UV-C Light-Based Decontamination of Transvaginal Ultrasound Transducer: An Effective and Fast Way for Patient Safety in Gynecology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Their Preparation

- 1.

- Clinical bacterial strains of S. aureus, S. haemolyticus, S. agalactiae, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa used in the study came from the collection of the Department of Microbiology of the Jagiellonian University Medical College, including strains isolated in 2008–2016 from infections of pregnant or postpartum patients;

- 2.

- The reference strain Candida albicans ATCC 10231 (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was used as a control;

- 3.

- The reference strain T. vaginalis ATCC 30001TM (Manassas, VA, USA) was used a control.

- S. agalactiae: Columbia blood agar and TSA (Tryptic-Soy Agar) for other bacteria;

- Candida albicans: Sabourauda agar;

- T. vaginalis: Diamond liquid medium supplemented with bovine serum and antibiotics (1:1 penicillin-streptomycin mixture).

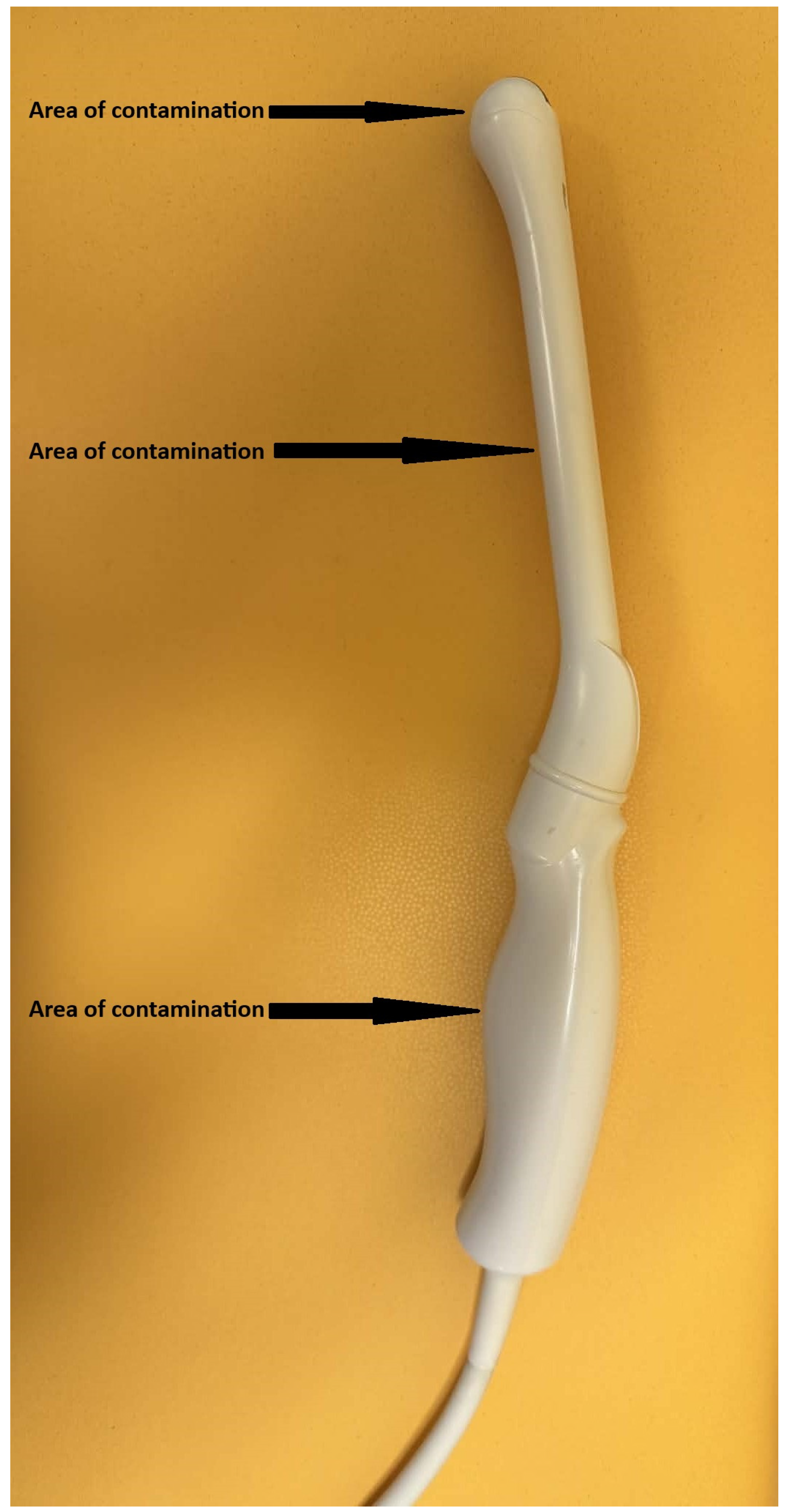

2.2. Probe Contamination and Disinfection Procedure

2.3. Disinfection Procedure

2.4. Determination of Bacterial and Fungal Suspension Density

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendling, W. Vaginal Microbiota. In Microbiota of the Human Body; Schwiertz, A., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 902, pp. 83–93. ISBN 978-3-319-31246-0. [Google Scholar]

- Deidda, F.; Amoruso, A.; Allesina, S.; Pane, M.; Graziano, T.; Del Piano, M.; Mogna, L. In Vitro Activity of Lactobacillus fermentum LF5 Against Different Candida Species and Gardnerella vaginalis?: A New Perspective to Approach Mixed Vaginal Infections? J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, S168–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, V.K.; Culhane, J.F.; Hitti, J.; Rauh, V.A.; McCollum, K.F.; Agnew, K.J. Relative Performance of Three Methods for Diagnosing Bacterial Vaginosis during Pregnancy. Matern. Child Health J. 2007, 11, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onderdonk, A.B.; Delaney, M.L.; Fichorova, R.N. The Human Microbiome during Bacterial Vaginosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitew, A.; Abebaw, Y.; Bekele, D.; Mihret, A. Prevalence of Bacterial Vaginosis and Associated Risk Factors among Women Complaining of Genital Tract Infection. Int. J. Microbiol. 2017, 2017, 4919404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, E.; Fredricks, D. Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacteria. In Molecular Medical Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1487–1496. ISBN 978-0-12-397169-2. [Google Scholar]

- Harfouche, M.; Gherbi, W.S.; Alareeki, A.; Alaama, A.S.; Hermez, J.G.; Smolak, A.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Epidemiology of Trichomonas vaginalis Infection in the Middle East and North Africa: Systematic Review, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Regressions. eBioMedicine 2024, 106, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerwen, O.T.; Opsteen, S.A.; Graves, K.J.; Muzny, C.A. Trichomoniasis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 37, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerwen, O.T.; Camino, A.F.; Sharma, J.; Kissinger, P.J.; Muzny, C.A. Epidemiology, Natural History, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis in Men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Burke, P.; Smalley, H.; Hobbs, G. Trichomonas vaginalis: Clinical Relevance, Pathogenicity and Diagnosis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 42, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappenfield, E.; Jamieson, D.J.; Kourtis, A.P. Pregnancy and Susceptibility to Infectious Diseases. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 2013, 752852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnarr, J.; Smaill, F. Asymptomatic Bacteriuria and Symptomatic Urinary Tract Infections in Pregnancy. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 38, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnota, W.; Mucha, D.; Mucha, J. Zakażenia Perinatalne Paciorkowcami Grupy B a Powikłania u Noworodków. Doświadczenia Własne. Ginekol. Perinatol. Prakt. 2017, 2, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bayó, M.; Berlanga, M.; Agut, M. Vaginal Microbiota in Healthy Pregnant Women and Prenatal Screening of Group B Streptococci (GBS). Int. Microbiol. 2002, 5, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielczarek, E.; Blaszkowska, J. Trichomonas vaginalis: Pathogenicity and Potential Role in Human Reproductive Failure. Infection 2016, 44, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, M.J.; Park, S.C.; Mathers, A.; Parikh, H.; Glowicz, J.; Dar, D.; Nabili, M.; LiPuma, J.J.; Bumford, A.; Pettengill, M.A.; et al. Outbreak of Burkholderia stabilis Infections Associated with Contaminated Nonsterile, Multiuse Ultrasound Gel—10 States, May–September 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, T.D.; Zimmerman, J.J. Ultraviolet Irradiation and the Mechanisms Underlying Its Inactivation of Infectious Agents. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2011, 12, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 734. The Role of Transvaginal Ultrasonography in Evaluating the Endometrium of Women With Postmenopausal Bleeding. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e124–e129. [CrossRef]

- Souli, M.; Galani, I.; Plachouras, D.; Panagea, T.; Armaganidis, A.; Petrikkos, G.; Giamarellou, H. Antimicrobial Activity of Copper Surfaces against Carbapenemase-Producing Contemporary Gram-Negative Clinical Isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oie, S.; Hosokawa, I.; Kamiya, A. Contamination of Room Door Handles by Methicillin-Sensitive/Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 2002, 51, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, A.; Chmielarczyk, A.; Romaniszyn, D.; Sroka-Oleksiak, A.; Bulanda, M.; Walkowicz, M.; Osuch, P.; Knych, T. Antimicrobial Properties of Selected Copper Alloys on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in Different Simulations of Environmental Conditions: With vs. without Organic Contamination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, A.; Chmielarczyk, A.; Romaniszyn, D.; Bulanda, M.; Walkowicz, M.; Osuch, P.; Knych, T. Antibiotic Resistance, Ability to Form Biofilm and Susceptibility to Copper Alloys of Selected Staphylococcal Strains Isolated from Touch Surfaces in Polish Hospital Wards. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, A.; Pioskowik, A.; Herrles, L.; Datta, T.; Krzyściak, P.; Jachowicz-Matczak, E.; Siewierski, T.; Walkowicz, M.; Chmielarczyk, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of UV-C Radiation in Eliminating Clostridioides Difficile from Touch Surfaces Under Laboratory Conditions. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, E. Schallkopfhygiene-ein unterschätztes Thema? Ultraschall Med. Eur. J. Ultrasound 2005, 26, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-H.; Wu, U.-I.; Tai, H.-M.; Sheng, W.-H. Effectiveness of an Ultraviolet-C Disinfection System for Reduction of Healthcare-Associated Pathogens. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.R.; Schweizer, M.L.; Edmond, M.B. No-Touch Disinfection Methods to Decrease Multidrug-Resistant Organism Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalouhi, G.E.; Salomon, L.J.; Marelle, P.; Bernard, J.P.; Ville, Y. Hygiène en échographie endocavitaire gynécologique et obstétricale en 2008. J. Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol. Reprod. 2009, 38, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, A.C.; Miller, W.C.; Hobbs, M.M.; Schwebke, J.R.; Leone, P.A.; Swygard, H.; Atashili, J.; Cohen, M.S. Trichomonas vaginalis Infection in Male Sexual Partners: Implications for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, Z.; Yassin, M. Role of Ultraviolet (UV) Disinfection in Infection Control and Environmental Cleaning. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2013, 13, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microorganism | Density of Culture [CFU/mL] | Reduction in Density of Culture [%] | Log * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | After Procedures | |||||||

| Control | Transduce | Handle | Transduce | Handle | Transduce and Handle | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4.20 × 107 | 1.02 × 106 | 3.33 × 101 | 5.00 × 101 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5 |

| Staphylococcus haemolitycus | 2.69 × 107 | 1.10 × 106 | 4.00 × 101 | 3.33 × 101 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 6.90 × 107 | 5.50 × 106 | 6.67 × 100 | 6.67 × 100 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 6 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 1.50 × 107 | 7.70 × 105 | 1.00 × 101 | 3.33 × 100 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 8.60 × 106 | 5.60 × 105 | 6.67 × 100 | 3.33 × 100 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1.60 × 108 | 7.25 × 105 | 2.67 × 101 | 0.00 × 100 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1.39 × 108 | 4.40 × 105 | 7.00 × 101 | 3.33 × 100 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 4 |

| Escherichia coli | 3.75 × 107 | 2.85 × 105 | 0.00 × 100 | 0.00 × 100 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 4 |

| Candida albicans | 5.00 × 106 | 9.50 × 104 | 0.00 × 100 | 0.00 × 100 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 4 |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Density of culture [protozoan cell count/mL] | Reduction in density of culture [%] | Log * | |||||

| 7.19 × 106 | 8.60 × 105 | 1.55 × 105 | n.a. | 82.4 | n.a. | 82.4 | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siewierski, T.; Fibiger, G.; Różańska, A.; Pietrzyk, A.; Jachowicz-Matczak, E.; Romaniszyn, D.; Wójkowska-Mach, J. UV-C Light-Based Decontamination of Transvaginal Ultrasound Transducer: An Effective and Fast Way for Patient Safety in Gynecology. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238561

Siewierski T, Fibiger G, Różańska A, Pietrzyk A, Jachowicz-Matczak E, Romaniszyn D, Wójkowska-Mach J. UV-C Light-Based Decontamination of Transvaginal Ultrasound Transducer: An Effective and Fast Way for Patient Safety in Gynecology. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238561

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiewierski, Tomasz, Grzegorz Fibiger, Anna Różańska, Agata Pietrzyk, Estera Jachowicz-Matczak, Dorota Romaniszyn, and Jadwiga Wójkowska-Mach. 2025. "UV-C Light-Based Decontamination of Transvaginal Ultrasound Transducer: An Effective and Fast Way for Patient Safety in Gynecology" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238561

APA StyleSiewierski, T., Fibiger, G., Różańska, A., Pietrzyk, A., Jachowicz-Matczak, E., Romaniszyn, D., & Wójkowska-Mach, J. (2025). UV-C Light-Based Decontamination of Transvaginal Ultrasound Transducer: An Effective and Fast Way for Patient Safety in Gynecology. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238561