Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Immunocompetent Patients with Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study Shows No Survival Benefit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

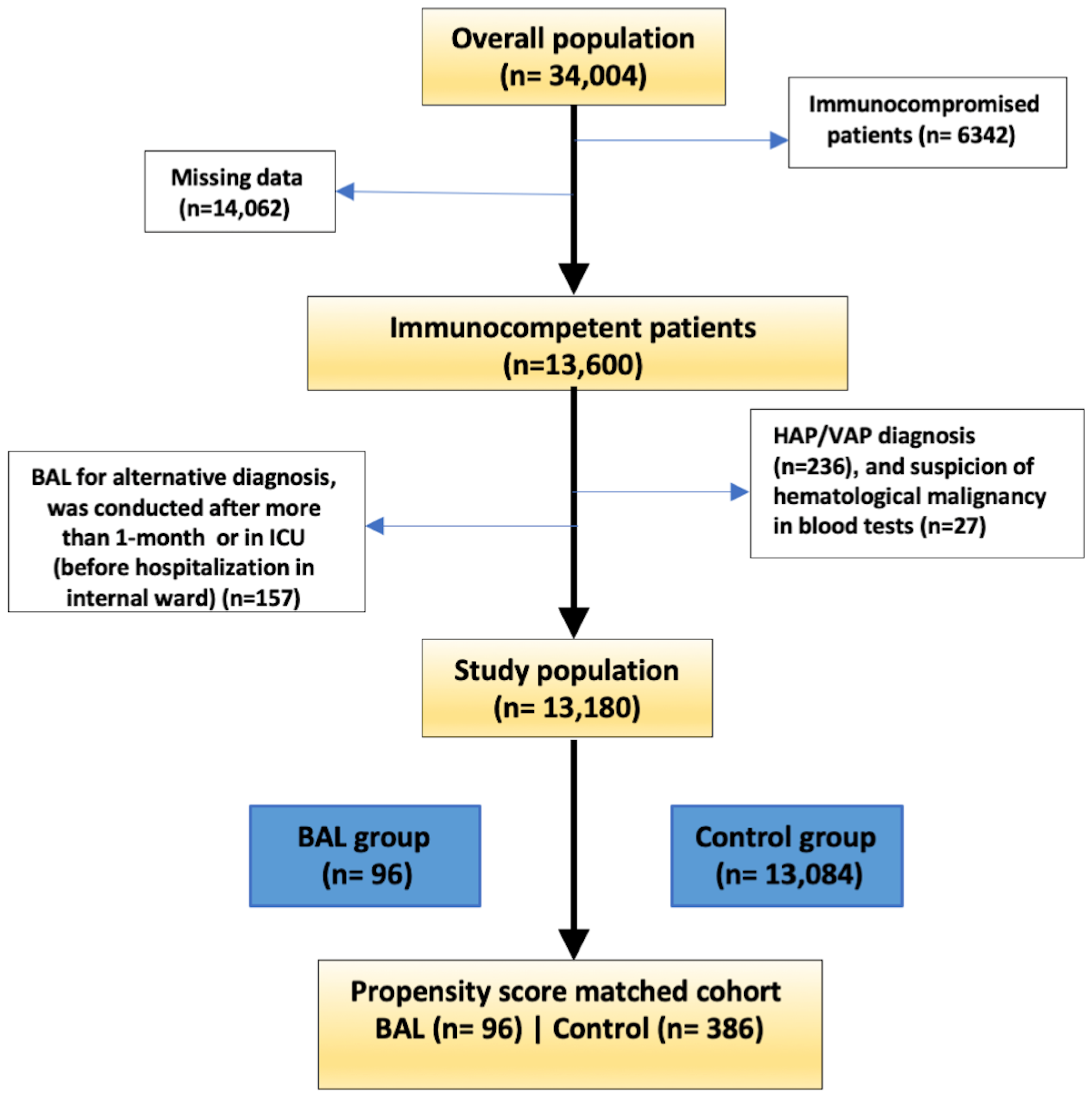

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

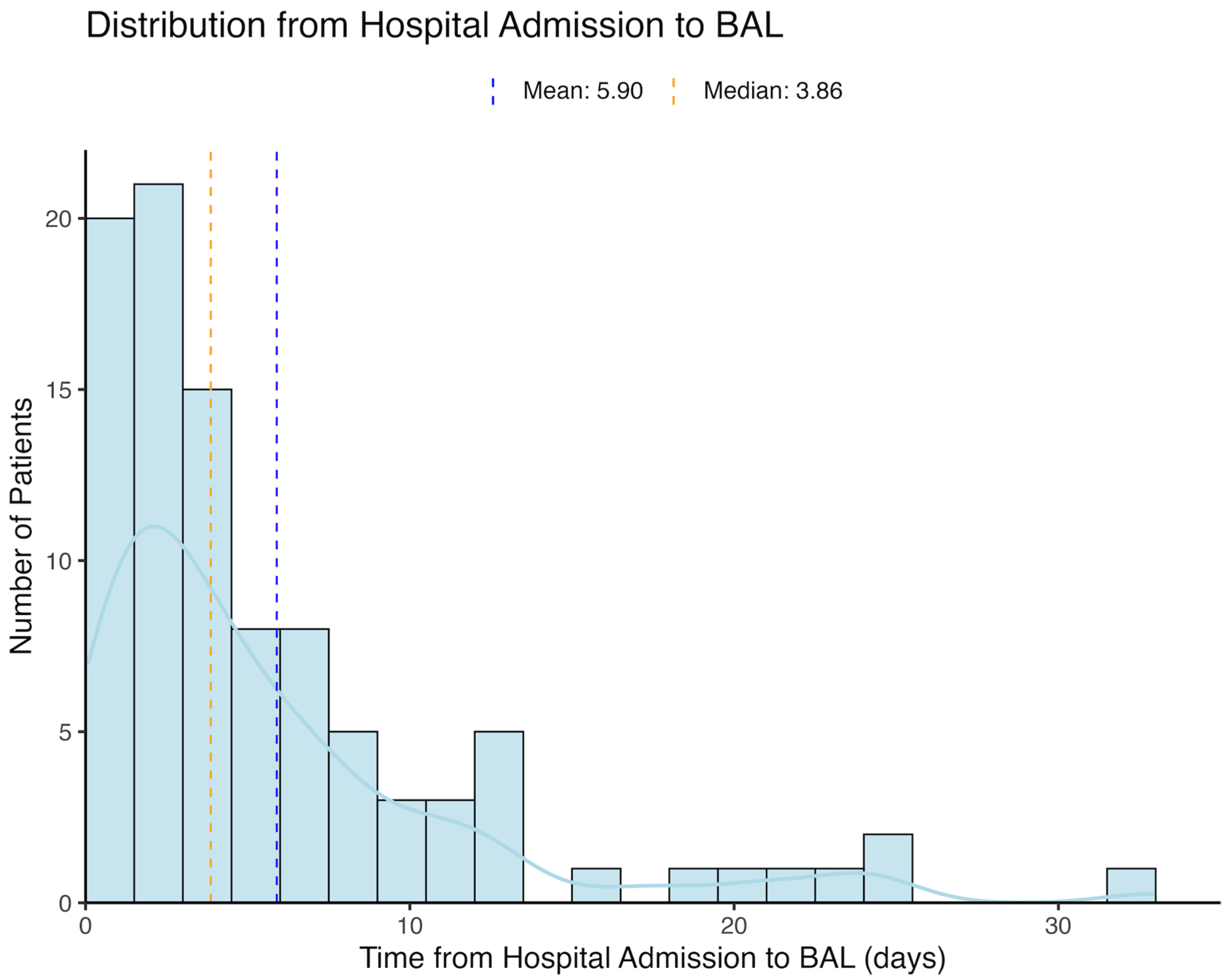

3.1. Study Population

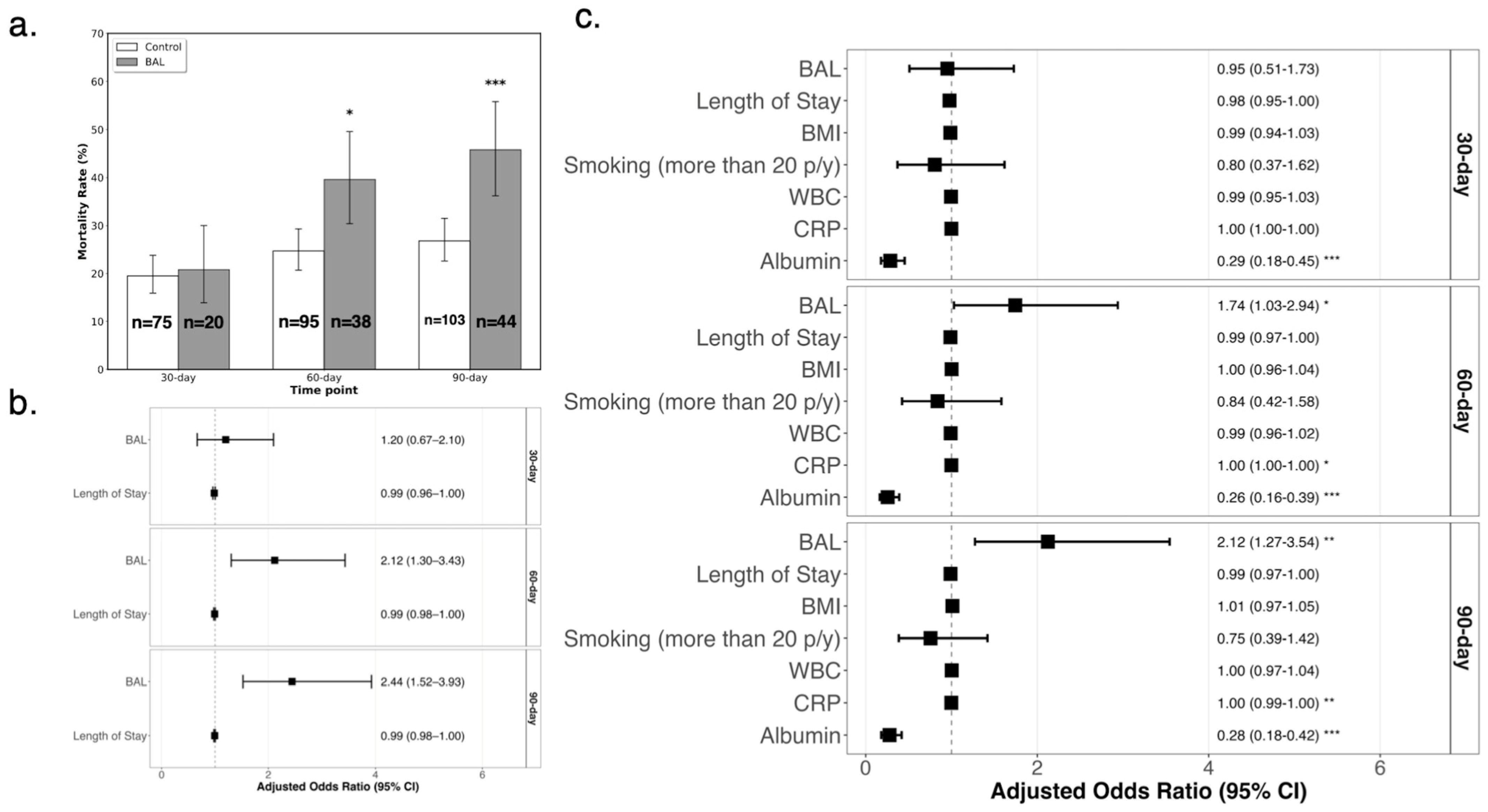

3.2. Propensity Score Matching and Mortality Analysis

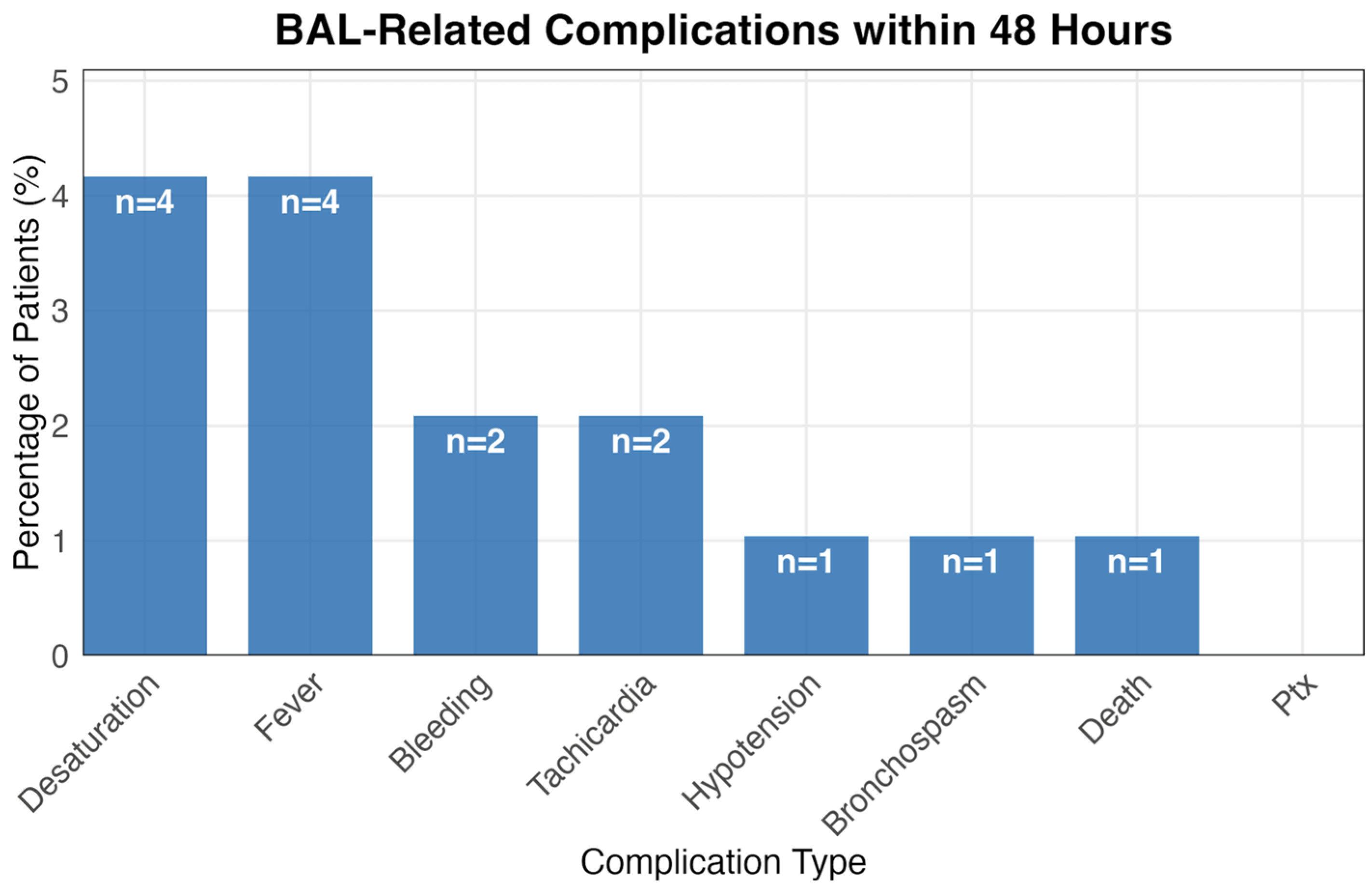

3.3. BAL-Related Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar Lavage |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CURB-65 | Confusion, Urea, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, Age ≥65 |

| HAP | Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IDSA | Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PSI | Pneumonia Severity Index |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

| VAP | Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. |

References

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Cristiana, A.; Kalankesh, L.R.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Naghavi, M.; Murray, C.J.L.; Cederroth, C.R.; Samy, A.; Silva, J.P.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.A.; Wiemken, T.L.; Peyrani, P.; Arnold, F.W.; Kelley, R.; Mattingly, W.A.; Nakamatsu, R.; Pena, S.; Guinn, B.E.; Furmanek, S.P. Adults Hospitalized With Pneumonia in the United States: Incidence, Epidemiology, and Mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.L.; Kochanek, K.D.; Xu, J.; Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief 2021, 427, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, A.; Cilloniz, C.; Niederman, M.S.; Menéndez, R.; Chalmers, J.D.; Wunderink, R.G.; van der Poll, T. Pneumonia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File, T.M.; Ramirez, J.A. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.R.; Lerner, A.; Baram, M.; Awsare, B.K. Utility of flexible bronchoscopy in the evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates in the hematopoietic stem cell transplant population—A single center fourteen year experience. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2013, 49, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, V.R.; Andersson, B.S.; Lei, X.; Champlin, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Utility of early versus late fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the evaluation of new pulmonary infiltrates following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010, 45, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rañó, A.; Agustí, C.; Benito, N.; Rovira, M.; Angrill, J.; Pumarola, T.; Torres, A. Prognostic Factors of Non-HIV Immunocompromised Patients With Pulmonary Infiltrates. Chest 2002, 122, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rano, A. Pulmonary infiltrates in non-HIV immunocompromised patients: A diagnostic approach using non-invasive and bronchoscopic procedures. Thorax 2001, 56, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qadi, M.O.; Cartin-Ceba, R.; Kashyap, R.; Kaur, S.; Peters, S.G. The Diagnostic Yield, Safety, and Impact of Flexible Bronchoscopy in Non-HIV Immunocompromised Critically Ill Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Lung 2018, 196, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownback, K.; Simpson, S. Association of bronchoalveolar lavage yield with chest computed tomography findings and symptoms in immunocompromised patients. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2013, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, R.; Anantham, D. Role of bronchoalveolar lavage in the management of immunocompromised patients with pulmonary infiltrates. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, M.M. A Diagnostic Approach to Fungal Pneumonia. Chest 2024, 165, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, I.; Hardak, E.; Zuckerman, T.; Geffen, Y.; Hoffman, R.; Yigla, M.; Avivi, I. Does molecular analysis increase the efficacy of bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis and management of respiratory infections in hemato-oncological patients? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 50, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, G.; Peter, J.; Meldau, R.; Khalfey, H.; Gina, P.; Matinyena, B.; Lenders, L.; Calligaro, G.; Allwood, B.; Symons, G.; et al. Accuracy and impact of Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of smear-negative or sputum-scarce tuberculosis using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Thorax 2013, 68, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, L.G.; Levin, M.J.; Ljungman, P.; Davies, E.G.; Avery, R.; Tomblyn, M.; Bousvaros, A.; Dhanireddy, S.; Sung, L.; Keyserling, H.; et al. Executive Summary: 2013 IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline for Vaccination of the Immunocompromised Host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.J.; Auble, T.E.; Yealy, D.M.; Hanusa, B.H.; Weissfeld, L.A.; Singer, D.E.; Coley, C.M.; Marrie, T.J.; Kapoor, W.N. A Prediction Rule to Identify Low-Risk Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.S. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: An international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003, 58, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterer, G.W.; Kessler, L.A.; Wunderink, R.G. Medium-Term Survival after Hospitalization with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 169, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, A.H.W.; Oosterheert, J.J.; Cucciolillo, M.C.; El Moussaoui, R.; Groenwold, R.H.H.; Prins, J.M.; Hoepelman, A.I.M. Cause-specific long-term mortality rates in patients recovered from community-acquired pneumonia as compared with the general Dutch population. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordon, J.; Wiemken, T.; Peyrani, P.; Paz, M.L.; Gnoni, M.; Cabral, P.; del Carmen Venero, M.; Ramirez, J.; CAPO Study Group. Decrease in Long-term Survival for Hospitalized Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Chest 2010, 138, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Self, W.H.; Wunderink, R.G.; Fakhran, S.; Balk, R.; Bramley, A.M.; Reed, C.; Grijalva, C.G.; Anderson, E.J.; Courtney, D.M.; et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Z.J.; Ashman, J.J.; Schwartzman, A.; DeFrances, C.J. National Hospital Care Survey Demonstration Projects: Examination of Inpatient Hospitalization and Risk of Mortality Among Patients Diagnosed With Pneumonia. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2022, 167, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Song, Y.-L. Advances in severe community-acquired pneumonia. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 1891–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viasus, D.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Simonetti, A.; Manresa, F.; Dorca, J.; Gudiol, F.; Carratalà, J. Prognostic value of serum albumin levels in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. 2013, 66, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwasser, P.; Feldman, J. Association of serum albumin and mortality risk. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.S.; Murray, P.; Robin, J.; Wilkinson, P.; Fluck, D.; Fry, C.H. Evaluation of the association of length of stay in hospital and outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2022, 34, mzab160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, D.; Fine, M.J.; Coley, C.M.; Marrie, T.J.; Lave, J.R.; Obrosky, D.; Kapoor, W.N.; E Singer, D. Variation in length of hospital stay in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: Are shorter stays associated with worse medical outcomes? Am. J. Med. 1999, 107, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, R.; Ferrando, D.; Vallés, J.M.; Martínez, E.; Perpiñá, M. Initial risk class and length of hospital stay in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 18, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, R.; Cremades, M.J.; Martínez-Moragón, E.; Soler, J.J.; Reyes, S.; Perpiñá, M. Duration of length of stay in pneumonia: Influence of clinical factors and hospital type. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 22, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Madaan, R.; Pokharel, S.; Bhattarai, B.; Ray, A.; Ghosh, M. Effect of Chronic Illnesses on Length of Stay and Mortality of Community Acquired Pneumonia in a Community Hospital. Am. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil, A.C.; Metersky, M.L.; Klompas, M.; Muscedere, J.; Sweeney, D.A.; Palmer, L.B.; Napolitano, L.M.; P O, N.; Bartlett, J.G.; Carratalà, J.; et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e61–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S.M.; Tran, A.; Cheng, W.; Klompas, M.; Kyeremanteng, K.; Mehta, S.; English, S.W.; Muscedere, J.; Cook, D.J.; Torres, A.; et al. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill adult patients—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellyer, T.P.; McAuley, D.F.; Walsh, T.S.; Anderson, N.; Morris, A.C.; Singh, S.; Dark, P.; I Roy, A.; Perkins, G.D.; McMullan, R.; et al. Biomarker-guided antibiotic stewardship in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAPrapid2): A randomised controlled trial and process evaluation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinsilver, S.H.; Fein, A.M.; Niederman, M.S.; Schultz, D.E.; Faegenburg, D.H. Utility of Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy in Nonresolving Pneumonia. Chest 1990, 98, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, F.; Walti, L.N.; Orchanian-Cheff, A.; Husain, S. Risk factors for COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.Y.; Lee, H.M.; Burke, A.; Bassi, G.L.; Torres, A.; Fraser, J.F.; Fanning, J.P. Prevalence, Risk Factors, Clinical Features, and Outcome of Influenza-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Critically Ill Patients. Chest 2024, 165, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feys, S.; Carvalho, A.; Clancy, C.J.; Gangneux, J.-P.; Hoenigl, M.; Lagrou, K.; A Rijnders, B.J.; Seldeslachts, L.; Vanderbeke, L.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; et al. Influenza-associated and COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.J.; Casal, R.F.; Lazarus, D.R.; Ost, D.E.; Eapen, G.A. Flexible Bronchoscopy. Clin. Chest Med. 2018, 39, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rand, I.A.; Blaikley, J.; Booton, R.; Chaudhuri, N.; Gupta, V.; Khalid, S.; Mandal, S.; Martin, J.; Mills, J.; Navani, N.; et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults: Accredited by NICE. Thorax 2013, 68 (Suppl. S1), i1–i44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strumpf, I.J.; Feld, M.K.; Cornelius, M.J.; Keogh, B.A.; Crystal, R.G. Safety of Fiberoptic Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Evaluation of Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest 1981, 80, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Control (n = 13,084) | BAL (n = 96) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age—yr | 81.0 (70.1–88.2) | 69.9 (61.1–77.1) | <0.001 |

| Male sex—no. (%) | 6865 (52.5) | 62 (64.6) | 0.023 |

| Nursing home resident—no. (%) | 790 (6.0) | 5 (5.2) | 0.900 |

| Habits | |||

| Smoking > 20 pack-years—no. (%) | 1123 (8.6) | 21 (21.9) | <0.001 |

| Body-mass index ‡ | 25.7 (24.4–27.2) | 25.7 (23.1–25.7) | 0.006 |

| Vital Signs | |||

| Respiratory rate—breaths/min | 20.0 (18.0–24.0) | 20.0 (18.0–21.2) | 0.662 |

| Hypotension §—no. (%) | 5866 (44.8) | 45 (46.9) | 0.766 |

| Temperature abnormality ¶—no. (%) | 3638 (27.8) | 19 (19.8) | 0.103 |

| Heart rate—beats/min | 92.0 (78.0–107.0) | 95.5 (81.8–110.0) | 0.203 |

| Altered mental status—no. (%) | 670 (5.1) | 10 (10.4) | 0.035 |

| Mechanical ventilation—no. (%) | 715 (5.5) | 14 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory Values | |||

| White-cell count—×109/L | 11.5 (8.5–15.5) | 12.2 (9.1–15.6) | 0.394 |

| Neutrophils—×109/L | 9.3 (6.5–13.0) | 9.9 (7.1–13.4) | 0.365 |

| Lymphocytes—×109/L | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.887 |

| Hemoglobin—g/dL | 12.0 (11.4–12.7) | 12.0 (12.0–12.1) | 0.740 |

| Hematocrit—% | 38.0 (34.5–42.0) | 38.0 (38.0–43.9) | 0.042 |

| Platelet count—×109/L | 231.0 (176.0–301.0) | 255.0 (199.5–399.2) | 0.002 |

| Sodium—mmol/L | 137.0 (134.0–140.2) | 136.0 (133.5–138.6) | 0.007 |

| Glucose—mg/dL | 141.0 (116.0–188.0) | 131.0 (108.8–176.2) | 0.060 |

| Urea—mg/dL | 52.0 (36.0–79.0) | 38.5 (30.0–67.5) | <0.001 |

| Albumin—g/dL | 3.4 (3.1–3.8) | 3.2 (2.8–3.4) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine—mg/dL | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.005 |

| Total bilirubin—mg/dL | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.127 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase—U/L | 279.0 (222.0–365.0) | 279.0 (219.0–437.0) | 0.651 |

| C-reactive protein—mg/L | 91.1 (33.5–163.6) | 111.3 (63.1–218.2) | 0.003 |

| pH | 7.4 (7.3–7.4) | 7.4 (7.3–7.4) | 0.056 |

| Lactate—mmol/L | 18.0 (14.0–25.0) | 18.0 (15.0–26.0) | 0.208 |

| Chest Radiographic Finding | |||

| Pleural effusion—no. (%) | 346 (2.6) | 3 (3.1) | 0.743 |

| Coexisting Conditions—no. (%) | |||

| COPD | 1483 (11.3) | 11 (11.5) | 1.000 |

| Bronchiectasis | 138 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 0.272 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 60 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2429 (18.6) | 10 (10.4) | 0.055 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 627 (4.8) | 5 (5.2) | 1.000 |

| Previous stroke or TIA | 2378 (18.2) | 10 (10.4) | 0.067 |

| Liver disease | 191 (1.5) | 2 (2.1) | 0.653 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1898 (14.5) | 8 (8.3) | 0.117 |

| Diabetes | 3756 (28.7) | 20 (20.8) | 0.113 |

| Hypertension | 6673 (51.0) | 27 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1599 (12.2) | 4 (4.2) | 0.012 |

| Severity and Length of Stay | |||

| CURB-65 score ‖ | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.176 |

| Pneumonia severity index | 106.0 (84.0–131.0) | 100.5 (76.0–123.0) | 0.045 |

| Length of stay—days | 2.9 (1.5–6.0) | 9.9 (4.4–14.9) | <0.001 |

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | BAL | Control | p-Value | BAL | Control | p-Value |

| n | 96 | 13,084 | 96 | 384 | ||

| Age (years) | 69.92 [61.11, 77.13] | 80.97 [70.13, 88.15] | <0.001 | 69.92 [61.11, 77.13] | 70.91 [54.02, 81.73] | 0.563 |

| Pneumonia Severity Index | 100.50 [76.00, 123.00] | 106.00 [84.00, 131.00] | 0.045 | 100.50 [76.00, 123.00] | 99.00 [76.00, 128.00] | 0.803 |

| CURB-65 | 1.00 [1.00, 2.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 2.00] | 0.176 | 1.00 [1.00, 2.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 2.00] | 0.752 |

| Length of Stay (days) | 9.92 [4.36, 14.91] | 2.88 [1.49, 5.96] | <0.001 | 9.92 [4.36, 14.91] | 3.40 [1.62, 7.37] | <0.001 |

| Gender | 62 (64.6) | 6865 (52.5) | 0.018 | 62 (64.6) | 263 (68.5) | 0.464 |

| Pulmonary Diseases | 13 (13.5) | 1619 (12.4) | 0.729 | 13 (13.5) | 61 (15.9) | 0.569 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 22 (22.9) | 4360 (33.3) | 0.031 | 22 (22.9) | 86 (22.4) | 0.913 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 8 (8.3) | 1898 (14.5) | 0.087 | 8 (8.3) | 28 (7.3) | 0.729 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 4 (4.2) | 1599 (12.2) | 0.016 | 4 (4.2) | 12 (3.1) | 0.611 |

| Diabetes | 20 (20.8) | 3756 (28.7) | 0.089 | 20 (20.8) | 78 (20.3) | 0.910 |

| Hypertension | 27 (28.1) | 6673 (51.0) | <0.001 | 27 (28.1) | 100 (26.0) | 0.679 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pomerantz, A.; Yaacov, A.; Goldman, A.; Deri, O.; Zlotnik, A.; Lahav, E.; Israel Sailes, P.; Huszti, E.; Levy, L. Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Immunocompetent Patients with Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study Shows No Survival Benefit. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8785. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248785

Pomerantz A, Yaacov A, Goldman A, Deri O, Zlotnik A, Lahav E, Israel Sailes P, Huszti E, Levy L. Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Immunocompetent Patients with Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study Shows No Survival Benefit. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8785. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248785

Chicago/Turabian StylePomerantz, Alon, Adar Yaacov, Adam Goldman, Ofir Deri, Asaf Zlotnik, Eden Lahav, Paz Israel Sailes, Ella Huszti, and Liran Levy. 2025. "Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Immunocompetent Patients with Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study Shows No Survival Benefit" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8785. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248785

APA StylePomerantz, A., Yaacov, A., Goldman, A., Deri, O., Zlotnik, A., Lahav, E., Israel Sailes, P., Huszti, E., & Levy, L. (2025). Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Immunocompetent Patients with Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study Shows No Survival Benefit. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8785. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248785