Abstract

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a frequent and serious condition, potentially life-threatening and leading to lower-limb amputation. Its pathophysiology is generally related to ischemia-reperfusion cycles, secondary to reduction or interruption of the arterial blood flow followed by reperfusion episodes that are necessary but also—per se—deleterious. Skeletal muscles alterations significantly participate in PAD injuries, and interestingly, muscle mitochondrial dysfunctions have been demonstrated to be key events and to have a prognosis value. Decreased oxidative capacity due to mitochondrial respiratory chain impairment is associated with increased release of reactive oxygen species and reduction of calcium retention capacity leading thus to enhanced apoptosis. Therefore, targeting mitochondria might be a promising therapeutic approach in PAD.

1. Introduction

Peripheral arterial diseases (PAD) is a major concern for public healthcare, affecting more than 200 million individual worldwide [1,2]. Its prevalence varies from 3% to 10%, but can reach up to 20% in the elderly population [3].

PAD is defined by a narrowing of the peripheral arterial vasculature. It mostly affects lower limbs, leading to overall functional disability and reduced quality of life. Initially asymptomatic, PAD progressively compromises lower limb vascularization, leading to obstruction of the vessels by atheroma. PAD includes all stages of the disease, from asymptomatic with abolition of distal pulses, to intermittent claudication or critical limb threatening ischemia (CLTI) characterized by rest pain and/or ulcers. PAD is also often associated with cognitive dysfunction characterized by reduced performance in nonverbal reasoning, reduced verbal fluency, and decreased information processing speed [4]. Thus, PAD is a serious condition threatening both limb (risk of amputation) and vital prognosis of the patients. Indeed, despite recent therapeutic progress, morbidity and mortality rates remain incompressible around 20% and 15% five years after a diagnosis of symptomatic or asymptomatic PAD [5]. On average, the life expectancy of claudicating patients is reduced by 10 years, with a majority of death attributable to cardiovascular causes.

The treatment of PAD is mainly based on revascularization of the ischemic limb [6]. Nevertheless, this surgical procedure is not always possible, notably when the vascular state is too precarious or when the local evolution is too advanced. It appears therefore important to better understand PAD pathophysiology to offer optimal patient care. Indeed, insufficient oxygen supply was long presumed to be the main and sole cause for PAD symptoms. However, recent advances in understanding PAD physiopathology identified mitochondria as a key element in the deleterious process of PAD [7,8].

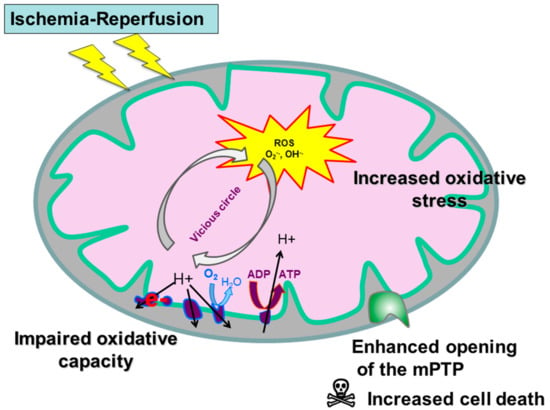

Thus, skeletal muscles alterations significantly participate in PAD injuries, modulating its prognosis, and this review aims to describe muscle mitochondrial dysfunctions. Particularly, we will analyze data focused on mitochondrial respiratory chain respiration, on reactive oxygen species release and on mitochondrial calcium retention capacity which decrease is associated with enhanced apoptosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial dysfunction during peripheral arterial disease (PAD). mPTP: mitochondrial permeability transition pore.

2. Mitochondrial Function under Normal and Pathological Conditions

2.1. Normal Condition

Life requires energy, and this energy is stored in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules, that are produced in the mitochondria by oxidative phosphorylation and assessed through mitochondrial respiration determination. Specifically, the oxidation of nutrients through the Krebs cycle provides reduced coenzymes (the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)) and to a lesser extent flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2), which are electron donors. This flow of electrons is supported by different redox reactions provided by the four complexes of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, up to the reduction of molecular oxygen in water. The respiratory complexes use the energy generated by this electron transfer to allow an active translocation of protons from the matrix to the inter-membrane mitochondrial space. This expulsion of protons results in the generation of a concentration gradient and a mitochondrial membrane potential across the inner membrane. ATP synthases use the transmembrane protonmotive force as a source of energy to drive a mechanical rotary mechanism leading to the chemical synthesis of ATP from ADP and Pi.The F1F0 ATP synthase enzymes allow proton flux and ATP synthesis through a and c subunits of the F0 domain. The maintenance of this electrochemical gradient, also called protomotive force, is an essential element for the energetic role of the mitochondria [9,10,11].

Mitochondrial respiration generates free radicals derived from oxygen, the reactive oxygen species (ROS). A free radical is a chemical species containing an unpaired electron. Extremely unstable, this compound can react with more stable molecules to match its electron. It can then pull out an electron and behave as an oxidant, usually leading to the formation of new radicals in the chain and causing significant cell damage. Main ROS comprise superoxide anion, the hydroxyl radical and the highly reactive compound hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Detoxification systems exist, enzymatic (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) or not (vitamins and trace elements).

Nevertheless, when the radical production remains contained below a certain threshold, the ROS activate defenses pathways involving the development of cellular antioxidants and mitochondrial biogenesis. Also named mitohormesis, these mechanisms constitute one of the therapeutic targets that can limit the lesions linked to repeated cycles of ischemia-reperfusion in PAD [12].

2.2. Ischemic Condition

During ischemia, ATP is generated by anaerobic glycolysis, leading to glycogen storage depletion, anaerobic metabolism activation and local lactic acidosis. The resulting depletion of ATP reduces the function of membrane pumps and causes cellular edema. Indeed, the cell tends to correct the acidosis by expelling the H+ ions via the Na+/H+ exchanger, thus saturating the cytoplasm with Na + ions and causing an osmotic shift to the cytoplasm. Cell edema is aggravated by Na+/K+ ATP-dependent exchanger dysfunction due to lack of ATP, which also leads to Na+ accumulation in the cytoplasm. Acidosis also activates mediators, such as phospholipaseA2, that metabolize membrane phospholipids to arachidonic acid, a precursor of inflammatory mediators such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins. Ischemia will also initiate conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase [13].

Reperfusion is able to prevent the irreversible damages of ischemia. Nevertheless, this process also generates lesions that aggravate the pre-existing tissue damages. At the cellular level, reoxygenation interrupts the lesions induced by ischemia, but causes reperfusion injury. During the first few minutes of reperfusion, the rapid correction of acidosis increases the cytosolic Ca2+, thus promoting the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore [14]. This opening causes a sudden change in the mitochondrial membrane permeability, resulting in energy collapse incompatible with cell survival and inducing the release of pro-apoptotic factors from the inter-membrane mitochondrial space to the cytosol, leading to cell death. It is the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

In parallel, reperfusion generates massive oxidative stress since xanthine oxidase and succinate, produced during ischemia, catalyzes the formation of uric acid from hypoxanthine and of ubiquinol, respectively, accompanied by the formation of large amounts of free radicals. Very interestingly, Chouchani et al. demonstrated a conserved metabolic response of tissues to ischemia-reperfusion (IR) revealing that reducing ischemia-induced succinate increase and its oxidation after reperfusion might be an important therapeutic during IR settings. [15,16,17].

The ROS thus produced exceed the cellular antioxidant defenses creating a vicious circle. Production of free radicals will cause a dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which in turn generate more ROS. Such ROS overproduction leads to several deleterious effects: lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA mutations, but also to the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore.

3. Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacities in PAD

3.1. Experimental Data

Impairments in mitochondrial respiration were observed in both claudicating and CLTI experimental models. Indeed, significant reduction in mitochondrial complexes I, II and IV activities was found in muscles of rats submitted to hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion compared to contralateral muscles [18,19,20,21]. Similarly, mouse models of CLTI presented decreased activities of the complexes I, III and IV in ischemic muscles compared with controls [22].

The respiratory impairments were shown to be strain-, muscle-, age- and disease- specific. Indeed, mitochondrial respiration was affected by hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion in limb muscles of BALB/c mice, but not of C57BL/6 mice [23]. Secondly, ischemia-reperfusion injury was shown to affect more severely the respiration in glycolytic muscles than in oxidative ones [24]. Furthermore, the impairments in mitochondrial respiration observed in young mice were greater in older animals submitted to ischemia-reperfusion injury [25]. Lastly, the decline in mitochondrial oxidative capacity was more severe in diabetic rats compared to non-diabetic animals (Table 1) [26].

Table 1.

Mitochondrial oxidative capacity and peripheral arterial disease in selected experimental studies.

3.2. Clinical Data

Oxygraphy measurements in PAD patients revealed significantly altered respiratory activity, notably of complexes I, III and IV, and of the acceptor control ratio [27,28,29,30]. Interestingly, more recent studies reported no difference in the mitochondrial respiration rate between PAD patients and healthy controls, despite alterations in O2 delivery, tissue-reoxygenation and ATP synthesis rate during exercise [31,32]. These conflicting findings could be explained by disparities in disease severity. Indeed, the alterations in mitochondrial oxidative capacity may have been the result of factors associated with higher morbidity in PAD, such as sarcopenia [33,34,35].

Mitochondrial energy metabolism was shown to decrease in PAD patients compared to controls [36,37]. In contrast, Hou et al. found similar mitochondrial ATP production rate in both PAD patients and healthy controls [38]. Again, such differences might be explained by differences in disease severity or morbidity factors rate.

It is important to note that patients suffering from both PAD and type II diabetes (DT2) are more susceptible to reduced O2 consumption and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation compared to patients with PAD alone or to controls (Table 2) [39,40].

Table 2.

Mitochondrial oxidative capacities and peripheral arterial disease in clinical studies.

4. Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Proteins, Lipids and DNA Alterations and Impaired Antioxidant Defense, in PAD

The interaction between mitochondria and oxidative stress in skeletal muscle is modulated by repeated cycles of ischemia-reperfusion in the context of PAD. The vascular damages create an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand during efforts, generating a situation of ischemia; followed by a situation of reperfusion when the patient is at rest. Repetition of ischemia and reperfusion cycles are deleterious for skeletal muscle and lead to myopathy and to remote organ damage [7,28,41].

4.1. Experimental Data

ROS production was found increased in both animal models of PAD (acute ischemia-reperfusion and CLTI) as compared to controls, using either measurements of 1) free radical species by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, 2) dihydroethidium (DHE) by epifluorescence microscopy or 3) H2O2 by Amplex Red perioxide assay [24,42,43]. Interestingly, ROS production was greater in PAD animals presenting with hypercholesterolemia or diabetes [26,44]. These evidences suggest an association between PAD comorbidity factors and enhanced mitochondrial dysfunction.

Furthermore, deleterious effects of oxidative stress were also observed in ischemic skeletal muscles, as highlighted by higher levels of oxidative stress markers (superoxide dismutase [45], protein carbonyls and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenanal protein (HNE) adducts) [22], and elevated DNA alterations [46].

Finally, antioxidant defenses have been shown to be impaired by ischemia-reperfusion. Indeed, alterations in the expression of superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 (SOD1 and SOD2), catalase and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) were observed in ischemic muscles compared with controls (Table 3) [22,45,47].

Table 3.

Reactive oxygen species production during peripheral arterial disease in experimental studies.

4.2. Clinical Data

Similar to the findings on experimental models, PAD patients displayed increased mitochondria-derived ROS production characterized by elevated levels of free radical species [32].

Moreover, oxidative damages were also observed in patients suffering from PAD, as reported by higher levels of oxidative stress markers (protein carbonyl groups, HNE-protein adducts and lipid hydroperoxides), and elevated DNA alterations [28,49,50,51,52,53].

Lastly, evidence of reduced antioxidant defenses has been shown in PAD patients, notably with altered activities of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase (Table 4) [28].

Table 4.

Reactive oxygen species production during peripheral arterial disease in clinical studies.

5. Mitochondrial Implication in Apoptosis during PAD

5.1. Experimental Data

Rodent models of PAD displayed elevated protein expression of the apoptotic factors cleaved-caspase 3, cleaved-poly (ADP-robose) polymerase (PARD) and mitochondrial and cytosolic Bcl2-associated X (Bax), and reduced protein expression of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2, compared with controls [21,54,55]. Furthermore, a decrease in mitochondrial calcium retention capacity was observed in ischemic limbs compared with contralateral ones (Table 5) [25,44,47,56,57].

Table 5.

Mitochondrial implication in apoptosis during peripheral arterial disease in experimental studies.

5.2. Clinical Data

Human investigations also showed a clear implication of apoptosis in PAD pathophysiology. Indeed, PAD patients displayed elevated levels of genes mediating apoptosis [58], increased DNA fragmentation and caspase-3 activity [59]. Additionally, multiple studies reported higher levels of apoptotic cells in different cell types, notably endothelial cells and lymphocytes [60,61]. Interestingly, another study reported similar levels of endothelial apoptosis in both PAD and control groups. This result is likely due to disparities in patient’s selection, with patients presenting with lower associated risk factors (Table 6) [62].

Table 6.

Mitochondrial implication in apoptosis during peripheral arterial disease in clinical studies.

6. Conclusions

In summary, PAD is a public health issue even when poorly symptomatic [63], and mitochondria are importantly involved in its pathophysiology. Not only because mitochondrial alterations reduce the energy available for cell function, but also because mitochondria participate in the increased ROS production (and therefore to a greater oxidative stress) and in the enhanced opening of the mitochondrial permeability pore which favor the intrinsic pathway of cell apoptosis. These data account for the fact that skeletal muscle mitochondrial function might be considered as a prognostic factor in the setting of PAD in humans. On the other hand, if ROS production remains contained below a certain threshold, mitohormesis and stimulation of the antioxidant defenses can be protective supporting that mitochondrial function modulation might be a therapeutic target. Thus, further studies focused on mitochondria are warranted to optimize the care of patients presenting with PAD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., A.-L.C., A.L., and B.G.; methodology, M.P., M.R., A.-L.C., A.L., and B.G.; validation, M.P., M.R., A.-L.C., S.T., A.M., E.A., N.C., A.L., and B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., A.L., and B.G. writing—review and editing, M.P., N.C. A.L. and B.G.; supervision, A.L. and B.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Criqui, M.H.; Aboyans, V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1509–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, S.; Mafilios, M.S.; Bhounsule, P.; Hasegawa, J.T. The burden of critical limb ischemia: A review of recent literature. Vasc. Health. Risk. Manag. 2019, 15, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, A.; Lee, C.J. Epidemiology of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Critical Limb Ischemia. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 19, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leardini-Tristao, M.; Charles, A.L.; Lejay, A.; Pizzimenti, M.; Meyer, A.; Estato, V.; Tibiriçá, E.; Andres, E.; Geny, B. Beneficial Effect of Exercise on Cognitive Function during Peripheral Arterial Disease: Potential Involvement of Myokines and Microglial Anti-Inflammatory Phenotype Enhancement. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboyans, V.; Ricco, J.B.; Bartelink, M.L.E.L.; Björck, M.; Brodmann, M.; Cohnert, T.; Collet, J.P.; Czerny, M.; De Carlo, M.; Debus, S.; et al. Editor’s Choice—2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 55, 305–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.S.; Bradbury, A.W.; Kolh, P.; White, J.V.; Dick, F.; Fitridge, R.; Mills, J.L.; Ricco, J.B.; Suresh, K.R.; Murad, M.H.; et al. Global Vascular Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 58, S1–S109.e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Charles, A.L.; Meyer, A.; Lejay, A.; Scholey, J.W.; Chakfé, N.; Zoll, J.; Geny, B. Chronology of mitochondrial and cellular events during skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2016, 310, C968–C982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutakis, P.; Ismaeel, A.; Farmer, P.; Purcell, S.; Smith, R.S.; Eidson, J.L.; Bohannon, W.T. Oxidative stress and antioxidant treatment in patients with peripheral artery disease. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.E. ATP Synthesis by Rotary Catalysis (Nobel lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 1998, 37, 2308–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.E.; Dickson, V.K. The peripheral stalk of the mitochondrial ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 2006, 1757, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.E. The ATP synthase: The understood, the uncertain and the unknown. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejay, A.; Meyer, A.; Schlagowski, A.I.; Charles, A.L.; Singh, F.; Bouitbir, J.; Pottecher, J.; Chakfé, N.; Zoll, J.; Geny, B. Mitochondria: Mitochondrial participation in ischemia-reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 50, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, K.I.; Nella, A.A.; Zhu, Z.; Swanson, S.A.; Casale, G.P.; Gutti, T.L.; Judge, A.R.; Pipinos, I.I. Mitochondriopathy of peripheral arterial disease. Vascular 2007, 15, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: A mystery solved? Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; James, A.M.; Work, L.M.; Saeb-Parsy, K.; Frezza, C.; Krieg, T.; Murphy, M.P. A Unifying Mechanism for Mitochondrial Superoxide Production during Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijević, D.; Sundier, S.Y.; Robb, E.L.; Logan, A.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Ord, E.N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2014, 515, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Methner, C.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Logan, A.; Pell, V.R.; Ding, S.; James, A.M.; Cochemé, H.M.; Reinhold, J.; Lilley, K.S.; et al. Cardioprotection by S-nitrosation of a cysteine switch on mitochondrial complex I. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottecher, J.; Kindo, M.; Chamaraux-Tran, T.N.; Charles, A.L.; Lejay, A.; Kemmel, V.; Vogel, T.; Chakfe, N.; Zoll, J.; Diemunsch, P.; et al. Skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury and cyclosporine A in the aging rat. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 30, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaveau, F.; Zoll, J.; Bouitbir, J.; N’guessan, B.; Plobner, P.; Chakfe, N.; Kretz, J.G.; Richard, R.; Piquard, F.; Geny, B. Effect of chronic pre-treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on skeletal muscle mitochondrial recovery after ischemia/reperfusion. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 24, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, M.L.; Roselino, J.E.S.; Piccinato, C.E.; Cherri, J. Mitochondrial alterations in skeletal muscle submitted to total ischemia. J. Surg. Res. 2003, 110, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, Z.; Bouitbir, J.; Charles, A.L.; Talha, S.; Kindo, M.; Pottecher, J.; Zoll, J.; Geny, B. Remote and local ischemic preconditioning equivalently protects rat skeletal muscle mitochondrial function during experimental aortic cross-clamping. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 55, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pipinos, I.I.; Swanson, S.A.; Zhu, Z.; Nella, A.A.; Weiss, D.J.; Gutti, T.L.; McComb, R.D.; Baxter, B.T.; Lynch, T.G.; Casale, G.P. Chronically ischemic mouse skeletal muscle exhibits myopathy in association with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 295, R290–R296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.A.; Ryan, T.E.; Lin, C.T.; Inigo, M.M.R.; Green, T.D.; Brault, J.J.; Spangenburg, E.E.; McClung, J.M. Diminished force production and mitochondrial respiratory deficits are strain-dependent myopathies of subacute limb ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 1504–1514.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, A.L.; Guilbert, A.S.; Guillot, M.; Talha, S.; Lejay, A.; Meyer, A.; Kindo, M.; Wolff, V.; Bouitbir, J.; Zoll, J.; et al. Muscles Susceptibility to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injuries Depends on Fiber Type Specific Antioxidant Level. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Charles, A.L.; Georg, I.; Goupilleau, F.; Meyer, A.; Kindo, M.; Laverny, G.; Metzger, D.; Geny, B. Aging Exacerbates Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Mitochondrial Respiration Impairment in Skeletal Muscle. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottecher, J.; Adamopoulos, C.; Lejay, A.; Bouitbir, J.; Charles, A.L.; Meyer, A.; Singer, M.; Wolff, V.; Diemunsch, P.; Laverny, G.; et al. Diabetes Worsens Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis After Lower-Limb Ischemia-Reperfusion: Implication of the RISK and SAFE Pathways? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutakis, P.; Miserlis, D.; Myers, S.A.; Kim, J.K.S.; Zhu, Z.; Papoutsi, E.; Swanson, S.A.; Haynatzki, G.; Ha, D.M.; Carpenter, L.A.; et al. Abnormal accumulation of desmin in gastrocnemius myofibers of patients with peripheral artery disease: Associations with altered myofiber morphology and density, mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired limb function. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2015, 63, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipinos, I.I.; Judge, A.R.; Zhu, Z.; Selsby, J.T.; Swanson, S.A.; Johanning, J.M.; Baxter, B.T.; Lynch, T.G.; Dodd, S.L. Mitochondrial defects and oxidative damage in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipinos, I.I.; Sharov, V.G.; Shepard, A.D.; Anagnostopoulos, P.V.; Katsamouris, A.; Todor, A.; Filis, K.A.; Sabbah, H.N. Abnormal mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 38, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, E.P.; Hiatt, W.R.; Gardner, A.W.; Hoppel, C.L. Decreased NADH dehydrogenase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase in peripheral arterial disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 280, H603–H609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.R.; Layec, G.; Trinity, J.D.; Le Fur, Y.; Gifford, J.R.; Clifton, H.L.; Richardson, R.S. Oxygen availability and skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in patients with peripheral artery disease: Implications from in vivo and in vitro assessments. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H897–H909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, C.R.; Layec, G.; Trinity, J.D.; Kwon, O.S.; Zhao, J.; Reese, V.R.; Gifford, J.R.; Richardson, R.S. Increased skeletal muscle mitochondrial free radical production in peripheral arterial disease despite preserved mitochondrial respiratory capacity. Exp. Physiol. 2018, 103, 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisaki, K.; Furuyama, T.; Matsubara, Y.; Inoue, K.; Kurose, S.; Yoshino, S.; Nakayama, K.; Yamashita, S.; Yoshiya, K.; Yoshiga, R.; et al. External validation of CLI Frailty Index and assessment of predictive value of modified CLI Frailty Index for patients with critical limb ischemia undergoing infrainguinal revascularization. Vascular 2019, 1708538119836005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, R.; Deguchi, J.; Hashimoto, T.; Sato, O. Sarcopenia as a Possible Negative Predictor of Limb Salvage in Patients with Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2019, 12, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Aoyagi, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Okadome, J.; Morisaki, K.; Shirabe, K.; Maehara, Y. Sarcopenia is a prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with critical limb ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlGhatrif, M.; Zane, A.; Oberdier, M.; Canepa, M.; Studenski, S.; Simonsick, E.; Spencer, R.G.; Fishbein, K.; Reiter, D.; Lakatta, E.G.; et al. Lower Mitochondrial Energy Production of the Thigh Muscles in Patients with Low-Normal Ankle-Brachial Index. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipinos, I.I.; Shepard, A.D.; Anagnostopoulos, P.V.; Katsamouris, A.; Boska, M.D. Phosphorus 31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy suggests a mitochondrial defect in claudicating skeletal muscle. J. Vasc. Surg. 2000, 31, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.Y.; Green, S.; Askew, C.D.; Barker, G.; Green, A.; Walker, P.J. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial ATP production rate and walking performance in peripheral arterial disease. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2002, 22, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindegaard, B.P.; Bækgaard, N.; Quistorff, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in calf muscles of patients with combined peripheral arterial disease and diabetes type 2. Int. Angiol. 2017, 36, 482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Tecilazich, F.; Dinh, T.; Lyons, T.E.; Guest, J.; Villafuerte, R.A.; Sampanis, C.; Gnardellis, C.; Zuo, C.S.; Veves, A. Postexercise phosphocreatine recovery, an index of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, is reduced in diabetic patients with lower extremity complications. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release: An update and review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006, 1757, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejay, A.; Choquet, P.; Thaveau, F.; Singh, F.; Schlagowski, A.; Charles, A.L.; Laverny, G.; Metzger, D.; Zoll, J.; Chakfe, N.; et al. A new murine model of sustainable and durable chronic critical limb ischemia fairly mimicking human pathology. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015, 49, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, B.; Kang, C.; Kim, J.; Yoo, D.; Cho, B.R.; Kang, P.M.; Lee, D. H2O2-responsive antioxidant polymeric nanoparticles as therapeutic agents for peripheral arterial disease. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 511, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejay, A.; Charles, A.L.; Georg, I.; Goupilleau, F.; Delay, C.; Talha, S.; Thaveau, F.; Chakfe, N.; Geny, B. Critical limb ischemia exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction in ApoE-/- mice compared to ApoE+/+ mice, but N-acetyl cysteine still confers protection. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 58, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.P.; Tu, H.; Pipinos, I.I.; Muelleman, R.L.; Albadawi, H.; Li, Y.L. Tourniquet-induced acute ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse skeletal muscles: Involvement of superoxide. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 650, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miura, S.; Saitoh, S.; Kokubun, T.; Owada, T.; Yamauchi, H.; Machii, H.; Takeishi, Y. Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidant Maintains Blood Flow, Mitochondrial Function, and Redox Balance in Old Mice Following Prolonged Limb Ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejay, A.; Laverny, G.; Paradis, S.; Schlagowski, A.I.; Charles, A.L.; Singh, F.; Zoll, J.; Thaveau, F.; Lonsdorfer, E.; Dufour, S.; et al. Moderate Exercise Allows for shorter Recovery Time in Critical Limb Ischemia. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, M.; Charles, A.L.; Chamaraux-Tran, T.N.; Bouitbir, J.; Meyer, A.; Zoll, J.; Schneider, F.; Geny, B. Oxidative stress precedes skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction during experimental aortic cross-clamping but is not associated with early lung, heart, brain, liver, or kidney mitochondrial impairment. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 1043–1051.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.M.; Peterson, C.A.; Sufit, R.; Ferrucci, L.; Guralnik, J.M.; Kibbe, M.R.; Polonsky, T.S.; Tian, L.; Criqui, M.H.; Zhao, L.; et al. Peripheral artery disease, calf skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA copy number, and functional performance. Vasc. Med. 2018, 23, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutakis, P.; Weiss, D.J.; Miserlis, D.; Shostrom, V.K.; Papoutsi, E.; Ha, D.M.; Carpenter, L.A.; McComb, R.D.; Casale, G.P.; Pipinos, I.I. Oxidative damage in the gastrocnemius of patients with peripheral artery disease is myofiber type selective. Redox. Biol. 2014, 2, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Casale, G.P.; Koutakis, P.; Nella, A.A.; Swanson, S.A.; Zhu, Z.; Miserlis, D.; Johanning, J.M.; Pipinos, I.I. Oxidative damage and myofiber degeneration in the gastrocnemius of patients with peripheral arterial disease. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brass, E.P.; Wang, H.; Hiatt, W.R. Multiple skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA deletions in patients with unilateral peripheral arterial disease. Vasc. Med. 2000, 5, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, H.K.; Hiatt, W.R.; Hoppel, C.L.; Brass, E.P. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA injury in patients with unilateral peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 1999, 99, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, S.L.; Yin, T.C.; Shao, P.L.; Chen, K.H.; Wu, R.W.; Chen, C.C.; Lin, P.Y.; Chung, S.Y.; Sheu, J.J.; Sung, P.H.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen facilitates the effect of endothelial progenitor cell therapy on improving outcome of rat critical limb ischemia. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 1948–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu, J.J.; Lee, F.Y.; Wallace, C.G.; Tsai, T.H.; Leu, S.; Chen, Y.L.; Chai, H.T.; Lu, H.I.; Sun, C.K.; Yip, H.K. Administered circulating microparticles derived from lung cancer patients markedly improved angiogenesis, blood flow and ischemic recovery in rat critical limb ischemia. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tetsi, L.; Charles, A.L.; Georg, I.; Goupilleau, F.; Lejay, A.; Talha, S.; Maumy-Bertrand, M.; Lugnier, C.; Geny, B. Effect of the Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitor Sildenafil on Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Muscle Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejay, A.; Paradis, S.; Lambert, A.; Charles, A.L.; Talha, S.; Enache, I.; Thaveau, F.; Chakfe, N.; Geny, B. N-Acetyl Cysteine Restores Limb Function, Improves Mitochondrial Respiration, and Reduces Oxidative Stress in a Murine Model of Critical Limb Ischaemia. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 56, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, R.; Shameer, K.; Dhar, A.; Ding, K.; Kullo, I.J. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in the setting of peripheral arterial disease. J. Clin. Bioinforma. 2012, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.G.; Duscha, B.D.; Robbins, J.L.; Redfern, S.I.; Chung, J.; Bensimhon, D.R.; Kraus, W.E.; Hiatt, W.R.; Regensteiner, J.G.; Annex, B.H. Increased levels of apoptosis in gastrocnemius skeletal muscle in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc. Med. 2007, 12, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A.W.; Parker, D.E.; Montgomery, P.S.; Sosnowska, D.; Casanegra, A.I.; Ungvari, Z.; Csiszar, A.; Sonntag, W.E. Greater Endothelial Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skórkowska-Telichowska, K.; Adamiec, R.; Tuchendler, D.; Gasiorowski, K. Susceptibility to apoptosis of lymphocytes from patients with peripheral arterial disease. Clin. Investig. Med. 2009, 32, E345–E351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.W.; Parker, D.E.; Montgomery, P.S.; Sosnowska, D.; Casanegra, A.I.; Esponda, O.L.; Ungvari, Z.; Csiszar, A.; Sonntag, W.E. Impaired vascular endothelial growth factor A and inflammation in patients with peripheral artery disease. Angiology 2014, 65, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves-Cabratosa, L.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Comas-Cufí, M.; Blanch, J.; Ponjoan, A.; Martí-Lluch, R.; Elosua-Bayes, M.; Parramon, D.; Camós, L.; Ramos, R. Role of Low Ankle-Brachial Index in Cardiovascular and Mortality Risk Compared with Major Risk Conditions. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).