Challenges and Management Outcomes of Osteoarticular Infections in Adult Sickle Cell Disease Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Settings, and Population

- Adults aged 16 years or older.

- Confirmed SCD diagnosis through hemoglobin electrophoresis.

- Admitted with a primary diagnosis of osteoarticular infection or admitted for other reasons but confirmed to have an osteoarticular infection.

2.2. Definitions

- High clinical suspicion: Persistent fever, localized pain—especially in long bones—along with signs beyond a typical Vaso-occlusive crisis (VCO), such as swelling, redness, warmth, ulceration, discharge, a palpable fluctuant mass, significant effusion, or draining sinus tract. Also, consider a prolonged illness course with symptoms lasting over one week.

- Supportive laboratory findings: leukocytosis elevated CRP, thrombocytosis, or increased alkaline phosphatase.

- Positive imaging studies: In plain X-ray (periosteal elevation, lytic or destructive lesions, new bone formation, sequestrum, sclerosis, or medullary infarction) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (soft tissue edema, abscess, or phlegmon, cortical destruction, rim-enhancing fluid collections, sinus tracts, or bone marrow edema with focal fluid collection) findings.

- Microbiological evidence: Positive blood cultures or positive cultures from bone or joint aspirates or biopsies.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

3.2. Laboratory and Microbiological Results

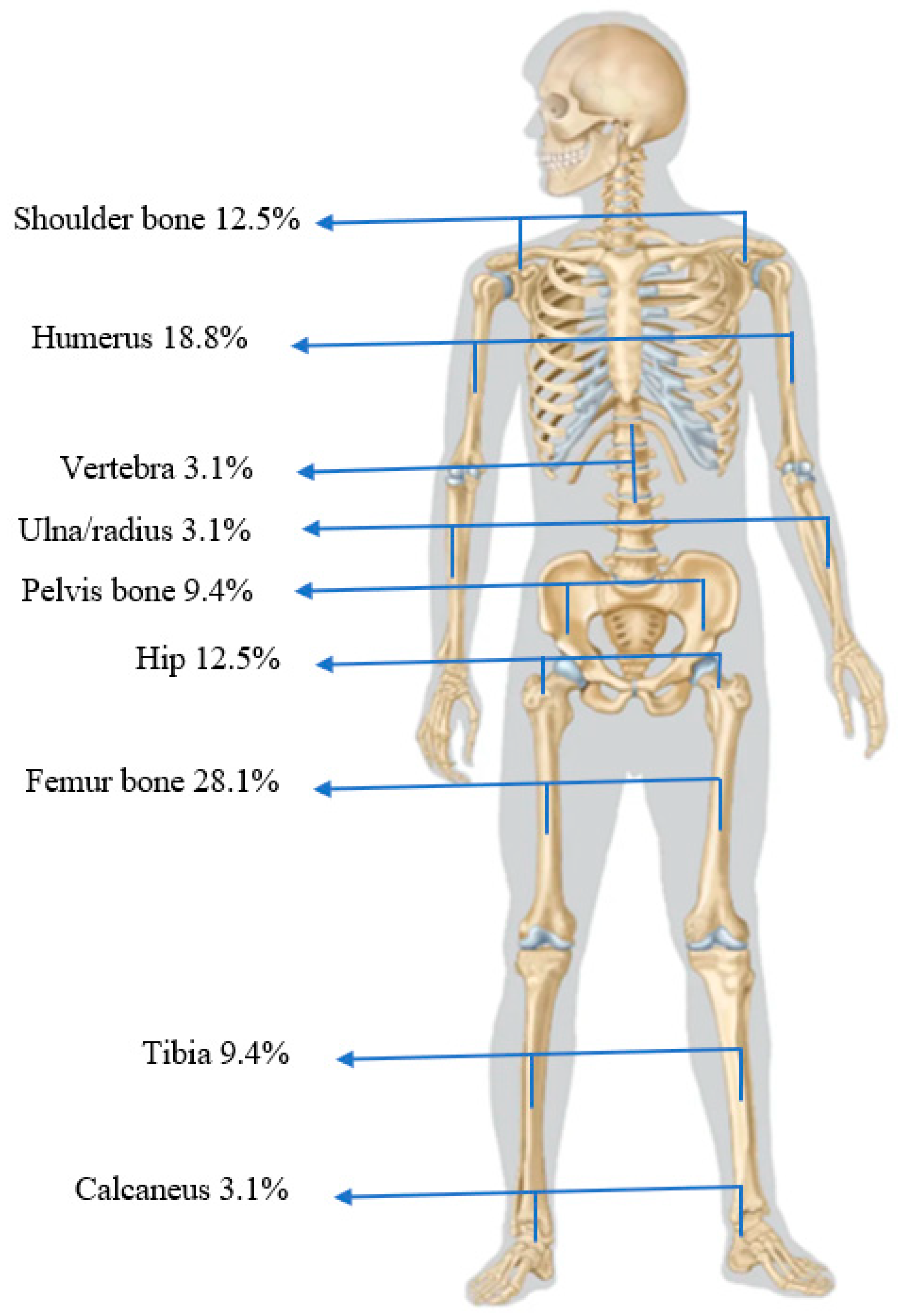

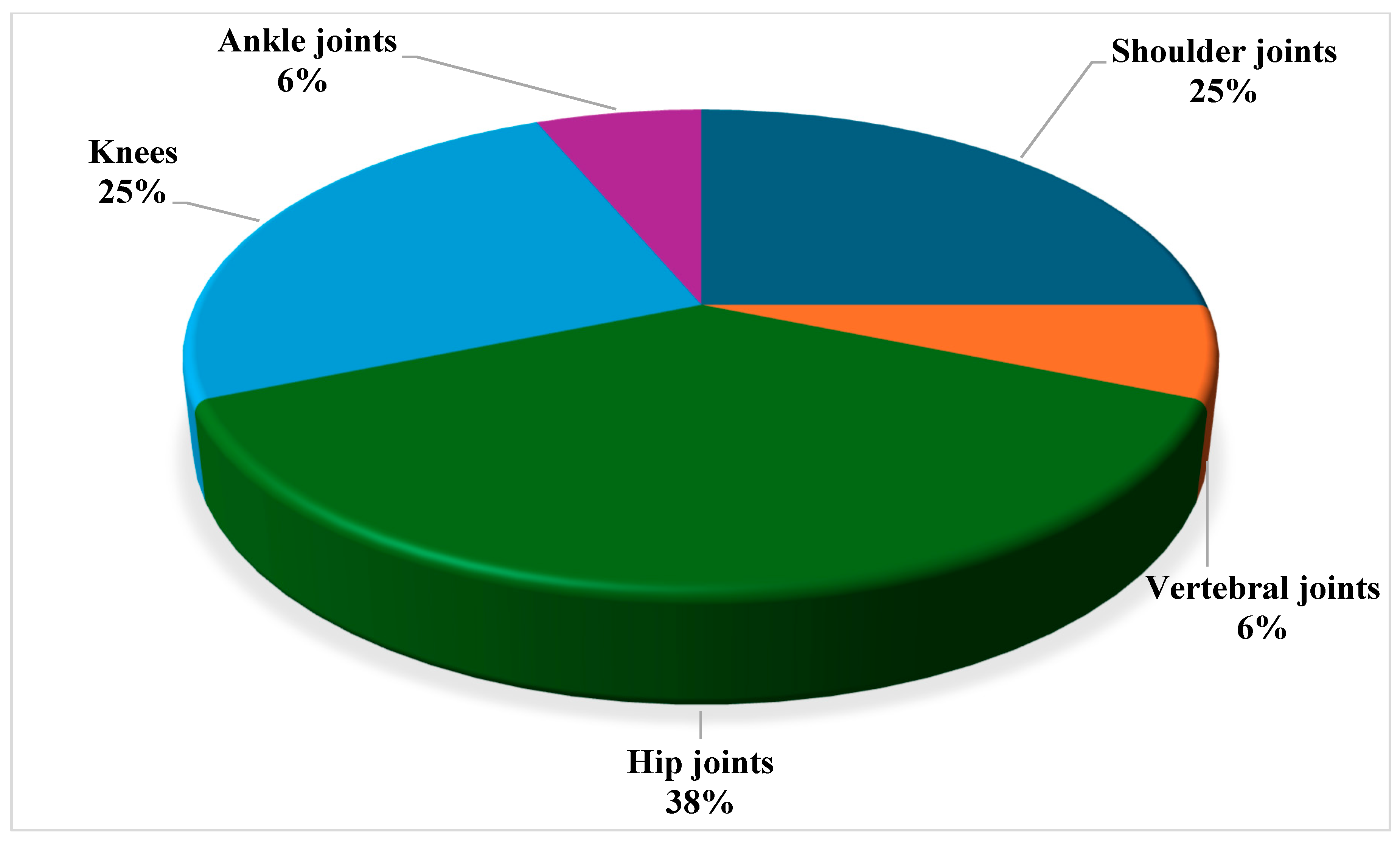

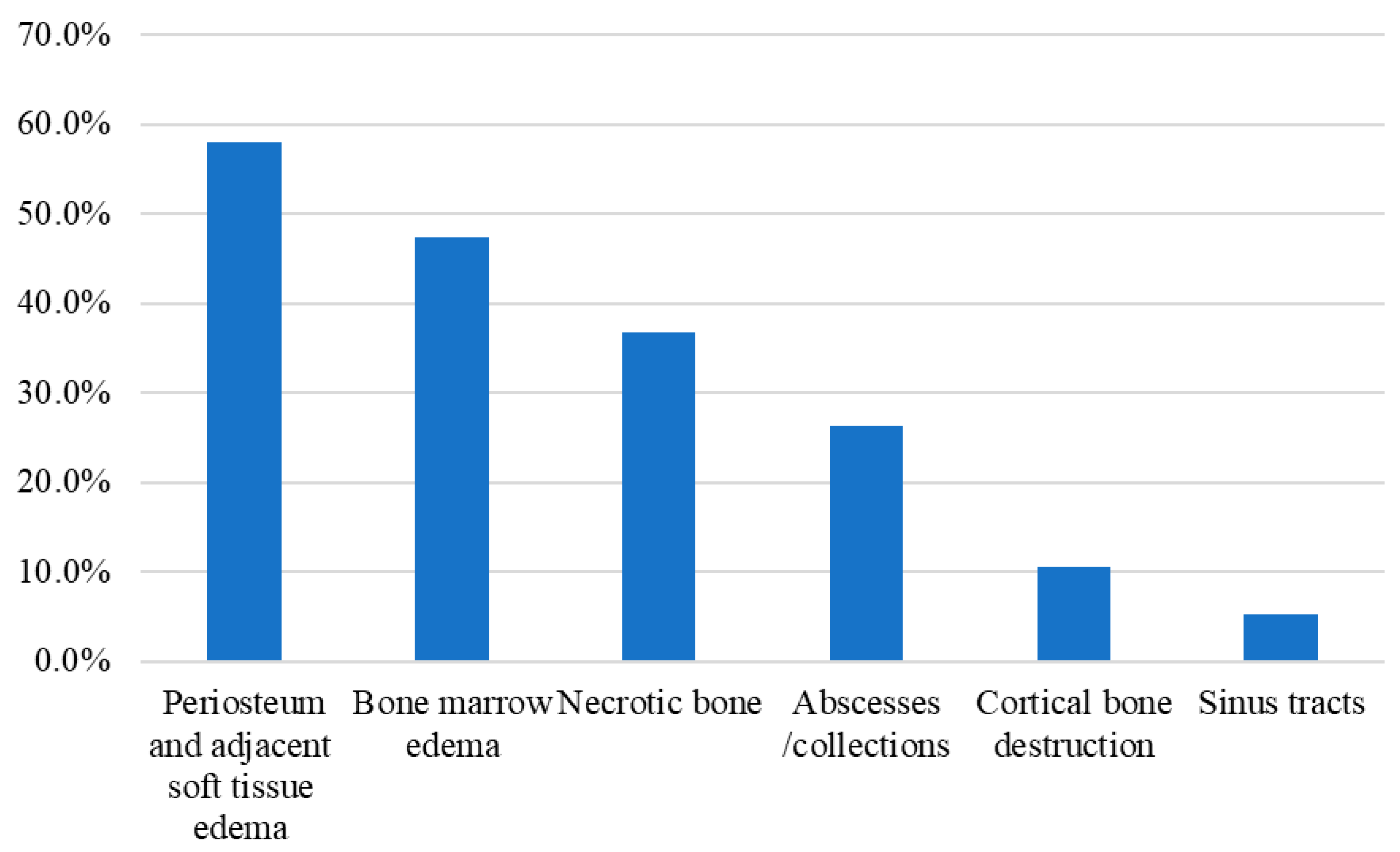

3.3. Radiological Findings

3.4. Management and Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBC | Complete Blood Count |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ED | Emergency department |

| G6PD | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LFT | Liver Function Tests |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OM | Osteomyelitis |

| SCA | Sickle cell Anemia |

| SCD | Sickle cell disease |

| VOC | Vaso-occlusive crisis |

References

- GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence and Mortality Burden of Sickle Cell Disease, 2000–2021: A Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e585–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlet, J.-B. Epidemiology of sickle cell disease in France and in the world. Rev. Prat. 2023, 73, 500–504. [Google Scholar]

- Jastaniah, W. Epidemiology of Sickle Cell Disease in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2011, 31, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, A.H.; Ahmed, H.A.; Qaisaruddin, S.; Al-Jam’a, A.; Elbashier, A.M.; Al-Dabbous, I. Osteomyelitis and Septic Arthritis in Sickle Cell Disease in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Int. Orthop. 1992, 16, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif, M.; Robinson, J.; Abdulbaqi, M.; Aghbari, M.; Al Noaim, K.; Alabdulqader, M. Prevalence of Serious Bacterial Infections in Children with Sickle Cell Disease at King Abdulaziz Hospital, Al Ahsa. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 13, e2021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Carvajal, A.J.; Agreda-Pérez, L.H. Antibiotics for Treating Osteomyelitis in People with Sickle Cell Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2021, CD007175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Agarwal, A.K.; Edomwonyi, E.O.; Vijay, V. Musculoskeletal Manifestations of Sickle Cell Disease: A Review. Cureus 2015, 7, e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, D.P.; Waldvogel, F.A. Osteomyelitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaraju, V.; Harwani, A.; Partovi, S.; Bhojwani, N.; Garg, V.; Ayyappan, S.; Kosmas, C.; Robbin, M. Imaging of Musculoskeletal Manifestations in Sickle Cell Disease Patients. Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 20160130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Junior, G.B.; Daher, E.D.F.; da Rocha, F.A.C. Osteoarticular Involvement in Sickle Cell Disease. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2012, 34, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, M.H.; Friedlaender, G.E.; Marsh, J.S. Orthopaedic Manifestations of Sickle-Cell Disease. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1990, 63, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Banza, M.I.; Kapessa, N.D.; Mukakala, A.K.; Ngoie, C.N.; N Dwala, Y.T.B.; Cabala, V.D.P.K.; Kasanga, T.K.; Unen, E.W. Osteoarticular infections in patients with sickle cell disease in Lubumbashi: Epidemiological study focusing on etiology and management. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Ali, M.; Geeranavar, S.S.; As-Suhaimi, S. Orthopaedic Complications in Sickle Cell Disease: A Comparative Study from Two Regions in Saudi Arabia. Int. Orthop. 1992, 16, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scourfield, L.E.A.; Nardo-Marino, A.; Williams, T.N.; Rees, D.C. Infections in Sickle Cell Disease. Haematologica 2025, 110, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashkandi, D.A.; Hanafy, E.; Alotaibi, N.; Abuharfel, D.; Alnijaidi, A.; Banjar, A.M.; Abufara, F.; Riyad, S.; Alhalabi, M.; Alblowi, N. Indicators for Osteomyelitis in Children with Sickle Cell Disease Admitted with Vaso-Occlusive Crises. Cureus 2024, 16, e68265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.B.; Forsythe, D.A.; Bertrand, S.L.; Iwinski, H.J.; Steflik, D.E. Retrospective Review of Osteoarticular Infections in a Pediatric Sickle Cell Age Group. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2000, 20, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Ali, M. The Status of Acute Osteomyelitis in Sickle Cell Disease. A 15-Year Review. Int. Surg. 1998, 83, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bennett, O.M.; Namnyak, S.S. Bone and Joint Manifestations of Sickle Cell Anaemia. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1990, 72, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.L.; Sakamoto, K.M.; Johnson, E.E. Differentiating Osteomyelitis from Bone Infarction in Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2001, 17, 60–63; quiz 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannas, G.; Merazga, S.; Virot, E. Sickle Cell Disease and Infections in High- and Low-Income Countries. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, e2019042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallouh, A.; Talab, Y. Bone and Joint Infection in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1985, 5, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.J.; Glatt, A.E. Salmonella Osteomyelitis and Arthritis in Sickle Cell Disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1994, 24, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyokunnu, A.A.; Hendrickse, R.G. Salmonella Osteomyelitis in Childhood. A Report of 63 Cases Seen in Nigerian Children of Whom 57 Had Sickle Cell Anaemia. Arch. Dis. Child. 1980, 55, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farii, H.; Zhou, S.; Albers, A. Management of Osteomyelitis in Sickle Cell Disease: Review Article. JAAOS Glob. Res. Rev. 2020, 4, e20.00002-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwadiaro, H.; Ugwu, B.; Legbo, J. Chronic Osteoyelitis in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. East Afr. Med. J. 2009, 77, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.M.; Yee, M.E.; Maillis, A.; Lai, K.; Bakshi, N.; Rostad, B.S.; Jerris, R.C.; Lane, P.A.; Yildirim, I. Microbiology and Radiographic Features of Osteomyelitis in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epps, C.H.; Bryant, D.D.; Coles, M.J.; Castro, O. Osteomyelitis in Patients Who Have Sickle-Cell Disease. Diagnosis and Management. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1991, 73, 1281–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Ali; Sankaran-Kutty; Kutty, K. Recent Observations on Osteomyelitis in Sickle-Cell Disease. Int. Orthop. 1985, 9, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegeman, E.M.; Bates, T.; Lynch, T.; Schmitz, M.R. Osteomyelitis in Sickle Cell Anemia: Does Age Predict Risk of Salmonella Infection? Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, e262–e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbashier, A.M.; Al-Salem, A.H.; Aljama, A. Salmonella as a Causative Organism of Various Infections in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Ann. Saudi Med. 2003, 23, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalife, S.; Hanna-Wakim, R.; Ahmad, R.; Haidar, R.; Makhoul, P.G.; Khoury, N.; Dbaibo, G.; Abboud, M.R. Emergence of Gram-negative Organisms as the Cause of Infections in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.; Sawhney, S.; Rizvi, S.G. Acute Bone Crises in Sickle Cell Disease: The T1 Fat-Saturated Sequence in Differentiation of Acute Bone Infarcts from Acute Osteomyelitis. Clin. Radiol. 2008, 63, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernigou, P.; Daltro, G.; Flouzat-Lachaniette, C.-H.; Roussignol, X.; Poignard, A. Septic Arthritis in Adults with Sickle Cell Disease Often Is Associated with Osteomyelitis or Osteonecrosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 1676–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisman, J.K.; Nickel, R.S.; Darbari, D.S.; Hanisch, B.R.; Diab, Y.A. Characteristics and Outcomes of Osteomyelitis in Children with Sickle Cell Disease: A 10-year Single-center Experience. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umans, H.; Haramati, N.; Flusser, G. The Diagnostic Role of Gadolinium Enhanced MRI in Distinguishing between Acute Medullary Bone Infarct and Osteomyelitis. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2000, 18, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifai, A.; Nyman, R. Scintigraphy and Ultrasonography in Differentiating Osteomyelitis from Bone Infarction in Sickle Cell Disease. Acta Radiol. 1997, 38, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Carvajal, A.J.; Agreda-Pérez, L.H. Antibiotics for Treating Osteomyelitis in People with Sickle Cell Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2021, CD007175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; DeBaun, M.R. Acute and Chronic Bone Complications of Sickle Cell Disease. 2025. Available online: https://www-uptodate-com.library.iau.edu.sa/contents/acute-and-chronic-bone-complications-of-sickle-cell-disease? (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Salmonella Typhi and Non-Typhi in a Hospital in Eastern Saudi Arabia. J. Chemother. 2007, 19, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.A.; Neyaz, L.A.; Malak, H.A.; Alshehri, W.A.; Elbanna, K.; Organji, S.R.; Asiri, F.H.; Aldosari, M.S.; Abulreesh, H.H. Diversity and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Clinical and Environmental Salmonella Enterica Serovars in Western Saudi Arabia. Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.; Palladino, V.; Lassandro, G.; Spina, S.; Del Vecchio, G.C. An Epidemic of Parvovirus B19-Induced Aplastic Crises in Pediatric Patients with Hereditary Spherocytosis Following the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Children 2025, 12, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwazzeh, M.J.; Telmesani, M.L.; AlEnazi, S.A.; Buohliqah, A.L.; Halawani, T.R.; Jatoi, N.A.; Subbarayalu, A.V.; Almuhanna, F.A. Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage and its association with COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 27, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bio-Demographics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 27 | 87.1% |

| Female | 4 | 12.9% |

| Age in years (Mean ± SD) | 26.55 ± 7.28 | |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 29 | 93.5% |

| Non-Saudi | 2 | 6.5% |

| SCA (homozygous patients) | 19 | 61.3% |

| SCD (heterozygous patients) | 12 | 38.7% |

| Number of yearly ED visits (Mean ± SD) | 5.48 ± 3.67 | |

| Number of yearly admissions (Mean ± SD) | 2.45 ± 1.50 | |

| Number of ICU admissions (Mean ± SD) | 1.12 ± 0.78 | |

| Co-morbidities | ||

| G6PD deficiency | 14 | 60.9% |

| β-thalassemia/α trait | 10 | 30.4% |

| Bronchial asthma | 4 | 17.4% |

| Avascular necrosis | 5 | 13.0% |

| Thromboembolic events | 3 | 8.7% |

| Hypertension | 2 | 8.7% |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2 | 8.7% |

| Osteoarticular infection type | ||

| Acute osteomyelitis | 15 | 48.4% |

| Recurrent (acute) osteomyelitis | 3 | 9.7% |

| Chronic osteomyelitis | 13 | 41.9% |

| Joint involvement (arthritis) | 16 | 53.3% |

| Clinical manifestations | ||

| Localized Pain | 31 | 100.0% |

| Swelling | 31 | 100.0% |

| Redness | 11 | 35.5% |

| Hotness | 5 | 16.1% |

| Fever | 9 | 29.0% |

| Surgical splenectomy | 6 | 19.4% |

| Functional splenectomy | 13 | 41.9% |

| Onco-carbide (hydroxyurea) | 20 | 64.5% |

| Total (N = 31) | Suspected vs. Confirmed OM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected OM (N = 12) | Confirmed OM (N = 19) | |||

| Leukocytes count | 11.4 ± 5.2 | 13.27 ± 4.11 | 10.22 ± 5.63 | 0.117 |

| Neutrophils % | 61.0 ± 14.2 | 63.93 ± 15.21 | 56.25 ± 18.60 | 0.241 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.8 ± 1.6 | 8.79 ± 1.40 | 8.76 ± 1.84 | 0.951 |

| Hematocrit | 27.5% ± 3.7 | 28.08 ± 3.04 | 27.14 ± 4.23 | 0.507 |

| Platelet count | 399.5 ± 209.1 | 430.17 ± 220.03 | 380.20 ± 211.47 | 0.533 |

| Reticulocytes % | 6.7% ± 4.1 | 6.55 ± 3.49 | 6.85 ± 4.70 | 0.849 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 13.8 ± 9.7 | 12.57 ± 7.67 | 14.50 ± 11.23 | 0.607 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.5 ± 2.6 | 2.41 ± 1.33 | 2.49 ± 3.20 | 0.934 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.6 ± 2.3 | 1.64 ± 1.44 | 1.65 ± 2.81 | 0.992 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 157.5 ± 88.5 | 170.17 ± 99.52 | 149.53 ± 85.14 | 0.543 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 32.1 ± 16.1 | 39.33 ± 17.42 | 27.47 ± 14.23 | 0.047 * |

| Aspartate transferase (U/L) | 47.5 ± 32.2 | 59.17 ± 26.55 | 40.11 ± 34.66 | 0.115 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (U/L) | 456.1 ± 288.2 | 466.08 ± 242.17 | 449.79 ± 327.28 | 0.883 |

| Suspected vs. Confirmed OM | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected OM (N = 12) | Confirmed OM (N = 19) | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 11 | 91.7% | 16 | 84.2% | 0.546 |

| Female | 1 | 8.3% | 3 | 15.8% | |

| Age in years (Mean ± SD) | 28.3 ± 9.8 | 25.5 ± 5.4 | 0.224 | ||

| SCA (homozygous patients) | 8 | 66.7% | 11 | 57.9% | 0.625 |

| SCD (heterozygous patients) | 4 | 33.3% | 8 | 42.1% | 0.625 |

| Number of yearly ED visits (Mean ± SD) | 6.00 ± 4.82 | 5.16 ± 2.95 | 0.550 | ||

| Number of yearly admissions (Mean ± SD) | 2.58 ± 1.38 | 2.37 ± 1.64 | 0.709 | ||

| Number of ICU admissions (Mean ± SD) | 1.17 ± 1.19 | 0.68 ± 1.11 | 0.261 | ||

| Recurrence of osteoarticular infections | |||||

| One time | 10 | 83.3% | 12 | 63.2% | 0.430 |

| Two times | 3 | 16.7% | 9 | 31.6% | |

| Three times | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | |

| Co-morbidities | |||||

| G6PD deficiency | 3 | 25.0% | 10 | 52.6% | 0.129 |

| β-thalassemia/α trait | 3 | 25.0% | 7 | 36.8% | 0.492 |

| Bronchial asthma | 2 | 16.7% | 2 | 10.5% | 0.619 |

| Avascular necrosis | 1 | 8.3% | 4 | 21.1% | 0.348 |

| Clinical manifestations | |||||

| Localized pain | 12 | 100.0% | 19 | 100.0% | - |

| Swelling | 12 | 100.0% | 19 | 100.0% | - |

| Redness | 6 | 50.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 0.179 |

| Hotness | 3 | 25.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 0.286 |

| Fever | 5 | 41.7% | 4 | 21.1% | 0.218 |

| MRI abnormalities | |||||

| Periosteum and adjacent soft tissue edema | 4 | 33.3% | 7 | 36.8% | 0.842 |

| Bone marrow edema | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 47.4% | 0.005 * |

| Cortical bone destruction | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 0.245 |

| Necrotic bone | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 36.8% | 0.017 * |

| Sinus tracts | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 0.419 |

| Abscesses/collections | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 0.052 |

| Surgical splenectomy | 3 | 25.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 0.527 |

| Functional splenectomy | 3 | 25.0% | 10 | 52.6% | 0.130 |

| Onco-carbide (hydroxyurea) | 6 | 50.0% | 14 | 73.7% | 0.180 |

| Antibiotic Combination Therapy | Treated Patients N (%) | Cured Patients N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Clindamycin + Ciprofloxacin | 22 (71.0%) | 21 (95.5%) |

| Clindamycin + Piperacillin/tazobactam | 5 (16.1%) | 5 (100%) |

| Clindamycin + Ceftriaxone | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (100%) |

| Cefazolin + Ciprofloxacin | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (100%) |

| Total | 31 (100%) | 30 (96.8%) |

| Antibiotic therapy duration in days * | 36.7 ± 21.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhajri, M.M.; Alwazzeh, M.J.; Almulhim, G.; Alsahlawi, A.; Alharbi, M.A.; Alotaibi, F.; Alanazi, B.S.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Aljabbari, F. Challenges and Management Outcomes of Osteoarticular Infections in Adult Sickle Cell Disease Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238542

Alhajri MM, Alwazzeh MJ, Almulhim G, Alsahlawi A, Alharbi MA, Alotaibi F, Alanazi BS, Alzahrani AS, Aljabbari F. Challenges and Management Outcomes of Osteoarticular Infections in Adult Sickle Cell Disease Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238542

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhajri, Mashael M., Marwan Jabr Alwazzeh, Ghayah Almulhim, Ahmed Alsahlawi, Mohammed A. Alharbi, Faleh Alotaibi, Bader Salamah Alanazi, Ahmed Salamah Alzahrani, and Fahad Aljabbari. 2025. "Challenges and Management Outcomes of Osteoarticular Infections in Adult Sickle Cell Disease Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238542

APA StyleAlhajri, M. M., Alwazzeh, M. J., Almulhim, G., Alsahlawi, A., Alharbi, M. A., Alotaibi, F., Alanazi, B. S., Alzahrani, A. S., & Aljabbari, F. (2025). Challenges and Management Outcomes of Osteoarticular Infections in Adult Sickle Cell Disease Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238542