Physical Therapist-Led Therapeutic Exercise and Mobility in Adult Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review of Operational Definitions, Dose Progression, Safety, and Documentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

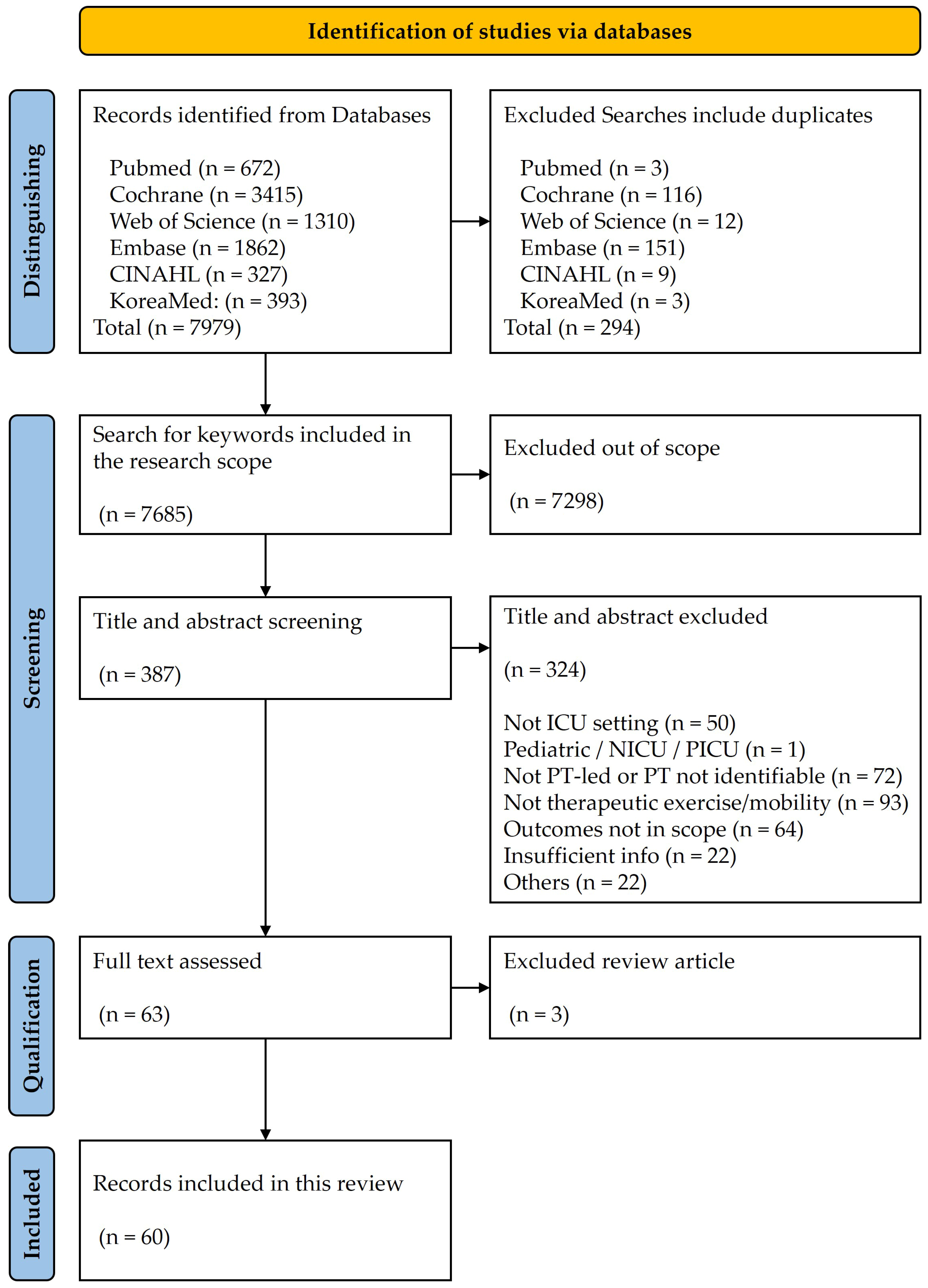

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Charting and Items

2.6. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

| Term & Operational Definition | Inclusion/Exclusion | Activity Level | PT-Led Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-bed therapeutic exercise (active/active-assisted): Goal-directed limb/trunk exercises (supine/semi-recumbent) with planned sets-reps to build activity tolerance and neuromuscular activation [31,32,33,34]. | Include: active/active-assisted exercises with dosing; Exclude: routine passive positioning or hygiene-only repositioning. | In-bed (level 1) | Assessment: ROM/MRC sum score; Prescription: sets-reps and rest; Progression: ↑ reps/resistance → sitting on EOB. |

| Sitting at EOB: Supported/unsupported sitting with postural control and orthostatic adaptation tasks [35,36,37,38,39]. | Include: ≥1–2 min EOB tasks; Exclude: brief roll without therapeutic intent. | Sitting on EOB (level 2) | Assessment: orthostatic response; Prescription: minutes/sessions; Progression: ↑ duration/complexity → sit-to-stand. |

| Sit-to-stand and static standing: Task-specific transitions from sitting to standing and stand-hold with assistance as required [33,37,39,40,41]. | Include: repetitions for endurance/strength; Exclude: passive hoist with no active effort. | OOB transition (level 3) | Assessment: hemodynamics/SpO2; Prescription: reps and rest; Progression: ↓ assist → marching/mini-squats. |

| Bed-to-chair transfer: Active transfer (pivot/slide/stand-step) with secure line/tube management [32,36,39,40,41,42]. | Include: PT-guided OOB transfer; Exclude: transport-only transfers without exercise intent. | OOB transfer (level 4) | Assessment: line security/RASS; Prescription: daily transfer goal; Progression: ↓ assist devices → independence. |

| Ambulation/gait (assisted to independent): Progressive walking focusing on distance, speed, and safety with aids as needed [32,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. | Include: goal-based ambulation; Exclude: standing pivot only. | Ambulation (level 5) | Assessment: IMS/FSS-ICU gait parameters; Prescription: distance/time targets; Progression: ↑ distance/speed, ↓ assist. |

| Task-specific functional training: Bed mobility, transfers, reaching/handling, dual-tasking aligned with discharge goals [36,37,46,47,48]. | Include: repeated practice of ADL-relevant tasks; Exclude: non-goal passive movements. | Across levels | Assessment: FSS-ICU/PFIT-s components; Prescription: task reps/sets; Progression: ↑ complexity/dual-task. |

| Therapeutic Devices | Inclusion/Exclusion | Activity Level | PT-Led Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper-limb ergometer exercise: Arm ergometry with set cadence/resistance for aerobic/strength goals [44,47,49]. | Include: cadence/RPE-dosed sessions; Exclude: unplanned ROM only. | In-bed/EOB/OOB | Assessment: RPE/HR; Prescription: RPM/Watt/min; Progression: ↑ cadence/resistance. |

| In-bed cycle ergometry (lower limbs): Bedside leg cycling (active/assisted) with graded cadence and duration [31,47,50]. | Include: protocolized cycling with safety screen; Exclude: CPM-type passive motion without rehab intent. | In-bed → OOB | Assessment: oxygenation/hemodynamics; Prescription: minutes and cadence; Progression: ↑ active time/gear. |

| Bedside treadmill/BWST: Harness-assisted treadmill stepping enabling early gait with unloading for safety [51,52]. | Include: BWST with harness and team support; Exclude: unstable patients without safeguards. | OOB high-level | Assessment: orthostatic/line security; Prescription: speed/min; Progression: ↑ speed, ↓ unloading. |

| Robotic-/suspension-assisted mobilization: Robotic or suspension systems to facilitate early standing/stepping with controlled assistance [53,54]. | Include: device use under PT control; Exclude: device-only passive movement without goals. | OOB assistive | Assessment: device fit/safety; Prescription: session min and task blocks; Progression: ↓ assistance, ↑ task demand. |

| NMES: Surface electrical stimulation adjunct to exercise to mitigate atrophy or prime muscles [55,56,57,58,59]. | Include: NMES with therapeutic goals; Exclude: NMES alone as sole intervention without rehab plan. | Co-interventions to various exercises | Assessment: target muscle/parameters; Prescription: pulse width/frequency/on–off; Progression: ↑ intensity/duration. |

| VR or combined cognitive-physical (adjunct): VR or cognitive modules integrated with exercise to enhance engagement/dual-task capacity [46,60,61]. | Include: interactive modules with goals; Exclude: passive viewing only. | Complementary modalities across levels | Assessment: cognitive tolerance; Prescription: minutes and difficulty; Progression: ↑ challenge/dual-task load. |

| Operational Statement | PT | OT | RN | MD | RT | Co-Management Notes | Documentation Phrase Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT explicitly stated as prescriber/leader of therapeutic exercise and mobility [36,38,62,63]. | ✓ | ✓ | Orders may be co-signed per policy. | Physical Therapist prescribed and progressed therapeutic exercise and mobility per protocol. | |||

| PT delivers intervention; leadership implied within interdisciplinary protocol [36,38,62,64]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Protocol defines roles; MD approves plan of care. | Mobility provided by PT within the interdisciplinary early rehabilitation protocol. | |

| Standing order set or automatic PT consult within 24–48 h of ICU admission [32,36,38]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | RN triggers consult via protocol; MD approves; PT initiates assessment within timeframe. | Automatic PT consult triggered within 48 h of admission per ICU order set. | ||

| Algorithmic screening (e.g., daily checklist) identifies candidates for PT-led mobility [44,65]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Checklist covers hemodynamics, oxygenation, sedation, and lines; team confirms eligibility on rounds. | Daily mobility screen completed; patient cleared for PT-led session. | |

| Target light sedation (e.g., RASS −1 to +1) to enable active participation [5,6,8,13,29]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MD and RN titrate sedation; PT aligns timing/intensity. | RASS −1 to 0 prior to sit-to-stand; session intensity adjusted accordingly. | ||

| Mobility may proceed on low-dose vasoactive agents with enhanced monitoring and predefined stop rules [40,66,67]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Dose thresholds and stability criteria defined; MD and RN confirm before session. | Mobilization performed on norepinephrine ≤ 0.1 µg/kg/min with continuous monitoring. | ||

| Line/tube security plan (ETT/tracheostomy, central/arterial lines, drains) agreed before mobilization [42,68,69,70]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | RN secures lines; RT manages airway; PT leads movement plan. | All lines secured; RT present for ETT; PT leads transfer to chair. | |

| Pre-session screen covers oxygenation (FiO2/SpO2/PEEP), hemodynamics (HR/MAP), sedation/delirium, and line security [31,46,69,70]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Team confirms parameters within acceptable ranges before starting. | Pre-session screen met: FiO2 ≤ 0.6, PEEP ≤ 10 cmH2O, MAP ≥ 65 mmHg. | |

| In-session monitoring of SpO2, HR, BP, cardiac rhythm, and symptoms (dyspnea/Borg) [36,42,46,49]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Telemetry/oximetry continuous; RT monitors ventilator parameters. | SpO2 and HR monitored continuously; Borg recorded each bout. | ||

| Terminate for hypoxemia/desaturation, arrhythmia, hypotension, neurologic change, or line compromise [36,40,44,46]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Predefined thresholds and response plan documented. | Session stopped for SpO2 < 88% or ↓ ≥4% from baseline; reassess and resume when stable. | |

| EMR records the provider, activity level (e.g., IMS), planned vs. delivered dose, and adverse events [40,42,43,70]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Standardized fields support audit and billing readiness. | PT: IMS = 6 (standing), planned 2 × 10 sit-to-stand; delivered 2 × 8; no adverse events. | ||

| Daily ICU mobility rounds include PT; goals updated and barriers addressed [32,37,43,68]. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Shared dashboard with unit indicators reviewed weekly/monthly. | Mobility goal updated to walk 10 m with assistive device; suction equipment arranged. |

| Assessment/Outcome | Construct and Scoring | Common Measurement Time Points Observed | Interpretation and MCID/MDC | Administration and Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU Mobility Scale [35,36,38,40,41,62,65] | Eleven levels (0–10), higher = better; zero passive in-bed → ten independent ambulation. | ICU first feasible; daily; ICU discharge; sometimes hospital discharge or 30–90 day follow-up. | Higher = better; MCID/MDC not established in included studies. | PT/OT; ~1–2 min; no equipment; record highest level achieved; monitor SpO2/HR/BP per safety table. |

| Functional Status Score for the ICU [35,36,38,40,62,71] | Five mobility tasks (roll, transfer supine ↔ sit, sit ↔ stand, sit, walk); each 0–7; total 0–35, higher = better. | ICU first feasible; ICU discharge; often hospital discharge; sometimes 30–90-day follow-up. | Higher = better; MCID/MDC not established in included studies. | PT/OT; ~5–7 min; bed/chair, gait belt; monitor SpO2/HR/BP per safety table. |

| Medical Research Council sum score [31,40,53,55,62,70,72] | Six bilateral muscle groups 0–5; total 0–60, higher = better. | ICU first feasible; ICU discharge; often hospital discharge; sometimes 30–90-day follow-up. | Higher = better; MCID/MDC not established in included studies. | PT/OT; ~5–10 min; standardized positions; avoid excessive resistance if unstable; monitor per safety table. |

| Physical Function in ICU Test scored [40,62,64,71] | Sit-to-stand assistance 0–3, marching cadence 0–3, shoulder/knee strength 0–2; total 0–10, higher = better. | ICU first feasible; ICU discharge; occasionally hospital discharge or 30–90-day follow-up. | Higher = better; MCID/MDC not established in included studies. | PT/OT; ~5–7 min; chair, stopwatch/metronome for cadence; monitor per safety table. |

| 6-Minute Walk Test [31,69,73] | Distance walked in 6 min (m); higher = better. | Hospital discharge or post-ICU follow-up when feasible. | MCID/MDC not established in included ICU studies; increase in meters indicates improvement. | PT/OT; measured corridor ~30 m; standardized protocol; monitor per safety table. |

| Other clinical outcomes (LOS, ventilator days, discharge destination, mortality) [36,37,38,40,42,62,65,71,74,75,76,77] | Service/clinical outcomes from EMR: ICU/hospital LOS (days), ventilator days, discharge destination, ICU/in-hospital mortality. | ICU discharge and hospital discharge; mortality also in-ICU/in-hospital and sometimes 30–90-day follow-up. | MCID/MDC not established; better outcomes correspond to fewer days, lower mortality, and discharge to home or inpatient rehabilitation. | Extract from EMR with predefined windows and definitions; note censoring and competing risks; align with safety table where relevant. |

| Parameters | Readiness Screen with Pass or Hold Cues | Typical Progression Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| In-bed therapeutic exercise (active/active-assisted) [37,38,78,79] | Stable oxygenation/hemodynamics; follows simple commands or assisted participation | Reps ↑ → task complexity ↑ → add light resistance → transition to EOB tasks |

| Sitting at EOB [32,35,36,37,38] | Orthostatic tolerance acceptable; lines secured; path clear | Duration ↑ → support ↓ → add balance tasks → prepare sit-to-stand |

| Sit-to-stand/static standing [32,33,37,40,42] | Orthostatic tolerance; lines secured; team spotter available | Assistance level ↓ → reps/stand time ↑ → add marching/weight-shift |

| Bed-to-chair transfer [32,36,37,42] | Stable oxygenation/hemodynamics; chair locked; airway/lines plan complete | Assistance level ↓ → transfer type advance (slide/pivot → stand-step) → rest ↓ |

| Ambulation/gait [32,37,40,42,62,80] | Orthostatic tolerance; portable monitoring; lines secured with slack | Distance ↑ → pace ↑ → device support ↓ → dual-task/turns ↑ |

| Task-specific functional training [36,37,38,46] | Commands followed; path clear; equipment ready | Repetitions/time ↑ → assistance ↓ → integrate standing/stepping → add dual-task |

| In-bed cycle ergometry (lower limbs) [50,81] | Stable oxygenation/hemodynamics; ventilator tolerated; lines secured | Assisted → active time ↑ → resistance/gear ↑ → rest intervals ↓ |

| Upper-limb ergometer [31,49,67,69] | Stable SpO2/MAP; light sedation (RASS −2 to 0); line slack verified | Duration ↑ → cadence/resistance ↑ → assistance ↓ |

| Bedside treadmill/body-weight support treadmill [51] | Harness fitted; team ready; orthostatic tolerance; device alarms tested | %body-weight support ↓ → speed/time ↑ → transition to overground |

| Robotic- or suspension-assisted [53,54] | Device compatibility; trained staff; airway/lines secured | Assistance/support ↓ → stepping duration/complexity ↑ → integrate conventional tasks |

| Safety Domain | Pre-Session Screen | In-Session Monitoring | Stop Rules with Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygenation (FiO2/SpO2) [36,40,42,46,49,50] | FiO2 ≤ 0.6; SpO2 ≥ 90% *; no acute distress; lines secured. | SpO2 continuous; dyspnea/fatigue queried; pace/time adjusted as tolerated. | SpO2 < 88–90% or symptomatic drop → stop, seated rest, return to prior level, raise O2 per protocol, notify. |

| Ventilation setting (PEEP) [36,40,42,46,50,65] | PEEP ≤ 10–12; ventilator tolerated; airway secure; team ready. | Observe ventilator synchrony; RR/work of breathing checked. | Loss of synchrony or distress → stop, rest, reposition airway/lines, prior level on resumption. |

| Hemodynamics (MAP/HR) [36,40,42,65,66,82] | MAP ≥ 65 mmHg; no unstable arrhythmia; low-dose vasoactive permitted with enhanced monitoring. | HR/BP rhythm observed; symptoms queried. | MAP < 65 or symptomatic tachy/brady/arrhythmia → stop, seated rest, prior level on resumption, notify. |

| Sedation/Delirium (RASS/CAM-ICU) [36,46,68,69,83] | RASS −2~0; follows simple commands; CAM-ICU documented. | Arousal maintained; attention/behavior observed. | Agitation or reduced arousal → stop, calm environment, resume at lower level when stable. |

| Lines/tubes security [36,40,42,50,65,67] | Access/airway/drains secured; route cleared; device check complete. | Line slack and fixation rechecked at transitions. | Line/device traction, leak, alarm → stop, secure/replace, reassess before resuming. |

| In-session monitoring [36,42,46,49,50,65] | Monitors available; baseline recorded; team roles confirmed. | SpO2/HR/BP/ECG as available; Borg/symptoms every few minutes. | Any predefined trigger → stop, document event, revert to prior level, inform team. |

| Stop rules (composite) [36,42,46,49,50,65,66,67] | Thresholds known to team; documentation ready. | Triggers watched: hypoxemia, hemodynamic instability, device issues, neurologic change, and patient request. | Trigger → immediate stop, safety first, document type/severity/action, plan modified on restart. |

| EMR Field | Definition/Examples | Field Format | Documentation Timing | Quality Rule/Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider and team attendance [36,40,42,65,67,84] | PT identifier; co-attendance by RN/RT/MD recorded. | PT name/initials; multi-select for attendees; required. | Per session; confirm pre-session; final check at session end. | PT presence required; mismatch with orders flagged. |

| Date/time and session duration [36,42,49,50,68] | Clock start–stop times; total minutes. | Datetime start; datetime end; auto-calculated duration. | Completed at session end. | Start < end; duration > 0; extreme values flagged. |

| Pre-session safety parameters (FiO2/SpO2/PEEP/MAP/RASS) [36,42,50,65,67] | Baseline values recorded immediately before activity: FiO2, SpO2, PEEP, MAP, and RASS. | Numeric (FiO2, SpO2, PEEP, MAP); ordinal (RASS). Units/scale displayed in field labels. | Within 15 min pre-session. | Outside thresholds requires rationale; missing values flagged |

| Activity level (IMS or equivalent) and assistance/device used [33,36,42,62,67,70] | Highest level achieved; assistance grade; device used. | IMS 0–10; assistance level; device list; distance/steps. | At session end. | Internal consistency check (level vs. assistance/device) |

| Planned vs. delivered dose and progression criteria [36,37,49,50] | Intended vs. delivered frequency/intensity/time; progression applied. | Planned fields; delivered fields; yes/no progression; reason if no. | During session and at session end | Variance >20% requires reason; progression aligned with safety rules. |

| In-session monitoring and patient-reported symptoms [36,42,49,50] | SpO2/HR/BP readings; dyspnea/fatigue/pain ratings. | Numeric time-stamped entries; Borg 0–10; pain 0–10 | Baseline, peak, end. | Predefined triggers documented with action; missing intervals flagged. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive care units |

| PT | Physical Therapists |

| OT | Occupational Therapists |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| FITT | Frequency/Intensity/Type/Time |

| IMS | ICU Mobility Scale |

| FSS-ICU | Functional Status Score for the ICU |

| MRC | Medical Research Council |

| EMR | Electrical Medical Record |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| EOB | Edge of the bed |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| OOB | Out of bed |

| SpO2 | Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation |

| RASS | Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale |

| ADL | Activities of daily living |

| PFIT | Physical Function ICU Test |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| RPM | Repetitions per Minute |

| CPM | Continuous passive movement |

| BSWT | Body-weight support treadmill |

| NMES | Neuromuscular electrical stimulation |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| FiO2 | Fraction of Inspired Oxygen |

| PEEP | Positive End-Expiratory Pressure |

| MAP | Mean Arterial Pressure |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

| MD | Medical Doctor |

| RT | Respiratory Therapist |

| ETT | Endotracheal Tube |

| 6MWT | 6-Minute Walk Test |

| MCID | Minimal clinically important difference |

| MDC | Minimally detectable change |

| RR | Respiration Rate |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| CAM-ICU | Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

References

- Devlin, J.W.; Skrobik, Y.; Gélinas, C.; Needham, D.M.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Watson, P.L.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; Rochwerg, B.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K.; Balas, M.C.; Stollings, J.L.; McNett, M.; Girard, T.D.; Chanques, G.; Kho, M.E.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Brummel, N.E.; et al. A Focused Update to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Anxiety, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 53, e711–e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummel, N.E.; Girard, T.D.; Ely, E.W.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Morandi, A.; Hughes, C.G.; Graves, A.J.; Shintani, A.; Murphy, E.; Work, B.; et al. Feasibility and Safety of Early Combined Cognitive and Physical Therapy for Critically Ill Medical and Surgical Patients: The Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) Trial. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertschi, D.; Rotondo, F.; Waskowski, J.; Venetz, P.; Pfortmueller, C.A.; Schefold, J.C. Post-Extubation Dysphagia in the ICU−a Narrative Review: Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Clinical Management (Update 2025). Crit. Care 2025, 29, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, P.E.; Goad, A.; Thompson, C.; Taylor, K.; Harry, B.; Passmore, L.; Ross, A.; Anderson, L.; Baker, S.; Sanchez, M.; et al. Early Intensive Care Unit Mobility Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Failure. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, H.J.; Needham, D.M.; Morris, P.E.; Gropper, M.A. ICU Early Mobilization: From Recommendation to Implementation at Three Medical Centers. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, S69–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.K.; Paykel, M.S.; Haines, K.J.; Hodgson, C.L. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Early Mobilization in the ICU: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e1121–e1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweickert, W.D.; Pohlman, M.C.; Pohlman, A.S.; Nigos, C.; Pawlik, A.J.; Esbrook, C.L.; Spears, L.; Miller, M.; Franczyk, M.; Deprizio, D.; et al. Early Physical and Occupational Therapy in Mechanically Ventilated, Critically Ill Patients: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2009, 373, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, X. Active Mobilization for Mechanically Ventilated Patients: A Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEAM Study Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group; Hodgson, C.L.; Bailey, M.; Bellomo, R.; Brickell, K.; Broadley, T.; Buhr, H.; Gabbe, B.J.; Gould, D.W.; Harrold, M.; et al. Early Active Mobilization during Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1747–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, K.; Lin, F.; Chaboyer, W.; Ranse, K.; Heffernan, A.; Mitchell, M. The Effect of the ABCDE/ABCDEF Bundle on Delirium, Functional Outcomes, and Quality of Life in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 138, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, C.L.; Stiller, K.; Needham, D.M.; Tipping, C.J.; Harrold, M.; Baldwin, C.E.; Bradley, S.; Berney, S.; Caruana, L.R.; Elliott, D.; et al. Expert Consensus and Recommendations on Safety Criteria for Active Mobilization of Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Adults. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 2014, 18, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, M.; Chan, S.; Neto, A.S.; Tipping, C.J.; Stratton, A.; Lane, R.; Romero, L.; Broadley, T.; Hodgson, C.L. Association of Active Mobilisation Variables with Adverse Events and Mortality in Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, K.P.; Joseph-Isang, E.; Robinson, L.E.; Parry, S.M.; Morris, P.E.; Neyra, J.A. Safety and Feasibility of Physical Rehabilitation and Active Mobilization in Patients Requiring Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e1112–e1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrinc, G.; Davies, L.; Goodman, D.; Batalden, P.; Davidoff, F.; Stevens, D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H.; Ko, R.-E.; Kang, D.; Park, J.; Jeon, K.; Yang, J.H.; Park, C.-M.; Cho, J.; Park, Y.S.; Park, H.; et al. Relationship between Use of Rehabilitation Resources and ICU Readmission and ER Visits in ICU Survivors: The Korean ICU National Data Study 2008-2015. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.H.; Friedman, M.; Hoyer, E.H.; Kudchadkar, S.; Flanagan, E.; Klein, L.; Daley, K.; Lavezza, A.; Schechter, N.; Young, D. The Johns Hopkins Activity and Mobility Promotion Program. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2023, 38, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, C.L.; Lieu, B.K.; Caldwell, E.S. Manual Muscle Strength Testing of Critically Ill Patients: Feasibility and Interobserver Agreement. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, C.; Needham, D.; Haines, K.; Bailey, M.; Ward, A.; Harrold, M.; Young, P.; Zanni, J.; Buhr, H.; Higgins, A.; et al. Feasibility and Inter-Rater Reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung 2014, 43, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipping, C.J.; Bailey, M.J.; Bellomo, R.; Berney, S.; Buhr, H.; Denehy, L.; Harrold, M.; Holland, A.; Higgins, A.M.; Iwashyna, T.J.; et al. The ICU Mobility Scale Has Construct and Predictive Validity and Is Responsive. A Multicenter Observational Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Chan, K.S.; Zanni, J.M.; Parry, S.M.; Neto, S.-C.G.B.; Neto, J.A.A.; da Silva, V.Z.M.; Kho, M.E.; Needham, D.M. Functional Status Score for the ICU: An International Clinimetric Analysis of Validity, Responsiveness, and Minimal Important Difference. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, e1155–e1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhorebeek, I.; Latronico, N.; Van den Berghe, G. ICU-Acquired Weakness. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.B.; Nollet, J.L.; Spronk, P.E.; González-Fernández, M. Prevalence, Pathophysiology, Diagnostic Modalities, and Treatment Options for Dysphagia in Critically Ill Patients. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceição, T.M.A.; Gonzáles, A.I.; de Figueiredo, F.C.X.S.; Vieira, D.S.R.; Bündchen, D.C. Safety criteria to start early mobilization in intensive care units. Systematic review. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva 2017, 29, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An Extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martí, J.D.; McWilliams, D.; Gimeno-Santos, E. Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, P.; Gupta, P.; Shiju, S.; Omar, A.S.; Ansari, S.; Mathew, G.; Varghese, M.; Pulimoottil, J.; Varkey, S.; Mahinay, M.; et al. Multidisciplinary, Early Mobility Approach to Enhance Functional Independence in Patients Admitted to a Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit: A Quality Improvement Programme. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, G.; Kanayama, H.; Arai, Y.; Iwanami, Y.; Kobori, T.; Masuyama, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Serizawa, H.; Nakamichi, Y.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Early Mobilization Using a Mobile Patient Lift in the ICU: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 52, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viloria, M.A.D.; Lee, S.-D.; Takahashi, T.; Cheng, Y.-J. Physical Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit: A Cross-Sectional Study of Three Asian Countries. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, S.E.; Rodrigues, M.K.; Oliveira, M.F.; Tanaka, C. Timing to Out-of-Bed Mobilization and Mobility Levels of COVID-19 Patients Admitted to the ICU: Experiences in Brazilian Clinical Practice. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2024, 40, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Tsang, J.H.C.; Cheung, E.; Chan, W.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Lui, S.R.; Lee, C.Y.; Lee, A.L.H.; Lam, P.K.N. Improving Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit with a Protocolized, Early Mobilization Program: Observations of a Single Center before-and-after the Implementation of a Multidisciplinary Program. Acute Crit. Care 2022, 37, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, S.; Anstey, M.; Blobner, M.; Edrich, T.; Grabitz, S.; Gradwohl-Matis, I.; Heim, M.; Houle, T.; Kurth, T.; Latronico, N.; et al. Early, Goal-Directed Mobilisation in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 1377–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, D.; Snelson, C.; Goddard, H.; Attwood, B. Introducing Early and Structured Rehabilitation in Critical Care: A Quality Improvement Project. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 53, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, M.A.S.; Carvalho, E.V.; de Souza Vieira, R.; Bastos-Netto, C.; de Jesus, L.A.D.S.; Stohler, C.G.; Arantes, G.C.; Colugnati, F.A.B.; Reboredo, M.M.; Pinheiro, B.V. Effect of a Structured Early Mobilization Protocol on the Level of Mobilization and Muscle Strength in Critical Care Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2024, 40, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundadottir, O.R.; Jónasdóttir, R.J.; Sigvaldason, K.; Gunnsteinsdottir, E.; Haraldsdottir, B.; Sveinsson, T.; Sigurdsson, G.H.; Dean, E. Effects of Intensive Upright Mobilisation on Outcomes of Mechanically Ventilated Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: A Randomised Controlled Trial with 12-Months Follow-Up. Eur. J. Physiother. 2021, 23, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schujmann, D.S.; Lunardi, A.C.; Fu, C. Progressive Mobility Program and Technology to Increase the Level of Physical Activity and Its Benefits in Respiratory, Muscular System, and Functionality of ICU Patients: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2018, 19, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasano, N.; Kato, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Kusama, N. Out-of-the-ICU Mobilization in Critically Ill Patients: The Safety of a New Model of Rehabilitation. Crit. Care Explor. 2022, 4, e0604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, C.A.; Chapman, L.B.; Berger, L.J.; Kelly, T.L.; Korpela, C.A.; Petty, M.G. Early Mobilization in the ICU: A Collaborative, Integrated Approach. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, H.; Aubreton, S.; Vallat, A.; Pereira, B.; Souweine, B.; Constantin, J.-M.; Coudeyre, E. Very Early Exercise Tailored by Decisional Algorithm Helps Relieve Discomfort in ICU Patients: An Open-Label Pilot Study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrigle, L.; Caunt, J. Physical Therapist-Led Ambulatory Rehabilitation for Patients Receiving CentriMag Short-Term Ventricular Assist Device Support: Retrospective Case Series. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummel, N.; Jackson, J.; Girard, T.; Pandharipande, P.; Schiro, E.; Work, B.; Pun, B.; Boehm, L.; Gill, T.; Ely, E. A Combined Early Cognitive and Physical Rehabilitation Program for People Who Are Critically Ill: The Activity and Cognitive Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit (ACT-ICU) Trial. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 1580–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, K.; Troeller, H.; Panter, S.; Winter, E.; Patel, J.J. Overview of Intensive Care Unit-Related Physical and Functional Impairments and Rehabilitation-Related Devices. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2018, 33, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weblin, J.; Harriman, A.; Butler, K.; Snelson, C.; McWilliams, D. Comparing Rehabilitation Outcomes for Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit with COVID-19 Requiring Mechanical Ventilation during the First Two Waves of the Pandemic: A Service Evaluation. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 75, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirakawa, K.; Nakayama, A.; Arimitsu, T.; Kon, K.; Ueki, H.; Hori, K.; Ishimoto, Y.; Ogawa, A.; Higuchi, R.; Hosoya, Y.; et al. Feasibility and Safety of Upper Limb Extremity Ergometer Exercise in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit in Critically Ill Patients with Cardiac Disease: A Prospective Observational Study. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1448647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimawi, I.; Lamberjack, B.; Nelliot, A.; Toonstra, A.L.; Zanni, J.; Huang, M.; Mantheiy, E.; Kho, M.E.; Needham, D.M. Safety and Feasibility of a Protocolized Approach to In-Bed Cycling Exercise in the Intensive Care Unit: Quality Improvement Project. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, J.; Wieferink, D.C.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Nollet, F.; Engelbert, R.H.H.; van der Schaaf, M. Body Weight-Supported Bedside Treadmill Training Facilitates Ambulation in ICU Patients: An Interventional Proof of Concept Study. J. Crit. Care 2017, 41, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakman, R.C.H.; Voorn, E.L.; Horn, J.; Nollet, F.; Engelbert, R.H.H.; Sommers, J.; van der Schaaf, M. Steps to Recovery: Body Weight-Supported Treadmill Training for Critically Ill Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Crit. Care 2022, 69, 154000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M.; Baum, F.; Kloss, P.; Langer, N.; Arsene, V.; Warner, L.; Panelli, A.; Hartmann, F.V.; Fuest, K.; Grunow, J.J.; et al. Robotic-Assisted In-Bed Mobilization in Ventilated ICU Patients With COVID-19: An Interventional, Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study (ROBEM II Study). Crit. Care Med. 2024, 52, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wu, H.; Huang, X.; Song, J.; Fang, F. Early Efficacy Observation of Suspended Lower-Limb Rehabilitation Robot-Assisted Therapy in Patients with Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness: A Study Protocol for a Self-Controlled Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, F.V.; Cipriano, G.J.; Vieira, L.; Güntzel Chiappa, A.M.; Cipriano, G.B.F.; Vieira, P.; Zago, J.G.; Castilhos, M.; da Silva, M.L.; Chiappa, G.R. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Combined with Exercise Decreases Duration of Mechanical Ventilation in ICU Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 36, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Chen, K.; Ma, Z.; Bai, Y.; Xu, Y. Prevention of Muscle Atrophy in ICU Patients without Nerve Injury by Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation: A Randomized Controlled Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S.; Elbiaa, M.; Mansour, E.; El-Menshawy, A.; Elsayed, S. Effect of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation and Early Physical Activity on ICU-Acquired Weakness in Mechanically Ventilated Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nurs. Crit. Care 2024, 29, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akar, O.; Günay, E.; Sarinc Ulasli, S.; Ulasli, A.M.; Kacar, E.; Sariaydin, M.; Solak, Ö.; Celik, S.; Ünlü, M. Efficacy of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in Patients with COPD Followed in Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Respir. J. 2017, 11, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsaki, I.; Gerovasili, V.; Sidiras, G.; Karatzanos, E.; Mitsiou, G.; Papadopoulos, E.; Christakou, A.; Routsi, C.; Kotanidou, A.; Nanas, S. Effect of Neuromuscular Stimulation and Individualized Rehabilitation on Muscle Strength in Intensive Care Unit Survivors: A Randomized Trial. J. Crit. Care 2017, 40, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, C.; Jia, Y.; Xiao, Q. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Assisted Active Limb Movement Exercises for Patients in the Respiratory Intensive Care Unit: A Randomized Pilot Study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 57, jrm28399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummel, N.; Jackson, J.; Girard, T.; Pandharipande, P.; Boehm, L.; Okahashi, J.; Strength, C.; Schiro, E.; Work, B.; Pun, B.; et al. Feasibility of an Early Physical and Cognitive Rehabilitation Protocol for Critically Ill Patients: The Activity and Cognitive Therapy in the ICU (ACT-ICU) Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, A3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, C.L.; Bailey, M.; Bellomo, R.; Berney, S.; Buhr, H.; Denehy, L.; Gabbe, B.; Harrold, M.; Higgins, A.; Iwashyna, T.J.; et al. A Binational Multicenter Pilot Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial of Early Goal-Directed Mobilization in the ICU. Crit. CARE Med. 2016, 44, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, C.; Haines, K.J.; Francis, J.J.; Marshall, A.; O’Connor, D.; Skinner, E.H. Mobilization of Ventilated Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: An Elicitation Study Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Crit. CARE 2015, 30, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadyanemhandu, C.; Manie, S. Implementation of the Physical Function ICU Test Tool in a Resource Constrained Intensive Care Unit to Promote Early Mobilisation of Critically Ill Patients—A Feasibility Study. Arch. Physiother. 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nydahl, P.; Günther, U.; Diers, A.; Hesse, S.; Kerschensteiner, C.; Klarmann, S.; Borzikowsky, C.; Köpke, S. PROtocol-Based MObilizaTION on Intensive Care Units: Stepped-Wedge, Cluster-Randomized Pilot Study (Pro-Motion). Nurs. Crit. Care 2020, 25, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsukawa, H.; Ota, K.; Liu, K.; Morita, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Sato, K.; Ishii, K.; Yasumura, D.; Takahashi, Y.; Tani, T.; et al. Risk Factors of Patient-Related Safety Events during Active Mobilization for Intubated Patients in Intensive Care Units-A Multi-Center Retrospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.; Paratz, J.; Tronstad, O.; Caruana, L.; Walsh, J. Exercise Is Feasible in Patients Receiving Vasoactive Medication in a Cardiac Surgical Intensive Care Unit: A Prospective Observational Study. Aust. Crit. Care 2020, 33, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, S.M.; Nydahl, P.; Needham, D.M. Implementing Early Physical Rehabilitation and Mobilisation in the ICU: Institutional, Clinician, and Patient Considerations. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.D.; Nelliot, A.; Needham, D.M. Early Mobilization and Rehabilitation in the ICU: Moving Back to the Future. Respir. Care 2016, 61, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalon, M.X.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Posner, E.; Spielman, L.; Delgado, A.; Kolakowsky-Hayner, S.A. The Effects of Early Mobilization on Patients Requiring Extended Mechanical Ventilation Across Multiple ICUs. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravankumar, J.; Paramaswamy, R.; Annadurai, B.; Iswarya, S.; Santhana Lakshmi, S.; Vishnuram, S.; Jeslin, G.N.; Sundaram Subramanian, S.; Senthilkumar, N. Effect of Early Mobilization on Functional Recovery in ICU Patients with Post-COVID ARDS. Fizjoterapia Pol. 2024, 24, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Taniuchi, K.; Karasawa, T.; Matsui, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Ikegami, S.; Imamura, H.; Horiuchi, H. The Impact of Early Mobilization on the Incidence of Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness in Patients with Sepsis in the Critical Care-The Shinshu Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study (EROSCCS Study). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B.; Thompson, A.; Douiri, A.; Moxham, J.; Hart, N. Exercise-Based Rehabilitation after Hospital Discharge for Survivors of Critical Illness with Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness: A Pilot Feasibility Trial. J. Crit. Care 2015, 30, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Geng, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Lan, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Effect of Early Mobilization on the Development of Pneumonia in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury in the Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit: A Historical Controls Study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2024, 29, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Mi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Gan, R.; Mu, S. Effects of the High-Intensity Early Mobilization on Long-Term Functional Status of Patients with Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 4118896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, A.G.; Prabhu, N.S.; Jirange, P.; Kamath, A.; Vaishali, K. Quality of Life Improves with Individualized Home-Based Exercises in Critical Care Survivors. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 21, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Henning, A.N.; Morris, P.E.; Tezanos, A.G.V.; Dupont-Versteegden, E.E. Timing and Amount of Physical Therapy Treatment Are Associated with Length of Stay in the Cardiothoracic ICU. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, M.A.; Aziz, A.R.; Rahiminezhad, E.; Dehghan, M. Effectiveness of Massage and Range of Motion Exercises on Muscle Strength and Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness in Iranian Patients with COVID-19: A Randomized Parallel-Controlled Trial. Acute Crit. Care 2024, 39, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos Biazon, T.M.P.; Libardi, C.A.; Junior, J.C.B.; Caruso, F.R.; da Silva Destro, T.R.; Molina, N.G.; Borghi-Silva, A.; Mendes, R.G. The Effect of Passive Mobilization Associated with Blood Flow Restriction and Combined with Electrical Stimulation on Cardiorespiratory Safety, Neuromuscular Adaptations, Physical Function, and Quality of Life in Comatose Patients in an ICU: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Trials 2021, 22, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Tsuchiya, A.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Okawa, T.; Kubo, D.; Horimizu, Y.; Tsutsui, R.; Shukumine, H.; Noda, K.; Mizuno, K. Effect of a Generalized Early Mobilization and Rehabilitation Protocol on Outcomes in Trauma Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Pre–Post Study. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, J.; Van den Boorn, M.; Engelbert, R.H.H.; Nollet, F.; Van der Schaaf, M.; Horn, J. Feasibility of Muscle Activity Assessment With Surface Electromyography During Bed Cycling Exercise In Intensive Care Unit Patients. Muscle Nerve 2018, 58, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickels, M.R.; Blythe, R.; White, N.; Ali, A.; Aitken, L.M.; Heyland, D.K.; McPhail, S.M. Predictors of Acute Muscle Loss in the Intensive Care Unit: A Secondary Analysis of an in-Bed Cycling Trial for Critically Ill Patients. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garegnani, L.; Ivaldi, D.; Burgos, M.A.; Varela, L.B.; Díaz Menai, S.; Rico, S.; Giménez, M.L.; Escobar Liquitay, C.M.; Franco, J.V. Exercise Therapy for the Treatment of Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 8, CD015830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischmeyer, P.E.; Puthucheary, Z.; San Millán, I.; Butz, D.; Grocott, M.P.W. Muscle Mass and Physical Recovery in ICU: Innovations for Targeting of Nutrition and Exercise. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2017, 23, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsees, J.; Moore, Z.; Patton, D.; Watson, C.; Nugent, L.; Avsar, P.; O’Connor, T. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Early Mobilisation on Length of Stay for Adults in the Intensive Care Unit. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, A.; Yoshihiro, S.; Shida, H.; Aikawa, G.; Fujinami, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Nakanishi, N.; Shimizu, M.; Watanabe, S.; Sugimoto, K.; et al. Effects of Mobilization within 72 h of ICU Admission in Critically Ill Patients: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, M.; Fuest, K.; Ulm, B.; Grunow, J.J.; Warner, L.; Bald, A.; Arsene, V.; Verfuß, M.; Daum, N.; Blobner, M.; et al. The Optimal Dose of Mobilisation Therapy in the ICU: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Intensive Care 2023, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, S.J.; Scheffenbichler, F.T.; Bein, T.; Blobner, M.; Grunow, J.J.; Hamsen, U.; Hermes, C.; Kaltwasser, A.; Lewald, H.; Nydahl, P.; et al. Guideline on Positioning and Early Mobilisation in the Critically Ill by an Expert Panel. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrush, A.; Steenbergen, E. Clinical Properties of the 6-Clicks and Functional Status Score for the ICU in a Hospital in the United Arab Emirates. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 2404–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, N.E.; Zerfas, I.; Wong, A.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Smithburger, P.L.; Buckley, M.S.; Devlin, J.W.; Kane-Gill, S.L. Clinical Impact of the Implementation Strategies Used to Apply the 2013 Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium or 2018 Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, Sleep Disruption Guideline Recommendations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 52, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, S.; Doroy, A.; Da Marto, N.; Taylor, S.; Anderson, N.; Young, H.M.; Adams, J.Y. Quantifying Mobility in the ICU: Comparison of Electronic Health Record Documentation and Accelerometer-Based Sensors to Clinician-Annotated Video. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipping, C.J.; Holland, A.E.; Harrold, M.; Crawford, T.; Halliburton, N.; Hodgson, C.L. The Minimal Important Difference of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung 2018, 47, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denehy, L.; de Morton, N.; Skinner, E.; Edbrooke, L.; Haines, K.; Warrillow, S.; Berney, S. A Physical Function Test for Use in the Intensive Care Unit: Validity, Responsiveness, and Predictive Utility of the Physical Function ICU Test (Scored). Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1636–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, E.J.; Soni, N.; Handy, J.M.; Brett, S.J. Construct Validity of the Chelsea Critical Care Physical Assessment Tool: An Observational Study of Recovery from Critical Illness. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 2014, 18, R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenji Nawa, R.; Luiz Ferreira De Camillis, M.; Buttignol, M.; Machado Kutchak, F.; Chaves Pacheco, E.; Rodrigues Gonçalves, L.H.; Correa Garcia, L.M.; Tavares Timenetsky, K.; Forgiarini, L.A. Clinimetric Properties of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score—A Multicenter Study for Minimum Important Difference and Responsiveness Analysis. Colomb. Medica Cali Colomb. 2023, 54, e2005580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.J.; Sparbel, K.; Barr, R.N.; Doerschug, K.; Corbridge, S. Electronic Health Record Tool to Promote Team Communication and Early Patient Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit. Care Nurse 2018, 38, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, E.A.; Everard, T.; Holland, A.E.; Tipping, C.; Bradley, S.J.; Hodgson, C.L. Barriers and Facilitators to Early Mobilisation in Intensive Care: A Qualitative Study. Aust. Crit. Care 2015, 28, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennion, J.; Manning, C.; Mansell, S.K.; Garrett, R.; Martin, D. The Barriers to and Facilitators of Implementing Early Mobilisation for Patients with Delirium on Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2024, 25, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nydahl, P.; Sricharoenchai, T.; Chandra, S.; Kundt, F.S.; Huang, M.; Fischill, M.; Needham, D.M. Safety of Patient Mobilization and Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, B.T.; Balas, M.C.; Barnes-Daly, M.A.; Thompson, J.L.; Aldrich, J.M.; Barr, J.; Byrum, D.; Carson, S.S.; Devlin, J.W.; Engel, H.J.; et al. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambiaso-Daniel, J.; Parry, I.; Rivas, E.; Kemp-Offenberg, J.; Sen, S.; Rizzo, J.A.; Serghiou, M.A.; Kowalske, K.; Wolf, S.E.; Herndon, D.N.; et al. Strength and Cardiorespiratory Exercise Rehabilitation for Severely Burned Patients During Intensive Care Units: A Survey of Practice. J. Burn Care Res. 2018, 39, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferre, M.; Batista, E.; Solanas, A.; Martinez-Balleste, A. Smart Health-Enhanced Early Mobilisation in Intensive Care Units. Sensors 2021, 21, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickels, M.R.; Aitken, L.M.; Walsham, J.; Crampton, L.J.; Barnett, A.G.; McPhail, S.M. Exercise Interventions Are Delayed in Critically Ill Patients: A Cohort Study in an Australian Tertiary Intensive Care Unit. Physiotherapy 2020, 109, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korupolu, R.; Zanni, J.M.; Fan, E.; Butler, M.; Needham, D.M. Early Mobilisation of Intensive Care Unit Patient: The Challenges of Morbid Obesity and Multiorgan Failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2010, 2010, bcr0920092257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Johnson, L.; Lalonde, T. Early Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit: Standard Equipment vs a Mobility Platform. Am. J. Crit. Care 2014, 23, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, P.M.; Deshmukh, P.K. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers of Healthcare Providers toward Early Mobilization of Adult Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Unit. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, K. Physical Therapist-Led Therapeutic Exercise and Mobility in Adult Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review of Operational Definitions, Dose Progression, Safety, and Documentation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8948. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248948

Lee K. Physical Therapist-Led Therapeutic Exercise and Mobility in Adult Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review of Operational Definitions, Dose Progression, Safety, and Documentation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8948. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248948

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Kyeongbong. 2025. "Physical Therapist-Led Therapeutic Exercise and Mobility in Adult Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review of Operational Definitions, Dose Progression, Safety, and Documentation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8948. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248948

APA StyleLee, K. (2025). Physical Therapist-Led Therapeutic Exercise and Mobility in Adult Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review of Operational Definitions, Dose Progression, Safety, and Documentation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8948. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248948