The Role of Interleukins in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

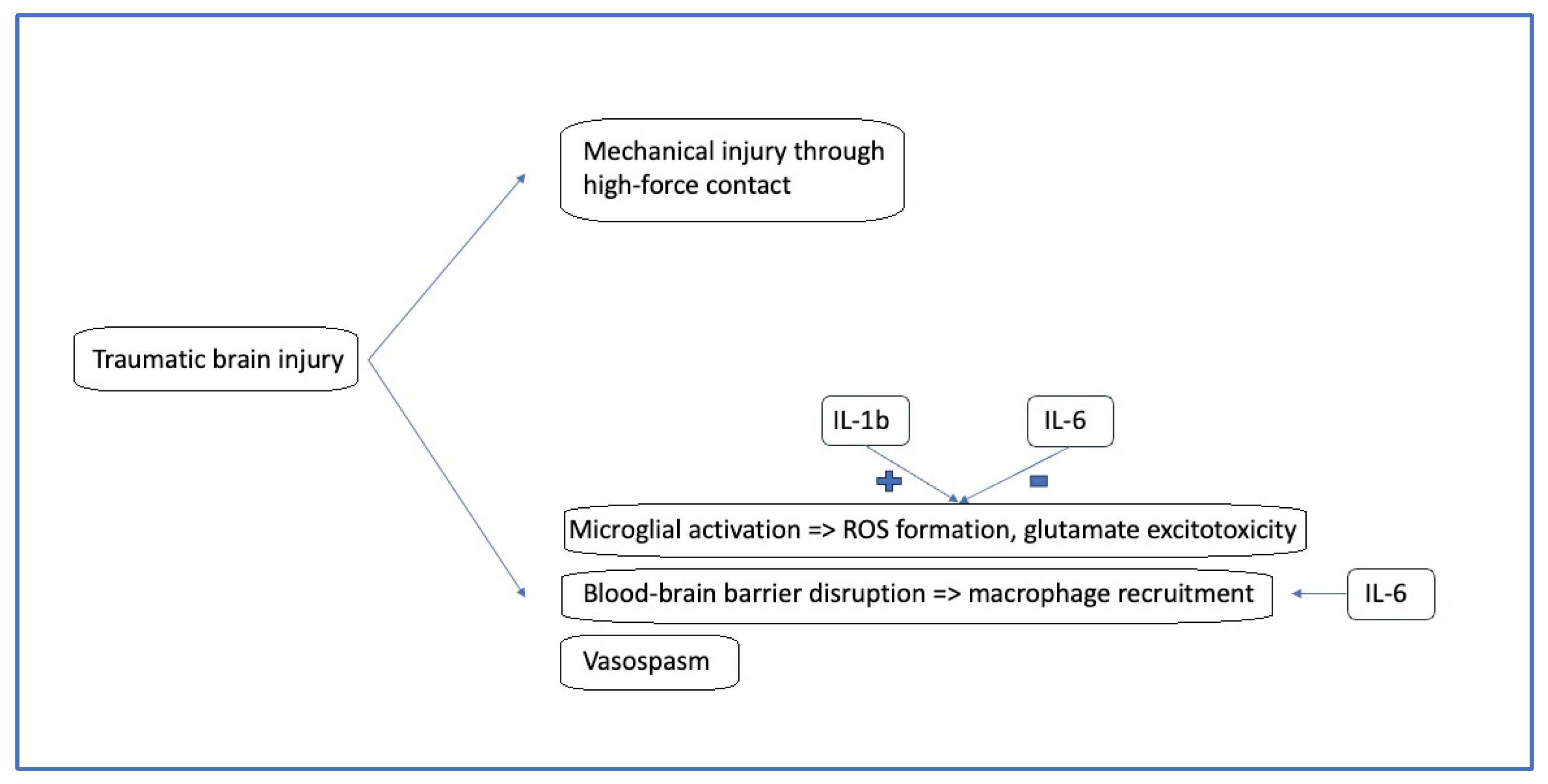

3. Pathophysiology of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury

4. ILs and Their Role in Pediatric TBI

4.1. Overview of ILs

4.2. Specific ILs and Their Roles in Pediatric TBI

4.2.1. IL-1β

4.2.2. IL-6

4.2.3. IL-8

4.2.4. IL-10

4.2.5. IL-17

5. Findings from Recent Clinical Studies

6. ILs in Specific TBI-Related Clinical Conditions

6.1. ILs and Concussion

6.2. ILs and Intracranial Hypertension

6.3. IL-1β and Post-Traumatic Epilepsy

7. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CBF | Cerebral blood flow |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT CXCL8 | Computed tomography C-X-C chemokine ligand family |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| INFγ | Interferon gamma |

| GCS | Glasgow coma scale |

| GDNF | Glial-derived neurotrophic factor |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acid protein |

| ICP | Intracranial pressure |

| IL | Interleukin |

| Jak1/Stat3 | Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MRI mTBI | Magnetic resonance imaging Mild traumatic brain injury |

| NFκB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NSE | Neuron specific enolase |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PTE | Post-traumatic epilepsy |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| S100B | S100 calcium binding protein B |

| sNCAM | Soluble neural cell adhesion molecule |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| SOCS | Suppressor of cytokine signaling |

| sTBI | Severe traumatic brain injury |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| UCH-L1 | Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 |

References

- de Souza, L.C.; Mazzu-Nascimento, T.; de Almeida Ballestero, J.G.; de Oliveira, R.S.; Ballestero, M. Epidemiological study of paediatric traumatic brain injury in Brazil. World Neurosurg. X 2023, 19, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; Adelson, P.D.; Andelic, N.; Bell, M.J.; Belli, A.; Bragge, P.; Brazinova, A.; Büki, A.; Chesnut, R.M.; et al. Traumatic brain injury: Integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 987–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, G.T.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Alosco, M.L.; Awwad, H.O.; Bazarian, J.J.; Bragge, P.; Corrigan, J.D.; Doperalski, A.; Ferguson, A.R.; Mac Donald, C.L.; et al. A new characterisation of acute traumatic brain injury: The NIH-NINDS TBI classification and nomenclature initiative. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 512–523, Erratum in Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(25)00393-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, K.; Khan, H.; Singh, T.G.; Kaur, A. Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanistic Insight on Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 1725–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttram, S.D.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Jackson, E.K.; Adelson, P.D.; Feldman, K.; Bayir, H.; Berger, R.P.; Clark, R.S.B.; Kochanek, P.M. Multiplex assessment of cytokine and chemokine levels in cerebrospinal fluid following severe pediatric traumatic brain injury: Effects of moderate hypothermia. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corps, K.N.; Roth, T.L.; McGavern, D.B. Inflammation and neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Malik, R.; Singh, G.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Mohan, S.; Albratty, M.; Albarrati, A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Pathogenesis and management of traumatic brain injury (TBI): Role of neuroinflammation and anti-inflammatory drugs. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, L.; Ramia, M.M.; Kelly, J.M.; Burks, S.S.; Pawlowicz, A.; Berger, R.P. Systematic review of clinical research on biomarkers for pediatric traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.C.; Mummareddy, N.; Wellons, J.C., 3rd; Bonfield, C.M. Epidemiology of global pediatric traumatic brain injury: Qualitative review. World Neurosurg. 2016, 91, 497–509.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hwang, S.K. Prognostic Value of Serum Levels of S100 Calcium-Binding Protein B, Neuron-Specific Enolase, and Interleukin-6 in Pediatric Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. World Neurosurg. 2018, 118, e534–e542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, R.J.; Murray, G.D.; Teasdale, G.M.; Stewart, J.; Day, I.; Lee, R.J.; Nicoll, J.A.R. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and outcome after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 1710–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.Y.; Jones, P.A.; Minns, R.A. Combining coma score and serum biomarker levels to predict unfavorable outcome following childhood brain trauma. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Engelhard, K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpa, R.O.; Ferguson, L.; Larson, C.; Bailard, J.; Cooke, S.; Greco, T.; Prins, M.L. Pathophysiology of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 696510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, M.; Patel, R.R.; Bajo, M. Ethanol and Cytokines in the Central Nervous System. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2018, 248, 397–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaretti, A.; Antonelli, A.; Riccardi, R.; Genovese, O.; Pezzotti, P.; Di Rocco, C.; Tortorolo, L.; Piedimonte, G. Nerve growth factor expression correlates with severity and outcome of traumatic brain injury in children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2008, 12, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, N.A.; Hewett, S.J.; Claycomb, R.J. Interleukin-1β in Central Nervous System Injury and Repair. Eur. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2012, 1, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Erta, M.; Quintana, A.; Hidalgo, J. Interleukin-6, a major cytokine in the central nervous system. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, H. Interleukin-2 and its receptors: Implications and therapeutic prospects in immune-mediated disorders of central nervous system. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 213, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giron, S.E.; Bjurstrom, M.F.; Griffis, C.A.; Ferrante, F.M.; Wu, I.I.; Nicol, A.L.; Grogan, T.R.; Burkard, J.F.; Irwin, M.R.; Breen, E.C. Increased Central Nervous System Interleukin-8 in a Majority Postlaminectomy Syndrome Chronic Pain Population. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozen, I.; Ruscher, K.; Nilsson, R.; Flygt, J.; Clausen, F.; Marklund, N. Interleukin-1 Beta Neutralization Attenuates Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Microglia Activation and Neuronal Changes in the Globus Pallidus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, J.L.; Giuliani, F.; Power, C.; Imai, Y.; Yong, V.W. Interleukin-1beta promotes oligodendrocyte death through glutamate excitotoxicity. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogal, B.; Hewett, S.J. Interleukin-1beta: A bridge between inflammation and excitotoxicity? J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaretti, A.; Genovese, O.; Aloe, L.; Antonelli, A.; Piastra, M.; Polidori, G.; Di Rocco, C. Interleukin 1beta and interleukin 6 relationship with paediatric head trauma severity and outcome. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2005, 21, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruol, D.L. IL-6 regulation of synaptic function in the CNS. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.J.; Kochanek, P.M.; Doughty, L.A.; Carcillo, J.A.; Adelson, P.D.; Clark, R.S.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Whalen, M.J.; DeKosky, S.T. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 in cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury in children. J. Neurotrauma 1997, 14, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaretti, A.; Antonelli, A.; Mastrangelo, A.; Pezzotti, P.; Tortorolo, L.; Tosi, F.; Genovese, O. Interleukin-6 and nerve growth factor upregulation correlates with improved outcome in children with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergenroeder, G.W.; Moore, A.N.; McCoy, J.P., Jr.; Samsel, L.; Ward, N.H., 3rd; Clifton, G.L.; Dash, P.K. Serum IL-6: A candidate biomarker for intracranial pressure elevation following isolated traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2010, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsipanis, C. Molecular Biomarkers in Traumatic Brain Injury. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Crete (School of Medicine), Heraklion, Greece, 2023. (In Greek). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushi, H.; Saito, T.; Makino, K.; Hayashi, N. IL-8 is a key mediator of neuroinflammation in severe traumatic brain injuries. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2003, 86, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossmann, T.; Stahel, P.F.; Lenzlinger, P.M.; Redl, H.; Dubs, R.W.; Trentz, O.; Schlag, G.; Morganti-Kossmann, M.C. Interleukin-8 released into the cerebrospinal fluid after brain injury is associated with blood-brain barrier dysfunction and nerve growth factor production. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1997, 17, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, M.J.; Carlos, T.M.; Kochanek, P.M.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Bell, M.J.; Clark, R.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Marion, D.W.; Adelson, P.D. Interleukin-8 is increased in cerebrospinal fluid of children with severe head injury. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 28, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strle, K.; Zhou, J.H.; Shen, W.H.; Broussard, S.R.; Johnson, R.W.; Freund, G.G.; Dantzer, R.; Kelley, K.W. Interleukin-10 in the brain. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 21, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, P.; Peruzzaro, S.; Kolli, N.; Andrews, M.; Al-Gharaibeh, A.; Rossignol, J.; Dunbar, G.L. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing interleukin-10 induces autophagy response and promotes neuroprotection in a rat model of TBI. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 5211–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waisman, A.; Hauptmann, J.; Regen, T. The role of IL-17 in CNS diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, M.; Zivkovic, N.; Cvetanovic, A.; Stojanovic, I.; Colic, M. IL-17 signalling in astrocytes promotes glutamate excitotoxicity: Indications for the link between inflammatory and neurodegenerative events in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2017, 11, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crichton, A.; Ignjatovic, V.; Babl, F.E.; Oakley, E.; Greenham, M.; Hearps, S.; Delzoppo, C.; Beauchamp, M.H.; Guerguerian, A.M.; Boutis, K.; et al. Interleukin-8 Predicts Fatigue at 12 Months Post-Injury in Children with Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.; Kelly, L.; Stacey, C.; Huggard, D.; Duff, E.; McCollum, D.; Leonard, A.; Boran, G.; Doherty, D.R.; Bolger, T.; et al. Mild-to-severe traumatic brain injury in children: Altered cytokines reflect severity. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Sheng, L.P.; Huang, Q.C.; Qian, T.; Qi, B.X. A pilot study on the effects of early use of valproate sodium on neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2023, 25, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, A.V.; Alunpipatthanachai, B.; Qiu, Q.; Clark-Bell, C.; Watanitanon, A.; Moore, A.; Chesnut, R.M.; Armstead, W.; Vavilala, M.S. Plasma Levels, Temporal Trends and Clinical Associations between Biomarkers of Inflammation and Vascular Homeostasis after Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. Dev. Neurosci. 2019, 41, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, P.; McCabe, S.E.; Eckner, J.T.; Schulenberg, J.E. Prevalence of concussion among US adolescents and correlated factors. JAMA 2017, 318, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.A.; Meehan, W.P.; Mannix, R. Duration and course of post- concussive symptoms. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, G.M.; Clarke, C.; Takagi, M.; Hearps, S.; Babl, F.E.; Davis, G.A.; Anderson, V.; Ignjatovic, V. Plasma Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Is a Predictor of Persisting Symptoms Post-Concussion in Children. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 1768–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakata, T.; Shiozaki, T.; Tasaki, O.; Ikegawa, H.; Inoue, Y.; Toshiyuki, F.; Hosotubo, H.; Kieko, F.; Yamashita, T.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Changes in CSF S100B and cytokine concentrations in early-phase severe traumatic brain injury. Shock 2004, 22, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.T.; DeLozier, S.J.; Chugani, H.T. Epilepsy Due to Mild TBI in Children: An Experience at a Tertiary Referral Center. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, M.L.; Ritter, A.C.; Failla, M.D.; Boles, J.A.; Conley, Y.P.; Kochanek, P.M.; Wagner, A.K. IL-1β associations with posttraumatic epilepsy development: A genetics and biomarker cohort study. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, P.M.; Thomas, N.J.; Clark, R.S.; Adelson, P.D.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Janesko, K.L.; Bayir, H.; Jackson, E.K.; Kochanek, P.M. Continuous versus intermittent cerebrospinal fluid drainage after severe traumatic brain injury in children: Effect on biochemical markers. J. Neurotrauma 2004, 21, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, B.D.; O’Brien, T.J.; Gimlin, K.; Wright, D.K.; Kim, S.E.; Casillas-Espinosa, P.M.; Webster, K.M.; Petrou, S.; Noble-Haeusslein, L.J. Interleukin-1 Receptor in Seizure Susceptibility after Traumatic Injury to the Pediatric Brain. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 7864–7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, L.; McKinley, W.I.; Valadka, A.B.; Newman, Z.C.; Nordgren, R.K.; Pramuka, P.E.; Barbosa, C.E.; Brito, A.M.P.; Loss, L.J.; Tinoco-Garcia, L.; et al. Diagnostic performance of GFAP, UCH-L1, and MAP-2 Within 30 and 60 Minutes of traumatic brain injury. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2431115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, P.E.; Jacobs, B.; Andriessen, T.M.; Lamers, K.J.; Borm, G.F.; Beems, T.; Edwards, M.; Rosmalen, C.F.; Vissers, J.L. GFAP and S100B are biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: An observational cohort study. Neurology 2010, 75, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posti, J.P.; Takala, R.S.; Runtti, H.; Newcombe, V.F.; Outtrim, J.; Katila, A.J.; Frantzén, J.; Ala-Seppälä, H.; Coles, J.P.; Hossain, M.I.; et al. The levels of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein and Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase-L1 during the first week after a traumatic brain injury: Correlations with clinical and imaging findings. Neurosurgery 2016, 79, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehouse, D.P.; Wilson, L.; Czeiter, E.; Buki, A.; Wang, K.K.W.; von Steinbüchel, N.; Zeldovich, M.; Steyerberg, E.; Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; et al. Association of blood-based biomarkers and 6-Month patient-reported outcomes in patients with mild TBI: A CENTER-TBI analysis. Neurology 2025, 104, e210040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeiro Coelho, L.M.; Teixeira, F.J.P.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Manolovitz, B.; Taylor, R.R.; Massad, N.; Kottapally, M.; Merenda, A.; Munoz Pareja, J.C.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; et al. Predictive value of nervous cell injury biomarkers in moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury: A network meta-analysis. Neurology 2025, 105, e213997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korley, F.K.; Jain, S.; Sun, X.; Puccio, A.M.; Yue, J.K.; Gardner, R.C.; Wang, K.K.W.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Yuh, E.L.; Mukherjee, P.; et al. Prognostic value of day-of-injury plasma GFAP and UCH-L1 concentrations for predicting functional recovery after traumatic brain injury in patients from the US TRACK-TBI cohort: An observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, F.; Luy, D.D.; Schaible, P.A.; Zywiciel, J.F.; Puccio, A.M.; Germanwala, A.V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of major blood protein biomarkers that predict unfavorable outcomes in severe traumatic brain injury. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2024, 242, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Marklund, N.; Czeiter, E.; Hutchinson, P.; Buki, A. Blood biomarkers for traumatic brain injury: A narrative review of current evidence. Brain Spine 2023, 4, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamian, A.; Farzaneh, H.; Khoshnoodi, M.; Maleki, N.; Rohatgi, S.; Ford, J.N.; Romero, J.M. Accuracy of GFAP and UCH-L1 in predicting brain abnormalities on CT scans after mild traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2025, 51, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoo, M.; Henry, J.; O’Halloran, P.J.; Brennan, P.; Husien, M.B.; Campbell, M.; Caird, J.; Javadpour, M.; Curley, G.F. S100B, GFAP, UCH-L1 and NSE as predictors of abnormalities on CT imaging following mild traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Neurosurg. Rev. 2022, 45, 1171–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagares, A.; de la Cruz, J.; Terrisse, H.; Mejan, O.; Pavlov, V.; Vermorel, C.; Payen, J.F.; BRAINI participants and investigators. An automated blood test for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) to predict the absence of intracranial lesions on head CT in adult patients with mild traumatic brain injury: BRAINI, a multicentre observational study in Europe. EBioMedicine 2024, 110, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, E.; Somera-Molina, K.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Watterson, D.M.; Wainwright, M.S. Suppression of acute proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine upregulation by post-injury administration of a novel small molecule improves long-term neurologic outcome in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2008, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachstetter, A.D.; Webster, S.J.; Goulding, D.S.; Morton, J.E.; Watterson, D.M.; Van Eldik, L.J. Attenuation of traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive impairment in mice by targeting increased cytokine levels with a small molecule experimental therapeutic. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachstetter, A.D.; Zhou, Z.; Rowe, R.K.; Xing, B.; Goulding, D.S.; Conley, A.N.; Sompol, P.; Meier, S.; Abisambra, J.F.; Lifshitz, J.; et al. MW151 inhibited IL-1β levels after traumatic brain injury with no effect on microglia physiological responses. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M.J.; Kochanek, P.M.; Doughty, L.A.; Carcillo, J.A.; Adelson, P.D.; Clark, R.S.B.; Whalen, M.J.; DeKosky, S.T. Comparison of the interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 response in children after severe traumatic brain injury or septic shock. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 1997, 70, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Interleukin | Onset of Action | Expressed by | Action | Association with TBI Severity | Clinical Outcome Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Moderate increase in the first two hours, remains high after 48 h [17] | Microglia, astrocytes, endothelial cells [11,22] | Pro-inflammatory [11,22,24] | Early rise was associated with severe head injury [11,22] | Poor [11,22] |

| IL-6 | Rapid increase followed by decline after 48 h [17] | Astrocytes, neurons [26] | Anti-inflammatory [26] | Mixed results [9,25,26,27] | Mixed results, mainly favorable outcomes [11,17,28] |

| IL-8 | Marked increase in the first 12 h [33] | Microglia, macrophages, endothelial cells [31] | Mixed (chemotactic, neutrophil-activating, neuroprotective) [32,33] | Associated with higher mortality [8,33] | Predicts post-injury fatigue [38] |

| Authors | Year | Study Design | Type of Specimen | No of Patients | ILs Analyzed | Primary Findings | Secondary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryan et al. [39] | 2022 | Prospective, controlled | Plasma | 208 | IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-17A | IL-6 was increased in every patient with TBI, and could distinguish mTBI from sTBI | IL-6/IL-8 ratio was the best marker regarding the differential diagnosis of sTBI from mTBI |

| Crichton et al. [38] | 2021 | Prospective, uncontrolled | Serum | 87 | IL-6 and IL-8 | IL-8 levels can predict post-injury fatigue | - |

| Liu et al. [40] | 2023 | Prospective, controlled | Serum | 45 | IL-1β | High IL-1β levels upon submission | Sodium valproate can reduce inflammation and improve prognosis |

| Lele et al. [41] | 2009 | Prospective, uncontrolled | Plasma | 28 | IL-6 | Patients with sTBI had higher IL-6 levels at day 10 compared to mTBI | Higher IL-6 levels tended to occur in patients with lower GCS |

| Chiaretti et al. [28] | 2008 | Prospective, controlled | CSF | 29 | IL-1β, IL-6 | IL-1β correlated with severity and poor outcome, no association for IL-6 | No association between IL-6 levels and GCS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Komiotis, C.; Mavridis, I.; Pyrgelis, E.-S.; Agapiou, E.; Meliou, M.; Birbilis, T. The Role of Interleukins in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Synthesis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010186

Komiotis C, Mavridis I, Pyrgelis E-S, Agapiou E, Meliou M, Birbilis T. The Role of Interleukins in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Synthesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010186

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomiotis, Christodoulos, Ioannis Mavridis, Efstratios-Stylianos Pyrgelis, Eleni Agapiou, Maria Meliou, and Theodossios Birbilis. 2026. "The Role of Interleukins in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Synthesis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010186

APA StyleKomiotis, C., Mavridis, I., Pyrgelis, E.-S., Agapiou, E., Meliou, M., & Birbilis, T. (2026). The Role of Interleukins in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Synthesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010186