Establishing Diagnostic and Differential Diagnostic Criteria for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Clinical Spectrum of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

3.1. Progressive Muscular Atrophy (PMA)

3.2. Progressive Bulbar Atrophy (PBP)

3.3. Flail Arm Syndrome (FA, Flail Arm, Brachial Amyotrophic Diplegia, Vulpian–Bernhardt Syndrome)

3.4. Flail Leg Syndrome (FL)

3.5. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Hemiplegic Form (Mills Syndrome)

4. Diagnostic Criteria

- 1.

- Progressive motor impairment documented by history or repeated clinical assessment, preceded by normal motor function,

- AND

- 2.

- The presence of upper (A) and lower (B) motor neuron dysfunction in at least ONE body region (C) or lower motor neuron dysfunction in at least TWO body regions,

- 3.

- excluding other disease processes.

- (A) Upper motor neuron dysfunction implies at least one of the following:

- -

- increased tendon reflexes, including from the clinically involved muscle or adjacent muscle group.

- -

- presence of pathological reflexes, including Hoffmann’s sign, Babinski sign, crossed adductor reflex, or snout reflex

- -

- increased spastic muscle tone

- -

- weakness of voluntary movement that cannot be attributed to lower motor neuron damage or Parkinson’s disease

- (B) Lower motor neuron dysfunction in a given muscle requires either:

- Clinical examination evidence of muscle weakness and muscle atrophy

- or

- EMG abnormalities that must include both:

- -

- chronic neurogenic lesions, defined by motor unit potentials of prolonged duration and/or increased amplitude, with unit instability considered to confirm the diagnosis, but not necessary

- -

- and features of denervation, including fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves or fasciculations

- (C) Body regions are defined as bulbar, cervical, thoracic and lumbosacral. In order to speak of lower neural involvement, two limb muscles innervated by different roots and nerves must be involved, or it must be noted in one bulbar muscle, or in one thoracic muscle based on physical examination or changes in the EMG.

5. Electrophysiologic Criteria for Motor Neuron Disease Types

5.1. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

5.2. Progressive Muscular Atrophy

5.3. Progressive Bulbar Palsy

5.4. Flail Arm Syndrome

5.5. Flail Leg Syndrome

5.6. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Hemiplegic Form (Mills Syndrome)

5.7. Primary Lateral Sclerosis

6. Differential Diagnostics

6.1. Multifocal Motor Neuropathy

6.2. Monomelic Amyotrophy

6.3. O’Sullivan–McLeod Syndrome

6.4. Acute Motor Axonal Neuropathy

6.5. Motor Variant of Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy

6.6. Genetically Determined Motor Neuron Diseases

6.6.1. Spinal Muscular Atrophy

6.6.2. Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy

6.6.3. Distal Hereditary Motor Neuropathies

6.6.4. Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grad, L.I.; Rouleau, G.A.; Ravits, J.; Cashman, N.R. Clinical Spectrum of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a024117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenglet, T.; Camdessanché, J.P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or not: Keys for the diagnosis. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 173, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, L.A.; Salajegheh, M.K. Motor Neuron Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breza, M.; Koutsis, G. Kennedy’s disease (spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy): A clinically oriented review of a rare disease. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Chalabi, A.; Hardiman, O.; Kiernan, M.C.; Chiò, A.; Rix-Brooks, B.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Moving towards a new classification system. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, W.B.V.R.; Debona, R.; Nunes, P.P.; Assis, A.; Lopes, C.; Bortholin, T.; Dias, R.; Naylor, F.; Chieia, M.; Souza, P.; et al. Atypical Motor Neuron Disease variants: Still a diagnostic challenge in Neurology. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.L.; Goutman, S.A.; Petri, S.; Mazzini, L.; Savelieff, M.G.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2022, 400, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, H.; Vullaganti, M.; Kwan, J. Advances in molecular pathology, diagnosis, and treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMJ 2023, 27, e075037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

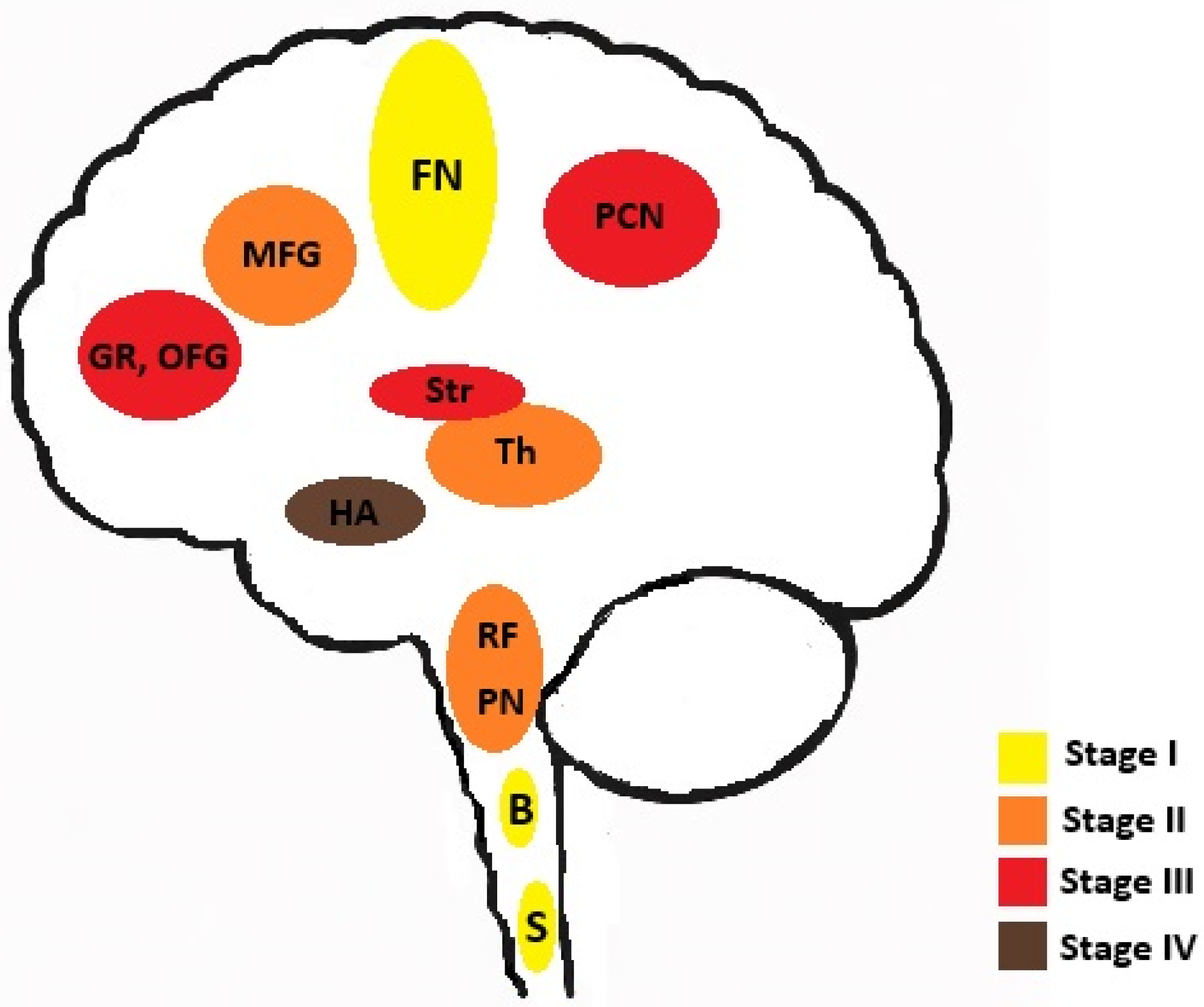

- Braak, H.; Brettschneider, J.; Ludolph, A.C.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Del Tredici, K. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis--a model of corticofugal axonal spread. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Liu, H.; Xiang, Z.; Qi, D.; Huang, J.H.; Wu, E.; Ding, X.; et al. Spreading of pathological TDP-43 along corticospinal tract axons induces ALS-like phenotypes in Atg5+/− mice. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štětkářová, I.; Ehler, E. Diagnostics of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Up to Date. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovic, M.; Müschen, L.H.; Brakemeier, S.; Machetanz, G.; Naumann, M.; Castro-Gomez, S. Current State and Future Directions in the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwathmey, K.G.; Corcia, P.; McDermott, C.J.; Genge, A.; Sennfält, S.; de Carvalho, M.; Ingre, C. Diagnostic delay in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 2595–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liewluck, T.; Saperstein, D.S. Progressive Muscular Atrophy. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg-Vos, R.M.; Visser, J.; Kalmijn, S.; Fischer, K.; de Visser, M.; de Jong, V.; de Haan, R.J.; Franssen, H.; Wokke, J.H.J.; Van den Berg, L.H. A long-term prospective study of the natural course of sporadic adult-onset lower motor neuron syndromes. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, H.P.; Gorges, M.; Del Tredici, K.; Ludolph, A.C.; Kassubek, J. The same cortico-efferent tract involvement in progressive bulbar palsy and in ‘classical’ ALS: A tract of interest-based MRI study. Neuroimage Clin. 2019, 24, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bublitz, S.K.; Weck, C.; Egger-Rainer, A.; Lex, K.; Paal, P.; Lorenzl, S. Palliative Care Challenges of Patients With Progressive Bulbar Palsy: A Retrospective Case Series of 14 Patients. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 700103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromicho, M.; Santos, M.O.; Pinto, S.; Swash, M.; De Carvalho, M. The flail-arm syndrome: The influence of phenotypic features. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2023, 24, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.N.; Choi, S.H.; Rha, J.H.; Kang, S.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Sung, J.J. Comparison between Flail Arm Syndrome and Upper Limb Onset Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Clinical Features and Electromyographic Findings. Exp. Neurobiol. 2014, 23, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacchiano, V.; Bonan, L.; Liguori, R.; Rizzo, G. Primary Lateral Sclerosis: An Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapalska, E.; Wrzesień, D.; Stępień, A. Case report: Flail leg syndrome in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with L144S SOD1 mutation. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1138668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornitzer, J.; Abdulrazeq, H.F.; Zaidi, M.; Bach, J.R.; Kazi, A.; Feinstein, E.; Sander, H.W.; Souayah, N. Differentiating Flail Limb Syndrome From Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, P.; Geevasinga, N.; Yiannikas, C.; Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S. Cortical contributions to the flail leg syndrome: Pathophysiological insights. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2016, 17, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiser, S.R.; Mitra, D.; Williams, T.L.; Baker, M.R. Mills’ syndrome revisited. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, H. A case of Mills’ syndrome: Initially characterized by one cerebral hemisphere atrophy and decreased brain metabolism then evolving into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 1311–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, B.R.; Miller, R.G.; Swash, M.; Munsat, T.L.; World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Mot. Neuron Disord. 2000, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, B.J.; Codd, M.B.; Corr, B.; Forde, C.; Frost, E.; Hardiman, O.M. Clinical features of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis according to the El Escorial and Airlie House diagnostic criteria: A population-based study. Arch. Neurol. 2000, 57, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.; Dengler, R.; Eisen, A.; England, J.D.; Kaji, R.; Kimura, J.; Mills, K.; Mitsumoto, H.; Nodera, H.; Shefner, J.; et al. Electrodiagnostic criteria for diagnosis of ALS. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, M.J.; Abrahams, S.; Goldstein, L.H.; Woolley, S.; Mclaughlin, P.; Snowden, J.; Mioshi, E.; Roberts-South, A.; Benatar, M.; Hortobágyi, T.; et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—Frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefner, J.M.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Baker, M.R.; Cui, L.-Y.; de Carvalho, M.; Eisen, A.; Grosskreutz, J.; Hardiman, O.; Henderson, R.; Matamala, J.M.; et al. A proposal for new diagnostic criteria for ALS. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 1975–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; UK MND Clinical Studies Group. Diagnosing ALS: The Gold Coast criteria and the role of EMG. Pract. Neurol. 2022, 22, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.; Gawel, M.J.; Cooper, P.W.; Farb, R.I.; Ang, L.C.; Gawal, M.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Correlation of clinical and MR imaging findings. Radiology 1995, 194, 263–270, Erratum in Radiology 1995, 196, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Gupta, A.; Nguyen, T.; Bourque, P. The “Motor Band Sign:“ Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 42, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.B.; Agarwal, A.; Mohamed, A.S.; Mohamed, K.H.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Bhatt, A.A.; Gupta, V.; Kumar, N.; Sechi, E.; Flanagan, E.P.; et al. Motor Neuron Diseases and Central Nervous System Tractopathies: Clinical-Radiologic Correlation and Diagnostic Approach. Radiographics 2025, 45, e240067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, E.; Jamroży, M.; Bielecki, M.; Bartoszek, M.; Gołębiowski, M.; Wojtaszek, M.; Kuźma-Kozakiewicz, M. Role of DTI-MRI parameters in diagnosis of ALS: Useful biomarkers for daily practice? Tertiary centre experience and literature review. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2022, 56, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbohm, A.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H.; Huppertz, H.-J.; Ludolph, A.C.; Müller, H.-P.; Kassubek, J. Involvement of cortico-efferent tracts in flail arm syndrome: A tract-of-interest-based DTI study. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pioro, E.P.; Turner, M.R.; Bede, P. Neuroimaging in primary lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2020, 21, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, J.; Dharmadasa, T.; Ma, Y.; Huynh, W.; Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M.C. Fasciculation intensity and disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2018, 129, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowser, R.; Turner, M.R.; Shefner, J. Biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Opportunities and limitations. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 7, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A clinical review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin Lari, A.; Ghavanini, A.A.; Bokaee, H.R. A review of electrophysiological studies of lower motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 1125–1136, Erratum in Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcia, P.; Bede, P.; Pradat, P.F.; Couratier, P.; Vucic, S.; de Carvalho, M. Split-hand and split-limb phenomena in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Pathophysiology, electrophysiology and clinical manifestations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, M. Split hand in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 90, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccolella, S.; Giugno, A.; Logroscino, G. Split phenomena in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Current evidences, pathogenetic hypotheses and diagnostic implications. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. The Neurophysiological Index in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Mot. Neuron Disord. 2004, 5, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekestein, W.A.; Schelhaas, H.J.; van Putten, M.J.; Stegeman, D.F.; Zwarts, M.J.; van Dijk, J.P. Motor unit number index (MUNIX) versus motor unit number estimation (MUNE): A direct comparison in a longitudinal study of ALS patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 1644–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwirth, C.; Barkhaus, P.E.; Burkhardt, C.; Castro, J.; Czell, D.; de Carvalho, M.; Nandedkar, S.; Stålberg, E.; Weber, M. Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX) detects motor neuron loss in pre-symptomatic muscles in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcio-Bezerra, M.L.; Abrahao, A.; Nunes, K.F.; Braga, N.I.D.O.; Oliveira, A.S.B.; Zinman, L.; Manzano, G.M. Motor unit number index and neurophysiological index as candidate biomarkers of presymptomatic motor neuron loss in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2018, 58, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wei, Q.; Ou, R.; Zhang, L.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shang, H. Neurophysiological index is associated with the survival of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 1730–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Thompson, J.M.; Mazurek, K.A.; Parra-Cantu, C.; Naddaf, E.; Gogineni, V.; Botha, H.; Jones, D.T.; Laughlin, R.S.; Barnard, L.; Staff, N.P. Artificial intelligence models using F-wave responses predict amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2025, 148, 2320–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, R.; Moaddel, R.; Kwan, J.Y.; Rasheed, M.; Ruffo, P.; Landeck, N.; Reho, P.; Vasta, R.; Calvo, A.; Moglia, C.; et al. A plasma proteomics-based candidate biomarker panel predictive of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3440–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umar, T.P.; Jain, N.; Papageorgakopoulou, M.; Shaheen, R.S.; Alsamhori, J.F.; Muzzamil, M.; Kostiks, A. Artificial intelligence for screening and diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2024, 25, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Quan, D. Electrodiagnostic Assessment of Motor Neuron Disease. Neurol. Clin. 2021, 39, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riku, Y.; Atsuta, N.; Yoshida, M.; Tatsumi, S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Mimuro, M.; Watanabe, H.; Ito, M.; Senda, J.; Nakamura, R.; et al. Differential motor neuron involvement in progressive muscular atrophy: A comparative study with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogucki, A.; Pigońska, J.; Szadkowska, I.; Gajos, A. Unilateral progressive muscular atrophy with fast symptoms progression. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2016, 50, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Tian, J.; Fan, D. Disease duration of progression is helpful in identifying isolated bulbar palsy of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.G.; Chen, L.; Tang, L.; Zhang, N.; Fan, D.S. Clinical Features of Isolated Bulbar Palsy of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Chinese Population. Chin. Med. J. 2017, 130, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, C.; Scelsa, S.N.; Macgowan, D.J. The clinical course of progressive bulbar palsy. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hübers, A.; Hildebrandt, V.; Petri, S.; Kollewe, K.; Hermann, A.; Storch, A.; Hanisch, F.; Zierz, S.; Rosenbohm, A.; Ludolph, A.C.; et al. Clinical features and differential diagnosis of flail arm syndrome. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Cui, B.; Fang, J.; Cui, L. Neurophysiological Differences between Flail Arm Syndrome and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Q.; Wang, S.; Shi, Y.; Chen, J. Flail arm syndrome patients exhibit profound abnormalities in nerve conduction: An electromyography study. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2019, 36, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Tian, J.; Fan, D. Differentiating Slowly Progressive Subtype of Lower Limb Onset ALS From Typical ALS Depends on the Time of Disease Progression and Phenotype. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 872500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellari, A.; Ciammola, A.; Silani, V. The pseudopolyneuritic form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Patrikios’ disease). Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 48, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Zhao, G.H.; Fang, J.J. Mills’ syndrome is a unique entity of upper motor neuron disease with N-shaped progression: Three case reports. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 6664–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; Talbot, K. Primary lateral sclerosis: Diagnosis and management. Pract. Neurol. 2020, 20, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; Barohn, R.J.; Corcia, P.; Fink, J.K.; Harms, M.B.; Kiernan, M.C.; Ravits, J.; Silani, V.; Simmons, Z.; Statland, J.; et al. Primary lateral sclerosis: Consensus diagnostic criteria. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, C.N.; Murphy, A.; Loci, L.; Mitsumoto, H.; Lomen-Hoerth, C.; Kisanuki, Y.; Simmons, Z.; Maragakis, N.J.; McVey, A.L.; Al-Lahham, T.; et al. Primary Lateral Sclerosis and Early Upper Motor Neuron Disease: Characteristics of a Cross-Sectional Population. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2016, 17, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.A.; Kojan, S.; Barohn, R.J.; Herbelin, L.; Nations, S.P.; Trivedi, J.R.; Jackson, C.E.; Burns, D.K.; Boyer, P.J.; Wolfe, G.I. Primary lateral sclerosis: Clinical and laboratory features in 25 patients. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2005, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.S.; Santos, M.O.; Gromicho, M.; Pinto, S.; Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. Electromyographic findings in primary lateral sclerosis during disease progression. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2996–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, S.; Micca, V.; Müller, H.P.; Huss, A.; Bachhuber, F.; Dorst, J.; Lulé, D.E.; Tumani, H.; Kassubek, J.; Ludolph, A.C. Primary lateral sclerosis: Application and validation of the 2020 consensus diagnostic criteria in an expert opinion-based PLS cohort. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Mittal, S.O.; Hu, W.T.; Josephs, K.A.; Sorenson, E.J.; Ahlskog, J.E. Does limited EMG denervation in early primary lateral sclerosis predict amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2022, 23, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile-Orazio, E. Multifocal motor neuropathy. J. Neuroimmunol. 2001, 115, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagale, S.V.; Bosch, E.P. Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block: Current issues in diagnosis and treatment. Semin. Neurol. 2003, 23, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwathmey, K.G.; Smith, A.G. Immune-Mediated Neuropathies. Neurol. Clin. 2020, 38, 711–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohnrade, C.; Seeliger, T.; Gingele, S.; Bjelica, B.; Skripuletz, T.; Petri, S. Diagnostic value of neurofilaments in differentiating motor neuron disease from multifocal motor neuropathy. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 4441–4452, Erratum in J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinveld, V.E.A.; Keritam, O.; Horlings, C.G.C.; Cetin, H.; Wanschitz, J.; Hotter, A.; Zirch, L.S.; Zimprich, F.; Topakian, R.; Müller, P.; et al. Multifocal motor neuropathy as a mimic of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Serum neurofilament light chain as a reliable diagnostic biomarker. Muscle Nerve 2024, 69, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.Z.; Dyck, P.J.; van den Berg, L.H.; Kiernan, M.C.; Taylor, B.V. Multifocal motor neuropathy: Controversies and priorities. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.A.; Clarke, A.E.; Harbo, T. A Practical Guide to Identify Patients With Multifocal Motor Neuropathy, a Treatable Immune-Mediated Neuropathy. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 8, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Niu, J.; Hu, N.; Ding, J.; Cui, L.; Liu, M. Neuromuscular ultrasound in combination with nerve conduction studies helps identify inflammatory motor neuropathies from lower motor neuron syndromes. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinka, M.; Chaudhry, V. Treatment of multifocal motor neuropathy. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2014, 16, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonioni, A.; Fonderico, M.; Granieri, E. Hirayama Disease: A Case of an Albanian Woman Clinically Stabilized Without Surgery. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, C.; Naqvi, W.M. Monomelic amyotrophy: A rare disease with unusual features (Hirayama disease). Pan. Afr. Med. J 2022, 42, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, M.; Mishra, M.; Mallick, A.K.; Swain, K.P.; Mishra, S. Monomelic amyotrophy with clinico-radiological and electrophysiological evaluation: A study from Eastern India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 1740–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, T.; Chang, Z.B.; Han, F.; Rui, Y. Benign monomelic amyotrophy with lower limb involvement in an adult: A case report. Medicine 2018, 97, e10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S.; Vats, A.; Gourie-Devi, M.; Sharma, A.; Verma, S.; Faruq, M.; Dhawan, U.; Taneja, V. Clinical and Genetic Analysis of A Father-Son Duo with Monomelic Amyotrophy: Case Report. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2023, 26, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourie-Devi, M.; Nalini, A. Long-term follow-up of 44 patients with brachial monomelic amyotrophy. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2003, 107, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschueren, A. Motor neuropathies and lower motor neuron syndromes. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 173, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamala, J.M.; Geevasinga, N.; Huynh, W.; Dharmadasa, T.; Howells, J.; Simon, N.G.; Menon, P.; Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M.C. Cortical function and corticomotoneuronal adaptation in monomelic amyotrophy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, D.K.; Prakash, A.; Gogoi, B.B.; Yadav, R.; Dhingani, D.; Sarma, B. The Importance of Flexion MRI in Hirayama Disease with Special Reference to Laminodural Space Measurements. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, W.B.V.R.; Nunes, P.P.; Lima E Teixeira, I.; Assis, A.; Naylor, F.; Chieia, M.; Souza, P.; Oliveira, A. O’Sullivan-McLeod syndrome: Unmasking a rare atypical motor neuron disease. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Shen, D.; Qian, M.; Cui, L.; Liu, M. Proposed criteria for the O’Sullivan McLeod syndrome: Case series and literature review. Neurol. Clinl. Neurosci. 2025, 13, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, A.; Al Aiyan, A.; Kishore, U.; Farrugia, M.E. Immune-Mediated Neuropathies: Pathophysiology and Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, P.A.; Van den Bergh, P.Y.K.; Hadden, R.D.M.; Avau, B.; Vankrunkelsven, P.; Attarian, S.; Blomkwist-Markens, P.H.; Cornblath, D.R.; Goedee, H.S.; Harbo, T.; et al. European Academy of Neurology/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on diagnosis and treatment of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2023, 28, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenthen, J.; Islam, B.; Islam, Z.; Mohammad, Q.D.; Maathuis, E.M.; Visser, G.H.; van Doorn, P.A.; Blok, J.H.; Endtz, H.P.; Jacobs, B.C. Changes in motor nerve excitability in acute phase Guillain-Barré syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2021, 63, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, S. Guillain-Barré syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Drugs 2004, 64, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, P.Y.K.; van Doorn, P.A.; Hadden, R.D.M.; Avau, B.; Vankrunkelsven, P.; Allen, J.A.; Attarian, S.; Blomkwist-Markens, P.H.; Cornblath, D.R.; Eftimov, F.; et al. European Academy of Neurology/Peripheral Nerve Society guideline on diagnosis and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: Report of a joint Task Force-Second revision. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 3556–3583, Erratum in Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegat, A.; Boisseau, W.; Maisonobe, T.; Debs, R.; Lenglet, T.; Psimaras, D.; Azoulay-Cayla, A.; Fournier, E.; Viala, K. Motor chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) in 17 patients: Clinical characteristics, electrophysiological study, and response to treatment. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2020, 25, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Sakurai, T.; Koumura, A.; Yamada, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Hozumi, I.; Yoshino, H.; Yuasa, T.; Inuzuka, T. Motor-dominant chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwabara, S.; Misawa, S. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1190, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menon, D.; Katzberg, H.D.; Bril, V. Treatment Approaches for Atypical CIDP. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 653734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentzos, M.; Anyfanti, C.; Kaponi, A.; Pandis, D.; Ioannou, M.; Vassilopoulos, D. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: A 6-year retrospective clinical study of a hospital-based population. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 14, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, H.; Niba, E.T.E.; Saito, T.; Okamoto, K.; Lee, T.; Takeshima, Y.; Awano, H.; Lai, P.-S. Clinical and Genetic Profiles of 5q- and Non-5q-Spinal Muscular Atrophy Diseases in Pediatric Patients. Genes 2024, 15, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Yokomura, M.; Osawa, Y.; Matsuo, K.; Kubo, Y.; Homma, T.; Saito, K. Genomic analysis of the SMN1 gene region in patients with clinically diagnosed spinal muscular atrophy: A retrospective observational study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhalchuk, K.; Zabnenkova, V.; Braslavskaya, S.; Chukhrova, A.; Ryadninskaya, N.; Dadaly, E.; Rudenskaya, G.; Sharkova, I.; Anisimova, I.; Bessonova, L.; et al. Rare Cause 5q SMA: Molecular Genetic and Clinical Analyses of Intragenic Subtle Variants in the SMN Locus. Clin. Genet. 2025, 108, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, H.; Niba, E.T.E.; Saito, T.; Okamoto, K.; Takeshima, Y.; Awano, H. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: The Past, Present, and Future of Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, E.; Sumner, C.J.; Muntoni, F.; Darras, B.T.; Finkel, R.S. Spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.M.; Mizell, J.; Bigdeli, L.; Paul, S.; Tellez, M.A.; Bartlett, A.; Heintzman, S.; Reynolds, J.E.; Sterling, G.B.; Rajneesh, K.F.; et al. Differential impact on motor unit characteristics across severities of adult spinal muscular atrophy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2023, 10, 2208–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.P.; Liu, G.C. MR imaging of primary skeletal muscle diseases in children. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002, 179, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.W.; Howell, K.; Place, A.; Long, K.; Rossello, J.; Kertesz, N.; Nomikos, G. Advances and limitations for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Eulate, G.; Theuriet, J.; Record, C.J.; Querin, G.; Masingue, M.; Leonard-Louis, S.; Behin, A.; Le Forestier, N.; Pegat, A.; Michaud, M.; et al. Phenotype Presentation and Molecular Diagnostic Yield in Non-5q Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Neurol. Genet. 2023, 9, e200087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioretti, C.; Andreotti, R.; Zuccaro, E.; Lieberman, A.P.; Basso, M.; Pennuto, M. Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: From molecular pathogenesis to pharmacological intervention targeting skeletal muscle. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2023, 71, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.H.; Lan, M.Y.; Liu, J.S.; Lai, S.L.; Chen, S.S.; Chang, Y.Y. Kennedy disease mimics amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A case report. Acta Neurol. Taiwan 2008, 17, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pedroso, J.L.; Vale, T.C.; Barsottini, O.G.; Oliveira, A.S.B.; Espay, A.J. Perioral and tongue fasciculations in Kennedy’s disease. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, R.; Sorarú, G.; Grunseich, C.; Fratta, P.; Zuccaro, E.; Pennuto, M.; Rinaldi, C. Beyond motor neurons: Expanding the clinical spectrum in Kennedy’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, A.; Katsuno, M.; Suzuki, K.; Banno, H.; Suga, N.; Hashizume, A.; Mano, T.; Hijikata, Y.; Nakatsuji, H.; Watanabe, H.; et al. Brugada syndrome in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Neurology 2014, 82, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korlipara, H.; Korlipara, G.; Pentyala, S. Brugada syndrome. Acta Cardiol. 2021, 76, 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battineni, A.; Gummi, R.; Mullaguri, N.; Govindarajan, R. Brugada syndrome in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, E.G.; Agosta, F.; Ferraro, P.M.; Querin, G.; Riva, N.; Bertolin, C.; Martinelli, I.; Lunetta, C.; Fontana, A.; Sorarù, G.; et al. Brain MRI shows white matter sparing in Kennedy’s disease and slow-progressing lower motor neuron disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 3102–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazir, M.; Nouioua, S. Distal hereditary motor neuropathies. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 180, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasquet, M.; Rojas-García, R.; Argente-Escrig, H.; Vázquez-Costa, J.F.; Muelas, N.; Vílchez, J.J.; Sivera, R.; Millet, E.; Barreiro, M.; Díaz-Manera, J.; et al. Distal hereditary motor neuropathies: Mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 1334–1343, Erratum in Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irobi, J.; De Jonghe, P.; Timmerman, V. Molecular genetics of distal hereditary motor neuropathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, R195–R202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murala, S.; Nagarajan, E.; Bollu, P.C. Hereditary spastic paraplegia. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyyazhagan, A.; Orlacchio, A. Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méreaux, J.L.; Banneau, G.; Papin, M.; Coarelli, G.; Valter, R.; Raymond, L.; Kol, B.; Ariste, O.; Parodi, L.; Tissier, L.; et al. Clinical and genetic spectra of 1550 index patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia. Brain 2022, 145, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, E.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Orlacchio, A. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: Genetic heterogeneity and common pathways. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 357, 114203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyyazhagan, A.; Kuchi Bhotla, H.; Pappuswamy, M.; Orlacchio, A. The Puzzle of Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia: From Epidemiology to Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.K. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: Clinico-pathologic features and emerging molecular mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| El Escorial Criteria (Revised) [26] | Awaji Criteria [28] | Gold Coast Criteria [30] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rationale for introducing criteria | Establishing classification for research and clinical purposes | Improving sensitivity and strengthening the role of electrophysiological findings | Improving sensitivity, simplifying the classification |

| Sensitivity | Lower | Higher | Highest |

| Specificity | Highest | High | Lower |

| Structure | Definite ALS: clinical presence of UMN and LMN signs in three regions Probable ALS: clinical UMN and LMN signs in at least two regions, some UMN signs above the LMN signs Probable ALS—Laboratory-supported: clinical UMN and LMN signs in one region or UMN signs alone in one region, and LMN signs defined by EMG criteria in at least two regions Possible ALS: clinical signs of UMN and LMN dysfunction in one region or UMN signs alone in two or more regions; or LMN signs rostral to UMN signs | Definite ALS: clinical or electrophysiological presence of UMN and LMN signs in three regions Probable ALS: clinical or electrophysiological UMN and LMN signs in at least two regions, some UMN signs above the LMN signs Possible ALS: clinical or electrophysiological signs of UMN and LMN dysfunction in one region or UMN signs alone in two or more regions; or LMN signs rostral to UMN signs | The presence of UMN and LMN dysfunction in at least one body region or LMN dysfunction in at least two body regions |

| Electrophysiological criteria | Signs of active denervation: 1. fibrillation potentials 2. positive sharp waves Signs of chronic denervation: 1. large motor unit potentials of increased duration with an increased proportion of polyphasic potentials, often of increased amplitude 2. reduced interference pattern with fringe rates higher than 10 Hz unless there is a significant UMN component 3. unstable motor unit potentials | Similar to El Escorial criteria + fasciculation potentials, preferably of complex morphology, equivalent to fibrillations and positive sharp waves | Similar to Awaji-shima criteria |

| Electrodiagnostic Criteria | Motor Nerve Conduction Criteria | Sensory Nerve Conduction Criteria | Needle Electromyography (EMG) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Activity | MUP | ||||

| SMA | SMA 1, 2 | Normal or slightly reduced amplitude of CMAP | Normal | Fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, fasciculation potentials | Large, rapidly firing with a late recruitment and reduced interference pattern Reinnervation more common in SMA 2 than SMA1 |

SMA 3, 4 | Reduced CMAP | Normal | Fasciculation potential occurs infrequently Complex repetitive discharges suggest a late stage | A late MUP recruitment reflects the loss of anterior horn cells High amplitude, long- duration MUP, reinnervation | |

SBMA | Reduced CMAP | Absent or low amplitude SNAP | Fibrillation potentials, CRD, reduced values of MUNE | Large MUP, long duration with reduced recruitment | |

dHMN | SIGMAR1-related dHMN with pyramidal signs | Significantly reduced CMAP | Normal | Denervated potentials localized symmetrically | Large MUP |

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 4 Autosomal Recessive | Mostly demyelinating NCV < 38 m/s | ||||

Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2, Autosomal Dominant | Reduction in amplitude mild slowing NCV > 38 m/s | Mild reduction in amplitude | Fasciculation potentials, fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves | Large long duration MUAPs with early recruitment | |

Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 1 Autosomal Dominant | Demyelination NCV < 38 m/s temporal dispersion is typically not seen | Fasciculation potentials, fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves A waves | Large, long duration MUAPs with early recruitment | ||

Charcot–Marie–Tooth X-linked | Demyelinative features but mostly distal motor nerve fibers with primary axonal degeneration mostly NCV >38 | Demyelinative features but mostly distal sensory nerve fibers/axonal degeneration | Fasciculation potentials, fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves | Large, long duration MUAPs with early recruitment | |

HSP—Hereditary spastic paraplegia | Mostly normal, depends on type HSP axonal/demyelinating | Mostly normal | Normal, fasciculation potentials might be seen | Large, long duration MUAPs with early recruitment | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dziadkowiak, E.; Marschollek, K.; Kwaśniak-Nowakowska, A.; Zimny, A.; Rałowska-Gmoch, W.; Boroń, M.; Koszewicz, M. Establishing Diagnostic and Differential Diagnostic Criteria for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010287

Dziadkowiak E, Marschollek K, Kwaśniak-Nowakowska A, Zimny A, Rałowska-Gmoch W, Boroń M, Koszewicz M. Establishing Diagnostic and Differential Diagnostic Criteria for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010287

Chicago/Turabian StyleDziadkowiak, Edyta, Karol Marschollek, Anna Kwaśniak-Nowakowska, Anna Zimny, Wiktoria Rałowska-Gmoch, Małgorzata Boroń, and Magdalena Koszewicz. 2026. "Establishing Diagnostic and Differential Diagnostic Criteria for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010287

APA StyleDziadkowiak, E., Marschollek, K., Kwaśniak-Nowakowska, A., Zimny, A., Rałowska-Gmoch, W., Boroń, M., & Koszewicz, M. (2026). Establishing Diagnostic and Differential Diagnostic Criteria for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010287