Liver Fibrosis as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Severe Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Baseline Characteristics

2.4. Laboratory Measurements

2.5. Carotid Intima Media Thickness

2.6. Pulse Wave Velocity

2.7. Fibrosis-4 Index

2.8. Statistical Analyses

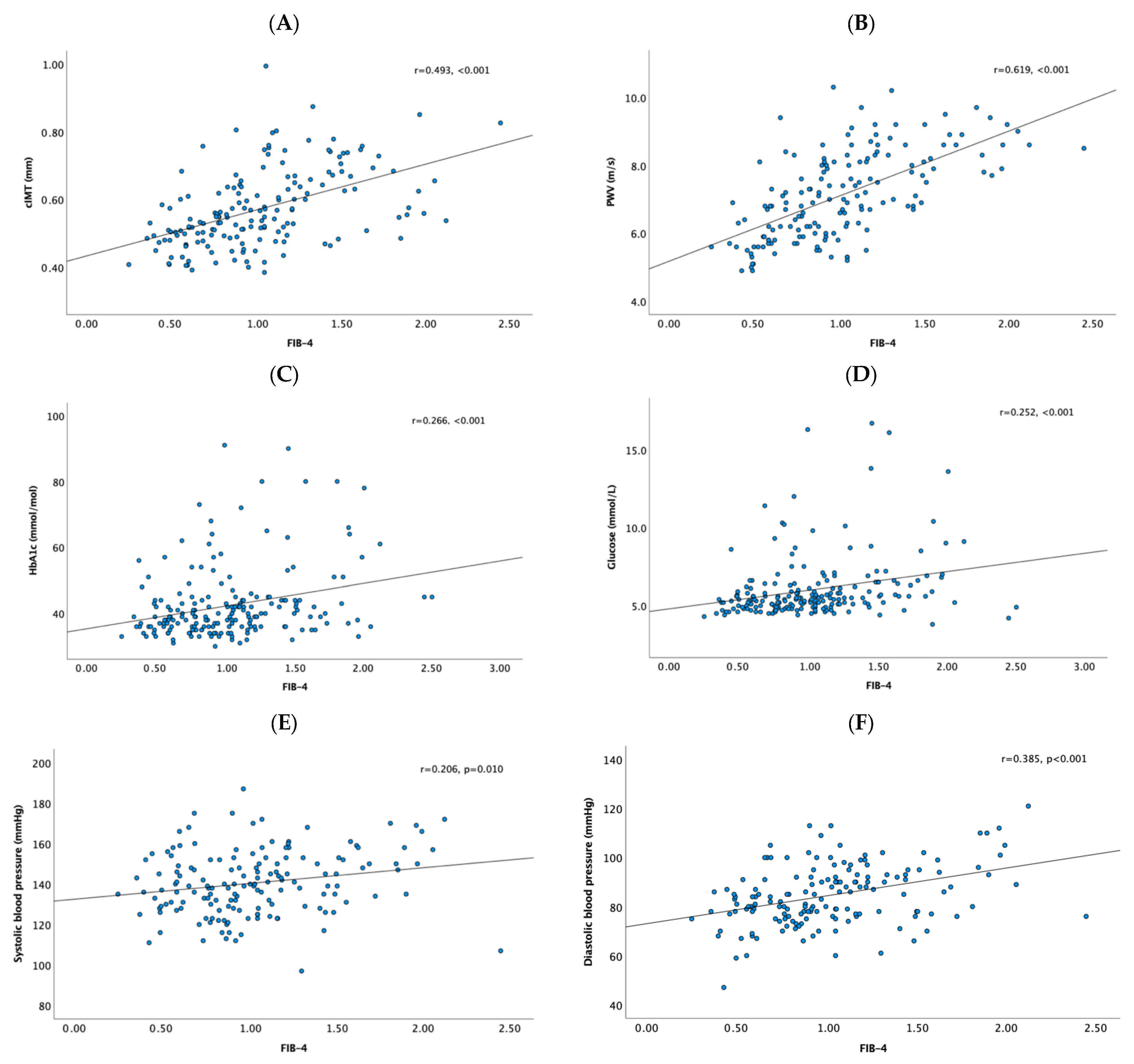

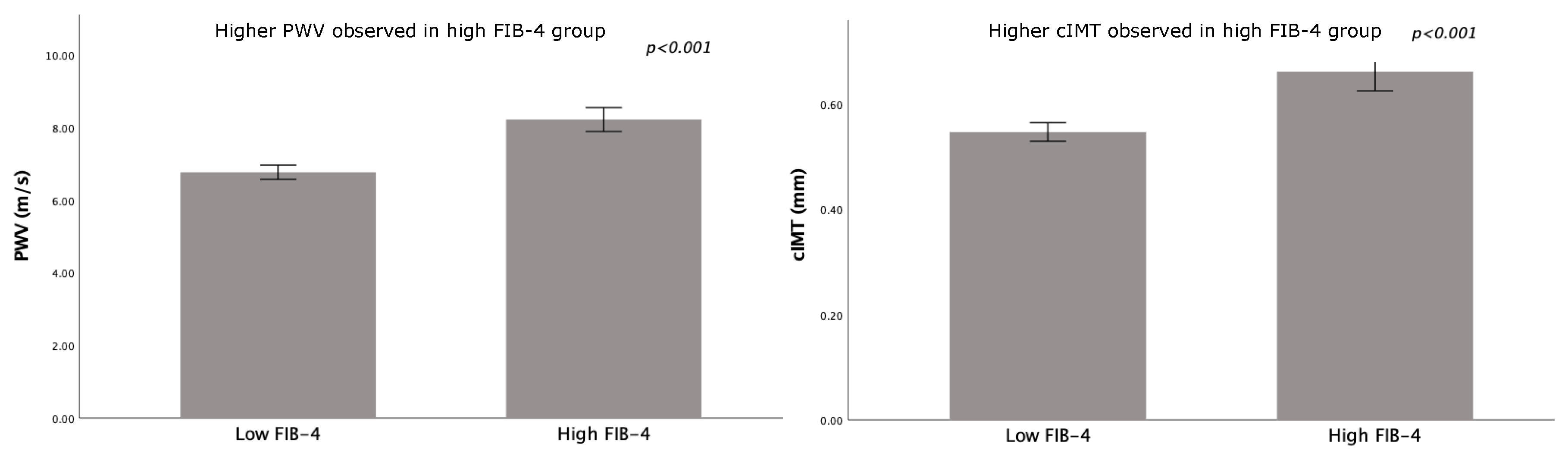

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| cIMT | Carotid intima media thickness |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 index |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| IFSO | International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NIT | Non-invasive test |

| PWV | Pulse wave velocity |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| WHO | World health organization |

Appendix A

| Patients (N = 200) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Sex (f/m) [n, %] | 148 (74)/52 (26) |

| Age (years) | 41 ± 12 |

| Body weight (kg) | 125 ± 21 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 42.7 ± 5.2 |

| Ethnicity Caucasian [n, %] | 145 (73.2) |

| African [n, %] | 20 (10.1) |

| Latin-American [n, %] | 6 (3.0) |

| Indian [n, %] | 8 (4.0) |

| Asian [n, %] | 1 (0.5) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Hematocrit (L/L) | 0.43 ± 0.04 |

| Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | 8.7 ± 0.81 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 140 ± 16 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 85 ± 12 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2 ± 1.1 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.1 ± 0.96 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.29 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.7 (1.2–2.7) |

| Apolipoprotein B (g/L) | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 6.1 ± 2.4 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 6 (3.0–10) |

| Leukocytes (109/L) | 8.7 ± 2.4 |

| Carotid Intima Media thickness (mm) | 0.57 ± 0.11 |

| Medication | |

| Statins [n, %] | 31 (15.5) |

| Antihypertensives [n, %] | 65 (32.5) |

| Antidiabetics [n, %] | 35 (17.5) |

| Medical history | |

| Diabetes [n, %] | 43 (21.5) |

| Hypertension [n, %] | 69 (34.5) |

| Hypercholesterolemia [n, %] | 58 (29) |

| CVA or TIA [n, %] | 5 (2.5) |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 (3) |

| Fibrosis markers | |

| Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) | |

| Total population | 1.02 ± 0.44 |

| FIB-4 score <1.3 [n, %] | 155 (77.5) |

| FIB-4 score ≥1.3 [n, %] | 45 (22.5) |

| Subgroup | FIB-4 Category | cIMT (mm) | N | p-Value cIMT | PWV (m/s) | N | p-Value PWV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertensive | Low FIB-4 | 0.59 ± 0.11 | 66 | <0.001 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 64 | <0.001 |

| High FIB-4 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 28 | 8.4 ± 0.9 | 25 | |||

| Diabetic | Low FIB-4 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 21 | 0.303 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 20 | 0.079 |

| High FIB-4 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | 10 | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 8 |

| Variable | B | Std. Error | Beta | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.566 | 0.660 | - | 0.394 | - |

| Age (years) | 0.021 | 0.004 | 0.501 | <0.001 | 2.02 |

| cIMT (mm) | 0.832 | 0.416 | 0.208 | 0.049 | 2.04 |

| Sex (female/male) | −0.130 | 0.100 | −0.126 | 0.198 | 1.77 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.083 | 0.373 | 1.62 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.018 | 0.831 | 1.35 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.105 | 0.215 | 1.32 |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 0.017 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.651 | 1.28 |

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 0.029 | 0.172 | 0.017 | 0.865 | 1.80 |

| Triglycerides (g/L) | 0.008 | 0.048 | 0.014 | 0.877 | 1.63 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | −0.002 | 0.004 | −0.036 | 0.695 | 1.60 |

| CRP (mg/L) | −0.007 | 0.005 | −0.118 | 0.162 | 1.30 |

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.266 | 1.089–1.471 | 0.002 |

| cIMT (per 0.1 mm) | 1.947 | 0.871–4.354 | 0.107 |

| Sex (female/male) | 0.339 | 0.040–2.881 | 0.363 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.064 | 0.907–1.247 | 0.446 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 1.011 | 0.960–1.065 | 0.692 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 1.100 | 1.000–1.210 | 0.049 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.597 | 0.614–4.150 | 0.336 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.902 | 0.116–31.198 | 0.758 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 1.404 | 0.482–4.089 | 0.522 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.990 | 0.909–1.078 | 0.838 |

| Predictor | B | Standard Error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.431 | 0.088 | <0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 0.054 | 0.024 | 0.026 |

| Age spline 1 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.839 |

| Age spline 2 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.066 |

| Age spline 3 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.166 |

| Age spline 4 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.264 |

References

- Friedrich, M.J. Global Obesity Epidemic Worsening. JAMA 2017, 318, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, K.; Azhari, H.; Charette, J.H.; Underwood, F.E.; King, J.A.; Afshar, E.E.; Swain, M.G.; Congly, S.E.; Kaplan, G.G.; Shaheen, A.A. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Fact Sheet Obesity and Overweight; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Afshin, A.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Reitsma, M.B.; Sur, P.; Estep, K.; Lee, A.; Marczak, L.; Mokdad, A.H.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Naghavi, M.; et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.; Card, T.R.; Delahooke, T.; Aithal, G.P.; Guha, I.N. Obesity Is the Most Common Risk Factor for Chronic Liver Disease: Results From a Risk Stratification Pathway Using Transient Elastography. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1744–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francque, S.M.A.; Dirinck, E. NAFLD prevalence and severity in overweight and obese populations. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Horn, P.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Ratziu, V.; Bugianesi, E.; Francque, S.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Valenti, L.; Roden, M.; Schick, F.; et al. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 492–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.B. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: The hepatic consequence of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.; Ekstedt, M.; Wong, G.L.; Hagström, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theel, W.; Boxma-de Klerk, B.M.; Dirksmeier-Harinck, F.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; Kanhai, D.A.; Apers, J.; van Dalen, B.M.; de Knegt, R.J.; Holleboom, A.G.; Tushuizen, M.E.; et al. Evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in severe obesity using noninvasive tests and imaging techniques. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divella, R.; Mazzocca, A.; Daniele, A.; Sabbà, C.; Paradiso, A. Obesity, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Adipocytokines Network in Promotion of Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaben, A.L.; Scherer, P.E. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus 2022, 14, e22711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijhuis, J.; Rensen, S.S.; Slaats, Y.; van Dielen, F.M.; Buurman, W.A.; Greve, J.W. Neutrophil activation in morbid obesity, chronic activation of acute inflammation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009, 17, 2014–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaszczak, A.M.; Jalilvand, A.; Hsueh, W.A. Adipocytes, innate immunity and obesity: A mini-review. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 650768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizi, G.; Della Guardia, L.; Maurizi, A.; Poloni, A. Adipocytes properties and crosstalk with immune system in obesity-related inflammation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, S.; Rhodes, F.; Srivastava, A.; Trembling, P.M.; Rosenberg, W.M. Inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Grau, A.; Gabriel-Medina, P.; Rodriguez-Algarra, F.; Villena, Y.; Lopez-Martínez, R.; Augustín, S.; Pons, M.; Cruz, L.M.; Rando-Segura, A.; Enfedaque, B.; et al. Assessing Liver Fibrosis Using the FIB4 Index in the Community Setting. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, J.; Verhulst, S.; Mannaerts, I.; Reynaert, H.; van Grunsven, L.A. Prospects in non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis: Liquid biopsy as the future gold standard? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mil, S.R.; Vijgen, G.; van Huisstede, A.; Klop, B.; van de Geijn, G.M.; Birnie, E.; Braunstahl, G.J.; Mannaerts, G.H.H.; Biter, L.U.; Castro Cabezas, M. Discrepancies Between BMI and Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3484–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mil, S.R.; Biter, L.U.; van de Geijn, G.M.; Birnie, E.; Dunkelgrun, M.; JNM, I.J.; van der Meulen, N.; Mannaerts, G.H.H.; Castro Cabezas, M. Contribution of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus to Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Subjects with Morbid Obesity. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 2509–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, M.; van Mil, S.R.; Al-Ghanam, I.; Biter, L.U.; Dunkelgrun, M.; Castro Cabezas, M. Structural and functional vascular improvement 1 year after bariatric surgery: A prospective cohort study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissas, J. IFSO Guidelines for Safety, Quality, and Excellence in Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2008, 18, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, M.A.; Klop, B.; Alipour, A.; van de Geijn, G.J.; Prinzen, L.; Liem, A.H.; Valdivielso, P.; Rioja Villodres, J.; Ramírez-Bollero, J.; Castro Cabezas, M. In vivo evidence for chylomicrons as mediators of postprandial inflammation. Atherosclerosis 2015, 243, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, S.A.; Klop, B.; Alipour, A.; Martinez-Hervas, S.; Westzaan, A.; van de Geijn, G.J.; Janssen, H.W.; Njo, T.; Birnie, E.; van Mechelen, R.; et al. Erythrocyte-associated apolipoprotein B and its relationship with clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 42, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Mil, S.R.; Biter, L.U.; van de Geijn, G.J.M.; Birnie, E.; Dunkelgrun, M.; Ijzermans, J.N.M.; van der Meulen, N.; Mannaerts, G.H.H.; Castro Cabezas, M. The effect of sex and menopause on carotid intima-media thickness and pulse wave velocity in morbid obesity. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 49, e13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilek, J.; Fukushima, T. Oscillometric blood pressure measurement: The methodology, some observations, and suggestions. Biomed. Instrum. Technol. 2005, 39, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, T.; Lv, N.; Dang, A.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, W. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and prognosis in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens. Res. 2021, 44, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davyduke, T.; Tandon, P.; Al-Karaghouli, M.; Abraldes, J.G.; Ma, M.M. Impact of Implementing a “FIB-4 First” Strategy on a Pathway for Patients With NAFLD Referred From Primary Care. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosen, S.H.; Kostev, K.; Keitel, V.; Tacke, F.; Roderburg, C.; Luedde, T. An elevated FIB-4 score predicts liver cancer development: A longitudinal analysis from 29,999 patients with NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis—2021 update. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 659–689. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, D.; Ye, X. Bidirectional Association between Hypertension and NAFLD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 2022, 8463640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. Association between hypertension and the prevalence of liver steatosis and fibrosis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, J.H. Association between Estimated Pulse Wave Velocity and Incident Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Korean Adults. Pulse 2024, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, J.; Sun, W.; Xu, B.; Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, X.; et al. Advanced fibrosis associates with atherosclerosis in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabahbeh, R.H.; Obeidat, A.N.; Jaber, D.S.; AlKhaldi, M.M.; Ghanem, L.K.; Tubasi, A.A.; Obeidat, Z.N.; Alhawari, H.H. Screening for the Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Among Patients With Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes: A Comparison of Three Screening Systems. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 2025, 6676114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, V.; Fabre, O.; Legrand, R.; Bailly, S.; Costentin, C. FIB-4: A screening tool for advanced liver fibrosis in a cohort of subjects participating in a primary care weight-loss program. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0333490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Emberson, J.; Holland, L.E.; Reith, C.; Bhala, N.; Peto, R.; Barnes, E.H.; Keech, A.; Simes, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010, 376, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Barter, P.J.; Chapman, M.J.; Erbel, R.M.; Libby, P.; Raichlen, J.S.; Uno, K.; Borgman, M.; Wolski, K.; et al. Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, S.O.; Budoff, M. Effect of statins on atherosclerotic plaque. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 29, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulson, K.E.; Zhu, S.N.; Chen, M.; Nurmohamed, S.; Jongstra-Bilen, J.; Cybulsky, M.I. Resident intimal dendritic cells accumulate lipid and contribute to the initiation of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Brussel, I.; Ammi, R.; Rombouts, M.; Cools, N.; Vercauteren, S.R.; De Roover, D.; Hendriks, J.M.H.; Lauwers, P.; Van Schil, P.E.; Schrijvers, D.M. Fluorescent activated cell sorting: An effective approach to study dendritic cell subsets in human atherosclerotic plaques. J. Immunol. Methods 2015, 417, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, M.; Van Eck, M. High-density lipoproteins and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atheroscler. Plus 2023, 53, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiki, N.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Mantzoros, C.S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia: An update. Metabolism 2016, 65, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.G.; Mukamal, K.; Tapper, E.; Robson, S.C.; Tsugawa, Y. Low LDL-C and high HDL-C levels are associated with elevated serum transaminases amongst adults in the United States: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Sun, X. Cholesterol Metabolism: A Double-Edged Sword in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 762828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi-Cervera, L.A.; Montalvo, G.I.; Icaza-Chávez, M.E.; Torres-Romero, J.; Arana-Argáez, V.; Ramírez-Camacho, M.; Lara-Riegos, J. Clinical relevance of lipid panel and aminotransferases in the context of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis as measured by transient elastography (FibroScan®). J. Med. Biochem. 2021, 40, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J.B.; Simon, T.G.; Kaplan, A.; Osganian, S.; Masia, R.; Corey, K.E. Advanced fibrosis is associated with incident cardiovascular disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low FIB-4 N = 155 | High FIB-4 N = 45 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 38 ± 11 | 53 ± 5.2 | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) female | 123 (79) | 25 (56) | 0.001 * |

| Body weight (kg) | 124 ± 19 | 126 ± 28 | 0.691 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 42.5 ± 4.4 | 43.3 ± 7.2 | 0.458 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 129 ± 12 | 131 ± 16 | 0.341 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 27 (17.4) | 16 (35.6) | 0.013 † |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| FIB-4 | 0.83 ± 0.26 | 1.67 ± 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit (L/L) | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.524 |

| Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 0.194 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 139 ± 15 | 146 ± 16 | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 83 ± 12 | 91 ± 13 | 0.002 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 0.197 |

| Triglycerides (g/L) | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 0.359 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.29 | 1.3 ± 0.31 | 0.278 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.1 ± 0.92 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 0.221 |

| Apolipoprotein B (g/L) | 1.1 ± 0.29 | 1.2 ± 0.33 | 0.069 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 41 ± 9.5 | 48 ± 14 | 0.002 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 7.0 ± 2.9 | 0.006 |

| Insulin (µIU/mL) | 23 (17–44) | 30 (18–47) | 0.998 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 6 (3–10) | 5 (3–9) | 0.199 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 65 ± 14 | 71 ± 16 | 0.038 |

| Homocystein (µmol/L) | 11.5 ± 4.1 | 14.0 ± 9.6 | 0.167 |

| TSH (mU/l) | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | 2.0 (1.5–2.6) | 0.934 |

| Medication | |||

| Statins, n (%) | 16 (10.3%) | 15 (33.3%) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensives, n (%) | 43 (27.7%) | 22 (48.9%) | 0.011 |

| Antidiabetics, n (%) | 22 (14.2%) | 13 (28.9%) | 0.027 |

| Medication | Low FIB-4 (%) | High FIB-4 (%) | X2 | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statins | 10.3 | 33.3 | 14.099 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensives | 27.7 | 48.9 | 7.109 | 0.011 |

| Antidiabetics | 14.2 | 28.9 | 5.217 | 0.027 |

| Leukocyte Activation Marker | Low FIB-4 | High FIB-4 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD35 on monocytes (au) | 7.3 ± 3.6 | 7.1 ± 3.0 | 0.680 |

| CD35 on granulocytes (au) | 10.7 ± 5.0 | 10.5 ± 6.5 | 0.815 |

| CD11b on monocytes (au) | 34.6 ± 10.2 | 31.6 ± 7.8 | 0.070 |

| CD11b on granulocytes (au) | 47.5 ± 15 | 44.8 ± 16 | 0.303 |

| CD66b on granulocytes (au) | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 0.070 |

| Standardized Coefficients Beta | VIF | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | - | 0.016 | - |

| Age (years) | 0.438 | 1.782 | <0.001 |

| CD66b on granulocytes (au) | 0.163 | 1.356 | 0.033 |

| CD11b on monocytes (au) | 0.061 | 1.427 | 0.429 |

| FIB-4 | 0.143 | 1.443 | 0.069 |

| Sex (m/f) | −0.229 | 1.339 | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.063 | 1.241 | 0.387 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.039 | 2.267 | 0.691 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −0.033 | 2.576 | 0.749 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saidi, A.N.; Theel, W.B.; de Jong, V.D.; van Mil, S.R.; van der Lely, A.-J.; Grobbee, D.E.; Apers, J.; Beek, E.v.d.Z.-v.; Castro Cabezas, M. Liver Fibrosis as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Severe Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238532

Saidi AN, Theel WB, de Jong VD, van Mil SR, van der Lely A-J, Grobbee DE, Apers J, Beek EvdZ-v, Castro Cabezas M. Liver Fibrosis as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Severe Obesity. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238532

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaidi, Alina N., Willy B. Theel, Vivian D. de Jong, Stefanie R. van Mil, Aart-Jan van der Lely, Diederick E. Grobbee, Jan Apers, Ellen van der Zwan-van Beek, and Manuel Castro Cabezas. 2025. "Liver Fibrosis as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Severe Obesity" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238532

APA StyleSaidi, A. N., Theel, W. B., de Jong, V. D., van Mil, S. R., van der Lely, A.-J., Grobbee, D. E., Apers, J., Beek, E. v. d. Z.-v., & Castro Cabezas, M. (2025). Liver Fibrosis as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Severe Obesity. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238532