Effect of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Certainty Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

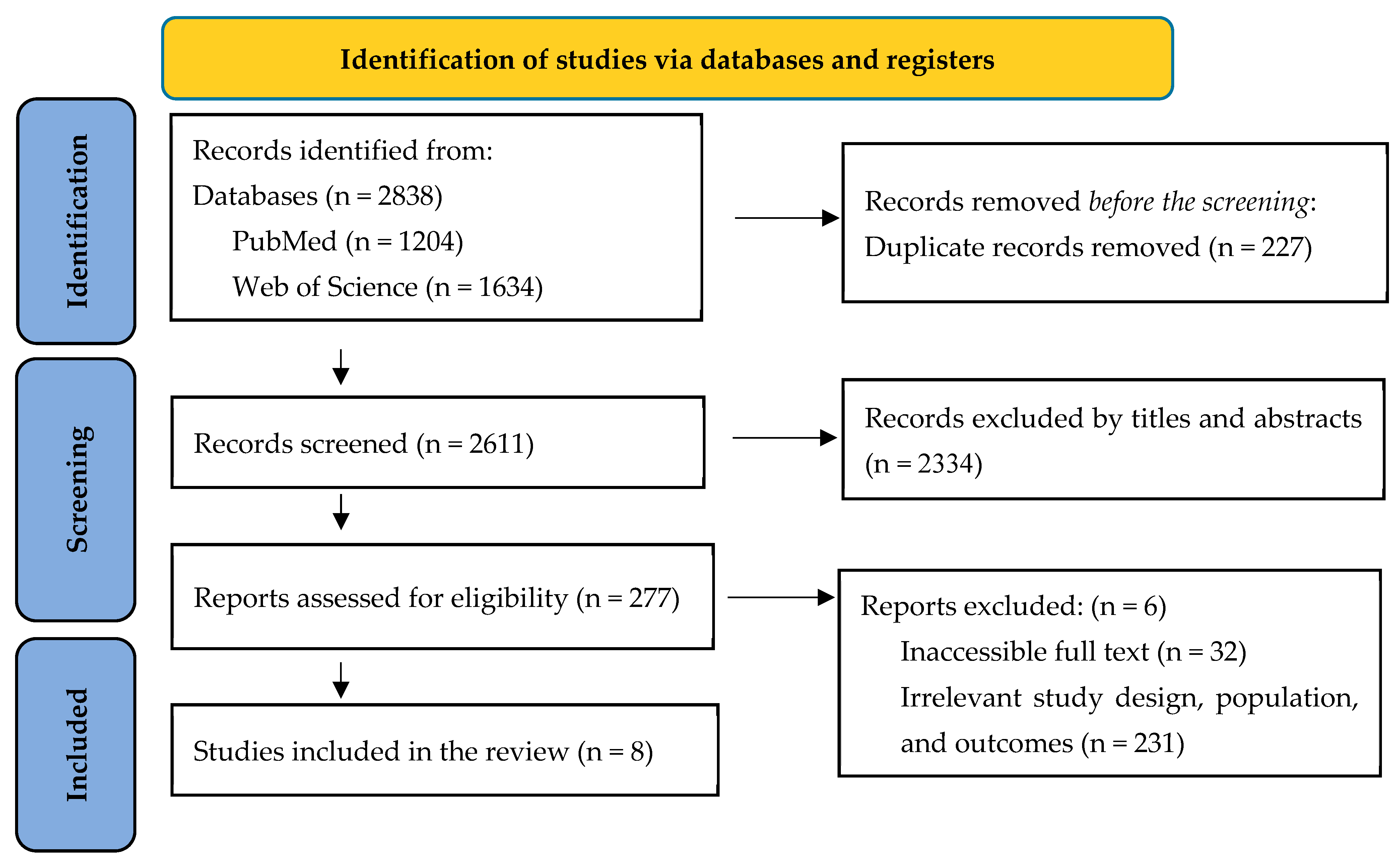

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Preterm Delivery Outcome

3.4. Pregnancy Loss Outcome

3.5. Placental Abruption Outcome

3.6. Live Birth Rates and Ongoing Pregnancy

3.7. Maternal Complications

3.8. Neonatal Outcomes

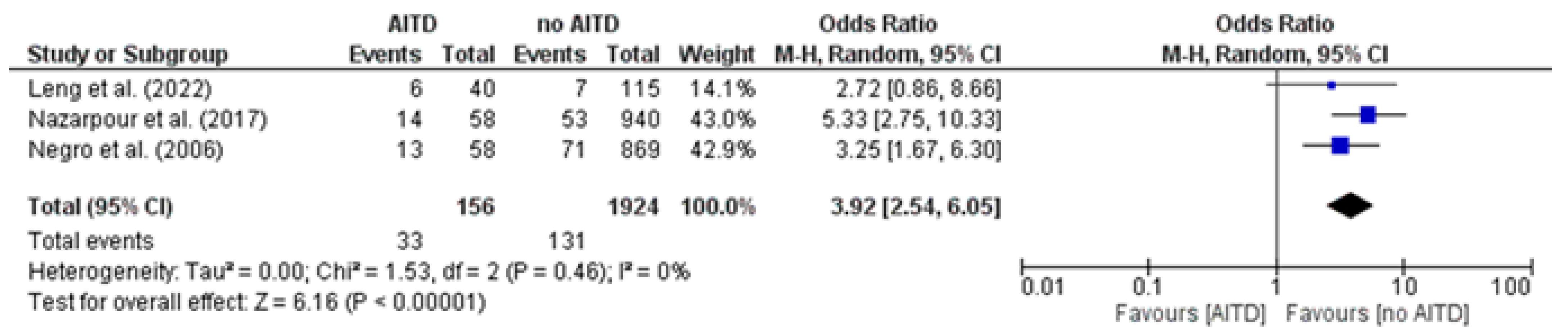

3.9. Preterm Delivery Rates: AITD Patients vs. Non-AITD Patients

3.10. Placental Abruption: AITD Patients vs. Non-AITD Patients

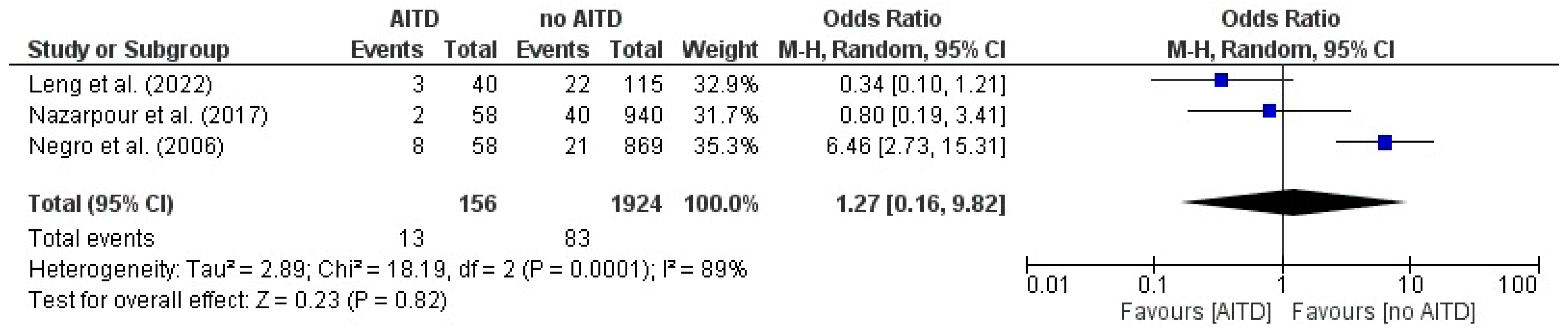

3.11. Miscarriage: AITD Patients vs. Non-AITD Patients

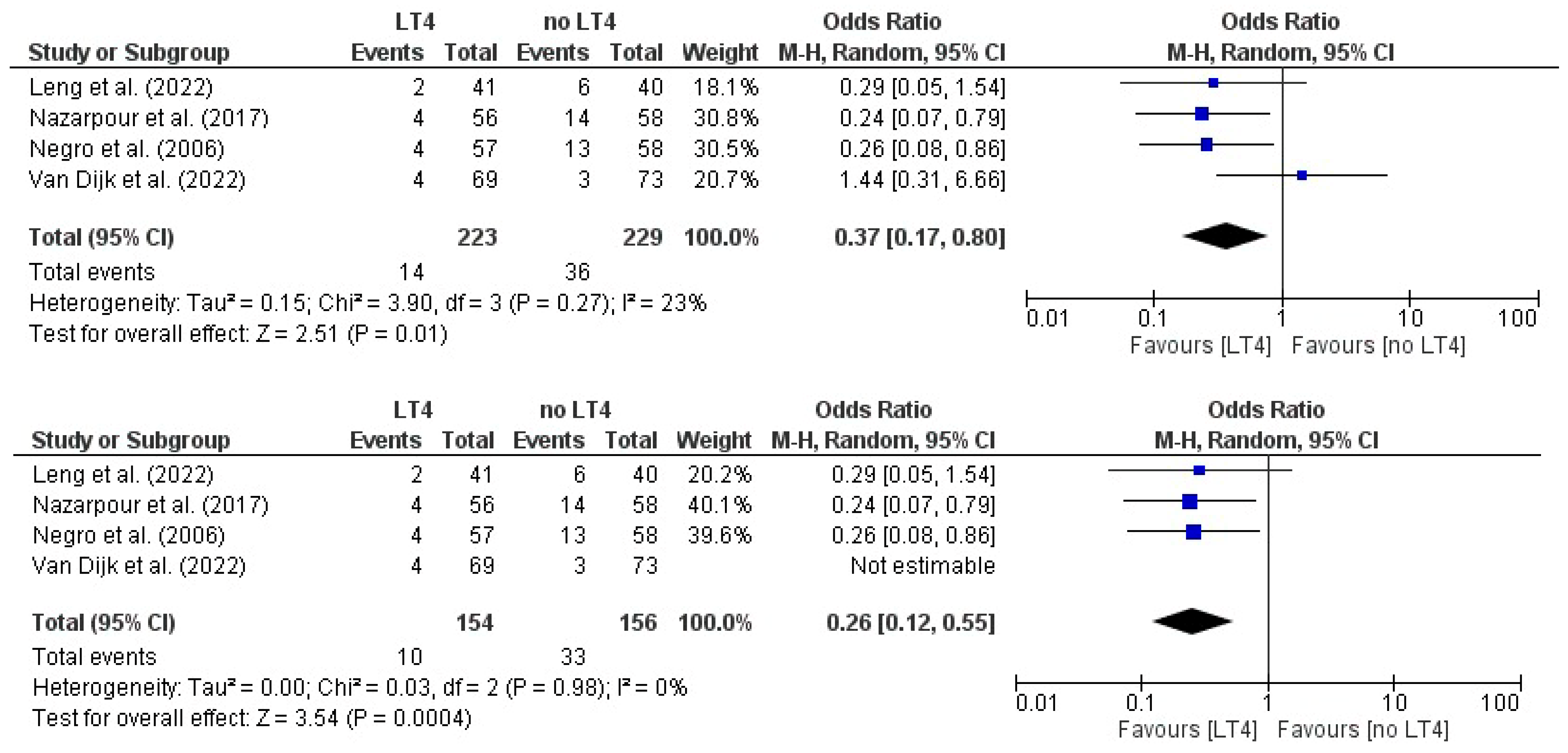

3.12. Miscarriage: AITD Patients Treated with LT4 vs. Non-Treated Patients

3.13. Preterm Delivery: AITD Patients Treated with LT4 vs. Non-Treated Patients

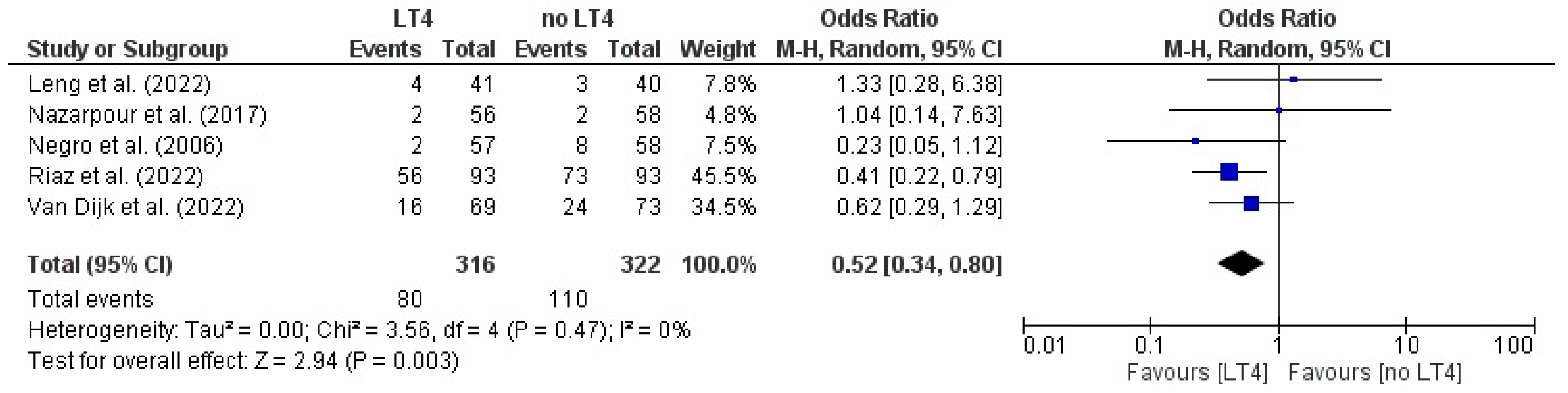

3.14. Live Birth: AITD Patients Treated with LT4 vs. Non-Treated Patients

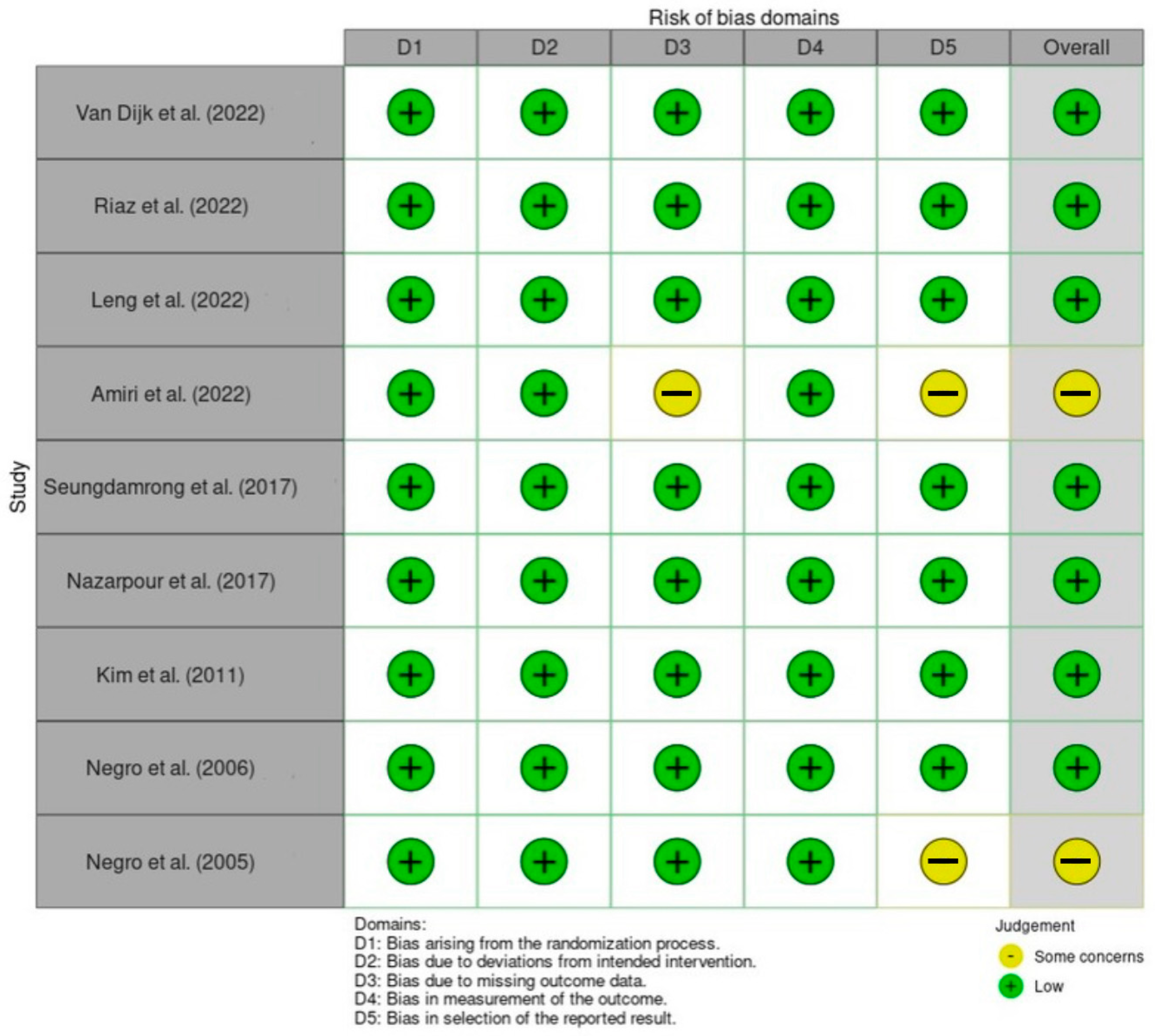

3.15. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.16. Certainty Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AITD | Autoimmune Thyroid Disease |

| TPOAb | Thyroid Peroxidase Antibody |

| TgAb | Thyroglobulin Antibody |

| LT4 | Levothyroxine |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Tańska, K.; Gietka-Czernel, M.; Glinicki, P.; Kozakowski, J. Thyroid autoimmunity and its negative impact on female fertility and maternal pregnancy outcomes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 13, 1049665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, S.; Pearce, E.N. Autoimmune thyroid disease during pregnancy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, A.; Ferrari, S.M.; Corrado, A.; Di Domenicantonio, A.; Fallahi, P. Autoimmune thyroid disorders. Autoimmun. Rev. 2015, 14, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.D.L.; Obeng-Gyasi, B.; Hall, J.E.; Shekhar, S. The Thyroid Hormone Axis and Female Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumru, P.; Erdogdu, E.; Arisoy, R.; Demirci, O.; Ozkoral, A.; Ardic, C.; Ertekin, A.A.; Erdogan, S.; Ozdemir, N.N. Effect of thyroid dysfunction and autoimmunity on pregnancy outcomes in low risk population. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 291, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogović Crnčić, T.; Ćurko-Cofek, B.; Batičić, L.; Girotto, N.; Tomaš, M.I.; Kršek, A.; Krištofić, I.; Štimac, T.; Perić, I.; Sotošek, V.; et al. Autoimmune Thyroid Disease and Pregnancy: The Interaction Between Genetics, Epigenetics and Environmental Factors. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joukhadar, J.; Nevers, T.; Kalkunte, S. New frontiers in reproductive immunology research: Bringing bedside problems to the bench. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 7, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, F.; Dabbaghmanesh, M.H.; Ghaemi, S.Z.; Forouhari, S.; Ranjbar Omrani, G.; Bakhshayeshkaram, M. Thyroid Function in Pregnancy and Its Influences on Maternal and Fetal Outcomes. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 12, e19378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagoe, C.E. Rheumatic Symptoms in Autoimmune Thyroiditis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2015, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männistö, T.; Vääräsmäki, M.; Pouta, A.; Hartikainen, A.-L.; Ruokonen, A.; Surcel, H.-M.; Bloigu, A.; Järvelin, M.-R.; Suvanto-Luukkonen, E. Perinatal Outcome of Children Born to Mothers with Thyroid Dysfunction or Antibodies: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbassi-Ghanavati, M.; Casey, B.M.; Spong, C.Y.; McIntire, D.D.; Halvorson, L.M.; Cunningham, F.G. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korevaar, T.I.M.; Derakhshan, A.; Taylor, P.N.; Meima, M.; Chen, L.; Bliddal, S.; Carty, D.M.; Meems, M.; Vaidya, B.; Shields, B.; et al. Association of Thyroid Function Test Abnormalities and Thyroid Autoimmunity With Preterm Birth. JAMA 2019, 322, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagnaro-Green, A. Maternal Thyroid Disease and Preterm Delivery. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Escobar, G.M.; Obregón, M.J.; del Rey, F.E. Maternal thyroid hormones early in pregnancy and fetal brain development. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 18, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moog, N.K.; Entringer, S.; Heim, C.; Wadhwa, P.D.; Kathmann, N.; Buss, C. Influence of maternal thyroid hormones during gestation on fetal brain development. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneventi, F.; De Maggio, I.; Bellingeri, C.; Cavagnoli, C.; Spada, C.; Boschetti, A.; Magri, F.; Spinillo, A. Thyroid autoimmunity and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Endocrine 2022, 76, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.A. The Preparation of Future Statistically Oriented Physicians: A Single-Center Experience in Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2024, 60, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, M.M.; Vissenberg, R.; Fliers, E.; van der Post, J.A.M.; van der Hoorn, M.-L.P.; de Weerd, S.; Kuchenbecker, W.K.; Hoek, A.; Sikkema, J.M.; Verhoeve, H.R.; et al. Levothyroxine in euthyroid thyroid peroxidase antibody positive women with recurrent pregnancy loss (T4LIFE trial): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, R.; Formoso, G.; Mangieri, T.; Pezzarossa, A.; Dazzi, D.; Hassan, H. Levothyroxine Treatment in Euthyroid Pregnant Women with Autoimmune Thyroid Disease: Effects on Obstetrical Complications. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 2587–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, R.; Mangieri, T.; Coppola, L.; Presicce, G.; Casavola, E.C.; Gismondi, R.; Locorotondo, G.; Caroli, P.; Pezzarossa, A.; Dazzi, D.; et al. Levothyroxine treatment in thyroid peroxidase antibody-positive women undergoing assisted reproduction technologies: A prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Rana, M.; Mushtaq, A.; Ahmad, U.R.; Khawaja, S.R.; Rasheed, A. Effect of Treatment of Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction on Pregnancy Outcome in Patients with 1st Trimester Recurrent Miscarriages. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Levothyroxine treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism improves the rate of live births in pregnant women with recurrent pregnancy loss: A randomized clinical trial. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2022, 38, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Nazarpour, S.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Sheidaei, A.; Azizi, F. The targeted high-risk case-finding approach versus universal screening for thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy: Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and/or thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) test? J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2022, 45, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarpour, S.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Simbar, M.; Tohidi, M.; Alavi Majd, H.; Azizi, F. Effects of levothyroxine treatment on pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with autoimmune thyroid disease. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 176, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-H.; Ahn, J.-W.; Kang, S.P.; Kim, S.-H.; Chae, H.-D.; Kang, B.-M. Effect of levothyroxine treatment on in vitro fertilization and pregnancy outcome in infertile women with subclinical hypothyroidism undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaratinam, S.; Tan, A.; Knox, E.; Kilby, M.D.; Franklyn, J.; Coomarasamy, A. Association between thyroid autoantibodies and miscarriage and preterm birth: Meta-analysis of evidence. BMJ 2011, 342, d2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Ren, M.; Gao, Y.; Sun, K.; Wu, H.; Ding, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, D.; et al. Thyroid autoimmunity and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A multiple center retrospective study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1081851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphael, I.; Nalawade, S.; Eagar, T.N.; Forsthuber, T.G. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine 2014, 74, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinoer, D. The Regulation of Thyroid Function in Pregnancy: Pathways of Endocrine Adaptation from Physiology to Pathology. Endocr. Rev. 1997, 18, 404–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amino, N.; Ide, A. Maternal thyroid function and child IQ. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowden, T.C.; Schisterman, E.F.; Sjaarda, L.A.; Zarek, S.M.; Perkins, N.J.; Silver, R.; Galai, N.; DeCherney, A.H.; Mumford, S.L. Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Thyroid Autoimmunity Are Not Associated With Fecundity, Pregnancy Loss, or Live Birth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamja, R.; M, Y.; Patel, M.; Vala, V.; Ramachandran, A.; Surati, B.; Nagda, J. Impact of maternal thyroid dysfunction on fetal and maternal outcomes in pregnancy: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, K. Thyroid autoimmunity and hypothyroidism before and during pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. Update 2003, 9, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartáková, J.; Potluková, E.; Rogalewicz, V.; Fait, T.; Schöndorfová, D.; Telička, Z.; Krátký, J.; Jiskra, J. Screening for autoimmune thyroid disorders after spontaneous abortion is cost-saving and it improves the subsequent pregnancy rate. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Country | Randomization | Sample Size | Maternal Age (Mean ± SD) | AITD Type | Thyroid Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Dijk et al. (2022) [19] | Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark | A: LT4-treated TPOAb+ B: Untreated TPOAb+ | Total: 187 A: 94 B: 93 | A: 34.9 ± 4.2 B: 33.7 ± 4.7 | TPOAb+ | Euthyroid |

| Riaz et al. (2022) [22] | Lahore | A: LT4-treated with SCH B: Untreated with SCH | Total: 186 A: 93 B: 93 | A: 27.18 ± 2.68 B: 27.38 ± 2 | NR | SCH |

| Leng et al. (2022) [23] | China | PRL group: RPL + SCH LT4 Control RPL + TPOAb+ LT4 Control Normal group: Normal + SCH LT4 Control Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 Control | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 131 Control = 136 RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 42 Control = 41 Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 112 Control = 115 Preterm delivery | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 29.52 ± 3.75 Control = 29.58 ± 3.51 RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 28.72 ± 3.74 Control = 29.64 ± 3.98 Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 28.62 ± 3.52 Control = 28.53 ± 3.64 Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 28.64 ± 3.02 Control = 28.40 ± 2.57 | TPOAb+ and/or SCH | SCH or euthyroid with TPOAb+ |

| Amiri et al. (2022) [24] | Iran | A: LT4-treated with SCH and TPOAb+ B: Untreated with SCH and TPOAb+ | Total: 2277 | 27.70 ± 4.99 | TPOAb+ | Euthyroid and SCH |

| Nazarpour et al. (2017) [25] | Iran | A: LT4-treated TPOAb+ B: Untreated TPOAb+ C: Euthyroid TPOAb− | Total: 1159 A: 65 B: 66 C: 1028 | A: 26.6 ± 5.82 B: 27.0 ± 4.67 C: 27.1 ± 5.17 | TPOAb+ | Euthyroid and SCH |

| Kim et al. (2011) [26] | South Korea | A: LT4-treated with SCH and TPOAb+ B: Untreated with SCH and TPOAb+ | Total: 64 A: 32 B: 32 TPOAb+ A: 26/32 B: 25/32 | A: 36.0 ± 2.4 B: 36.1 ± 2.2 | TPOAb+ (TGAb status also reported) | SCH |

| Negro et al. (2006) [20] | Italy | A: LT4-treated TPOAb+ B: Untreated TPOAb+ C: Euthyroid TPOAb− | Total: 984 A: 57 B: 58 C: 869 | A: 30 ± 5 B: 30 ± 6 C: 28 ± 5 | TPOAb+ | Euthyroid |

| Negro et al. (2005) [21] | Italy | A: LT4-treated infertile TPOAb+ B: Untreated infertile TPOAb+ C: Infertile TPOAb− | Total: 484 A: 36 B: 36 C: 412 | Total: 30.2 ± 4 A: 29.2 ± 4 B: 29.2 ± 4 C: 30.4 ± 5 | TPOAb+ | Euthyroid |

| Author, Year | Miscarriage N (%) | Stillbirth N (%) | Preterm Birth N (%) | Mortality/Live Birth N (%) | Ongoing Pregnancy N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Dijk et al. (2022) [19] | A: 16/69 (23) B: 24/73 (33) | NR | A: 4/69 (6%) B: 3/73 (4.1) | A: 47/94 (50) B: 45/93 (48.4) | A: 47/69 (68.1) B: 46/73 (63) |

| Riaz et al. (2022) [22] | A: 56 (60.2) B: 73 (78.5) | NR | NR | A: 37 (39.8) B:20 (21.5) | NR |

| Leng et al. (2022) [23] | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 28 (21.4) Control = 54 (39.7) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 3 (7.1) Control = 11 (26.8) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 24 (21.4) Control = 22 (19.1) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 4 (9.7) Control = 3 (5.7) | NR | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 11 (11.9) Control = 22 (35.3) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 3 (7.9) Control = 3 (10.7) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 2 (2.6) Control = 7 (9.9) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 2 (5.9) Control = 6 (17.1) | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 92 (70.2) Control = 64 (47.1) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 38 (90.5) Control = 28 (68.3) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 7 (69.6) Control = 71 (61.7) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 34 (82.9) Control = 35 (87.5) | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 11 (8.4) Control = 18 (13.2) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 1 (2.4) Control = 2 (4.9) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 10 (8.9) Control = 22 (19.1) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 3 (7.3) Control = 2 (5) |

| Amiri et al. (2022) [24] | 75 (3.3) | Stillbirth: 4 (0.22) | 118 (6.56) | NR | NR |

| Nazarpour et al. (2017) [25] | A: 2 (3.6) B: 2 (3.4) C: 40 (4.3) | A: 0 B: 0 C: 2 (0.2) | A: 4 (7.1) B: 14 (23.7) C: 53 (5.6) | NR | NR |

| Kim et al. (2011) [26] | A: 0/17 B: 4/12 (33.3) | NR | A: 0/17 B: 1/12 | A: 17/32 (53.1) B: 8/32 (25) | NR |

| Negro et al. (2006) [20] | A: 2 (3.5) B: 8 (13.8) C: 21 (2.4) | NR | A: 4 (7) B: 13 (22.4) C: 71 (8.2) | NR | NR |

| Negro et al. (2005) [21] | A: 8/24 (33) B: 11/21 (52) C: 82/318 (26) | NR | NR | A: 16/24 B: 10/21 (28) C: 236/318 | NR |

| Author, Year | Placental Abruption N (%) | GHTN N (%) | PE N (%) | GDM N (%) | SGA N (%) | PROM N (%) | Macrosomia N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leng et al. (2022) [23] | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 1 (0.7) Control = 1 (0.7) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 0 Control = 0 Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 0 Control = 1 (0.9) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 0 Control = 0 | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 6 (4.6) Control = 3 (2.2) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 0 Control = 2 (4.8) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 5 (4.5) Control = 3 (2.7) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 2 (4.9) Control = 4 (10) | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 0 Control = 0 RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 0 Control = 1 (2.4) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 1 (0.9) Control = 2 (1.7) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 0 Control = 0 | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 8 (6.1) Control = 1 (0.7) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 4 (9.5) Control = 1 (2.4) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 4 (3.6) Control = 7 (6.1) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 2 (4.9) Control = 3 (7.5) | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 8 (8.7) Control = 3 (4.7) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 3 (7.8) Control = 0 Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 1 (1.3) Control = 2 (2.8) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 2 (5.9) Control = 2 (5.7) | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 0 Control = 0 RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 1 (2.4) Control = 0 Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 6 (5.4) Control = 1 (0.9) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 0 Control = 2 (5) | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 0 Control = 3 (4.7) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 0 Control = 1 (3.6) Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 2 (2.6) Control = 7 (8.9) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 3 (8.8) Control = 1 (2.9) |

| Amiri et al. (2022) [24] | 15 (0.83) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nazarpour et al. (2017) [25] | A: 0 B: 0 C: 5 (0.5) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Negro et al. (2006) [20] | A: 0 B: 1 (1.7) C: 4 (0.5) | A: 5 (8.8) B: 7 (12) C: 63 (7.2) | A: 2 (3.5) B: 3 (5.2) C: 32 (3.7) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Author, Year | Neonatal Admission N (%) | Gestational Age Mean (SD) | Asphyxia Neonatorum Mean (SD) | Survival 28 Days of Neonatal Life N (%) | Neonatal Thyroid Function Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Dijk et al. (2022) [19] | NR | NR | NR | A: 47/69 (68.1) B: 45/73 (61.6) | NR |

| Leng et al. (2022) [23] | NR | NR | PRL group RPL + SCH: LT4 = 0 Control = 2 (3.1) RPL + TPOAb+: LT4 = 0 Control = 0 Normal group Normal + SCH LT4 = 0 Control = 1 (1.4) Normal + TPOAb+ LT4 = 0 Control = 1 (2.9) | NR | NR |

| Amiri et al. (2022) [24] | 147 (8.18) | GA at first week: 11.64 (4.18) GA at delivery: 39.01 (1.67) | NR | NR | Neonate FT41 1st trimester: 2.9 (2.5–3.5) 2nd trimester: 3.3 (2.8–4.0) 3rd trimester: 2.8 (2.4–3.3) |

| Nazarpour et al. (2017) [25] | A: 2 (3.6) B: 12 (20.7) C: 75 (8.0) | A: 39.3 (1.3) B: 38.4 (1.7) C: 39.4 (1.4) | NR | NR | Neonatal TSH A: 1.3 (0.45–1.9) B: 1.0 (0.43–1.9) C: 0.90 (0.40–1.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sayed, A.A.; Abdulaal, M.M.; Emam, E.M.; Daftardar, L.M.; Kurdi, R.E.; Alahmadi, Y.B.; Alharbi, M.M.; Aloufi, R.M. Effect of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238520

Sayed AA, Abdulaal MM, Emam EM, Daftardar LM, Kurdi RE, Alahmadi YB, Alharbi MM, Aloufi RM. Effect of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238520

Chicago/Turabian StyleSayed, Anwar A., Maryam Mohammed Abdulaal, Elaf Mohammed Emam, Laila Mohammed Daftardar, Razan Essam Kurdi, Yara Basim Alahmadi, Mayes Mohammed Alharbi, and Razna Moustafa Aloufi. 2025. "Effect of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238520

APA StyleSayed, A. A., Abdulaal, M. M., Emam, E. M., Daftardar, L. M., Kurdi, R. E., Alahmadi, Y. B., Alharbi, M. M., & Aloufi, R. M. (2025). Effect of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238520