SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP Assessment in the Predicting of Cardiovascular Diseases and AF Recurrence in Hypertensive AF Patients Who Underwent Catheter Ablation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Atrial Fibrillation Diagnosis and Follow-Up

2.3. Atrial Fibrillation Cryoballoon Ablation Protocol

2.4. Follow-Ups

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical, Demographic, Treatment and Follow-Up Findings of the Study Groups

3.2. Laboratory and Echocardiography Findings of the Patients Groups

3.3. Clinical, Demographic, Treatment, Laboratory and Echocardiography Findings Associated with AF Recurrence

3.4. Clinical, Demographic, Treatment, Laboratory, and Echocardiography Findings Associated with CVD

3.5. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis to Identify Patients with AF Recurrence and CVD

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 1300. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4349. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, C.; Courand, P.Y.; Berge, C.; Harbaoui, B.; Lantelme, P. Impact of cortisol on blood pressure and hypertension-mediated organ damage in hypertensive patients. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikhonoff, V.; Kuznetsova, T.; Thijs, L.; Cauwenberghs, N.; Stolarz-Skrzypek, K.; Seidlerová, J.; Malyutina, S.; Gilis-Malinowska, N.; Swierblewska, E.; Kawecka-Jaszcz, K.; et al. Ambulatory blood pressure and long-term risk for atrial fibrillation. Heart 2018, 104, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Coca, A.; Kahan, T.; Boriani, G.; Manolis, A.S.; Olsen, M.H.; Oto, A.; Potpara, T.S.; Steffel, J.; Marín, F.; et al. Hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias: A consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and ESC Council on Hypertension, endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE). Europace 2017, 19, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conen, D.; Tedrow, U.B.; Koplan, B.A.; Glynn, R.J.; Buring, J.E.; Albert, C.M. Influence of systolic and diastolic blood pressure on the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Circulation 2009, 119, 2146–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lunardi, M.; Muhammad, F.; Shahzad, A.; Nadeem, A.; Combe, L.; Simpkin, A.J.; Sharif, F.; Wijns, W.; McEvoy, J.W. Performance of wearable watch-type home blood pressure measurement devices in a real-world clinical sample. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCORE2-Diabetes Working Group and the ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2-Diabetes: 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation in type 2 diabetes in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2544–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- SCORE2 Working Group and ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: New models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2439–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Pharmacological blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure: An individual participant-level data meta-analysis. Lancet 2021, 397, 1625–1636, Erratum in Lancet 2021, 397, 1884. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01069-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sundström, J.; Arima, H.; Jackson, R.; Turnbull, F.; Rahimi, K.; Chalmers, J.; Woodward, M.; Neal, B. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects of blood pressure reduction in mild hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettehad, D.; Emdin, C.A.; Kiran, A.; Anderson, S.G.; Callender, T.; Emberson, J.; Chalmers, J.; Rodgers, A.; Rahimi, K. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 387, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCORE2-OP Working Group and ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2-OP risk prediction algorithms: Estimating incident cardiovascular event risk in older persons in four geographical risk regions. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2455–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeis, S.; Gerstenfeld, E.P.; Kalman, J.; Saad, E.B.; Shamloo, A.S.; Andrade, J.G.; Barbhaiya, C.R.; Baykaner, T.; Boveda, S.; Calkins, H.; et al. 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, e31–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoun, I.; Layton, G.R.; Nizam, A.; Barker, J.; Abdelrazik, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Koya, A.; Lau, E.Y.M.; Zakkar, M.; Somani, R.; et al. Hypertension and Atrial Fibrillation: Bridging the Gap Between Mechanisms, Risk, and Therapy. Medicina 2025, 61, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaypakli, O.; Koca, H.; Şahin, D.Y.; Okar, S.; Karataş, F.; Koç, M. Association of P wave duration index with atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoballoon catheter ablation. J. Electrocardiol. 2018, 51, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, J.; Ferreira, A.M.; Cavaco, D.; Moscoso Costa, F.; Carmo, P.; Marques, H.; Morgado, F.; Mendes, M.; Adragão, P. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting atrial fibrillation recurrence after a first catheter ablation procedure—ATLAS score. Europace 2018, 20, f428–f435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canpolat, U.; Aytemir, K.; Yorgun, H.; Şahiner, L.; Kaya, E.B.; Çay, S.; Topaloğlu, S.; Aras, D.; Oto, A. The role of preprocedural monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio in prediction of atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoballoon-based catheter ablation. Europace 2015, 17, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karayiannides, S.; Widén, N.; Tsatsaris, G.; Rajamand-Ekberg, N.; Catrina, S.B. SCORE2-Diabetes Predicts the Risk of Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation in Individuals with Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, e104–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asad, Z.U.A.; Yousif, A.; Khan, M.S.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Stavrakis, S. Catheter Ablation Versus Medical Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrouche, N.F.; Brachmann, J.; Andresen, D.; Siebels, J.; Boersma, L.; Jordaens, L.; Merkely, B.; Pokushalov, E.; Sanders, P.; Proff, J.; et al. Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation with Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Biase, L.; Mohanty, P.; Mohanty, S.; Santangeli, P.; Trivedi, C.; Lakkireddy, D.; Reddy, M.; Jais, P.; Themistoclakis, S.; Dello Russo, A.; et al. Ablation Versus Amiodarone for Treatment of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure and an Implanted Device: Results from the AATAC Multicenter Randomized Trial. Circulation 2016, 133, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A.M.; Elbenawi, H.; Khan, U.; Almaadawy, O.; Turkmani, M.; Abdelmottaleb, W.; Essa, M.; Abuelazm, M.; Abdelazeem, B.; Asad, Z.U.A.; et al. Impact of Diagnosis to Ablation Time on Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation and Clinical Outcomes After Catheter Ablation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Reconstructed Time-to-Event Data. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2025, 18, e013261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koca, H.; Demirtas, A.O.; Kaypaklı, O.; Icen, Y.K.; Sahin, D.Y.; Koca, F.; Koseoglu, Z.; Baykan, A.O.; Guler, E.C.; Demirtas, D.; et al. Decreased left atrial global longitudinal strain predicts the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2020, 58, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Group I n = 67 | Group II n = 106 | Group III n = 93 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 46.1 ± 7.4 α,β | 56.7 ± 8.1 ¥ | 67.2 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Gender (Male), n | 39 (58%) | 59 (56%) | 46 (50%) | 0.505 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 4 (6%) a | 16 (15%) a | 36 (39%) b | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 137 ± 16 α | 139 ± 15 | 143 ± 14 | 0.037 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81 ± 13 | 81 ± 11 | 81 ± 10 | 0.998 |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 83 ± 13 | 82 ± 14 | 82 ± 112 | 0.898 |

| CHA2DS2-VA score | 1.0 ± 0.0 α,β | 1.15 ± 0.36 ¥ | 1.74 ± 0.71 | <0.001 |

| Propafenone use, n (%) | 17 (25%) | 22 (21%) | 22 (24%) | 0.764 |

| Flecainide use, n (%) | 20 (30%) | 18 (17%) | 24 (26%) | 0.143 |

| Amiodarone use, n (%) | 15 (23%) | 38 (36%) | 28 (30%) | 0.380 |

| Beta blocker or CCB use, n (%) | 61 (91%) | 91 (87%) | 86 (93%) | 0.837 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB use, n (%) | 36 (54%) | 58 (55%) | 53 (57%) | 0.674 |

| Oral anti-coagulant use, n (%) | 23 (34%) a | 50 (47%) a | 52 (56%) b | 0.009 |

| Atrial fibrillation recurrence, n (%) | 9 (13%) a | 17 (16%) a | 23 (25%) b | 0.035 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 0 (0%) a | 8 (8%) b | 14 (15%) b | 0.001 |

| Non-fatal stroke, n (%) | 0 (0%) a | 6 (6%) a | 8 (9%) b | 0.011 |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 0.294 |

| Cardiovascular mortality, n (%) | 0 (0%) a | 0 (0%) a | 4 (4%) b | 0.014 |

| Variables | Group I n = 67 | Group II n = 106 | Group III n = 93 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell (103/µL) | 7.32 ± 2.4 | 7.51 ± 2.3 | 7.39 ± 1.9 | 0.848 |

| Platelet count (103/µL) | 266 ± 71 | 250 ± 75 | 251 ± 77 | 0.481 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.4 ± 1.5 | 13.6 ± 1.4 | 13.5 ± 1.5 | 0.703 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 102 ± 19 | 103 ± 17 | 105 ± 21 | 0.353 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.70 ± 0.16 | 0.78 ± 0.48 | 0.76 ± 0.32 | 0.368 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 24.8 ± 6.7 α | 28.4 ± 7.8 | 29.6 ± 11 | 0.004 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 103 ± 18 α | 98 ± 14 | 94 ± 16 | 0.003 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 4.57 ± 1.4 | 4.86 ± 1.3 | 5.13 ± 1.8 | 0.069 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140 ± 2.4 | 140 ± 2.4 | 139 ± 2.9 | 0.123 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.28 ± 0.46 | 4.22 ± 0.42 | 4.25 ± 0.37 | 0.644 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 185 ± 43 α | 197 ± 51 | 204 ± 49 | 0.042 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 51.3 ± 13 | 49.6 ± 14 | 47.2 ± 9.6 | 0.109 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 124 ± 32 | 133 ± 34 | 132 ± 34 | 0.161 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 166 ± 81 | 174 ± 121 | 191 ± 143 | 0.382 |

| LVEF (%) | 59.5 ± 3.1 | 59.3 ± 3.7 | 58.8 ± 4.2 | 0.399 |

| LA dimension (mm) | 37.8 ± 4.3 | 36.9 ± 4.6 | 37.9 ± 4.4 | 0.230 |

| Variables | AF Recurrence (+) n = 49 | AF Recurrence (−) n = 217 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 183 ± 87 | 153 ± 85 | 0.036 |

| SCORE2(OP) CVD risk, <5%-5 to <10%-≥10%, n | 9-17-23 | 58-89-70 | 0.035 |

| Left atrium dimension (mm) | 40.4 ± 5.6 | 36.8 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Variables | Adverse CVD (+) n = 22 | Adverse CVD (−) n = 244 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 63.2 ± 12 | 57.2 ± 11 | 0.018 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 140 ± 15 | 135 ± 15 | 0.048 |

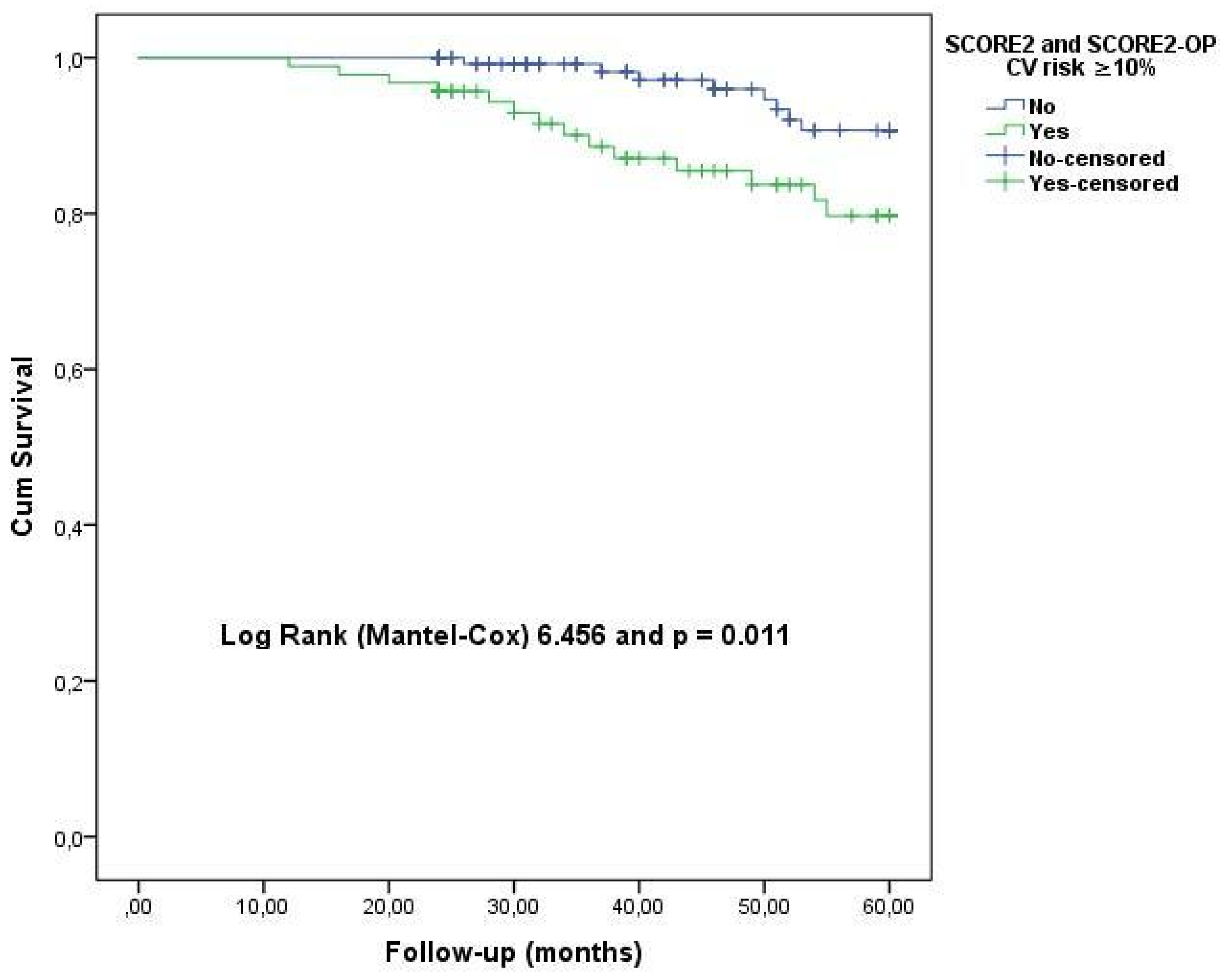

| SCORE2(OP) CVD risk, <5%-5 to <10%-≥10%, n | 0-8-14 | 67-98-79 | 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2-VA score | 1.77 ± 0.81 | 1.28 ± 0.53 | 0.010 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 31.4 ± 12 | 27.6 ± 11 | 0.028 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.33 ± 2.6 | 4.75 ± 1.3 | 0.009 |

| AF Recurrence | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

| SCORE2(OP) CVD risk (presence of ≥10%) | 2.448 | 1.324–4.126 | 0.005 |

| Left atrium dimension (each 1 mm) | 1.217 | 1.124–1.319 | <0.001 |

| CVD | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

| SCORE2(OP) (presence of CVD risk ≥ 10%) | 3.960 | 1.098–8.408 | <0.001 |

| CHA2DS2-VA score (each 1) | 3.257 | 1.067–7.318 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (each 1 mg/dL) | 1.976 | 1.359–2.873 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yüksel, G.; Ardıç, M.L.; Sumbul, H.E.; Koc, M. SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP Assessment in the Predicting of Cardiovascular Diseases and AF Recurrence in Hypertensive AF Patients Who Underwent Catheter Ablation. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010290

Yüksel G, Ardıç ML, Sumbul HE, Koc M. SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP Assessment in the Predicting of Cardiovascular Diseases and AF Recurrence in Hypertensive AF Patients Who Underwent Catheter Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010290

Chicago/Turabian StyleYüksel, Gülhan, Mustafa Lütfullah Ardıç, Hilmi Erdem Sumbul, and Mevlut Koc. 2026. "SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP Assessment in the Predicting of Cardiovascular Diseases and AF Recurrence in Hypertensive AF Patients Who Underwent Catheter Ablation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010290

APA StyleYüksel, G., Ardıç, M. L., Sumbul, H. E., & Koc, M. (2026). SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP Assessment in the Predicting of Cardiovascular Diseases and AF Recurrence in Hypertensive AF Patients Who Underwent Catheter Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010290