Italian Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients: Overview of Their Quality of Life and Unmet Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

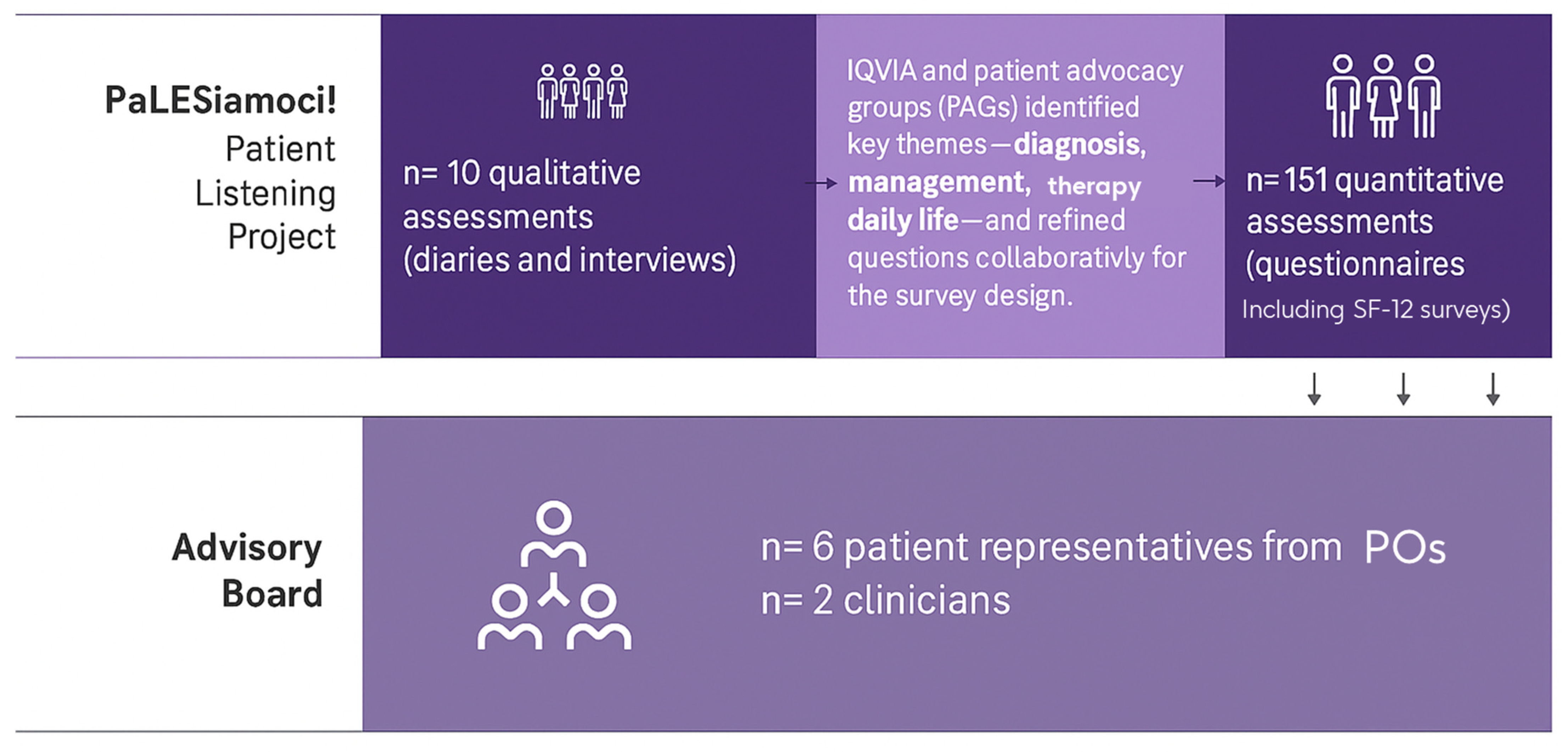

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Analysis

2.2. Quantitative Analysis

2.3. Advisory Board Meeting

- The six patient representatives discussed the topics independently.

- Separately, the two rheumatologists discussed the same topics.

- Afterwards, a joint session allowed patients and clinicians to exchange views, resolve discrepancies, and build consensus.

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement Statement (PPI)

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

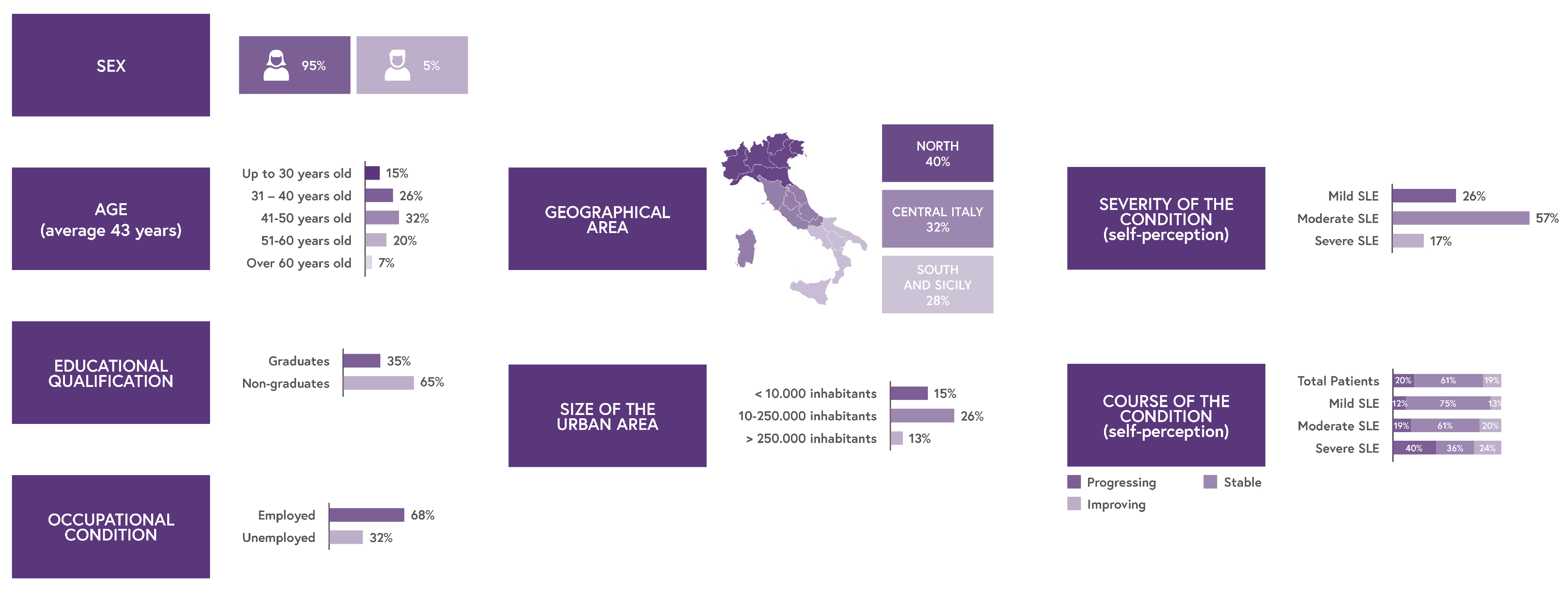

3.2.1. Demographics

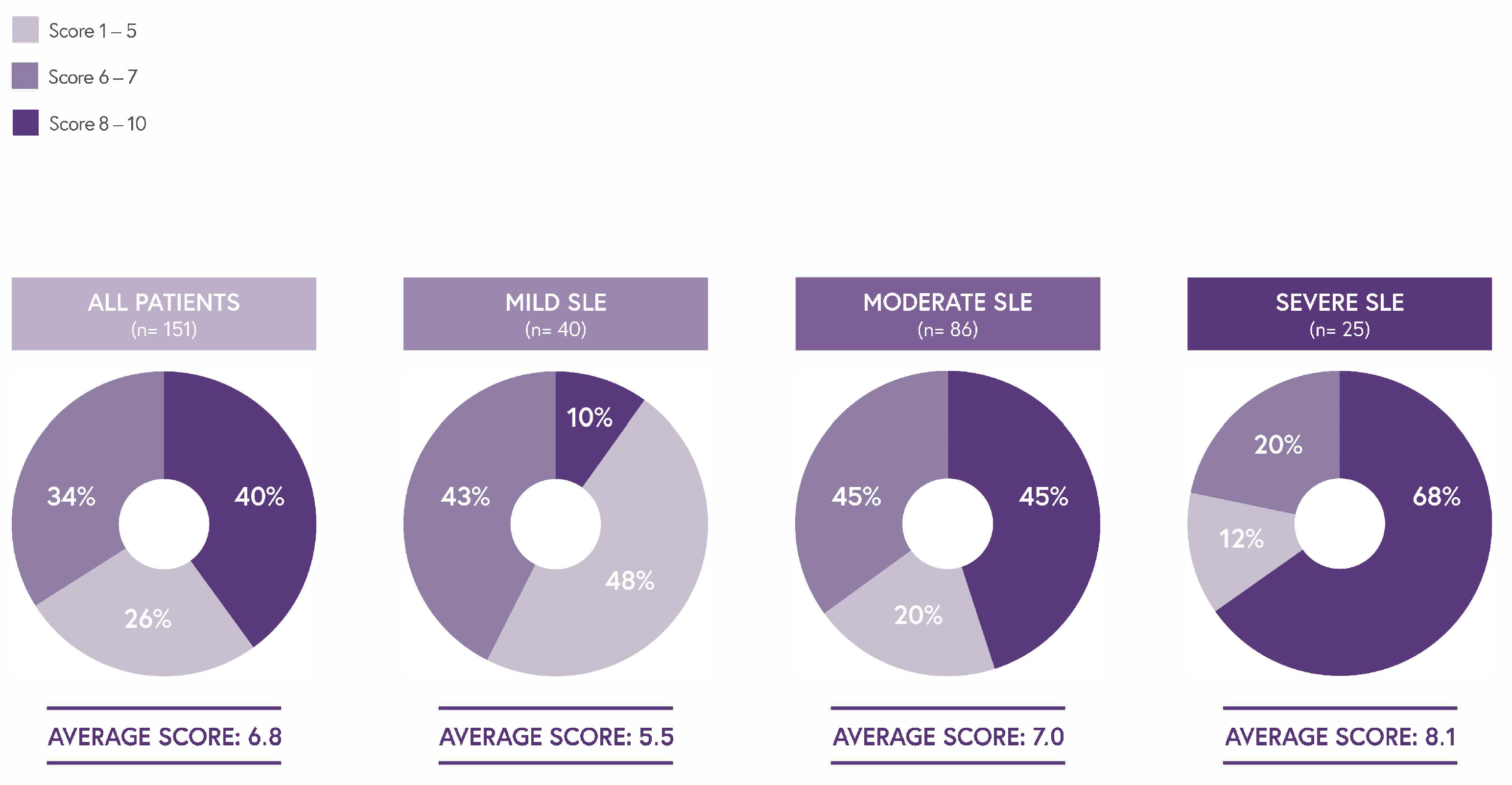

3.2.2. 12-Item Medical Outcome Short Form (SF-12)

3.2.3. Descriptive Questions

- Symptom Prevalence and Perceptions

- Impact of SLE on Daily Life, Employment, and Leisure Activities

- Patient Journey Steps

- ○

- The Diagnosis

- ○

- Follow-Up

- ○

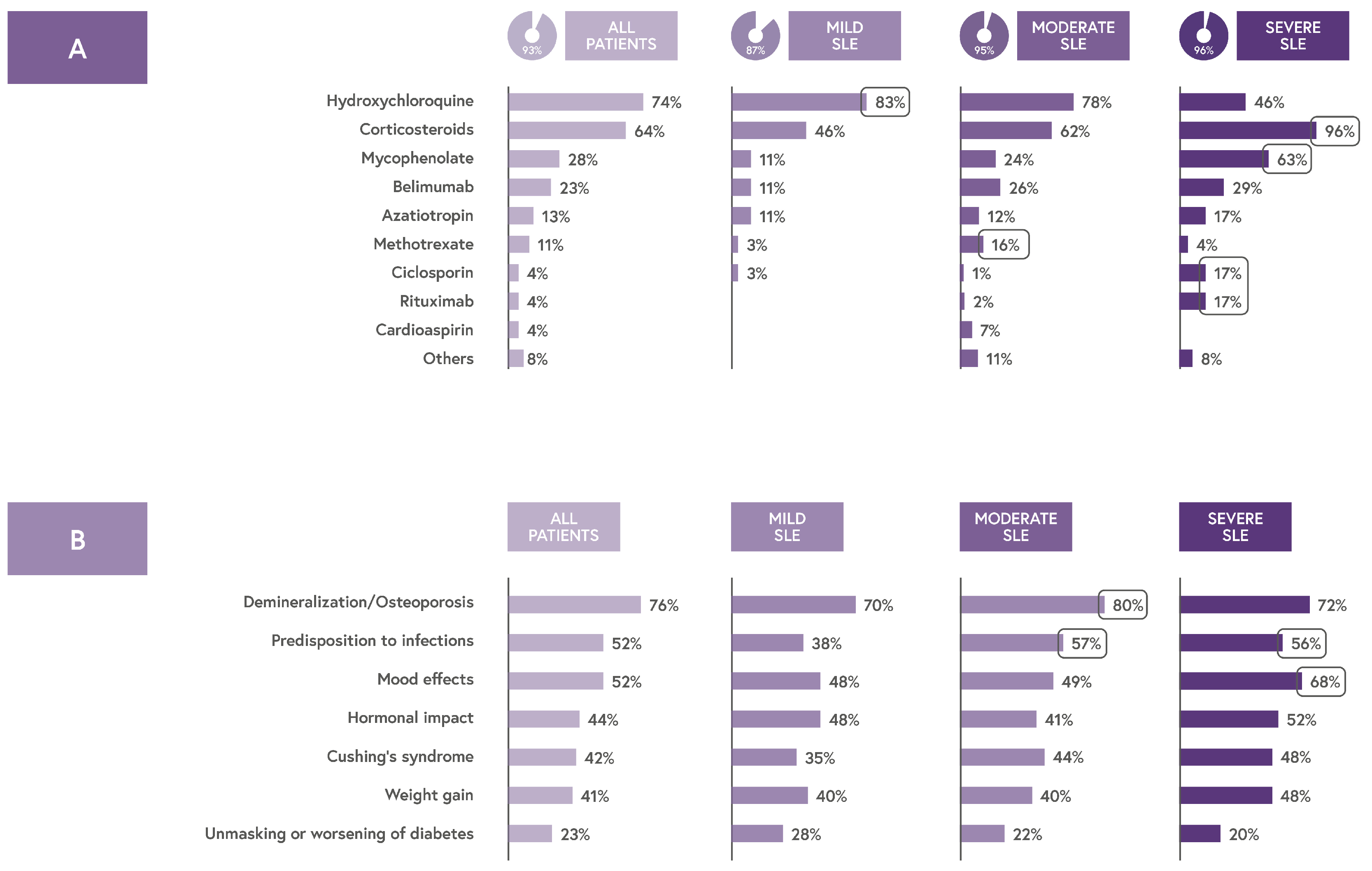

- Therapeutic Regimen

- ○

- Critical Issues and Unmet Needs

- Increased financial support to cover therapy-related expenses (61%);

- A more multidisciplinary approach to treatment, particularly to manage therapy-related adverse events (59%);

- Establishment of more specialized SLE centers across Italy to improve access to care (56%) (Figure S7).

- Greater economic assistance for purchasing health-related consumer goods (29%);

- Stronger interdisciplinary coordination among healthcare providers (31%);

- Easier access to benefits under Law 104 to facilitate medical visits and examinations (29%).

3.3. The Advisory Board Phase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| AB | Advisory Board |

| AE | Adverse Event |

| APMARR | Associazione Nazionale Persone con Malattie Reumatologiche e Rare |

| CAWI | Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing |

| EULAR | European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology |

| GSK | GlaxoSmithKline |

| IQVIA | Name of the contracted survey service provider |

| Istat | Istituto Nazionale di Statistica |

| MCS | Mental Component Summary |

| PCS | Physical Component Summary |

| PO | Patient Organization |

| PPI | Patient and Public Involvement |

| PROM | Patient-Reported Outcome Measure |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SF-12 | 12-item Medical Outcome Short Form |

| SLE | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| SSN | Servizio Sanitario Nazionale (Italian National Health Service) |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.1.1. Patient Diary: “Diario Pazienti LES”

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| H1 | Personal background (age, education, lifestyle, personality, etc.) | Open-ended (written text) |

| H2 | Description of how diagnosis was communicated | Open-ended (written text, optional image) |

| H3 | First thoughts and emotional reaction to diagnosis | Open-ended (written text, optional image) |

| H4 | Perception of SLE (metaphors, symbolic description) | Open-ended (written text) |

| H5 | Imagined dialogue with SLE | Open-ended (dialogue bubbles) |

| H6 | Experience and emotions related to therapy | Open-ended (written text, optional image) |

| H7 | Relationship with the physician(s) | Open-ended (written text, analogies/examples) |

| H8 | Challenges in everyday life and moments of greater difficulty | Open-ended (written text, optional image) |

| H9 | Emotional and relational impact (identity, body image, relationships) | Open-ended (written text) |

| H10 | Unmet needs, suggestions for services, and what would help the most today | Open-ended (written text) |

Appendix A.1.2. Interview Discussion Guide: “Questionario PALESIAMOCI”

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| I1 | Patient’s illness journey: symptoms, diagnosis, emotional reaction | Semi-structured interview |

| I2 | Communication of diagnosis and understanding of disease | Semi-structured interview |

| I3 | Pathway to and experience with treatment center | Semi-structured interview |

| I4 | Relationship with medical specialist(s) and experience during visits | Semi-structured interview |

| I5 | Current and past therapies, treatment satisfaction | Semi-structured interview |

| I6 | Emotional relationship with therapy (ally, burden, etc.) | Semi-structured interview |

| I7 | Difficulties in managing SLE in daily life | Semi-structured interview |

| I8 | Emotional impact, identity changes, self-perception | Semi-structured interview |

| I9 | Effect on work, relationships, and support from caregivers | Semi-structured interview |

| I10 | Experience with follow-up and multidisciplinary care | Semi-structured interview |

| I11 | Use of informational sources and channels | Semi-structured interview |

| I12 | Role and experience with patient associations | Semi-structured interview |

| I13 | Suggestions for improving the patient’s care journey and support system | Semi-structured interview |

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.2.1. English Translation of the SLE Patient Questionnaire

Section A—Demographics & Clinical Information

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| A1 | What is your gender? | Male/Female |

| A2 | What is your age? | Numeric input |

| A3a | Which region do you live in? | Single choice |

| A3b | Which province do you live in? | Single choice |

| A3c | Approximate number of inhabitants in your city? | Numeric input |

| A4 | What is your highest level of education? | None/Primary/Middle/High school/University/Postgraduate |

| A5 | Age at which you were diagnosed with SLE? | Numeric input |

| A6 | Time between first symptoms and diagnosis? | Weeks/Months/Years + Numeric input/I don’t remember |

| A7 | Which doctors did you consult before diagnosis? | Multiple choice |

| A8 | Number of doctors seen before SLE diagnosis? | Numeric input |

| A9 | Which doctor diagnosed your SLE? | Multiple choice |

| A10 | Symptoms that led you to seek medical help? | Multiple choice |

| A11 | Current symptoms? | Multiple choice |

| A12 | Symptoms that most affect your daily life? | Multiple choice |

| A13 | Symptoms that worry you the most? | Multiple choice |

| A14 | How would you describe your disease? | Mild/Moderate/Severe |

| A15 | How is your disease currently evolving? | Stable/Improving/Progressing |

| A16 | Was the diagnosis clearly explained by your doctor? | Very/Quite/A little/Not at all |

| A17 | Did you receive advice from healthcare professionals? | Yes, very/Yes, somewhat/Yes, but not much/No advice received |

| A18 | Did you receive support (psychologist, nurse, etc.)? | Yes, very useful/Yes, somewhat/Yes, not useful/No support |

Section B—Follow-Up & Healthcare Use

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| B1 | Are you followed by a multidisciplinary SLE center? | Yes/No |

| B2 | Which specialists are part of the team? | Multiple choice |

| B3 | Which specialists have you seen in the past year? | Multiple choice |

| B4 | Number of visits per specialist in the past year? | Numeric input |

| B5 | Public vs. private visits? | Numeric input |

| B6 | Who is your primary specialist? | Single choice |

| B7a | Are all specialists in the same structure? | Yes/No |

| B7b | Is the center in your city/region? | Same city/Same region/Different region |

| B8 | Why did you go private for some visits? | Multiple choice |

| B9 | Annual cost of private visits? | Numeric input (Euro) |

| B10 | Why did you choose your treatment center? | Multiple choice |

| B11 | Satisfaction with center (various aspects)? | Scale 1–10 |

| B12 | Overall satisfaction with center? | Scale 1–10 |

| B13 | How many centers have you changed? | Numeric input |

| B14 | Can you complete all prescribed exams/visits? | Always/Sometimes/Often not/Other |

| B15 | Is your center a recognized reference for SLE? | Absolutely/Quite/Not really/No |

Section C—Treatments & Adherence

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| C1 | Is your SLE in remission or active phase? | Remission/Active |

| C2 | Are you currently on medication for SLE? | Yes/No |

| C3a–d | What drugs do you take, and how? | Name, route, dosage, place |

| C4a | Satisfaction with administration mode? | Very/Somewhat/Not much/Not at all |

| C4b | Preferred administration mode? | Open-ended |

| C4c | Preference: home vs. hospital? | Visual analog scale |

| C5 | Can you follow your daily therapy? | Multiple choice |

| C6 | Did you purchase non-reimbursed products? | Yes/No by item |

| C7 | Annual cost of non-reimbursed products? | Numeric input (Euro) |

| C8 | What corticosteroid effects worry you most? | Multiple choice |

Section D—Daily Life Impact

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| D1 | How would you rate your general health? | Excellent to Poor scale |

| D2 | Limitations in moderate physical activities? | Yes, a lot/A little/No |

| D3 | Limitations climbing stairs? | Yes, a lot/A little/No |

| D4 | Physical health affected work/daily activities? | Yes/No—Reduced output/Limited tasks |

| D5 | Emotional state affected work/daily activities? | Yes/No—Reduced output/Lost focus |

| D6 | Pain interference with usual work? | Scale 1–5 |

| D7 | How often felt calm/energetic/sad? | Scale: Always to Never |

| D8 | Interference with social/family/friend life? | Scale: Always to Never |

| D9 | Overall interference with daily life? | Scale 1 (Very little) to 10 (Very much) |

| D10 | Agreement with SLE impact statements? | Scale 1 (Not at all) to 10 (Completely agree) |

Section E—Work & Insurance

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| E1 | What is your current work status? | Employed/Unemployed/Retired/Student/Other |

| E2 | How many work days lost per year? | Numeric input |

| E3 | Did you change job due to SLE? | Yes/No |

| E4 | Are you hired as a protected category? | Yes/No |

| E5 | Do you use Law 104 benefits? | Yes/No |

| E6 | Do you take time off for SLE visits? | Yes/No |

| E7–E10 | Job/study changes due to SLE? | Yes/No + Reasoning |

| E11 | Job reduction due to SLE? | Yes/No + How |

| E12–E13 | Student-specific questions? | Days missed/Course choice influence |

| E14 | Do you receive disability or care benefits? | Multiple choice |

| E15 | Do you have private/enterprise insurance? | Yes/No |

| E16 | Was insurance denied due to SLE? | Yes/No |

Section F—Critical Issues & Patient Needs

| Question ID | Question | Response Type/Options |

| F1 | Most critical issues managing SLE? | Multiple choice |

| F2 | Top 3 critical issues? | Ranking |

| F3 | Helpful interventions for SLE patients? | Multiple choice |

| F4 | Top 3 helpful supports? | Ranking |

| F5 | Other information sources used? | Multiple choice |

Appendix A.3

- Adherence: In your opinion, are patients aware of the importance of continuous therapeutic adherence in SLE, including in remission or relapse moments?

- Awareness: What are the drugs that patients perceive as essential to stop the progression of the disease? Does this information derive from clinicians or other sources?

- Awareness: Are patients aware of non-pharmacological strategies to reduce the progression of the disease?

- Awareness: Considering SLE-related organ damage progression, is there awareness among patients on how irreversible this could be?Are they aware that organ damage could be correlated either to disease progression or to therapy?How do patients inform (through the clinician, PAG, autonomously)?What can be done to improve awareness?

- Patients’ journey: How is patients’ journey? Do they have discontinuity periods, considering cure reference points? Does this impact adherence?

- Implementation: Which activities could the industry implement to understand and meet SLE patients’ need for the best?

References

- Barber, M.R.W.; Falasinnu, T.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Clarke, A.E. The global epidemiology of SLE: Narrowing the knowledge gaps. Rheumatology 2023, 62 (Suppl. S1), i4–i9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.; Antonazzo, I.C.; Zamparini, M.; Fornari, C.; Borrelli, C.; Boarino, S.; Bettiol, A.; Mattioli, I.; Palladino, P.; Ferrari, E.Z.; et al. Epidemiology of SLE in Italy: An observational study using a primary care database. Lupus Sci. Med. 2024, 11, e001162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, D.; Yao, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, Q. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: A comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsias, G.K.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Boletis, J.; Bombardieri, S.; Cervera, R.; Dostal, C.; Font, J.; Gilboe, I.M.; Houssiau, F.; Huizinga, T.; et al. EULAR points to consider for conducting clinical trials in systemic lupus erythematosus: Literature based evidence for the selection of endpoints. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, Y.; Iwasaki, T.; Doi, H.; Tsuji, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Ueno, K.; Inaba, R.; Kozuki, T.; Taniguchi, M.; Tabuchi, Y.; et al. Correlation between irreversible organ damage and the quality of life of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: The Kyoto Lupus Cohort survey. Lupus 2021, 30, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, H.M.; Abdel-Nasser, A.M.; Kasem, A.H.; Elameen, N.F.; Omar, G.M. Pulmonary involvement: A potential independent factor for quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2023, 32, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Huang, F.F.; O’Neill, S.G. Patient-Reported Outcomes for Quality of Life in SLE: Essential in Clinical Trials and Ready for Routine Care. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touma, Z.; Gladman, D.D.; Ibañez, D.; Urowitz, M.B. Is There an Advantage Over SF-36 with a Quality of Life Measure That Is Specific to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus? J. Rheumatol. 2011, 38, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primavera, D.; Carta, M.G.; Romano, F.; Sancassiani, F.; Chessa, E.; Floris, A.; Cossu, G.; Nardi, A.E.; Piga, M.; Cauli, A. Quality of Life in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Other Chronic Diseases: Highlighting the Amplified Impact of Depressive Episodes. Healthcare 2024, 12, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaigne, B.; Finckh, A.; Alpizar-Rodriguez, D.; Courvoisier, D.; Ribi, C.; Chizzolini, C.; for the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Program for Rheumatoid Arthritis & the Swiss Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort Study Group. Differential impact of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis on health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istat—Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Bes 2014—Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia; Istat: Rome, Italy, 2014; ISBN 88-458-1796-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fanouriakis, A.; Kostopoulou, M.; Andersen, J.; Aringer, M.; Arnaud, L.; Bae, S.C.; Boumpas, D.T. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus: 2023 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrocchi, V.; Visintini, E.; De Marchi, G.; Quartuccio, L.; Palese, A. Patient Experiences of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Findings from a Systematic Review, Meta-Summary, and Meta-Synthesis. Arthritis Care Res. 2022, 74, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.M.; Egede, L.; Faith, T.; Oates, J. Effective Self-Management Interventions for Patients with Lupus: Potential Impact of Peer Mentoring. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 353, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, C.; Bermas, B.; Zibit, M.; Fraser, P.; Todd, D.; Fortin, P.; Massarotti, E.; Costenbader, K. Designing an intervention for women with systemic lupus erythematosus from medically underserved areas to improve care: A qualitative study. Lupus 2013, 22, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovde, A.M.; McFarland, C.A.; Garcia, G.M.; Gallagher, F.; Gewanter, H.; Klein-Gitelman, M.; Moorthy, L.N. Multi-pronged approach to enhance education of children and adolescents with lupus, caregivers, and healthcare providers in New Jersey: Needs assessment, evaluation, and development of educational materials. Lupus 2021, 30, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, V.; Abdou, N.I.; Kimler, B.F.; Lu, N.; Brown, S.; Fridley, B.L. Gender Bias in Human Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Problem of Steroid Receptor Action? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Perricone, C.; Reboldi, G.; Gawlicki, M.; Bartosiewicz, I.; Pacucci, V.; Massaro, L.; Miranda, F.; Truglia, S.; Alessandri, C.; et al. Validation of a disease-specific health-related quality of life measure in adult Italian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: LupusQoL-IT. Lupus 2014, 23, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PCS-12 Score | Δ(PCS-PCSr) | MCS-12 Scores | Δ(MCS-MCSr) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian reference * | 51.2 | 0 | 49.0 | 0 |

| Mild SLE (n = 40) | 43.3 | −7.9 | 38.4 | −10.6 |

| Moderate SLE (n = 86) | 36.9 | −14.3 | 34.7 | 14.3 |

| Severe SLE (n = 25) | 32.0 | −19.2 | 30.3 | −18.7 |

| Average SLE (n = 151) | 37.8 | −13.4 | 35.0 | −14.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moroni, L.; De Marchi, G.; Pelissero, R.; Callori, M.; Agresta, I.; Celano, A.; Cosentino, E.; Tamanini, S.; Delli Carri, A.; Ramirez, G.A.; et al. Italian Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients: Overview of Their Quality of Life and Unmet Needs. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8498. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238498

Moroni L, De Marchi G, Pelissero R, Callori M, Agresta I, Celano A, Cosentino E, Tamanini S, Delli Carri A, Ramirez GA, et al. Italian Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients: Overview of Their Quality of Life and Unmet Needs. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8498. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238498

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoroni, Luca, Ginevra De Marchi, Rosa Pelissero, Mercedes Callori, Italia Agresta, Antonella Celano, Elisa Cosentino, Silvia Tamanini, Alessia Delli Carri, Giuseppe Alvise Ramirez, and et al. 2025. "Italian Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients: Overview of Their Quality of Life and Unmet Needs" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8498. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238498

APA StyleMoroni, L., De Marchi, G., Pelissero, R., Callori, M., Agresta, I., Celano, A., Cosentino, E., Tamanini, S., Delli Carri, A., Ramirez, G. A., Nano, A., Quartuccio, L., & Dagna, L. (2025). Italian Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients: Overview of Their Quality of Life and Unmet Needs. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8498. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238498