Early Conversion to Once-Daily MeltDose® Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) in Liver Transplant Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

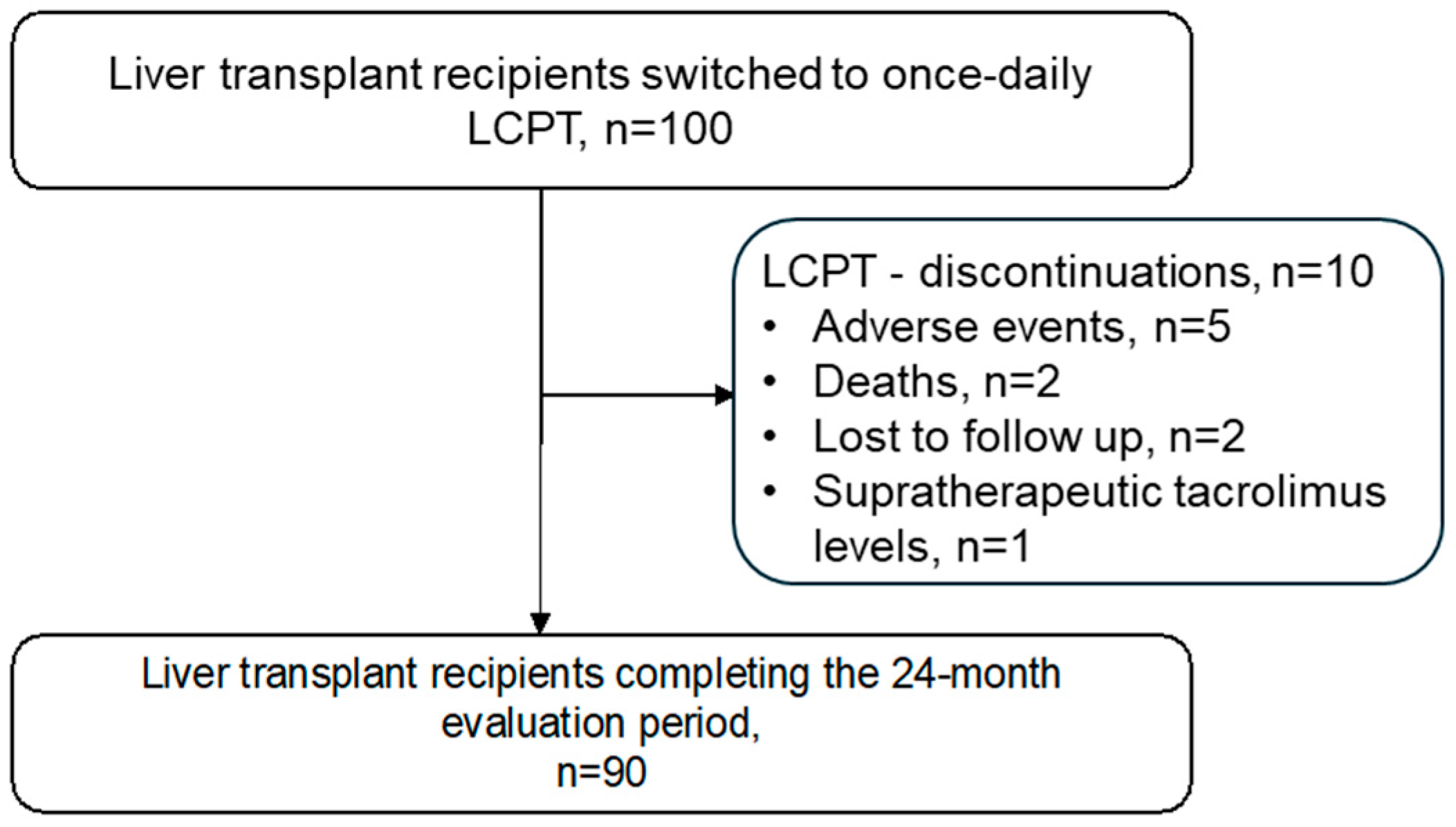

3.1. Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Effectiveness, Adverse Events and Causes of LCPT Discontinuation

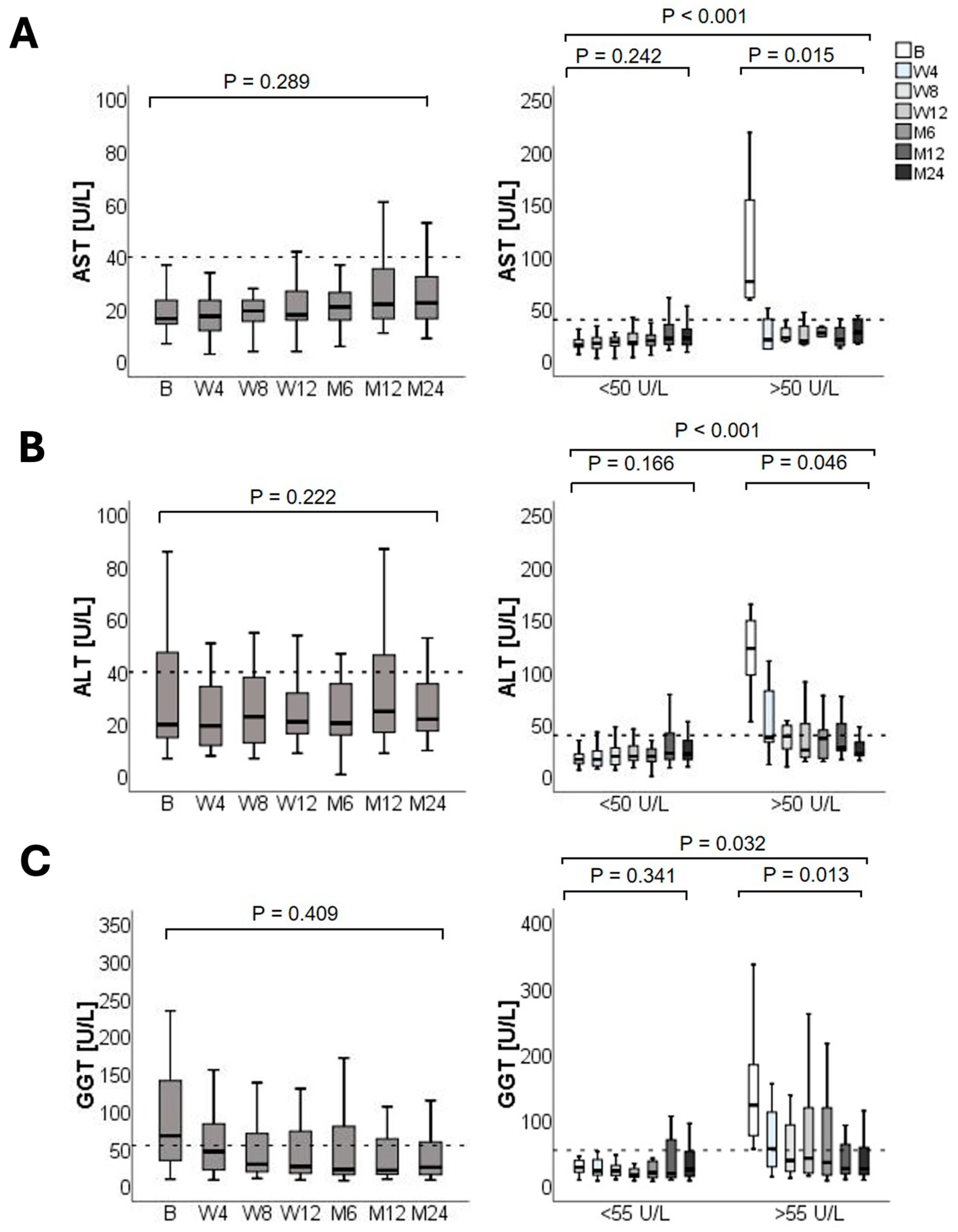

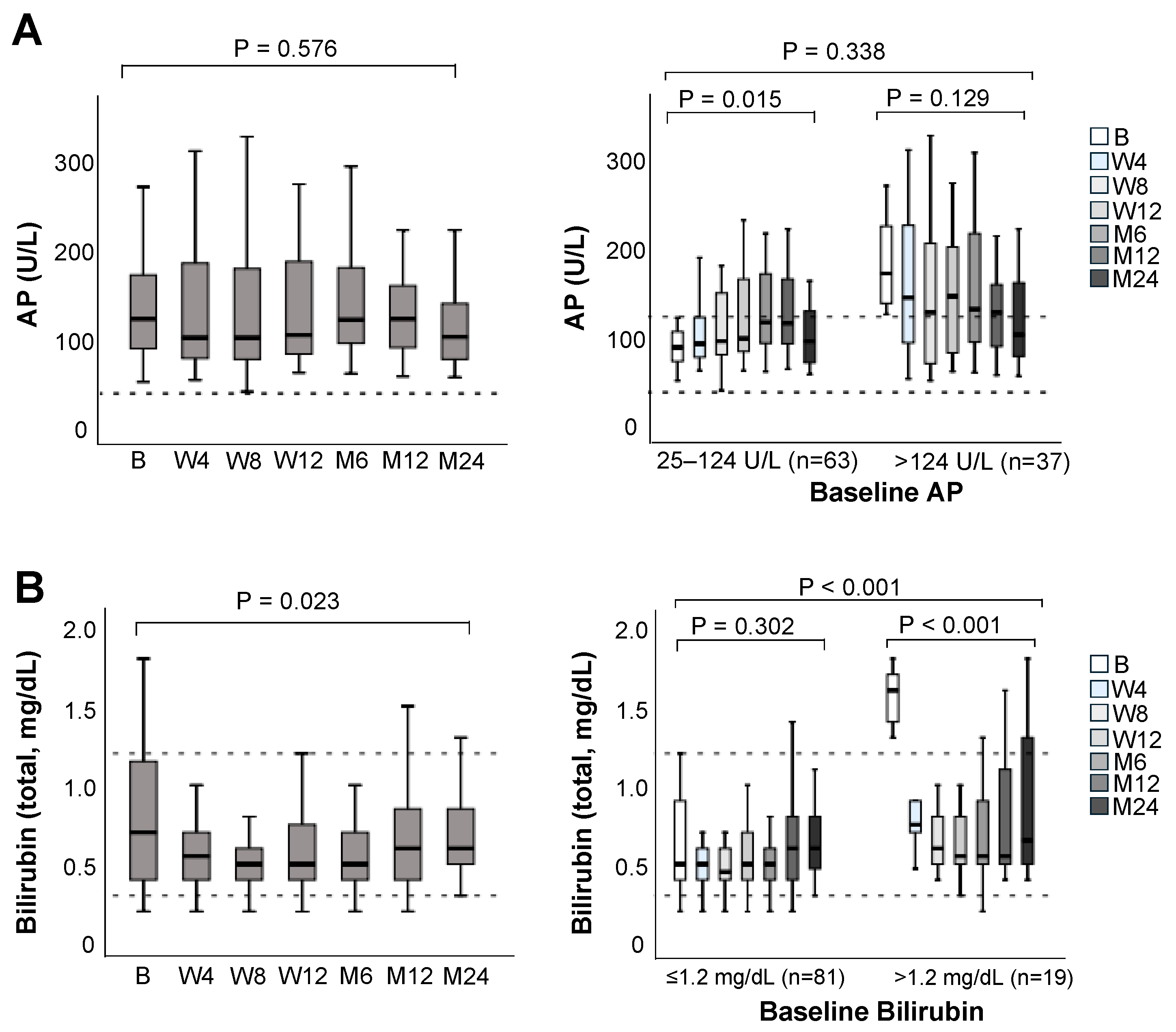

3.3. Liver Graft Function

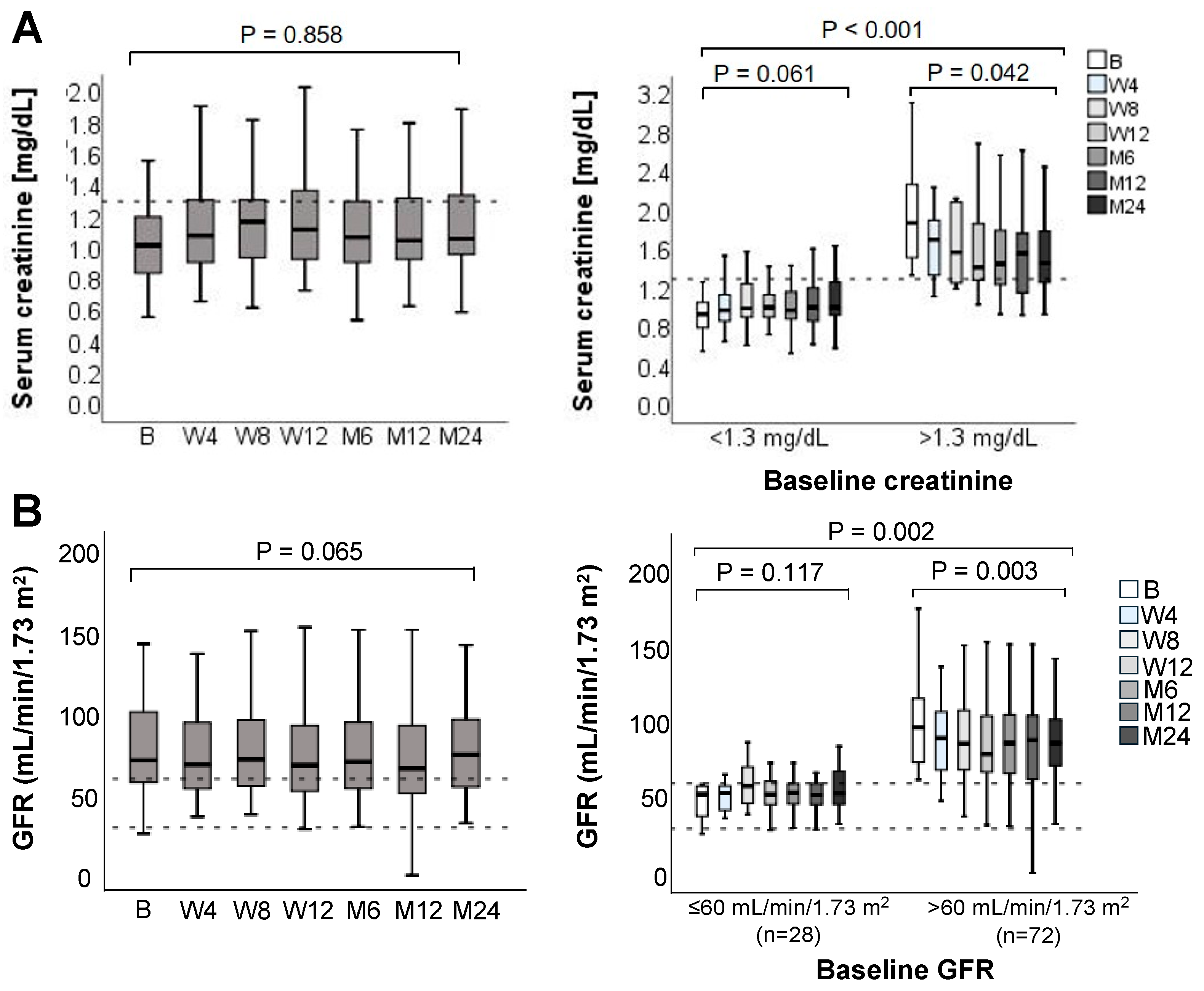

3.4. Renal Function

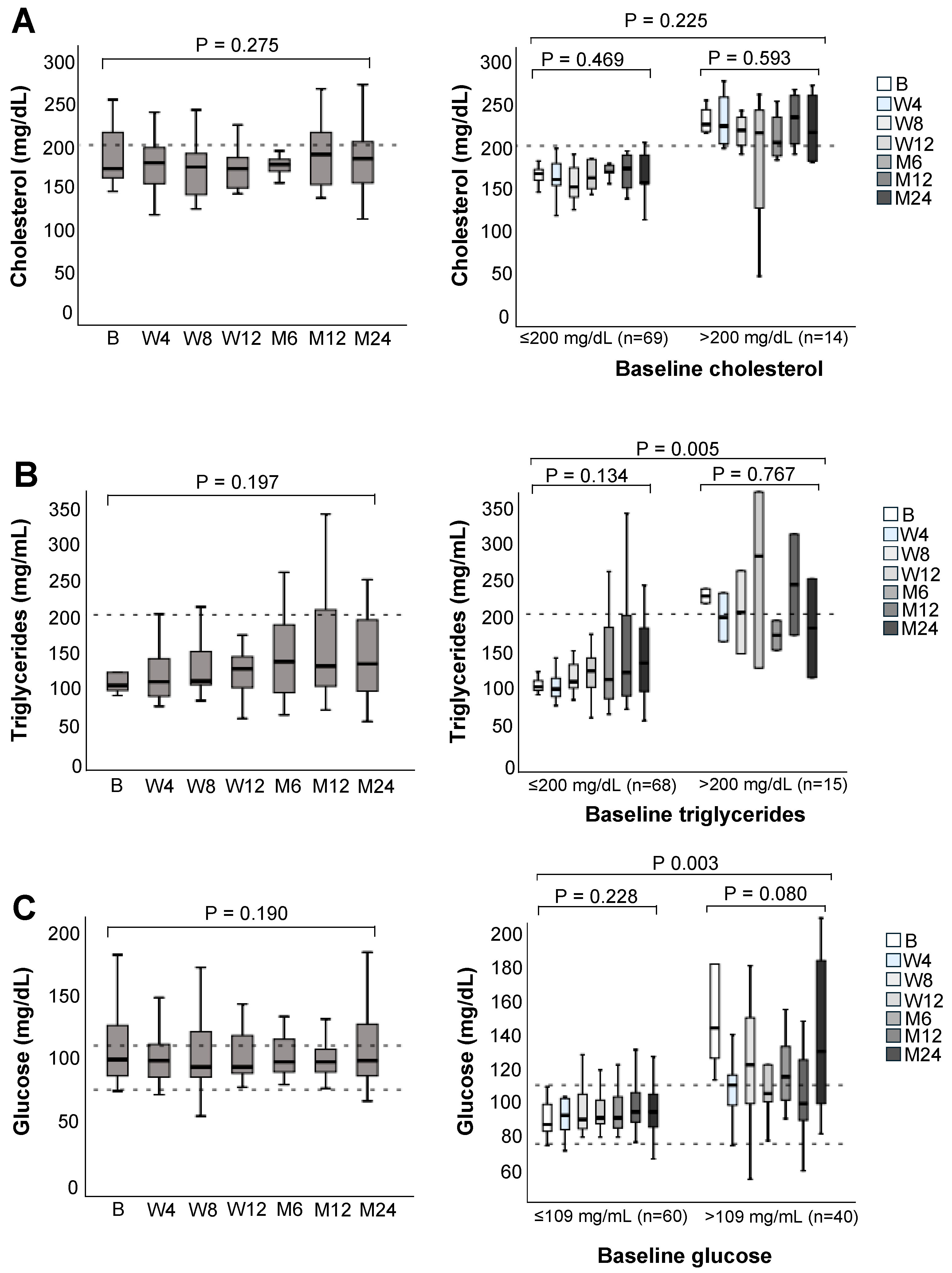

3.5. Lipid and Glucose Metabolism

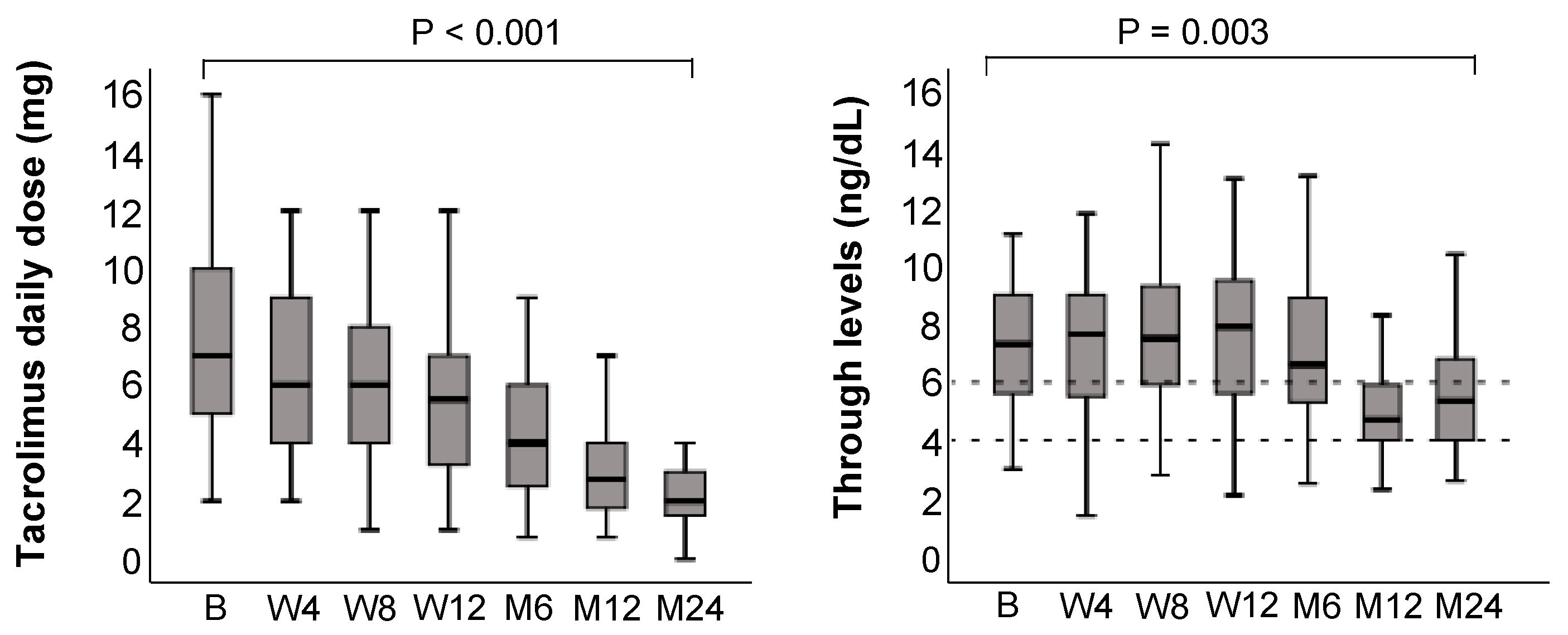

3.6. Tacrolimus Trough Levels

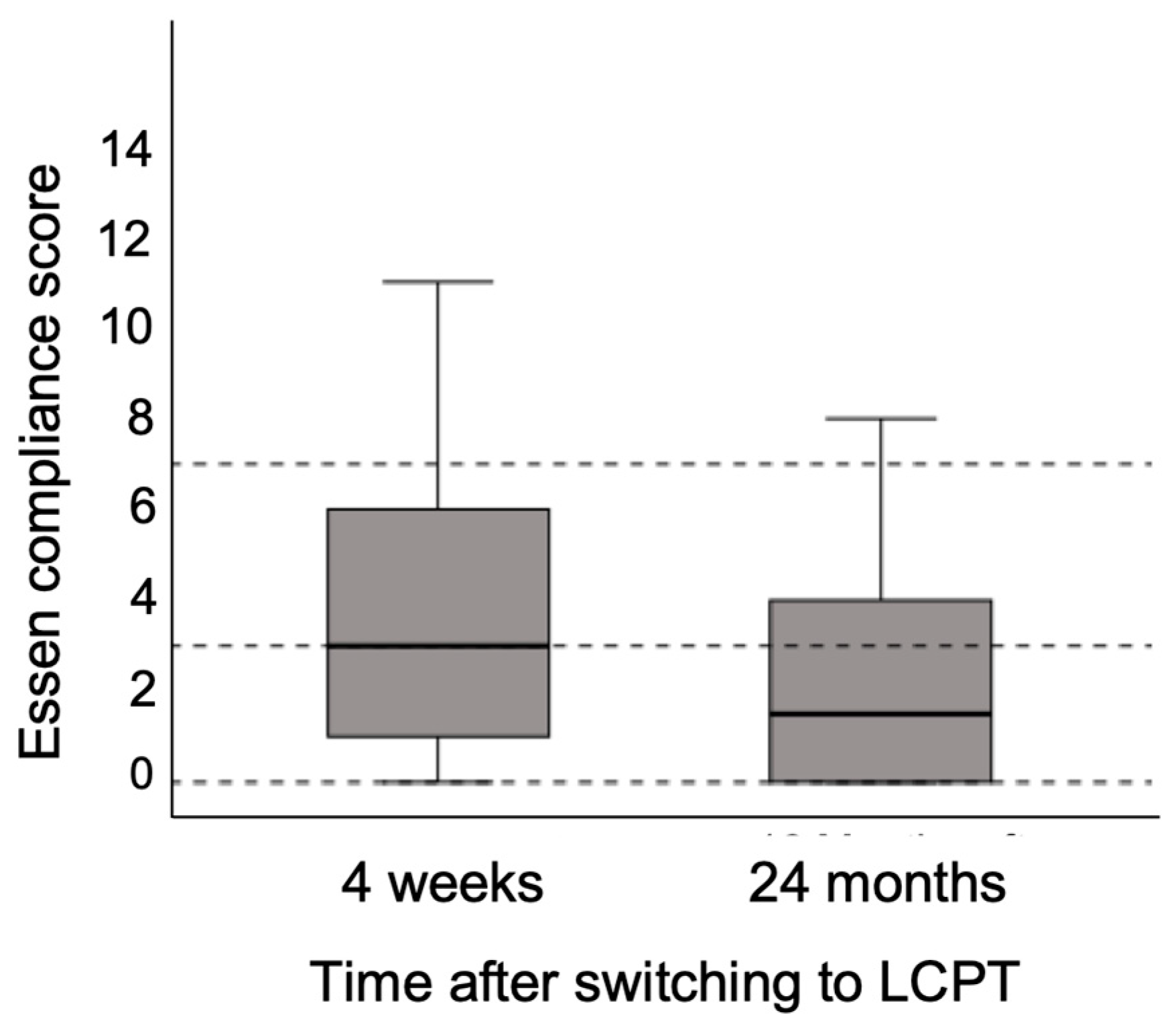

3.7. Adherence to Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Transaminase |

| AP | Alkaline Phosphatases |

| AST | Aspartate Transferase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CNI | Calcineurin Inhibitor |

| ESC | Essen Compliance Score |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl Transferase |

| IR-Tac | Immediate Release Tacrolimus |

| LCPT | MeltDose® Extended-release Tacrolimus |

| LT | Liver Transplant |

| PLTDM | Post-liver Transplantation Diabetes Mellitus |

| PR-Tac | Prolonged-release tacrolimus |

References

- Angelico, R.; Sensi, B.; Manzia, T.M.; Tisone, G.; Grassi, G.; Signorello, A.; Milana, M.; Lenci, I.; Baiocchi, L. Chronic rejection after liver transplantation: Opening the Pandora’s box. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 7771–7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano-Loza, A.J.; Rodríguez-Perálvarez, M.L.; Pageaux, G.P.; Sanchez-Fueyo, A.; Feng, S. Liver transplantation immunology: Immunosuppression, rejection, and immunomodulation. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlister, V.C.; Haddad, E.; Renouf, E.; Malthaner, R.A.; Kjaer, M.S.; Gluud, L.L. Cyclosporin versus tacrolimus as primary immunosuppressant after liver transplantation: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Transplant. 2006, 6, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, M.; Levitsky, J.; Aqel, B.; O’Grady, J.; Hemibach, J.; Rinella, M.; Fung, J.; Ghabril, M.; Thomason, R.; Burra, P.; et al. International Liver Transplantation Society Consensus Statement on Immunosuppression in Liver Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2018, 102, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burra, P.; Burroughs, A.; Graziadei, I.; Pirenne, J.; Valdecasas, J.C.; Muiesan, P.; Samuel, D.; Forns, X. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 433–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongprayoon, C.; Hansrivijit, P.; Kovvuru, K.; Kanduri, S.R.; Bathini, T.; Pivovarova, A.; Smith, J.R.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Impacts of high intra-and inter-individual variability in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics and fast tacrolimus metabolism on outcomes of solid organ transplant recipients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, K. Metabolism of tacrolimus (FK506) and recent topics in clinical pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2007, 22, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gelder, T. Drug Interactions with Tacrolimus. Drug Saf. 2002, 25, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colmenero, J.; Gastaca, M.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Soria, C.; Lázaro, E.; Plasencia, I. Risk Factors for Non-Adherence to Medication for Liver Transplant Patients: An Umbrella Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, S.; Nigro, V.; Weinberg, J.; Woodle, E.S.; Alloway, R.R. A Steady-State Head-to-Head Pharmacokinetic Comparison of All FK-506 (Tacrolimus) Formulations (ASTCOFF): An Open-Label, Prospective, Randomized, Two-Arm, Three-Period Crossover Study. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, M.; Van Gelder, T.; Åsberg, A.; Haufroid, V.; Hesselink, D.A.; Langman, L.; Lemaitre, F.; Marquet, P.; Seger, C.; Shipkova, M.; et al. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Tacrolimus-Personalized Therapy: Second Consensus Report. Ther. Drug Monit. 2019, 41, 261–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolmit, P.; Davies, M.H. Tacrolimus in liver transplantation. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 1999, 8, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astellas Pharma Europe. Summary of Product Characteristics of Advagraf; Astellas Pharma Europe: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Toti, L.; Manzia, T.M.; Blasi, F.; Lenci, I.; Baiocchi, L.; Toschi, N.; Tisone, G. Renal Function, Adherence and Quality of Life Improvement After Conversion from Immediate to Prolonged-Release Tacrolimus in Liver Transplantation: Prospective Ten-Year Follow-Up Study. Transpl. Int. 2022, 35, 10384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, A.; Tredger, J.M.; Heneghan, M.; Agarwal, K.; Samyn, M.; Heaton, N.D.; O’Grady, J.G.; Aluvihare, V.R. Performance of modified-release tacrolimus after conversion in liver transplant patients indicates potentially favorable outcomes in selected cohorts. Liver Transplant. 2015, 21, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langone, A.; Steinberg, S.M.; Gedaly, R.; Chan, L.K.; Shah, T.; Sethi, K.D.; Nigro, V.; Morgan, J.C. Switching STudy of Kidney TRansplant PAtients with Tremor to LCP-TacrO (STRATO): An open-label, multicenter, prospective phase 3b study. Clin. Transplant. 2015, 29, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Thaker, S.; West-Thielke, P.; Elmasri, A.; Chan, C. Evaluating the conversion to extended-release tacrolimus from immediate-release tacrolimus in liver transplant recipients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Einsiedel, J.; Thölking, G.; Wilms, C.; Vorona, E.; Bokemeyer, A.; Schmidt, H.H.; Kabar, I.; Hüsing-Kabar, A. Conversion from standard-release tacrolimus to meltdose® tacrolimus (LCPT) improves renal function after liver transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giral, M.; Grimbert, P.; Morin, B.; Bouvier, N.; Buchler, M.; Dantal, J.; Garrigue, V.; Bertrand, D.; Kamar, N.; Malvezzi, P.; et al. Impact of Switching from Immediate- or Prolonged-Release to Once-Daily Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) on Tremor in Stable Kidney Transplant Recipients: The Observational ELIT Study. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 11571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloxis Pharmaceuticals A/S. Summary of Product Characteristics of Envarsus XR; Veloxis Pharmaceuticals A/S: Hørsholm, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baraldo, M. Meltdose Tacrolimus Pharmacokinetics. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.; Delaval, G.; Kimmoun, E.; Allaire, M.; Salamé, E.; Dumortier, J. Conversion from once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus to once-daily extended-release tacrolimus in stable liver transplant recipients. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2018, 16, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willuweit, K.; Frey, A.; Hörster, A.; Saner, F.; Herzer, K. Real-world administration of once-daily MeltDose® prolonged-release tacrolimus (LCPT) allows for dose reduction of tacrolimus and stabilizes graft function following liver transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, I.; Gómez Bravo, M.Á.; Otero, A.; Lladó, L.; Montero, J.L.; González Dieguez, L.; Graus, J.; Pons Miñano, J.A. Effectiveness and safety of once-daily tacrolimus formulations in de novo liver transplant recipients: The PRETHI study. Clin. Transplant. 2023, 37, e15105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBay, D.A.; Teperman, L.; Ueda, K.; Silverman, A.; Chapman, W.; Alsina, A.E.; Tyler, C.; Stevens, D.R. Pharmacokinetics of Once-Daily Extended-Release Tacrolimus Tablets Versus Twice-Daily Capsules in De Novo Liver Transplant. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2019, 8, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alloway, R.R.; Eckhoff, D.E.; Washburn, W.K.; Teperman, L.W. Conversion from twice daily tacrolimus capsules to once daily extended-release tacrolimus (LCP-Tacro): Phase 2 trial of stable liver transplant recipients. Liver Transplant. 2014, 20, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Zaki, R.; Sadeh, J.; Knorr, J.P.; Gallagher, M.; Parsikia, A.; Navarro, V. Improved Medication Adherence with the Use of Extended-Release Tacrolimus in Liver Transplant Recipients: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Transplant. 2023, 2023, 7915781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisky, D.E.; Green, L.W.; Levine, D.M. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med. Care 1986, 24, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türk, T.F.G.; Jagla, M.; Haferkamp, L.; Reimer, J.; Kribben, A.; Witzke, O. Development of the Essen compliance score—Measurement of adherence in kidney transplant patients. Am. J. Transpl. 2009, 9 (Suppl. 2), A296. [Google Scholar]

- Thölking, G.; Siats, L.; Fortmann, C.; Koch, R.; Hüsing, A.; Cicinnati, V.R.; Gerth, H.U.; Wolters, H.H.; Anthoni, C.; Pavenstädt, H.; et al. Tacrolimus concentration/dose ratio is associated with renal function after liver transplantation. Ann. Transplant. 2016, 21, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, M.B.; van Hoek, B.; Polak, W.G.; Alwayn, I.P.J.; de Winter, B.C.M.; Murad, S.D.; Verhey-Hart, E.; Elshove, L.; Erler, N.S.; Hesselink, D.A.; et al. Modifying Tacrolimus-related Toxicity After Liver Transplantation Comparing Life Cycle Pharma Tacrolimus Versus Extended-released Tacrolimus: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial. Transplant. Direct 2024, 10, E1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, T.; Gyoeri, G.; Salat, A.; Mejzlík, V.; Berlakovich, G. A Multi-Centre Non-Interventional Study to Assess the Tolerability and Effectiveness of Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) in De Novo Liver Transplant Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding-Theobald, E.; Kriss, M. Evaluation and management of abnormal liver enzymes in the liver transplant recipient: When, why, and what now? Clin. Liver Dis. 2023, 21, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziolkowski, J.; Paczek, L.; Senatorski, G.; Niewczas, M.; Oldakowska-Jedynak, U.; Wyzgal, J.; Sanko-Resmer, J.; Pilecki, T.; Zieniewicz, K.; Nyckowski, P.; et al. Renal function after liver transplantation: Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Transplant. Proc. 2003, 35, 2307–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, R.C.; Hidalgo, R.; Zurstrassen, M.P.V.C.; Fonseca, L.E.P.; Pandullo, F.L.; Rezende, M.B.; Meira-Filho, S.P.; Ferraz-Neto, B.H. Impact of Renal Failure on Liver Transplantation Survival. Transplant. Proc. 2008, 40, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleisner, A.L.; Jung, H.; Lentine, K.L.; Tuttle-Newhall, J. Renal Dysfunction in Liver Transplant Candidates: Evaluation, Classification and Management in Contemporary Practice. J. Nephrol. Ther. 2012, (Suppl. 4), 006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, F.; Golfieri, L.; Nascimbeni, F.; Andreone, P.; Gitto, S. Metabolic Disorders in Liver Transplant Recipients: The State of the Art. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Jaramillo, M.J.; Cárdenas-Mojica, A.A.; Gaete, P.V.; Mendivil, C.O. Post-Liver Transplantation Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Relevance and Approach to Treatment. Diabetes Ther. 2018, 9, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Characteristics | LCPT (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Recipient demographics | |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 63 (63) |

| Age, years, median [range] | 52 [18–69] |

| Switch to LCPT, days, median (range) | 27 [10–276] |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range) | 23 [16–36] |

| Indication for liver transplantation, n (%) | |

| Autoimmune liver diseases (PBC, PSC, AIH) | 27 (27) |

| Alcoholic steatohepatitis | 21 (21) |

| Acute Liver Failure | 8 (8) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | 8 (8) |

| HCC due to hepatitis C Virus | 8 (8) |

| HCC due to hepatitis B virus (HBV) | 1 (1) |

| Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis | 4 (4) |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis of the liver | 4 (4) |

| HBV | 4 (4) |

| Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease | 4 (4) |

| Secondary sclerosing cholangitis | 3 (3) |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 2 (2) |

| HCV and HBV | 1 (1) |

| Other | 5 (5) |

| Adverse Events, n (%) | LCPT (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Rejection reaction | 3 (3) |

| Transplant failure | 1 (1) |

| Renal insufficiency | 7 (7) |

| Renal failure | 5 (5) |

| Gastrointestinal complications | 28 (28) |

| Neurological symptoms | 28 (28) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 26 (26) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 22 (22) |

| Fatigue | 18 (18) |

| Procedural complications | 17 (17) |

| Blood count change | 13 (13) |

| Respiratory organ, thorax, and mediastinal disorders | 11 (11) |

| Infections | 12 (12) |

| Renal and urinary tract disorders | 11 (11) |

| Vascular complications | 9 (9) |

| Elevated transaminases | 5 (5) |

| Other adverse events | 6 (6) |

| Causes of LCPT discontinuation, n (%) | |

| Hair loss | 1 (1) |

| Pruritus | 1 (1) |

| Tremor | 1 (1) |

| Alopecia areata, tremor, reduced finger sensitivity, restlessness, sleep disorders | 1 (1) |

| Supratherapeutic tacrolimus levels | 1 (1) |

| Death | 2 (2) |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 (2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jochheim, L.S.; Hörster, A.; Frey, A.; Herzer, K.; Hoyer, D.P.; Nowak, K.M.; Neumann, U.P.; Schmidt, H.; Rashidi-Alavijeh, J.; Passenberg, M.; et al. Early Conversion to Once-Daily MeltDose® Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) in Liver Transplant Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238530

Jochheim LS, Hörster A, Frey A, Herzer K, Hoyer DP, Nowak KM, Neumann UP, Schmidt H, Rashidi-Alavijeh J, Passenberg M, et al. Early Conversion to Once-Daily MeltDose® Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) in Liver Transplant Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238530

Chicago/Turabian StyleJochheim, Leonie S., Anne Hörster, Alexandra Frey, Kerstin Herzer, Dieter Paul Hoyer, Knut M. Nowak, Ulf P. Neumann, Hartmut Schmidt, Jassin Rashidi-Alavijeh, Moritz Passenberg, and et al. 2025. "Early Conversion to Once-Daily MeltDose® Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) in Liver Transplant Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238530

APA StyleJochheim, L. S., Hörster, A., Frey, A., Herzer, K., Hoyer, D. P., Nowak, K. M., Neumann, U. P., Schmidt, H., Rashidi-Alavijeh, J., Passenberg, M., & Willuweit, K. (2025). Early Conversion to Once-Daily MeltDose® Extended-Release Tacrolimus (LCPT) in Liver Transplant Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238530