Perinatal Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of an Australian Population-Based Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

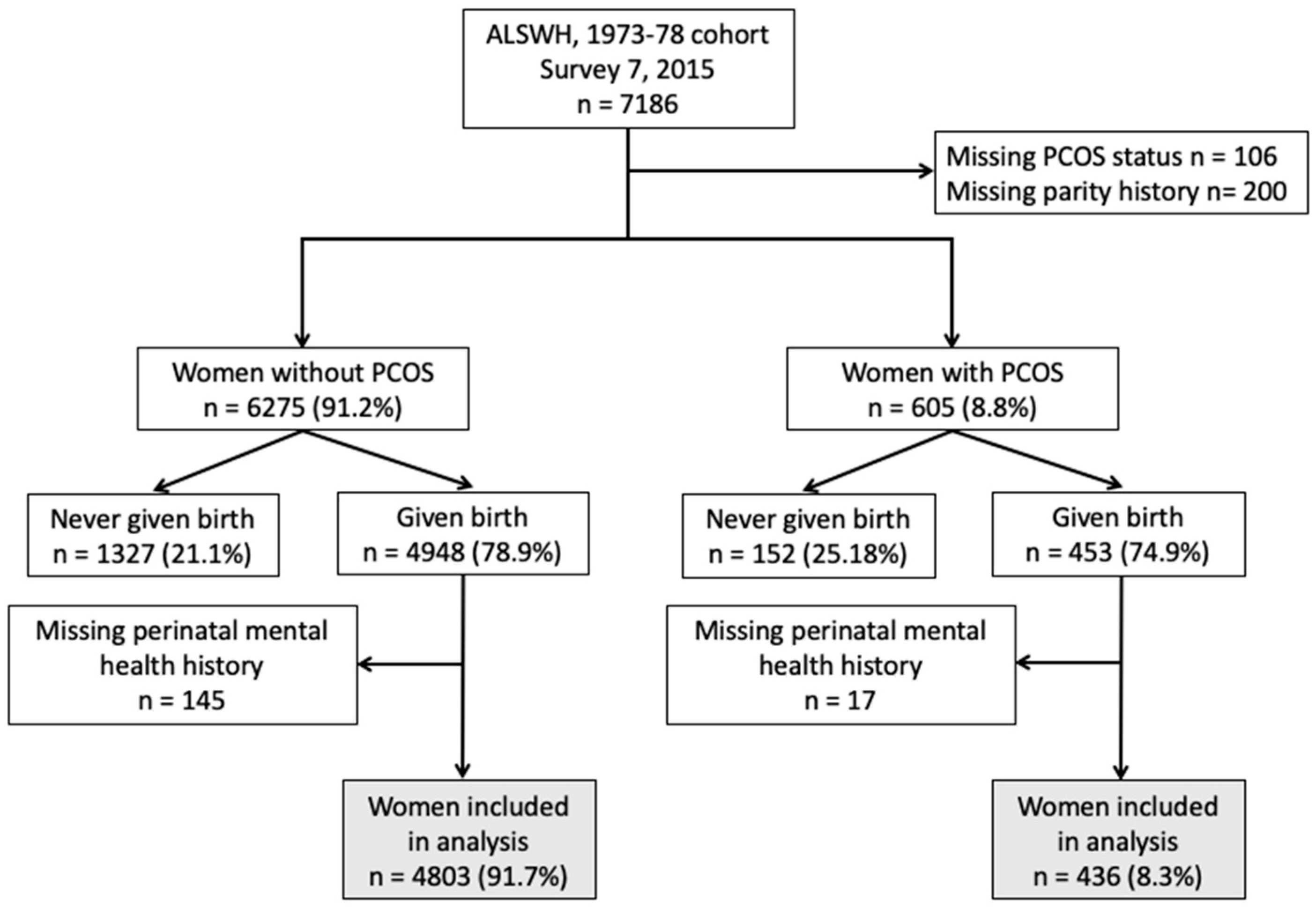

2.1. Study Population and Methods

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Variables

2.2.2. Explanatory Variables

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Their Characteristics

3.2. Reproductive History and Their Relationship with PCOS

3.3. Obstetric Complications and Their Relationship with PCOS

3.4. Common Perinatal Mental Disorders and Their Relationship with PCOS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, J.; Cabral de Mello, M.; Patel, V.; Rahman, A.; Tran, T.; Holton, S.; Holmes, W. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 139G–149G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, N.I.; Gaynes, B.N.; Lohr, K.N.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Gartlehner, G.; Swinson, T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Wisner, K.L. Perinatal mental illness: Definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grote, N.K.; Bridge, J.A.; Gavin, A.R.; Melville, J.L.; Iyengar, S.; Katon, W.J. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.X.; Wu, Y.L.; Xu, S.J.; Zhu, R.P.; Jia, X.M.; Zhang, S.F.; Huang, K.; Zhu, P.; Hao, J.H.; Tao, F.B. Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriadis, S.; VonderPorten, E.H.; Mamisashvili, L.; Tomlinson, G.; Dennis, C.L.; Koren, G.; Steiner, M.; Mousmanis, P.; Cheung, A.; Radford, K.; et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e321–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarde, A.; Morais, M.; Kingston, D.; Giallo, R.; MacQueen, G.M.; Giglia, L.; Beyene, J.; Wang, Y.; McDonald, S.D. Neonatal outcomes in women with untreated antenatal depression compared with women without depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurki, T.; Hiilesmaa, V.; Raitasalo, R.; Mattila, H.; Ylikorkala, O. Depression and anxiety in early pregnancy and risk for preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, C.; Williams, M.A.; Calderon-Margalit, R.; Cripe, S.M.; Sorensen, T.K. Preeclampsia risk in relation to maternal mood and anxiety disorders diagnosed before or during early pregnancy. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009, 22, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Gaffan, E.A. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2000, 41, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Paglia, A.; Coolbear, J.; Niccols, A.; Parker, K.C.; Guger, S. Attachment security: A meta-analysis of maternal mental health correlates. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 1019–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlby, S.; Hay, D.F.; Sharp, D.; Waters, C.S.; O’Keane, V. Antenatal depression predicts depression in adolescent offspring: Prospective longitudinal community-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 113, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korhonen, M.; Luoma, I.; Salmelin, R.; Tamminen, T. A longitudinal study of maternal prenatal, postnatal and concurrent depressive symptoms and adolescent well-being. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.M.; Evans, J.; Kounali, D.; Lewis, G.; Heron, J.; Ramchandani, P.G.; O’Connor, T.G.; Stein, A. Maternal depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period: Risks and possible mechanisms for offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeek, T.; Bockting, C.L.; van Pampus, M.G.; Ormel, J.; Meijer, J.L.; Hartman, C.A.; Burger, H. Postpartum depression predicts offspring mental health problems in adolescence independently of parental lifetime psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, M.M.; Wickramaratne, P.; Nomura, Y.; Warner, V.; Pilowsky, D.; Verdeli, H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.M.; Bornstein, M.H.; Cordero, M.; Scerif, G.; Mahedy, L.; Evans, J.; Abioye, A.; Stein, A. Maternal perinatal mental health and offspring academic achievement at age 16: The mediating role of childhood executive function. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2016, 57, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.L.; Dowswell, T. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Rossom, R.C.; Henninger, M.; Groom, H.C.; Burda, B.U. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: Evidence report and systematic review for the us preventive services task force. JAMA 2016, 315, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, C.; Ossola, P.; Amerio, A.; Daniel, B.D.; Tonna, M.; De Panfilis, C. Clinical management of perinatal anxiety disorders: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Broth, M.R.; Hall, C.M.; Stowe, Z.N. Treatment of postpartum depression in mothers: Secondary benefits to the infants. Infant. Ment. Health J. Off. Publ. World Assoc. Infant Ment. Health 2008, 29, 492–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, T.; Perantie, D.C.; Nix, B.D.; Barnes, L.D.; Mostello, D.J.; Holcomb, W.L.; Svrakic, D.M.; Scherrer, J.F.; Lustman, P.J.; Hershey, T. Treating prepartum depression to improve infant developmental outcomes: A study of diabetes in pregnancy. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2012, 19, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.; Cooper, P.J.; Wilson, A.; Romaniuk, H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression: 2. Impact on the mother-child relationship and child outcome. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 182, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Oram, S.; Galley, H.; Trevillion, K.; Feder, G. Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, C.A.; Gold, K.J.; Flynn, H.A.; Yoo, H.; Marcus, S.M.; Davis, M.M. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigod, S.N.; Villegas, L.; Dennis, C.L.; Ross, L.E. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: A systematic review. BJOG 2010, 117, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, E.; Grace, S.; Wallington, T.; Stewart, D.E. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.E.; McQueen, K.; Vigod, S.; Dennis, C.L. Risk for postpartum depression associated with assisted reproductive technologies and multiple births: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2011, 17, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, F.; Agostini, F.; Paterlini, M.; Andrei, F.; De Pascalis, L.; Palomba, S.; La Sala, G.B. Effects of assisted reproductive technology and of women’s quality of life on depressive symptoms in the early postpartum period: A prospective case-control study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2015, 31, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, F.; Agostini, F.; Fagandini, P.; La Sala, G.B.; Blickstein, I. Depressive symptoms during late pregnancy and early parenthood following assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos). Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozdag, G.; Mumusoglu, S.; Zengin, D.; Karabulut, E.; Yildiz, B.O. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2841–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, E.W.; Tay, C.T.; Hiam, D.S.; Teede, H.J.; Moran, L.J. Comorbidities and complications of polycystic ovary syndrome: An overview of systematic reviews. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 2018, 89, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, T.R.; Morgan, C.L.; Berni, E.R.; Rees, D.A. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with adverse mental health and neurodevelopmental outcomes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damone, A.L.; Joham, A.E.; Loxton, D.; Earnest, A.; Teede, H.J.; Moran, L.J. Depression, anxiety and perceived stress in women with and without pcos: A community-based study. Psychol. Med. 2018, 49, 1510–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.H.; Hu, L.Y.; Tsai, S.J.; Yang, A.C.; Huang, M.W.; Chen, P.M.; Wang, S.L.; Lu, T.; Shen, C.C. Risk of psychiatric disorders following polycystic ovary syndrome: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesta, C.E.; Mansson, M.; Palm, C.; Lichtenstein, P.; Iliadou, A.N.; Landen, M. Polycystic ovary syndrome and psychiatric disorders: Co-morbidity and heritability in a nationwide swedish cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 73, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J.; International, P.N. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1602–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokras, A.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Yildiz, B.O.; Li, R.; Ottey, S.; Shah, D.; Epperson, N.; Teede, H. Androgen excess- polycystic ovary syndrome society: Position statement on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and eating disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joham, A.E.; Teede, H.J.; Ranasinha, S.; Zoungas, S.; Boyle, J. Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Data from a large community-based cohort study. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015, 24, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, C.M.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Hughes, E.G.; Visser, G.H.; Fauser, B.C.; Macklon, N.S. A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. Update 2006, 12, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, W.A.; Whitrow, M.J.; Davies, M.J.; Fernandez, R.C.; Moore, V.M. Postnatal depression in a community-based study of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Dobson, A.J.; Brown, W.J.; Bryson, L.; Byles, J.; Warner-Smith, P.; Young, A.F. Cohort profile: The australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loxton, D.; Tooth, L.; Harris, M.L.; Forder, P.M.; Dobson, A.; Powers, J.; Brown, W.; Byles, J.; Mishra, G. Cohort profile: The australian longitudinal study on women’s health (alswh) 1989-95 cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 391e–392e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Joham, A.E.; Paul, E.; Moran, L.J.; Loxton, D.; Jolley, D.; Lombard, C. Longitudinal weight gain in women identified with polycystic ovary syndrome: Results of an observational study in young women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013, 21, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a who consultation. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2000, 894, 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, N.W.; Brown, W.; Dobson, A. Accuracy of body mass index estimated from self-reported height and weight in mid-aged australian women. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The mos social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.; Deeks, A.; Moran, L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: A complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejbaek, C.S.; Pinborg, A.; Hageman, I.; Forman, J.L.; Hougaard, C.O.; Schmidt, L. Are repeated assisted reproductive technology treatments and an unsuccessful outcome risk factors for unipolar depression in infertile women? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, C.A.; Ungerer, J.A.; Beaurepaire, J.; Tennant, C.; Saunders, D. Anxiety during pregnancy and fetal attachment after in-vitro fertilization conception. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 12, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repokari, L.; Punamaki, R.L.; Poikkeus, P.; Vilska, S.; Unkila-Kallio, L.; Sinkkonen, J.; Almqvist, F.; Tiitinen, A.; Tulppala, M. The impact of successful assisted reproduction treatment on female and male mental health during transition to parenthood: A prospective controlled study. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 3238–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatziandreou, M.; Madianos, M.G.; Farsaliotis, V.C. Psychological and personality factors and in vitro fertilization treatment in women. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2003, 17, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Gressier, F.; Letranchant, A.; Cazas, O.; Sutter-Dallay, A.L.; Falissard, B.; Hardy, P. Post-partum depressive symptoms and medically assisted conception: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 2575–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Blanco, A.; Diago, V.; Hervas, D.; Ghosn, F.; Vento, M.; Chafer-Pericas, C. Anxiety and depressive symptoms, and stress biomarkers in pregnant women after in vitro fertilization: A prospective cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Bishai, D.; Minkovitz, C.S. Multiple births are a risk factor for postpartum maternal depressive symptoms. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, C.; Cox, S.; Oates, M.; Ndukwe, G.; Glazebrook, C. Impact of a multiple, ivf birth on post-partum mental health: A composite analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 2058–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilska, S.; Unkila-Kallio, L.; Punamaki, R.L.; Poikkeus, P.; Repokari, L.; Sinkkonen, J.; Tiitinen, A.; Tulppala, M. Mental health of mothers and fathers of twins conceived via assisted reproduction treatment: A 1-year prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, F.; Karaderi, T.; Jones, M.R.; Meun, C.; He, C.; Drong, A.; Kraft, P.; Lin, N.; Huang, H.; Broer, L.; et al. Large-scale genome-wide meta-analysis of polycystic ovary syndrome suggests shared genetic architecture for different diagnosis criteria. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, A.L.; Force, U.S.P.S.T.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Grossman, D.C.; Baumann, L.C.; Davidson, K.W.; Ebell, M.; Garcia, F.A.; Gillman, M.; Herzstein, J.; et al. Screening for depression in adults: Us preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016, 315, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.P.; Highet, N.; The Expert Working Group. Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline; Centre of Perinatal Excellence: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antenaral and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance. National Clinical Guideline Number 192; The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Overall | Non-PCOS | PCOS | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 5239 | n = 4803 (91.7%) | n = 436 (8.3%) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 39.7 ± 1.5 | 39.7 ± 1.5 | 39.6 ± 1.4 | 0.058 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 26.7 ± 6.3 | 26.4 ± 6.0 | 29.3 ± 7.7 | <0.001 |

| BMI category n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight | 95 (1.8) | 87 (1.8) | 8 (1.9) | |

| Healthy | 2389 (46.4) | 2255 (47.8) | 134 (31.2) | |

| Overweight | 1428 (27.7) | 1308 (27.7) | 120 (27.9) | |

| Obese | 1241 (24.1) | 1073 (22.7) | 168 (39.1) | |

| Missing | 86 (1.6) | 80 (1.7) | 6 (1.4) | |

| Education level n (%) | 0.457 | |||

| Year 12 or less | 837 (16.2) | 768 (16.3) | 69 (16.1) | |

| Trade/apprenticeship | 122 (2.4) | 114 (2.4) | 8 (1.9) | |

| Certificate/diploma | 1300 (25.2) | 1179 (25.0) | 121 (28.2) | |

| University or higher | 1895 (56.2) | 2664 (56.4) | 231 (53.9) | |

| Missing | 85 (1.6) | 78 (1.6) | 7 (1.6) | |

| Occupation n (%) | 0.013 | |||

| Manager/administrator | 2786 (53.9) | 2554 (53.9) | 232 (53.6) | |

| Tradesperson/clerical | 1261 (24.4) | 1171 (24.7) | 90 (20.8) | |

| Transport/production/labor | 128 (2.5) | 122 (2.6) | 6 (1.4) | |

| No paid job | 998 (19.3) | 893 (18.8) | 105 (24.3) | |

| Missing | 66 (1.3) | 63 (1.3) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Marital status n (%) | 0.368 | |||

| Never married | 165 (3.2) | 147 (3.1) | 18 (4.2) | |

| Married/de facto | 4554 (88.1) | 4183 (88.3) | 371 (86.3) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 450 (8.7) | 409 (8.6) | 41 (9.5) | |

| Missing | 70 (1.3) | 64 (1.3) | 6 (1.4) | |

| Smoking status n (%) | 0.857 | |||

| Never | 3210 (61.4) | 2940 (61.4) | 270 (62.1) | |

| Ex-smoker | 1521 (29.1) | 1399 (29.2) | 122 (28.1) | |

| Active smoker | 494 (9.5) | 451 (9.4) | 43 (9.9) | |

| Missing | 14 (0.3) | 13 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Alcohol drinking pattern n (%) | 0.069 | |||

| Non-drinker | 550 (10.5) | 494 (10.3) | 56 (12.9) | |

| Low risk drinker | 4348 (83.2) | 3988 (83.2) | 360 (82.8) | |

| High risk drinker | 330 (6.3) | 311 (6.5) | 19 (4.4) | |

| Missing | 11 (0.2) | 10 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| MOS social support scale n (%) | 0.429 | |||

| High level | 3048 (59.7) | 2801 (59.9) | 247 (57.9) | |

| Moderate level | 1450 (28.4) | 1329 (28.4) | 121 (28.3) | |

| Low level | 608 (11.9) | 549 (11.7) | 59 (13.8) | |

| Missing | 133 (2.5) | 124 (2.6) | 9 (2.1) | |

| Area of residence n (%) | 0.062 | |||

| Metropolitan | 2919 (56.9) | 2653 (56.5) | 266 (62.3) | |

| Regional | 2085 (40.6) | 1932 (41.1) | 153 (35.8) | |

| Rural | 123 (2.4) | 115 (2.5) | 8 (1.9) | |

| Missing | 112 (2.1) | 103 (2.1) | 9 (2.1) | |

| Depression | 1396 (26.7) | 1224 (25.5) | 172 (39.5) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anxiety | 945 (18.0) | 825 (17.2) | 120 (27.5) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall | Non-PCOS | PCOS | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Reproductive history n (%) | |||||

| Number of live births median (IQR) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | - | - |

| Infertility | 1187 (22.7) | 925 (19.3) | 262 (60.2) | 6.3 | 5.1–7.8 |

| Fertility treatment—hormones | 383 (7.3) | 262 (5.5) | 121 (27.8) | 6.7 | 5.2–8.5 |

| Fertility treatment—IVF | 395 (7.6) | 314 (6.6) | 81 (18.6) | 3.3 | 2.5–4.3 |

| Miscarriage | 1903 (36.5) | 1713 (35.9) | 190 (43.7) | 1.4 | 1.1–1.7 |

| Termination of pregnancy | 1029 (19.8) | 958 (20.1) | 71 (16.4) | 0.8 | 0.6–1.0 |

| Pregnancy complications n (%) | |||||

| Gestational diabetes | 501 (9.6) | 430 (9.0) | 71 (16.3) | 2 | 1.5–2.6 |

| Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy | 746 (14.3) | 661 (13.8) | 85 (19.5) | 1.5 | 1.2–1.9 |

| Preterm birth (<36 weeks) | 555 (10.7) | 474 (10.0) | 81 (18.7) | 2.1 | 1.6–2.7 |

| Birth complications n (%) | |||||

| Induction of labour | 2669 (51.5) | 2439 (51.2) | 230 (53.7) | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 |

| Instrumental delivery | 1505 (29.1) | 1386 (29.2) | 119 (27.8) | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 |

| Caesarean section | 1584 (30.6) | 1427 (30.1) | 157 (36.1) | 1.3 | 1.1–1.6 |

| Low birth weight infant (<2.5 kg) | 494 (9.6) | 428 (9.0) | 66 (15.4) | 1.8 | 1.4–2.4 |

| High birth weight infant (>4 kg) | 1229 (23.8) | 1129 (23.8) | 100 (23.4) | 1 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Baby requiring SCN/NICU | 980 (18.9) | 860 (18.1) | 120 (27.1) | 1.7 | 1.4–2.2 |

| Stillbirths | 119 (2.6) | 107 (2.6) | 12 (3.2) | 1.2 | 0.7–2.3 |

| Overall | Non-PCOS | PCOS | Crude OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Antenatal depression | 248 (4.7) | 209 (4.4) | 39 (8.9) | 2.2 | 1.5–3.1 |

| Antenatal anxiety | 321 (6.1) | 270 (5.6) | 51 (11.7) | 2.2 | 1.6–3.1 |

| Antenatal depression and/or anxiety | 418 (8.0) | 354 (7.4) | 64 (14.7) | 2.2 | 1.6–2.9 |

| Combined antenatal depression and anxiety | 151 (2.9) | 125 (2.6) | 26 (6.0) | 2.4 | 1.5–3.7 |

| Postnatal depression | 1011 (19.3) | 894 (18.6) | 117 (26.8) | 1.6 | 1.3–2.0 |

| Postnatal anxiety | 658 (12.6) | 578 (12.0) | 80 (18.4) | 1.6 | 1.3–2.1 |

| Postnatal depression and/or anxiety | 1214 (23.2) | 1077 (22.4) | 137 (31.4) | 1.6 | 1.3–2.0 |

| Combined postnatal depression and anxiety | 455 (8.7) | 395 (8.2) | 60 (13.8) | 1.8 | 1.3–2.4 |

| Any common perinatal mental disorder | 1291 (24.6) | 1145 (23.8) | 146 (33.5) | 1.6 | 1.3–2.0 |

| Antenatal Depression and/or Anxiety | Postnatal Depression and/or Anxiety | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | |

| PCOS | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 0.002 | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.128 |

| Age | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.142 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.402 |

| BMI category | ||||

| Underweight | 0.8 (0.3–2.8) | 0.787 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.311 |

| Healthy | 1 | 1 | ||

| Overweight | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 0.049 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.395 |

| Obese | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 0.07 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.561 |

| Education level | ||||

| Year 12 or less | 1 | 1 | ||

| Trade/apprenticeship | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) | 0.762 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.4 |

| Certificate/diploma | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 0.889 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.746 |

| University or higher | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.29 | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.853 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Manager/administrator | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tradesperson/clerical | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) | 0.736 | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 0.657 |

| Transport/production/labor | 1.4 (0.7–3.0) | 0.372 | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | 0.923 |

| No paid job | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.011 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.066 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married/de facto | 2.8 (1.2–6.4) | 0.014 | 2.3 (1.4–3.9) | 0.001 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 1.9 (0.8–4.5) | 0.172 | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 0.08 |

| Smoking status n | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ex-smoker | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.345 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.212 |

| Active smoker | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 0.003 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.167 |

| Alcohol drinking pattern | ||||

| Non-drinker | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low risk drinker | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.109 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.342 |

| High risk drinker | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 0.354 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.733 |

| MOS social support scale | ||||

| High level | 1 | 1 | ||

| Moderate level | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.057 | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 0.013 |

| Low level | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.052 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.033 |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Metropolitan | 1 | 1 | ||

| Regional | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.06 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.681 |

| Rural | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.538 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.426 |

| Reproductive history | ||||

| Infertility | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.783 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.781 |

| Fertility treatment—hormones | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.603 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.307 |

| Fertility treatment—IVF | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.803 | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.028 |

| Miscarriage | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.946 | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.543 |

| Termination of pregnancy | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 0.839 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.862 |

| Pregnancy complications | ||||

| Gestational diabetes | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 0.479 | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.31 |

| Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy | 1.3 (0.4–1.1) | 0.057 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.363 |

| Preterm birth (<36 weeks) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.122 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.953 |

| Birth complications | ||||

| Induction of labour | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.376 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.353 |

| Instrumental delivery | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.192 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.721 |

| Caesarean section | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.656 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.881 |

| Low birth weight infant (<2.5 kg) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 0.522 | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.45 |

| High birth weight infant (>4 kg) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.135 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1 |

| Baby requiring SCN/NICU | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 0.08 | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 0.17 |

| Stillbirths | 2.1 (1.1–3.9) | 0.024 | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 0.674 |

| Pre-existing mental disorders | ||||

| Depression | 3.3 (2.5–4.3) | <0.001 | 5.3 (4.4–6.4) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 2.2 (1.7–2.9) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | <0.001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tay, C.T.; Teede, H.J.; Boyle, J.A.; Kulkarni, J.; Loxton, D.; Joham, A.E. Perinatal Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of an Australian Population-Based Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122070

Tay CT, Teede HJ, Boyle JA, Kulkarni J, Loxton D, Joham AE. Perinatal Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of an Australian Population-Based Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(12):2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122070

Chicago/Turabian StyleTay, Chau Thien, Helena J. Teede, Jacqueline A. Boyle, Jayashri Kulkarni, Deborah Loxton, and Anju E. Joham. 2019. "Perinatal Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of an Australian Population-Based Cohort" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 12: 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122070

APA StyleTay, C. T., Teede, H. J., Boyle, J. A., Kulkarni, J., Loxton, D., & Joham, A. E. (2019). Perinatal Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of an Australian Population-Based Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(12), 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122070