Manualised Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: Use of Treatment Modules in the ANTOP Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What were the most commonly used modules?

- What were the most commonly used worksheets?

- Was there a relationship between stage of therapy and module used?

- Was there a relationship between duration of illness and module used?

2. Methods

2.1. CBT-E in the ANTOP Study

2.2. Sample

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

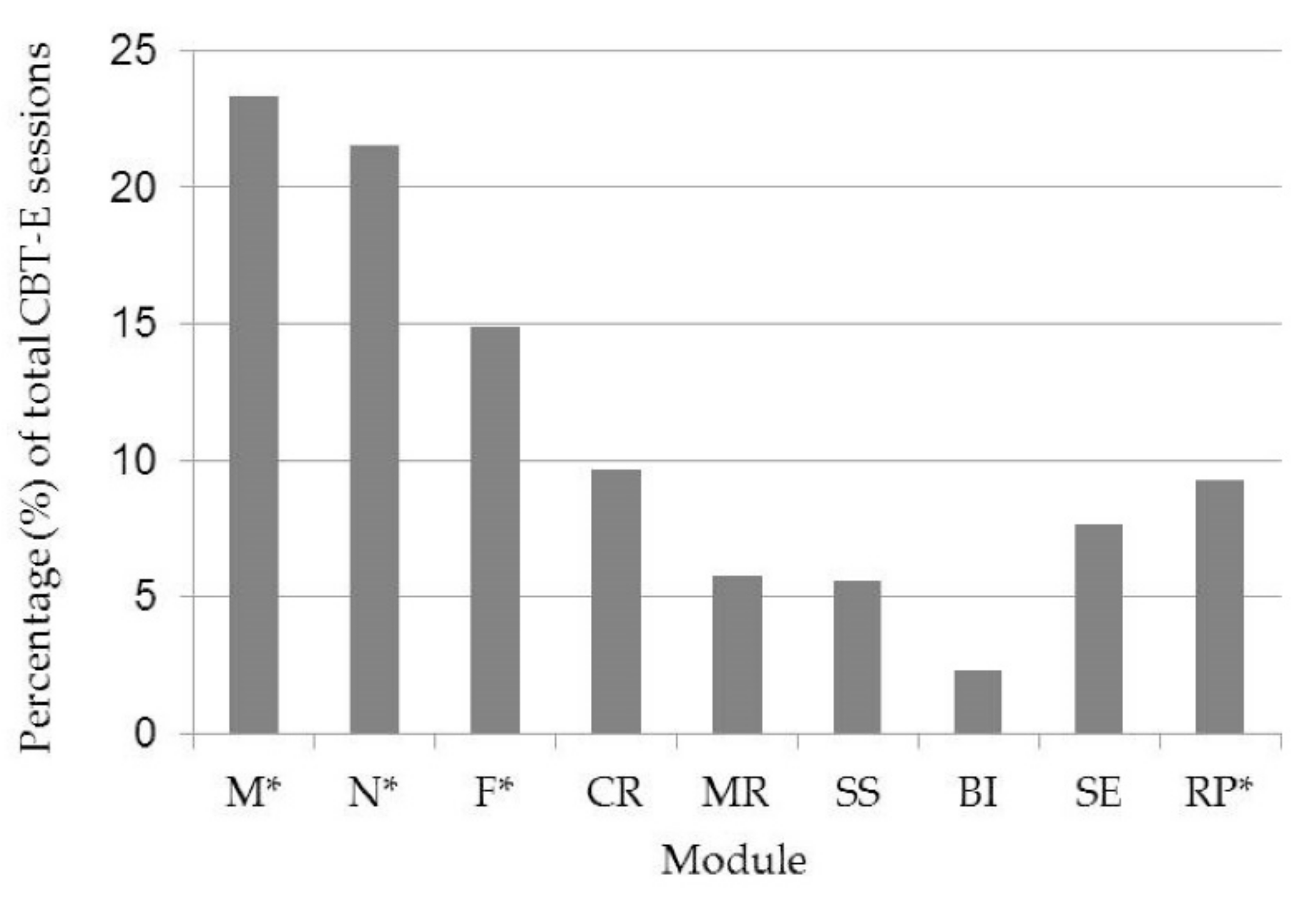

3.1. Modules

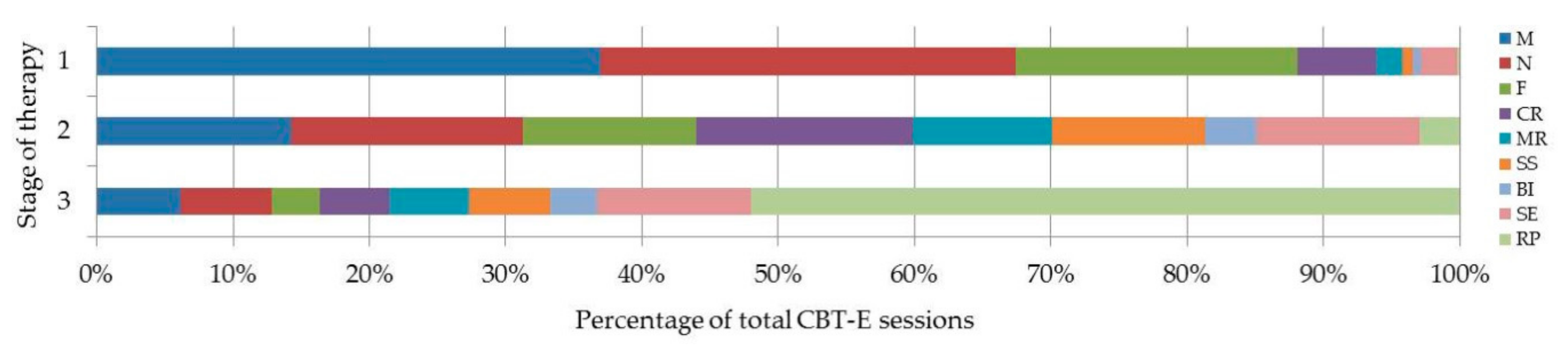

3.2. Relationship between Module and Stage of Therapy

3.3. Relationship between Module and Duration of Illness

3.4. Worksheets

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lang, P. Einstellung von Psychotherapeuten zu Therapieleitlinien und Manualisierter Therapie bei Anorexia Nervosa und Bulimia Nervosa. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Ulm, Ulm, Gremany, 2010. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M.; Cardemil, E.; Duncan, B.; Miller, S. Does Manualization Improve Therapy Outcomes? In Evidence-Based Practices in Mental Health: Debate and Dialogue on the Fundamental Questions; Norcross, J., Beutler, L., Levant, R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 131–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Legenbauer, T.; Vocks, S. Manual der kognitiven Verhaltenstherapie bei Anorexie und Bulimie; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, S.; Phillips, K.; Steketee, G. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Treatment Manual; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Z.; Doll, H.; Hawker, D. Testing a new cognitive behavioral treatment for obesity: A randomized controlled trial with three-year follow-up. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z.; Doll, H.A.; O’Connor, M.E.; Bohn, K.; Hawker, D.M.; Wales, J.A.; Palmer, R.L. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am. J. Psychiatry 2009, 166, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, S.; Phillips, K.; Didie, E. Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Calugi, S.; Conti, M. Inpatient cognitive behavior therapy for anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013, 82, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knott, S.; Woodward, D.; Hoefkens, A.; Limbert, C. Cognitive behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified: Translation from randomized controlled trial to clinical setting. Behav. Cognit. Psychother. 2015, 43, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, S.; Wade, T.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S.; Fairburn, C.; Treasure, J.; Schmidt, U.; McIntosh, V.; Allen, K.; Fursland, A.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of three psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2823–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeck, A.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Friederich, H.-C.; Brockmeyer, T.; Resmark, G.; Hagenah, U.; Ehrlich, S.; Cuntz, U.; Zipfel, S.; Hartmann, A. Psychotherapeutic treatment for anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.; Hawker, D. Cognitive–Behavioral Treatment of Obesity: A Clinician’s Guide; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rießen, I.; Zipfel, S.; Groß, G. Ambulante manualisierte Verhaltenstherapie bei Anorexia nervosa—Erfahrungsbericht aus der Supervision. Psychotherapeut 2010, 55, 496–502. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, B.; Friederich, H.-C.; Gross, G.; Teufel, M.; Herzog, W.; Giel, K.E.; de Zwaan, M.; Schauenburg, H.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Schäfer, H.; et al. The ANTOP study: Focal psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioural therapy, and treatment-as-usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa—A randomized controlled trial. Trials 2009, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, S.; Wild, B.; Friederich, H.-C.; Teufel, M.; Schellberg, D.; Giel, K.E.; de Zwaan, M.; Dinkel, A.; Herpertz, S.; Burgmer, M.; et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): Randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, T.; Schumacker, R. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J. Exp. Educ. 1995, 64, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, K.; Watson, S.; Wilson, G. Enhancing motivation for change in treatment-resistant eating disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 18, 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagmar, O.; Aebi, M.; Winkler Metzke, C.; Steinhausen, H.-C. Motivation to change, coping, and self-esteem in adolescent anorexia nervosa: A validation study of the Anorexia Nervosa Stages of Change Questionnaire. J. Eat Disord. 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, Q. Motivation in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review of Theoretical and Empirical Literature; Pepperdine University: California, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yager, J.; Devlin, M.; Halmi, K.; Herzog, D.; Mitchell, J.; Powers, P.; Zerbe, K. Treatment of patients with eating disorders, third edition. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 4–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch, H. Anorexia nervosa: Therapy and theory. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzola, E.; Nasser, J.; Hashim, S. Nutritional rehabilitation in anorexia nervosa: Review of the literature and implications for treatment. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; Amiaz, R.; Davidson, N.; Czerniak, E.; Gur, E.; Kiryati, N.; Harari, D.; Furst, M.; Stein, D. Computerized assessment of body image in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Comparison with standardized body image assessment tool. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2017, 20, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delinsky, S. Body Image and Anorexia Nervosa; Cash, T., Smolak, L., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Junne, F.; Zipfel, S.; Wild, B.; Martus, P.; Giel, K.; Resmark, G.; Friederich, H.-C.; Teufel, M.; de Zwaan, M.; Dinkel, A.; et al. The relationship of body image with symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with anorexia nervosa during outpatient psychotherapy: Results of the ANTOP study. Psychotherapy 2016, 53, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.; Bulik, C. Anorexia nervosa: Aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junne, F.; Wild, B.; Resmark, G.; Giel, K.E.; Teufel, M.; Martus, P.; Ziser, K.; Friederich, H.-C.; de Zwaan, M.; Löwe, B.; et al. The importance of body image disturbances for the outcome of outpatient psychotherapy in patients with anorexia nervosa: Results of the ANTOP-study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco, J.; Perpina, C.; Botella, C. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy supported by virtual reality in the treatment of body image in eating disorders: One year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 209, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, K.; Carter, J.; Olmsted, M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa. In the Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Clinical Handbook; Grilo, C., Mitchell, J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen, H.-C. The outcomes of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, L.; Rhodes, P.; Touyz, S. The recovery model and anorexia nervosa. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touyz, S.; Le Grange, D.; Lacey, J.; Hay, P. Managing Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: A Clinician’s Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Module | Module Content |

|---|---|

| Compulsory Modules | |

| Motivation (Starting Well) | Building a therapeutic relationship, reflecting on pros and cons of anorexia nervosa (AN), and discussing healthy eating behaviours |

| Nutrition | Establishing and maintaining a regular healthy eating pattern |

| Formulation | Understanding what causes and maintains the individual’s eating disorder |

| Relapse Prevention (Ending Well) | Maintaining positive behavioural changes learnt throughout the course of therapy and preparing to cope with setbacks |

| Optional Modules | |

| Cognitive Restructuring | Learning to challenge dysfunctional beliefs concerning eating, weight and the body |

| Mood Regulation | Recognising and coping with negative emotions |

| Social Skills | Improving communication and conflict resolutions skills |

| Body Image | Addressing the negative attitudes towards patients’ own bodies, and the influence of perceived figure/weight on self-worth |

| Self Esteem and Resources | Increasing self-worth: Identifying strengths, establishing new hobbies and interests, reflecting on what brings happiness |

| Name of Worksheet (Module) | Number of Times Distributed (%) |

|---|---|

| The Scales (Motivation) | 107 (12) |

| Family relationships (Formulation) | 56 (6.3) |

| Two letters to the eating disorder (Motivation) | 53 (6.0) |

| How I’d like to change my eating behaviour (Nutrition) | 43 (4.8) |

| Cognitive distortions (Cognitive Restructuring) | 37 (4.2) |

| What have I learnt (Formulation) | 34 (3.8) |

| Analysis of a monitoring record (Nutrition) | 29 (3.3) |

| Paths to change (Nutrition) | 27 (3.0) |

| Toolbox for emergencies (Relapse Prevention) | 26 (2.9) |

| What I need to be content (Self Esteem) | 26 (2.9) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Resmark, G.; Kennedy, B.; Mayer, M.; Giel, K.; Junne, F.; Teufel, M.; De Zwaan, M.; Zipfel, S. Manualised Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: Use of Treatment Modules in the ANTOP Study. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110398

Resmark G, Kennedy B, Mayer M, Giel K, Junne F, Teufel M, De Zwaan M, Zipfel S. Manualised Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: Use of Treatment Modules in the ANTOP Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2018; 7(11):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110398

Chicago/Turabian StyleResmark, Gaby, Brigid Kennedy, Maria Mayer, Katrin Giel, Florian Junne, Martin Teufel, Martina De Zwaan, and Stephan Zipfel. 2018. "Manualised Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: Use of Treatment Modules in the ANTOP Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 7, no. 11: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110398

APA StyleResmark, G., Kennedy, B., Mayer, M., Giel, K., Junne, F., Teufel, M., De Zwaan, M., & Zipfel, S. (2018). Manualised Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: Use of Treatment Modules in the ANTOP Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(11), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110398