Secretory Acid Sphingomyelinase in the Serum of Medicated Patients Predicts the Prospective Course of Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Description

2.2. Psychometric Scales

2.3. Blood Analysis

2.4. Determination of S-ASM Activity

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

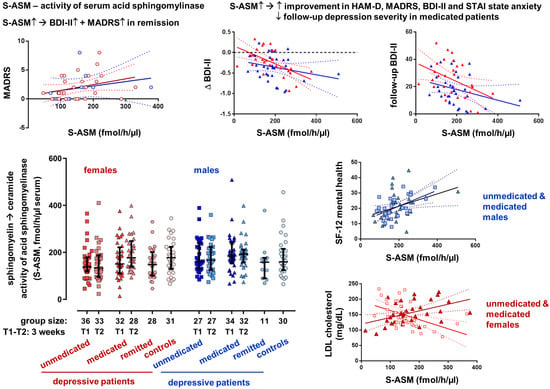

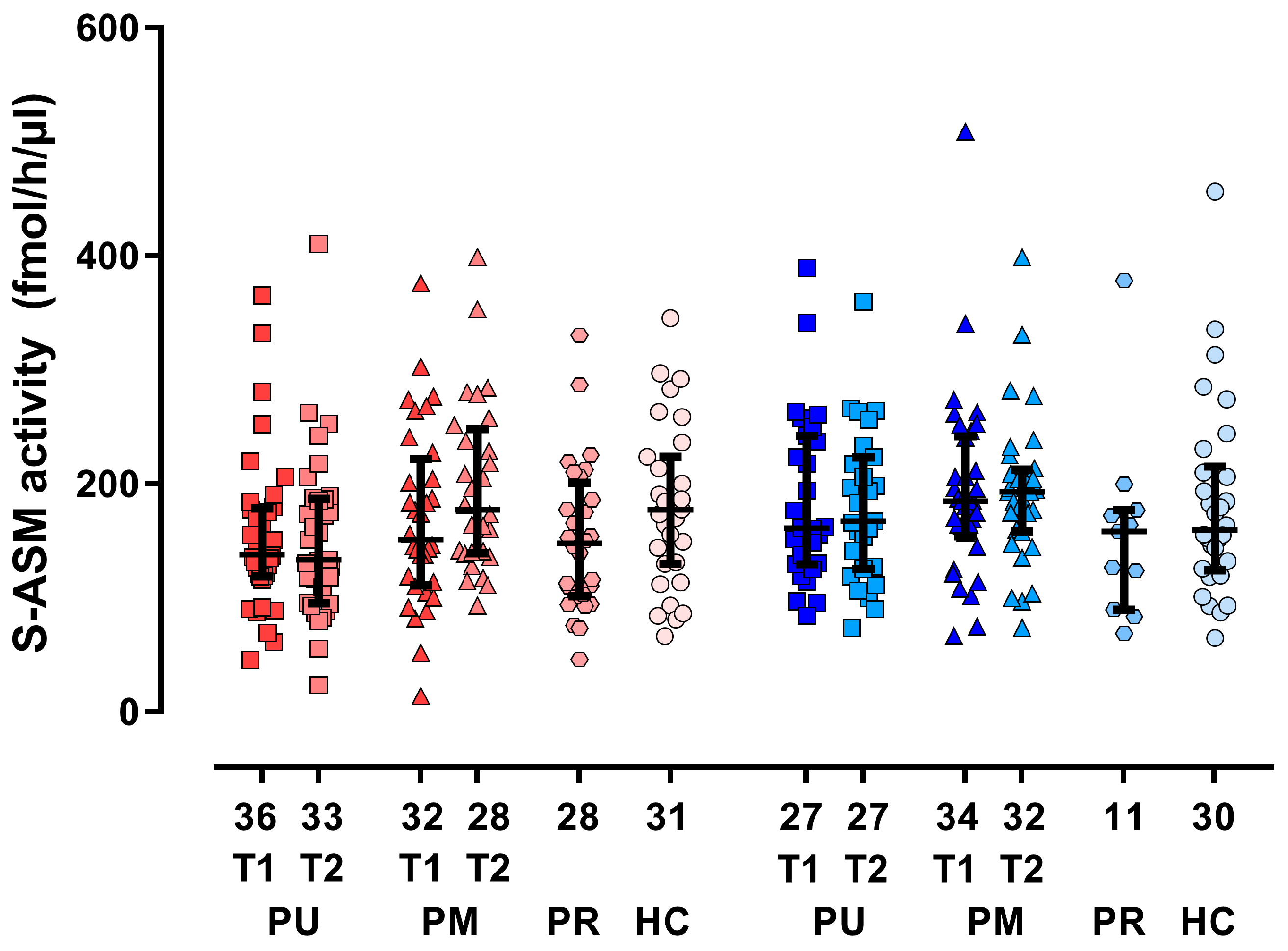

3.2. Group Differences and Time Course for S-ASM Activity

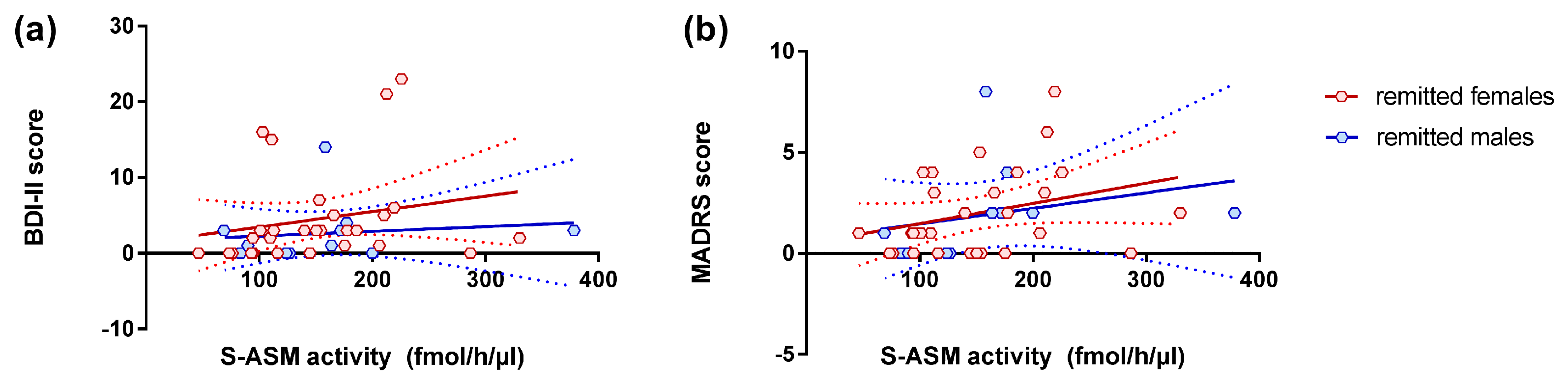

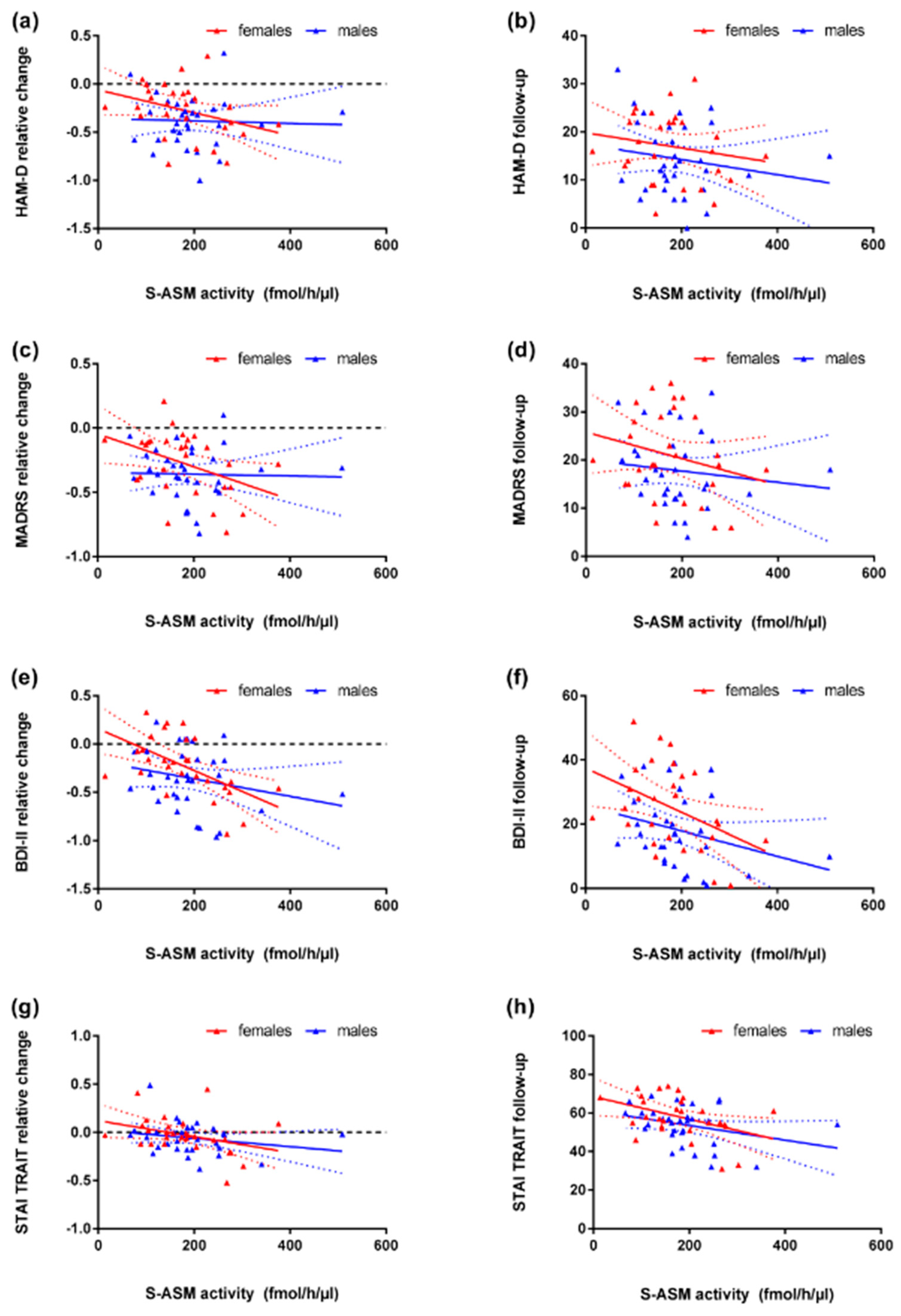

3.3. S-ASM Activity, Depression Severity, and Prospective Course

3.4. S-ASM Activity and State and Trait Anxiety (STAI)

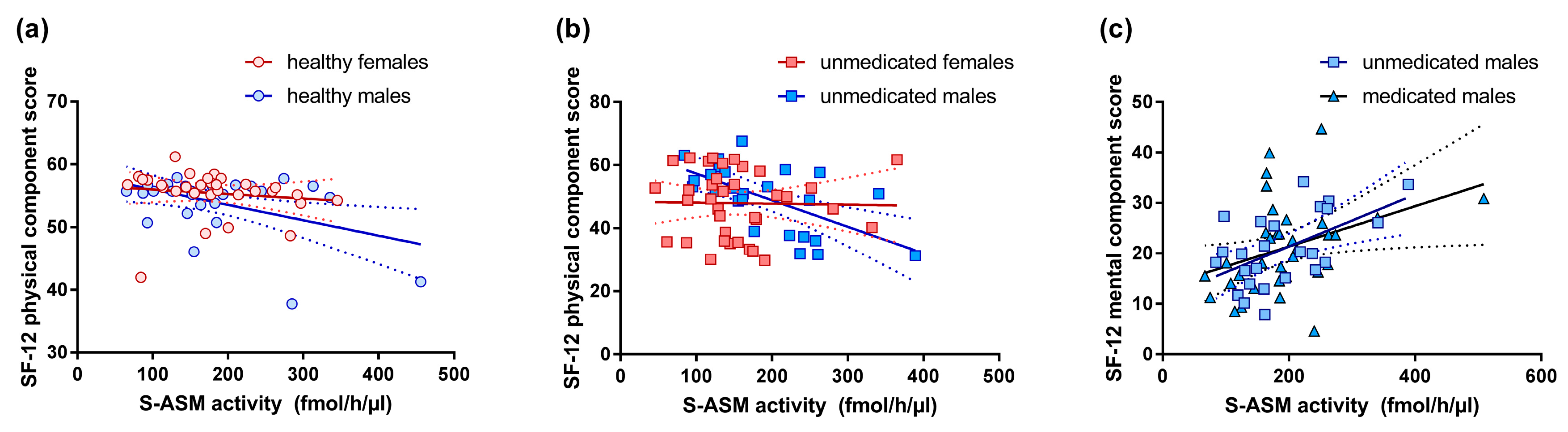

3.5. S-ASM Activity and Self-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life (SF-12)

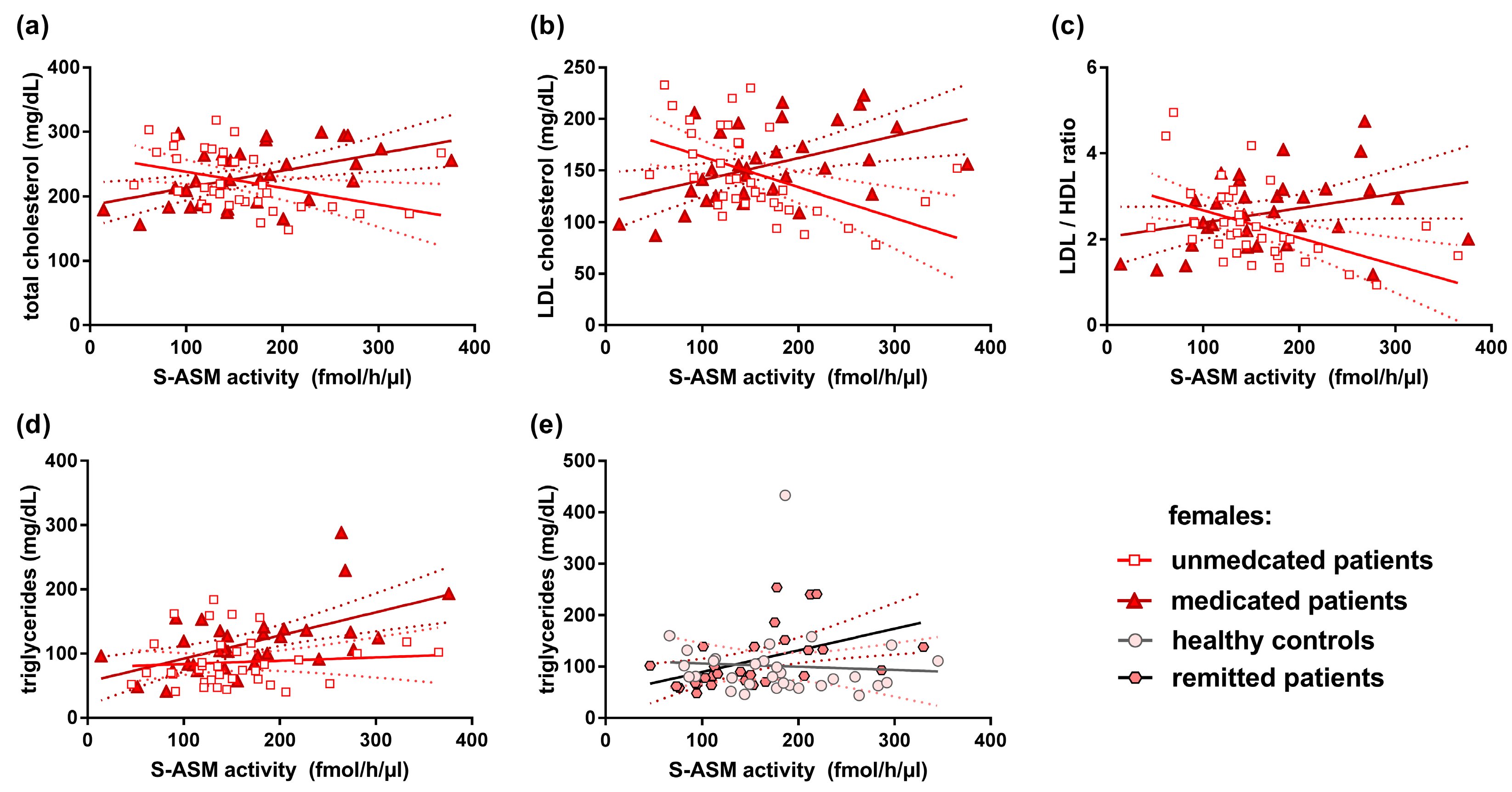

3.6. S-ASM Activity and Serum Lipid Levels

3.7. Replication of S-ASM Correlation with Liver Enzyme Activities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase (glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, GPT) |

| ASM | Acid sphingomyelinase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase (glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, GOT) |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory-II |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| FIASMA | Functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| L-ASM | Lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MDE | Major depressive episode |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| S-ASM | Secretory acid sphingomyelinase |

| SF-12 | Self-reported health-related quality of life |

| SMPD1 | Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1 gene encoding ASM |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

References

- Cuijpers, P.; Smit, F. Excess mortality in depression: A meta-analysis of community studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 72, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, R.L.; Bartelds, A.I.; Kerkhof, A.J.; Schellevis, F.G.; van der Zee, J. The epidemiology of suicide and attempted suicide in Dutch General Practice 1983–2003. BMC Fam. Pract. 2005, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, B.; Röther, M.; Bouna-Pyrrou, P.; Mühle, C.; Tektas, O.Y.; Kornhuber, J. The androgen model of suicide completion. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 172, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, B.; Thiem, D.; Bouna-Pyrrou, P.; Mühle, C.; Stoessel, C.; Betz, P.; Kornhuber, J. Low digit ratio (2D:4D) in male suicide victims. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 2016, 123, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chisholm, D.; Sanderson, K.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Saxena, S. Reducing the global burden of depression: Population-level analysis of intervention cost-effectiveness in 14 world regions. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 184, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, F.; Villa, R.F. The neurobiology of depression: An integrated overview from biological theories to clinical evidence. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 4847–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, G.; Sperling, W.; Richter-Schmidinger, T.; Mühle, C.; Heberlein, A.; Maihofner, C.; Kornhuber, J.; Lenz, B. Serial repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) decreases BDNF serum levels in healthy male volunteers. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 2014, 121, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühle, C.; Reichel, M.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Sphingolipids in psychiatric disorders and pain syndromes. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2013, 431–456. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meer, G.; Voelker, D.R.; Feigenson, G.W. Membrane lipids: Where they are and how they behave. Nature reviews. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 9, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, N.C.; Oskeritzian, C.A.; Paugh, S.W.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. Sphingosine kinases, sphingosine 1-phosphate, apoptosis and diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1758, 2016–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nature reviews. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018, 19, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelik, A.; Illes, K.; Heinz, L.X.; Superti-Furga, G.; Nagar, B. Crystal structure of mammalian acid sphingomyelinase. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, R.W.; Canals, D.; Hannun, Y.A. Roles and regulation of secretory and lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase. Cell. Signal. 2009, 21, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchman, E.H. Acid sphingomyelinase, cell membranes and human disease: Lessons from Niemann-Pick disease. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1895–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornhuber, J.; Rhein, C.; Müller, C.P.; Mühle, C. Secretory sphingomyelinase in health and disease. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 707–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornhuber, J.; Medlin, A.; Bleich, S.; Jendrossek, V.; Henkel, A.W.; Wiltfang, J.; Gulbins, E. High activity of acid sphingomyelinase in major depression. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 2005, 112, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albouz, S.; Le Saux, F.; Wenger, D.; Hauw, J.J.; Baumann, N. Modifications of sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine metabolism by tricyclic antidepressants and phenothiazines. Life Sci. 1986, 38, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhuber, J.; Tripal, P.; Reichel, M.; Mühle, C.; Rhein, C.; Muehlbacher, M.; Groemer, T.W.; Gulbins, E. Functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase (FIASMAs): A novel pharmacological group of drugs with broad clinical applications. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 26, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbins, E.; Palmada, M.; Reichel, M.; Luth, A.; Bohmer, C.; Amato, D.; Muller, C.P.; Tischbirek, C.H.; Groemer, T.W.; Tabatabai, G.; et al. Acid sphingomyelinase-ceramide system mediates effects of antidepressant drugs. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhuber, J.; Reichel, M.; Tripal, P.; Groemer, T.W.; Henkel, A.W.; Mühle, C.; Gulbins, E. The role of ceramide in major depressive disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 259 (Suppl. 2), S199–S204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Garcia, P.; Rao, V.; Haughey, N.J.; Bandaru, V.V.; Smith, G.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Lobo, A.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Mielke, M.M. Elevated plasma ceramides in depression. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirkan, A.; Isaacs, A.; Ugocsai, P.; Liebisch, G.; Struchalin, M.; Rudan, I.; Wilson, J.F.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Gyllensten, U.; Campbell, H.; et al. Plasma phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin concentrations are associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in a Dutch family-based lipidomics study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, S.M.; Truman, J.P.; Al Gadban, M.M.; Smith, K.J.; Twal, W.O.; Hamner, M.B. Altered blood sphingolipidomics and elevated plasma inflammatory cytokines in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurobiol. Lipids 2012, 10, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, T.G.; Chan, R.B.; Bravo, F.V.; Miranda, A.; Silva, R.R.; Zhou, B.; Marques, F.; Pinto, V.; Cerqueira, J.J.; Di Paolo, G.; et al. The impact of chronic stress on the rat brain lipidome. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichel, M.; Rhein, C.; Hofmann, L.M.; Monti, J.; Japtok, L.; Langgartner, D.; Fuchsl, A.M.; Kleuser, B.; Gulbins, E.; Hellerbrand, C.; et al. Chronic psychosocial stress in mice is associated with increased acid sphingomyelinase activity in liver and serum and with hepatic C16:0-ceramide accumulation. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huston, J.P.; Kornhuber, J.; Mühle, C.; Japtok, L.; Komorowski, M.; Mattern, C.; Reichel, M.; Gulbins, E.; Kleuser, B.; Topic, B.; et al. A sphingolipid mechanism for behavioral extinction. J. Neurochem. 2016, 137, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichel, M.; Greiner, E.; Richter-Schmidinger, T.; Yedibela, O.; Tripal, P.; Jacobi, A.; Bleich, S.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Increased acid sphingomyelinase activity in peripheral blood cells of acutely intoxicated patients with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichel, M.; Beck, J.; Mühle, C.; Rotter, A.; Bleich, S.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Activity of secretory sphingomyelinase is increased in plasma of alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühle, C.; Amova, V.; Biermann, T.; Bayerlein, K.; Richter-Schmidinger, T.; Kraus, T.; Reichel, M.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Sex-dependent decrease of sphingomyelinase activity during alcohol withdrawal treatment. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 34, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühle, C.; Weinland, C.; Gulbins, E.; Lenz, B.; Kornhuber, J. Peripheral acid sphingomyelinase activity is associated with biomarkers and phenotypes of alcohol use and dependence in patients and healthy controls. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.P.; Kalinichenko, L.S.; Tiesel, J.; Witt, M.; Stöckl, T.; Sprenger, E.; Fuchser, J.; Beckmann, J.; Praetner, M.; Huber, S.E.; et al. Paradoxical antidepressant effects of alcohol are related to acid sphingomyelinase and its control of sphingolipid homeostasis. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, C.J.; Musenbichler, C.; Böhm, L.; Färber, K.; Fischer, A.I.; von Nippold, F.; Winkelmann, M.; Richter-Schmidinger, T.; Mühle, C.; Kornhuber, J.; et al. LDL cholesterol relates to depression, its severity, and the prospective course. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 92, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Laux, L.; Glanzmann, P.; Schaffner, P.; Spielberger, C.D. STAI. Das Stait-Trait-Angstinventar; Beltz Test Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger, M.; Kirchberger, I. Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Handanweisung; Hogrefe-Verlag: München, Göttingen, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mühle, C.; Kornhuber, J. Assay to measure sphingomyelinase and ceramidase activities efficiently and safely. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1481, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, R. What do we know about sex differences in depression: A review of animal models and potential mechanisms. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 89, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seney, M.L.; Huo, Z.; Cahill, K.; French, L.; Puralewski, R.; Zhang, J.; Logan, R.W.; Tseng, G.; Lewis, D.A.; Sibille, E. Opposite molecular signatures of depression in men and women. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, L.J. Measures of anxiety: State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. 11), S467–S472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunkhorst-Kanaan, N.; Klatt-Schreiner, K.; Hackel, J.; Schröter, K.; Trautmann, S.; Hahnefeld, L.; Wicker, S.; Reif, A.; Thomas, D.; Geisslinger, G.; et al. Targeted lipidomics reveal derangement of ceramides in major depression and bipolar disorder. Metabolism 2019, 95, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, C.L.; Nagle, M.W.; Tian, C.; Chen, X.; Paciga, S.A.; Wendland, J.R.; Tung, J.Y.; Hinds, D.A.; Perlis, R.H.; Winslow, A.R. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas Boas, G.R.; Boerngen de Lacerda, R.; Paes, M.M.; Gubert, P.; Almeida, W.; Rescia, V.C.; de Carvalho, P.M.G.; de Carvalho, A.A.V.; Oesterreich, S.A. Molecular aspects of depression: A review from neurobiology to treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 851, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yugi, K.; Kubota, H.; Hatano, A.; Kuroda, S. Trans-omics: How to reconstruct biochemical networks across multiple ‘omic’ layers. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.A.; Campbell, L.A.; Lehman, C.L.; Grisham, J.R.; Mancill, R.B. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the dsm-iv anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttila, V.; Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Finucane, H.K.; Walters, R.K.; Bras, J.; Duncan, L.; Escott-Price, V.; Falcone, G.J.; Gormley, P.; Malik, R.; et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science 2018, 360, eaap8757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kendler, K.S. Major depression and generalised anxiety disorder. Same genes, (partly) different environments—Revisited. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl. 1996, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, K.; Lueken, U.; Muehlhan, M.; Beesdo-Baum, K. Separating generalized anxiety disorder from major depression using clinical, hormonal, and structural MRI data: A multimodal machine learning study. Brain Behav. 2017, 7, e00633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoicas, I.; Reichel, M.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Role of acid sphingomyelinase in the regulation of social behavior and memory. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Yu, J.; Shi, R.; Yan, L.; Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Bai, Y.; Schuchman, E.H.; et al. Elevation of ceramide and activation of secretory acid sphingomyelinase in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Coron. Artery Dis. 2014, 25, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambire, K.F.; Fernandez-Mosquera, L.; Steinfeld, R.; Mühle, C.; Ikonen, E.; Milosevic, I.; Raimundo, N. Mitochondrial biogenesis is transcriptionally repressed in lysosomal lipid storage diseases. eLife 2019, 8, e39598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, M.; Chida, Y. Life satisfaction and inflammatory biomarkers: The 2008 Scottish health survey. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2011, 53, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faugere, M.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.A.; Faget-Agius, C.; Lancon, C.; Cermolacce, M.; Richieri, R. Quality of life is associated with chronic inflammation in depression: A cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Guo, Y.; Shenkman, E.; Muller, K. Assessing the reliability of the short form 12 (SF-12) health survey in adults with mental health conditions: A report from the wellness incentive and navigation (WIN) study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, C.; Tripal, P.; Seebahn, A.; Konrad, A.; Kramer, M.; Nagel, C.; Kemper, J.; Bode, J.; Mühle, C.; Gulbins, E.; et al. Functional implications of novel human acid sphingomyelinase splice variants. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, C.; Reichel, M.; Kramer, M.; Rotter, A.; Lenz, B.; Mühle, C.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Alternative splicing of SMPD1 coding for acid sphingomyelinase in major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 209, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühle, C.; Huttner, H.B.; Walter, S.; Reichel, M.; Canneva, F.; Lewczuk, P.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Characterization of acid sphingomyelinase activity in human cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | PU | PM | PR | HC | p Values for Group Difference | p Values for Sex Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU vs. PM | PU vs. HC | PM vs. HC | PR vs. HC | PU | PM | PR | HC | |||||

| n (females/males) at inclusion | 36/27 | 32/34 | 28/11 | 31/30 | 0.325 | 0.480 | 0.793 | 0.038 | ||||

| n (females/males) at follow-up | 341/272 | 28/32 | -/- | -/- | 0.318 | |||||||

| age (years) | 47 (34–53) | 46 (33–54) | 49 (46–58) | 42 (32–54) | 0.908 | 0.455 | 0.609 | 0.019 | 0.692 | 0.603 | 0.132 | 0.168 |

| total education years a | 15 (13–18) | 14 (13–16) | 14 (13–16) | 15 (13–18) | 0.062 | 0.933 | 0.080 | 0.221 | 0.172 | 0.354 | 0.225 | 0.087 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 25.3 (22.5–27.8) | 28.5 (24.4–30.4) | 25.7 (23.0–29.1) | 24.4 (23–27.7) | <0.001 | 0.760 | 0.001 | 0.281 | 0.090 | 0.182 | 0.528 | 0.279 |

| BDI-II score at inclusion | 28 (22–34) | 29 (24–35) | 3 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | 0.432 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.280 | 0.416 | 0.020 | 0.414 | 0.683 |

| BDI-II score at follow-up c | 20 (15–25) | 20 (13–31) | 0.939 | 0.154 | 0.041 | |||||||

| BDI-II score at relative change c | −0.27 (−0.42–−0.12) | −0.32 (−0.51–−0.07) | 0.508 | 0.161 | 0.134 | |||||||

| HAM-D score at inclusion | 21 (19–24) | 23 (20–26) | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0.064 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.818 | 0.151 | 0.678 | 0.050 |

| HAMD-D score at follow-up c | 18 (14–21) | 15 (10–22) | 0.189 | 0.529 | 0.150 | |||||||

| HAMD-D score at relative change c | −0.15 (−0.38–−0.05) | −0.32 (−0.51–−0.16) | 0.010 | 0.788 | 0.083 | |||||||

| MADRS score at inclusion | 26 (23–28) | 28 (24– 34) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | 0.057 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.460 | 0.322 | 0.818 | 0.069 |

| MADRS score at follow-up c | 21 (18–25) | 18 (13–26) | 0.143 | 0.398 | 0.170 | |||||||

| MADRS score relative change c | −0.19 (−0.34–−0.07) | −0.32 (−0.46–−0.14) | 0.010 | 0.387 | 0.094 | |||||||

| STAI state score at inclusion | 50 (40–57) | 54 (43–63) | 32 (26–36) | 28 (26–31) | 0.080 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.036 | 0.160 | 0.142 | 0.158 | 0.238 |

| STAI state score at follow-up c | 46 (37–52) | 47 (42–57) | 0.261 | 0.210 | 0.157 | |||||||

| STAI state score relative change c | −0.06 (−0.15–0.02) | −0.05 (−0.14–0.09) | 0.583 | 0.754 | 0.917 | |||||||

| STAI trait score at inclusion | 62 (56–67) | 61 (52–67) | 33 (26–40) | 28 (25–33) | 0.261 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.486 | 0.261 | 0.116 | 0.448 |

| STAI trait score at follow-up c | 59 (54–63) | 56 (51–65) | 0.530 | 0.911 | 0.121 | |||||||

| STAI trait score relative change c | −0.06 (−0.12–0.01) | −0.04 (−0.14–0.03) | 0.558 | 0.703 | 0.142 | |||||||

| SF-12 physical component score b | 50.9 (38.7–57.6) | 50.9 (43.8–57.1) | 55.5 (50.1–56.5) | 55.7 (54.9–56.7) | 0.432 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.124 | 0.524 | 0.206 | 0.390 | 0.097 |

| SF-12 mental component score b | 19.9 (16.6–27.6) | 18.5 (14.3–26.6) | 53.2 (48.7–57.8) | 56.2 (52.1–58.9) | 0.165 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.240 | 0.486 | 0.501 | 0.140 | 0.351 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.9 (0.5–2.1) | 1.6 (1.1–3.1) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.005 | 0.139 | 0.127 | 0.373 | 0.813 | 0.913 | 0.221 | 0.129 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 90 (68–124) | 127 (97–174) | 93 (68–138) | 81 (63–142) | <0.001 | 0.944 | <0.001 | 0.445 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.939 | 0.665 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 217 (187–264) | 235 (198–267) | 227 (201–251) | 208 (181–248) | 0.256 | 0.313 | 0.028 | 0.198 | 0.868 | 0.719 | 0.083 | 0.226 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 59 (52–66) | 51 (43– 64) | 58 (46–68) | 58 (50–69) | 0.007 | 0.976 | 0.018 | 0.641 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 143 (118–179) | 159 (132–196) | 151 (139–167) | 134 (117–167) | 0.070 | 0.182 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.433 | 0.151 | 0.414 | 0.608 |

| HDL/LDL ratio | 2.4 (1.9–3.3) | 3 (2.3–4) | 2.6 (1.9–3.3) | 2.2 (1.8–3.0) | 0.003 | 0.270 | <0.001 | 0.158 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.037 | 0.055 |

| GGT (U/L) | 21 (15–30) | 25 (17–42) | 18 (13–32) | 19 (15–26) | 0.044 | 0.527 | 0.012 | 0.966 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.167 | 0.104 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19 (15–29) | 26 (17–41) | 18 (15–26) | 22 (16–31) | 0.043 | 0.444 | 0.209 | 0.210 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.040 | 0.002 |

| AST (U/L) | 23 (19–26) | 24 (21–32) | 24 (20–28) | 26 (22–30) | 0.118 | 0.005 | 0.250 | 0.072 | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.158 | 0.002 |

| S-ASM (fmol/h/µL serum) at inclusion | 151 (121–206) | 176 (125–228) | 150 (101–186) | 173 (130–214) | 0.166 | 0.237 | 0.828 | 0.068 | 0.080 | 0.191 | 0.939 | 0.863 |

| S-ASM (fmol/h/µL serum) at follow-up c | 160 (114–202) | 189 (143–227) | 0.013 | 0.076 | 0.917 | |||||||

| S-ASM relative change c | 0.03 (−0.19–0.22) | 0.10 (−0.08–0.28) | 0.200 | 0.994 | 0.273 | |||||||

| S-ASM Activity | HAM-D | MADRS | BDI-II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | |

| All | 39 | 0.143 | 0.386 | 0.451 | 0.004 | 0.385 | 0.015 |

| Female | 28 | 0.146 | 0.459 | 0.368 | 0.054 | 0.424 | 0.024 |

| Male | 11 | 0.155 | 0.648 | 0.667 | 0.025 | 0.259 | 0.442 |

| S-ASM Activity | Relative Change of Score from Inclusion to Follow-Up | Sum Score at Follow-Up | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D | MADRS | BDI-II | STAI (Trait) | HAM-D | MADRS | BDI-II | STAI (Trait) | |||||||||||

| n | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | ||

| Unmedicated | all | 60 | 0.231 | 0.075 | 0.066 | 0.618 | −0.112 | 0.396 | −0.149 | 0.256 | 0.082 | 0.534 | −0.054 | 0.682 | −0.007 | 0.956 | 0.044 | 0.736 |

| Patients | female | 34 | 0.136 | 0.443 | −0.024 | 0.895 | −0.148 | 0.403 | −0.127 | 0.476 | 0.021 | 0.904 | −0.100 | 0.575 | 0.059 | 0.741 | 0.265 | 0.129 |

| With current MDE | male | 26 | 0.295 | 0.144 | 0.236 | 0.245 | 0.069 | 0.736 | −0.119 | 0.563 | 0.213 | 0.295 | 0.100 | 0.628 | −0.123 | 0.551 | −0.269 | 0.184 |

| Medicated | all | 60 | −0.300 | 0.020 | −0.306 | 0.017 | −0.411 | 0.001 | −0.344 | 0.007 | -0.206 | 0.114 | −0.240 | 0.065 | −0.367 | 0.004 | −0.376 | 0.003 |

| Patients | female | 28 | −0.400 | 0.035 | −0.401 | 0.035 | −0.585 | 0.001 | −0.406 | 0.032 | -0.182 | 0.354 | −0.202 | 0.302 | −0.389 | 0.041 | −0.395 | 0.037 |

| With current MDE | male | 32 | −0.094 | 0.607 | −0.130 | 0.479 | −0.184 | 0.314 | −0.231 | 0.203 | -0.127 | 0.487 | −0.158 | 0.388 | −0.271 | 0.134 | −0.291 | 0.106 |

| S-ASM Activity | Triglycerides | Total Cholesterol | LDL Cholesterol | LDL/HDL Ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | |

| Unmedicated females | 36 | 0.103 | 0.549 | −0.531 | 0.0009 | −0.596 | 0.0001 | −0.571 | 0.0003 |

| Medicated females | 32 | 0.533 | 0.002 | 0.481 | 0.005 | 0.487 | 0.005 | 0.302 | 0.093 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mühle, C.; Wagner, C.J.; Färber, K.; Richter-Schmidinger, T.; Gulbins, E.; Lenz, B.; Kornhuber, J. Secretory Acid Sphingomyelinase in the Serum of Medicated Patients Predicts the Prospective Course of Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8060846

Mühle C, Wagner CJ, Färber K, Richter-Schmidinger T, Gulbins E, Lenz B, Kornhuber J. Secretory Acid Sphingomyelinase in the Serum of Medicated Patients Predicts the Prospective Course of Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(6):846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8060846

Chicago/Turabian StyleMühle, Christiane, Claudia Johanna Wagner, Katharina Färber, Tanja Richter-Schmidinger, Erich Gulbins, Bernd Lenz, and Johannes Kornhuber. 2019. "Secretory Acid Sphingomyelinase in the Serum of Medicated Patients Predicts the Prospective Course of Depression" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 6: 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8060846

APA StyleMühle, C., Wagner, C. J., Färber, K., Richter-Schmidinger, T., Gulbins, E., Lenz, B., & Kornhuber, J. (2019). Secretory Acid Sphingomyelinase in the Serum of Medicated Patients Predicts the Prospective Course of Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(6), 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8060846