Artificial Intelligence Enabled Lung Sound Auscultation in the Early Diagnosis and Subtyping of Interstitial Lung Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Evolution of ILD Diagnosis

1.2. Auscultation in ILD: A Missed Opportunity

1.3. Bridging to AI: A Promising Solution

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

2.2. Literature Search

2.3. Eligibility and Data Synthesis

3. Pathophysiology of Lung Sound Production in ILD

3.1. Mechanism of Lung Sound Production in ILD

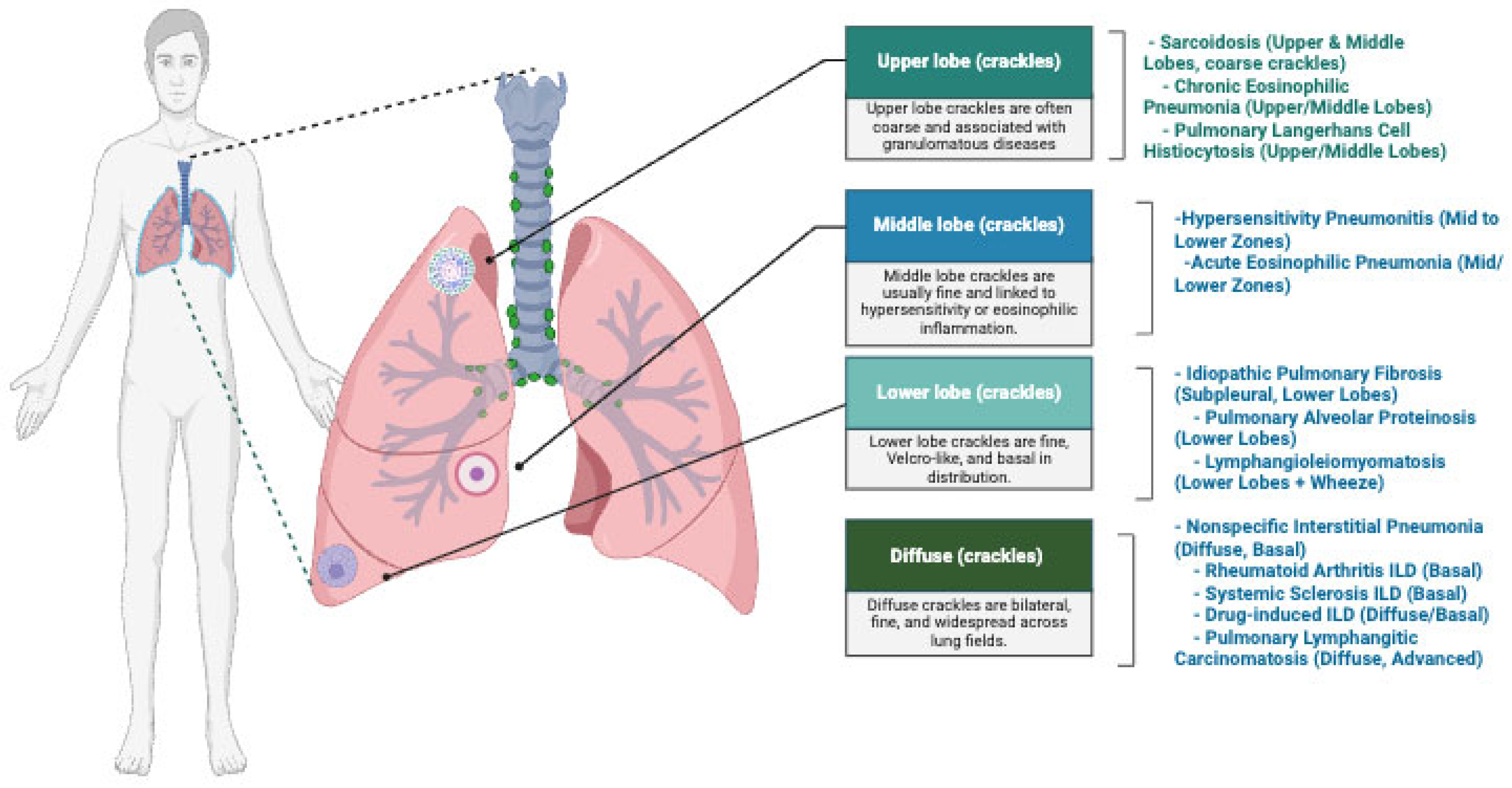

3.2. Clinical Implications of the Auscultatory Findings

4. AI Techniques in ILD: Detection and Processing of Lung Sounds and Imaging

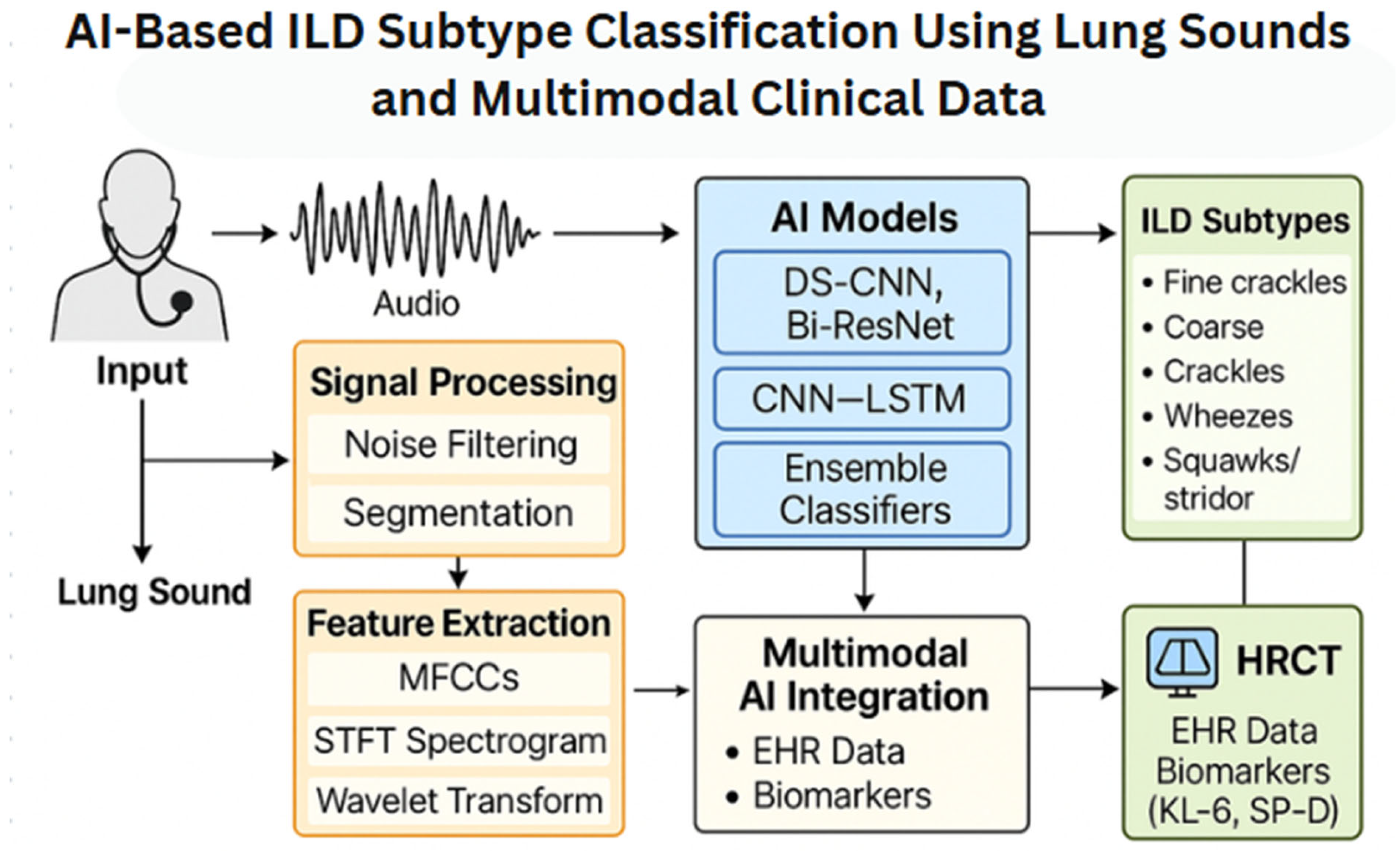

4.1. AI in Lung Sound Analysis

4.2. AI Beyond Lung Sounds: Toward Multimodal Early ILD Detection

5. Current Diagnostic Modalities for ILD

6. Discussion

6.1. AI in General Medicine

6.2. Challenges in ILD Diagnosis

6.3. Limitations of the Current Diagnostic Paradigms

6.4. Auscultation: An Underrecognized Tool in ILD Diagnosis

6.5. AI in Established ILD Modalities

6.6. The Potential of AI-Enhanced Auscultation

6.7. Real-World Deployment and Clinical Trial Evidence

6.8. Advantages of AI-Based Auscultation

6.9. Comparative Advantages over Traditional and Emerging Diagnostic Modalities

6.10. Clinical Effectiveness: Evidence from Trials and Real-World Validation

6.11. Addressing Global Equity and Accessibility Gaps

6.12. Global Health Access and Deployment Strategies

- Partnerships with local health authorities.

- Language-agnostic algorithm development.

- Robust community engagement strategies.

6.13. The Future of ILD Stratification Through Auscultatory Signatures

6.14. Integration with High-Risk Screening Protocols

6.15. Interoperability and Health System Integration

6.16. Innovations in Machine Learning for Pulmonary AI

7. Future Directions

7.1. Multimodal Integration: The Future of AI in ILD Diagnosis

7.2. Fairness Metrics: Ensuring Equity in AI-Auscultation

7.3. Policy Recommendations: National AI-Health Initiatives

7.4. Patient Trust and Transparency: Building Confidence

7.5. Barriers to AI-Auscultation Adoption

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crystal, R.G.; Gadek, J.E.; Ferrans, V.J.; Fulmer, J.D.; Line, B.R.; Hunninghake, G.W. Interstitial lung disease: Current concepts of pathogenesis, staging and therapy. Am. J. Med. 1981, 70, 542–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhu, L.; Kurche, J.S.; Xiao, H.; Dai, H.; Wang, C. Global and regional burden of interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Thorax 2022, 77, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, H.R.; Tino, G.; Noble, P.W.; Shreve, M.A.; Michaels, M.; Carlson, B.; Schwarz, M.I. Patient experiences with pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamas, D.J.; Kawut, S.M.; Bagiella, E.; Philip, N.; Arcasoy, S.M.; Lederer, D.J. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A cohort study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pritchard, D.; Adegunsoye, A.; Lafond, E.; Pugashetti, J.V.; DiGeronimo, R.; Boctor, N.; Sarma, N.; Pan, I.; Strek, M.; Kadoch, M.; et al. Diagnostic test interpretation and referral delay in patients with interstitial lung disease. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ose, B.; Sattar, Z.; Gupta, A.; Toquica, C.; Harvey, C.; Noheria, A. Artificial Intelligence Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram: A State-of-the-Art Review. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siontis, K.C.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Attia, Z.I.; Friedman, P.A. Artificial intelligence-enhanced electrocardiography in cardiovascular disease management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Najjar, R. Redefining Radiology: A Review of Artificial Intelligence Integration in Medical Imaging. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bera, K.; Schalper, K.A.; Rimm, D.L.; Velcheti, V.; Madabhushi, A. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology—New tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, M.; Li, M.; Guo, L.; Liu, J. A Low-Cost AI-Empowered Stethoscope and a Lightweight Model for Detecting Cardiac and Respiratory Diseases from Lung and Heart Auscultation Sounds. Sensors 2023, 23, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, D.M.; Huang, J.; Qiao, K.; Zhong, N.S.; Lu, H.Z.; Wang, W.J. Deep learning-based lung sound analysis for intelligent stethoscope. Mil. Med. Res. 2023, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pancaldi, F.; Sebastiani, M.; Cassone, G.; Luppi, F.; Cerri, S.; Della Casa, G.; Manfredi, A. Analysis of pulmonary sounds for the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 96, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiery, J.P.; Sleeman, J.P. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koli, K.; Myllärniemi, M.; Keski-Oja, J.; Kinnula, V.L. Transforming growth factor-beta activation in the lung: Focus on fibrosis and reactive oxygen species. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredberg, J.J.; Holford, S.K. Discrete lung sounds: Crackles (rales) as stress-relaxation quadrupoles. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1983, 73, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyshedskiy, A.; Bezares, F.; Paciej, R.; Ebril, M.; Shane, J.; Murphy, R. Transmission of crackles in patients with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia. Chest 2005, 128, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellarés, J.; Hernández-González, F.; Lucena, C.M.; Paradela, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Prieto-González, S.; Benegas, M.; Cuerpo, S.; Espinosa, G.; Ramírez, J.; et al. Auscultation of Velcro Crackles is Associated With Usual Interstitial Pneumonia. Medicine 2016, 95, e2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frazer, D.G.; Franz, G.N. Trapped gas and lung hysteresis. Respir. Physiol. 1981, 46, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walshaw, M.J.; Nisar, M.; Pearson, M.G.; Calverley, P.M.; Earis, J.E. Expiratory lung crackles in patients with fibrosing alveolitis. Chest 1990, 97, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Román, F.; Valenzuela, C.; Molina-Molina, M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Med. Clin. 2022, 159, 189–194, (In English, Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuillet, S.; Tazi, A. Les pneumopathies infiltrantes aiguës: Démarche diagnostique et approche thérapeutique [Acute interstitial pneumonia: Diagnostic approach and management]. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires 2011, 28, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Travis, W.; Lynch, J.P., 3rd. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 22, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazelaar, H.D.; Wright, J.L.; Churg, A. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Histopathology 2011, 58, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.; Maini, R.; Hershberger, D.M. Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia. 2022 Sep 12. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wells, A.U.; Nicholson, A.G.; Hansell, D.M.; du Bois, R.M. Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 24, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.I.; Fessler, M.B.; Cool, C.D.; Schwarz, M.I.; Brown, K.K. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia: Clinical features, associations and prognosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 28, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, D.I.; Ascherman, D.P. Rheumatoid Arthritis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (RA-ILD): Update on Prevalence, Risk Factors, Pathogenesis, and Therapy. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2024, 26, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perelas, A.; Silver, R.M.; Arrossi, A.V.; Highland, K.B. Systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saketkoo, L.A.; Ascherman, D.P.; Cottin, V.; Christopher-Stine, L.; Danoff, S.K.; Oddis, C.V. Interstitial Lung Disease in Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathy. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2010, 6, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moda, M.; Yanagihara, T.; Nakashima, R.; Sumikawa, H.; Shimizu, S.; Arai, T.; Inoue, Y. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease in Adults. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2025, 88, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chandra, D.; Cherian, S.V. Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, J.; Thada, P.K.; Sedhai, Y.R. Asbestosis. 2022 Sep 19. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnes, H.; Goh, N.S.L.; Leong, T.L.; Hoy, R. Silica-associated lung disease: An old-world exposure in modern industries. Respirology 2019, 24, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon-Calderon, A.; Vassallo, R.; Yi, E.S.; Ryu, J.H. Smoking-Related Interstitial Lung Diseases. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2023, 43, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Bonniaud, P.; Rossi, G.; Sverzellati, N.; Cottin, V. Drug-induced interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Hernández, M.; Maldonado, F.; Lozano-Ruiz, F.; Muñoz-Montaño, W.; Nuñez-Baez, M.; Arrieta, O. Radiation-induced lung injury: Current evidence. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, S.R.; Cordier, J.F.; Lazor, R.; Cottin, V.; Costabel, U.; Harari, S.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; Boehler, A.; Brauner, M.; Popper, H.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 35, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathirareuangchai, S.; Shimizu, D.; Vierkoetter, K.R. Pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2020, 79, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Mahony, A.M.; Lynn, E.; Murphy, D.J.; Fabre, A.; McCarthy, C. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: A clinical review. Breathe 2020, 16, 200007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delobbe, A.; Durieu, J.; Duhamel, A.; Wallaert, B. Determinants of survival in pulmonary Langerhans’ cell granulomatosis (histiocytosis X). Groupe d’Etude en Pathologie Interstitielle de la Société de Pathologie Thoracique du Nord. Eur. Respir. J. 1996, 9, 2002–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassallo, R.; Ryu, J.H.; Schroeder, D.R.; Decker, P.A.; Limper, A.H. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basset, F.; Corrin, B.; Spencer, H.; Lacronique, J.; Roth, C.; Soler, P.; Battesti, J.P.; Georges, R.; Chrétien, J. Pulmonary histiocytosis X. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1978, 118, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Juvet, S.C.; Hwang, D.; Downey, G.P. Rare lung diseases III: Pulmonary Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Can. Respir. J. 2010, 17, e55–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trapnell, B.C.; Nakata, K.; Bonella, F.; Campo, I.; Griese, M.; Hamilton, J.; Wang, T.; Morgan, C.; Cottin, V.; McCarthy, C. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łyżwa, E.; Wakuliński, J.; Szturmowicz, M.; Tomkowski, W.; Sobiecka, M. Fibrotic Pulmonary Sarcoidosis-From Pathogenesis to Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lederer, D.J.; Martinez, F.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giacomi, F.; Vassallo, R.; Yi, E.S.; Ryu, J.H. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia. Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, M.; Robinson, D.; Sagar, M.; Chen, L.; Ghamande, S. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: Clinical perspectives. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katoh, S.; Ikeda, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Shimizu, H.; Abe, M.; Ohue, Y.; Mouri, K.; Kobashi, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Oka, M. Possible Role of IL-25 in Eosinophilic Lung Inflammation in Patients with Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia. Lung 2017, 195, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AKAK; Mantri, S.N. Lymphangitic Carcinomatosis. 2023 Jul 4. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klimek, M. Pulmonary lymphangitis carcinomatosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of case reports, 1970-2018. Postgrad Med. 2019, 131, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petmezas, G.; Cheimariotis, G.-A.; Stefanopoulos, L.; Rocha, B.; Paiva, R.P.; Katsaggelos, A.K.; Maglaveras, N. Automated Lung Sound Classification Using a Hybrid CNN-LSTM Network and Focal Loss Function. Sensors 2022, 22, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-Y.; Liao, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-S.; Yuan, S.-M.; Sun, C.-T. Efficiently Classifying Lung Sounds through Depthwise Separable CNN Models with Fused STFT and MFCC Features. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ye, N.; Jiang, J. Classification and Recognition of Lung Sounds Based on Improved Bi-ResNet Model. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 73079–73094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.; Daoud, M.I.; Al-Khassaweneh, M.; Bataineh, E.; Al-Dwairi, M. Automated classification of lung sounds using ensemble classifiers. Measurement 2020, 163, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Ke, S.; Mo, L.; Qiu, M.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, W.; Liu, L. Identifying potential biomarkers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through machine learning analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teramachi, R.; Furukawa, T.; Kondoh, Y.; Karasuyama, M.; Hozumi, H.; Kataoka, K.; Oyama, S.; Suda, T.; Shiratori, Y.; Ishii, M. Deep Learning for Predicting Acute Exacerbation and Mortality of Interstitial Lung Disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2025, 22, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beverin, L.; Topalovic, M.; Halilovic, A.; Desbordes, P.; Janssens, W.; De Vos, M. Predicting total lung capacity from spirometry: A machine learning approach. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1174631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lim, J.; Kim, N.; Seo, J.B.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, Y.; Kang, S.H. Regional context-sensitive support vector machine classifier to improve automated identification of regional patterns of diffuse interstitial lung disease. J. Digit. Imaging 2011, 24, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boros, P.W.; Franczuk, M.; Wesolowski, S. Value of spirometry in detecting volume restriction in interstitial lung disease patients. Spirometry in interstitial lung diseases. Respiration 2004, 71, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Naito, T.; Omae, K.; Omori, S.; Nakashima, K.; Wakuda, K.; Ono, A.; Kenmotsu, H.; Murakami, H.; Endo, M.; et al. ILD-NSCLC-GAP index scoring and staging system for patients with non-small cell lung cancer and interstitial lung disease. Lung Cancer 2018, 121, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, M.; Hara, Y.; Fujii, H.; Murohashi, K.; Saigusa, Y.; Zhao, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Nagasawa, R.; Tagami, Y.; Izawa, A.; et al. ILD-GAP combined with the monocyte ratio could be a better prognostic prediction model than ILD-GAP in patients with interstitial lung diseases. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thrainsson, L.; Halldorsson, Á.B.; Ingason, Á.B.; Isaksson, H.J.; Gudmundsson, G.; Gudbjartsson, T. Surgical lung biopsy for suspected interstitial lung disease with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is safe, providing exact histological and disease specific diagnosis for tailoring treatment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zanatta, E.; Martini, A.; Depascale, R.; Gamba, A.; Tonello, M.; Gatto, M.; Giraudo, C.; Balestro, E.; Doria, A.; Iaccarino, L. CCL18 as a Biomarker of Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) and Progressive Fibrosing ILD in Patients with Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Le Guen, P.; Iquille, J.; Debray, M.-P.; Guyard, A.; Roussel, A.; Borie, R.; Dombret, M.-C.; Dupin, C.; Ghanem, M.; Taille, C.; et al. Clinical Impact of Surgical Lung Biopsy for Interstitial Lung Disease in a Reference Center. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 114, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, G.; Gill, R.; Gagne, S.; Byrne, S.; Huang, W.; Cui, J.; Prisco, L.; Zaccardelli, A.; Martin, L.; Kronzer, V.L.; et al. Associations of the MUC5B promoter variant with timing of interstitial lung disease and rheumatoid arthritis onset. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 4915–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gui, X.; Shenyun, S.; Ding, H.; Wang, R.; Tong, J.; Yu, M.; Zhao, T.; Ma, M.; Ding, J.; Xin, X.; et al. Anti-Ro52 antibodies are associated with the prognosis of adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathy-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 4570–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, K.; Matsunaga, K.; Asami-Noyama, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Hisamoto, Y.; Fujii, T.; Harada, M.; Suizu, J.; Murakawa, K.; Chikumoto, A.; et al. The 1-minute sit-to-stand test to detect desaturation during 6-minute walk test in interstitial lung disease. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2022, 32, 5, Erratum in NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2022, 32, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-022-00274-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harari, S.; Wells, A.U.; Wuyts, W.A.; Nathan, S.D.; Kirchgaessler, K.U.; Bengus, M.; Behr, J. The 6-min walk test as a primary end-point in interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, J.H.; Pan, L.; Gao, Y.B.; Cui, G.H.; Wang, Y.H. Utility of lung ultrasound to identify interstitial lung disease: An observational study based on the STROBE guidelines. Medicine 2021, 100, e25217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matson, S.M.; Lee, S.J.; Peterson, R.A.; Achtar-Zadeh, N.A.; Boin, F.; Wolters, P.J.; Lee, J.S. The prognostic role of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, H.C.; Choi, K.H.; Jacob, J.; Song, J.W. Prognostic role of blood KL-6 in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pugashetti, J.V.; Kitich, A.; Alqalyoobi, S.; Maynard-Paquette, A.C.; Pritchard, D.; Graham, J.; Boctor, N.; Kulinich, A.; Lafond, E.; Foster, E.; et al. Derivation and Validation of a Diagnostic Prediction Tool for Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest 2020, 158, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Newton, C.A.; Oldham, J.M.; Ley, B.; Anand, V.; Adegunsoye, A.; Liu, G.; Batra, K.; Torrealba, J.; Kozlitina, J.; Glazer, C.; et al. Telomere length and genetic variant associations with interstitial lung disease progression and survival. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamakawa, H.; Hagiwara, E.; Kitamura, H.; Yamanaka, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Sekine, A.; Baba, T.; Okudela, K.; Iwasawa, T.; Takemura, T.; et al. Serum KL-6 and surfactant protein-D as monitoring and predictive markers of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis and mixed connective tissue disease. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kropski, J.A.; Young, L.R.; Cogan, J.D.; Mitchell, D.B.; Lancaster, L.H.; Worrell, J.A.; Markin, C.; Liu, N.; Mason, W.R.; Fingerlin, T.E.; et al. Genetic Evaluation and Testing of Patients and Families with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bauer, P.R.; Kalra, S.; Osborn, T.G.; St Sauver, J.; Hanson, A.C.; Schroeder, D.R.; Ryu, J.H. Influence of autoimmune biomarkers on interstitial lung diseases: A tertiary referral center based case-control study. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guo, Y.; Jin, Q.; Kang, Y.; Jin, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.G. Integrating machine learning and neural networks for new diagnostic approaches to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and immune infiltration research. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gompelmann, D.; Gysan, M.R.; Desbordes, P.; Maes, J.; Van Orshoven, K.; De Vos, M.; Steinwender, M.; Helfenstein, E.; Marginean, C.; Henzi, N.; et al. AI-powered evaluation of lung function for diagnosis of interstitial lung disease. Thorax 2025, 80, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiot, J.; Henket, M.; Gester, F.; André, B.; Ernst, B.; Frix, A.N.; Smeets, D.; Van Eyckhoven, S.; Antoniou, K.; Conemans, L.; et al. Automated AI-based image analysis for quantification and prediction of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis patients. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, Y.; Ma, S.F.; Oldham, J.M.; Adegunsoye, A.; Zhu, D.; Murray, S.; Kim, J.S.; Bonham, C.; Strickland, E.; Linderholm, A.L.; et al. Machine Learning of Plasma Proteomics Classifies Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Felder, F.N.; Walsh, S.L.F. Exploring computer-based imaging analysis in interstitial lung disease: Opportunities and challenges. ERJ Open Res. 2023, 9, 00145–02023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guerra, X.; Rennotte, S.; Fetita, C.; Boubaya, M.; Debray, M.P.; Israël-Biet, D.; Bernaudin, J.F.; Valeyre, D.; Cadranel, J.; Naccache, J.M.; et al. U-net convolutional neural network applied to progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease: Is progression at CT scan associated with a clinical outcome? Respir. Med. Res. 2024, 85, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sankar, R. Classification and Recognition of Lung Sounds Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: A Literature Review. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Ivorra, J.A.; Trallero-Araguas, E.; Lopez Lasanta, M.; Cebrián, L.; Lojo, L.; López-Muñiz, B.; Fernández-Melon, J.; Núñez, B.; Silva-Fernández, L.; Veiga Cabello, R.; et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with interstitial lung disease using unstructured healthcare data and machine learning. RMD Open 2024, 10, e003353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rea, G.; Sverzellati, N.; Bocchino, M.; Lieto, R.; Milanese, G.; D’Alto, M.; Bocchini, G.; Maniscalco, M.; Valente, T.; Sica, G. Beyond Visual Interpretation: Quantitative Analysis and Artificial Intelligence in Interstitial Lung Disease Diagnosis “Expanding Horizons in Radiology”. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dianat, B.; La Torraca, P.; Manfredi, A.; Cassone, G.; Vacchi, C.; Sebastiani, M.; Pancaldi, F. Classification of pulmonary sounds through deep learning for the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases secondary to connective tissue diseases. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 160, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.; Happaerts, S.; Gyselinck, I.; Staes, M.; Derom, E.; Brusselle, G.; Burgos, F.; Contoli, M.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Franssen, F.M.E.; et al. Collaboration between explainable artificial intelligence and pulmonologists improves the accuracy of pulmonary function test interpretation. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2201720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan, J.; Hofmanninger, J.; Nenning, K.H.; Prayer, F.; Röhrich, S.; Sverzellati, N.; Poletti, V.; Tomassetti, S.; Weber, M.; Prosch, H.; et al. Unsupervised machine learning identifies predictive progression markers of IPF. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Exarchos, K.P.; Gkrepi, G.; Kostikas, K.; Gogali, A. Recent Advances of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Interstitial Lung Diseases. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, X.; Yin, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Shi, J.; Weng, D.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, W.; et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis mortality risk prediction based on artificial intelligence: The CTPF model. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 878764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pawar, S.P.; Talbar, S.N. Two-stage hybrid approach of deep learning networks for interstitial lung disease classification. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 7340902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hwang, H.J.; Seo, J.B.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, E.Y.; Park, B.; Bae, H.J.; Kim, N. Content-Based Image Retrieval of Chest CT with Convolutional Neural Network for Diffuse Interstitial Lung Disease: Performance Assessment in Three Major Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Korean J. Radiol. 2021, 22, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wong, A.; Lu, J.; Dorfman, A.; McInnis, P.; Famouri, M.; Manary, D.; Lee, J.R.H.; Lynch, M. Fibrosis-Net: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Prediction of Pulmonary Fibrosis Progression From Chest CT Images. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 764047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.S.; Zhou, H.Y.; Dong, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.J.; Wu, Y.F.; Yuan, S.H.; Tang, M.Y.; et al. Real-World Verification of Artificial Intelligence Algorithm-Assisted Auscultation of Breath Sounds in Children. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 627337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Romei, C.; Tavanti, L.M.; Taliani, A.; De Liperi, A.; Karwoski, R.; Celi, A.; Palla, A.; Bartholmai, B.J.; Falaschi, F. Automated Computed Tomography analysis in the assessment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis severity and progression. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 124, 108852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, T.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L. Automatic Lung Segmentation Based on Texture and Deep Features of HRCT Images with Interstitial Lung Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 2045432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacob, J.; Bartholmai, B.J.; Rajagopalan, S.; Kokosi, M.; Nair, A.; Karwoski, R.; Walsh, S.L.; Wells, A.U.; Hansell, D.M. Mortality prediction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Evaluation of computer-based CT analysis with conventional severity measures. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.C.; Roth, H.R.; Gao, M.; Lu, L.; Xu, Z.; Nogues, I.; Yao, J.; Mollura, D.; Summers, R.M. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Computer-Aided Detection: CNN Architectures, Dataset Characteristics and Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2016, 35, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferrara, P.; Battiato, S.; Polosa, R. Progress and prospects for artificial intelligence in clinical practice: Learning from COVID-19. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1855–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, F.; Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, S. Computed tomography–based artificial intelligence in lung disease—Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. MedComm—Future Med. 2024, 3, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Heo, K.; Kang, S.J. Real-Time Sleep Apnea Diagnosis Method Using Wearable Device without External Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops, PerCom Workshops, Austin, TX, USA, 23–27 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.F.; Hung, C.M.; Ko, S.C.; Cheng, K.C.; Chao, C.M.; Sung, M.I.; Hsing, S.C.; Wang, J.J.; Chen, C.J.; Lai, C.C.; et al. An artificial intelligence system to predict the optimal timing for mechanical ventilation weaning for intensive care unit patients: A two-stage prediction approach. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 935366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cosgrove, G.P.; Bianchi, P.; Danese, S.; Lederer, D.J. Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: The INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hofman, D.E.; Magrì, T.; Moor, C.C.; Richeldi, L.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Waseda, Y. Patient-centered care in pulmonary fibrosis: Access, anticipate, and act. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoyer, N.; Prior, T.S.; Bendstrup, E.; Shaker, S.B. Diagnostic delay in IPF impacts progression-free survival, quality of life and hospitalisation rates. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2022, 9, e001276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arts, L.; Lim, E.H.T.; van de Ven, P.M.; Heunks, L.; Tuinman, P.R. The diagnostic accuracy of lung auscultation in adult patients with acute pulmonary pathologies: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lynch, D.A.; Travis, W.D.; Müller, N.L.; Galvin, J.R.; Hansell, D.M.; Grenier, P.A.; King, T.E., Jr. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: CT features. Radiology 2005, 236, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.J.; Flaherty, K. Pulmonary function testing in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006, 3, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moran-Mendoza, O.; Ritchie, T.; Aldhaheri, S. Fine crackles on chest auscultation in the early diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e000815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flietstra, B.; Markuzon, N.; Vyshedskiy, A.; Murphy, R. Automated analysis of crackles in patients with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm. Med. 2011, 2011, 590506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barnes, H.; Humphries, S.M.; George, P.M.; Assayag, D.; Glaspole, I.; Mackintosh, J.A.; Corte, T.J.; Glassberg, M.; Johannson, K.A.; Calandriello, L.; et al. Machine learning in radiology: The new frontier in interstitial lung diseases. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e41–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.B.; Van Moorsel, C.H.M.; Kazemier, K.M.; Marshall, D.J.; van ‘t Hul, A.J. Machine-learning algorithm to improve cohort identification in patients with interstitial lung disease [Letter]. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, U.; Shah, S.Y.; Alotaibi, A.A.; Althobaiti, T.; Ramzan, N.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Shah, S.A. Portable UWB RADAR sensing system for transforming subtle chest movement into actionable micro-doppler signatures to extract respiratory rate exploiting ResNet algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 23518–23526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykanat, M.; Kılıç, Ö.; Kurt, B.; Saryal, S. Classification of lung sounds using convolutional neural networks. J. Image Video Proc. 2017, 2017, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.U.D.; Khan, N.A.; Thakur, G.; Gautam, S.P.; Ali, M.; Alam, P.; Alshehri, S.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Shakeel, F. Utilization of Artificial Intelligence in Disease Prevention: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Implications for the Healthcare Workforce. Healthcare 2022, 10, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferreira-Cardoso, H.; Jácome, C.; Silva, S.; Amorim, A.; Redondo, M.T.; Fontoura-Matias, J.; Vicente-Ferreira, M.; Vieira-Marques, P.; Valente, J.; Almeida, R.; et al. Lung Auscultation Using the Smartphone—Feasibility Study in Real-World Clinical Practice. Sensors 2021, 21, 4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, J.J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Lee, H.P. Review on the Advancements of Stethoscope Types in Chest Auscultation. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kevat, A.; Kalirajah, A.; Roseby, R. Artificial intelligence accuracy in detecting pathological breath sounds in children using digital stethoscopes. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Attia, Z.I.; Harmon, D.M.; Behr, E.R.; Friedman, P.A. Application of artificial intelligence to the electrocardiogram. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4717–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, Y.; Hyon, Y.; Jung, S.S.; Lee, S.; Yoo, G.; Chung, C.; Ha, T. Respiratory sound classification for crackles, wheezes, and rhonchi in the clinical field using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayo Clinic News Network. AI Enables Early Identification, Intervention in Debilitating Lung Disease. Mayo Clinic. 2022. Available online: https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/ai-enables-early-identification-intervention-in-debilitating-lung-disease/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Butterfly Network. Butterfly iQ+ User Guide: AI-Guided Lung Ultrasound and Stethoscope Platform. 2021. Available online: https://www.butterflynetwork.com (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Cottin, V.; Hirani, N.A.; Hotchkin, D.L.; Nambiar, A.M.; Ogura, T.; Otaola, M.; Skowasch, D.; Park, J.S.; Poonyagariyagorn, H.K.; Wuyts, W.; et al. Presentation, diagnosis and clinical course of the spectrum of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, A.; Asan, O. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Patient Safety Outcomes: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e18599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Botha, N.N.; Segbedzi, C.E.; Dumahasi, V.K.; Maneen, S.; Kodom, R.V.; Tsedze, I.S.; Akoto, L.A.; Atsu, F.S.; Lasim, O.U.; Ansah, E.W. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: A scoping review of perceived threats to patient rights and safety. Arch. Public Health 2024, 82, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sgalla, G.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Sverzellati, N.; Fletcher, S.; Cerri, S.; Dimitrov, B.; Nikolic, D.; Barney, A.; Pancaldi, F.; Larcher, L.; et al. “Velcro-type” crackles predict specific radiologic features of fibrotic interstitial lung disease. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manfredi, A.; Cassone, G.; Cerri, S.; Venerito, V.; Fedele, A.L.; Trevisani, M.; Furini, F.; Addimanda, O.; Pancaldi, F.; Della Casa, G.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a velcro sound detector (VECTOR) for interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients: The InSPIRAtE validation study (INterStitial pneumonia in rheumatoid ArThritis with an electronic device). BMC Pulm. Med. 2019, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Champlin, J.; Edwards, R.; Pipavath, S. Imaging of Occupational Lung Disease. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 54, 1077–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeyratne, U.R.; Swarnkar, V.; Setyati, A.; Triasih, R. Cough sound analysis can rapidly diagnose childhood pneumonia. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 41, 2448–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, H.P.; Zhou, Z.J.; Du, N.; Zhong, E.H.; Zhai, K.; Liu, N.; Zhou, L. Artificial intelligence-powered remote monitoring of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 134, 1546–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Topalovic, M.; Das, N.; Burgel, P.R.; Daenen, M.; Derom, E.; Haenebalcke, C.; Janssen, R.; Kerstjens, H.A.M.; Liistro, G.; Louis, R.; et al. Pulmonary Function Study Investigators: Artificial intelligence outperforms pulmonologists in the interpretation of pulmonary function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zech, J.R.; Badgeley, M.A.; Liu, M.; Costa, A.B.; Titano, J.J.; Oermann, E.K. Variable generalization performance of a deep learning model to detect pneumonia in chest radiographs: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sheller, M.J.; Edwards, B.; Reina, G.A.; Martin, J.; Pati, S.; Kotrotsou, A.; Milchenko, M.; Xu, W.; Marcus, D.; Colen, R.R.; et al. Federated learning in medicine: Facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richeldi, L.; Cottin, V.; Würtemberger, G.; Kreuter, M.; Calvello, M.; Sgalla, G. Digital Lung Auscultation: Will Early Diagnosis of Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease Become a Reality? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.; Liu, Z.; Singh, A.; Lange, M.; Boddu, P.; Gong, J.Q.X.; Lee, J.; DeMarco, C.; Cao, C.; Platt, S.; et al. Interstitial lung disease diagnosis and prognosis using an AI system integrating longitudinal data. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ueda, D.; Kakinuma, T.; Fujita, S.; Kamagata, K.; Fushimi, Y.; Ito, R.; Matsui, Y.; Nozaki, T.; Nakaura, T.; Fujima, N.; et al. Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Review and recommendations. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Feng, Q.; Du, M.; Zou, N.; Hu, X. Fair machine learning in healthcare: A review. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. The National Digital Health Mission (NDHM) Roadmap and AI Governance; NHS AI Lab: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbacke, R.; Melhus, Å.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. How Explainable Artificial Intelligence Can Increase or Decrease Clinicians’ Trust in AI Applications in Health Care: Systematic Review. JMIR AI 2024, 3, e53207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Anazi, S.; Al-Omari, A.; Alanazi, S.; Marar, A.; Asad, M.; Alawaji, F.; Alwateid, S. Artificial intelligence in respiratory care: Current scenario and future perspective. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2024, 19, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vega, R.; Dehghan, M.; Nagdev, A.; Buchanan, B.; Kapur, J.; Jaremko, J.L.; Zonoobi, D. Overcoming barriers in the use of artificial intelligence in point of care ultrasound. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| ILD Category | ILD Subtypes | Common Auscultation Findings | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias (IIPs) | Fine velcro-like inspiratory crackles, typically basal | IPF: Poor (3–5 yr survival); Others: Good if treated early | |

| Autoimmune and Connective Tissue Disease-Associated ILDs | Fine bilateral basal crackles; systemic features vary | UIP pattern: Poor; NSIP or antibody-responsive types: Favorable | |

| Exposure-Related ILDs | Fine inspiratory crackles (basal/mid/upper depending on etiology) | Prognosis varies: improves with early withdrawal of exposure; advanced fibrosis worsens outcome | |

| Airspace-Filling ILDs |

| Diffuse wheeze or fine crackles; pneumothorax in LAM/PLCH | LAM/PAP: Good prognosis with therapy; PLCH: Improves with smoking cessation |

| Granulomatous ILDs |

| Fine crackles and wheeze (upper/mid zones); coarse crackles in advanced stages | Variable: Coarse crackles, B-symptoms, and advanced imaging findings indicate worse outcome |

| Other ILDs |

| Fine crackles (diffuse or lobe-specific); wheeze in CEP | AEP: Excellent recovery; CEP: Recurrences common; PLC: Very poor prognosis (~50% 2-month mortality) |

| Model/Technique | Input Features | Feature Extraction | Application | Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN–LSTM | Raw audio + spectrogram | Spatial + temporal modeling | ILD progression monitoring | Not reported | [52] |

| Transformer (emerging) | MFCC/time-series | Self-attention across respiratory cycles | Breath cycle interpretation (experimental) | Not reported | [52] |

| DS-CNN | MFCC + STFT spectrograms | Time–frequency fusion | Velcro crackle detection | 85.74% | [53] |

| Bi-ResNet | MFCC + STFT spectrograms | Bidirectional residual learning | Fine crackle classification | 97.82% | [54] |

| Improved Random Forest | MFCC + db4 Wavelet | CFS + GR + SU + Ensemble decision trees | Multi-class respiratory sound classification | 99.04% | [55] |

| AdaBoost | MFCC + db4 Wavelet | Ensemble boosting | Baseline ensemble for lung sound classification | 96.63% | [55] |

| Gradient Boosting (GB) | MFCC + db4 Wavelet | Boosted decision trees | Alternate ensemble model | 95.11% | [55] |

| Wavelet Transform (db4) | Raw lung sound | Time–frequency decomposition for transient events | Velcro crackle enhancement (preprocessing aid) | – | [52,55] |

| Non AI Traditional Methods: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year and Author | Study | Technique | Results and Limitations |

| 2025, Boros et al. [60] | Value of Spirometry in Detecting Volume Restriction in ILD Patients | Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Analysis → Analyzed pulmonary function data from 1173 ILD patients over 5 years → Spirometry and whole-body plethysmography performed using MasterLab—‘Jaeger’ equipment following ERS standards → Compared TLC (Total Lung Capacity) and VC (Vital Capacity) for detecting volume restriction | Mean TLC was significantly lower than VC (93.7% vs. 98.0%, p < 0.001), with abnormal TLC more frequent (22.8%) than reduced VC (17.8%). VC showed 69.3% sensitivity and 88.5% PPV for restriction, but findings are limited to patients without airway obstruction, reducing applicability to more severe ILD. |

| 2024, Kobayashi et al. [61] | ILD-NSCLC-GAP Scoring and Staging System | Modified ILD-GAP Index → A modified ILD-GAP index scoring system used to predict the incidence of ILD-AE and prognosis in patients with NSCLC and interstitial lung disease (ILD) → ILD subtypes, sex, age, and percent forced vital capacity (%FVC) are considered → The patients are categorized into stages I (0–1), II (2–3), and III (4–5) based on their index score → Data was collected from patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for NSCLC between 2002 and 2014 | The modified ILD-GAP index predicted ILD-AE incidence and prognosis in NSCLC with ILD, showing higher risk and lower one-year survival with increasing scores (70.8% in stage I vs. 10% in stage III). Findings are limited by retrospective, single-center data and exclusion of patients receiving some chemotherapy or radiotherapy regimens. |

| 2024, Hirata et al. [62] | ILD-GAPM Model for Prognosis in ILD | Retrospective, Observational Study → Analyzed 179 ILD patients (including IPF, iNSIP, CVD-IP, CHP, and UC-ILD) → Compared the ILD-GAP scoring system and ILD-GAPM, which combines ILD-GAP with the monocyte ratio → Pulmonary function tests (PFTs), HRCT, and clinical parameters were used to assess disease progression and prognosis | ILD-GAPM outperformed ILD-GAP in predicting 3-year ILD-related events (AUC: 0.747 vs. 0.710). Significant differences were observed in Kaplan–Meier survival curves based on monocyte ratio. ILD-GAPM was especially effective for predicting IPF progression. However, limitations include the single-center design, small sample size, and lack of longitudinal data for monocyte ratio changes. |

| 2024, Thrainsson et al. [63] | VATS for Diagnosing ILD | Surgical Lung Biopsy (SLB) with VATS → Retrospective cohort study involving 68 patients who underwent VATS lung biopsy for suspected ILD → Preoperative tests included CT scans, spirometry, and bronchoscopy | VATS achieved a 92.6% diagnostic yield, most often diagnosing NSIP (29.4%) and UIP (23.5%). Limitations include the retrospective nature, small sample size, and lack of AI integration in the diagnostic process. |

| 2023, Zanatta et al. [64] | CCL18 as a Biomarker for ILD and PF-ILD in Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies | Prospective Cohort Study → Analyzed serum levels of CCL18 and OX40L in 93 IIMs patients → HRCT was used to detect ILD and classify it into patterns (NSIP, UIP, OP) → PFTs were measured to evaluate lung function at baseline and at 24 months | CCL18 serum levels were significantly higher in IIMs-ILD patients (p < 0.0001). High CCL18 levels were independently associated with PF-ILD at the 24-month follow-up. The study found CCL18 to be a reliable predictor for PF-ILD (OR 1.006, p = 0.005). The ROC curve for CCL18 identified an optimal threshold of 303.5 ng/mL, with 82% sensitivity and 83% NPV. Limitations include the small sample size and lack of external validation. |

| 2022, Le Guen et al. [65] | Clinical Impact of Surgical Lung Biopsy for Interstitial Lung Disease in a Reference Center | Patient Selection → Elective surgical lung biopsy for suspected ILD → Preoperative Multidisciplinary Discussion (MDD) (to confirm indication and biopsy sites) → Pre-op evaluation → Surgical Lung Biopsy (VATS or open) → Post-op care & monitoring → MDD1 (without biopsy results) → MDD2 (with biopsy results) → Compare MDD1 vs. MDD2 → Assess diagnostic & treatment changes → Record complications & outcomes (90-day follow-up) → Statistical analysis | In this study of 73 ILD patients, surgical lung biopsy (SLB) was safe, with no deaths and a 17% complication rate. It provided a definitive diagnosis in 95% of cases and led to changes in diagnosis and treatment in 48% and 45% of patients, respectively. SLB remains a valuable tool when noninvasive methods are inconclusive. The study’s main limitations include its retrospective, single-center design, which may affect generalizability. |

| 2022, McDermott G et al. [66] | Associations of the MUC5B promoter variant with timing of interstitial lung disease and rheumatoid arthritis onset | Cohort identification and recruitment → DNA extraction → Genotyping of MUC5B promoter variant (rs35705950) → Collection of clinical data (ILD and RA onset) → Integration of genetic and clinical datasets → Statistical analysis (survival and regression models) → Clinical interpretation of association with disease progression. | The MUC5B promoter variant was associated with earlier onset of ILD in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients but did not influence timing of RA onset. Carriers developed ILD sooner after RA diagnosis, underscoring its role in early lung disease progression and risk prediction in RA. |

| 2022, Gui et al. [67] | Role of Anti-Ro52 Antibodies in IIM-ILD Prognosis | Serological and Clinical Data Analysis → Retrospective cohort study of 267 IIM-ILD patients with various myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs) → Anti-Ro52 antibodies were detected in anti-MDA5 and anti-Jo1 positive patients using immunoblot assays → Clinical, laboratory, and imaging data were analyzed to assess the association between anti-Ro52 positivity and disease progression | Anti-Ro52 antibody positivity was linked to a higher risk of rapidly progressive ILD, worse prognosis, and greater mortality, particularly in patients also carrying anti-MDA5 antibodies, who showed more severe clinical features including Gottron sign. Generalizability is limited by the retrospective design and absence of longitudinal follow-up. |

| 2022, Oishi et al. [68] | 1-Minute Sit-to-Stand Test for Desaturation in ILD | Retrospective Observational Study → Compared 1 min sit-to-stand test (1STST) with the 6 min walk test (6MWT) in 116 ILD patients → Measured pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) nadir during both tests → Analyzed correlation and agreement between 1STST and 6MWT for desaturation detection | Nadir SpO2 during the 1STST strongly correlated with the 6MWT (ρ = 0.82, p < 0.0001) and showed high agreement (κ = 0.82) in detecting desaturation <90%. The 1STST outperformed DLCO for identifying desaturation, though findings are limited by the retrospective design and possible selection bias. |

| 2022, Harari et al. [69] | The 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) as a Primary End-Point in ILD | Literature Review & Methodological Analysis → Reviewed multiple ILD trials and studies using 6MWT as a primary endpoint in clinical trials → Focused on 6MWD (6 min walk distance) and oxygen desaturation | The 6MWD emerged as a reliable endpoint for ILD trials, particularly in advanced ILD and ILD-PH, where it predicted clinical worsening and disease progression. Interpretation is limited by variability in 6MWT methodology, influence of patient factors and environment, and a “floor effect” in advanced disease that reduces sensitivity to change over time. |

| 2021, Yan et al. [70] | Lung Ultrasound (LUS) for ILD Detection | Lung Ultrasound (LUS) → A semi-quantitative approach using B-lines to assess ILD severity → 14 intercostal spaces (ICSs) were assessed using a GE-E9 Doppler ultrasound machine with a line array probe → B-line scores were calculated based on the number of B-lines observed, with scoring for mild (6–15 B-lines), moderate (16–30 B-lines), and severe (>30 B-lines) cases | LUS showed 93% sensitivity and 73% specificity for ILD detection, with 94% PPV and 67% NPV. LUS was found to be an effective, non-invasive, radiation-free screening tool for ILD, though it performed slightly worse than HRCT, with some false negatives in early-stage ILD. The study was limited by its retrospective design and small sample size, as well as challenges in detecting deep lung abnormalities. |

| 2021, Matson et al. [71] | MMP-7 as a Prognostic Biomarker in Scleroderma-Associated ILD | Retrospective Cohort Study → Analyzed serum levels of MMP-7, CXCL13, and CCL18 in 115 SSc-ILD patients → HRCT, PFTs, and lung biopsy were used to assess disease severity and lung function → Immunohistochemistry and qPCR were used to measure MMP-7 expression in lung tissue | Higher MMP-7 levels were significantly associated with lower FVC and DLCO (p < 0.001), indicating worse lung function. Patients with higher MMP-7 had an increased risk of death or lung transplant (HR = 2.05, p = 0.009). MMP-7 levels categorized into low, medium, and high tertiles correlated with disease severity (p < 0.001). Limitations include the lack of a validation cohort and the study being limited to a single-center cohort. |

| 2020, Kim et al. [72] | KL-6 as a Prognostic Biomarker in RA-ILD | KL-6 Assay → Measured KL-6 levels in plasma using the Nanopia KL-6 assay (latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric method) → 84 RA-ILD patients included in the study, with HRCT scans used to identify UIP patterns → Multivariate logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard analyses were used to assess the relationship between KL-6 levels and disease prognosis | High KL-6 levels (>685 U/mL) were found to be independently associated with increased mortality risk (HR = 2.984, p = 0.016) and UIP patterns (OR = 5.173, p = 0.005). The study found that KL-6 could serve as a reliable prognostic biomarker for RA-ILD, especially in those with a UIP pattern, suggesting its potential role in early disease assessment. However, limitations included the small sample size and lack of longitudinal data to further confirm findings. |

| 2020, Pugashetti et al. [73] | ILD-Screen: A Diagnostic Prediction Tool for ILD | Prospective Cohort Study → Developed ILD-Screen, a diagnostic tool derived from PFT variables like TLC, FEV1, DLCO, and clinical factors → Logistic regression models identified predictive factors for ILD → Validated in independent cohorts and applied prospectively over a 1-year period | ILD-Screen showed 79% sensitivity and 83% specificity in identifying ILD cases. It improved diagnostic workflow by increasing the rate of chest CT imaging and reducing time to diagnosis. Prospective validation showed that ILD-Screen significantly outperformed clinical features like dyspnea and cough. However, limitations include selection bias and the need for further validation in broader patient populations. |

| 2019, Newton et al. [74] | Telomere length and genetic variant associations with interstitial lung disease progression and survival | Patient Enrollment & Sample Collection → Clinical Data Collection (Demographics, ILD subtype, progression, survival) → DNA Extraction from Blood Samples → Measurement of Telomere Length (qPCR or Southern blot assay) → Genotyping of Genetic Variants (SNP arrays or sequencing) → Statistical Analysis (Associations of telomere length & genetic variants with ILD progression and survival) → Interpretation of Results & Correlation with Clinical Outcomes | Shorter telomere length in ILD was linked to faster disease progression and reduced survival, with genetic variants in telomere maintenance also influencing outcomes. These findings support telomere biology as a prognostic marker and potential therapeutic target. Interpretation is limited by the observational design, small sample size for rare variants, use of a specialized cohort, and reliance on blood-cell telomere length, which may not reflect lung tissue status. |

| 2017, Yamakawa et al. [75] | KL-6 and SP-D as Predictive Biomarkers for ILD in SSc/MCTD | Retrospective Cohort Study → Analyzed serum KL-6 and SP-D levels in 40 patients (29 with SSc and 11 with MCTD) → Pulmonary function tests (FVC, DLCO) and HRCT were used to evaluate ILD severity and progression | KL-6 levels correlated with DLCO and HRCT disease extent, while changes in KL-6 were associated with FVC decline. SP-D was identified as a significant predictor of FVC decline. The study suggested KL-6 for monitoring and SP-D for predicting FVC decline. Limitations include the small sample size and the retrospective nature of the study. |

| 2017, Kropski et al. [76] | Genetic Testing in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) | Literature Review & Cohort Study → This study reviewed genetic contributions to familial interstitial pneumonia (FIP) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), focusing on genetic variants like those related to telomerase and surfactant proteins → The study also examined the role of genetic testing for families at high risk of IPF, providing insights into screening and counseling protocols | Mutations in TERT, SFTPC, and SFTPA2 were found to significantly contribute to familial IPF cases. The study suggests genetic testing for at-risk families to detect telomere dysfunction. However, the study acknowledged limitations such as limited data on disease penetrance and the lack of standardized clinical guidelines for genetic screening in routine practice. |

| 2015, Bauer et al. [77] | Influence of Autoimmune Biomarkers on ILD Prognosis | Case-Control Study → Retrospective study on 3573 ILD patients at Mayo Clinic, Rochester → Assessed autoimmune biomarkers like ANA, RF, and aldolase through serological tests → Analyzed associations with ILD, adjusting for age, gender, race, smoking history, and CTD | Positive ANA and RF were significantly associated with increased odds of ILD. ANA remained an independent risk factor for ILD after adjustments (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.33–2.17). Patients with ILD alone had poorer survival than those with CTD-ILD (p = 0.001), and positive biomarkers did not improve prognosis. The study’s retrospective design and biases in biomarker testing due to the varied application of tests across the patient population were key limitations. |

| AI-Based Methods: | |||

| Year and Author | Study | Technique | Results and Limitations |

| 2025, Guo et al. [78] | AI and Machine Learning for IPF Diagnostics | Neural Network Model → Utilized gene expression datasets from the GEO database to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in IPF vs. healthy controls → Employed Lasso regression and Random Forest algorithms to screen for potential biomarkers → Artificial Neural Network (ANN) built for IPF classification, with ROC curve and AUC metrics for diagnostic performance → Immune infiltration analysis conducted with the CIBERSORT tool to explore immune cell interactions | The neural network model showed excellent diagnostic performance, with AUC values for biomarkers ASPN, COMP, and GPX8 being 0.94, 0.99, and 0.94, respectively. The immune analysis revealed significant changes in immune cell populations in IPF, highlighting their role in pathogenesis. Limitations include small sample sizes and the inherent “black-box” nature of the ANN model, which may affect interpretability. |

| 2025, Gompelmann et al. [79] | AI-powered evaluation of lung function for diagnosis of interstitial lung disease. | Data Collection → Data Preprocessing → Feature Extraction → AI Model Training → AI Evaluation → Model Validation → Result Interpretation → Diagnosis of ILD. | AI support improved pulmonologists’ interpretation of pulmonary function tests, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and enabling earlier ILD detection. Findings are limited by the small, retrospective dataset, short AI exposure (4–6 months), and lack of evaluation of long-term outcomes or comparisons across different AI models. |

| 2025, Guiot et al. [80] | Automated AI-based image analysis for quantification and prediction of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis patients | Patient selection & CT acquisition → Image preprocessing (normalization, noise reduction) → AI model training on annotated CT scans (ML/DL algorithms) → Automated lung region segmentation → Quantification of ILD features (fibrosis, ground-glass opacity) → Extraction of imaging biomarkers → Statistical analysis & validation against clinical/functional data → Prediction of ILD progression and outcomes. | AI-based image analysis accurately quantified ILD in systemic sclerosis, correlating well with clinical tests and predicting progression more effectively than traditional methods, offering faster and more consistent assessment. Its broader use is limited by the single-disease focus, retrospective design, and absence of long-term prospective validation. |

| 2024, Teramachi et al. [57] | Deep Learning for Predicting Acute Exacerbation and Mortality in ILD | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network → Applied to longitudinal ILD patient data for predicting acute exacerbations (AE-ILD) and mortality → Managed temporal gaps through data imputation → Incorporated key features such as neutrophil counts, CRP, ILD-GAP score, and environmental exposures (e.g., particulate matter). | The LSTM model demonstrated higher prediction accuracy than Cox Proportional Hazards models, with C-index values of 0.78–0.85 in internal and external validation cohorts. Its use is limited by retrospective data, missing external predictors such as viral infections, and challenges in incorporating environmental variables effectively. |

| 2024, Huang et al. [81] | Proteomics-Based Classifier for ILD Diagnosis | Machine learning on plasma proteomics → High-throughput assays used to analyze plasma from 1247 IPF and 352 CTD-ILD patients → Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for feature selection → Four models (Support Vector Machine, LASSO regression, Random Forest, Imbalanced Random Forest) trained on selected features for diagnosis. | The proteomic classifier (PC37) achieved strong diagnostic performance with AUCs of 0.85–0.90 in test cohorts and 0.94–0.96 in external datasets, with sensitivity of 78.6–80.4% and specificity of 76–84.4%. The composite diagnosis score model reached 82.9% accuracy for single-sample classification. Generalizability is limited by reliance on blood-based biomarkers and the relatively small training and testing datasets. |

| 2024, Felder et al. [82] | Computer-Based Imaging in ILD: QCT and AI | Quantitative Computed Tomography (QCT) and AI-based image analysis → Utilized deep learning algorithms (e.g., SOFIA, DTA) for pattern identification and progression prediction on HRCT images → Textural analysis and data-driven techniques were applied to quantify fibrosis, honeycombing, and ground-glass opacities (GGO) | QCT with AI provided more reliable and precise measurements than traditional semiquantitative methods, improving disease progression predictions and facilitating early detection of fibrotic changes. However, challenges include data privacy concerns, integration with clinical practice, and the need for explainable AI models to increase clinician trust. |

| 2024, Guerra et al. [83] | U-Net CNN for CT Scan Analysis in Progressive Fibrotic ILD | U-Net Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) → Developed U-Net CNN for quantification of ILD progression in CT scans → 32 patients with fibrotic ILD (IPF, i-NSIP, u-IIP) were included → CT scans were processed to identify fibrotic changes and correlate these changes with FVC (Forced Vital Capacity) | The U-Net CNN showed a significant correlation between ILD% and FVC decline (r = –0.30, p = 0.004). An ILD progression rate ≥4%/year was linked to poor prognosis (p = 0.001), with ROC analysis yielding an AUC of 0.83, indicating good predictive accuracy. Limitations include the small sample size and the need for external validation. |

| 2024, Xu et al. [84] | Classification and Recognition of Lung Sounds Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: A Literature Review. | Record lung sounds → Remove noise from the recordings → Extract patterns or frequency → Enhance the Data → Choose and Train a machine leaning Model → Classify the Sounds → Evaluate Performance. | AI and machine learning methods can accurately classify lung sounds, with deep learning models outperforming traditional approaches. Model performance improves with careful feature selection and incorporation of additional datasets, supporting faster and more accurate respiratory diagnoses. Broader clinical use requires further validation to ensure reliability and ease of application in real-world settings. |

| 2024, Román Ivorra JA et al. [85] | Prevalence and clinical characteristics of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with interstitial lung disease using unstructured healthcare data and machine learning | Identification of Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort → Extraction of Unstructured Clinical Notes → Natural Language Processing (NLP) Preprocessing → Creation of ILD-related indicators (fibrosis, honeycombing, ground glass) → Machine Learning Model Development (e.g., random forest) → Assess performance (AUC, sensitivity, specificity) → ILD Prevalence Estimation & Clinical Correlation | A machine-learning model detected ILD in 6.9% of more than 22,000 RA patients—higher than rates identified with structured data alone. Using NLP with machine learning on free-text notes revealed clinically relevant patterns and improved early ILD detection in RA. Findings are limited by the retrospective design, dependence on unstructured notes with variable quality, and uncertain generalizability across healthcare systems without external validation. |

| 2023, Rea et al. [86] | AI and Quantitative Imaging in ILD Diagnosis | AI-based image analysis → Integration with HRCT to detect ILD patterns → Quantitative software tools provide accurate, repeatable, and objective lung assessments → AI supports recognition and classification of features such as ground-glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrosis → Models also incorporate clinical, genomic, and proteomic metadata to enhance diagnostic accuracy. | AI-enhanced HRCT analysis improved diagnostic precision compared with visual interpretation, providing quantitative, reproducible assessments and reducing observer bias. Its broader use is limited by variable performance across populations, the need for large training datasets, and incomplete integration of clinical variables such as biomarkers. |

| 2023, Dianat et al. [87] | Classification of Pulmonary Sounds for ILD Diagnosis | Deep Learning-based Classification → Used Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for classifying pulmonary sounds recorded with a digital stethoscope → Pre-processing pipeline involved Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) for noise reduction and data augmentation using techniques like SpecAugment → Focused on identifying velcro crackles associated with ILD, particularly in patients with connective tissue diseases (CTD) | The model achieved 91–93% diagnostic accuracy in classifying lung sounds, showing strong potential for use in large-scale screening programs. The pre-processing with VMD and SpecAugment significantly improved model performance. However, limitations include potential sensitivity to background noise in real-world applications and the need for high-quality auscultation data. The model’s ability to generalize to other forms of ILD requires further validation across diverse clinical settings. |

| 2023, Das et al. [88] | Collaboration between Pulmonologists and explainable AI (XAI) | Multicenter, Intervention Study → Pulmonologists interpreted 24 PFT reports in two steps: control (without XAI suggestions) and intervention (with XAI suggestions) → The study involved two phases: monocentric (P1) with 16 pulmonologists and multicentric (P2) with 62 pulmonologists → XAI suggestions were generated using a machine learning model predicting diseases like COPD, ILD, and asthma with Shapley values (SVs) providing transparency into AI decisions | With XAI support, diagnostic accuracy improved significantly—preferential by 10.4% and differential by 9.4% in Phase 1, and by 5.4% and 8.7% in Phase 2 (all p < 0.001). Pulmonologists still outperformed the model, but results highlight XAI as a useful adjunct in diagnostic decision-making. The effect may have been reduced by deliberately including incorrect AI suggestions, while limitations include small sample size and possible learning effects from repeated testing. |

| 2023, Beverin et al. [58] | Predicting TLC from Spirometry Data Using Machine Learning | Machine Learning Model Development → Three tree-based models (CatBoost, XGBoost, and Random Forest) were trained on 51,761 spirometry data points to predict total lung capacity (TLC) → The models used patient characteristics (age, height, gender, weight) and spirometry metrics (FVC, FEV1, etc.) → The best model (CatBoost) was validated on an independent test set of 1402 patients | The CatBoost model predicted TLC with a mean squared error (MSE) of 560.1 mL. It showed high sensitivity (83%) and specificity (92%) in identifying restrictive ventilatory impairment. Limitations include the study’s reliance on Caucasian patient data, the potential overestimation of TLC in obstructive diseases, and the absence of validation in non-Caucasian populations. |

| 2023, Wu et al. [56] | Identifying potential biomarkers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through machine learning analysis | Gene expression data collection (IPF and controls) → Preprocessing (quality control, normalization, filtering) → Identification of differentially expressed genes → Feature selection with machine learning (Random Forest, SVM, LASSO) → Model training and validation for IPF classification → Biomarker selection based on feature importance → Functional enrichment and pathway analysis → Verification through literature and experimental evidence. | Machine learning on gene expression data identified key biomarkers for IPF through differential gene analysis and feature selection, with further biological analysis linking them to fibrosis and immune pathways. These biomarkers show potential for early diagnosis and treatment guidance. Generalizability is limited by the small, non-diverse public datasets, reliance on retrospective validation, and lack of functional or multi-omics integration such as proteomics. |

| 2023, Pan et al. [89] | Unsupervised machine learning identifies predictive progression markers of IPF | Data collection (HRCT scans of IPF patients) → Preprocessing (normalization, segmentation) → Feature extraction (radiomic/imaging features) → Dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) → Unsupervised clustering (k-means, hierarchical) → Identification of patient subgroups → Analysis of progression markers by comparing clinical outcomes and imaging features across clusters → Validation of predictive markers. | Unsupervised machine learning on CT scans identified distinct IPF patient subgroups with different progression patterns, with specific imaging features predicting faster worsening and aiding risk stratification. Generalizability is limited by the small, retrospective, single-center datasets and the exclusion of clinical or molecular variables, highlighting the need for larger prospective studies. |

| 2023, Exarchos KP et al. [90] | Recent Advances of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Interstitial Lung Diseases | Data collection → Preprocessing of medical data (CT scans, clinical parameters, lung function tests) → Feature extraction (radiomic features, biomarkers, PFT indices) → AI model development (ML/DL methods: CNN, SVM, etc.) → Model training and validation with annotated datasets → Evaluation (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, ROC) → Clinical application for diagnosis, prognosis, and disease monitoring → Integration into workflow as decision-support and radiology assistance tools. | AI, particularly CNN-based deep learning on HRCT, achieved performance comparable to expert radiologists in classifying ILD subtypes, assessing severity, and predicting progression. Incorporating clinical and functional data further improved diagnostic accuracy and patient stratification, supporting AI-driven decision tools. Limitations include reliance on small, heterogeneous datasets, lack of standardized imaging and annotation, limited interpretability of “black-box” models, and scarce prospective validation or clinical integration. |

| 2022, Wu X et al. [91] | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Mortality Risk Prediction Based on Artificial Intelligence: The CTPF Model | Gather clinical data and HRCT images of IPF patients → Extract quantitative CT features and clinical parameters → Data Preprocessing → Apply techniques like LASSO to identify key predictors → Train machine learning models → Assess model performance using AUC, sensitivity, and specificity → Select the best model and integrate into the CTPF system → Predict individual patient mortality risk | The CTPF model, combining clinical and CT imaging features, predicted mortality risk in IPF patients, with logistic regression achieving the best performance (AUC 0.85) for stratifying patients into high- and low-risk groups. Limitations include the retrospective, single-center design, small sample size, reliance on specific CT software, and lack of external validation, reducing generalizability until confirmed in broader cohorts. |

| 2022, Pawar et al. [92] | Two-Stage Hybrid Approach of Deep Learning Networks for Interstitial Lung Disease Classification | Data Acquisition → Preprocessing (e.g., resizing, normalization, augmentation) → Stage 1—Feature Extraction using CNN Model 1 → Stage 2—Feature Extraction using CNN Model 2 → Feature Fusion (combining features from both CNNs) → Classification Layer (fully connected layers + softmax) → Output: ILD Class Prediction | Pawar and Talbar’s two-stage hybrid deep learning method, combining features from two CNN models, improved ILD image classification accuracy compared with single models and traditional approaches, offering a promising tool to support radiologists. Its broader application is limited by the small dataset, high computational demands, lack of clinical data integration, and absence of extensive independent validation. |

| 2021, Hwang et al. [93] | CBIR System for DILD Diagnosis Using CT | Content-Based Image Retrieval (CBIR) → Lung segmentation using deep CNNs → Classification of six DILD patterns (honeycombing, reticular opacity, emphysema, ground-glass opacity, consolidation, normal lung) → Quantification of these patterns across HRCT slices → Feature extraction and similarity assessment using Euclidean distance to match query CTs with database images. | The CBIR system achieved 61.7% top-1 retrieval accuracy and 81.7% within the top-5, performing best for UIP, where 96.7% of retrieved CTs matched the query class. It showed promise in supporting radiologists, but performance varied across ILD patterns (notably lower in COP) and requires validation on larger, more diverse datasets. |

| 2021, Wong et al. [94] | Fibrosis-Net: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Prediction of Pulmonary Fibrosis Progression From Chest CT Images | Preprocessing of Images by CT → CT scans divided into 2D axial image patches → Each patch labeled based on fibrosis progression (stable vs. progressive) → Custom Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture → Training the CNN → Model performance evaluated on validation/test sets → Use of Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) for visualizing regions contributing to prediction → Prediction of Pulmonary Fibrosis Progression. | The study demonstrated that Fibrosis-Net, a customized deep learning model, can be used as a non-invasive, image-based tool to predict pulmonary fibrosis progression, potentially aiding clinicians in early risk stratification and treatment decisions. The study used a small, single-center dataset and only CT images, limiting generalizability. It offered binary predictions without clinical data and had limited interpretability despite Grad-CAM. Being retrospective, it may also include bias. |

| 2021, Zhang et al. [95] | Real-World Verification of Artificial Intelligence Algorithm-Assisted Auscultation of Breath Sounds in Children. | Collect breath sounds from pediatric patients → Preprocess and clean audio recordings → Input processed audio into the AI algorithm → Extract relevant acoustic features from breath sounds → Classify breath sounds into categories (e.g., normal, wheeze, crackle) → Generate AI-assisted diagnostic results → Compare AI outputs with clinical evaluation for validation. | An AI-assisted auscultation system accurately detected abnormal breath sounds such as wheezes and crackles in children, demonstrating reliability in real-world clinical settings and supporting more consistent diagnoses where expert auscultation is limited. Its generalizability is restricted by the small, single-center cohort, potential susceptibility to background noise and recording variability, reliance on subjective clinician comparisons, and the absence of multicenter validation. |

| 2020, Romei et al. [96] | Automated CT Analysis for IPF Severity and Progression | CALIPER software → Automated lung parenchyma segmentation → Classification into CT patterns (reticular, honeycombing, ground-glass, normal) → Quantification of fibrosis and PVRS as % lung volume → Provides reproducible HRCT assessment of disease progression without manual input. | The study demonstrated that CALIPER-derived parameters, specifically ILD% and PVRS%, were strongly correlated with Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) measurements, offering a reliable tool for tracking disease progression. However, the study had limitations due to its retrospective nature and sample size, requiring further validation with larger, prospective studies. |

| 2019, Pang et al. [97] | Automatic Lung Segmentation for ILD Diagnosis | Hybrid Segmentation Model → Combines texture features and deep features for lung segmentation → Texture features are extracted using Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) to analyze lung patterns → Deep features are obtained using U-Net, a convolutional neural network (CNN), to refine segmentation → Images are pre-processed using Wiener filtering to remove noise from HRCT images | The segmentation model achieved high accuracy with a Dice Similarity Coefficient of 89.4%, comparable to state-of-the-art methods. By combining texture and deep learning features, segmentation performance was enhanced. Limitations include reliance on well-annotated datasets and sensitivity to noise or image quality, which may hinder real-world application |

| 2017, Jacob et al. [98] | Using Computer-Based CT Analysis for Mortality Prediction in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis | CALIPER tool → Lung tissue segmentation using density-based morphology → Airway segmentation via 3D region-growing algorithm → Pulmonary vessel detection with multi-scale tubular enhancement filters → Vessel volume quantification by size thresholds (PVV < 5 mm2, PVV < 10 mm2, PVV > 5 mm2) → Extraction of ILD features (ground-glass opacities, honeycombing, reticular patterns) using texture analysis and image processing. | CALIPER-derived measurements, particularly pulmonary vessel volume (PVV), were stronger predictors of mortality than visual CT scores. PVV, honeycombing, and CPI combined with CALIPER data emerged as key mortality indicators. Limitations include the lack of external validation and the need for further refinement of segmentation algorithms to improve predictive accuracy. |