Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of FGFR3, TP53 Mutation and Urinary Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma in Pakistani Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Patient Recruitment, Clinical Evaluation, and Clinicopathological Data Collection

2.3. Patient Selection Criteria

2.4. Sample Collection and Processing

2.4.1. Urine and Bladder Tissue Samples

2.4.2. Cytopathological Examination

2.4.3. Histopathological Examination of Tissue Specimens

2.4.4. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining Protocol

2.4.5. Immunohistochemistry Using FGFR3 and p53 Antibodies

2.5. Genotyping of FGFR3 and TP53

2.5.1. Genomic DNA Extraction

2.5.2. Primer Design and Target Regions

2.5.3. PCR Amplification of FGFR3 and TP53

2.5.4. Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization

2.5.5. DNA Sequencing

2.5.6. Custom PCR and Sanger Sequencing

2.5.7. Mutational Analysis

2.6. Xpert Bladder Cancer Monitor (BCM) Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Study Patients

3.2. Cystoscopic Analysis of Patients

3.3. Immunohistochemical Scoring for FGFR3 and p53

3.4. Mutation Analysis of FGFR3 and TP53

3.5. Correlation of FGFR3 Mutations with Immunohistochemical Protein Expression

3.6. Association of TP53 Mutation with Immunohistochemical Protein Expression

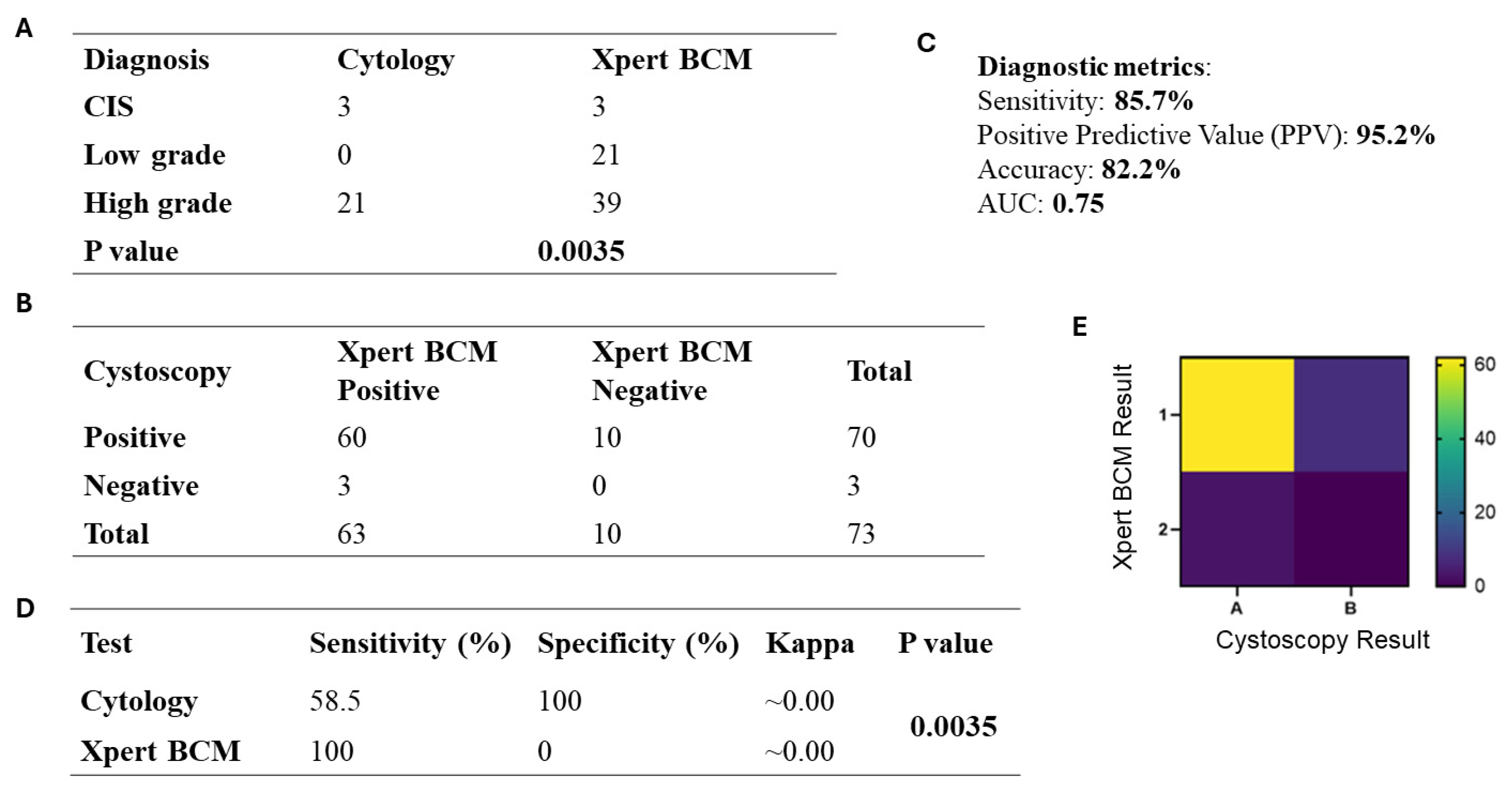

3.7. Xpert Bladder Cancer Monitor (BCM) Analysis

3.8. Comparison of Xpert BCM with Cystoscopy in UC Patients

3.9. Comparison of Cytology with Xpert BCM in UC Patients

4. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FGFR3 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 |

| TP53 | Tumour protein p53 |

| BC | Bladder cancer |

| UC | Urothelial carcinoma |

| NMIBC | Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| MIBC | Muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| BCM | Bladder cancer monitor |

| US FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| TURBT | Transurethral resection of bladder tumour |

| FFPE | Formalin fixed paraffin embedded |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| µm | Micron metre |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| CIS | Carcinoma in situ |

| TNM | Tumour node metastasis |

| HVGS | Human Genome Variation Society |

| MAPK | Mitogen activated protein kinase |

| miRNAs | Micro ribonucleic acids |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| SPSS | Statistical package for social sciences |

References

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of bladder cancer. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, A.; Pervez, S.; Khadim, M.T.; Sohaib, M.; Uddin, H.; Badar, F.; Masood, A.I.; Khattak, Z.I.; Naz, S.; Rahat, T. National cancer registry of Pakistan: First comprehensive report of cancer statistics 2015-2019. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2023, 33, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Z.; He, Z.; Zhuo, H.; Huang, Y.; Kong, J. Smoking and bladder cancer: Insights into pathogenesis and public health implications from a bibliometric analysis (1999–2023). Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2025, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamri, M.; Walmsley, S.J.; Brown, C.; Brandt, K.; Konorev, D.; Day, A.; Wu, C.-F.; Wu, M.T.; Turesky, R.J. DNA damage and oxidative stress of tobacco smoke condensate in human bladder epithelial cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1863–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossanen, M.; Nassar, A.H.; Stokes, S.M.; Martinez-Chanza, N.; Kumar, V.; Nuzzo, P.V.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Garber, J.E.; Curran, C.; Freeman, D. Incidence of germline variants in familial bladder cancer and among patients with cancer predisposition syndromes. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2022, 20, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Mahal, V.; Verma, G.; Bhatia, S.; Das, B.R. Molecular investigation of FGFR3 gene mutation and its correlation with clinicopathological findings in Indian bladder cancer patients. Cancer Rep. 2018, 1, e1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, C.M.; Napolitano, F.; Esposito, D.; Servetto, A.; Belli, S.; Santaniello, A.; Scagliarini, S.; Crocetto, F.; Bianco, R.; Formisano, L. Role of FGFR3 in bladder cancer: Treatment landscape and future challenges. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 115, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, K.; Necchi, A.; Burn, T.; Gjoerup, O.; Greenstein, R.; Krook, M.; López, J.; Montesion, M.; Nimeiri, H.; Parikh, A. Pan-tumor landscape of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-4 genomic alterations. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, F.; Li, K.; Li, S.; Zhao, C.; Fan, C.; Wang, J. Significance of TP53 mutation in bladder cancer disease progression and drug selection. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lv, D.; Cai, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. A TP53-associated immune prognostic signature for the prediction of overall survival and therapeutic responses in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 590618. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhuang, G.; Sun, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Di, W. TP53 mutation-mediated genomic instability induces the evolution of chemoresistance and recurrence in epithelial ovarian cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 2017, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, T.; Su, W.; Dou, Z.; Zhao, D.; Jin, X.; Lei, H.; Wang, J.; Xie, X.; Cheng, B. Mutant p53 in cancer: From molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Park, S.H.; Garcia-Donas, J.; Huddart, R.; Burgess, E.; Fleming, M.; Rezazadeh, A.; Mellado, B.; Varlamov, S. Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krook, M.A.; Reeser, J.W.; Ernst, G.; Barker, H.; Wilberding, M.; Li, G.; Chen, H.-Z.; Roychowdhury, S. Fibroblast growth factor receptors in cancer: Genetic alterations, diagnostics, therapeutic targets and mechanisms of resistance. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.J.; Hsu, R. Treatment approaches for FGFR-altered urothelial carcinoma: Targeted therapies and immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1258388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.-L.; Su, F.; Yang, J.-R.; Xiao, R.-W.; Wu, R.-Y.; Cao, M.-Y.; Ling, X.-L.; Zhang, T. TP53 to mediate immune escape in tumor microenvironment: An overview of the research progress. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Santos, G.S.; Zhan, Y.; Oliveira, M.M.; Rezaei, S.; Singh, M.; Peuget, S.; Westerberg, L.S.; Johnsen, J.I.; Selivanova, G. Mutant p53 gain of function mediates cancer immune escape that is counteracted by APR-246. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 2060–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting p53 pathways: Mechanisms, structures and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, H. FDA grants breakthrough device designation to urine test for bladder cancer detection. Urol. Times 2025, 53, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kavcic, N.; Peric, I.; Zagorac, A.; Kokalj Vokac, N. Clinical Evaluation of Two Non-invasive Genetic Tests for Detection and Monitoring of Urothelial Carcinoma: Validation of UroVysion and xpert bladder Cancer detection test. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 839598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Higuchi, R.; Satya, M.; McCann, L.; Sin, M.L.; Bridge, J.A.; Wei, H.; Zhang, J.; Wong, E.; Hiar, A. Development of a 90-minute integrated noninvasive urinary assay for bladder cancer detection. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valenberg, F.J.P.; Hiar, A.M.; Wallace, E.; Bridge, J.A.; Mayne, D.J.; Beqaj, S.; Sexton, W.J.; Lotan, Y.; Weizer, A.Z.; Jansz, G.K. Prospective validation of an mRNA-based urine test for surveillance of patients with bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqar, U.; Dr., Jaffar, R.; Rafique, T.; Madad, S.; Khan, S.; Ahmed, L. Bladder Cancer in Pakistan Challenges in Early Diagnosis and Multidisciplinary Management. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 31, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.R.; Pervaiz, M.K.; Pervaiz, G. Non-occupational risk factors of urinary bladder cancer in Faisalabad and Lahore, Pakistan. JPMA-J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2012, 62, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, S.; Khan, D.; Faisal, S.; Rauf, F.; Ali, M.O.; Rehman, A. A histopathological and epidemiological study of urothelial carcinoma at a tertiary care centre in Peshawar, Pakistan. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2024, 74, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAU. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (TaT1 and Carcinoma In Situ). Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Bladder Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan, G.A.; Wojcik, E.M.; Nayar, R.; Savic-Prince, S.; Quek, M.L.; Kurtycz, D.F.; Rosenthal, D.L. The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology: The Quest to Develop a Standardized Terminology. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2016, 23, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, S.; Jhaveri, P.; Oza, K.; Shah, C. A histopathological study of urinary bladder neoplasms. Indian J. Pathol. Oncol. 2021, 8, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.T.; Wolfe, D. Tissue Processing and Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining. In Histopathology: Methods and Protocols; Day, C.E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Netto, G.J.; Amin, M.B.; Berney, D.M.; Compérat, E.M.; Gill, A.J.; Hartmann, A.; Menon, S.; Raspollini, M.R.; Rubin, M.A.; Srigley, J.R.; et al. The 2022 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part B: Prostate and Urinary Tract Tumors. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Layton, C. 10—The hematoxylins and eosin. In Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 7th ed.; Suvarna, S.K., Layton, C., Bancroft, J.D., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.S.; Masood, N.; Asif, M.; Ahmed, P.; Shah, Z.U.; Khan, J.S. Expressional analysis of MLH1 and MSH2 in breast cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2019, 43, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.S.; Nawaz, G.; Masood, N. Genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1: Useful determinants for clinical outcome of bladder cancer in Pakistani population. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2017, 18, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurle, R.; Casale, P.; Saita, A.; Colombo, P.; Elefante, G.M.; Lughezzani, G.; Fasulo, V.; Paciotti, M.; Domanico, L.; Bevilacqua, G.; et al. Clinical performance of Xpert Bladder Cancer (BC) Monitor, a mRNA-based urine test, in active surveillance (AS) patients with recurrent non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC): Results from the Bladder Cancer Italian Active Surveillance (BIAS) project. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2215–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacew, A.; Sweis, R.F. FGFR3 alterations in the era of immunotherapy for urothelial bladder cancer. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 575258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sites, A. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2011; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, K.; Biswas, L.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Jana, A.; Basak, T.; Manna, D.; Mandal, S. Clinico-demographic Profile of Carcinoma Urinary Bladder—5-Year Experience from a Tertiary Care Centre of Eastern India. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 15, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.H.; Tseng, W.H.; Huang, S.K.; Liu, C.L.; Wu, Y.C.; Chiu, A.W.; Ong, K.H. Association between Smoking and Overall and Specific Mortality in Patients with Bladder Cancer: A Population-based Study. Bladder Cancer 2022, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kispert, S.; Marentette, J.; McHowat, J. Cigarette smoking promotes bladder cancer via increased platelet-activating factor. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e13981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuto, A.; Citarella, F.; Croghan, I.; Tonini, G. The effects of cigarette smoking extracts on cell cycle and tumor spread: Novel evidence. Future Sci. OA 2019, 5, FSO394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Khan, M.A.; Amin, I.; Butt, M.K. Carcinoma of urinary bladder; Extent of carcinoma of urinary bladder on first presentation and its impact on management. Prof. Med. J. 2017, 24, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Shirodkar, S.P.; Lokeshwar, V.B. Bladder tumor markers: From hematuria to molecular diagnostics–where do we stand? Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008, 8, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakus, D.; Šolić, I.; Jurić, I.; Borovac, J.A.; Šitum, M. The Impact of the Initial Clinical Presentation of Bladder Cancer on Histopathological and Morphological Tumor Characteristics. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanksha, M.; Sandhya, S. Role of FGFR3 in Urothelial Carcinoma. Iran. J. Pathol. 2019, 14, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdiwi, A.Z.; Mousa, H.N.; Mohammad, H. Prognostic value of FGFR3 expression in Urinary bladder cancer. Onkol. I Radioter. 2023, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Suryanti, S.; Agustina, H.; Mulyati, S. The Immunoexpression Profile of FGFR3 and P53 in Punlmp and Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma at Hasan Sadikin General Hospital. Indones. J. Urol. 2020, 27, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader, C.; López, R.; Ferrer, L.; Calderon, R.; Ribera-Cortada, I.; Trias, I.; Cobo-López, S.; Sánchez, S.; Alcaraz, A.; Mengual, L. FGFR3 Immunohistochemistry as a Surrogate Biomarker for FGFR3 Alterations in Urothelial Carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 271, 156028. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Black, P.C.; Goebell, P.J.; Ji, L.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Schmitz-Dräger, B.; Hawes, D.; Czerniak, B.; Minner, S.; Sauter, G. Prognostic markers in pT3 bladder cancer: A study from the international bladder cancer tissue microarray project. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 301.e17–301.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbach, A.; Rogler, A.; Erber, R.; Stoehr, R.; Poulsom, R.; Heidenreich, A.; Schneevoigt, B.S.; Hauke, S.; Hartmann, A.; Knuechel, R. Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) gene amplifications are rare events in bladder cancer. Histopathology 2015, 66, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, Y.; Miladi, M.; Dukare, S.; Boulay, K.; Caudron-Herger, M.; Groß, M.; Backofen, R.; Diederichs, S. A pan-cancer analysis of synonymous mutations. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaissarian, N.M.; Meyer, D.; Kimchi-Sarfaty, C. Synonymous variants: Necessary nuance in our understanding of cancer drivers and treatment outcomes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1072–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Guancial, E.A.; Werner, L.; Bellmunt, J.; Bamias, A.; Choueiri, T.K.; Ross, R.; Schutz, F.A.; Park, R.S.; O’Brien, R.J.; Hirsch, M.S. FGFR3 expression in primary and metastatic urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer Med. 2014, 3, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S.; López-Knowles, E.; Lloreta, J.; Kogevinas, M.; Amorós, A.; Tardón, A.; Carrato, A.; Serra, C.; Malats, N.; Real, F.X. Prospective study of FGFR3 mutations as a prognostic factor in nonmuscle invasive urothelial bladder carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 3664–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elessawy, H.; Abdul-Rasheed, O.F.; Alqanbar, M.F. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 Mutations in Bladder Cancer: A Marker for Early-Stage Diagnosis. AL-Kindy Coll. Med. J. 2025, 21, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.A. FGFR3–a central player in bladder cancer pathogenesis? Bladder Cancer 2020, 6, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gust, K.M.; McConkey, D.J.; Awrey, S.; Hegarty, P.K.; Qing, J.; Bondaruk, J.; Ashkenazi, A.; Czerniak, B.; Dinney, C.P.; Black, P.C. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a rational therapeutic target in bladder cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.S.; Wang, K.; Al-Rohil, R.N.; Nazeer, T.; Sheehan, C.E.; Otto, G.A.; He, J.; Palmer, G.; Yelensky, R.; Lipson, D. Advanced urothelial carcinoma: Next-generation sequencing reveals diverse genomic alterations and targets of therapy. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshmand, S.; Zaucha, R.; Gartrell, B.A.; Lotan, Y.; Hussain, S.A.; Lee, E.K.; Procopio, G.; Galanternik, F.; Naini, V.; Carcione, J. Phase 2 study of the efficacy and safety of erdafitinib in patients (pts) with intermediate-risk non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (IR-NMIBC) with FGFR3/2 alterations (alt) in THOR-2: Cohort 3 interim analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuzillet, Y.; Paoletti, X.; Ouerhani, S.; Mongiat-Artus, P.; Soliman, H.; de The, H.; Sibony, M.; Denoux, Y.; Molinie, V.; Herault, A. A meta-analysis of the relationship between FGFR3 and TP53 mutations in bladder cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48993. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, V.; Singh, M.K.; Shrivastava, A.; Sahu, D.K.; Singh, V.; Singh, M.; Shrivastava, A. Evaluation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) and tumor protein P53 (TP53) as independent prognostic biomarkers in high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cureus 2024, 16, e65816. [Google Scholar]

- Murnyák, B.; Hortobágyi, T. Immunohistochemical correlates of TP53 somatic mutations in cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 64910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, A.A.; Awadalla, A.; Elsayed, A.; Abdullateef, M.; Abol-Enein, H. Prospective validation of clinical usefulness of a novel mRNA-based urine test (Xpert® Bladder Cancer Monitor) for surveillance in non muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 77.e9–77.e16. [Google Scholar]

- Abuhasanein, S. Optimizing the Early Diagnosis Process of Urinary Bladder Cancer. On Standardized Care Pathway, Computed Tomography, Artificial Intelligence, and a Newly Developed Urine-Based Cancer Marker. Ph.D. Thesis, Gothenburg University, Göteborg, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.S.; Sarpong, R.; Khetrapal, P.; Rodney, S.; Mostafid, H.; Cresswell, J.; Watson, D.; Rane, A.; Hicks, J.; Hellawell, G. Does urinary cytology have a role in haematuria investigations? BJU Int. 2019, 123, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kars, M.; Çetin, M.; Toper, M.H.; Filinte, D.; Çam, K. Contemporary Role of Urine Cytology in Bladder Cancer. Bull. Urooncol. 2024, 23, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, E.; Fujita, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Uemura, H.; Nonomura, N. Urinary markers for bladder cancer diagnosis: A review of current status and future challenges. Int. J. Urol. 2024, 31, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordelli, F.; Desai, A.; Dagnino, F.; Contieri, R.; Giuriolo, S.; Paciotti, M.; Fasulo, V.; Mancon, S.; Maffei, D.; Avolio, P.P. Xpert Bladder Cancer Detection in Emergency Setting Assessment (XESA Project): A Prospective, Single-centre Trial. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 71, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.-B.; Meng, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhou, Z.-Z.; Li, H.-L.; Tian, X.-P.; Huang, W.-J. Artificial intelligence alphafold model for molecular biology and drug discovery: A machine-learning-driven informatics investigation. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.-B.; Liu, D.-Y.; Fang, X.-J.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, Z.-Z.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Luo, L.-L.; Li, H.-L.; Cai, X.-Y. Current concerns and future directions of large language model chatGPT in medicine: A machine-learning-driven global-scale bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Study Detection | |

|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 62 | (85) |

| Female | 11 | (15) |

| Mean age, yr (Range) | ||

| Overall | 63 | (21–90) |

| Smoking | ||

| Smoker | 59 | (81) |

| Non-Smoker | 14 | (19) |

| Family history | ||

| Yes | 6 | (8) |

| No | 67 | (92) |

| Hematuria | ||

| Yes | 64 | (88) |

| No | 9 | (12) |

| Dysuria/urgency | ||

| Yes | 47 | (64) |

| No | 26 | (36) |

| Cystoscopy | ||

| Positive | 70 | (96) |

| Negative | 3 | (4) |

| Urine cytology | ||

| Positive | 24 | (33) |

| Negative | 49 | (67) |

| Xpert BCM | ||

| Positive | 63 | (86.3) |

| Negative | 10 | (13.7) |

| Tumour grade | ||

| Carcinoma in situ | 3 | (4) |

| Low-Grade | 23 | (32) |

| High-Grade | 47 | (64) |

| TNM stage (T stage) | ||

| pTis | 3 | (4) |

| pTa | 24 | (33) |

| pT1 | 27 | (37) |

| pT2 | 18 | (25) |

| pT3 | 1 | (1) |

| Primary tumour/recurrence | ||

| Primary | 56 | (77) |

| Recurrence | 17 | (23) |

| Marker | Category | Low n (%) | High n (%) | p-Value (Grade) | NMIBC n (%) | MIBC n (%) | p-Value (Stage) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGFR3 | Weak | 6 (13%) | 37 (82%) | 0.0008 | 28 (62%) | 17 (38%) | 0.012 |

| Moderate | 11 (58%) | 8 (42%) | 5 (83%) | 1 (17%) | |||

| Strong | 6 (67%) | 2 (22%) | 21 (95%) | 1 (5%) | |||

| p53 | Mutant+ | 4 (8%) | 45 (87%) | <0.0001 | 32 (63%) | 19 (37%) | 0.0024 |

| Wild– | 19 (90%) | 2 (10%) | 22 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asif, M.; Rashid, F.A.; Malik, S.S.; Khan, D.A.; Sajid, M.T.; Gul, A.; Khadim, M.T. Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of FGFR3, TP53 Mutation and Urinary Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma in Pakistani Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8526. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238526

Asif M, Rashid FA, Malik SS, Khan DA, Sajid MT, Gul A, Khadim MT. Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of FGFR3, TP53 Mutation and Urinary Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma in Pakistani Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8526. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238526

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsif, Muhammad, Faiza Abdul Rashid, Saima Shakil Malik, Dilshad Ahmed Khan, Muhammad Tanveer Sajid, Asma Gul, and Muhammad Tahir Khadim. 2025. "Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of FGFR3, TP53 Mutation and Urinary Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma in Pakistani Cohort" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8526. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238526

APA StyleAsif, M., Rashid, F. A., Malik, S. S., Khan, D. A., Sajid, M. T., Gul, A., & Khadim, M. T. (2025). Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of FGFR3, TP53 Mutation and Urinary Biomarkers in Urothelial Carcinoma in Pakistani Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8526. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238526