Randomised Clinical Trial: Calorie Restriction Regimen with Tomato Juice Supplementation Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Preserves a Proper Immune Surveillance Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T-Lymphocytes in Obese Children Affected by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

- -

- Age 4–14 years

- -

- BMI > 85th percentile

- -

- Liver steatosis evaluated as mild, moderate or severe by US (hyperechogenic liver tissue compared with the adjacent kidney cortex)

- -

- Other liver disease, such as viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency

- -

- Diabetes or manifest metabolic alterations

- -

- Other associated disease

2.2. Assessment of Anthropometric Status

2.3. Serum Lycopene Determination

2.4. Oxidative Stress Determination.

2.5. Ultrasound Monitoring

- (1)

- Normal liver echo texture (absence of steatosis).

- (2)

- Presence of hyperechogenic liver tissue (compared with the adjacent kidney cortex) with fine and tightly packed echo targets and of normal beam penetration with normal visualization of diaphragm and portal vein borders was considered as mild steatosis.

- (3)

- Moderate and diffuse increase of echo intensity with decreased beam penetration (with slightly decreased visualization of diaphragm) associated with a decrease in visualization of silhouetting of the portal vein borders was considered as moderate steatosis.

- (4)

- Marked increase in echoes intensity with no visualization of portal vein border, obscured diaphragm and posterior portion of the right lobe, and reduced visibility of kidney was considered as severe steatosis.

2.6. Measurement of Plasma Cytokine Levels

2.7. Immunophenotypic and Flow Cytometry Analyses

2.8. T cell Cultures

2.9. Bioenergetics and Metabolism of T Lymphocytes

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Diet

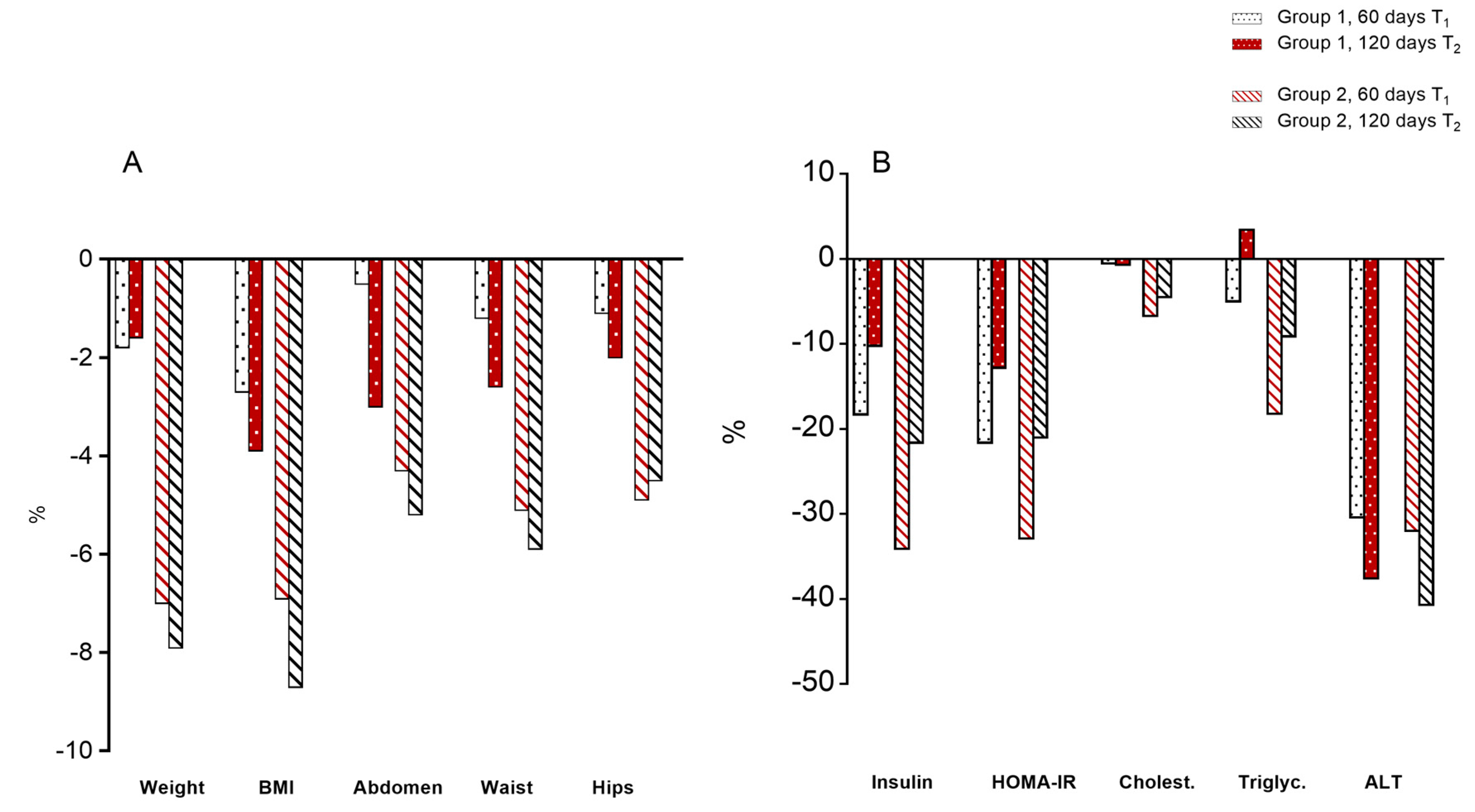

3.2. Body Parameters

3.3. Serum Parameters

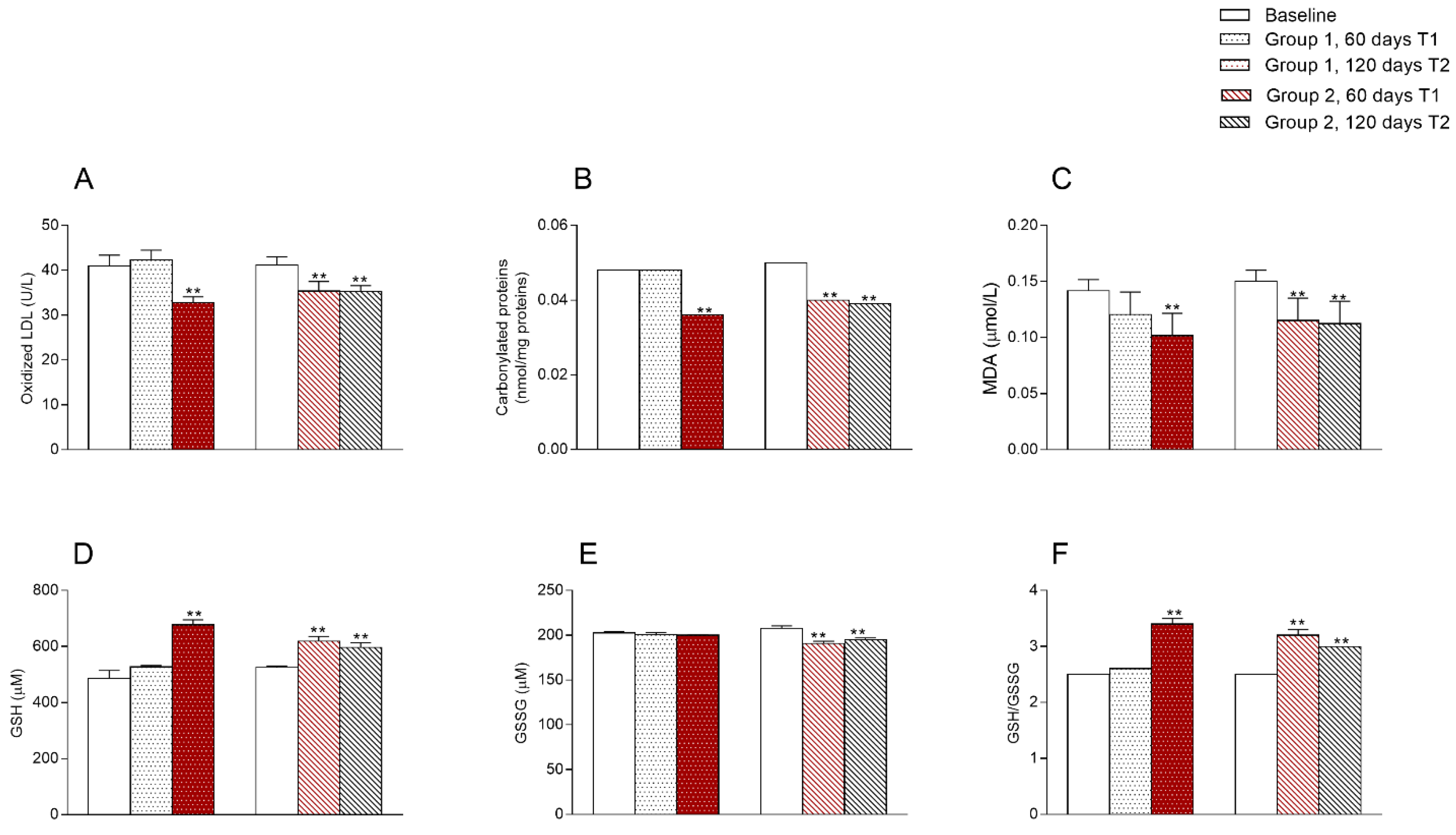

3.4. Oxidative State

3.5. Ultrasound Parameters

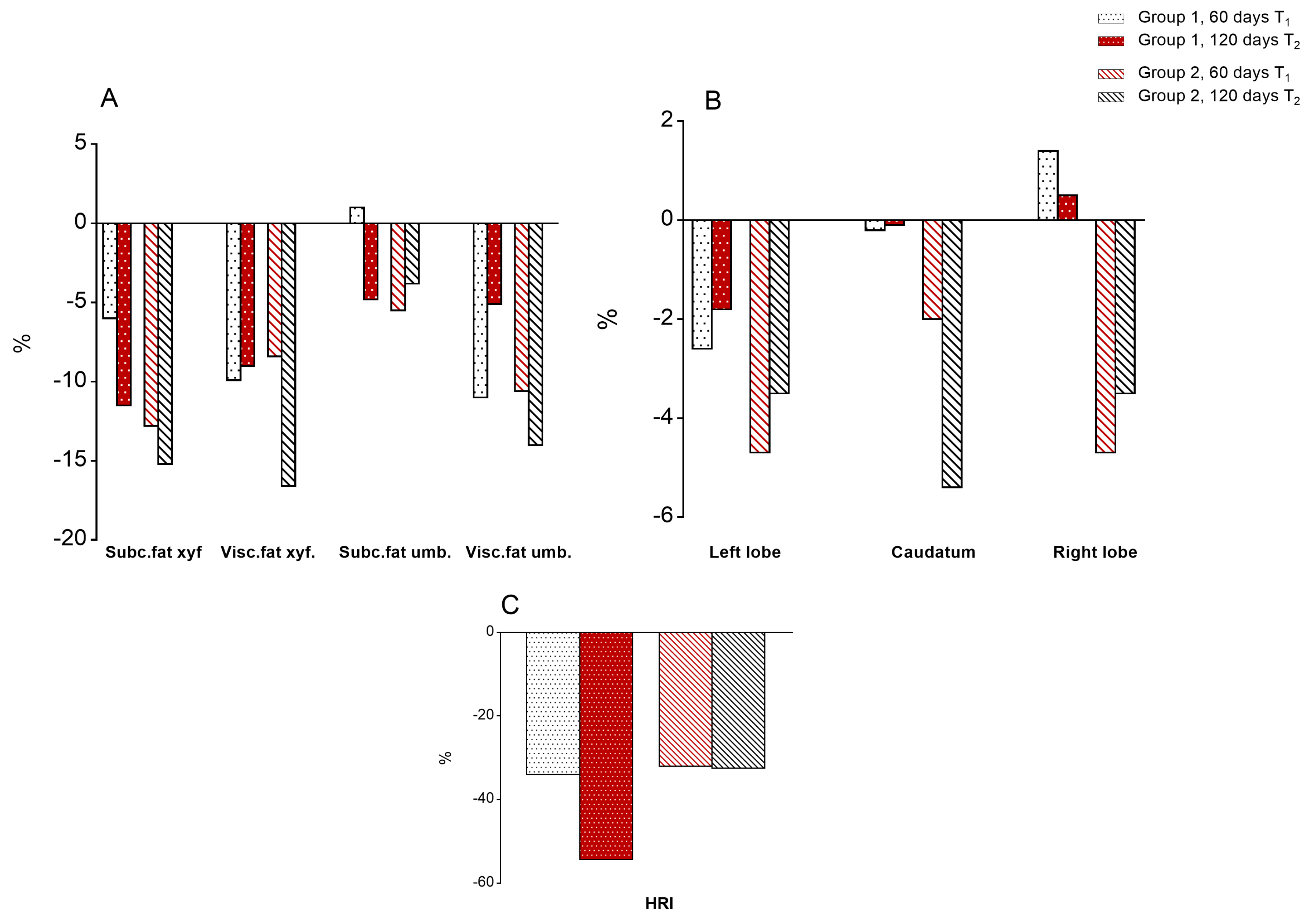

3.5.1. Body Fat

3.5.2. Liver Size

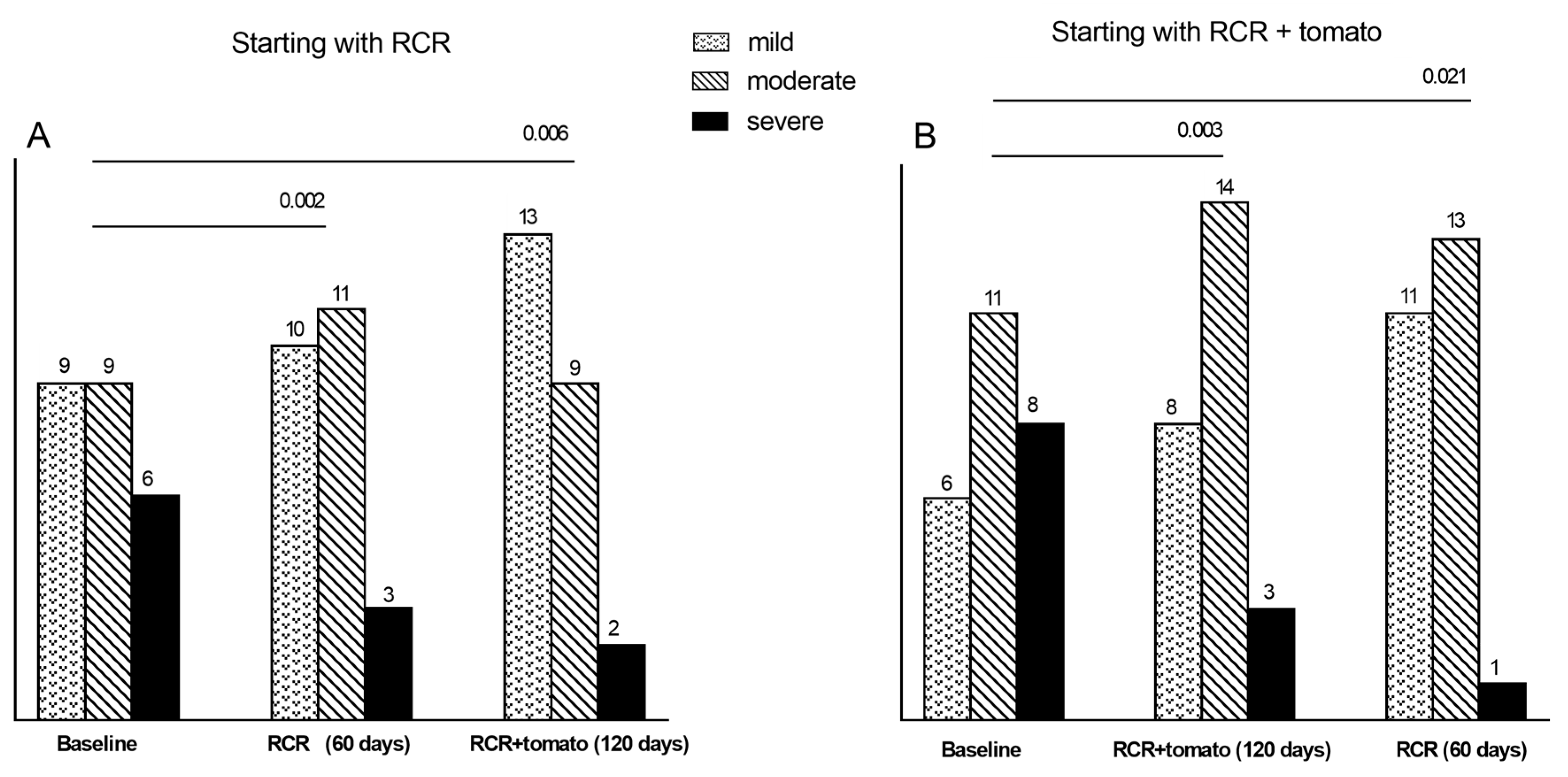

3.5.3. Degrees of Steatosis

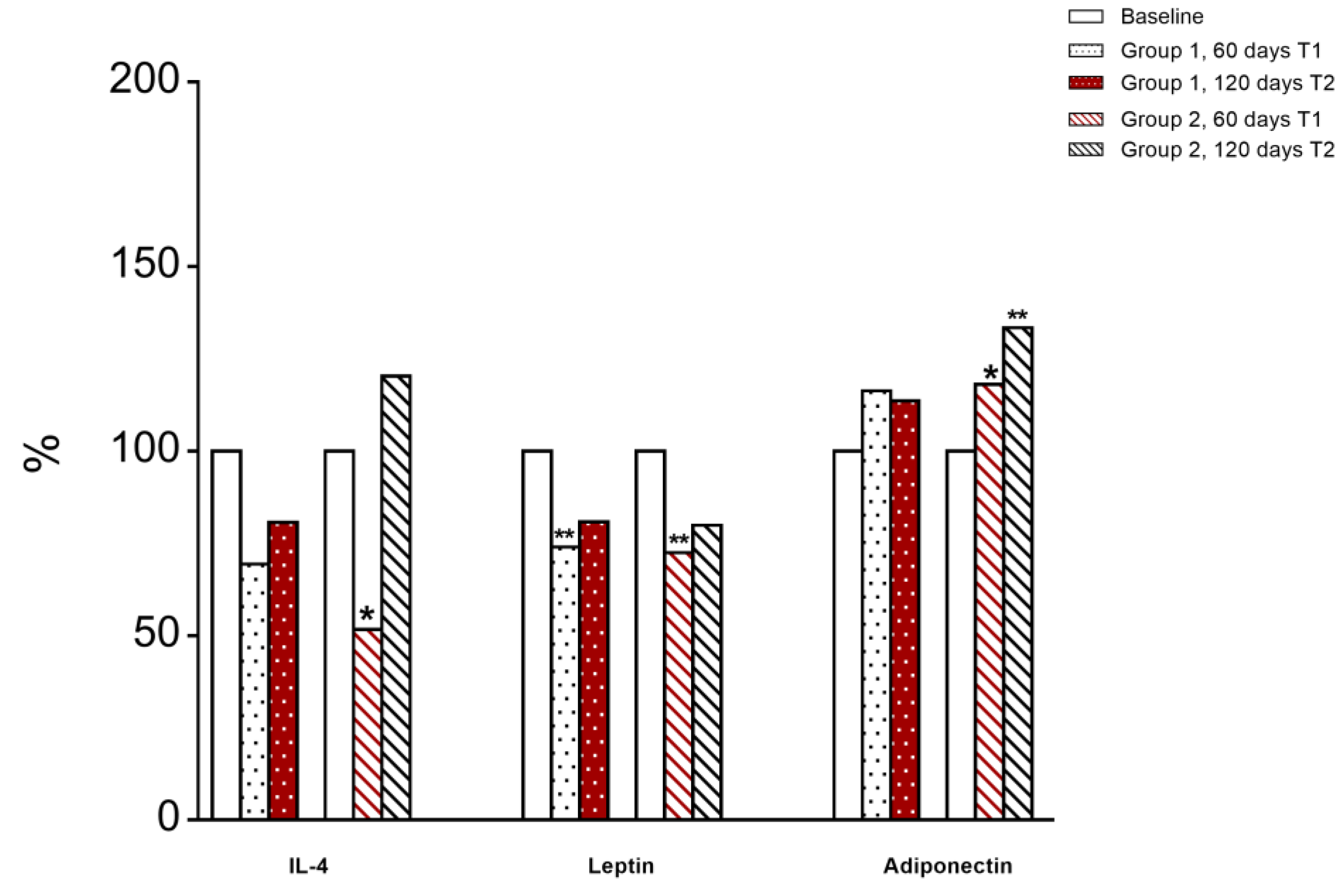

3.6. Immunological and Inflammatory Profile

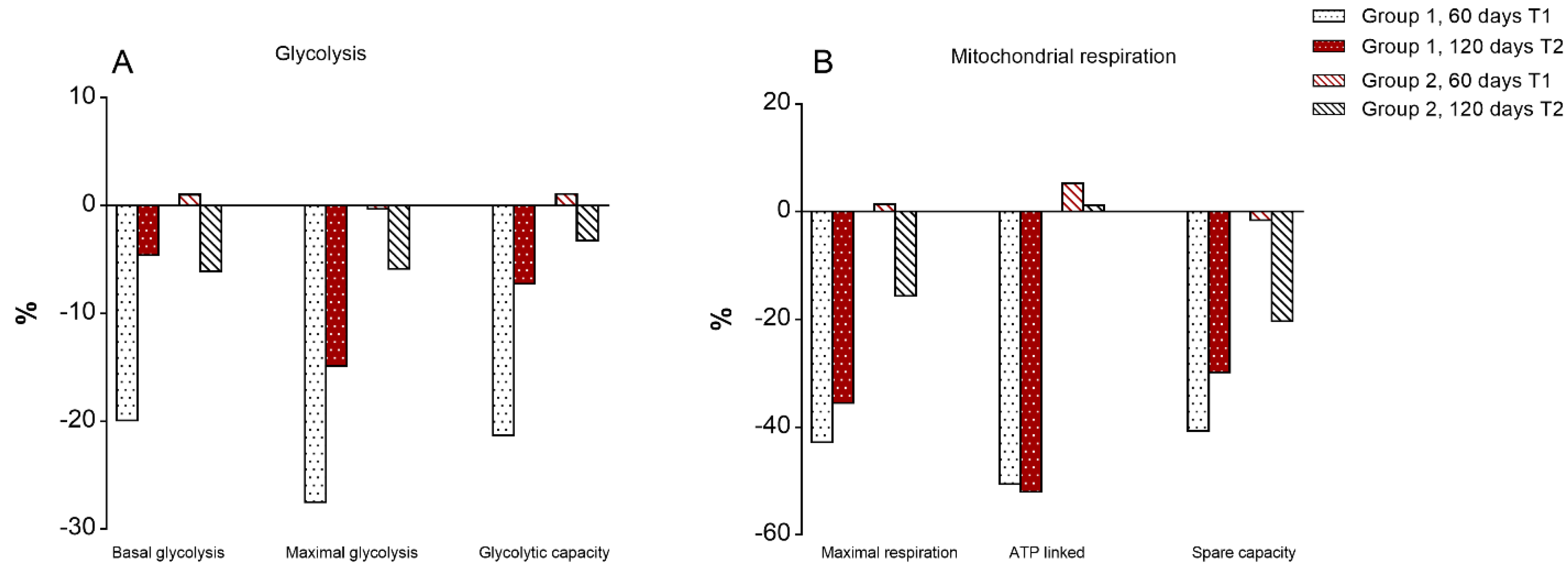

3.7. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T Lymphocytes

3.8. Multivariate Analysis of Differences between T1 and T0

4. Discussion

5. Study Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mollica, M.P.; Trinchese, G.; Cavaliere, G.; De Filippo, C.; Cocca, E.; Gaita, M.; Della Gatta, A.; Marano, A.; Mazzarella, G.; Bergamo, P. c9,t11-Conjugated linoleic acid ameliorates steatosis by modulating mitochondrial uncoupling and Nrf2 pathway. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, M.P.; Lionetti, L.; Putti, R.; Cavaliere, G.; Gaita, M.; Barletta, A. From chronic overfeeding to hepatic injury: Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amor, A.J.; Pinyol, M.; Solà, E.; Catalan, M.; Cofán, M.; Herreras, Z.; Amigó, N.; Gilabert, R.; Sala-Vila, A.; Ros, E.; et al. Relationship between noninvasive scores of Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nuclear magnetic resonance lipoprotein abnormalities: A focus on atherogenic dyslipidemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2017, 11, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, A.M.; Day, C. Cause, Pathogenesis, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Trenell, M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, G.; Spagnuolo, M.I.; Iorio, R. Obese children with fatty liver: Between reality and disease mongering. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 8277–8282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa, J.A.; Newton, K.P.; Schwimmer, J.B. Lifestyle interventions including Nutrition, Exercise and Supplements for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in children. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIver, N.J.; Michalek, R.D.; Rathmell, J.C. Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.L.; Poffenberger, M.C.; Chang, C.H.; Jones, R.G. Fueling immunity: Insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science 2013, 342, 1242454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procaccini, C.; Galgani, M.; De Rosa, V.; Carbone, F.; La Rocca, C.; Ranucci, G.; Iorio, R.; Matarese, G. Leptin: The prototypic adipocytokine and its role in NAFLD. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, C.; Mosca, A.; Vania, A.; Alterio, A.; Iasevoli, S.; Nobili, V. Good adherence to the Mediterranean diet reduces the risk for NASH and diabetes in pediatric patients with obesity: The results of an Italian Study. Nutrition 2017, 39, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Pozuelo, G.; Navarro-González, I.; González-Barrio, R.; Santaella, M.; García-Alonso, J.; Hidalgo, N.; Gómez-Gallego, C.; Ros, G.; Periago, M.J. The effect of Tomato juice supplementation on biomarkers and gene expression related to lipid metabolism in rats with induced hepatic steatosis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palozza, P.; Catalano, A.; Simone, R.; Cittadini, A. Lycopene as a guardian of redox signalling. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2012, 59, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.D. Lycopene metabolism and its biological significance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1214S–1222S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahcecioglu, I.H.; Kuzu, N.; Metin, K.; Ozercan, I.H.; Ustündag, B.; Sahin, K.; Kucuk, O. Lycopene prevents development of steatohepatitis in experimental nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model induced by high-fat diet. Vet. Med. Int. 2010, 262179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, A.; Stahl, W.; Sies, H.; Lirussi, F.; Donner, A.; Häussinger, D. Plasma levels of vitamin E and carotenoids are decreased in patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Eur. J. Med. Res. 2011, 16, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavipour, M.; Sotoudeh, G.; Ghorbani, M. Tomato juice consumption improves blood antioxidative biomarkers in overweight and obese females. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrovánková, S.; Mišurcová, L.; Machů, L. Antioxidant activity and protecting health effects of common medicinal plants. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 67, 75–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, M.S.; Yang, F.L.; Wang-Hsu, G.S.; Chen, B.H. Determination of major carotenoids in human serum by liquid chromatography. J. Food Drug Anal. 2004, 12, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L.; Garland, D.; Oliver, C.N.; Amici, A.; Climent, I.; Lenz, A.G.; Ahn, B.W.; Shaltiel, S.; Stadtman, E.R. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullane, K.M.; Westlin, W.; Kraemer, R. Activated neutrophils release mediators that may contribute to myocardial injury and dysfunction associated with ischemia and reperfusion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 524, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrieri, P.B.; Carbone, F.; Perna, F.; Bruzzese, D.; La Rocca, C.; Galgani, M.; Montella, S.; Petracca, M.; Florio, C.; Maniscalco, G.T.; et al. Longitudinal assessment of immuno-metabolic parameters in multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate. Metabolism. 2015, 64, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramon-Krauel, M.; Salsberg, S.L.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Voss, S.D.; Mulkern, R.V.; Apura, M.M.; Cooke, E.A.; Sarao, K.; Jonas, M.M.; Ludwig, D.S. A low-glycemic-load versus low-fat diet in the treatment of fatty liver in obese children. Child. Obes. 2013, 9, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Jaramillo, P.; Gómez-Arbeláez, D.; López-López, J.; López-López, C.; Martínez-Ortega, J.; Gómez-Rodríguez, A.; Triana-Cubillos, S. The role of leptin/adiponectin ratio in metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2014, 18, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galic, S.; Oakhill, J.S.; Steinberg, G.R. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 316, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fronzo, R.A.; Ferrannini, E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care 1991, 14, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Aronis, K.N.; Kountouras, J.; Raptis, D.D.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Mantzoros, C.S. Circulating leptin in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; La Rocca, C.; De Candia, P.; Procaccini, C.; Colamatteo, A.; Micillo, T.; De Rosa, V.; Matarese, G. Metabolic control of immune tolerance in health and autoimmunity. Semin. Immunol. 2016, 5, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyer, C.; Funahashi, T.; Tanaka, S.; Hotta, K.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Pratley, R.E.; Tataranni, P.A. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: Close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 1930–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiger, H.; Tschritter, O.; Machann, J.; Thamer, C.; Fritsche, A.; Maerker, E.; Schick, F.; Häring, H.U.; Stumvoll, M. Relationship of serum adiponectin and leptin concentrations with body fat distribution in humans. Obes. Res. 2003, 11, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Chang, Y.Y.; Huang, H.C.; Wu, Y.C.; Yang, M.D.; Chao, P.M. Tomato juice supplementation in young women reduces inflammatory adipokine levels independently of body fat reduction. Nutrition 2015, 31, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luvizotto, R.A.; Nascimento, A.F.; Miranda, N.C.; Wang, X.D.; Ferreira, A.L. Lycopene rich Tomato oleoresin modulates plasma adiponectin concentration and mRNA levels of adiponectin, SIRT1, and FoxO1 in adipose tissue of obese rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2015, 34, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenni, S.; Hammou, H.; Astier, J.; Bonnet, L.; Karkeni, E.; Couturier, C.; Tourniaire, F.; Landrier, J.F. Lycopene and Tomato powder supplementation similarly inhibit high-fat diet induced obesity, inflammatory response, and associated metabolic disorders. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1601083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mito, N.; Hosoda, T.; Kato, C.; Sato, K. Change of cytokine balance in diet-induced obese mice. Metabolism 2000, 49, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafi, M.; Yadav, P.; Reyes, M. Lycopene inhibits LPS-induced pro-inflammatory mediator inducible nitric oxide synthase in mouse macrophage cells. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, S069–S074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Seo, J.; Kim, H. Beta-Carotene and lutein inhibit hydrogen peroxide- induced activation of NF-kappaB and IL-8 expression in gastric epithelial AGS cells. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2010, 57, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouranton, E.; Thabuis, C.; Riollet, C.; Malezet-Desmoulins, C.; El Yazidi, C.; Amiot, M.J.; Borel, P.; Landrier, J.F. Lycopene inhibits proinflammatory cytokine and Chemokine expression in adipose tissue. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Sancho, A.M.; Gallego-Andujar, D.; Ruiz-Ocaña, P.; Visiedo, F.M.; Saez-Benito, A.; Schwarz, M.; Segundo, C.; Mateos, R.M. Obesity induced alterations in redox homeostasis and oxidative stress are present from an early age. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arauz, J.; Ramos-Tovar, E.; Muriel, P. Redox state and methods to evaluate oxidative stress in liver damage: From bench to bedside. Ann. Hepatol. 2016, 15, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Sinha, I.; Calcagnotto, A.; Trushin, N.; Haley, J.S.; Schell, T.D.; Richie, J.P., Jr. Oral supplementation with liposomal glutathione elevates body stores of glutathione and markers of immune function. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouranton, E.; Thabuis, C.; Riollet, C.; Malezet-Desmoulins, C.; El Yazidi, C.; Amiot, M.J.; Borel, P.; Landrier, J.F. Influence of lycopene and vitamin C from Tomato juice on biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Imrhan, V. Tomato esversus lycopene in oxidative stress and carcinogenesis: Conclusions from clinical trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konjar, Š.; Veldhoen, M. Dynamic Metabolic State of Tissue Resident CD8 T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimeloe, S.; Burgener, A.V.; Grählert, J.; Hess, C. T-cell metabolism governing activation, proliferation and differentiation; a modular view. Immunology 2017, 150, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, N.A.; Fontana, L.; Tosti, V.; Nikolich-Žugich, J. Calorie restriction induces reversible lymphopenia and lymphoid organ atrophy due to cell redistribution. Geroscience 2018, 40, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristan, D.M. Chronic calorie restriction increases susceptibility of laboratory mice (Mus musculus) to a primary intestinal parasite infection. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Differences between Values at 60 Days Versus Baseline | Wilks Lambda * | Exact F P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D-WAIST | 0.668 | 10.415 | 0.004 |

| 2 | D-MDA | 0.496 | 10.146 | 0.001 |

| 3 | D-Mitochondrial OCR | 0.467 | 7.238 | 0.002 |

| 4 | D-WEIGHT | 0.434 | 5.873 | 0.003 |

| 5 | D-ALT | 0.400 | 5.099 | 0.005 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negri, R.; Trinchese, G.; Carbone, F.; Caprio, M.G.; Stanzione, G.; di Scala, C.; Micillo, T.; Perna, F.; Tarotto, L.; Gelzo, M.; et al. Randomised Clinical Trial: Calorie Restriction Regimen with Tomato Juice Supplementation Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Preserves a Proper Immune Surveillance Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T-Lymphocytes in Obese Children Affected by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010141

Negri R, Trinchese G, Carbone F, Caprio MG, Stanzione G, di Scala C, Micillo T, Perna F, Tarotto L, Gelzo M, et al. Randomised Clinical Trial: Calorie Restriction Regimen with Tomato Juice Supplementation Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Preserves a Proper Immune Surveillance Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T-Lymphocytes in Obese Children Affected by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(1):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010141

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegri, Rossella, Giovanna Trinchese, Fortunata Carbone, Maria Grazia Caprio, Giovanna Stanzione, Carmen di Scala, Teresa Micillo, Francesco Perna, Luca Tarotto, Monica Gelzo, and et al. 2020. "Randomised Clinical Trial: Calorie Restriction Regimen with Tomato Juice Supplementation Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Preserves a Proper Immune Surveillance Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T-Lymphocytes in Obese Children Affected by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 1: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010141

APA StyleNegri, R., Trinchese, G., Carbone, F., Caprio, M. G., Stanzione, G., di Scala, C., Micillo, T., Perna, F., Tarotto, L., Gelzo, M., Cavaliere, G., Spagnuolo, M. I., Corso, G., Mattace Raso, G., Matarese, G., Mollica, M. P., Greco, L., & Iorio, R. (2020). Randomised Clinical Trial: Calorie Restriction Regimen with Tomato Juice Supplementation Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Preserves a Proper Immune Surveillance Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T-Lymphocytes in Obese Children Affected by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010141