Leadless Pacemakers in Complex Congenital Heart Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

Epidemiology

2. Leadless Pacing

2.1. History of Leadless of Pacemakers

2.2. Rationale for Leadless Pacemakers

- Avoidance of atrio-ventricular valve interference;

- No long-term vascular dwell;

- No baffle obstruction;

- Potentially psychologically (cosmetically) better due to elimination of generators [25].

2.3. Leadless Pacemakers

2.3.1. Current Options

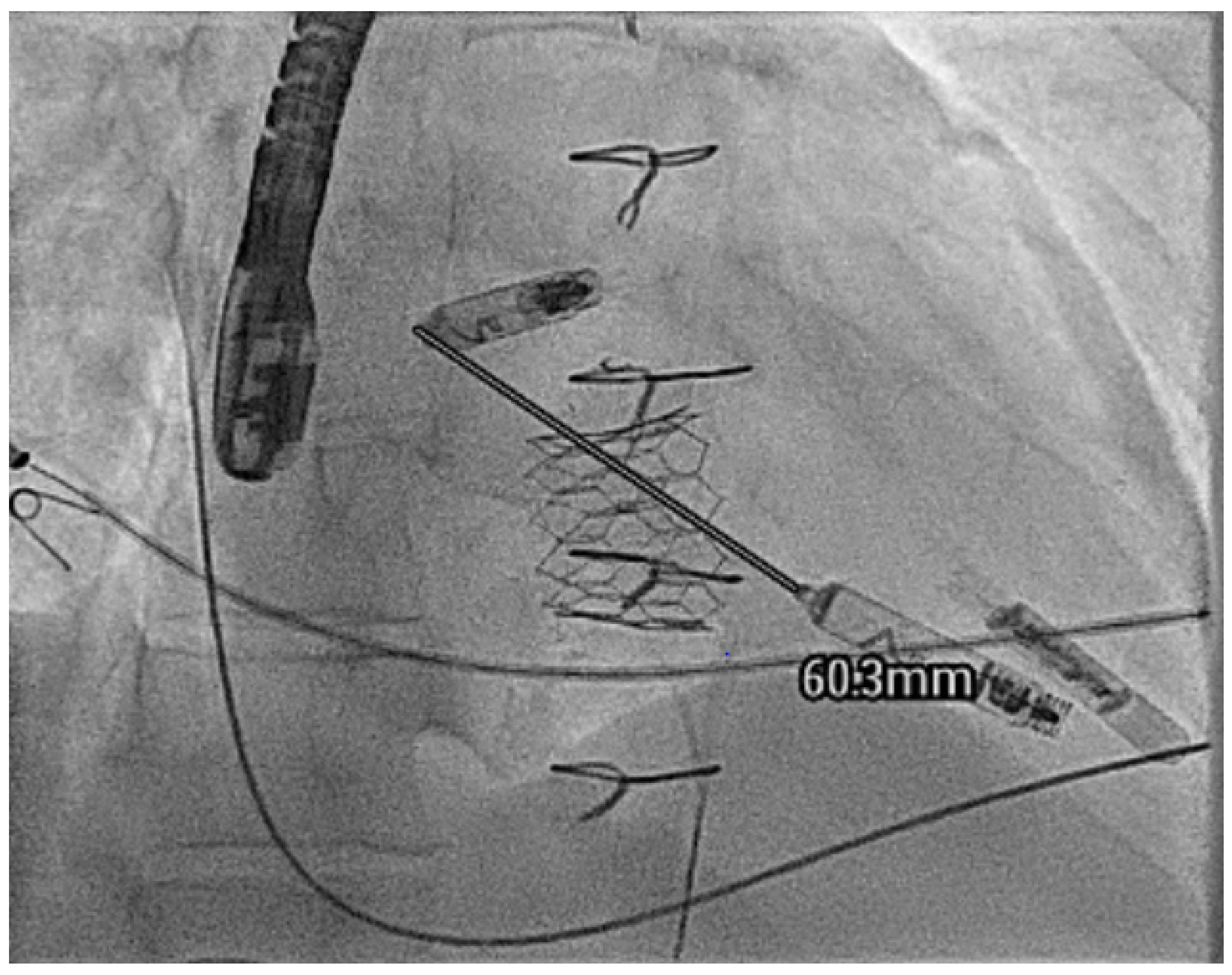

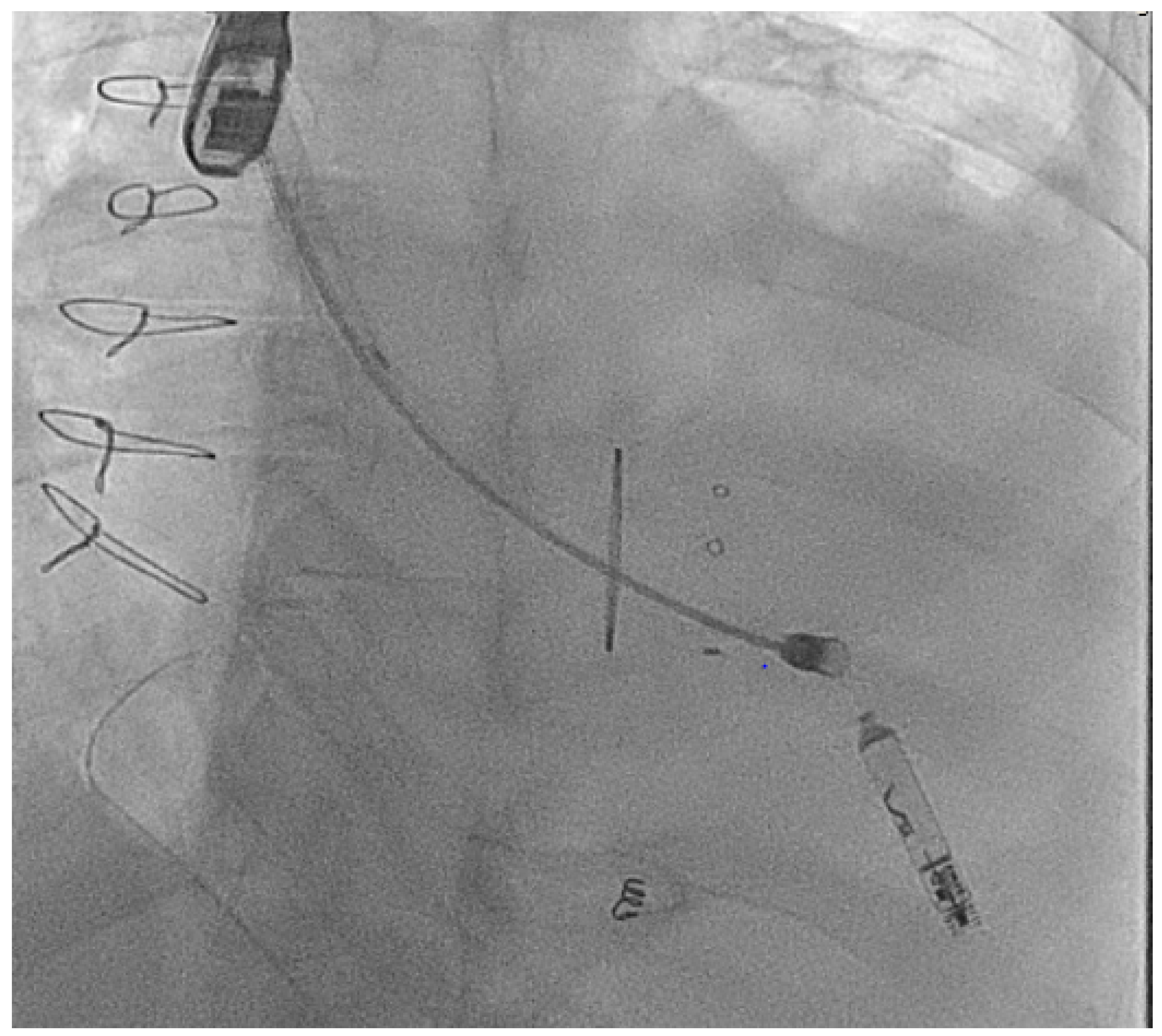

2.3.2. Access Considerations

2.3.3. Anticoagulation

2.3.4. Vessel Closure

2.3.5. Retrieval Considerations

- Vascular anomalies precluding easy femoral access;

- Multiple abandoned leads causing obstruction;

- Valve replacements;

- Significant calcification;

- Significant anatomical challenges such as very small or rotated sub-pulmonary ventricles such as in Ebstein’s anomaly.

2.3.6. Complications

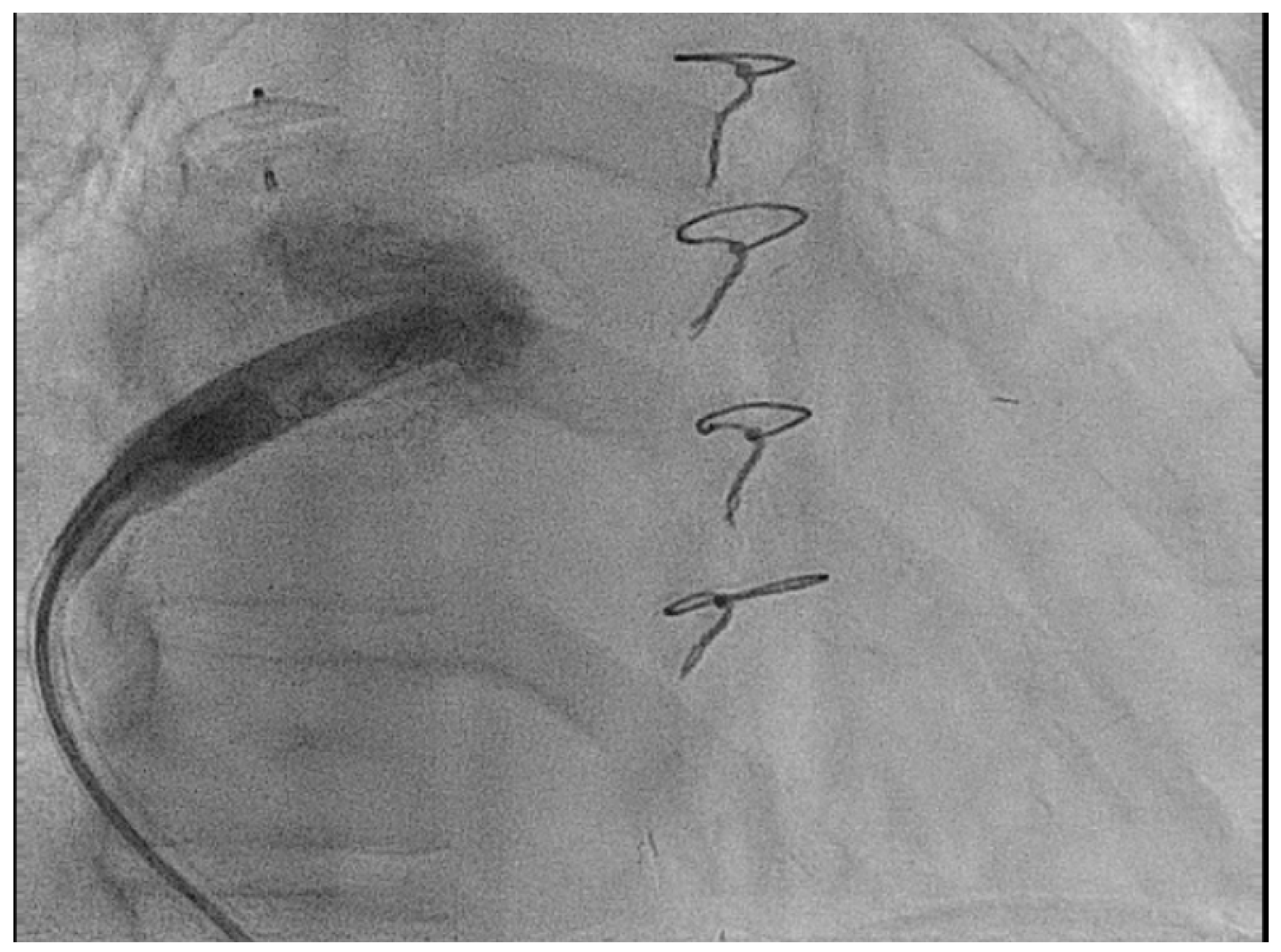

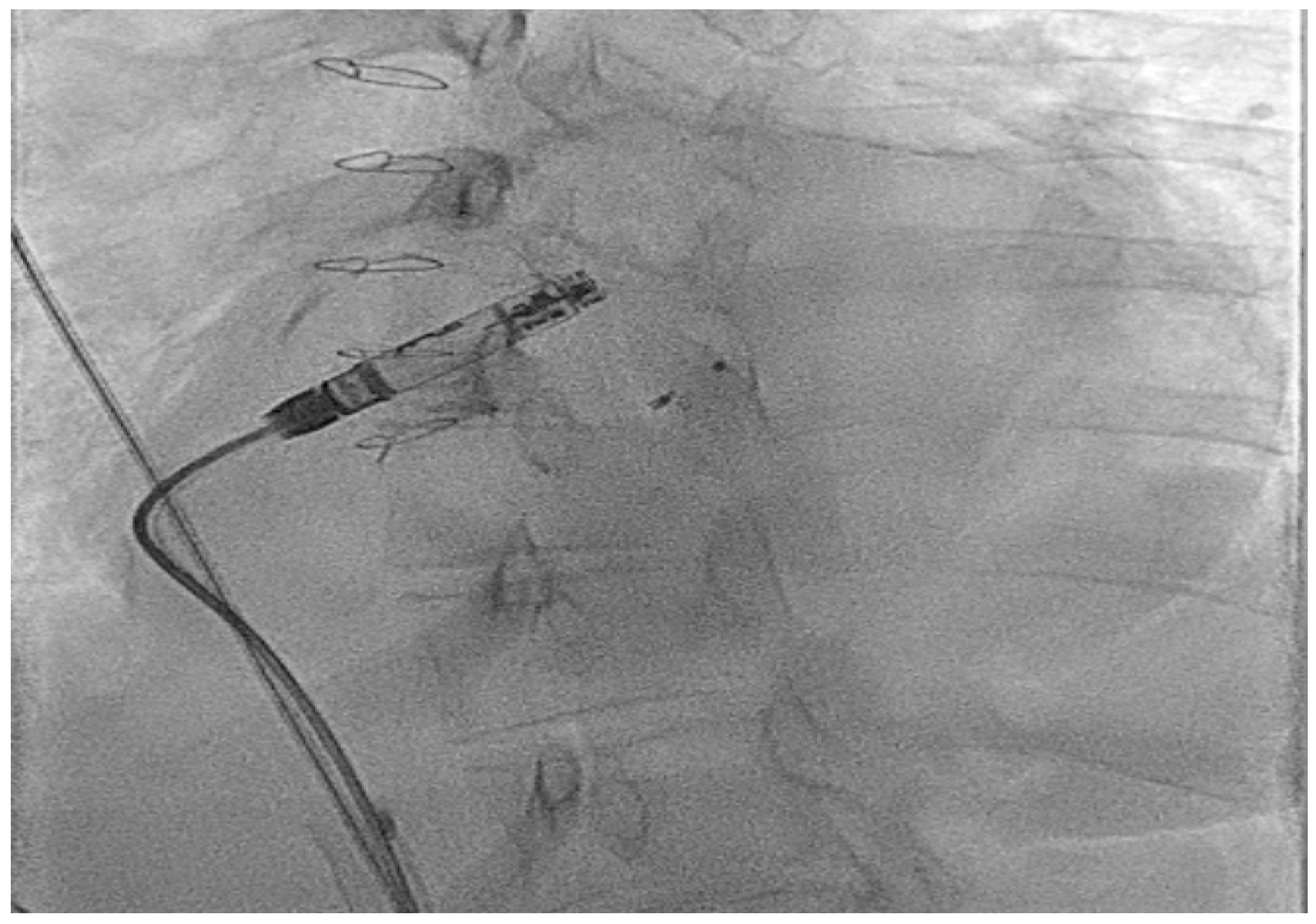

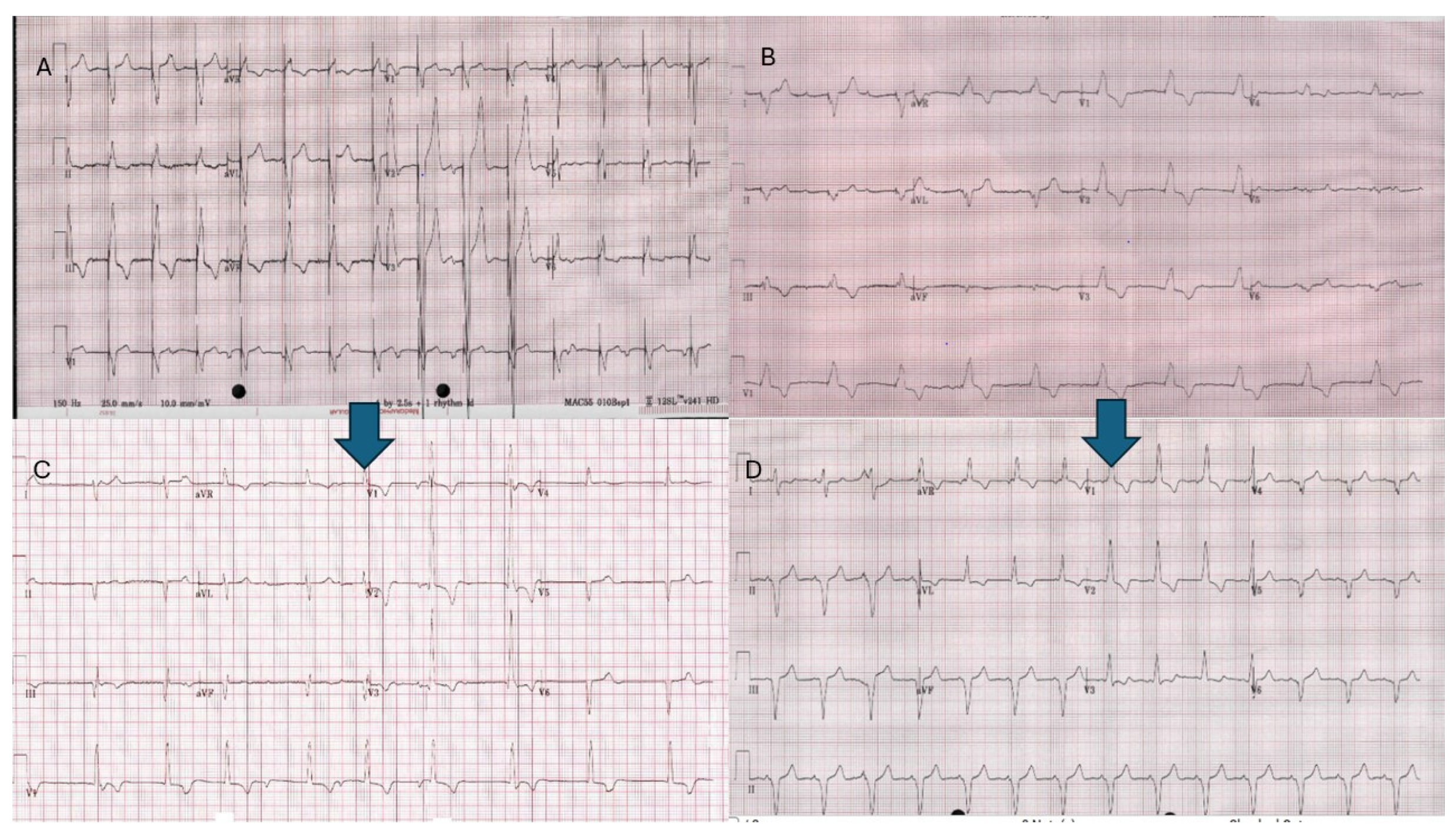

2.3.7. Atrial Leadless Pacemakers in CHD

2.3.8. Ventricular Leadless Pacemakers in CHD

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoffman, J.I.E.; Kaplan, S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, K.; Draper, E.; Kurinczuk, J.; Stoianova, S.; Tucker, D.; Wellesley, D.; Rankin, J. OP29 The prevalence of congenital heart disease in the UK: A population-based register study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68 (Suppl. S1), A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellborg, M.; Giang, K.W.; Eriksson, P.; Liden, H.; Fedchenko, M.; Ahnfelt, A.; Rosengren, A.; Mandalenakis, Z. Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Trends in Event-Free Survival Past Middle Age. Circulation 2023, 147, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholeif, Z.; Abozied, O.; Abdelhalim, A.T.; ElZalabany, S.; Moustafa, A.; Ali, A.; Egbe, A.C. Temporal change in the age at time of death in adults with congenital heart disease. Int. J. Cardiol. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2025, 20, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, J.; Moore, B.M.; Nicholson, C.; Cordina, R.; Baker, D.; Celermajer, D.S. Outcomes of permanent pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in an adult congenital heart disease population. Int. J. Cardiol. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2024, 15, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.G.; Gross, T.P.; Kaczmarek, R.G.; Hamilton, P.; Hamburger, S. The epidemiology of pacemaker implantation in the United States. Public Health Rep. 1995, 110, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji, S.; Sreeram, N. The development of pacing induced ventricular dysfunction is influenced by the underlying structural heart defect in children with congenital heart disease. Indian Heart J. 2017, 69, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midha, D.; Chen, Z.; Jones, D.G.; Williams, H.J.; Lascelles, K.; Jarman, J.; Clague, J.; Till, J.; Dimopoulos, K.; Babu-Narayan, S.V.; et al. Pacing in congenital heart disease—A four-decade experience in a single tertiary centre. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 241, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.C.; William Gaynor, J.; Fuller, S.M.; Karen, A.S.; Shah, M.J. Long-term atrial and ventricular epicardial pacemaker lead survival after cardiac operations in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiten, M.S.; van der Heijden, A.C.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Schalij, M.J.; van Erven, L. Epicardial leads in adult cardiac resynchronization therapy recipients: A study on lead performance, durability, and safety. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeriouh, S.; Koutbi, L.; Mancini, J.; Maille, B.; Hourdain, J.; Franceschi, F.; Deharo, J.C. Permanent epicardial pacing: A first line strategy in children. Europace 2024, 26 (Suppl. S1), euae102-521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, H.C.; Shannon, K.M.; Biniwale, R.; Moore, J.P. Cardiac implantable device outcomes and lead survival in adult congenital heart disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 324, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug, D.; Vaksmann, G.; Jarwé, M.; Wallet, F.; Francart, C.; Kacet, S.; Rey, C. Pacemaker Lead Infection in Young Patients. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2003, 26 Pt 1, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehill, R.D.; Chandler, S.F.; DeWitt, E.; Abrams, D.J.; Walsh, E.P.; Kelleman, M.; Mah, D.Y. Lead age as a predictor for failure in pediatrics and congenital heart disease. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2021, 44, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Ramwell, C.B.; Lewis, A.R.; Ogueri, V.N.; Choi, N.H.; Algebaly, H.F.; Barber, J.R.; Berul, C.I.; Sherwin, E.D.; Moak, J.P. Lead Longevity in Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease Patients: The Impact of Patient Somatic Growth. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2025, 11, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Chami, M.F.; Garweg, C.; Clementy, N.; Al-Samadi, F.; Iacopino, S.; Martinez-Sande, J.L.; Roberts, P.R.; Tondo, C.; Johansen, J.B.; Vinolas-Prat, X.; et al. Leadless pacemakers at 5-year follow-up: The Micra transcatheter pacing system post-approval registry. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, A.; Breitenstein, A.; Piccini, J.P. Long-term management of leadless pacemakers. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2025, 27 (Suppl. S2), ii26–ii38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.R.; Galloti, R.; Moore, J.P. Initial experience with transcatheter pacemaker implantation for adults with congenital heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2019, 30, 1362–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassareo, P.P.; Walsh, K.P. Micra pacemaker in adult congenital heart disease patients: A case series. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2022, 33, 2335–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.J.; Borquez, A.A.; Cortez, D.; McCanta, A.C.; De Filippo, P.; Whitehill, R.D.; Imundo, J.R.; Moore, J.P.; Sherwin, E.D.; Howard, T.S.; et al. Transcatheter Leadless Pacing in Children: A PACES Collaborative Study in the Real-World Setting. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2023, 16, e011447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, E.D.; Shah, M.J. Leadless Pacemakers in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2023, 15, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Exner, D.V.; Cantillon, D.J.; Doshi, R.; Bunch, T.J.; Tomassoni, G.F.; Friedman, P.A.; Estes, N.A., 3rd; Ip, J.; Niazi, I.; et al. Percutaneous Implantation of an Entirely Intracardiac Leadless Pacemaker. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Knops, R.E.; Sperzel, J.; Miller, M.A.; Petru, J.; Simon, J.; Sediva, L.; de Groot, J.R.; Tjong, F.V.; Jacobson, P.; et al. Permanent leadless cardiac pacing: Results of the LEADLESS trial. Circulation 2014, 129, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Chami, M.F.; Bonner, M.; Holbrook, R.; Stromberg, K.; Mayotte, J.; Molan, A.; Sohail, M.R.; Epstein, L.M. Leadless pacemakers reduce risk of device-related infection: Review of the potential mechanisms. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, S.F.; Jordan, E.W.; Hashmath, Z.; Sargeant, M.M.; Catanzaro, J.; Nekkanti, R.; Shantha, G. Leadless Pacemakers: The “Leading Edge” of Quality of Life in Cardic Electrophysiology. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2025, 27, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretta, D.M.; Tomasi, L.; Tondo, C.; De Filippo, P.; Nigro, G.; Zucchelli, G.; Nicosia, A.; Coppola, G.; Bontempi, L.; Sgarito, G.; et al. Leadless Micra pacemakers: Estimating long-term longevity. A real word data analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 426, 133062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Exner, D.V.; Doshi, R.; Tomassoni, G.; Bunch, T.J.; Friedman, P.; Estes, N.A.M.; Neužil, P.; de la Concha, J.F.; Cantillon, D.J. 1-Year Outcomes of a Leadless Ventricular Pacemaker: The LEADLESS II (Phase 2) Trial. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9 Pt 2, 1187–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Felten, E.; Breitenstein, A.; Müller, A.; Wiederkehr, C.; Brix, T.; Jeger, R.; Hofer, D. First European experience with a leadless atrial pacemaker. Heart Rhythm O2 2025, 6, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjong, F.V.Y.; Brouwer, T.F.; Koop, B.; Soltis, B.; Shuros, A.; Schmidt, B.; Swackhamer, B.; Quast, A.-F.E.B.; Wilde, A.A.M.; Burke, M.C.; et al. Acute and 3-Month Performance of a Communicating Leadless Antitachycardia Pacemaker and Subcutaneous Implantable Defibrillator. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2017, 3, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, N.; Mehta, V.; Vere, F.; Howell, S.; Behar, J.M.; Shute, A.; Lee, M.; Bosco, P.; Niederer, S.A.; Rinaldi, C.A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of leadless cardiac resynchronization therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2023, 34, 2590–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBR. WiSE® Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) System. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf24/P240028D.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Reddy, V.Y.; Nair, D.G.; Doshi, S.K.; Doshi, R.N.; Chovanec, M.; Ganz, L.; Sabet, L.; Jiang, C.; Neuzil, P. First-in-human study of a leadless pacemaker system for left bundle branch area pacing. Heart Rhythm 2025, 22, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.S.; Brisben, A.J.; Reddy, V.Y.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boersma, L.V.A.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Burke, M.C.; Cantillon, D.J.; Doshi, R.; Friedman, P.A.; et al. Design and rationale of the MODULAR ATP global clinical trial: A novel intercommunicative leadless pacing system and the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm O2 2023, 4, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, J.R.; Ing, F.F. Stenting of stenotic or occluded iliofemoral veins, superior and inferior vena cavae in children with congenital heart disease: Acute results and intermediate follow up. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 73, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, D.W.; Abdelhameed, A.M.; Mohammad, S.A.; Abbas, S.N. CT of cardiac and extracardiac vascular anomalies: Embryological implications. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021, 52, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, L.V.; El-Chami, M.; Steinwender, C.; Lambiase, P.; Murgatroyd, F.; Mela, T.; Theuns, D.A.M.J.; Khelae, S.K.; Kalil, C.; Zabala, F.; et al. Practical considerations, indications, and future perspectives for leadless and extravascular cardiac implantable electronic devices: A position paper by EHRA/HRS/LAHRS/APHRS. Europace 2022, 24, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.I.; Jackson, N.; Smith, A.; Black, S.A. A Systematic Review of the Safety and Efficacy of Inferior Vena Cava Stenting. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2023, 65, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, D.; Horizoe, Y.; Tabata, H.; Uchiyama, Y.; Ohishi, M. Crossover Buddy Wire–Assisted Delivery of Steerable Guide Catheter. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltsov, I.; Sorgente, A.; de Asmundis, C.; La Meir, M. First in human surgical implantation of a leadless pacemaker on the epicardial portion of the right atrial appendage in a patient with a cardiac electronic devices mediated dermatitis. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 35, ivac050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Peck, D.; Narasimhan, S.; Von Bergen, N.H. Epicardial Implantation of a Micra™ Pacemaker in a Premature Neonate with Congenital Complete Heart Block. J. Innov. Card. Rhythm. Manag. 2024, 15, 5739–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

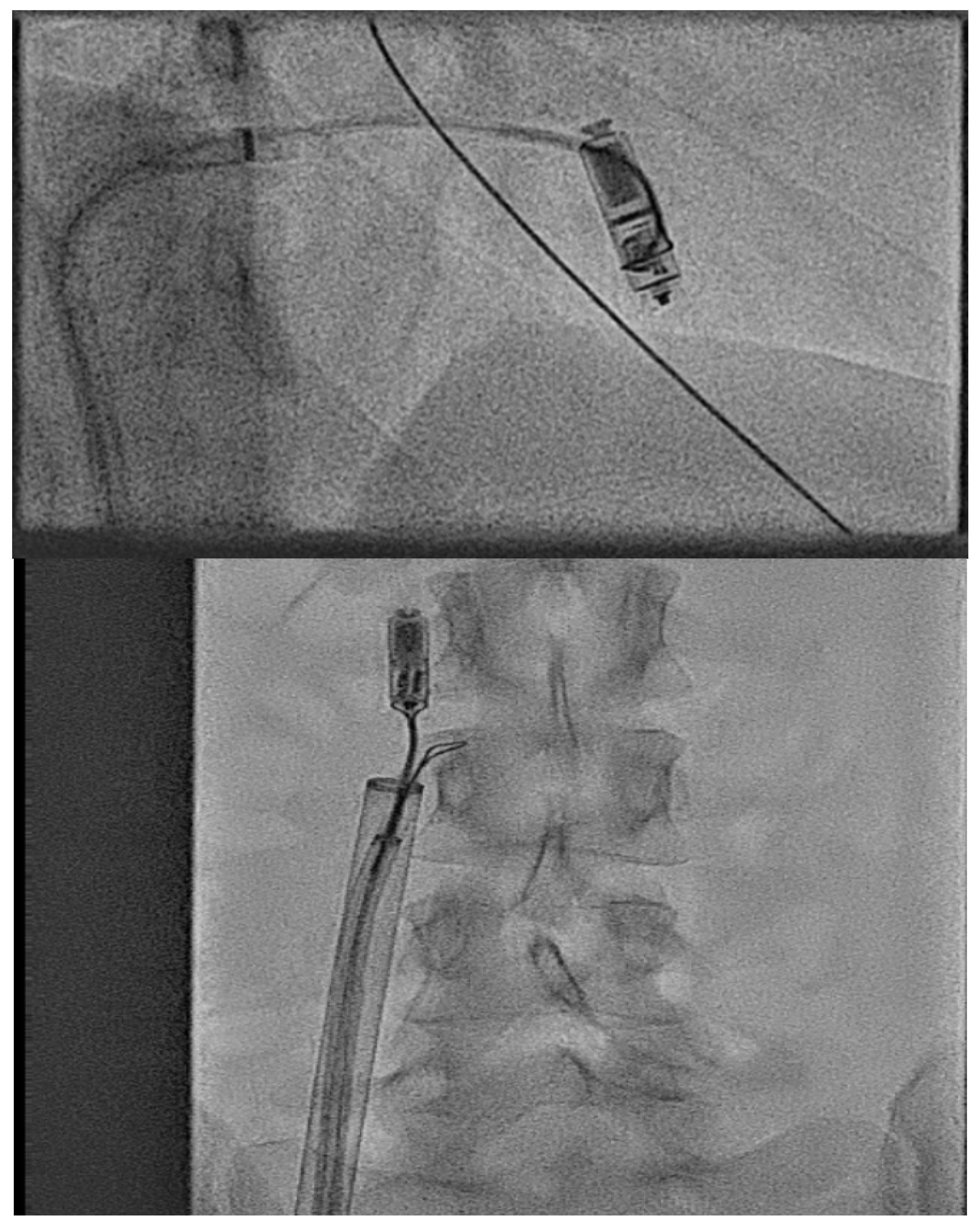

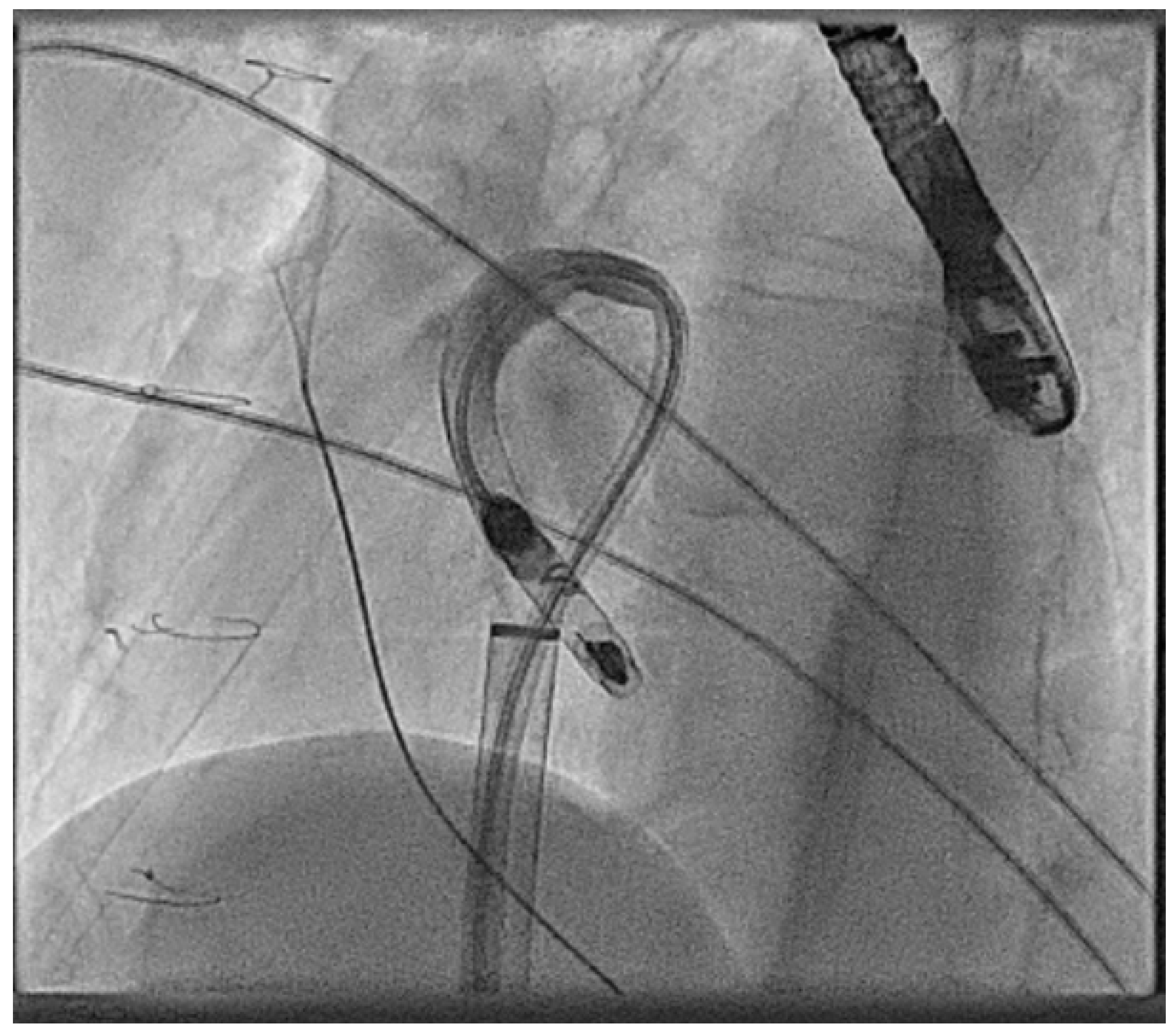

- Calvert, P.; Yeo, C.; Rao, A.; Neequaye, S.; Mayhew, D.; Ashrafi, R. Transcarotid implantation of a leadless pacemaker in a patient with Fontan circulation. Hear. Case Rep. 2023, 9, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. What is Parylene Coating and When Should you Use it? 2019. Available online: https://mechanical-engineering.com/what-is-parylene-coating-its-use/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Paraggio, L.; Bianchini, F.; Aurigemma, C.; Romagnoli, E.; Bianchini, E.; Zito, A.; Lunardi, M.; Trani, C.; Burzotta, F. Femoral Large Bore Sheath Management: How to Prevent Vascular Complications From Vessel Puncture to Sheath Removal. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, e014156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.T.; Calvert, P.; Snowdon, R.; Mahida, S.; Waktare, J.; Borbas, Z.; Ashrafi, R.; Todd, D.; Modi, S.; Luther, V.; et al. Suture-based techniques versus manual compression for femoral venous haemostasis after electrophysiology procedures. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 2119–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzil, P.; Exner, D.V.; Knops, R.E.; Cantillon, D.J.; Defaye, P.; Banker, R.; Friedman, P.; Hubbard, C.; Delgado, S.M.; Bulusu, A.; et al. Worldwide Chronic Retrieval Experience of Helix-Fixation Leadless Cardiac Pacemakers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, R.G.; Gornick, C.C.; Abdelhadi, R.H.; Tang, C.Y.; Casey, S.A.; Sengupta, J.D. Major adverse clinical events associated with implantation of a leadless intracardiac pacemaker. Heart Rhythm 2021, 18, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, Y.; Ullah, W.; Roomi, S.; Rauf, H.; Mukhtar, M.; Ahmad, A.; Ali, Z.; Abedin, M.S.; Alraies, M.C. Complications of leadless vs conventional (lead) artificial pacemakers—A retrospective review. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2020, 10, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, P.; Facchin, D.; Ziacchi, M.; Nigro, G.; Nicosia, A.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Tomasi, L.; Rossi, A.; De Filippo, P.; Sgarito, G.; et al. Rate and nature of complications with leadless transcatheter pacemakers compared with transvenous pacemakers: Results from an Italian multicentre large population analysis. Europace 2023, 25, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschel, T.J.; Gruszka, A.; Hermanns-Sachweh, B.; Elyakoubi, J.; Sachweh, J.S.; Vázquez-Jiménez, J.F.; Schnoering, H. Prevention of Postoperative Pericardial Adhesions With TachoSil. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubietah, A.; Singh, A.; Qafisheh, Q.; Razminia, P.; Baniowda, M.; Assaassa, A.; Taha, H.I.; Aljunaidi, R. Silent misplacement: Leadless pacemaker in the left ventricle discovered over a year later-How did it end up there? Could it explain the stroke? Oxf. Med. Case Rep. 2025, 2025, omaf117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

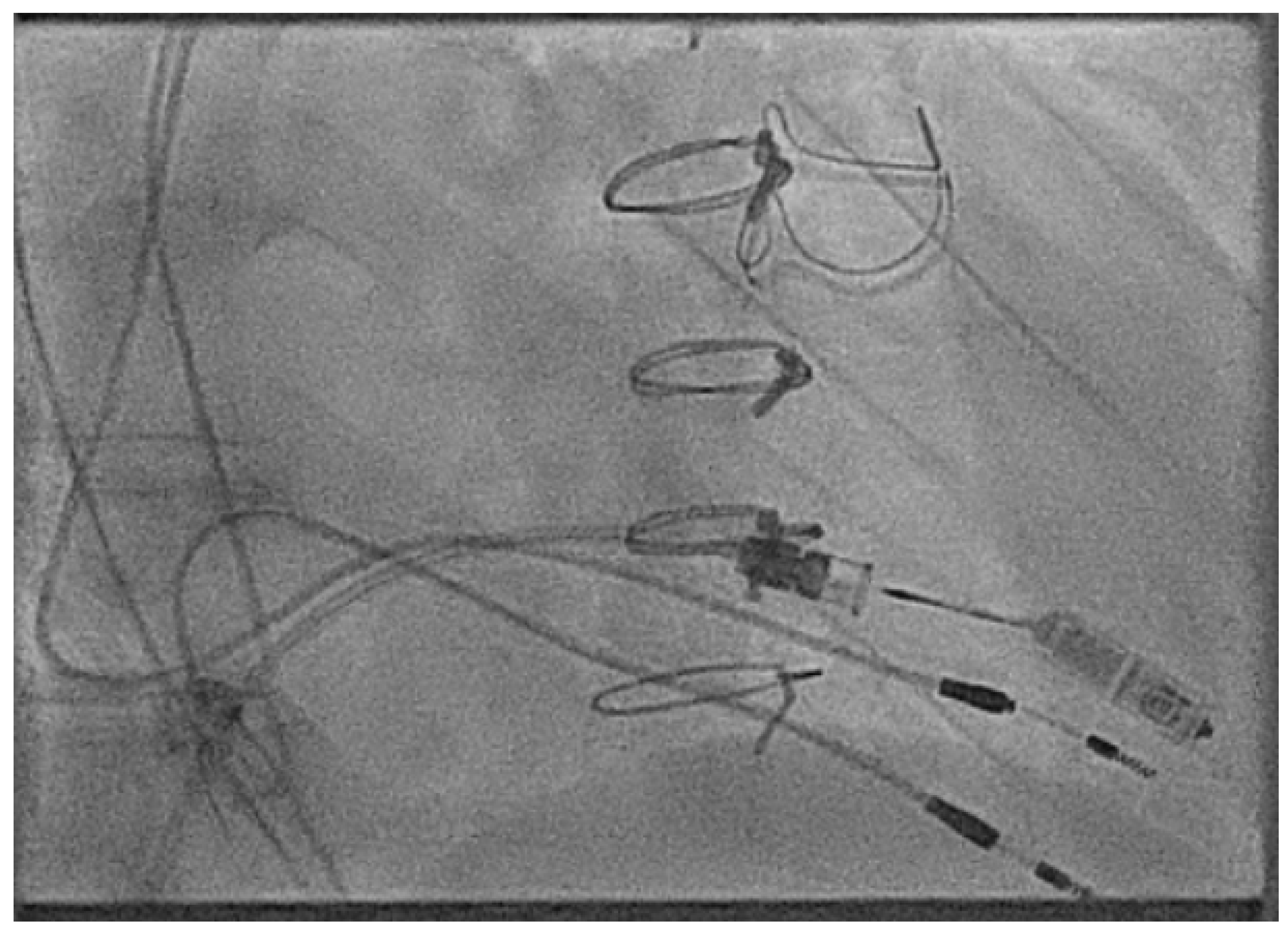

- Pinon, P.; Iserin, L.; Hachem, F.; Waldmann, V. First in man right atrial appendage implantation of a Micra leadless pacemaker. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 1232–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Murphy, N.; Walsh, K.P. Fist in man implantation of a leadless pacemaker in the left atrial appendage following Mustard repair. Europace 2021, 24, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knops, R.E.; Reddy, V.Y.; Ip, J.E.; Doshi, R.; Exner, D.V.; Defaye, P.; Canby, R.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Shoda, M.; Hindricks, G.; et al. A Dual-Chamber Leadless Pacemaker. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2360–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantillon, D.J.; Gambhir, A.; Banker, R.; Rashtian, M.; Doshi, R.; Badie, N.; Booth, D.; Yang, W.; Nee, P.; Fishler, M.; et al. Wireless Communication Between Paired Leadless Pacemakers for Dual-Chamber Synchrony. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, e010909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, B.W.; Devanagondi, R.; Aldoss, O.; Olson, M.D.; Law, I.H. Transvenous endocardial conduction system pacing in patients with a Fontan operation. Hear. Case Rep. 2025, 11, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.H.P.; Herring, N.; Ginks, M.R.; Rajappan, K.; Bashir, Y.; Betts, T.R. Endocardial left ventricular pacing across the interventricular septum for cardiac resynchronization therapy: Clinical results of a pilot study. Heart Rhythm 2018, 15, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overtchouk, P.; Alqdeimat, I.; Coisne, A.; Fattouch, K.; Modine, T. Transcarotid approach for TAVI: An optimal alternative to the transfemoral gold standard. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 6, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

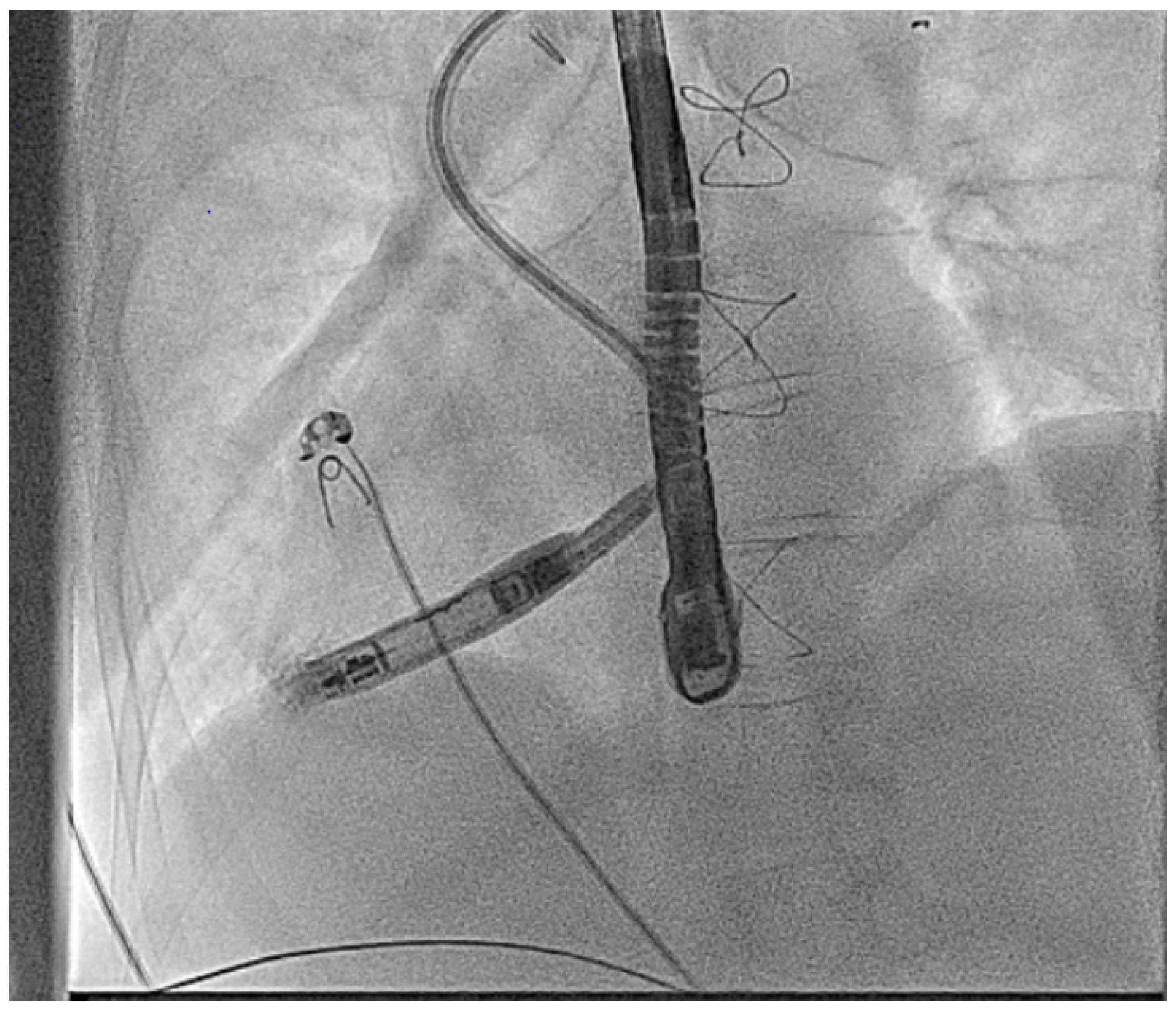

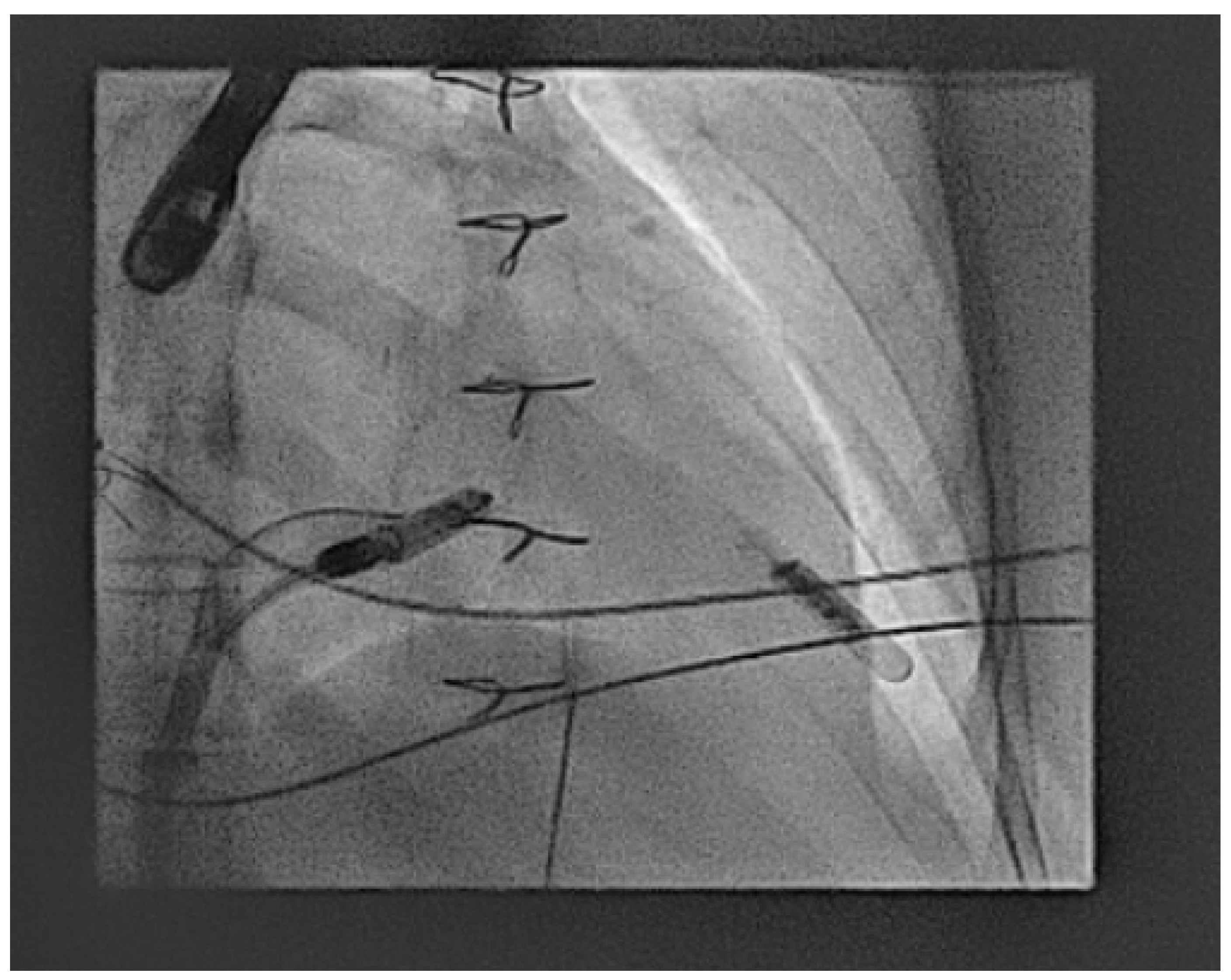

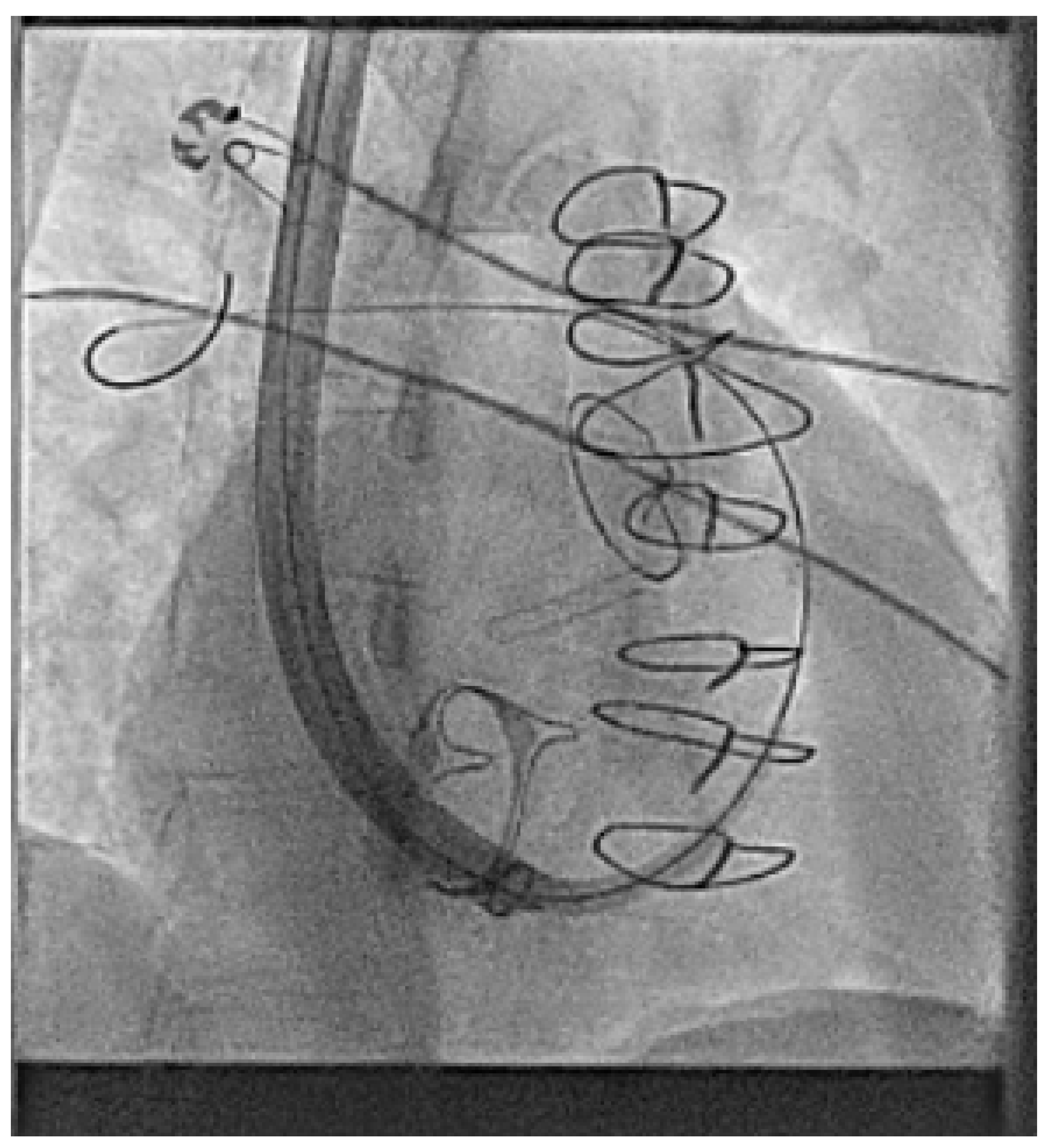

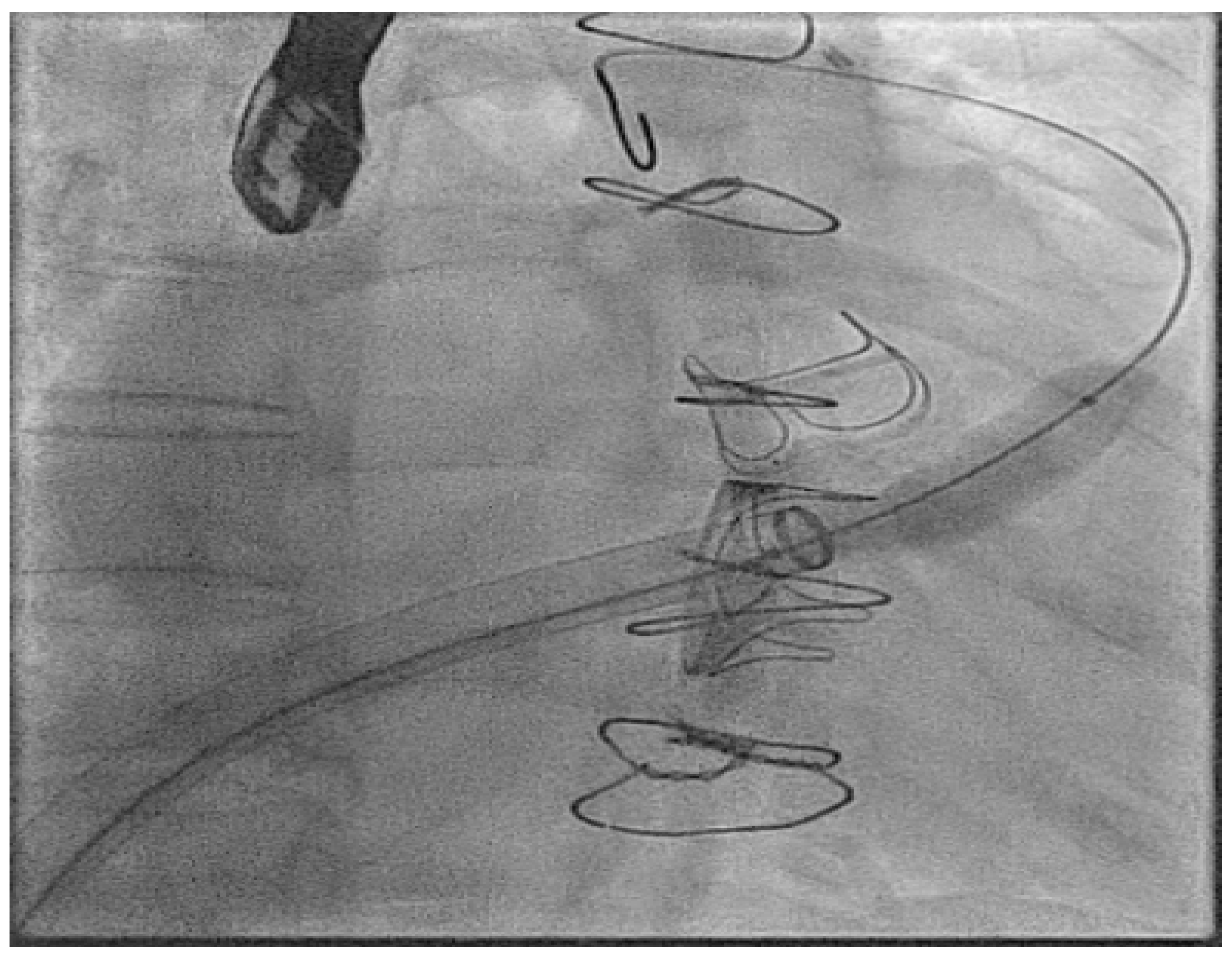

- Hayle, P.; Altayeb, F.; Hale, A.; Rao, A.; Ashrafi, R. Case report demonstrating novel approaches for leadless pacemaker implantation in the single ventricle heart. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2025, 9, ytaf146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

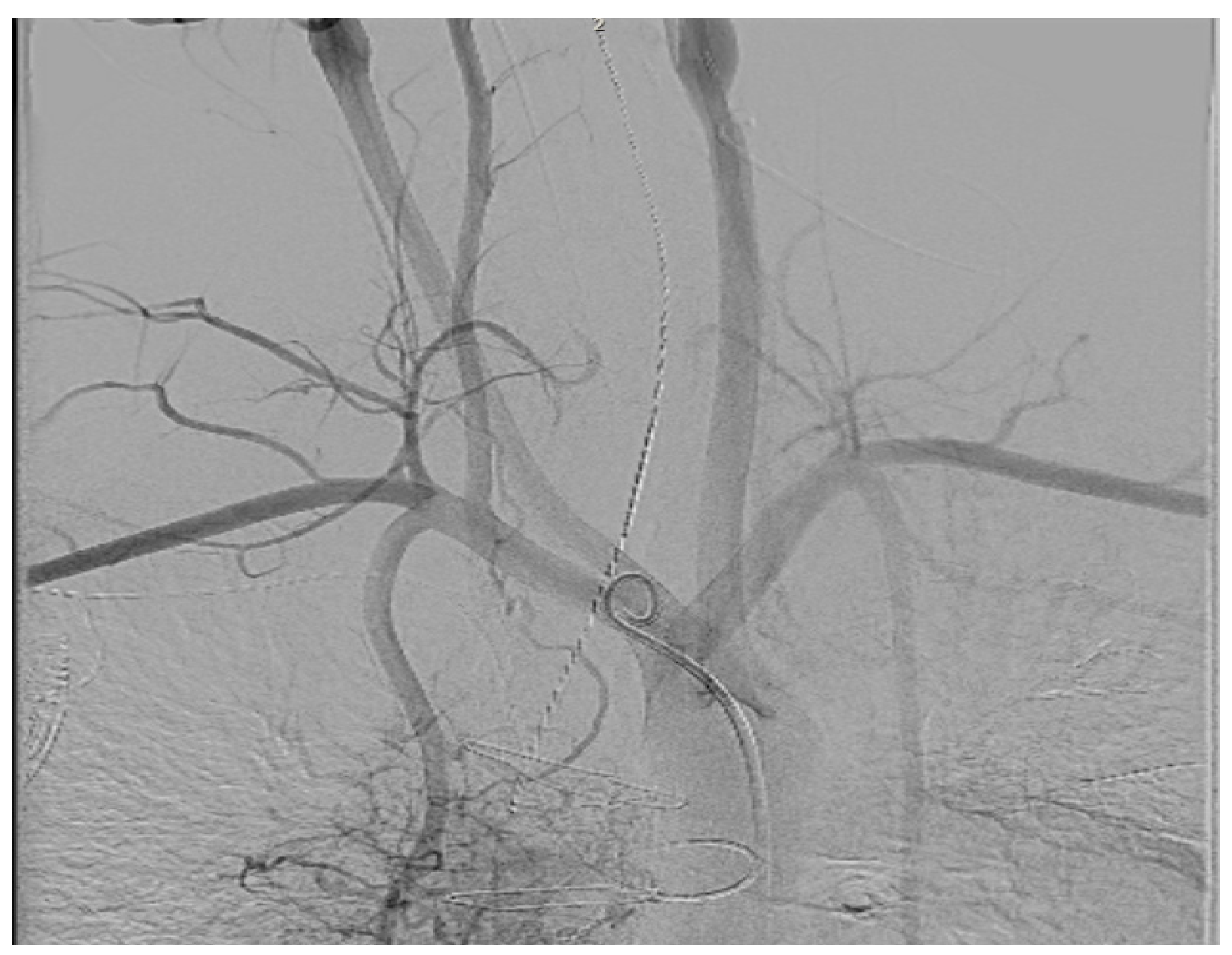

- Goulden, C.J.; Khanra, D.; Llewellyn, J.; Rao, A.; Evans, A.; Ashrafi, R. Novel approaches for leadless pacemaker implantation in the extra-cardiac Fontan cohort: Options to avoid leaded systems or epicardial pacing. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2023, 34, 2386–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A.; Jabeur, M.; Jacon, P.; Rinaldi, C.A.; Leclercq, C.; Rovaris, G.; Arnold, M.; Venier, S.; Neuzil, P.; Defaye, P. European experience with a first totally leadless cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker system. Europace 2020, 23, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Micra VR | Micra AV | Aveir AR | Aveir VR | Empower | EBRWISE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (mm) | 25.9 | 25.9 | 32 | 38 | 31.9 | 9.1 |

| Weight (g) | 2 | 2 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2 | 1.26 |

| Width (mm) | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Fixation | Passive tine | Passive tine | Active helix | Active helix | Passive tine | Active spike |

| Sensor | Accelerometer | Accelerometer | Temperature | Temperature | Accelerometer | N/A |

| Delivery catheter French size | 23 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 21 | 12 |

| Maximum mode | VVIR | VDD | AAIR | VVIR | VVIR | BIVP |

| Co-implant | No | No | Can be DR | Can be DR | With S-ICD | Mandatory |

| Designed to retrieve | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Battery projected maximum | 16 yrs | 16 yrs | 10 yrs | 20 yrs | 10 yrs | 4.5 yrs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rao, A.; Hughes, E.; Prica, M.; Raza, S.; Saber, M.; Ashrafi, R. Leadless Pacemakers in Complex Congenital Heart Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238560

Rao A, Hughes E, Prica M, Raza S, Saber M, Ashrafi R. Leadless Pacemakers in Complex Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238560

Chicago/Turabian StyleRao, Archana, Elen Hughes, Milos Prica, Sadaf Raza, Mohammed Saber, and Reza Ashrafi. 2025. "Leadless Pacemakers in Complex Congenital Heart Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238560

APA StyleRao, A., Hughes, E., Prica, M., Raza, S., Saber, M., & Ashrafi, R. (2025). Leadless Pacemakers in Complex Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238560