Electric-Scooter- and Bicycle-Related Trauma in a Hungarian Level-1 Trauma Center—A Retrospective 1-Year Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

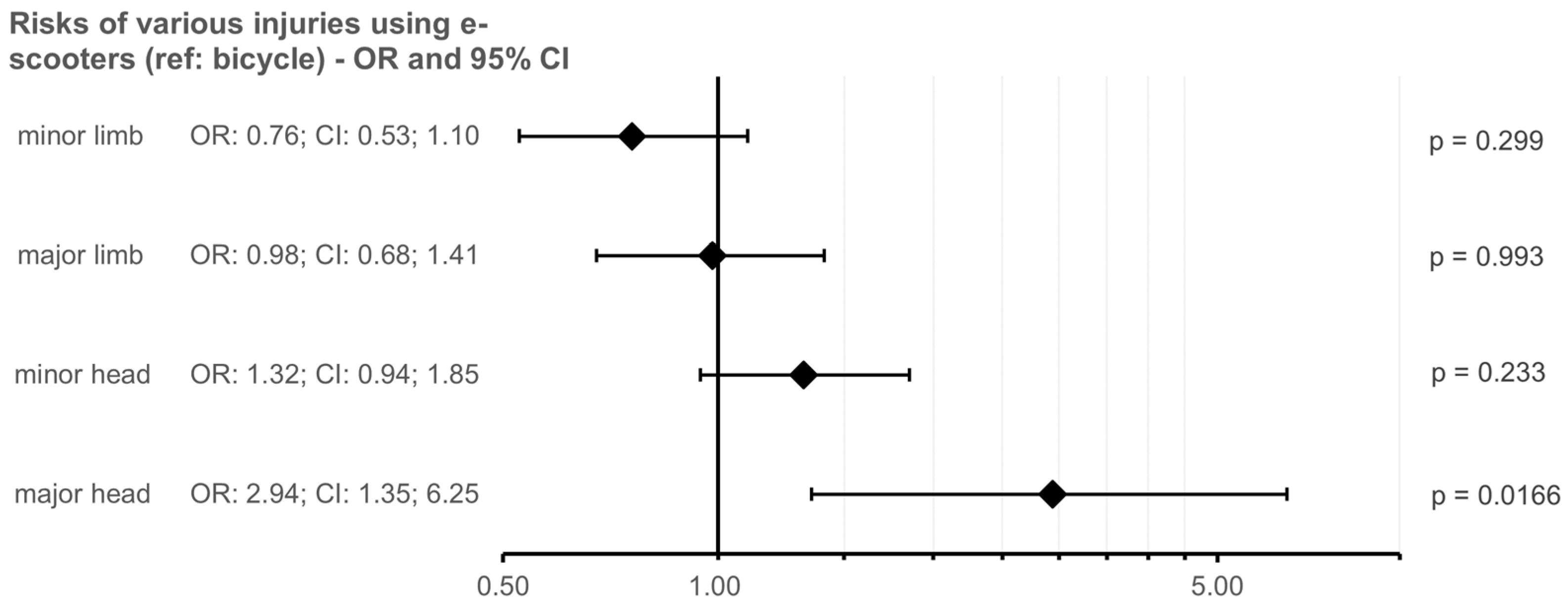

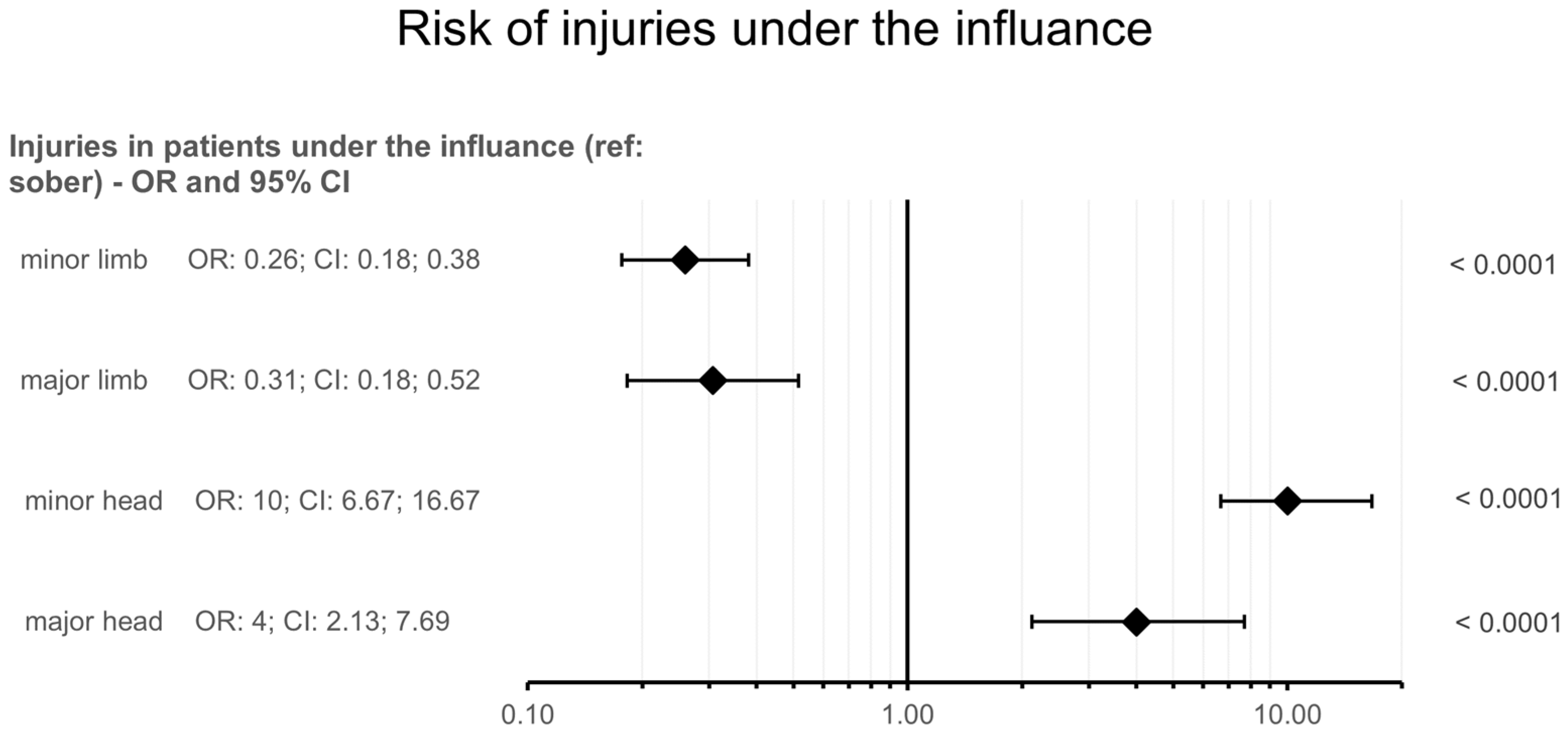

3. Results

In-Hospital Mortality, Surgery Rates, and GCS Distributions Across Head Injury Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lavoie-Gagne, O.; Siow, M.; Harkin, W.; Flores, A.R.; Girard, P.J.; Schwartz, A.K.; Kent, W.T. Characterization of electric scooter injuries over 27 months at an urban level 1 trauma center. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 45, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siow, M.Y.M.; Lavoie-Gagne, O.B.; Politzer, C.S.; Mitchell, B.C.; Harkin, W.E.B.; Flores, A.R.B.; Schwartz, A.K.; Girard, P.J.; Kent, W.T. Electric Scooter Orthopaedic Injury Demographics at an Urban Level I Trauma Center. J. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 34, e424–e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, B.S.; Elkbuli, A. Electric scooter-related injuries: The desperate need for regulation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 47, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moftakhar, T.; Wanzel, M.; Vojcsik, A.; Kralinger, F.; Mousavi, M.; Hajdu, S.; Aldrian, S.; Starlinger, J. Incidence and severity of electric scooter related injuries after introduction of an urban rental programme in Vienna: A retrospective multicentre study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinertz, H.; Ntalos, D.; Hennes, F.; Nüchtern, J.V.; Frosch, K.-H.; Thiesen, D.M. Accident Mechanisms and Injury Patterns in E-Scooter Users-A Retrospective Analysis and Comparison with Cyclists. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2021, 118, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Störmann, P.; Klug, A.; Nau, C.; Verboket, R.D.; Leiblein, M.; Müller, D.; Schweigkofler, U.; Hoffmann, R.; Marzi, I.; Lustenberger, T. Characteristics and Injury Patterns in Electric-Scooter Related Accidents-A Prospective Two-Center Report from Germany. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichman, I.; Shaked, O.; Factor, S.; Weiss-Meilik, A.; Khoury, A. Emergency department electric scooter injuries after the introduction of shared e-scooter services: A retrospective review of 3,331 cases. World J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 13, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffler, K.; Mancini, K.; Wilson, M.; Huang, A.; Mejia, E.; Yip, F.K. Intoxication is a Significant Risk Factor for Severe Craniomaxillofacial Injuries in Standing Electric Scooter Accidents. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, S.; Landschoof, S.; Kornherr, P.; Grospietsch, B.; Kuhne, C.A. Epidemiology and Injury Pattern of E-Scooter Injuries—Initial Results. [Verletzungen mit E-Scootern—Erste Ergebnisse zu Epidemiologie und Verletzungsmustern]. Z. Orthop. Unfall. 2022, 160, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishmael, C.R.; Hsiue, P.P.; Zoller, S.D.; Wang, P.; Hori, K.R.; Gatto, J.D.; Li, R.; Jeffcoat, D.M.; Johnson, E.E.; Bernthal, N.M. An Early Look at Operative Orthopaedic Injuries Associated with Electric Scooter Accidents: Bringing High-Energy Trauma to a Wider Audience. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2020, 102, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennocq, Q.; Schouman, T.; Khonsari, R.H.; Sigaux, N.; Descroix, V.; Bertolus, C.; Foy, J.-P. Evaluation of Electric Scooter Head and Neck Injuries in Paris, 2017–2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2026698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzani, Y.; Hai, D.B.; Cohen, N.; Drescher, M.J.; Chaushu, G.; Yahya, B.H. The impact of helmet use on oral and maxillofacial injuries associated with electric-powered bikes or powered scooter: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Head Face Med. 2021, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cittadini, F.; Aulino, G.; Petrucci, M.; Valentini, S.; Covino, M. Electric scooter-related accidents: A possible protective effect of helmet use on the head injury severity. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2023, 19, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloud, C.; Heß, S.; Kasinger, J. Do shared e-scooter services cause traffic accidents? Evidence from six European countries. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, H.; Yan, Z. Use of Mobile Sensing Data for Assessing Vibration Impact of E-Scooters with Different Wheel Sizes. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2023, 2677, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiri, N.K.; Lui, H.; Tangney, T.; Allen, I.E.; Cohen, A.J.; Breyer, B.N. Electric Scooter Injuries and Hospital Admissions in the United States, 2014–2018. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Feito, P.; Corominas, L.; Sánchez-Soler, J.F.; Pérez-Prieto, D.; Martínez-Diaz, S.; Alier, A.; Monllau, J.C. Electric Scooter-Related Injuries: A New Epidemic in Orthopedics. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhit, M.N.Z.; Le Fevre, J.; Bergin, C.J. Regional healthcare costs and burden of injury associated with electric scooters. Injury 2020, 51, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Wong, N.; Monk, P.; Munro, J.; Bahho, Z. The cost of electric-scooter related orthopaedic surgery. N. Z. Med. J. 2019, 132, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis, K.; Van Schagen, I. E-Scooters in Europe: Legal Status, Usage and Safety: Results of a Survey in FERSI Countries; FERSI: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://fersi.org/ (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Chrisafis, A. Rented E-Scooters Cleared from Paris Streets on Eve of Ban. The Guardian. 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/31/rented-e-scooters-cleared-from-paris-streets-on-eve-of-ban (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Zhang, X.; Cui, M.; Gu, Y.; Stallones, L.; Xiang, H. Trends in electric bike-related injury in China, 2004–2010. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, NP1819–NP1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.P.; O’Neill, B.; Haddon, W., Jr.; Long, W.B. The injury severity score: A method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J. Trauma 1974, 14, 187–196. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4814394 (accessed on 2 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Linn, S. The injury severity score--importance and uses. Ann. Epidemiol. 1995, 5, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Jami, M.; Geller, J.; Granger, C.; Geaney, L.; Aiyer, A. The impact of e-scooter injuries: A systematic review of 34 studies. Bone Jt. Open 2022, 3, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, M.B.; Noorzad, A.; Lin, C.; Little, M.; Lee, E.Y.; Margulies, D.R.; Torbati, S.S. Standing electric scooter injuries: Impact on a community. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownson, A.B.; Fagan, P.V.; Dickson, S.; Civil, I.D. Electric scooter injuries at Auckland City Hospital. N. Z. Med. J. 2019, 132, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cicchino, J.B.; Kulie, P.E.; McCarthy, M.L. Injuries related to electric scooter and bicycle use in a Washington, DC, emergency department. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2021, 22, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, S.N.F.; Rosenkrantz, O.C.M.; Lippert, F.; Christensen, H.C. Injury from electric scooters in Copenhagen: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e033988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, L.M.; Williams, E.; Brown, C.V.; Emigh, B.J.; Bansal, V.; Badiee, J.; Checchi, K.D.; Castillo, E.M.; Doucet, J. The e-merging e-pidemic of e-scooters. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2019, 4, e000337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinertz, H.; Volk, A.; Dalos, D.; Rutkowski, R.; Frosch, K.H.; Thiesen, D.M. Risk factors and injury patterns of e-scooter associated injuries in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, F.W.; Riis, C.; Janstrup, K.H.; Lin, H.; Huttel, F.B. Computer vision-based helmet use registration for e-scooter riders—The impact of the mandatory helmet law in Copenhagen. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 87, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guerre, L.E.V.M.; Sadiqi, S.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Oner, C.F.; van Gaalen, S.M. Injuries related to bicycle accidents: An epidemiological study in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 46, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.R.; Bazargan-Hejazi, S.; Shirazi, A.; Pan, D.; Lee, S.; Teruya, S.A.; Shaheen, M. Helmet use and bicycle-related trauma injury outcomes. Brain Inj. 2019, 33, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, M.J.; Tiong, Y.; Bhagvan, S. Shared electric scooter injuries admitted to Auckland City Hospital: A comparative review one year after their introduction. N. Z. Med. J. 2021, 134, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

| Bike (N = 1378) | Scooter (N = 190) | E-Scooter (N = 370) | Overall (N = 1938) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD *) | 38.5 (14.9) | 31.2 (13.7) | 31.9 (10.9) | 36.5 (14.4) |

| Sex—male | 954 (69.2%) | 112 (58.9%) | 245 (66.2%) | 1311 (67.6%) |

| Daytime—corrected * | ||||

| Morning | 114 (8.3%) | 17 (9.1%) | 25 (6.8%) | 157 (8.1%) |

| Daytime | 596 (43.3%) | 80 (41.9%) | 79 (21.2%) | 754 (38.9%) |

| Evening | 540 (39.2%) | 67 (35.0%) | 97 (26.3%) | 704 (36.3%) |

| Night | 127 (9.2%) | 27 (14.0%) | 169 (45.6%) | 322 (16.6%) |

| Alcohol consumption | 63 (4.6%) | 11 (5.8%) | 99 (26.8%) | 173 (8.9%) |

| Hospital admissions | 142 (10.3%) | 13 (6.8%) | 54 (14.6%) | 209 (10.8%) |

| Mean duration of stay in hospital (days) (SD) | 2.30 | 1.83 | 3.13 |

| Bike | Scooter | E-Scooter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sober (N = 1315) | Consumed Alcohol (N = 63) | Sober (N = 179) | Consumed Alcohol (N = 11) | Sober (N = 271) | Consumed Alcohol (N = 99) | |

| Mild limb | 1058 (80.5%) | 29 (46.0%) | 137 (76.5%) | 5 (45.5%) | 214 (79.0%) | 48 (48.5%) |

| Severe limb | 342 (26.0%) | 6 (9.5%) | 44 (24.6%) | 1 (9.1%) | 81 (29.9%) | 13 (13.1%) |

| Mild head | 361 (27.5%) | 51 (81.0%) | 61 (34.1%) | 9 (81.8%) | 99 (36.5%) | 89 (89.9%) |

| Severe head | 37 (2.8%) | 8 (12.7%) | 7 (3.9%) | 4 (36.4%) | 14 (5.2%) | 20 (20.2%) |

| Spinal injury | 57 (4.3%) | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mild body | 180 (13.7%) | 4 (6.3%) | 12 (6.7%) | 1 (9.1%) | 31 (11.4%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| Severe body | 29 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (2.2%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Type | N | GCS 15, n (%) | GCS 14, n (%) | GCS 13, n (%) | GCS 12, n (%) | GCS 10, n (%) | GCS 9, n (%) | Unknown GCS | In-Hospital Death, n (%) | Mean GCS ± SD | Surgery, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric-scooter-related head injury | Severe | 34 | 31 (91.17) | 2 (5.88) | 0(0.00) | 1 (2.94) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 14.85 ± 0.56 | 2 (5.88) |

| Mild | 188 | 182 (96.81) | 2 (1.06) | 1 (0.53) | 1 (0.53) | 1 (0.53) | 0(0.00) | 1 (0.53) | 0 (0.00) | 14.94 ± 0.46 | 9 (4.79) | |

| Bicycle-related head injury | Severe | 45 | 43 (95.56) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 1 (2.22) | 0(0.00) | 1 (2.22) | 0(0.00) | 2 (4.44) | 14.80 ± 0.99 | 6 (13.33) |

| Mild | 412 | 407 (98.79) | 2 (0.46) | 1 (0.24) | 1 (0.24) | 0(0.00) | 1 (0.24) | 0(0.00) | 2 (0.48) | 14.97 ± 0.35 | 15 (3.64) | |

| Scooter-related head injury | Severe | 11 | 10 (90.91) | 1 (9.09) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 14.91 ± 0.30 | 0 (0.00) |

| Mild | 70 | 67 (95.71) | 2 (2.86) | 0(0.00) | 1 (1.43) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 14.93 ± 0.39 | 0 (0.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Foglar, V.; Süvegh, D.; Al-Smadi, M.W.; Veres, D.; Nemes, C.; Viola, Á. Electric-Scooter- and Bicycle-Related Trauma in a Hungarian Level-1 Trauma Center—A Retrospective 1-Year Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248782

Foglar V, Süvegh D, Al-Smadi MW, Veres D, Nemes C, Viola Á. Electric-Scooter- and Bicycle-Related Trauma in a Hungarian Level-1 Trauma Center—A Retrospective 1-Year Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248782

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoglar, Viktor, Dávid Süvegh, Mohammad Walid Al-Smadi, Daniel Veres, Csenge Nemes, and Árpád Viola. 2025. "Electric-Scooter- and Bicycle-Related Trauma in a Hungarian Level-1 Trauma Center—A Retrospective 1-Year Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248782

APA StyleFoglar, V., Süvegh, D., Al-Smadi, M. W., Veres, D., Nemes, C., & Viola, Á. (2025). Electric-Scooter- and Bicycle-Related Trauma in a Hungarian Level-1 Trauma Center—A Retrospective 1-Year Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248782