Enhanced Imaging of Ocular Surface Lesions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

2.1. Background

2.2. Current Applications of AS-OCT

2.3. Advantages and Disadvantages

2.4. Recent Advances

2.5. Summary

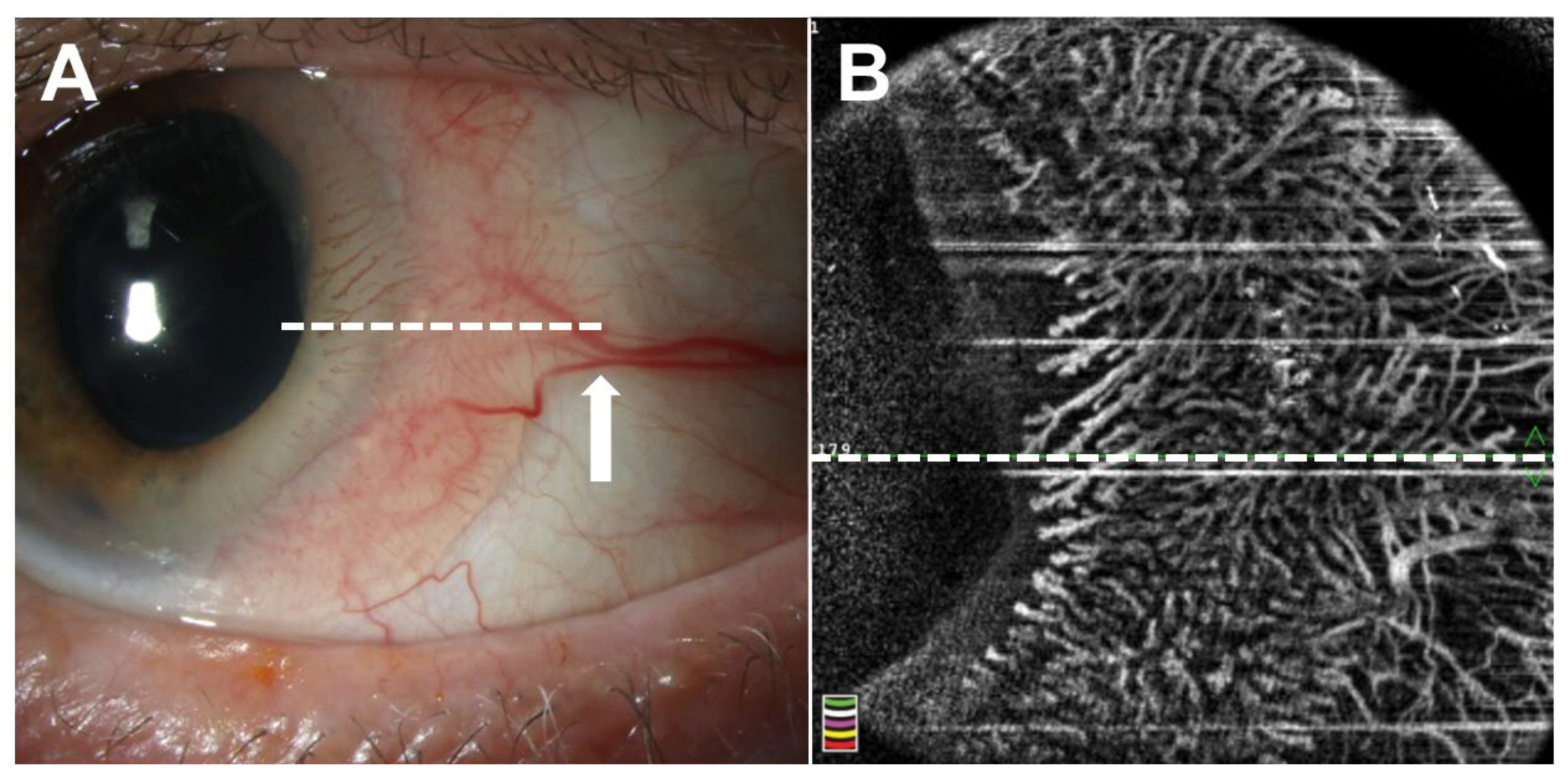

3. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography

3.1. Background

3.2. Current Applications of OCTA

3.3. Advantages and Disadvantages

3.4. Recent Advances

3.5. Summary

4. Ultrasound Biomicroscopy

4.1. Background

4.2. Current Applications of UBM

4.3. Advantages and Disadvantages

4.4. Recent Advances

4.5. Summary

5. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy

5.1. Background

5.2. Current Applications of IVCM

5.3. Advantages and Disadvantages

5.4. Recent Advances

5.5. Summary

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nanji, A.A.; Mercado, C.; Galor, A.; Dubovy, S.; Karp, C.L. Updates in Ocular Surface Tumor Diagnostics. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2017, 57, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, M.; Baskaran, M.; Werkmeister, R.M.; Chua, J.; Schmidl, D.; Aranha Dos Santos, V.; Garhofer, G.; Mehta, J.S.; Schmetterer, L. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 66, 132–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzayev, I.; Gunduz, A.K.; Aydin Ellialtioglu, P.; Gunduz, O.O. Clinical applications of anterior segment swept-source optical coherence tomography: A systematic review. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 42, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitgeb, R.; Hitzenberger, C.; Fercher, A. Performance of fourier domain vs. time domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2003, 11, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkateswaran, N.; Mercado, C.; Wall, S.C.; Galor, A.; Wang, J.; Karp, C.L. High resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography of ocular surface lesions: A review and handbook. Expert. Rev. Ophthalmol. 2021, 16, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhi, M.; Liu, J.J.; Qavi, A.H.; Grulkowski, I.; Lu, C.D.; Mohler, K.J.; Ferrara, D.; Kraus, M.F.; Baumal, C.R.; Witkin, A.J.; et al. Choroidal analysis in healthy eyes using swept-source optical coherence tomography compared to spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 1272–1281.E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, A.K.; Mirzayev, I.; Okcu Heper, A.; Kuzu, I.; Gahramanli, Z.; Cansiz Ersoz, C.; Gunduz, O.O.; Ataoglu, O. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography in ocular surface tumours and simulating lesions. Eye 2023, 37, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskowitz, W.R.; De Arrigunaga, S.; Greenfield, J.A.; Cohen, N.K.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Can high-resolution optical coherence tomography provide an optical biopsy for ocular surface lesions? Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 60, e185–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanji, A.A.; Sayyad, F.E.; Galor, A.; Dubovy, S.; Karp, C.L. High-Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography as an Adjunctive Tool in the Diagnosis of Corneal and Conjunctival Pathology. Ocul. Surf. 2015, 13, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, H.; Chan, E. Optical coherence tomography imaging in keratoconus. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, A.A.; D’Oria, F.; Alio Del Barrio, J.; Alio, J.L. The Value of Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography in Different Types of Corneal Infections: An Update. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.; Sah, R.K.; Bhandari, G.; Bhandari, S.; Byanju, R.; Kandel, R.P.; Thompson, I.J.B.; Stevens, V.M.; Aromin, K.M.; Oatts, J.T.; et al. Anterior Segment OCT for Detection of Narrow Angles: A Community-Based Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2024, 7, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theotoka, D.; Wall, S.; Galor, A.; Sripawadkul, W.; Khzam, R.A.; Tang, V.; Sander, D.L.; Karp, C.L. The use of high resolution optical coherence tomography (HR-OCT) in the diagnosis of ocular surface masqueraders. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 24, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modabber, M.; Lent-Schochet, D.; Li, J.Y.; Kim, E. Histopathological Rate of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia in Clinically Suspected Pterygium Specimens: 10-Year Results. Cornea 2022, 41, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellers, P.; Karp, C.L.; Sheth, A.; Kao, A.A.; Abdelaziz, A.; Matthews, J.L.; Dubovy, S.R.; Galor, A. Prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of coexistent ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygium. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, L.F.; Zapata, M.; Gil, J.C. An Unexpected Incidence of Ocular Surface Neoplasia on Pterygium Surgery. A Retrospective Clinical and Histopathological Report. Cornea 2021, 40, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Garcia, I.; Romero Caballero, M.D.; Selles Navarro, I. High resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography for differential diagnosis between corneo-conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia and pterygium. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2020, 95, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieval, J.Z.; Karp, C.L.; Abou Shousha, M.; Galor, A.; Hoffman, R.A.; Dubovy, S.R.; Wang, J. Ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography for differentiation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygia. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskan, C.; Kilicarslan, A. How Can We Diagnose Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia with Optical Coherence Tomography? Cureus 2023, 15, e36320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripawadkul, W.; Khzam, R.A.; Tang, V.; Zein, M.; Dubovy, S.R.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography characteristics of conjunctival papilloma as compared to papilliform ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Eye 2023, 37, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, A.K.; Mirzayev, I.; Ersoz, C.C.; Heper, A.O.; Gunduz, O.; Ozalp Ates, F.S. Anterior Segment Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography in Ocular Surface Tumors and Simulating Lesions and Correlation with Histopathologic Diagnosis. Cornea 2025, 44, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, Y.A.; Kumar, S.; Abdul Aziz, H.; Plesec, T.; Singh, A.D. Primary Acquired Melanosis: Clinical, Histopathologic and Optical Coherence Tomographic Correlation. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2016, 2, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, C.L.; Belinsky, I.; Romanelli-Gobbi, M.; Guzman, J.M.; Mazzuca, D., Jr.; Green, W.R.; Bianciotto, C.; Shields, J.A. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography of conjunctival nevus. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, N.; Mercado, C.; Tran, A.Q.; Garcia, A.; Diaz, P.F.M.; Dubovy, S.R.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. The use of high resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography for the characterization of conjunctival lymphoma, conjunctival amyloidosis and benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Eye Vis. 2019, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Villacorta, R.; Davila-Alquisiras, J.H.; Ramos-Betancourt, N.; Vazquez-Romo, K.A.; Hernandez-Ayuso, I.; Rios, Y.V.-V.D.; Rodriguez-Reyes, A.A. Conjunctival Myxoma: High-Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography Findings of a Rare Tumor. Cornea 2022, 41, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.W.; Herskowitz, W.R.; Tang, V.; Khzam, R.A.; Dubovy, S.R.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Characteristics of conjunctival myxomas on anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 59, e865–e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Okafor, K.C.; Cavuoto, K.M.; Dubovy, S.R.; Karp, C.L. Pediatric Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2B: Clinicopathological Correlation of Perilimbal Mucosal Neuromas and Treatment of Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2018, 4, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzayev, I.; Gunduz, A.K.; Cansiz Ersoz, C.; Gunduz, O.O.; Gahramanli, Z. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography, in vivo confocal microscopy, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical findings in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020, 41, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, Y.; Nangia, P.; Ahmad, H.; Frauches, R.L.; Lin, J.H.; Mruthyunjaya, P. Conjunctival blue nevus in a child-Case report and review of literature. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2024, 36, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboumourad, R.J.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Case Series: High-resolution Optical Coherence Tomography as an Optical Biopsy in Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2021, 98, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shousha, M.A.; Karp, C.L.; Canto, A.P.; Hodson, K.; Oellers, P.; Kao, A.A.; Bielory, B.; Matthews, J.; Dubovy, S.R.; Perez, V.L.; et al. Diagnosis of ocular surface lesions using ultra-high-resolution optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B.J.; Galor, A.; Nanji, A.A.; El Sayyad, F.; Wang, J.; Dubovy, S.R.; Joag, M.G.; Karp, C.L. Ultra high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul. Surf. 2014, 12, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Farhan, M.H.; Mishra, D.K.; Kaliki, S. Corneal ocular surface squamous neoplasia: Case series and review of literature. Oman J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 17, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.J.; Locatelli, E.V.T.; Huang, J.J.; De Arrigunaga, S.; Rao, P.; Dubovy, S.; Karp, C.L.; Galor, A. It Is All About the Angle: A Clinical and Optical Coherence Tomography Comparison of Corneal Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia and Corneal Pannus. Cornea 2024, 43, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Arrigunaga, S.; Wall, S.; Theotoka, D.; Friehmann, A.; Camacho, M.; Dubovy, S.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Chronic inflammation as a proposed risk factor for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul. Surf. 2024, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, M.; Joag, M.; Galor, A.; Amescua, G.; Nanji, A.; Wang, J.; Perez, V.L.; Dubovy, S.; Karp, C.L. Role of high resolution optical coherence tomography in diagnosing ocular surface squamous neoplasia with coexisting ocular surface diseases. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vempuluru, V.S.; Sinha, P.; Gavara, S.; Jakati, S.; Luthra, A.; Kaliki, S. Clinico-tomographic-pathological correlation in nodulo-ulcerative ocular surface squamous neoplasia: A study of 16 cases. Int. Ophthalmol. 2025, 45, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangahas, L.J.; Reyes, R.W.; Siazon, R. Primary Conjunctival Basal Cell Carcinoma Mimicking an Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia in a Young Adult Filipino: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2024, 2024, 3113342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, N.; Galor, A.; Wang, J.; Karp, C.L. Optical coherence tomography for ocular surface and corneal diseases: A review. Eye Vis. 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, N.; Sripawadkul, W.; Karp, C.L. The role of imaging technologies for ocular surface tumors. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 32, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.R.; Nanji, A.A.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Management of conjunctival malignant melanoma: A review and update. Expert. Rev. Ophthalmol. 2014, 9, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.A.; Shields, C.L.; Mashayekhi, A.; Marr, B.P.; Benavides, R.; Thangappan, A.; Phan, L.; Eagle, R.C., Jr. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva: Risks for progression to melanoma in 311 eyes. The 2006 Lorenz E. Zimmerman lecture. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 511–519.E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levecq, L.; De Potter, P.; Jamart, J. Conjunctival nevi clinical features and therapeutic outcomes. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenworthy, M.K.; Kenworthy, S.J.; De Guzman, P.; Morlet, N. Conjunctival amelanotic melanoma presenting as a multifocal pink lesion. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e250682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliki, S.; Vempuluru, V.S.; Ghose, N.; Gunda, S.; Vithalani, N.M.; Sultana, S.; Ganguly, A.; Bejjanki, K.M.; Jakati, S.; Mishra, D.K. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia in India: A study of 438 patients. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.Q.; Venkateswaran, N.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Utility of high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of sub-clinical ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Eye Vis. 2019, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.; Galor, A.; Nanji, A.; Joag, M.; Palioura, S.; Feuer, W.; Karp, C.L. Ability of novice clinicians to interpret high-resolution optical coherence tomography for ocular surface lesions. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 53, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizvari, E.; Skribek, A.; Polgar, N.; Voros, A.; Sziklai, P.; Toth-Molnar, E. Conjunctival melanocytic naevus: Diagnostic value of anterior segment optical coherence tomography and ultrasound biomicroscopy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianciotto, C.; Shields, C.L.; Guzman, J.M.; Romanelli-Gobbi, M.; Mazzuca, D., Jr.; Green, W.R.; Shields, J.A. Assessment of anterior segment tumors with ultrasound biomicroscopy versus anterior segment optical coherence tomography in 200 cases. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, K.; Mertens, M.; Lauwers, N.; de Keizer, R.J.; Mathysen, D.G.; De Groot, V. To Study and Determine the Role of Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography and Ultrasound Biomicroscopy in Corneal and Conjunctival Tumors. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016, 1048760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevenne, M.M.; Favuzza, E.; Veta, M.; Lucenteforte, E.; Berendschot, T.T.; Mencucci, R.; Nuijts, R.M.; Virgili, G.; Dickman, M.M. Artificial intelligence for detecting keratoconus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 11, CD014911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Baskaran, M.; Xu, Y.; Lin, S.; Wong, D.W.K.; Liu, J.; Tun, T.A.; Mahesh, M.; Perera, S.A.; Aung, T. A Deep Learning System for Automated Angle-Closure Detection in Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography Images. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 203, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, J.A.; Scherer, R.; Alba, D.; De Arrigunaga, S.; Alvarez, O.; Palioura, S.; Nanji, A.; Bayyat, G.A.; da Costa, D.R.; Herskowitz, W.; et al. Detection of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia Using Artificial Intelligence with Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 273, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, M.; Shi, C.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Pu, J.; Chen, H. EE-Net: An edge-enhanced deep learning network for jointly identifying corneal micro-layers from optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Signal Process Control 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Mathai, T.S.; Lathrop, K.; Galeotti, J. Accurate tissue interface segmentation via adversarial pre-segmentation of anterior segment OCT images. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 5291–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, C.L.; Mercado, C.; Venkateswaran, N.; Ruggeri, M.; Galor, A.; Garcia, A.; Sivaraman, K.R.; Fernandez, M.P.; Bermudez, A.; Dubovy, S.R. Use of High-Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography in the Surgical Management of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 206, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiri Joutei Hassani, R.; Liang, H.; El Sanharawi, M.; Brasnu, E.; Kallel, S.; Labbe, A.; Baudouin, C. En-face optical coherence tomography as a novel tool for exploring the ocular surface: A pilot comparative study to conventional B-scans and in vivo confocal microscopy. Ocul. Surf. 2014, 12, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunod, R.; Tahiri Joutei Hassani, R.; Robin, M.; Liang, H.; Rabut, G.; Baudouin, C.; Labbe, A. Evaluation of pterygium severity with en face anterior segment optical coherence tomography and correlations with in vivo confocal microscopy. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2021, 44, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Su, Y.; Cai, H.; Lin, L.; et al. Mooren’s ulcer: A multifactorial autoimmune peripheral ulcerative keratitis and current treatment protocols. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1630585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, M.; Tan, A.C.S.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Keane, P.A.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Sng, C.C.A.; Schmetterer, L. Optical coherence tomography angiography: A review of current and future clinical applications. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, A.H.; Chen, C.L.; Gahm, J.K.; Zheng, F.; Richter, G.M.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, R.K. Optical coherence tomography angiography: A comprehensive review of current methods and clinical applications. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 60, 66–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Zhao, F.; Du, C. Repeatability of ocular surface vessel density measurements with optical coherence tomography angiography. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, M.; Sim, D.A.; Keane, P.A.; Sng, C.C.; Egan, C.A.; Tufail, A.; Wilkins, M.R. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography for Anterior Segment Vasculature Imaging. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Jiang, D.; Tang, K.; Chen, W. Current clinical applications of anterior segment optical coherence tomography angiography: A review. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 261, 2729–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Cai, S.; Huang, Z.; Ding, P.; Du, C. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Pinguecula and Pterygium. Cornea 2020, 39, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Devarajan, K.; Tan, T.E.; Ang, M.; Mehta, J.S. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography for Evaluation of Reperfusion After Pterygium Surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 207, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, A.; Esfandiari, A.; Khalili, A.; Latifi, G.; Ghanbari, H.; Jafari, B.; Montazeriani, Z.; Rahimi, M.; Ghafarian, S. Assessment of conjunctival autograft reperfusion after pterygium surgery by optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A). Microvasc. Res. 2025, 157, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, N.J.; Marinkovic, M.; Bleeker, J.C.; Luyten, G.P.M.; Jager, M.J. Anterior Segment OCTA of Melanocytic Lesions of the Conjunctiva and Iris. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 222, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, A.; Araki-Sasaki, K.; Obata, H.; Ideta, S.; Kuroda, M.; Fujita, K.; Osakabe, Y.; Takahashi, K. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of inflamed juvenile conjunctival nevus and its treatment with immunosuppressant eye drops. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 69, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Karp, C.L.; Galor, A.; Al Bayyat, G.J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, J. Role of optical coherence tomography angiography in the characterization of vascular network patterns of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul. Surf. 2020, 18, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, H.; Masoumi, A.; Samadi, M.; Naghshtabrizi, N.; Aminizade, M.; Montazeriani, Z.; Khodaparast, M.; Montazeri, F.; Ghassemi, H. Optical coherence tomography angiography in evaluating the response of ocular surface squamous neoplasia to topical immunotherapy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theotoka, D.; Liu, Z.; Wall, S.; Galor, A.; Al Bayyat, G.J.; Feuer, W.; Jianhua, W.; Karp, C.L. Optical coherence tomography angiography in the evaluation of vascular patterns of ocular surface squamous neoplasia during topical medical treatment. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 25, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nampei, K.; Oie, Y.; Kiritoshi, S.; Morota, M.; Satoh, S.; Kawasaki, S.; Nishida, K. Comparison of ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygium using anterior segment optical coherence tomography angiography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2020, 20, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiseleva, T.N.; Saakyan, S.V.; Makukhina, V.V.; Lugovkina, K.V.; Milash, S.V.; Musova, N.F.; Zharov, A.A. The use of optical coherence tomography angiography in differential diagnosis of conjunctival melanocytic tumors. OV 2023, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binotti, W.W.; Mills, H.; Nose, R.M.; Wu, H.K.; Duker, J.S.; Hamrah, P. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography angiography in the assessment of ocular surface lesions. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 22, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederleithner, M.; de Sisternes, L.; Stino, H.; Sedova, A.; Schlegl, T.; Bagherinia, H.; Britten, A.; Matten, P.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Pollreisz, A.; et al. Ultra-Widefield OCT Angiography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottaridou, E.; Hatoum, A. Imaging of Anterior Segment Tumours: A Comparison of Ultrasound Biomicroscopy Versus Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography. Cureus 2024, 16, e52578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlin, C.J.; Sherar, M.D.; Foster, F.S. Subsurface ultrasound microscopic imaging of the intact eye. Ophthalmology 1990, 97, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, A.; Zhang, J.; Yao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Heiferman, M.J. Ultrasound in ocular oncology: Technical advances, clinical applications, and limitations. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.S.; Vora, G.K.; Gupta, P.K. Anterior Segment Imaging in Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016, 5435092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlin, C.J.; Foster, F.S. Conjunctival and Adnexal Disease. In Ultrasound Biomicroscopy of the Eye; Pavlin, C.J., Foster, F.S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 196–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.C.; Shen, S.C.; Huang, S.F.; Tsai, R.J. Ultrasound biomicroscopy in pigmented conjunctival cystic nevi. Cornea 2004, 23, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, T.; Soong, V.; Salvi, S.M.; Raynor, M.; Mudhar, H.; Goel, S.; Edwards, M. Primary corneal myxoma. Cornea 2008, 27, 1186–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.; Finger, P.T.; Iacob, C.E. Conjunctival myxoma: A case report with unique high frequency ultrasound (UBM) findings. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 66, 1629–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, H.; Shields, C.L.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Shields, J.A. Epibulbar schwannoma in a 17-year-old boy and review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 26, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.S.; Elner, V.M.; Demirci, H. Solitary epibulbar neurofibroma in older adult patients. Cornea 2015, 34, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, E.A.; Shields, C.L.; Bianciotto, C.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Shields, J.A. Oncocytic lesions (oncocytoma) of the ocular adnexa: Report of 15 cases and review of literature. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 28, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surakiatchanukul, T.; Sioufi, K.; Pointdujour-Lim, R.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Shields, J.A.; Shields, C.L. Caruncular Oncocytoma Mimicking Malignant Melanoma. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2017, 3, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, P.T.; Tran, H.V.; Turbin, R.E.; Perry, H.D.; Abramson, D.H.; Chin, K.; Della Rocca, R.; Ritch, R. High-frequency ultrasonographic evaluation of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meel, R.; Dhiman, R.; Sen, S.; Kashyap, S.; Tandon, R.; Vanathi, M. Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia with Intraocular Extension: Clinical and Ultrasound Biomicroscopic Findings. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2019, 5, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliki, S.; Jajapuram, S.D.; Maniar, A.; Taneja, S.; Mishra, D.K. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia with intraocular tumour extension: A study of 23 patients. Eye 2020, 34, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Rath, S.; Das, S.; Vemuganti, G.K.; Parulkar, G. Penetrating sclerokeratoplasty in massive recurrent invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 27, e39–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, A.A.; Farid, S.F. Management of intraepithelial and invasive neoplasia of the cornea and conjunctiva: A long-term follow up. Cornea 2009, 28, 986–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, C.L.; Yaghy, A.; Dalvin, L.A.; Vaidya, S.; Pacheco, R.R.; Perez, A.L.; Lally, S.E.; Shields, J.A. Conjunctival Melanoma: Outcomes based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer Clinical Classification (8th Edition) of 425 Patients at a Single Ocular Oncology Center. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 10, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.L.; Markowitz, J.S.; Belinsky, I.; Schwartzstein, H.; George, N.S.; Lally, S.E.; Mashayekhi, A.; Shields, J.A. Conjunctival melanoma: Outcomes based on tumor origin in 382 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 389–395.E1-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.L.; Shields, J.A.; Gunduz, K.; Cater, J.; Mercado, G.V.; Gross, N.; Lally, B. Conjunctival melanoma: Risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.H.; Prager, T.C.; Diwan, H.; Prieto, V.; Esmaeli, B. Ultrasound biomicroscopy for estimation of tumor thickness for conjunctival melanoma. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2007, 35, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, G.K.; Demirci, H.; Marr, B.; Mruthyunjaya, P. Advances in the management of conjunctival melanoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2017, 62, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, S.M.; Hurwitz, J.J.; Pavlin, C.J.; Howarth, D.J.; Nianiaris, N. Scleral melt after cryotherapy for conjunctival melanoma. Ophthalmology 1993, 100, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, E.; Grieshaber, M.C.; Tzankov, A.; Meyer, P. Persisting lesion of the conjunctiva. A masquerade syndrome? Ophthalmologe 2016, 113, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Son, Y.; Hyon, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Jeon, H.S. Relapsed acute myeloid leukemia presenting as conjunctival myeloid sarcoma: A case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, R.W.; Minhaz, A.T.; Wilson, D.L.; Orge, F.H. Clinical 3D Imaging of the Anterior Segment With Ultrasound Biomicroscopy. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.; Krema, H.; Saeed Kamil, Z.; Akbar, B.A.; Laperriere, N. Primary conjunctival basal cell carcinoma treated with plaque brachytherapy: A rare case report. Orbit 2025, 44, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachs, O.; Guthoff, R.F.; Aumann, S. In Vivo Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy. In High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology: New Frontiers in Biomedical Optics; Bille, J.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, A.D. Confocal Microscopy: Principles and Modern Practices. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2020, 92, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnke, M.; Masters, B.R. Confocal microscopy of the cornea. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1999, 18, 553–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minsky, M. Memoir on Inventing the Confocal Scanning Microscope. Scanning 1988, 10, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Miranda, A.; Guerrero-Becerril, J.; Ramirez, M.; Vera-Duarte, G.R.; Mangwani-Mordani, S.; Ortiz-Morales, G.; Navas, A.; Graue-Hernandez, E.O.; Alio, J.L. In vivo Confocal Microscopy for Corneal and Ocular Surface Pathologies: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 1817–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, C.; Mehta, J.S.; Liu, Y.C. A review of the application of in-vivo confocal microscopy on conjunctival diseases. Eye Vis. 2024, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourlis, C.; Seitz, B.; Roth, M.; Hamon, L.; Daas, L. Outcomes of Severe Fungal Keratitis Using in vivo Confocal Microscopy and Early Therapeutic Penetrating Keratoplasty. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Bian, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Shi, W. Clinical features and serial changes of Acanthamoeba keratitis: An in vivo confocal microscopy study. Eye 2020, 34, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, R.; Mulholland, P.J.; Hau, S.C. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Morphologic Features and Cyst Density in Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 217, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, R.; Yong, K.; Liu, Y.C.; Tong, L. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy in Different Types of Dry Eye and Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, R.; Dua, H.S.; Tong, L.; Kundu, G.; Khamar, P.; Gorimanipalli, B.; D’Souza, S. Role of in vivo confocal microscopy in dry eye disease and eye pain. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, A.S.; Gurdal, C.; Kosker, M.; Kesimal, B.; Kocamis, S.I. In vivo confocal microscopy findings of cornea and tongue mucosa in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2024, 99, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaq, A.; Colon, C.; Cavalcanti, B.M.; Aggarwal, S.; Qazi, Y.; Cruzat, A.; Jersey, C.; Critser, D.B.; Watts, A.; Beyer, J.; et al. Density and distribution of dendritiform cells in the peripheral cornea of healthy subjects using in vivo confocal microscopy. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 26, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocchi, S.; Mazzotta, C.; Sgheri, A.; Di Maggio, A.; Bagaglia, S.A.; Posarelli, M.; Ciompi, L.; Meduri, A.; Tosi, G.M. In vivo confocal microscopy: Qualitative investigation of the conjunctival and corneal surface in open angle glaucomatous patients undergoing the XEN-Gel implant, trabeculectomy or medical therapy. Eye Vis. 2020, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, A.M.; Wylegala, A.; Gargiulo, L.; Inferrera, L.; Russo, M.; Mencucci, R.; Orzechowska-Wylegala, B.; Aragona, E.; Mancini, M.; Quartarone, A. Corneal Sub-Basal Nerve Plexus in Non-Diabetic Small Fiber Polyneuropathies and the Diagnostic Role of In Vivo Corneal Confocal Microscopy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.K.; Catanese, S.; Blasco, H.; Pisella, P.J.; Corcia, P. Corneal nerves and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: An in vivo corneal confocal imaging study. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 3370–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Peng, H.; Wang, Q. In vivo confocal microscopy of sub-basal corneal nerves and corneal densitometry after three kinds of refractive procedures for high myopia. Int. Ophthalmol. 2023, 43, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulkas, S.; Aydin, F.O.; Turhan, S.A.; Toker, A.E. In vivo corneal confocal microscopy as a non-invasive test to assess obesity induced small fibre nerve damage and inflammation. Eye 2023, 37, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinotti, E.; Singer, A.; Labeille, B.; Grivet, D.; Rubegni, P.; Douchet, C.; Cambazard, F.; Thuret, G.; Gain, P.; Perrot, J.L. Handheld In Vivo Reflectance Confocal Microscopy for the Diagnosis of Eyelid Margin and Conjunctival Tumors. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.Z.; Xu, M.; Sun, S. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Observation of Cell and Nerve Density in Different Corneal Regions with Monocular Pterygium. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 6506134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhu, W.; Xu, J.; Zheng, T.; Sun, X. In vivo confocal microscopic evaluation of morphologic changes and dendritic cell distribution in pterygium. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 150, 650–655.E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadia, M.; Barabino, S.; Valente, C.; Rolando, M. Anatomical and immunological changes of the cornea in patients with pterygium. Curr. Eye Res. 2008, 33, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocal, H.; Seven, E.; Tekin, S.; Batur, M. In vivo corneal confocal microscopy findings in cases with pterygium: A case-control study. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2024, 58, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolek, B.; Wylegala, A.; Teper, S.; Kokot, J.; Wylegala, E. Treatment of conjunctival papilloma with topical interferon alpha-2b-case report. Medicine 2020, 99, e19181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Kiratli, H.; Soylemezoglu, F.; Irkec, M. In vivo confocal microscopy in a patient with conjunctival amyloidosis. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 36, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.O.C.; Alzanki, S.; Al Enazi, M.; Cherifi, N.; Cayrol, R.; Rahal, A.; Hardy, I.; Brunette, I.; Mabon, M. Conjunctival Neuroma After Corneal Neurotization in a Patient With Neurotrophic Keratopathy. Cornea 2025, 44, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Tan, C.Y.; Sun, C.; Yao, Y. Prominent corneal nerves in pure mucosal neuroma syndrome, a clinical phenotype distinct from multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.; Villaret, J.; Nguyen Kim, P.; Gabison, E.; Cochereau, I.; Doan, S. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy of Prominent Conjunctival and Corneal Nerves in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2B. Cornea 2019, 38, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Xu, C.; Ng, T.K.; Li, Z. Morphological characterization of nevi on the caruncle conjunctiva under in vivo confocal microscopy. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1166985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmer, E.M.; Mackert, M.J.; Zapp, D.M.; Kampik, A. In vivo confocal microscopy of pigmented conjunctival tumors. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2006, 244, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei-Ghanavati, M.; Mousavi, E.; Nabavi, A.; Latifi, G.; Mehrjardi, H.Z.; Mohebbi, M.; Ghassemi, H.; Mirzaie, F.; Zare, M.A. Changes in in vivo confocal microscopic findings of ocular surface squamous neoplasia during treatment with topical interferon alfa-2b. Ocul. Surf. 2018, 16, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, F.; Qu, H.; Hong, J. The clinical value of in vivo confocal microscopy for diagnosis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Eye 2012, 26, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrazzi, A.; Martone, G.; Pichierri, P.; Tosi, G.M.; Caporossi, A. Corneal invasion of ocular surface squamous neoplasia after clear corneal phacoemulsification: In vivo confocal microscopy analysis. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2008, 34, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, C.M.; Burchakchi, A.I.; Oscar, C.J. In vivo confocal microscopy study of ocular surface neoplasia manifesting after radial keratotomy and laser in situ keratomileusis. Cornea 2009, 28, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrini, A.; Martone, G.; Traversi, C.; Caporossi, A. In vivo confocal microscopy in a patient with recurrent conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008, 86, 690–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrozzani, R.; Lazzarini, D.; Dario, A.; Midena, E. In vivo confocal microscopy of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Eye 2011, 25, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguena, M.B.; van den Tweel, J.G.; Makupa, W.; Hu, V.H.; Weiss, H.A.; Gichuhi, S.; Burton, M.J. Diagnosing ocular surface squamous neoplasia in East Africa: Case-control study of clinical and in vivo confocal microscopy assessment. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichierri, P.; Martone, G.; Loffredo, A.; Traversi, C.; Polito, E. In vivo confocal microscopy in a patient with conjunctival lymphoma. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 36, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, K.; Janki, Z.R.; Bilicki, V.; Csutak, A.; Szalai, E. Artificial intelligence to enhance the diagnosis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AS-OCT | OCTA | UBM | IVCM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Low-coherence interfero35. | Motion contrast detection of blood flow | Acoustic reflection of high-frequency ultrasound waves (35–100 MHz) | Diffraction limited point excitation and signal detection |

| Image resolution | HR: 5–7 μm UHR: 1–5 μm | 5 μm (axial) resolution of 3 × 3 mm2 area | At 50 MHz, ~25 μm (axial) by ~50 μm (lateral) to a depth of ~5 mm | 0.2–4.0 μm (lateral) by 0.6–4.0 μm (axial) to a depth of ~130 μm |

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Najdawi, W.O.; Herskowitz, W.R.; Alba, D.E.; Badla, O.; Muthu, P.J.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L. Enhanced Imaging of Ocular Surface Lesions. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010289

Najdawi WO, Herskowitz WR, Alba DE, Badla O, Muthu PJ, Galor A, Karp CL. Enhanced Imaging of Ocular Surface Lesions. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010289

Chicago/Turabian StyleNajdawi, Wisam O., William R. Herskowitz, Diego E. Alba, Omar Badla, Pragat J. Muthu, Anat Galor, and Carol L. Karp. 2026. "Enhanced Imaging of Ocular Surface Lesions" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010289

APA StyleNajdawi, W. O., Herskowitz, W. R., Alba, D. E., Badla, O., Muthu, P. J., Galor, A., & Karp, C. L. (2026). Enhanced Imaging of Ocular Surface Lesions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010289