/5 | 51.3 ± 12.3 | 2/14 | NA | Recurrent | O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 14/14 (100%) | NA |

| Wu et al. (2004) [11] | Hong Kong | GERD | 12 | 53/51 | 26/27 | 54.0 ± 13.8 | 7/53 | 10/53 | Recurrent | O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 52/53 (98.1%) | 2/51 (3.9%) |

| Kupcinskas et al. (2004) [12] | Lithuania | DU | 12 | 163/42 | 106/57 | 41.6 ± 13.2 | 73/163 | NA | de novo | R (300)/A (1000)/M (400), 2 weeks or FAM (40)/A (1000)/M (400), 2 weeks, or O (20)/C (250)/M (400), 1 week, or O (20)/A (1000)/M (800), 1 week, or O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 92/163 (56.4%) | NA |

| Harvey et al. (2004) [13] | England | Gastritis | 24 | 787/771 | 385/402 | NA | 362/767 | 140/767 | de novo | Ranitidine bismuth (400)/C (500), 2 weeks | 659/727 (90.6%) | 99/706 (14.0%) |

| Ott et al. (2005) [14] | Brazil | FD | 12 | 82/75 | 18/64 | 41.5 ± 12.0 | 17/82 | 10/82 | de novo | L (30)/A (1000)/C (500), 10 days | 74/82 (90.2%) | 1/75 (1.3%) |

| Vakil et al. (2006) [15] | Western | FD | 12 | 297/306 | 116/181 | 49 ± 14 | 77/297 | NA | de novo | O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 243/297 (81.8%) | 10/306 (3.7%) |

| Jonaitis et al. (2008) [16] | Lithuania | GU | 12 | 54/34 | 27/17 | 51.3 ± 13.7 | 14/44 | NA | de novo | O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week or O (20)/A (1000)/M (400), 1 week or ranitidine (300)/A (1000)/C (500), 2 weeks | 25/44 (56.8%) | 0/25 (0%) |

| Jonaitis et al. (2010) [17] | Lithuania | DU | 12 | 119/31 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week or O (20)/A (1000)/M (400), 1 week or ranitidine (300)/A (1000)/C (500), 2 weeks | 70/119 (58.8%) | 0/31 (0%) |

| Schwizer et al. (2013) [18] | Europe | GERD | 2.7 | 100/98 | NA | 49 (20–75) | NA | NA | Recurrent | E (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 59/100 (59.0%) | NA |

| Category B | ||||||||||||

| Fallone et al. (2000) [19] | Canada | DU | 12 | 63/34 | 45/18 | 48 ± 14 | 22/63 | 35/63 | de novo | Bismuth/M/A or Bismuth/M or M | 63/87 (72.4%) | |

| Vakil et al. (2000) [20] | USA | DU | 12 | 64/178 | 56/8 | 49 ± 12 | 17/64 | 19/64 | de novo | Ranitidine bismuth/C or Ranitidine bismuth/A | 64/242 (26.4%) | |

| McColl et al. (2000) [21] | Scotland | PU | 6 | 86/11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | O (20)/M (400, t)/A (500, t) or O (20)/M (400, t)/TC (500, t), 2 weeks | 70/97 (72.2%) | |

| Kim et al. (2001) [22] | Korea | PU | 24 | 125/61 | 105/20 | NA | 75/125 | 79/125 | de novo | O (20)/A (750)/C (200), 1–2 weeks | 125/186 (67.2%) | |

| Malfertheiner et al. (2002) [23] | Germany | PU | 6 | 369/993 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | O (20)/A (1000)/C (500) or O (20)/M (400)/C (250) or O (20)/A (1000)/M (400) or A (1000)/C (500) or M (400)/C (250), 7 days | 369/1421 (26.9%) | |

| Laine et al. (2002) [24] | USA | DU | 8 | 621/544 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | O (40)/A (500, t), 2 weeks or O (20)/A (1000, t), 2 weeks or O (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 10 days or E (40)/A (1000)/C (500), 10 days or E (40)/C (500), 10 days or E (40)/A (1000)/C (500), 10 days | 621/1165 (53.3%) | |

| Vaira et al. (2003) [25] | Italy | Gastritis | 102 | 81/88 | 56/25 | 47 ± 12 | 9/81 | 15/81 | de novo | Unknown | 81/169 (47.9%) | |

| Tsukada et al. (2006) [26] | Japan | PU | 48 | 119/34 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | L (30)/A (750)/C (200 or 400), 1 week | 119/163 (73.0%) | |

| Take et al. (2009) [27] | Japan | PU | 43 | 1000/187 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | O (20)/A (750)/C (200 or 400) or L (30)/A (750)/C (200 or 400) or R (10)/A (750)/C (200 or 400), 1 week | NA | |

| Xue et al. (2015) [28] | China | RR | 2 | 92/84 | 69/23 | 48.3 ± 13.0 | 23/69 | 16/76 | Healing | E (20)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week, or sequential regimen (E/A + E/C/tinidazole), 10 days | 92/176 (52.3%) | |

| Category C | ||||||||||||

| Labenz et al. (1997) [29] | Germany | DU | 17 | 244/216 | 155/92 | 52.9 ± 14.5 | 115/244 | 81/244 | de novo | Unknown | 244/460 (53.0%) | |

| Schwizer et al. (2001) [30] | Switzerland | GERD | 6 | 13/16 | 2/11 | 54 ± 9 | NA | NA | Recurrent | L (30)/A (1000)/C (500), 10 days | 13/20 (65.0%) | |

| Nam et al. (2010) [31] | Korea | RR | 24 | 465/1591 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | L (30)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 421/548 (76.8%) | |

| Kim et al. (2011) [32] | Korea | PU | 24 | 233/114 | NA | NA | NA | NA | de novo | 1st, PPI/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week, 2nd, E (20)/bismuthate (300, q)/M (500, t)/TC (500, q), 1–2 weeks | 233/347 (67.1%) | |

| Rodrigues et al. (2012) [33] | Brazil | GERD | 3 | 9/10 | 6/3 | 37.4 ± 12.5 | NA | 3/9 | de novo | L (30)/A (1000)/C (500), 1 week | 9/11 (81.8%) |

| Authors (Year) | Number of Patients at Entry (n) | Number of Patients with RR at Entry (% (n/n)) | Number of Patients with RR Development after Eradication (% (n/n)) | Number of Patients with de novo RR Development after Eradication (n) | Number of Patients with Symptoms at Entry (% (n/n)) | Number of Patients with Symptoms after Eradication (% (n/n)) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eradicated | Control | Eradicated | Control | Eradicated | Control | Eradicated | Control | Eradicated | Control | Eradicated | Control | |

| Category A | ||||||||||||

| Befrits et al. [7] | 94 | 51 | 9% (0/94) | 0% (0/51) | 10.1% (8/79) | 7.6% (5/66) | 10.1% (8/79) | 7.6% (5/66) | NA | NA | 27.8% (22/79) | 43.9% (29/66) |

| Bytzer et al. [8] | 139 | 137 | 7.2% (10/139) | 5.8% (8/137) | 8.5% (6/71) | 3.8% (3/80) | 2.8% (2/71) | 3.8% (3/80) | 28.1% (39/139) | 25.5% (35/137) | 9.9% (7/71) | 8.8% (7/80) |

| Moayyedi et al. [9] | 85 | 93 | 23.5% (20/85) | 20.4% (19/93) | 10.5% (4/38) | 4.7% (2/43) | NA | NA | 100% (85/85) | 100% (93/93) | 17.6% (15/85) | 16.1% (15/93) |

| Wu et al. [10] | 14 | 11 | 100% (14/14) | 100% (11/11) | 78.6% (11/14) | 72.7% (8/11) | NA | NA | 100% (14/14) | 100% (11/11) | NA | NA |

| Wu et al. [11] | 53 | 51 | 28.3% (15/53) | 31.4% (16/51) | 9.4% (5/53) | 0% (0/51) | 0% (0/53) | 0% (0/51) | 100% (53/53) | 100% (51/51) | 28.3% (15/53) | 15.7% (8/51) |

| Kupcinskas et al. [12] | 163 | 42 | 27.0% (44/163) | 26.2% (11/42) | 26.3% (43/163) | 20.9% (9/43) | 4.3% (7/163) | 4.7% (2/43) | 47.2% (77/163) | 40.5% (17/42) | 29.4% (48/163) | 32.6% (14/43) |

| Harvey et al. [13] | 708 | 702 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 53.4% (378/708) | 52.4% (368/702) | 23.9% (169/708) | 24.2% (170/702) |

| Ott et al. [14] | 82 | 75 | 0% (0/82) | 0% (0/75) | 11.0% (8/73) | 11.7% (7/60) | 11.0% (8/73) | 11.7% (7/60) | 54.9% (45/82) | 48.0% (36/75) | 50.7% (37/73) | 51.7% (31/60) |

| Vakil et al. [15] | 297 | 306 | 2.7% (8/297) | 1.6% (5/306) | 6.5% (15/232) | 2.2% (5/227) | 5/6% (13/232) | 2.2% (5/227) | 75.8% (225/297) | 75.2% (230/306) | 63.4% (151/238) | 63.3% (145/229) |

| Jonaitis et al. [16] | 44 | 25 | 18.2% (8/44) | 16.0% (4/25) | 12.0% (3/25) | 17.2% (5/29) | NA | NA | 18.2% (8/44) | 16.0% (4/25) | 12.0% (3/25) | 26.3% (5/19) |

| Jonaitis et al. [17] | 119 | 31 | 0% (0/119) | 0% (0/31) | 14.3% (17/119) | 6.5% (2/31) | 14.3% (17/119) | 6.5% (2/31) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Schwizer et al. [18] | 72 | 67 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 58.3% (42/72) | 52.2% (37/67) |

| Category B | ||||||||||||

| Fallone et al. [19] | 63 | 24 | 0% (0/63) | 0% (0/24) | 20.6% (13/63) | 4.2% (1/24) | 20.6% (13/63) | 4.2% (1/24) | 0% (0/63) | 0% (0/24) | 28.6% (18/63) | 8.3% (2/24) |

| Vakil et al. [20] | 64 | 178 | 0% (0/64) | 0% (0/178) | 0% (0/51) | 0% (0/161) | 0% (0/51) | 0% (0/161) | 57.8% (37/64) | 51.7% (92/178) | 23.5% (12/51) | 25.5% (41/161) |

| McColl et al. [21] | 86 | 11 | 0% (0/86) | 0% (0/11) | 5.8% (5/86) | 0% (0/11) | 5.8% (5/86) | 0% (0/11) | 0% (0/86) | 0% (0/11) | 23.8% (15/63) | 8.6% (3/35) |

| Kim et al. [22] | 125 | 61 | 0% (0/125) | 0% (0/61) | 4.0% (5/125) | 8.2% (5/61) | 4.0% (5/125) | 8.2% (5/61) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Malfertheiner et al. [23] | 369 | 993 | 0.6% (1/162) | 0.9% (1/107) | 3.1% (5/162) | 1.9% (2/107) | 2.5% (4/162) | 1.9% (2/107) | 33.5% (333/993) | 40.7% (150/369) | 12.1% (120/993) | 23.6% (87/369) |

| Laine et al. [24] | 621 | 544 | 0% (0/621) | 0% (0/544) | 7.1% (2/28) | 6.6% (5/76) | 7.1% (2/28) | 6.6% (5/76) | 0% (0/621) | 0% (0/544) | 14.1% (13/92) | 20.0% (7/35) |

| Vaira et al. [25] | 81 | 88 | 0% (0/81) | 0% (0/88) | 28.8% (21/73) | 18.9% (14/74) | 28.8% (21/73) | 18.9% (14/74) | 0% (0/81) | 0% (0/88) | 1.4% (1/74) | 14.0% (12/86) |

| Tsukada et al. [26] | 119 | 34 | 0% (0/119) | 0% (0/34) | 20.2% (24/119) | 26.5% (9/34) | 11.8% (14/119) | 26.5% (9/34) | 0% (0/119) | 0% (0/34) | NA | NA |

| Take et al. [27] | 1000 | 187 | 0% (0/1000) | 0% (0/187) | 27.9% (279/1000) | 13.9% (26/187) | 27.9% (279/1000) | 13.9% (26/187) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Xue et al. [28] | 92 | 84 | 100% (92/92) | 100% (84/84) | 19.6% (18/92) | 20.2% (17/84) | NA | NA | 100% (92/92) | 100% (84/84) | NA | NA |

| Category C | ||||||||||||

| Labenz et al. [29] | 244 | 216 | 0% (0/244) | 0% (0/216) | 13.1% (32/244) | 3.2% (7/216) | 13.1% (32/244) | 3.2% (7/216) | 29.9% (73/244) | NA | 25.0% (61/244) | 3.2% (7/216) |

| Schwizer et al. [30] | 13 | 16 | NA | NA | 71.4% (5/7) | 73.3% (11/15) | NA | NA | 61.5% (8/13) | 100% (16/16) | 61.5% (8/13) | 100% (16/16) |

| Nam et al. [31] | 421 | 1591 | 4.0% (17/421) | 2.9% (46/1591) | 10.0% (42/421) | 4.3% (68/1591) | NA | NA | 6.7% (28/421) | 6.2% (99/1591) | 10/2% (43/421) | 11.8% (188/1591) |

| Kim et al. [32] | 233 | 114 | 0% (0/233) | 0% (0/114) | 11.2% (26/233) | 7.0% (8/114) | 11.2% (26/233) | 7.0% (8/114) | 0% (0/233) | 0% (0/114) | 3.4% (8/233) | 5.3% (6/114) |

| Rodrigues et al. [33] | 9 | 10 | 55.6% (5/9) | 50% (5/10) | 66.7% (6/9) | 20.0% (2/10) | NA | NA | 100% (9/9) | 100$ (10/10) | 88.9% (8/9) | 70.0% (7/10) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sugimoto, M.; Murata, M.; Mizuno, H.; Iwata, E.; Nagata, N.; Itoi, T.; Kawai, T. Endoscopic Reflux Esophagitis and Reflux-Related Symptoms after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy: Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9093007

Sugimoto M, Murata M, Mizuno H, Iwata E, Nagata N, Itoi T, Kawai T. Endoscopic Reflux Esophagitis and Reflux-Related Symptoms after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy: Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(9):3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9093007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSugimoto, Mitsushige, Masaki Murata, Hitomi Mizuno, Eri Iwata, Naoyoshi Nagata, Takao Itoi, and Takashi Kawai. 2020. "Endoscopic Reflux Esophagitis and Reflux-Related Symptoms after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy: Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 9: 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9093007

APA StyleSugimoto, M., Murata, M., Mizuno, H., Iwata, E., Nagata, N., Itoi, T., & Kawai, T. (2020). Endoscopic Reflux Esophagitis and Reflux-Related Symptoms after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy: Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9093007