Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Strengths-Based Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Brief Summary of the Evidence

3. A Strengths-Based Approach and Effective Knowledge Mobilization

- Children today will have a shorter lifespan than their parents.

- If you are inactive or sedentary, your chances of dying prematurely rise markedly.

- You must attain a certain level of physical activity to achieve health benefits.

- Our children and adults are receiving failing grades with respect to physical activity participation.

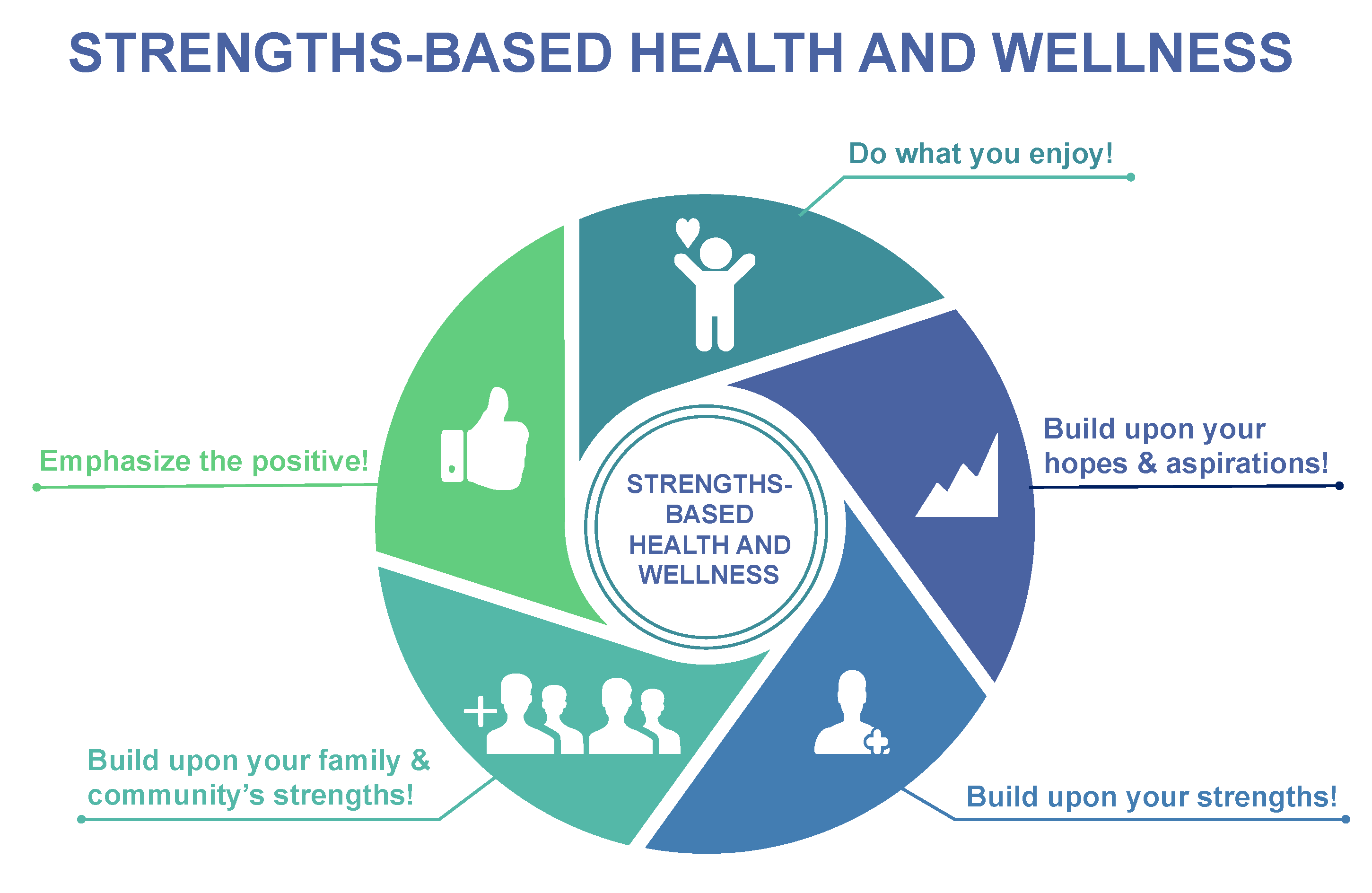

- Goal Orientation: A strengths-based approach is foremost goal-oriented and person-centered. In this phase, clients establish the goals for their life. For instance, clients could establish the goals that they would like to achieve related to physical activity, exercise, health, and wellness in their future. A practitioner can be an active participant in the discussion of these goals, but should allow clients to fully articulate their desires and aspirations [52] related to health and wellness and life in general.

- Strength Assessment: The clients are supported to recognize the inherent strengths and resources at their disposal that can be used to offset any difficulty or condition. This often relates to current strengths; however, the past may be mined for previous strengths (assets, talents, resources) that may have been lost or forgotten. It is essential to focus on the strengths of each person and not on the problems, deficits, or disease condition [52]. For example, clients that aspire to become healthier can recognize the activities that they enjoy, what works for them, and the opportunities for doing these activities with their family and within their community.

- Resources from the Environment: This refers to how a person’s environment can be rich in resources that allow the client to achieve his/her aspirations. This includes individuals, groups, associations, and institutions that may provide resources and/or support for the client. A practitioner can serve as the conduit (linkage) to these resources [52]. For instance, a client desiring to become more physically active may contact a qualified exercise professional to determine the resources available within the community related to physical activity. The exercise professional can assist the client in identifying the opportunities and resources available for becoming more physically active [31].

- Explicit Methods Are Used for Identifying Client and Environmental Strengths for Goal Attainment: There are a variety of strengths-based approaches to meet the goals and aspirations of the client. There will be subtle differences in how each of the strengths-based techniques will be applied [52]. For instance, solution-focused therapy has been increasingly used within clinical settings [50], wherein clients will set goals and then identify relevant strengths (such as what works now, what may work in the future) [52]. In strengths-based case management approaches, clients will go through a tailored “strengths-assessment” that assists the client in establishing goals, generating resource options and opportunities, setting short-term goals and tasks, and directing roles and responsibilities [52]. In cardiac rehabilitation and exercise settings, it is not uncommon for practitioners to make use of different strengths-based approaches to support clients in enhancing their health and wellbeing [16].

- Relationship is Hope-Inducing: Strengths-based approaches are designed to enhance the hopefulness of the client. Hope can be realized by finding strengths and through empowering relationships with others, communities, and/or culture. This process allows clients to increase their perceptions regarding their abilities, enhance clients’ options and perceptions of these options, and increase the confidence and opportunities of clients to choose and act on these choices [52]. In physical activity promotion, identifying strengths related to physical activity participation and connecting with other people, communities, and culture can build hope towards enhancing health and wellbeing [48].

- Meaningful Choice: Central to a strengths-based approach is the belief that clients are the experts in their own lives. The practitioner’s role is to enhance and explain choices, encouraging clients to make their own informed decisions and choices [51,52]. Through a strengths-based approach in physical activity promotion, we can support self-empowerment and self-determination wherein clients have control over their health and wellbeing. By being active participants in their own health and wellbeing, there are also greater learning opportunities for clients, such as facilitating a greater understanding of the importance of routine physical activity participation for health and wellness.

4. Conclusions

5. Key Take-Home Message

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Lost in Translation: What does the physical activity and health evidence actually tell us? In Lifestyle in Heart Health and Disease; Zibadi, S., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Taunton, J.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Isserow, S. The risk-benefit paradox of exercise. BC Med. J. 2016, 58, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, D.E.; Bredin, S.S. Reflections on Physical Activity and Health: What Should We Recommend? Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.; Bredin, S.S. Prescribing exercise as preventive therapy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 174, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Warburton, D.E.; Janssen, I.; Paterson, D.H.; Latimer, A.E.; Rhodes, R.E.; Kho, M.E.; Hicks, A.; Leblanc, A.G.; Zehr, L.; et al. New canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 118.

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- UK Chief Medical Officers. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines; UK Chief Medical Officers: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, A.; Abu-Omar, K.; Messing, S.; Weege, M.; Pfeifer, K.; Geidl, W.; Hartung, V. How can the impact of national recommendations for physical activity be increased? Experiences from Germany. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlmeier, S.; Wijnhoven, T.M.; Alpiger, P.; Schweizer, C.; Breda, J.; Martin, B.W. National physical activity recommendations: Systematic overview and analysis of the situation in European countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomantonio, N.B.; Bredin, S.S.; Foulds, H.J.; Warburton, D.E. A systematic review of the health benefits of exercise rehabilitation in persons living with atrial fibrillation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2013, 29, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.A.; Buckley, J.P.; Warburton, D.E.R.; Sanderson, B.; Grace, S.L. International Charter on Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation: A Call for Action. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2013, 33, 128–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tone, J.A. Canadian Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Translating Knowledge into Action, 3rd ed.; Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Rhodes, R.E.; Shephard, R.J. Evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for Canadian adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, S16–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Charlesworth, S.; Ivey, A.; Nettlefold, L.; Bredin, S.S. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, D.H.; Warburton, D.E. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: A systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Jamnik, V.; Shephard, R.J.; Gledhill, N. Consensus on Evidence-Based Preparticipation Screening and Risk Stratification. In Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 53–102. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.; McAuley, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Despres, J.P.; Arena, R.; Kokkinos, P. Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as major markers of cardiovascular risk: Their independent and interwoven importance to health status. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menai, M.; van Hees, V.T.; Elbaz, A.; Kivimaki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Sabia, S. Accelerometer assessed moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and successful ageing: Results from the Whitehall II study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arem, H.; Moore, S.C.; Patel, A.; Hartge, P.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Visvanathan, K.; Campbell, P.T.; Freedman, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.O.; et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: A detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.B.; Overland, S.; Hatch, S.L.; Wessely, S.; Mykletun, A.; Hotopf, M. Exercise and the Prevention of Depression: Results of the HUNT Cohort Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedisic, Z.; Shrestha, N.; Kovalchik, S.; Stamatakis, E.; Liangruenrom, N.; Jozo Grgic, J.; Titze, S.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Bauman, A.E.; Oja, P. Is running associated with a lower risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and is the more the better? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Tarp, J.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.H.; Jefferis, B.; Fagerland, M.W.; Whincup, P.; Diaz, K.M.; Hooker, S.P.; Chernofsky, A.; et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: Systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.R. (Ed.) The health benefits of physical activity: A brief review. In Health-related Exercise Prescription for the Qualified Exercise Professional, 6th ed.; Health & Fitness Society of BC: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, C.; Shephard, R.J. Physical activity fitness and health: The model and key concepts. In Physical Activity Fitness and Health: International Proceedings and Consensus Statement; Bouchard, C., Shephard, R.J., Stephens, T., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, D.E.; Gledhill, N.; Quinney, A. Musculoskeletal fitness and health. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 26, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattelmair, J.; Pertman, J.; Ding, E.L.; Kohl, H.W., III; Haskell, W.; Lee, I.M. Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Circulation 2011, 124, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredin, S.S.; Warburton, D.E. Physical Activity Line: Effective knowledge translation of evidence-based best practice in the real-world setting. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can. 2013, 59, 967–968. [Google Scholar]

- Bredin, S.S.; Gledhill, N.; Jamnik, V.K.; Warburton, D.E. PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+: New risk stratification and physical activity clearance strategy for physicians and patients alike. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can. 2013, 59, 273–277. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, E.C.; Webb, O.J.; Esliger, D.W.; Biddle, S.J.; Sherar, L.B. Using threshold messages to promote physical activity: Implications for public perceptions of health effects. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L. Will today’s children die earlier than their parents? BBC News. 8 July 2014. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28191865 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Preston, S.H.; Stokes, A.; Mehta, N.K.; Cao, B. Projecting the effect of changes in smoking and obesity on future life expectancy in the United States. Demography 2014, 51, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, L.P.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Orr, K.; Berry, T.; Deshpande, S.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; O’Reilly, N.; Rhodes, R.E.; Tremblay, M.S.; Faulkner, G. Canadian physical activity guidelines for adults: Are Canadians aware? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G.G.; Wolin, K.Y.; Puleo, E.M.; Masse, L.C.; Atienza, A.A. Awareness of national physical activity recommendations for health promotion among US adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, N.M.; Nolan, R.; Dollman, J. Associations of awareness of physical activity recommendations for health and self-reported physical activity behaviours among adult South Australians. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, J.A.; Shaw, M. Questionnaire survey assessing the leisure-time physical activity of hospital doctors and awareness of UK physical activity recommendations. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainforth, H.L.; Berry, T.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Tremblay, M.S.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Evaluating the uptake of Canada’s new physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines on service organizations’ websites. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013, 3, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segar, M.L.; Guerin, E.; Phillips, E.; Fortier, M. From a Vital Sign to Vitality: Selling Exercise So Patients Want to Buy It. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2016, 15, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Fiala, B. Building motivation and sustainability into the prescription and recommendations for physical activity and exercise therapy: The evidence. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2009, 25, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Fiala, B.; Conner, M. A review and meta-analysis of affective judgments and physical activity in adult populations. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 38, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Quinlan, A. Predictors of physical activity change among adults using observational designs. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirkovic, J.; Kristjansdottir, O.B.; Stenberg, U.; Krogseth, T.; Stange, K.C.; Ruland, C.M. Patient Insights Into the Design of Technology to Support a Strengths-Based Approach to Health Care. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H. Strengths-based approach for mental health recovery. Iran. J Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2013, 7, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, S.; Stanley, T.; Colomina, C.; Pereira, T. Strengths-Based Approach: Practice Framework and Practice Handbook; Department of Health & Social Care: London, UK, 2019; p. 105. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/strengths-based-social-work-practice-framework-and-handbook (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Lai, H.P.H.; Miles, R.M.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Kaufman, K.L.; Chua, C.Z.Y.; Hare, J.; Norman, M.E.; Rhodes, R.E.; Oh, P.; Warburton, D.E.R. “With Every Step, We Grow Stronger”: The Cardiometabolic Benefits of an Indigenous-Led and Community-Based Healthy Lifestyle Intervention. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Crockett, J.; Dudgeon, P.; Bernoth, M.; Lincoln, M. Sharing and valuing older Aboriginal people’s voices about social and emotional wellbeing services: A strength-based approach for service providers. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Franklin, C.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Park, S.; Kim, J. The effectiveness of strength-based, solution-focused brief therapy in medical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattoni, L. Strengths-Based Approaches for Working with Individuals; Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services, Ed.; Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services: Glasgow, Scotland, 1 May 2012; Available online: https://www.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/iriss-insight-16.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Rapp, C.A.; Saleebey, D.; Sullivan, W.P. The future of strengths-based social work. Arch. Soc. Work 2005, 6, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 27 June 2019. Available online: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Tse, S.; Ng, S.M.C.; Yuen, W.Y.W.; Fukui, S.; Goscha, R.J.; Lo, W.K.I. Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of strengths model case management (SMCM) with Chinese mental health service users in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuglin Jones, A. Oncology Nurse Retreat: A Strength-Based Approach to Self-Care and Personal Resilience. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 21, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, G. Finding a voice through ‘The Tree of Life’: A strength-based approach to mental health for refugee children and families in schools. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verney, S.P.; Avila, M.; Espinosa, P.R.; Cholka, C.B.; Benson, J.G.; Baloo, A.; Pozernick, C.D. Culturally sensitive assessments as a strength-based approach to wellness in Native communities: A community-based participatory research project. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingey, L.; Larzelere-Hinton, F.; Goklish, N.; Ingalls, A.; Craft, T.; Sprengeler, F.; McGuire, C.; Barlow, A. Entrepreneurship education: A strength-based approach to substance use and suicide prevention for American Indian adolescents. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, N.; Dalton, H.; Perkins, D.; Considine, R.; Hughes, S.; Osborne, S.; Buss, R. Our Healthy Clarence: A Community-Driven Wellbeing Initiative. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tsoi, E.W.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Shepherd, G.; Slade, M.; Whitley, R.; Petrakis, M. Uses of strength-based interventions for people with serious mental illness: A critical review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2016, 62, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredin, S.S.D.; Warburton, D.E.R.; Lang, D.J. The health benefits and challenges of exercise training in persons living with schizophrenia: A pilot study. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 821–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabboul, N.N.; Tomlinson, G.; Francis, T.A.; Grace, S.L.; Chaves, G.; Rac, V.; Daou-Kabboul, T.; Bielecki, J.M.; Alter, D.A.; Krahn, M. Comparative Effectiveness of the Core Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Mortality and Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rountree, J.; Smith, A. Strength-based well-being indicators for Indigenous children and families: A literature review of Indigenous communities’ identified well-being indicators. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interior Health. Aboriginal Health & Wellness Strategy, 2015–2019; Interior Health: Kelowna, BC, Canada, 2015; Available online: https://www.interiorhealth.ca/YourHealth/AboriginalHealth/Documents/AboriginalHealthStrategy.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- First Nations Health Authority. Traditional Wellness Strategic Framework; First Nations Health Authority: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council on Learning. State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success; Canadian Council on Learning: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds, H.J.A.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Warburton, D.E.R. Ethnic differences in vascular function and factors contributing to blood pressure. Can. J. Public Health 2018, 109, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Aboriginal Health Organization. Cultural Competency and Safety in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Care; National Aboriginal Health Organization: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.; Tsourtos, G.; Lawn, S. The barriers and facilitators that indigenous health workers experience in their workplace and communities in providing self-management support: A multiple case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, H.J.; Bredin, S.S.; Warburton, D.E. The effectiveness of community based physical activity interventions with Aboriginal peoples. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, G. Seven Principles for a Strengths-based Approach to Working with Groups; Family Action Centre, University of Newcastle, 23 August 2016; Available online: https://sustainingcommunity.wordpress.com/2016/08/23/sba-groups/ (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Hare, J. Learning From Story; edX Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.edx.org/course/reconciliation-through-indigenous-education (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Smith, L.T. (Ed.) Twenty-five Indigenous projects. In Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; University of Otago Press: Dunedin, New Zealand, 1999; pp. 144–145. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, J.-A. (Ed.) Learning about storywork from Stó:lō Elders. In Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action; Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2015; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Goforth, S. Aboriginal healing methods for residential school abuse and intergenerational effects: A review of the literature. J. Nativ. Soc. Work 2007, 6, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, D.E.R. Special Issue “Cardiac Rehabilitation”. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/jcm/special_issues/Cardiac_Rehab (accessed on 1 November 2019).

| Weaknesses (Deficits-based) | Strengths |

|---|---|

| Instead of These Weakness Statements… | …Try These Strength Statements |

| Population-based Messaging | |

| Adults should engage in at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity on a weekly basis. | We are excited about the potential for small changes in physical activity to lead to marked health and wellness benefits, particularly in inactive individuals. Simply by moving more, we can improve the health and wellbeing of society. |

| Our children today will die at a younger age than their parents. | We have a great opportunity to address challenges such as obesity to enhance the health and wellbeing of our children through physical activity and other healthy lifestyle behaviors. |

| Children and adults have received a failing grade with respect to physical activity. | Many children and adults are active and reaping the benefits of routine physical activity. Building on the inherent strengths and resources available to children and adults, we can work together to meet the goal of being healthier and feeling better. |

| If you are inactive or sedentary your chances of dying prematurely rise markedly. | By moving more and sitting less, we can achieve the goal of a healthier society. |

| Person-centered Messaging | |

| Like the majority of Canadians, I am physically inactive and therefore do not get all of the benefits associated with physical activity. | I look forward to building on my strengths, to become more active so that I can achieve the health and wellness benefits associated with physical activity. |

| I live with a chronic medical condition and am fearful of engaging in exercise. | I am happy to hear that physical activity is of benefit and quite safe for virtually everyone, including people living with chronic medical conditions. |

| I have been told that in order to achieve health benefits, I must engage in at least 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on a weekly basis. | I am excited to know that small changes in physical activity levels can lead to significant health benefits. By making small changes in my activities, I can meet my goal to be happier and healthier. |

| I do so little physical activity daily that it is hard to imagine that I could meet international recommendations. | I realize that I do not need to engage in large amounts of physical activity to take control over my health and wellbeing. |

| My lifestyle habits and patterns have made me weak and susceptible to dying early and developing several chronic medical conditions. | I will build upon my strengths and the support of my family to be healthier. If I make small changes, one at a time, I will surprise myself by how much I can achieve. |

| I find many physical activities not enjoyable. | I will focus on physical activities that are enjoyable, so I can experience the multiple benefits of being physical active. |

| I do not enjoy exercising on my own. | My family and friends are excited to help me on my journey to become more physically active. |

| In the past, I have doubted myself about my ability to become more physically active on a routine basis. | I have a strong conviction to be more active and healthier. I am excited about my potential to be more active and healthier for years to come. |

| I do not feel confident about my ability to be physically active. | Looking at my inherent strengths and the support of my family and community, I feel empowered to become more physically active. |

| I feel helpless and do not know what to do. | Building on my strengths and available support systems, I can have greater control over my health and wellbeing. I have a strong sense of hope and optimism for my future. |

| I do not have enough time. | I can take the limited time that I have available to make small changes in my activity patterns. |

| When working with exercise professionals in the past, I have had little control over my activity programming. | By working together with exercise professionals, we can discuss my aspirations so that I am empowered to be more active and healthier. |

| I do not have a good understanding of the best way of becoming more physically active. | I look forward to working with experts and other members from my family or community on exploring the best ways to become more active and healthier. |

| I do not know of all of the opportunities available to me in my community. | Working together with my family, others from my community, and/or practitioners, I can gain a greater understanding of the physical activity resources that are available to me within my own community. |

| I cannot afford the costs associated with being physically active. | I am excited to engage in free activities that can be done within my own community with my family and friends. |

| I am fearful of the challenges associated with exercising with others. | I am hopeful of the strengthened relationships that I can develop through physical activity with my family and community. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Strengths-Based Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122044

Warburton DER, Bredin SSD. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Strengths-Based Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(12):2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122044

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarburton, Darren E. R., and Shannon S. D. Bredin. 2019. "Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Strengths-Based Approach" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 12: 2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122044

APA StyleWarburton, D. E. R., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2019). Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Strengths-Based Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(12), 2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122044