Effectiveness of Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transparency and Openness

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.3.1. Title and Abstract Screening

2.3.2. Full-Text Screening

- Records were included if they were available in English.

- Records were included if they were meta-analyses.

- Meta-analyses were included if at least five primary studies were included in the analysis.

- Meta-analyses were included if the majority (i.e., more than 50%) of their constituent samples comprised individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and/or its associated disorders, according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) [46]. These consist of:

- Schizophrenia

- Brief psychotic disorder

- Delusional disorder

- Schizoaffective disorder

- Schizophreniform disorder

- Schizotypal personality disorder

- Meta-analyses were included if they assessed the effectiveness of cognitive and behavioral interventions as a treatment. For the current umbrella review, we adopted a broad scope for selecting interventions to be included. We considered cognitive and behavioral interventions as “the informed and intentional application of clinical methods and interpersonal stances derived from established psychological principles for the purpose of assisting people to modify their behaviors, cognitions, emotions, and/or other personal characteristics in directions that the participants deem desirable” [46].

- We used the term “cognitive and behavioral interventions” as an overarching label for psychological treatments grounded in cognitive, behavioral, or cognitive–behavioral principles, consistent with the definition stated above. Accordingly, we included interventions classified as cognitive, behavioral, or cognitive–behavioral in nature, provided they involved structured therapeutic procedures intended to modify thoughts, behaviors, emotions, or functional engagement. These include but are not limited to CBT [31], music therapy [39], and group-based interventions [37]. As we wanted to examine the effectiveness of such interventions on the individual specifically, interventions that do not target the patient directly (e.g., family psychoeducation without the involvement of the individual) were excluded.

- For meta-analyses that contained a mix of both valid and invalid interventions, they were still included if information about the relevant cognitive and behavioral interventions were reported. In other words, a meta-analysis was included as long as it provided information about the efficacy of cognitive and behavioral interventions as a treatment; a meta-analysis was not included if they did not provide information about valid cognitive and behavioral interventions on its own.

- Meta-analyses were included if they reported the effect of cognitive and behavioral interventions on symptom-related outcomes, specifically total symptoms, positive symptoms, and/or negative symptoms.

- Meta-analyses were included if cognitive and behavioral interventions were compared to a control condition that was either a passive treatment control (e.g., wait-list control groups, treatment as usual, groups that did not receive any treatment) or active treatment control (e.g., medication, placebo). To increase the comparability of treatment effect sizes between the meta-analyses, control conditions where other forms of cognitive and behavioral interventions were used as a comparison group were not included.

2.3.3. Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Conversion of Effect Sizes

2.6. Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Search Outcome and Eligibility

3.2. Review Characteristics and Outcomes

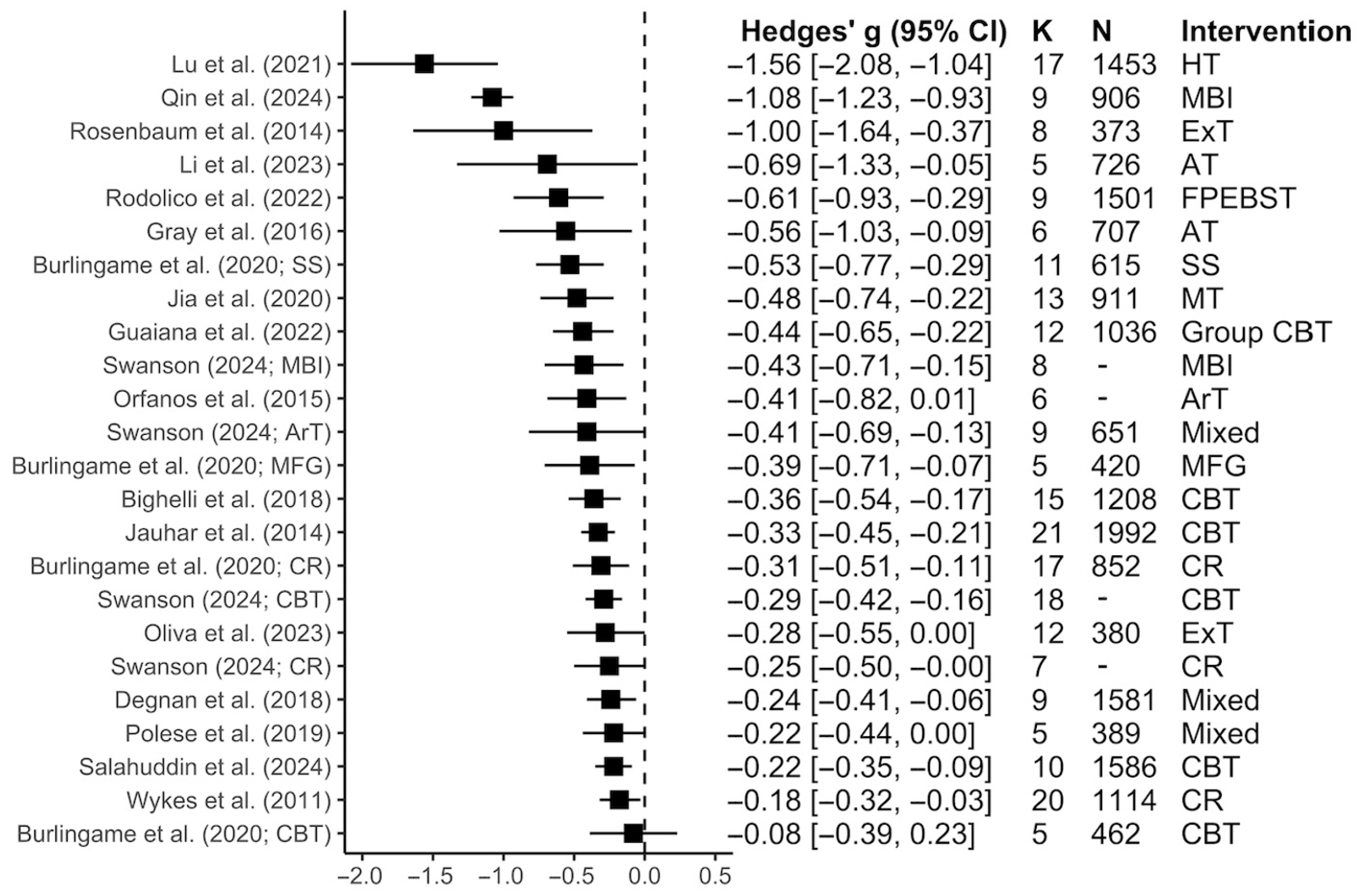

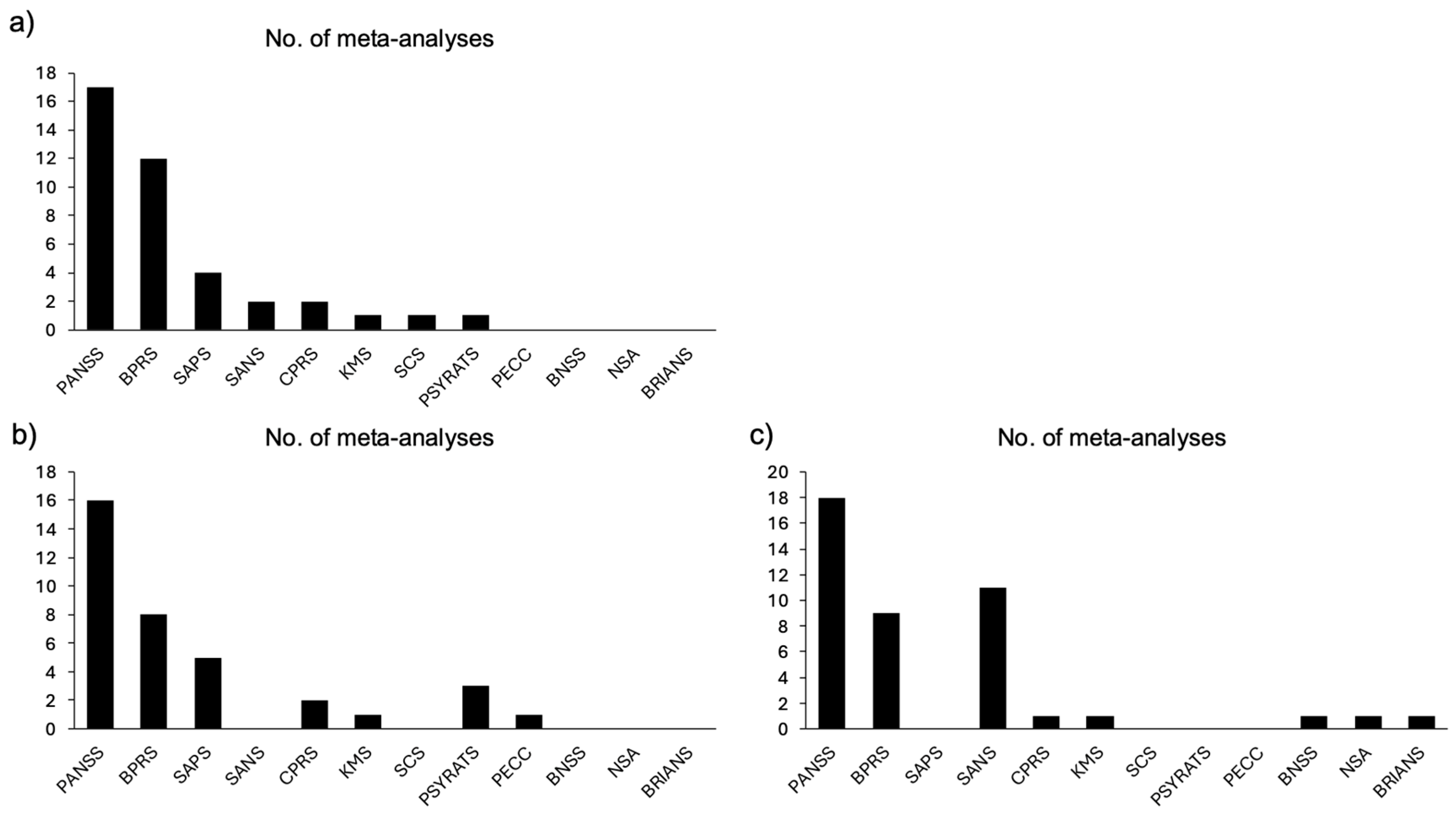

3.2.1. Total Symptoms

3.2.2. Positive Symptoms

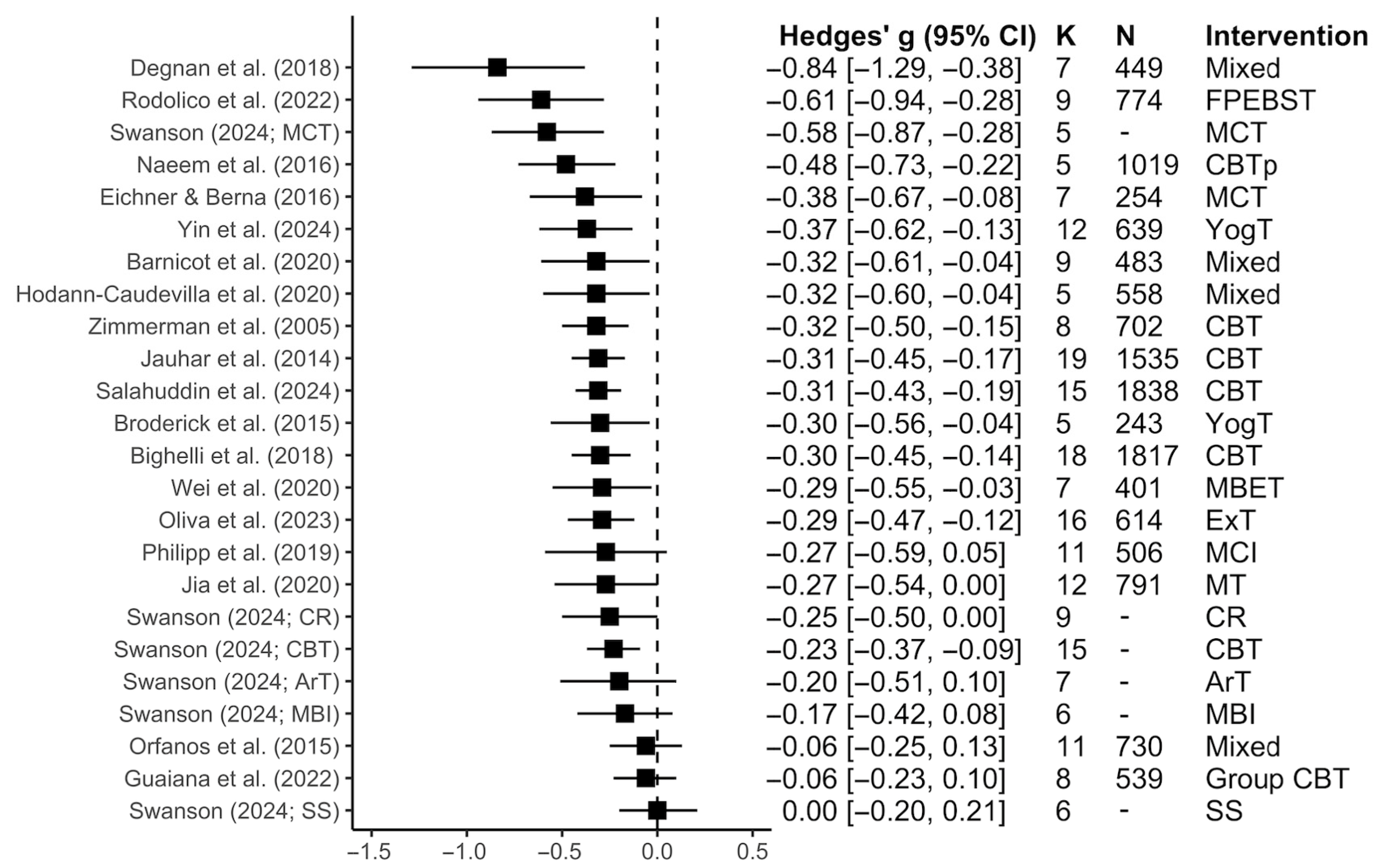

3.2.3. Negative Symptoms

3.2.4. Subgroup Analyses Within Each Symptom Dimension

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychological Association Schizophrenia. APA Dictionary of Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Insel, T.R. Rethinking Schizophrenia. Nature 2010, 468, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Chant, D.; Welham, J.; McGrath, J. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Schizophrenia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Thornicroft, G.; Tansella, M.; Becker, T.; Knapp, M.; Leese, M.; Schene, A.; Vazquez-Barquero, J.L. The Personal Impact of Schizophrenia in Europe. Schizophr. Res. 2004, 69, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, R.K.; Singh, P.; Midha, A.; Chugh, K. Schizophrenia: Impact on Quality of Life. Indian J. Psychiatry 2008, 50, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, N.; Reilly, J. Positive and Negative Impacts of Schizophrenia on Family Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Summary. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, M.; Mangalore, R.; Simon, J. The Global Costs of Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 30, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, D.P. The Economic Impact of Schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 4–6, discussion 28–30. Available online: https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/economic-impact-schizophrenia/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Davis, J.M.; Schaffer, C.B.; Killian, G.A.; Kinard, C.; Chan, C. Important Issues in the Drug Treatment of Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1980, 6, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, J.M. Treatment of Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987, 13, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, J.M.; Correll, C.U. Pharmacologic Treatment of Schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 12, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Reis Marques, T.; Howes, O.D. Schizophrenia—An Overview. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, P.C.; Frith, C.D. Perceiving Is Believing: A Bayesian Approach to Explaining the Positive Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correll, C.U.; Schooler, N.R. Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Review and Clinical Guide for Recognition, Assessment, and Treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.B.; Lehman, A.F.; Levine, J. Conventional Antipsychotic Medications for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1995, 21, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J.A.; Stroup, T.S.; McEvoy, J.P.; Swartz, M.S.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Perkins, D.O.; Keefe, R.S.E.; Davis, S.M.; Davis, C.E.; Lebowitz, B.D.; et al. Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, S.H.; North, S.W.; Shields, C.G. Schizophrenia: A Review. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 1821–1829. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0615/p1821.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Lally, J.; MacCabe, J.H. Antipsychotic Medication in Schizophrenia: A Review. Br. Med Bull. 2015, 114, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępnicki, P.; Kondej, M.; Kaczor, A.A. Current Concepts and Treatments of Schizophrenia. Molecules 2018, 23, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P.M.; Brain, C.; Scott, J. Nonadherence with Antipsychotic Medication in Schizophrenia: Challenges and Management Strategies. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2014, 5, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, S.V. Medication Adherence in Patients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2016, 51, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, K.A.; Smith, T.E.; Hull, J.W.; Piper, A.C.; Huppert, J.D. Predictors of Risk of Nonadherence in Outpatients With Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2002, 28, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, R.R.; Buchanan, R.W. Evaluation of Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1997, 23, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, O.D.; McCutcheon, R.; Agid, O.; de Bartolomeis, A.; van Beveren, N.J.M.; Birnbaum, M.L.; Bloomfield, M.A.P.; Bressan, R.A.; Buchanan, R.W.; Carpenter, W.T.; et al. Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group Consensus Guidelines on Diagnosis and Terminology. AJP 2017, 174, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.Y. Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia—The Role of Clozapine. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 1997, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucifora, F.C.; Woznica, E.; Lee, B.J.; Cascella, N.; Sawa, A. Treatment Resistant Schizophrenia: Clinical, Biological, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 131, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, D.; Fornaro, M.; Palermo, M.; De Luca, V.; de Bartolomeis, A. Treatment-Resistant to Antipsychotics: A Resistance to Everything? Psychotherapy in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia and Nonaffective Psychosis: A 25-Year Systematic Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Škodlar, B.; Henriksen, M.G. Toward a Phenomenological Psychotherapy for Schizophrenia. Psychopathology 2019, 52, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, S.; Laws, K.R.; McKenna, P.J. CBT for Schizophrenia: A Critical Viewpoint. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1233–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkington, D.; Dudley, R.; Warman, D.M.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Schizophrenia: A Review. FOC 2006, 4, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Li, W.; Li, C. Metacognitive Training for Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 149–157. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4526827/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Moritz, S.; Woodward, T.S. Metacognitive Training in Schizophrenia: From Basic Research to Knowledge Translation and Intervention. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkala, E.; Merinder, L. Psychoeducation for Schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, 2, CD002831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Merinder, L.B.; Belgamwar, M. Psychoeducation for Schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, CD002831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bighelli, I.; Salanti, G.; Huhn, M.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Krause, M.; Reitmeir, C.; Wallis, S.; Schwermann, F.; Pitschel-Walz, G.; Barbui, C.; et al. Psychological Interventions to Reduce Positive Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orfanos, S.; Banks, C.; Priebe, S. Are Group Psychotherapeutic Treatments Effective for Patients with Schizophrenia? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, Z. Effectiveness of Horticultural Therapy in People with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Liang, D.; Yu, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, C. The Effectiveness of Adjunct Music Therapy for Patients with Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporation for Digital Scholarship. Zotero; Version 6.0.26; Corporation for Digital Scholarship: Vienna, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.zotero.org (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Elsevier. Mendeley Reference Manager; Version 2.82.0; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.mendeley.com (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the Metafor Package. J. Stat. Soft. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- American Psychological Association. Recognition of Psychotherapy Effectiveness; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Koh, P.S.; Soh, X.C.; Hartanto, A.; Majeed, N.M. From Review to Synthesis: A Step-by-Step Methodological Guide to Systematic Reviews and Multilevel Meta-Analyses. PsyArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.; Shaheen, A.; Ramadan, A.; Hefnawy, M.T.; Ramadan, A.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Hassanein, M.E.; Ashour, M.E.; Flouty, O. Appraising Systematic Reviews: A Comprehensive Guide to Ensuring Validity and Reliability. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2023, 8, 1268045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon Martinez, E.; Ghattas Hasbun, P.E.; Salolin Vargas, V.P.; García-González, O.Y.; Fermin Madera, M.D.; Rueda Capistrán, D.E.; Campos Carmona, T.; Sanchez Cruz, C.; Teran Hooper, C. A Comprehensive Guide to Conduct a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. Medicine 2025, 104, e41868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WikiMedia List of Countries by Regional Classification. Available online: https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_regional_classification (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Aloe, A.M. Evaluation of Various Estimators for Standardized Mean Difference in Meta-Analysis. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, K.; Yu, Y.; Cai, H.; Li, J.; Zeng, J.; Liang, H. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Intervention in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 334, 115808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, S.; Tiedemann, A.; Sherrington, C.; Curtis, J.; Ward, P.B. Physical Activity Interventions for People with Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.H.; Hsieh, W.L.; Liu, W.I. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Adherence Therapy and Its Treatment Duration in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodolico, A.; Bighelli, I.; Avanzato, C.; Concerto, C.; Cutrufelli, P.; Mineo, L.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Siafis, S.; Signorelli, M.S.; Wu, H.; et al. Family Interventions for Relapse Prevention in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.; Bressington, D.; Ivanecka, A.; Hardy, S.; Jones, M.; Schulz, M.; von Bormann, S.; White, J.; Anderson, K.H.; Chien, W.-T. Is Adherence Therapy an Effective Adjunct Treatment for Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, G.M.; Svien, H.; Hoppe, L.; Hunt, I.; Rosendahl, J. Group Therapy for Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis. Psychotherapy 2020, 57, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaiana, G.; Abbatecola, M.; Aali, G.; Tarantino, F.; Ebuenyi, I.D.; Lucarini, V.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Pinto, A. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Group) for Schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD009608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, M. Various Psychological Treatments for Schizophrenia across Cognitive, Affective, Symptomatic, and Functional Domains: Results from Randomized Controlled Trials. Doctoral Dissertation, Alliant International University, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, Alhambra, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jauhar, S.; McKenna, P.J.; Radua, J.; Fung, E.; Salvador, R.; Laws, K.R. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for the Symptoms of Schizophrenia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Examination of Potential Bias. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, H.N.P.; Monteiro-Junior, R.S.; Oliva, I.O.; Powers, A.R. Effects of Exercise Intervention on Psychotic Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis and Hypothetical Model of Neurobiological Mechanisms. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 125, 110771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnan, A.; Baker, S.; Edge, D.; Nottidge, W.; Noke, M.; Press, C.J.; Husain, N.; Rathod, S.; Drake, R.J. The Nature and Efficacy of Culturally-Adapted Psychosocial Interventions for Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, N.H.; Schütz, A.; Pitschel-Walz, G.; Mayer, S.F.; Chaimani, A.; Siafis, S.; Priller, J.; Leucht, S.; Bighelli, I. Psychological and Psychosocial Interventions for Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wykes, T.; Huddy, V.; Cellard, C.; McGurk, S.R.; Czobor, P. A Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Remediation for Schizophrenia: Methodology and Effect Sizes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, F.; Khoury, B.; Munshi, T.; Ayub, M.; Lecomte, T.; Kingdon, D.; Farooq, S. Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp) for Schizophrenia: Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2016, 9, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner, C.; Berna, F. Acceptance and Efficacy of Metacognitive Training (Mct) on Positive Symptoms and Delusions in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis Taking into Account Important Moderators. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Alifujiang, H.; Wang, Y.; An, S.; Huang, H.; Fu, X.; Deng, H.; Chen, Y. Effects of Yoga on Clinical Symptoms, Quality of Life and Social Functioning in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2024, 93, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnicot, K.; Michael, C.; Trione, E.; Lang, S.; Saunders, T.; Sharp, M.; Crawford, M.J. Psychological Interventions for Acute Psychiatric Inpatients with Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 82, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodann-Caudevilla, R.M.; Díaz-Silveira, C.; Burgos-Julián, F.A.; Santed, M.A. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for People with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G.; Favrod, J.; Trieu, V.H.; Pomini, V. The Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Treatment on the Positive Symptoms of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 77, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, J.; Knowles, A.; Chadwick, J.; Vancampfort, D. Yoga versus Standard Care for Schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD010554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, R.; Kriston, L.; Lanio, J.; Kühne, F.; Härter, M.; Moritz, S.; Meister, R. Effectiveness of Metacognitive Interventions for Mental Disorders in Adults-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (METACOG). Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2019, 26, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.-X.; Yang, L.; Imm, K.; Loprinzi, P.D.; Smith, L.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Q. Effects of Mind-Body Exercises on Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, J.S.; van der Gaag, M.; Slofstra, C.; Knegtering, H.; Bruins, J.; Castelein, S. The Effect of Mind-Body and Aerobic Exercise on Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 279, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geretsegger, M.; Mössler, K.A.; Bieleninik, L.; Chen, X.-J.; Heldal, T.O.; Gold, C. Music Therapy for People with Schizophrenia and Schizophrenia-like Disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD004025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehle, M.; Böhl, M.C.; Pillny, M.; Lincoln, T.M. Efficacy of Psychological Treatments for Patients with Schizophre-nia and Relevant Negative Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2020, 2, e2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Papanastasiou, E.; Stahl, D.; Rocchetti, M.; Carpenter, W.; Shergill, S.; McGuire, P. Treatments of Neg-ative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis of 168 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, M.; Preti, A.; Edwards, C.; Dow, T.; Wykes, T. Cognitive Remediation for Negative Symptoms of Schizophre-nia: A Network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 52, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthorst, E.; Koeter, M.; van der Gaag, M.; Nieman, D.H.; Fett, A.-K.J.; Smit, F.; Staring, A.B.P.; Meijer, C.; de Haan, L. Adapted Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy Required for Targeting Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škodlar, B.; Henriksen, M.G.; Sass, L.A.; Nelson, B.; Parnas, J. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Schizophrenia: A Critical Evaluation of Its Theoretical Framework from a Clinical-Phenomenological Perspective. Psychopathology 2012, 46, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keepers, G.A.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Anzia, J.M.; Benjamin, S.; Lyness, J.M.; Mojtabai, R.; Servis, M.; Walaszek, A.; Buckley, P.; Lenzenweger, M.F.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. AJP 2020, 177, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liemburg, E.; Castelein, S.; Stewart, R.; van der Gaag, M.; Aleman, A.; Knegtering, H. Two Subdomains of Negative Symptoms in Psychotic Disorders: Established and Confirmed in Two Large Cohorts. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, D.E.; Kring, A.M.; Gard, M.G.; Horan, W.P.; Green, M.F. Anhedonia in Schizophrenia: Distinctions between Anticipatory and Consummatory Pleasure. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 93, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorschot, M.; Lataster, T.; Thewissen, V.; Lardinois, M.; Wichers, M.; van Os, J.; Delespaul, P.; Myin-Germeys, I. Emotional Experience in Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia—No Evidence for a Generalized Hedonic Deficit. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Horticultural Therapy Association Definitions and Positions. Available online: https://www.ahta.org/horticultural (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Oh, Y.-A.; Park, S.-A.; Ahn, B.-E. Assessment of the Psychopathological Effects of a Horticultural Therapy Program in Patients with Schizophrenia. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 36, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.-R.; Park, S.-A.; Ahn, B.-E. Reduced Stress and Improved Physical Functional Ability in Elderly with Mental Health Problems Following a Horticultural Therapy Program. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 38, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichrowski, M.; Whiteson, J.; Haas, F.; Mola, A.; Rey, M.J. Effects of Horticultural Therapy on Mood and Heart Rate in Patients Participating in an Inpatient Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation Program. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2005, 25, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, R.; Liu, W.; Wu, W. Effectiveness of Horticultural Therapy on Physical Functioning and Psychological Health Outcomes for Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2087–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, A.M.H.; Kam, M.; Mok, I. Horticultural Therapy Program for People with Mental Illness: A Mixed-Method Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrins-Margalis, N.M.; Rugletic, J.; Schepis, N.M.; Stepanski, H.R.; Walsh, M.A. The Immediate Effects of a Group-Based Horticulture Experience on the Quality of Life of Persons with Chronic Mental Illness. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2000, 16, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredin, S.S.D.; Kaufman, K.L.; Chow, M.I.; Lang, D.J.; Wu, N.; Kim, D.D.; Warburton, D.E.R. Effects of Aerobic, Resistance, and Combined Exercise Training on Psychiatric Symptom Severity and Related Health Measures in Adults Living With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 8, 753117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Woods-Giscombe, C. Influence of Dosage and Type of Music Therapy in Symptom Management and Rehabilitation for Individuals with Schizophrenia. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, G.; Houtmans, T.; Gold, C. The Additional Therapeutic Effect of Group Music Therapy for Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007, 116, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuml, J.; Froböse, T.; Kraemer, S.; Rentrop, M.; Pitschel-Walz, G. Psychoeducation: A Basic Psychotherapeutic Intervention for Patients with Schizophrenia and Their Families. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.; Adams, C.; Lucksted, A. Update on Family Psychoeducation for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2000, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C. Family Psychoeducation for People Living with Schizophrenia and Their Families. BJPsych Adv. 2018, 24, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinssen, R.K.; Liberman, R.P.; Kopelowicz, A. Psychosocial Skills Training for Schizophrenia: Lessons From the Laboratory. Schizophr. Bull. 2000, 26, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelowicz, A.; Liberman, R.P.; Zarate, R. Recent Advances in Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32, S12–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granholm, E.; Holden, J.; Link, P.C.; McQuaid, J.R. Randomized Clinical Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia: Improvement in Functioning and Experiential Negative Symptoms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, A.; Kurvey, A.; Sonavane, S. Family Psychoeducation for Schizophrenia: A Clinical Review. Malays. J. Psychiatry 2012, 21, 61–72. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/mjp/abstract/2012/21020/family_psychoeducation_for_schizophrenia__a.10.aspx (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Murray-Swank, A.B.; Dixon, L. Family Psychoeducation as an Evidence-Based Practice. CNS Spectr. 2004, 9, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, J.; Tng, G.Y.Q.; Hartanto, A. Potential and Pitfalls of Mobile Mental Health Apps in Traditional Treatment: An Umbrella Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020, 372.n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, | Type of Intervention * | Control Condition | Subgroup Type | Group | Number of Studies | Sample Size | Hedges’ g (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Year | |||||||

| Total symptoms | |||||||

| Jia et al. (2020) [39] | MT | TAU, WLC, Medication | Duration of MT | <3 months | 6 | - | −0.57 [−0.93, −0.20] |

| ≥3 months | 7 | - | −0.42 [−0.79, −0.05] | ||||

| Lu et al. (2021) [38] | HT | TAU | Type of environment | Hospital environment | 10 | 983 | −0.90 [−1.21, −0.59] |

| Non-hospital environment | 7 | 470 | −2.62 [−3.87, −1.38] | ||||

| Positive symptoms | |||||||

| Jia et al. (2020) [39] | MT | TAU, WLC, Medication | Duration of MT | <3 months | 4 | - | −0.53 [−0.96, −0.09] |

| ≥3 months | 8 | - | −0.15 [−0.46, 0.15] | ||||

| Zimmerman et al. (2005) [73] | CBT | TAU | Type of condition | Chronic | 6 | 569 | −0.30 [−0.53, −0.07] |

| Acute | 2 | 133 | −0.48 [−0.82, −0.13] | ||||

| Negative Symptoms | |||||||

| Jia et al. (2020) [39] | MT | TAU, WLC, Medication | Duration of MT | <3 months | 6 | - | −0.55 [−0.84, −0.26] |

| ≥3 months | 9 | - | −0.56 [−0.76, −0.36] | ||||

| Velthorst et al. (2015) [82] | Adapted CBT | TAU | Treatment setting | Group | 8 | 602 | 0.17 [−0.09, 0.44] |

| Individual | 20 | 1486 | −0.21 [−0.37, −0.05] | ||||

| Study population | Outpatient | 17 | 1227 | −0.12 [−0.31, 0.08] | |||

| In and outpatient | 7 | 585 | −0.05 [−0.36, 0.25] | ||||

| Inpatient | 4 | 276 | −0.20 [−0.57, 0.18] | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tan, G.X.D.; Hartanto, A.; Eun, Z.K.Y.; Hu, M.; Hsu, K.J.; Majeed, N.M. Effectiveness of Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010187

Tan GXD, Hartanto A, Eun ZKY, Hu M, Hsu KJ, Majeed NM. Effectiveness of Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Gabriel X. D., Andree Hartanto, Zoey K. Y. Eun, Meilan Hu, Kean J. Hsu, and Nadyanna M. Majeed. 2026. "Effectiveness of Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010187

APA StyleTan, G. X. D., Hartanto, A., Eun, Z. K. Y., Hu, M., Hsu, K. J., & Majeed, N. M. (2026). Effectiveness of Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010187