Prognostic Factors in Salivary Gland Malignancies: A Multicenter Study of 229 Patients from the Polish Salivary Network Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Variables

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

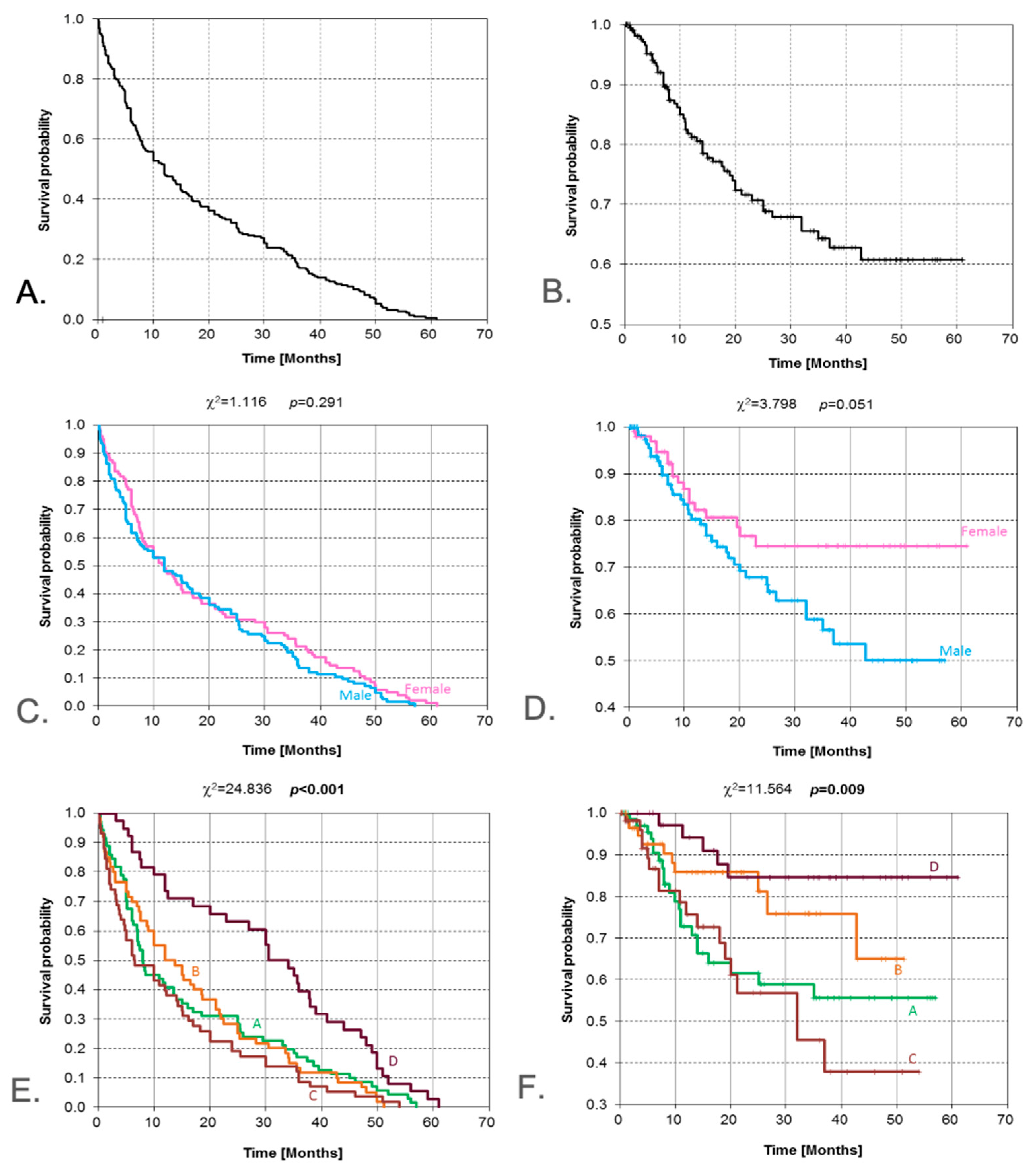

3.1. Gender

3.2. Place of Residence

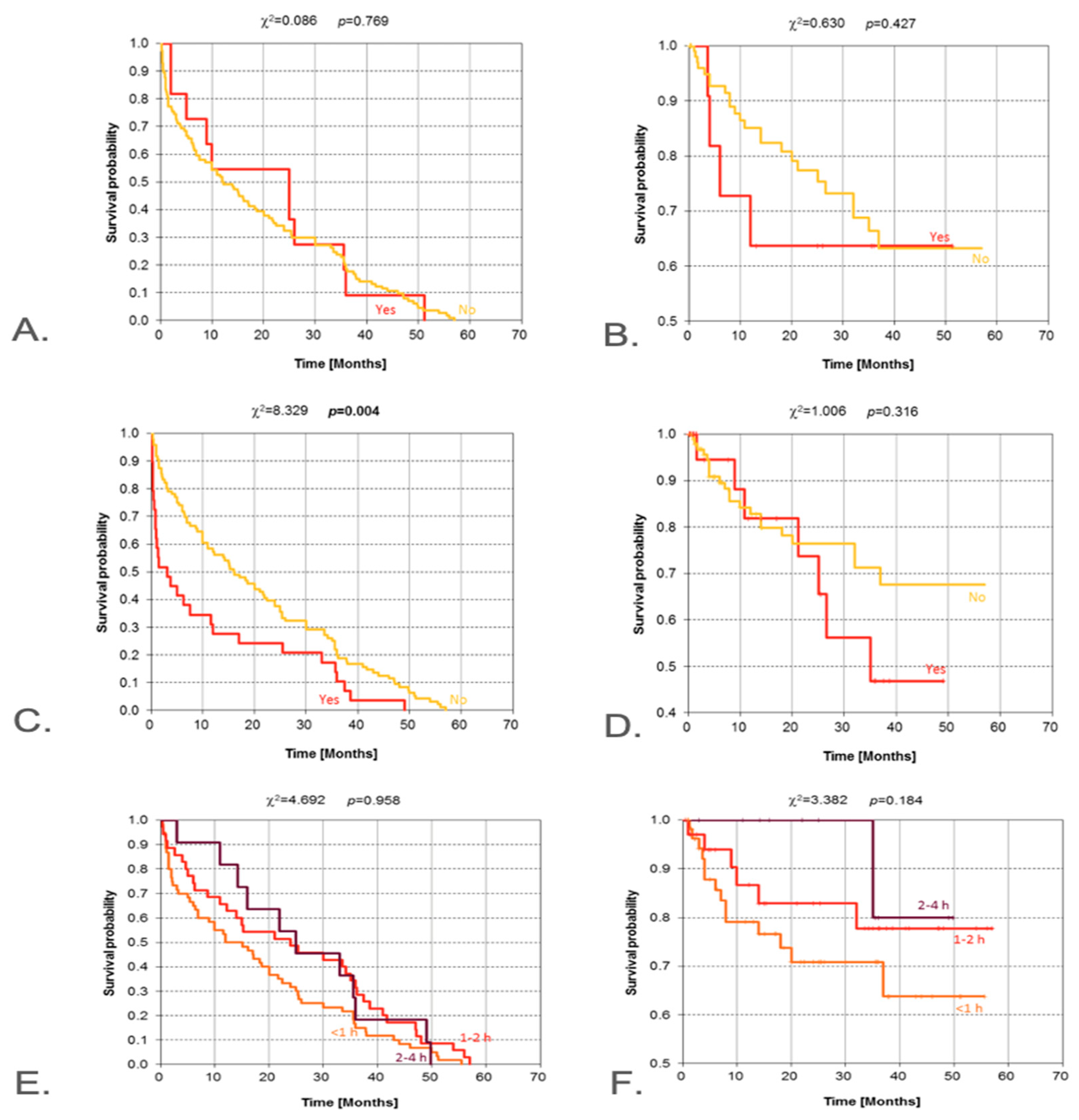

3.3. Exposures

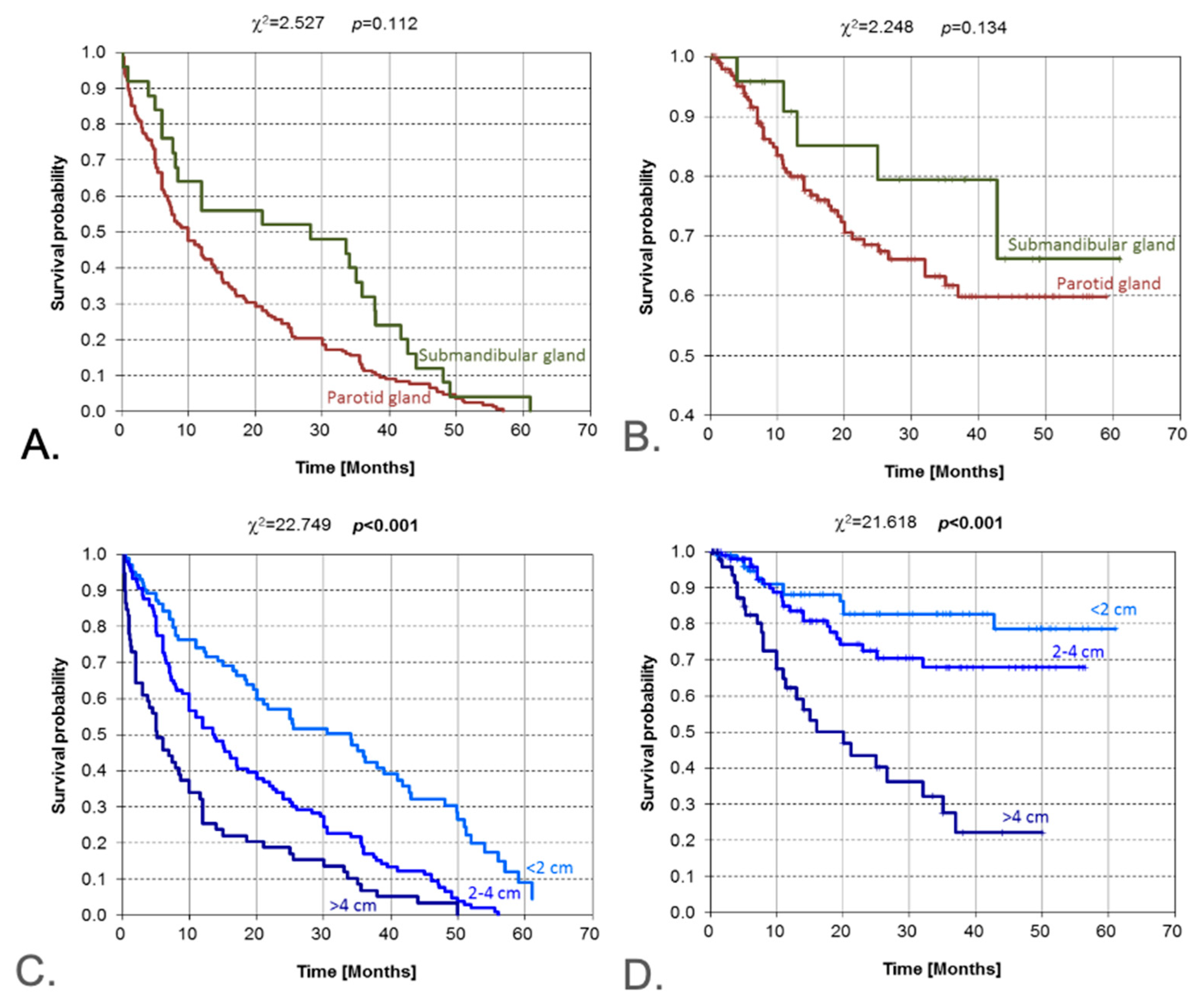

3.4. Tumor Location and Size

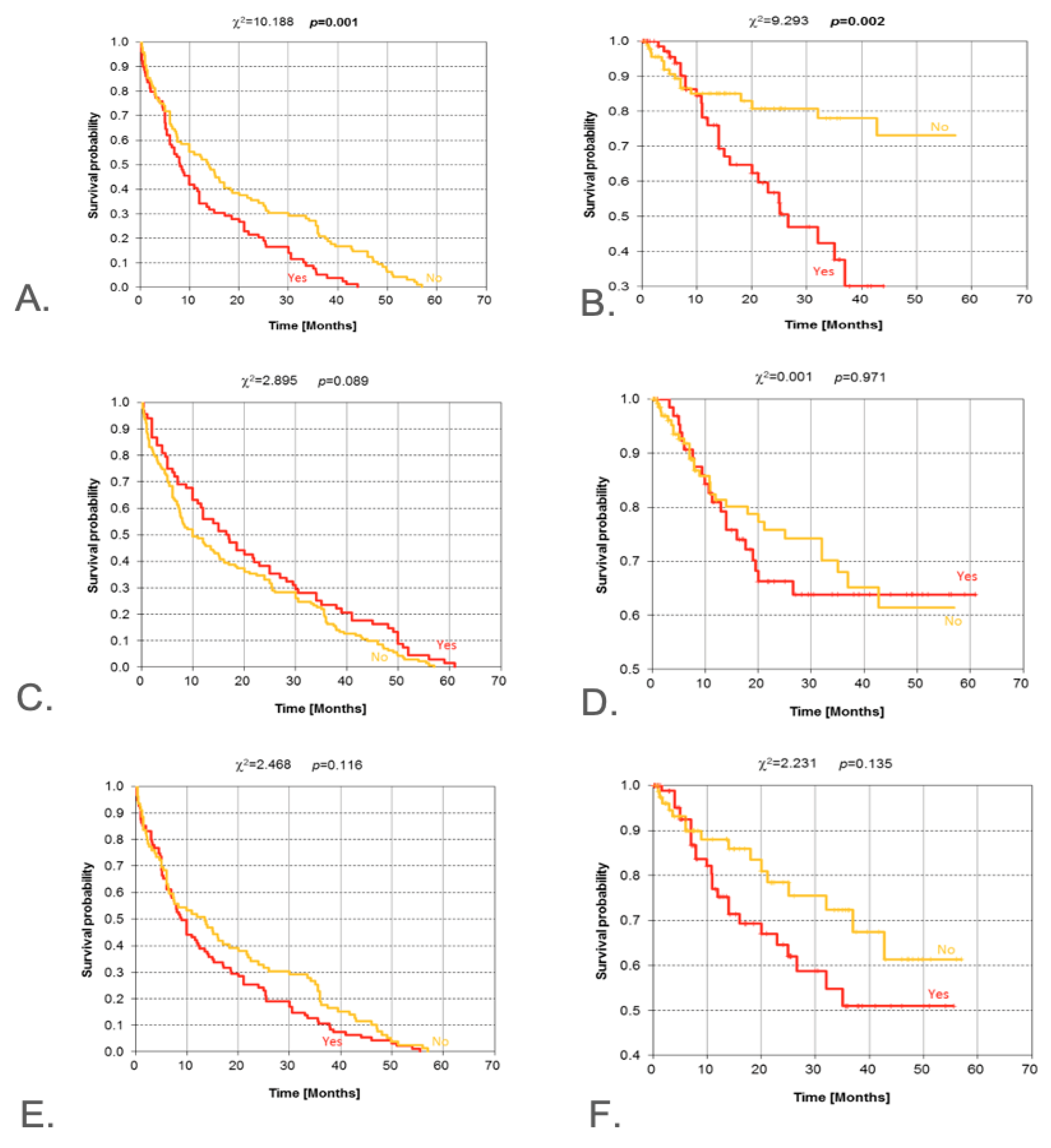

3.5. Clinical and Radiological Signs of Malignancy

3.6. Tumor Advancement

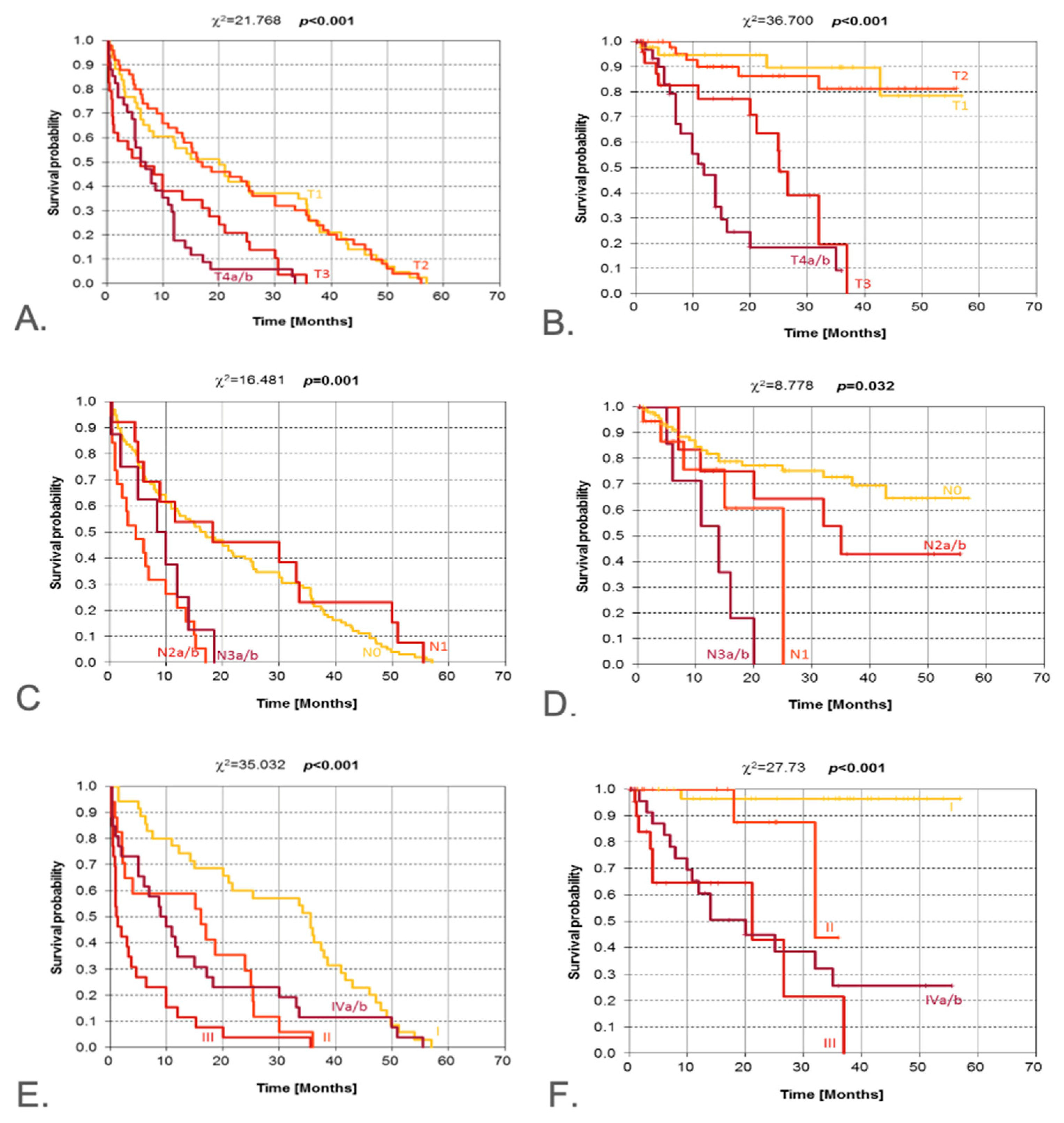

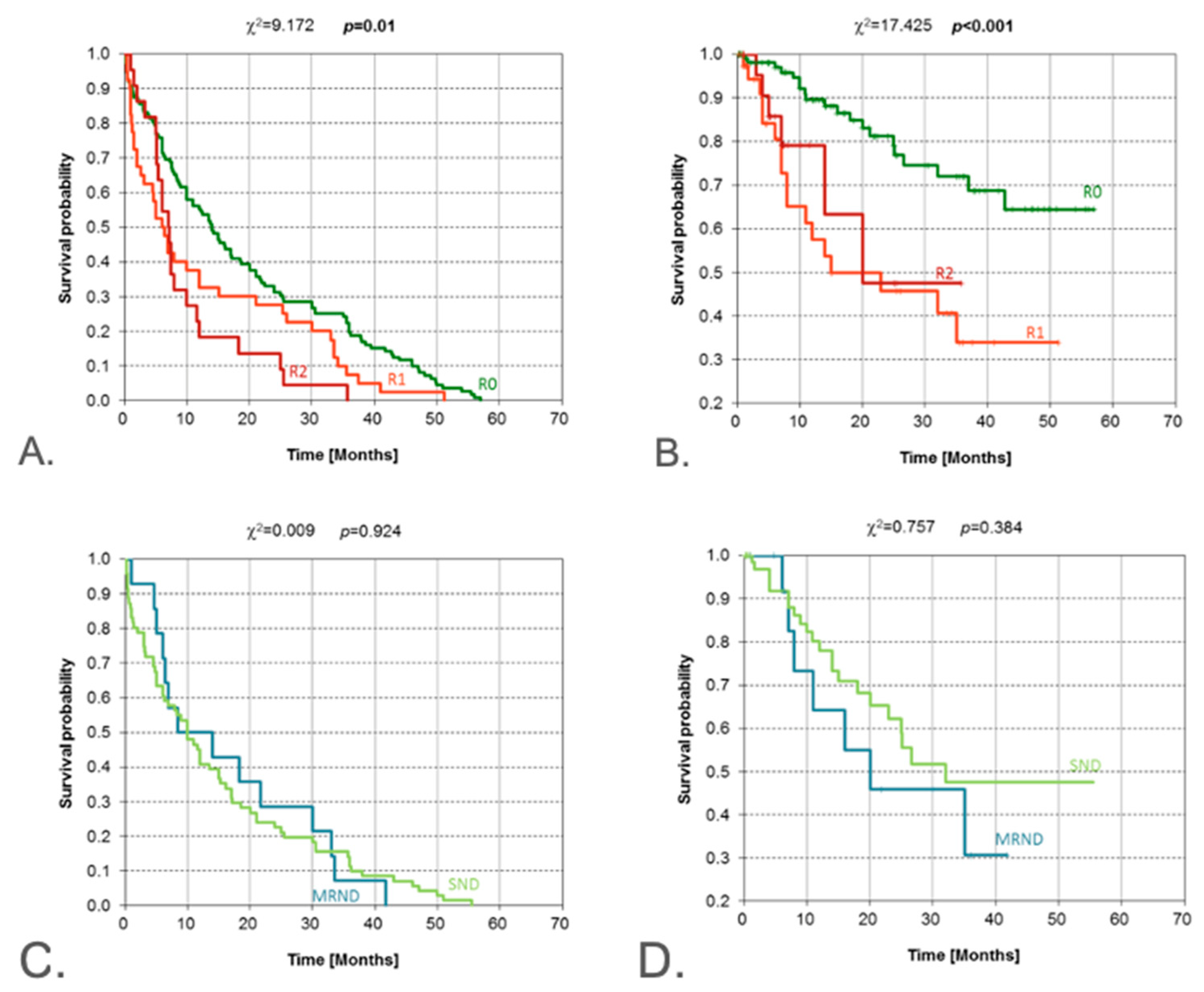

3.7. Histopathological Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Symptoms

4.2. Data from Medical Interview

4.3. Histology Findings

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bjørndal, K.; Krogdahl, A.; Therkildsen, M.H.; Overgaard, J.; Johansen, J.; Kristensen, C.A.; Homøe, P.; Sørensen, C.H.; Andersen, E.; Bundgaard, T.; et al. Salivary gland carcinoma in Denmark 1990–2005: Outcome and prognostic factors: Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Oral Oncol. 2012, 48, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, J. Salivary gland neoplasms in oral and maxillofacial regions: A 23-year retrospective study of 6982 cases in an eastern Chinese population. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 39, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengi, E.; Kara, C.; Ardi; Topuz, B. Salivary gland tumors: A 15-year experience of a universıty hospital in TurkeyNorth. Clin. Istanb. 2020, 7, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, F.; Fusco, R.; Sabbatino, F.; Fasano, M.; Ottaiano, A.; Cascella, M.; Marciano, M.L.; Pontone, M.; Salzano, G.; Maiello, M.E.; et al. Translational Insights in the Landscape of Salivary Gland Cancers: Ready for a New Era? Cancers 2024, 16, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Guidelines. Head and Neck, Version 2.2023. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1437 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Pusztaszeri, M.; Deschler, D.; Faquin, W.C. The 2021 ASCO guideline on the management of salivary gland malignancy endorses FNA biopsy and the risk stratification scheme proposed by the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2023, 131, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.L.; Ismaila, N.; Beadle, B.; Caudell, J.J.; Chau, N.; Deschler, D.; Glastonbury, C.; Kaufman, M.; Lamarre, E.; Lau, H.Y.; et al. Management of salivary gland malignancy: ASCO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1909–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, C.; Poorten, V.V.; Skalova, A.; Terhaard, C.; Maroldi, R.; van Engen, A.; Baujat, B.; Locati, L.; Jensen, A.; Smeele, L.; et al. Salivary gland cancer: ESMO–European Reference Network on Rare Adult Solid Cancers (EURACAN) Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck-Broichsitter, B.; Heiland, M.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. Salivary Gland Tumors: Limitations of International Guidelines and Status of the planned AWMF-S3-Guideline. Laryngorhinootologie 2024, 103, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarkar, A.A.; Chang, B.A. Editorial for nomograms-based prediction of overall and cancer-specific survivals for patients diagnosed with major salivary gland carcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, X.; Huang, D.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, X. Predicting cancer-specific mortality in patients with parotid gland carcinoma by competing risk nomogram. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3888–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C. Nomograms-based prediction of overall and cancer-specific survivals for patients diagnosed with major salivary gland carcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.J.; Soong, S.J.; Herrera, G.A.; Urist, M.M.; Maddox, W.A. Malignant salivary tumors--analysis of prognostic factors and survival. Head Neck Surg. 1986, 9, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Gong, Z.; Dai, Y.; Shen, W.; Zhu, H. A novel postoperative nomogram and risk classification system for individualized estimation of survival among patients with parotid gland carcinoma after surgery. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 15127–15141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, L. Prognostic models for estimating survival of salivary duct carcinoma: A population-based study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 1939–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Wen, T.; Ma, F. Clinical value of adjuvant therapy on the prognosis of ductal carcinoma of the major salivary gland: A large-scale cohort study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wei, Y.; Chai, Y.; Qi, F.; Dong, M. Prognostic Assessment and Risk Stratification in Patients with Postoperative Major Salivary Acinar Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.-S.; Huang, S.-J.; Liang, J.-F.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, J.-S. Clinical Prediction Nomograms to Assess Overall Survival and Disease-Specific Survival of Patients with Salivary Gland Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 7894523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Ma, F. Nomogram-Based Prediction of Overall and Disease-Specific Survival in Patients with Postoperative Major Salivary Gland Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat 2022, 21, 15330338221117405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Huang, Q.; Han, D.; Li, C.; Zheng, S.; Lyu, J. Competing-risks nomograms for predicting cause-specific mortality in parotid-gland carcinoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 3756–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, N.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, F.; Cao, D.; Chen, T. Characterization of parotid gland tumors: Whole-tumor histogram analysis of diffusion weighted imaging, diffusion kurtosis imaging, and intravoxel incoherent motion—A pilot study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 170, 111199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.D.; Baloch, Z.; Barkan, G.; Foschini, M.P.; Kurtycz, D.; Pusztaszeri, M.; Vielh, P.; Faquin, W.C. Second edition of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: Refining the role of salivary gland FNA. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2024, 13, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Naggar, A.K.; Chan, J.K.C.; Grandis, J.R.; Takata, T.; Slootweg, P.J. WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours, 4th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka, M.; Bartkowiak, E.; Pietruszewska, W.; Stodulski, D.; Markowski, J.; Burduk, P.; Olejniczak, I.; Piernicka-Dybich, A.; Wierzchowska, M.; Amernik, K.; et al. Rationale for Increasing Oncological Vigilance in Relation to Clinical Findings in Accessory Parotid Gland—Observations Based on 2192 Cases of the Polish Salivary Network Database. Cancers 2024, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, K.; Bartkowiak, E.; Klimza, H.; Greczka, G.; Wierzbicka, M. Review and characteristics of 585 salivary gland neoplasms from a tertiary hospital registered in the Polish National Major Salivary Gland Benign Tumors Registry over a period of 5 years: A prospective study. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2020, 74, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locati, L.D.; Ferrarotto, R.; Licitra, L.; Benazzo, M.; Preda, L.; Farina, D.; Gatta, G.; Lombardi, D.; Nicolai, P.; Poorten, V.V.; et al. Current management and future challenges in salivary glands cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1264287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, O.V.d.O.; Rêgo, T.J.R.D.; Mendes, F.H.d.O.; Dantas, T.S.; Cunha, M.D.P.S.S.; Malta, C.E.N.; Silva, P.G.d.B.; Sousa, F.B. Prognostic factors and overall survival in a 15-year followup of patients with malignant salivary gland tumors: A retrospective analysis of 193 patients. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gregoire, C. Salivary Gland Tumours. In Current Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.C.; Jethwa, A.R.; Khariwala, S.S.; Johnson, J.; Shin, J.J. Sensitivity, specificity, and posttest probability of parotid fine-needle aspiration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S.; Srinivas, T.; Hariprasad, S. Parotid gland tumors: 2-year prospective clinicopathological study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 9, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, C.; Bailey, G.; Graham, A.; Bonilla, L.M.; Sanchez, S.; Maleki, Z. Pitfalls in Salivary Gland Cytology. Acta Cytol. 2024, 68, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B.; Verillaud, B.; Jegoux, F.; Dang, N.P.; Baujat, B.; Chabrillac, E.; Vergez, S.; Fakhry, N. Surgery of major salivary gland cancers: REFCOR recommendations by the formal consensus method. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2023, 141, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantù, G. Radical Resection of Malignant Tumors of Major Salivary Glands: Is This Possible? Cancers 2024, 16, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rached, L.; Saleh, K.; Casiraghi, O.; Even, C. Salivary gland carcinoma: Towards a more personalised approach. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024, 124, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremek-Ochniak, W.; Skulimowska, J.; Płachta, I.; Szafarowski, T.; Kukwa, W. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 407 salivary glands neoplasms in surgically treated patients in 2010–2020. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2022, 76, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, H.; Kruger, E.; Ahmadvand, S.; Mohammadi, Y.; Khademi, B.; Ghaderi, A. Epidemiological Profile of Salivary Gland Tumors in Southern Iranian Population: A Retrospective Study of 405 Cases. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2023, 2023, 8844535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckenzie, J.; Lockyer, J.; Singh, T.; Nguyen, E. Salivary gland tumours: An epidemiological review of non-neoplastic and neoplastic pathology. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 61, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, C.; Wagner, S.; Kluβmann, J.P.; Pons-Kühnemann, J.; Arens, C.; Langer, C.; Wittekindt, C. Salivary gland carcinomas—Monocentric experience on subtypes and their incidences over 42 years. Laryngorhinootologie 2022, 102, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, J.K.; Mace, J.C.; Clayburgh, D. Contemporary treatment patterns and outcomes of salivary gland carcinoma: A National Cancer Database review. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2019, 276, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, E.; Van Lierde, C.; Zlate, A.; Jensen, A.; Gatta, G.; Didonè, F.; Licitra, L.F.; Grégoire, V.; Vander Poorten, V.; Locati, L.D. Salivary gland cancers in elderly patients: Challenges and therapeutic strategies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1032471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupancic, M.; Näsman, A.; Berglund, A.; Dalianis, T.; Friesland, S. Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma (AdCC): A Clinical Survey of a Large Patient Cohort. Cancers 2023, 15, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Grose, E.M.; Philteos, J.; Levin, M.; de Almeida, J.; Goldstein, D. Clinicopathological Predictors of Survival for Parotid Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.; McGill, M.; Mimica, X.; Eagan, A.; Hay, A.; Wu, J.; Cohen, M.A.; Patel, S.G.; Ganly, I. Evaluation of Surgical Margin Status in Patients with Salivary Gland Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 148, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinicopathological Features | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21–97 (mean 63.38) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 125 (55.6%) |

| Women | 104 (45.4%) |

| Clinical symptoms of malignancy | 79—yes |

| 96—no | |

| No data for 54 subjects | |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 1–12 (mean duration 3.87 months) |

| Radiological signs of malignancy | 95—yes |

| 79—no | |

| No data for 55 subjects | |

| Preoperative facial nerve palsy | Yes—22 |

| No—141 | |

| No data for 65 subjects | |

| Postoperative facial nerve palsy | 69—yes |

| 24—yes, partial | |

| 111—no | |

| No data for 25 subjects | |

| Duration of paresis in nerve VII | 76—no nerve paresis |

| 50—permanent paresis | |

| Transient paresis: | |

| >7 days–1 month—8 subjects | |

| 1–3 months—6 subjects | |

| 3–6 months—6 subjects | |

| 6–12 months—5 subjects | |

| No data for 78 subjects | |

| Tumor size | No data for 7 subjects |

| <2 cm | 57 |

| 2–4 cm | 106 |

| >4 cm | 59 |

| Place of residence | No data for 2 subjects |

| Rural area | 71 (31%) |

| Town <100,000 inhabitants | 60 (26%) |

| Town/city, population 100,000–500,000 inhabitants | 58 (25%) |

| City, population >500,000 inhabitants | 38 (16%) |

| Cigarette smoking | 49-yes |

| 79-no | |

| No data for 101 subjects | |

| Alcohol consumption | 5-yes |

| 121-no | |

| No data for 103 subjects | |

| Exposure to chemicals | 11-yes |

| 114-no | |

| No data for 104 subjects | |

| Exposure to radiation | 29-yes, |

| 96-no | |

| No data for 104 subjects | |

| Neck dissection | |

| SND | 121 |

| RND | 5 |

| MRND | 24 |

| No nodal surgery performed | 79 |

| Resection | |

| R0 | 168 |

| R1 | 32 |

| R2 | 29 |

| Complementary treatment: | |

| radiotherapy | 139 |

| Chemotherapy | 6 |

| No adjuvant therapy | 84 |

| pT-stage | |

| T1 | 74 |

| T2 | 75 |

| T3 | 39 |

| T4a | 37 |

| T4b | 4 |

| pN-stage | |

| N0 | 149 |

| N1 | 47 |

| N2a | 5 |

| N2b | 18 |

| N3a | 3 |

| N3b | 7 |

| pM-stage | |

| M0 | 229 |

| M1 | 0 |

| Clinical stage | |

| I | 74 |

| II | 75 |

| III | 37 |

| IVa | 23 |

| IVb | 12 |

| No. | Histopathological Diagnosis | No. of Cases | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 30 | 13 |

| 2 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 including 24 (80%) primary salivary SCC and 6 metastatic SCC (20%) to intraparotid nodes | 13 |

| 3 | Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 20 | 8 |

| 4 | Acinic cell carcinoma | 20 | 8 |

| 5 | Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 17 | 7.5 |

| 6 | Salivary duct carcinoma | 15 | 6.5 |

| 7 | Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | 11 | 4.8 |

| 8 | Myoepithelial carcinoma | 8 | 3.4 |

| 9 | Adenocarcinoma, NOS | 7 | 3.0 |

| 10 | Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 6 | 2.6 |

| 11 | Polymorphous adenocarcinoma | 4 | 1.7 |

| 12 | Basal cell adenocarcinoma | 6 | 2 |

| 13 | Intraductal carcinoma | 1 | 0.004 |

| 14 | Adenocarcinoma cribriform | 2 | 0.008 |

| 15 | Secretory carcinoma | 2 | 0.008 |

| 16 | Carcinosarcoma | 3 | 1.3 |

| 17 | Undifferentiated carcinoma | 4 | 1.7 |

| 18 | Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | Metastasis of neuroendocrine tumor | 1 | 0.004 |

| 20 | Lymphoepithelial carcinoma | 2 | 0.008 |

| 21 | Oncocytic carcinoma | 3 | 1.3 |

| 22 | Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MALT) | 24 | 10 |

| 23 | Metastasis of melanoma | 1 | 0.004 |

| 24 | other lymphomas | 12 | 5.2 |

| Total | 229 | 100 |

| Location (ESGS) | Number of Patients (n) | % of Patients |

|---|---|---|

| I | 11 | 4.8 |

| II | 40 | 17.5 |

| I_II | 45 | 19.7 |

| III | 9 | 3.9 |

| II_III | 23 | 10.0 |

| I_II_III | 6 | 2.6 |

| I_II_III_IV | 21 | 9.2 |

| IV | 1 | 0.4 |

| I_IV | 6 | 2.6 |

| V | 5 | 2.2 |

| II_III_IV | 4 | 1.7 |

| III_IV_VI | 10 | 4.4 |

| I_II_V | 5 | 2.2 |

| VI | 3 | 1.3 |

| I_II_IV | 1 | 0.4 |

| I_V | 2 | 0.9 |

| I_II_III_IV_V | 4 | 1.7 |

| I_II_III_IV_VI | 2 | 0.9 |

| III_VI | 2 | 0.9 |

| III_IV | 2 | 0.9 |

| I_II_III_IV_V_VI | 1 | 0.4 |

| II_III_VI | 1 | 0.4 |

| Submandibular | 25 | 10.9 |

| Total | 229 | 100.0 |

| Predictor | Levels (Summary) | Statistical Test | DFS p-Value | OS p-Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | Rural; small towns; cities 100–500 k; cities >500 k | Log-rank/χ2 | <0.001 | 0.009 | Better outcomes in large cities |

| Exposure: prior radiation | Yes vs. No | Log-rank | 0.004 | - | Significant for DFS; OS not reported as significant |

| Tumor size (diameter) | Ordinal increase | Log-rank/χ2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | Monotonic worsening with larger size |

| Clinical signs of malignancy | Present vs. Absent | Log-rank | 0.001 | 0.002 | Early months especially impacted |

| Pathological T (pT) | T1–T4 | χ2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | Clear separation of curves |

| Pathological N (pN) | N0–N3 | χ2 | 0.001 | 0.032 | Nodal involvement worsens outcomes |

| Clinical stage (AJCC) | I–IV | χ2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | Progressive decline by stage |

| Resection margins | R0 vs. R1/R2 (positive) | χ2 | 0.010 | <0.001 | R0 strongly favorable for OS |

| Gender | Female vs. Male | Log-rank | 0.051 | - | Borderline/not significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markowski, J.; Pietruszewska, W.; Bartkowiak, E.; Mikaszewski, B.; Stodulski, D.; Burduk, P.; Radomska, K.; Olejniczak, I.; Piernicka-Dybich, A.; Wierzchowska, M.; et al. Prognostic Factors in Salivary Gland Malignancies: A Multicenter Study of 229 Patients from the Polish Salivary Network Database. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238527

Markowski J, Pietruszewska W, Bartkowiak E, Mikaszewski B, Stodulski D, Burduk P, Radomska K, Olejniczak I, Piernicka-Dybich A, Wierzchowska M, et al. Prognostic Factors in Salivary Gland Malignancies: A Multicenter Study of 229 Patients from the Polish Salivary Network Database. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238527

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkowski, Jarosław, Wioletta Pietruszewska, Ewelina Bartkowiak, Bogusław Mikaszewski, Dominik Stodulski, Paweł Burduk, Katarzyna Radomska, Izabela Olejniczak, Aleksandra Piernicka-Dybich, Małgorzata Wierzchowska, and et al. 2025. "Prognostic Factors in Salivary Gland Malignancies: A Multicenter Study of 229 Patients from the Polish Salivary Network Database" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238527

APA StyleMarkowski, J., Pietruszewska, W., Bartkowiak, E., Mikaszewski, B., Stodulski, D., Burduk, P., Radomska, K., Olejniczak, I., Piernicka-Dybich, A., Wierzchowska, M., Chańko, A., Majszyk, D., Bruzgielewicz, A., Gazińska, P., & Wierzbicka, M. (2025). Prognostic Factors in Salivary Gland Malignancies: A Multicenter Study of 229 Patients from the Polish Salivary Network Database. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238527