Refractory Thrombectomy: Incidence and Related Factors in a Third-Level Stroke Treatment Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study and Patient Selection

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Intracranial hemorrhage on non-contrast CT (NCCT).

- Inaccessible distal arterial occlusions.

- Effective recanalization after IVT.

- Inability to revise the NCCT.

- Absence of intracranial occlusion.

2.3. Clinical Data and Collected Variables

- Technical difficulties (this category includes 3 subgroups):

- -

- Difficulties in reaching the point of occlusion (vascular tortuosity and difficulty in arterial access).

- -

- Target occlusion was reached but the operator was unable to pass the thrombus with the microwire/microcatheter. In these cases, no SR was deployed.

- -

- Target occlusion was reached and the SR was deployed but no reperfusion occurred after multiple retrievals (no clot retrieval or dislocation).

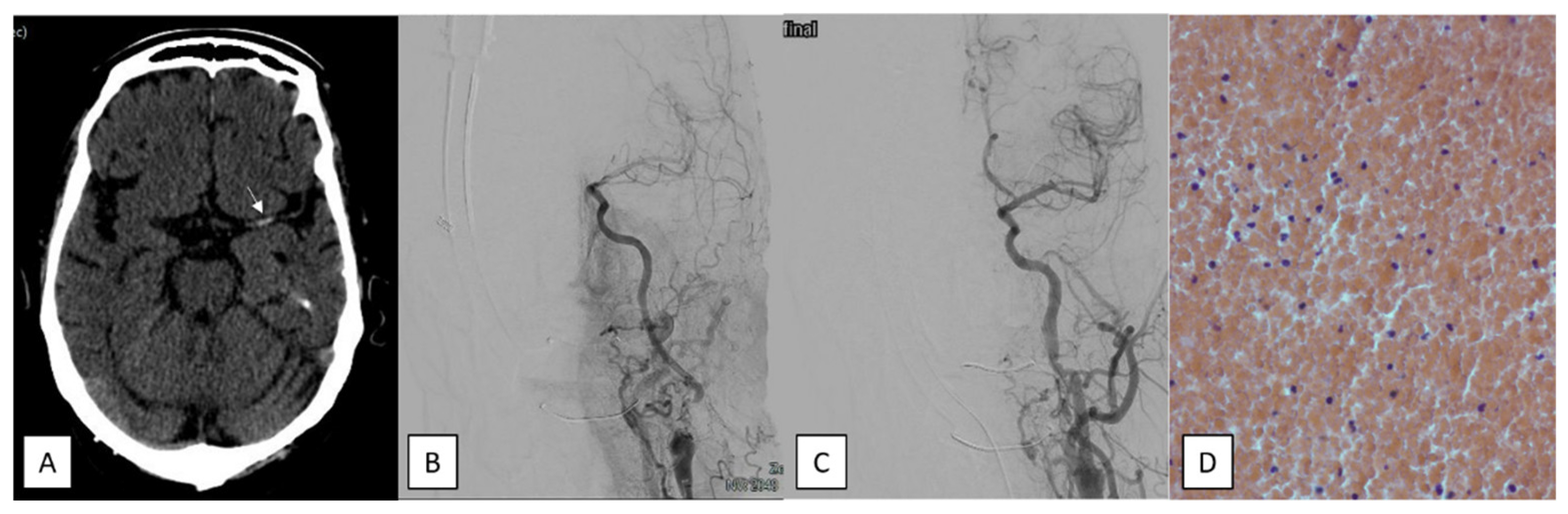

- Underlying intracranial stenosis. A severe (70–99%) residual stenosis and/or in situ thrombosis with reocclusion on repeat angiographies.

- Underlying intracranial dissection. The presence of a “double lumen” image; irregular segmental stenosis or “string sign”; fusiform or saccular dilatation (pseudoaneurysm); or a visible intimal flap (associated with compatible clinical signs) in the absence of other structural causes.

- Clot hardness/burden. A resistance to extraction despite correct device placement and the concomitant existence of a predominant fibrinoplatelet or calcium clot.

- Suboptimal devices. A poor adaptability to the consistency, size, or location of the thrombus. Poor apposition to the clot in stent retriever (SR), or an ineffective CA with suction catheters.

- Severe intraprocedural complications. This category includes hemodynamic complications, early hemorrhagic transformation, vessel perforation, distal embolization, and iatrogenic dissection.

3. Neuroimaging Protocol

4. Endovascular Procedure

5. Timeline of Technical and Technological Evolution

6. Histopathological and Bacteriological Analysis

- Red, fibrine, and mixed clots: A red clot occurs when the percentage of red blood cells is ≥60%. A fibrin-predominant clot is identified when the ratio of fibrin to platelet is ≥60%. A mixed clot is present if there is no clear predominance of these components.

- Septic clots: These occur when there is an increased number of white blood cells exhibiting morphological alterations. To detect bacteria, the slide was examined at 100× magnification (scale bar, 10 μm) using immersion oil.

- Calcium clots: a major component of calcified tissue.

- Fatty clots: an accumulation of adipose tissue as the major component.

7. Statistical Analysis

8. Ethical Approval

9. Results

10. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Acute ischemic stroke |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| ASPECTS | Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score |

| CGB | Balloon-guided catheter |

| CBV | Cerebral blood volume |

| CA | Contact aspiration |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| ET | Effective thrombectomy |

| EVT | Endovascular treatment |

| FPE | First pass effect |

| HBP | High blood pressure |

| HAS | Hyperdense artery sign |

| ICH | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| IVT | Intravenous thrombolysis |

| LVO | Large vessel occlusion |

| MT | Mechanical thrombectomy |

| MTT | Mean transit time |

| mRS | Modified Rankin scale |

| NCCT | Non-contrast computed tomography |

| PTA | Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty |

| RT | Refractory thrombectomy |

| SR | Stent retriever |

| TICA | Terminal carotid artery |

| TICI | Thrombolysis in cerebral infarction scale |

References

- Morales-Caba, L.; Puig, J.; Sanchís, J.M.; Vázquez, V.; Werner, M.; Dolz, G.; Comas-Cufí, M.; Daunis-I-Estadella, P.; Vega, P.; Murias, E.; et al. Mechanical thrombectomy failure in anterior circulation large vessel occlusion: An overview from the ROSSETTI registry. J. NeuroIntervent Surg. 2025, jnis-2025-023078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, R.N.; Cantrell, D.R.; Shaibani, A.; Hurley, M.; Jahromi, B.; Potts, M.; Ansari, S. Refractory Stroke Thrombectomy: Prevalence, Etiology, and Adjunctive Treatment in a North American Cohort. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Tanemura, H.; Ishigaki, T.; Miya, F. Predictors of Futile Recanalization after Mechanical Thrombectomy for Embolism-Related Large Vessel Occlusion in the Anterior Circulation. J. Neuroendovascular Ther. 2025, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverne, F.J.A.M.; Lima, F.O.; Rocha, F.D.A.; de Lucena, A.F.; Silva, H.C.; Lee, J.S.; Nogueira, R.G. Unfavorable Vascular Anatomy during Endovascular Treatment of Stroke: Challenges and Bailout Strategies. J. Stroke 2020, 22, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H.I.; Hong, J.M.; Lee, K.S.; Han, M.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, J.S.; Demchuk, A.M.; Lee, J.S. Imaging Predictors for Atherosclerosis-Related Intracranial Large Artery Occlusions in Acute Anterior Circulation Stroke. J. Stroke 2016, 18, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.E.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, B.; Heo, T.; Baek, B.; Lee, Y.; Yim, N. Incidence and Clinical Significance of Acute Reocclusion after Emergent Angioplasty or Stenting for Underlying Intracranial Stenosis in Patients with Acute Stroke. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2016, 37, 1690–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Lee, D.H.; Sung, J.H.; Song, S.Y. Analysis of failed mechanical thrombectomy with a focus on technical rea-sons: Ten years of experience in a single institution. J. Cerebrovasc. Endovasc. Neurosurg. 2023, 25, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Fernández, F.; Rojas-Bartolomé, L.; García-García, J.; Ayo-Martín, Ó.; Molina-Nuevo, J.D.; Barbella-Aponte, R.A.; Serrano-Heras, G.; Juliá-Molla, E.; Pedrosa-Jiménez, M.J.; Segura, T. Histopathological and Bacteriological Analysis of Thrombus Material Extracted During Mechanical Thrombectomy in Acute Stroke Patients. Cardiovasc. Intervent Radiol. 2017, 40, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joundi, R.A.; Menon, B.K. Thrombus Composition, Imaging, and Outcome Prediction in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurology 2021, 97, S68–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaesmacher, J.; Gralla, J.; Mosimann, P.J.; Zibold, F.; Heldner, M.; Piechowiak, E.; Dobrocky, T.; Arnold, M.; Fischer, U.; Mordasini, P. Reasons for Reperfusion Failures in Stent-Retriever-Based Thrombectomy: Registry Analysis and Proposal of a Classification System. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marnat, G.; Gory, B.; Sibon, I.; Kyheng, M.; Labreuche, J.; Boulouis, G.; Liegey, J.S.; Caroff, J.; Eugène, F.; Naggara, O.; et al. Mechanical thrombectomy failure in anterior circulation strokes: Outcomes and predictors of favorable outcome. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 2701–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, D.A.; Desai, S.M.; Perez, J.; Casillo, S.; Gross, B.A.; Jadhav, A.P. Predictors of first pass effect and effect on out-comes in mechanical thrombectomy for basilar artery occlusion. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 102, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniep, H.; Meyer, L.; Broocks, G.; Bechstein, M.; Heitkamp, C.; Winkelmeier, L.; Faizy, T.; Brekenfeld, C.; Flottmann, F.; Deb-Chatterji, M.; et al. Thrombectomy for M2 Occlusions: Predictors of Successful and Futile Recanalization. Stroke 2023, 54, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.P.; Bendixen, B.H.; Kappelle, L.J.; Biller, J.; Love, B.B.; Gordon, D.L.; Marsh, E.E. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treat-ment. Stroke 1993, 24, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Fernández, F.; Ramos-Araque, M.E.; Barbella-Aponte, R.; Molina-Nuevo, J.D.; García-García, J.; Ayo-Martin, O.; Pedrosa-Jiménez, M.J.; López-Martinez, L.; Serrano-Heras, G.; Julia-Molla, E.; et al. Fibrin-Platelet Clots in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Predictors and Clinical Significance in a Mechanical Thrombectomy Series. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 631343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; Van Zwam, W.H.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Mitchell, P.J.; Demchuk, A.M.; Dávalos, A.; Majoie, C.B.L.M.; Van Der Lugt, A.; De Miquel, M.A.; et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehnen, N.C.; Paech, D.; Zülow, S.; Bode, F.J.; Petzold, G.C.; Radbruch, A.; Dorn, F. First Experience with the Nimbus Sten-tretriever: A Novel Device to Handle Fibrin-rich Clots. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2023, 33, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staessens, S.; François, O.; Brinjikji, W.; Doyle, K.M.; Vanacker, P.; Andersson, T.; De Meyer, S.F. Studying Stroke Thrombus Composition After Thrombectomy: What Can We Learn? Stroke 2021, 52, 3718–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyer, S.F.; Andersson, T.; Baxter, B.; Bendszus, M.; Brouwer, P.; Brinjikji, W.; Campbell, B.C.; Costalat, V.; Dávalos, A.; Demchuk, A.; et al. Analyses of thrombi in acute ischemic stroke: A consensus statement on current knowledge and future directions. Int. J. Stroke 2017, 12, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Cortiñas, I.; Villanova, H.; Rios, A.; Galve, I.; Andersson, T.; Nogueira, R.; Jovin, T.; Ribo, M. ANCD thrombectomy device: In vitro evaluation. J. NeuroIntervent Surg. 2020, 12, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Funatsu, N.; Yamagami, H.; Satow, T.; Takahashi, J.C.; Nagatsuka, K.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Kira, J.-I.; Toyoda, K. Histopathologic Analysis of Retrieved Thrombi Associated With Successful Reperfusion After Acute Stroke Thrombectomy. Stroke 2016, 47, 3035–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.; McCarthy, R.; Farrell, M.; Thomas, S.; Brennan, P.; Power, S.; O’Hare, A.; Morris, L.; Rainsford, E.; MacCarthy, E.; et al. Per-Pass Analysis of Thrombus Composition in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy. Stroke 2019, 50, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, K.; Shibata, M.; Nakajima, H.; Thomas, S.; Brennan, P.; Power, S.; O’hare, A.; Morris, L.; Rainsford, E.; MacCarthy, E.; et al. Erythrocyte-Rich Thrombus Is Associated with Reduced Number of Maneuvers and Procedure Time in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra 2018, 8, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Bartolomé, L.; Payá, M.; Barbella-Aponte, R.; Carvajal, L.R.; García-García, J.; Ayo-Martín, O.; Molina-Nuevo, J.; Serrano-Heras, G.; Juliá-Molla, E.; Pedrosa-Jiménez, M.; et al. Histopathological composition of thrombus material in a large cohort of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A study of atypical clots. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1563371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebeskind, D.S.; Sanossian, N.; Yong, W.H.; Starkman, S.; Tsang, M.P.; Moya, A.L.; Zheng, D.D.; Abolian, A.M.; Kim, D.; Ali, L.K.; et al. CT and MRI Early Vessel Signs Reflect Clot Composition in Acute Stroke. Stroke 2011, 42, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, K.H.; Chang, F.C.; Lai, Y.J.; Pan, Y.-J. Hyperdense Artery Sign, Clot Characteristics, and Response to Intravenous Thrombolysis in Han Chinese People with Acute Large Arterial Infarction. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 25, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruggeman, A.A.E.; Aberson, N.; Kappelhof, M.; Dutra, B.G.; Hoving, J.W.; Brouwer, J.; Tolhuisen, M.L.; Terreros, N.A.; Konduri, P.R.; Boodt, N.; et al. Association of thrombus density and endovascular treatment outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to M1 occlusions. Neuroradiology 2022, 64, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, D.; Jia, B.; Huo, X.; Tong, X.; Wang, A.; Ma, N.; Gao, F.; Mo, D.; Miao, Z.; et al. Hyperdense Middle Cerebral Artery Sign as a Predictor of First-Pass Recanalization and Favorable Outcomes in Direct Thrombectomy Patients. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2024, 35, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.G.; Andersson, T.; Haussen, D.C.; Yoo, A.J.; Hanel, R.A.; Zaidat, O.O.; Hacke, W.; Jovin, T.G.; Fiehler, J.; De Meyer, S.F.; et al. EXCELLENT Registry: A Prospective, Multicenter, Global Registry of Endovascular Stroke Treatment With the EMBOTRAP Device. Stroke 2024, 55, 2804–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Hong, J.M.; Alverne, F.J.A.M.; Lima, F.O.; Nogueira, R.G. Endovascular Treatment of Large Vessel Occlusion Strokes Due to Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease. J. Stroke 2022, 24, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajthia, O.; Almallouhi, E.; Ali, H.; Essibayi, M.A.; Bass, E.; Neyens, R.; Anadani, M.; Chalhoub, R.; Kicielinski, K.; Lena, J.; et al. Failed mechanical thrombectomy: Prevalence, etiology, and predictors. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 139, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K.; Yamagami, H.; Sakai, N.; Shirakawa, M.; Beppu, M.; Toyoda, K.; Matsumaru, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Todo, K.; Hayakawa, M.; et al. Endovascular therapy for acute intracranial large vessel occlusion due to atherothrombosis: Multicenter historical registry. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2024, 16, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Ming, B.; Yang, D.; Qiao, H.; Xu, N.; Shen, R.; Han, Y.; Zhao, X. Diabetes-specific characteristics of intracranial artery atherosclerosis: A magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2025, 141, 111585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.A.; Spring, K.J.; Beran, R.G.; Chatzis, D.; Killingsworth, M.C.; Bhaskar, S.M.M. Role of diabetes in stroke: Recent advances in pathophysiology and clinical management. Diabetes Metab. Res. 2022, 38, e3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, O.R.; Santos, A.B.; Hong, A.; Brandão, M.F.H.; Monteiro, G.d.A.; da Silva, L.R.; Júnior, A.B.d.S.; Simoni, G.H.; de Aquino, K.I.F.; Filho, P.B.P.B.; et al. Endovascular thrombectomy versus standard medical treatment in acute ischemic stroke patients with large infarcts (ASPECTS 5): A meta-analysis. Neuroradiol. J. 2025, 22, 19714009251345105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, A.H.; Sarraj, A.; Froheler, M.; Purrucker, J.; Goyal, N.; Regenhardt, R.W.; Palaiodimou, L.; Mueller-Kronast, N.H.; Lemmens, R.; Schellinger, P.D.; et al. IV Thrombolysis Initiated Before Transfer for Endovascular Stroke Thrombectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurology 2023, 100, e1436–e1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.S.; Loh, Y.; Walker, G.; Duckwiler, G.R.; for the MERCI and Multi-MERCI Investigators. Clinical outcomes in middle cerebral artery trunk occlusions versus secondary division occlusions after mechanical thrombectomy: Pooled analysis of the Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia (MERCI) and Multi MERCI trials. Stroke 2010, 41, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ET N = 679 (92.6%) | RT N = 54 (7.4%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and Comorbidities | |||

| Age, Mean Years (±SD) | 70.2 (12.7) | 71.8 (11.2) | 0.3 |

| Sex Female, N (%) | 295 (43.4) | 22 (40.7) | 0.77 |

| HBP, N (%) | 464 (68.3) | 38 (70.4) | 0.88 |

| DM, N (%) | 185 (27.2) | 22 (40.7) | 0.04 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, N (%) | 282 (41.5) | 23 (42.6) | 0.89 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease, N (%) | 77 (11.3) | 8 (14.8) | 0.5 |

| Intermittent Claudication N (%) | 22 (3.2) | 2 (3.7) | 0.91 |

| AF, N (%) | 273 (40.4) | 19 (35.2) | 0.47 |

| Anticoagulation, N (%) | 164 (24.2) | 37 (68.5) | 0.15 |

| Laboratory Findings | |||

| Glycemia, Mean gr/dL (±SD) | 138.9 (53.2) | 142.5 (52.2) | 0.6 |

| Leukocytes, Mean/μL (±SD) | 9576 (3312.4) | 10,946 (6637.9) | 0.14 |

| Fibrinogen, Mean mg/dL (±SD) | 361.85 (86.3) | 364.35 (85.2) | 0.84 |

| Hematocrit, Mean (%) | 41.9 | 40.6 | 0.11 |

| Stroke Characteristics | |||

| Baseline NIHSS, Median (IQR) | 17 (11–23) | 16.5 (11–22) | 0.85 |

| Territory occluded, N (%) | |||

| M1 | 272 (37.1) | 14 (25.9) | 0.026 |

| M2 | 101 (14.9) | 7 (13) | 0.44 |

| TICA | 73 (10.8) | 7 (13) | 0.37 |

| Carotid tandem | 112 (16.5) | 8 (14.8) | 0.47 |

| ACA | 4 (0.6) | 3 (5.6) | 0.011 |

| Basilar | 46 (6.8) | 5 (9.3) | 0.32 |

| PCA | 18 (2.7) | 6 (11.1) | 0.006 |

| HAS, N (%) | 404 (59.5) | 17 (31.5) | 0.0001 |

| ASPECTS score, Median (IQR) | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–10) | 0.33 |

| Mismatch, Average Ratio (±DE) | 82 (20.2) | 85.3 (15.4) | 0.23 |

| IV Thrombolysis, N (%) | 219 (32.3) | 11 (20.4) | 0.09 |

| Uncertain time evolution | 195 (28.7) | 11 (20.4) | 0.21 |

| Median Time from Symptom Onset to Groin Puncture, Minutes (IQR) | 295 (201–577) | 283 (226.5–465) | 0.99 |

| Local anesthesia, N (%) | 7 (13) | 39 (5.7) | 0.071 |

| First-line strategy, N (%) | |||

| SR | 523 (80.8) | 26 (65) | 0.02 |

| CA | 102 (15.8) | 14 (35) | 0.004 |

| Combined technique | 22 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 0.63 |

| Intracranial PTA/stenting rescue | 26 (3.8) | 8 (14.8) | 0.002 |

| Atherothrombotic Cause, N (%) | 134 (19.7) | 21 (38.9) | 0.003 |

| Cardioembolic Cause, N (%) | 351 (51.7) | 19 (35.2) | 0.02 |

| Intracranial Stenosis, N (%) | 47 (6.9) | 7 (13) | 0.11 |

| Histopathological analysis | |||

| Red clot, N (%) | 148 (26.5) | 1 (5) | 0.0001 |

| Fibrin clot, N (%) | 263 (47) | 8 (40) | 0.65 |

| Mixed clot, N (%) | 124 (22.2) | 7 (35) | 0.18 |

| Septic clot, N (%) | 16 (2.9) | 1 (5) | 0.45 |

| Calcium clot, N (%) | 6 (1.1) | 2 (10) | 0.03 |

| Fatty clot, N (%) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (5) | 0.1 |

| Outcome Variables | |||

| Favorable mRS at 3 Months, N (%) | 407 (59.9) | 5 (9.3) | 0.0001 |

| sICH, N (%) | 24 (3.5) | 7 (13) | 0.005 |

| Mortality, N (%) | 91 (13.4) | 22 (40.7) | 0.0001 |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Difficulties | 18 | 33.3 |

| Underlying Intracranial Stenosis | 7 | 13 |

| Thrombus Hardness/Burden (Recalcitrant Clot) | 17 | 31.5 |

| Suboptimal Devices | 4 | 7.4 |

| Severe Intraprocedural Complication | 8 | 14.8 |

| Intracranial Dissections | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 54 | 100 |

| Variables | Outcomes | OR | 95% CI for OR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | ||||

| Age | RT | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.03 | 0.44 |

| sICH | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.31 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.01 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 0.09 | |

| M1 occlusion | RT | 0.47 | 0.15 | 1.5 | 0.20 |

| sICH | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.03 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 1.24 | 035 | |

| ACA occlusion | RT | 59,111 | 0 | - | 1 |

| sICH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.99 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.99 | |

| ACP occlusion | RT | 0.11 | 0.006 | 1.4 | 0.09 |

| sICH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.99 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 0.28 | 0.74 | 11.01 | 0.13 | |

| NIHSS | RT | 0.95 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.15 |

| sICH | 1.1 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 0.008 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 0.0001 | |

| DM | RT | 1.11 | 0.39 | 3.2 | 0.84 |

| sICH | 0.53 | 0.21 | 1.32 | 0.17 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 0.004 | |

| IVT | RT | 0.57 | 0.18 | 1.94 | 0.58 |

| sICH | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 0.03 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.06 | 0.72 | 1.58 | 0.75 | |

| Local anesthesia | RT | 0.24 | 0.05 | 1.11 | 0.07 |

| sICH | 1.24 | 0.14 | 11.36 | 0.85 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.48 | 0.6 | 3.66 | 0.4 | |

| SR as first-line | RT | 15,328 | 0 | - | 1 |

| sICH | 0.8 | 0.09 | 6.9 | 0.84 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 2.78 | 0.92 | |

| CA as first-line | RT | 1693 | 0 | - | 1 |

| sICH | 2.53 | 0.2 | 32.63 | 0.48 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.31 | 0.45 | 3.8 | 0.62 | |

| Red clot | RT | 0.19 | 0.02 | 1.52 | 0.12 |

| sICH | 1.41 | 0.48 | 4.11 | 0.53 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.31 | 0.85 | 2.01 | 0.23 | |

| Calcium clot | RT | 0.7 | 0.01 | 5.03 | 0.72 |

| sICH | 2.2 | 0.19 | 25.17 | 0.52 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.27 | 0.26 | 6.22 | 0.76 | |

| Atherothrombotic Cause | RT | 4.22 | 1.10 | 16.25 | 0.04 |

| sICH | 0.46 | 0.13 | 1.6 | 0.22 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 1.51 | 0.56 | |

| Cardioembolic Cause | RT | 0.43 | 0.11 | 1.64 | 0.22 |

| sICH | 0.92 | 0.3 | 2.83 | 0.88 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.07 | 0.68 | 1.67 | 0.77 | |

| HAS | RT | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.02 |

| sICH | 1.55 | 0.21 | 1.32 | 0.36 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 1.37 | 0.91 | 2.05 | 0.13 | |

| RT | RT | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| sICH | 0.44 | 0.08 | 2.44 | 0.35 | |

| mRS 0-2 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.001 | |

| Red | Fibrin | Mixed | Septic | Fatty | Calcium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | p | N (%) | p | N (%) | p | N (%) | p | N (%) | p | N (%) | p | |

| First-line strategy: SR | 118 (79.2) | 0.39 | 222 (81.9) | 0.91 | 112 (85.5) | 0.25 | 12 (75) | 0.51 | 1 (33.3) | 0.09 | 7 (87.5) | 1 |

| First-line strategy: CA | 24 (16.1) | 0.69 | 42 (15.5) | 0.72 | 14 (16.7) | 0.16 | 3 (18.8) | 0.71 | 2 (66.7) | 0.059 | 1 (12.5) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Restrepo-Carvajal, L.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; Fernández-López, A.; Rojas-Bartolomé, L.; de la Fuente, M.; Alcahut, C.; Serrano-Serrano, B.; Payá, M.; Molina-Nuevo, J.D.; García-García, J.; et al. Refractory Thrombectomy: Incidence and Related Factors in a Third-Level Stroke Treatment Center. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238514

Restrepo-Carvajal L, Hernández-Fernández F, Fernández-López A, Rojas-Bartolomé L, de la Fuente M, Alcahut C, Serrano-Serrano B, Payá M, Molina-Nuevo JD, García-García J, et al. Refractory Thrombectomy: Incidence and Related Factors in a Third-Level Stroke Treatment Center. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238514

Chicago/Turabian StyleRestrepo-Carvajal, Laura, Francisco Hernández-Fernández, Angela Fernández-López, Laura Rojas-Bartolomé, Miguel de la Fuente, Cristian Alcahut, Blanca Serrano-Serrano, María Payá, Juan David Molina-Nuevo, Jorge García-García, and et al. 2025. "Refractory Thrombectomy: Incidence and Related Factors in a Third-Level Stroke Treatment Center" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238514

APA StyleRestrepo-Carvajal, L., Hernández-Fernández, F., Fernández-López, A., Rojas-Bartolomé, L., de la Fuente, M., Alcahut, C., Serrano-Serrano, B., Payá, M., Molina-Nuevo, J. D., García-García, J., Ayo-Martín, O., Barbella-Aponte, R. A., Serrano-Heras, G., & Segura, T. (2025). Refractory Thrombectomy: Incidence and Related Factors in a Third-Level Stroke Treatment Center. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238514