Automatic Segmentation of Intraluminal Thrombus in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Based on CT Images: A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

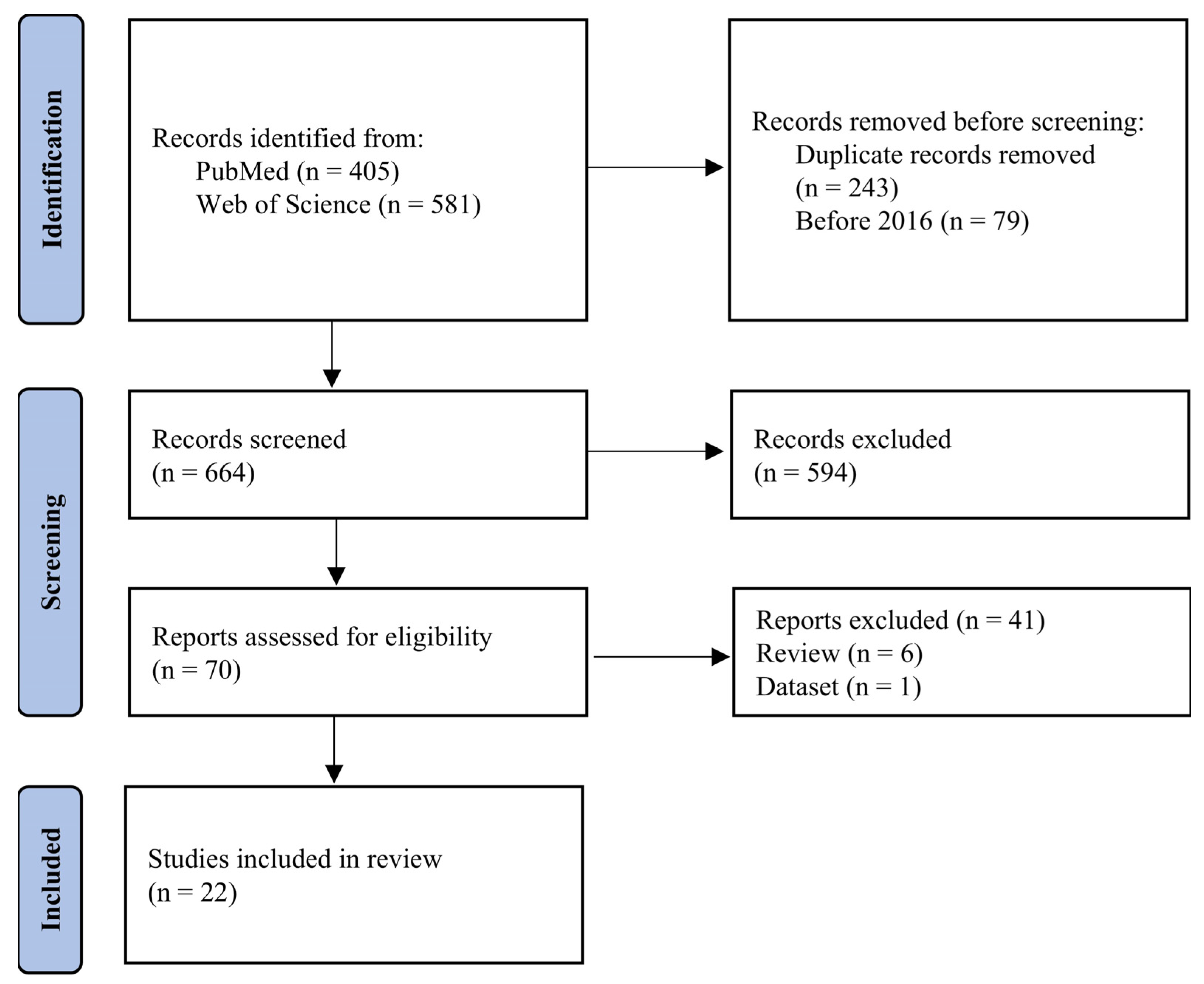

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Process

2.4. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. 2D Deep Learning Network

3.2. 3D Deep Learning Network

3.3. Preoperative and Postoperative Image

3.4. Data Lack in ILT Segmentation

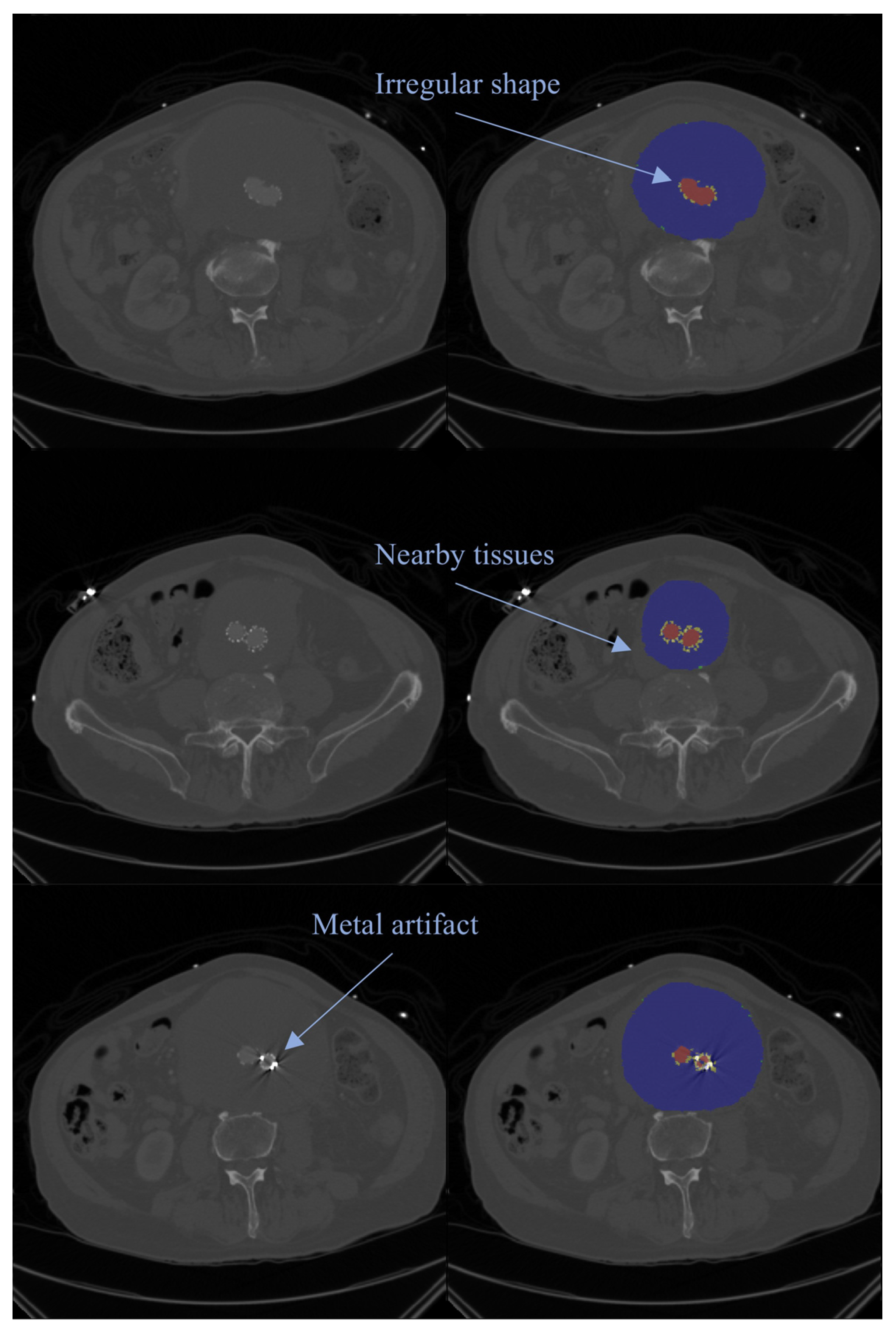

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAA | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AL | Active learning |

| Bi-CLSTM | Bi-directional convolutional long short-term memory |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CTA | Computed tomography angiography |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| DL | Deep learning |

| DSC | Dice similarity coefficient |

| DUS | Duplex ultrasound |

| EVAR | Endovascular aneurysm repair |

| FCN | Fully convolutional network |

| HD95 | Hausdorff distance 95% |

| ILT | Intraluminal thrombus |

| IOU | Intersection over union |

| NCCT | Non-contrast computed tomography |

| OAR | Open aneurysm repair |

| SDLU | Similarity-based dynamic linking |

| WSS | Wall shear stress |

References

- Kent, K.C. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, M.A.; Ruhlman, M.K.; Baxter, B.T. Inflammatory Cell Phenotypes in AAAs. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 1746–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakalihasan, N.; Michel, J.-B.; Katsargyris, A.; Kuivaniemi, H.; Defraigne, J.-O.; Nchimi, A.; Powell, J.T.; Yoshimura, K.; Hultgren, R. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostakos, J.; Lal, B.K. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 65, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhee, J.T.; Hill, J.S.; Eslami, M.H. The Impact of Gender on Presentation, Therapy, and Mortality of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in the United States, 2001–2004. J Vasc Surg 2007, 45, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikesalingam, A.; Holt, P.J.; Vidal-Diez, A.; Ozdemir, B.A.; Poloniecki, J.D.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Thompson, M.M. Mortality from Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Clinical Lessons from a Comparison of Outcomes in England and the USA. Lancet 2014, 383, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.G.; Brown, L.C.; Sweeting, M.J.; Bown, M.J.; Kim, L.G.; Glover, M.J.; Buxton, M.J.; Powell, J.T. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Growth and Rupture Rates of Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Implications for Surveillance Intervals and Their Cost-Effectiveness. Health Technol. Assess. 2013, 17, 1–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, J.C.; Palmaz, J.C.; Barone, H.D. Transfemoral Intraluminal Graft Implantation for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 5, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D’Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karkos, C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolai, L.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Lanzi, S.; Boc, V.; Bossone, E.; Brodmann, M.; Bura-Rivière, A.; De Backer, J.; Deglise, S.; Della Corte, A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Peripheral Arterial and Aortic Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.V.; O’Donnell, S.D.; Chang, A.S.; Johnson, C.A.; Gillespie, D.L.; Goff, J.M.; Rasmussen, T.E.; Rich, N.M. What Imaging Studies Are Necessary for Abdominal Aortic Endograft Sizing? A Prospective Blinded Study Using Conventional Computed Tomography, Aortography, and Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography. J. Vasc. Surg. 2005, 41, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saida, T.; Mori, K.; Sato, F.; Shindo, M.; Takahashi, H.; Takahashi, N.; Sakakibara, Y.; Minami, M. Prospective Intraindividual Comparison of Unenhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging vs Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography for the Planning of Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 55, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lareyre, F.; Chaudhuri, A.; Flory, V.; Augène, E.; Adam, C.; Carrier, M.; Amrani, S.; Chikande, J.; Lê, C.D.; Raffort, J. Automatic Measurement of Maximal Diameter of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm on Computed Tomography Angiography Using Artificial Intelligence. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 83, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furie, B.; Furie, B.C. In Vivo Thrombus Formation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5 (Suppl. 1), 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr-Rasmussen, C.; Grøndal, N.; Bramsen, M.B.; Thomsen, M.D.; Lindholt, J.S. Mural Thrombus and the Progression of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: A Large Population-Based Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014, 48, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedenborg, J.; Eriksson, P. The Intraluminal Thrombus as a Source of Proteolytic Activity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1085, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos Gonçalves, F.; Baderkhan, H.; Verhagen, H.J.M.; Wanhainen, A.; Björck, M.; Stolker, R.J.; Hoeks, S.E.; Mani, K. Early Sac Shrinkage Predicts a Low Risk of Late Complications after Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Br. J. Surg. 2014, 101, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troutman, D.A.; Chaudry, M.; Dougherty, M.J.; Calligaro, K.D. Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair Surveillance May Not Be Necessary for the First 3 Years after an Initially Normal Duplex Postoperative Study. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikof, E.L.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; Harris, P.L.; White, G.H.; Zarins, C.K.; Bernhard, V.M.; Matsumura, J.S.; May, J.; Veith, F.J.; Fillinger, M.F.; et al. Reporting Standards for Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002, 35, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yushkevich, P.A.; Piven, J.; Hazlett, H.C.; Smith, R.G.; Ho, S.; Gee, J.C.; Gerig, G. User-Guided 3D Active Contour Segmentation of Anatomical Structures: Significantly Improved Efficiency and Reliability. Neuroimage 2006, 31, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffort, J.; Adam, C.; Carrier, M.; Ballaith, A.; Coscas, R.; Jean-Baptiste, E.; Hassen-Khodja, R.; Chakfé, N.; Lareyre, F. Artificial Intelligence in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 72, 321–333.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olabarriaga, S.D.; Rouet, J.-M.; Fradkin, M.; Breeuwer, M.; Niessen, W.J. Segmentation of Thrombus in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms from CTA with Nonparametric Statistical Grey Level Appearance Modeling. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2005, 24, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shum, J.; DiMartino, E.S.; Goldhamme, A.; Goldman, D.H.; Acker, L.C.; Patel, G.; Ng, J.H.; Martufi, G.; Finol, E.A. Semiautomatic Vessel Wall Detection and Quantification of Wall Thickness in Computed Tomography Images of Human Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Med. Phys. 2010, 37, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panayides, A.S.; Amini, A.; Filipovic, N.D.; Sharma, A.; Tsaftaris, S.A.; Young, A.; Foran, D.; Do, N.; Golemati, S.; Kurc, T.; et al. AI in Medical Imaging Informatics: Current Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 2020, 24, 1837–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, A.P.; Li, A.; Lee, M.H.; Forbes, T.L.; Naji, F. A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Vascular Surgery. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 85, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F.; Lê, C.D.; Adam, C.; Carrier, M.; Raffort, J. Bibliometric Analysis on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Vascular Surgery. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 86, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What Kind of Systematic Review Should I Conduct? A Proposed Typology and Guidance for Systematic Reviewers in the Medical and Health Sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Linares, K.; Aranjuelo, N.; Kabongo, L.; Maclair, G.; Lete, N.; Ceresa, M.; García-Familiar, A.; Macía, I.; González Ballester, M.A. Fully Automatic Detection and Segmentation of Abdominal Aortic Thrombus in Post-Operative CTA Images Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Med. Image Anal. 2018, 46, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, J.; Teng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Spiga, F.; Du, M.H.-F.; Gillard, J.H.; Lu, Q.; Liò, P. Neural Network Fusion: A Novel CT-MR Aortic Aneurysm Image Segmentation Method. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2018: Image Processing, SPIE, Houston, TX, USA, 2 March 2018; Volume 10574, pp. 542–549. [Google Scholar]

- López-Linares, K.; Kabongo, L.; Lete, N.; Maclair, G.; Ceresa, M.; García-Familiar, A.; Macía, I.; González Ballester, M.Á. DCNN-Based Automatic Segmentation and Quantification of Aortic Thrombus Volume: Influence of the Training Approach. In Proceedings of the Intravascular Imaging and Computer Assisted Stenting, and Large-Scale Annotation of Biomedical Data and Expert Label Synthesis; Cardoso, M.J., Arbel, T., Lee, S.-L., Cheplygina, V., Balocco, S., Mateus, D., Zahnd, G., Maier-Hein, L., Demirci, S., Granger, E., et al., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- López-Linares, K.; Stephens, M.; García, I.; Macía, I.; Ballester, M.Á.G.; Estepar, R.S.J. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Segmentation Using Convolutional Neural Networks Trained with Images Generated with a Synthetic Shape Model. In Mach Learn Med Eng Cardiovasc Health Intravasc Imaging Comput Assist Stenting (2019); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11794, pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradu, C.; Spampinato, B.; Vrancianu, A.M.; Bérard, X.; Ducasse, E. Fully Automatic Volume Segmentation of Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Computed Tomography Images with Deep Learning Approaches versus Physician Controlled Manual Segmentation. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 246–256.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F.; Adam, C.; Carrier, M.; Raffort, J. Automated Segmentation of the Human Abdominal Vascular System Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Expert System and Supervised Deep Learning. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutti, F.; Fantazzini, A.; Finotello, A.; Müller, L.O.; Auricchio, F.; Pane, B.; Spinella, G.; Conti, M. Deep Learning to Automatically Segment and Analyze Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm from Computed Tomography Angiography. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2022, 13, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Hwang, B.; Lee, S.; Kim, E.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, H. Abdominal Aortic Thrombus Segmentation in Postoperative Computed Tomography Angiography Images Using Bi-Directional Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Architecture. Sensors 2022, 23, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolmanafi, A.; Forneris, A.; Moore, R.D.; Di Martino, E.S. Deep-Learning Method for Fully Automatic Segmentation of the Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm from Computed Tomography Imaging. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1040053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, E.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y.; Hwang, H. Automatic Detection and Segmentation of Thrombi in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Using a Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network with Optimized Loss Functions. Sensors 2022, 22, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradu, C.; Pouncey, A.-L.; Lakhlifi, E.; Brunet, C.; Bérard, X.; Ducasse, E. Fully Automatic Volume Segmentation Using Deep Learning Approaches to Assess Aneurysmal Sac Evolution after Infrarenal Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 76, 620–630.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, T.; Shi, Z.; Fu, W. Fully Automatic Segmentation of Abdominal Aortic Thrombus in Pre-Operative CTA Images Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Technol. Health Care 2022, 30, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, Z.; Fu, W. Development and Comparison of Multimodal Models for Preoperative Prediction of Outcomes After Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 870132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongrat, S.; Pintavirooj, C.; Tungjitkusolmun, S. Reconstruction of 3D Abdominal Aorta Aneurysm from Computed Tomographic Angiography Using 3D U-Net Deep Learning Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th Biomedical Engineering International Conference (BMEiCON), Songkhla, Thailand, 10–13 November 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar, A.; Handa, A.; Shivakumar, N.; Lapolla, P.; Uberoi, R.; Grau, V.; Lee, R. A Deep Learning Pipeline to Automate High-Resolution Arterial Segmentation With or Without Intravenous Contrast. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, e1017-lpagee1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, A.; Handa, A.; Lapolla, P.; Shivakumar, N.; Uberoi, R.; Grau, V.; Lee, R. A Deep Learning Approach to Visualize Aortic Aneurysm Morphology Without the Use of Intravenous Contrast Agents. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, e449–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, N.; Lyu, Z.; Rezaeitaleshmahalleh, M.; Zhang, X.; Rasmussen, T.; McBane, R.; Jiang, J. Automatic Segmentation of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms from CT Angiography Using a Context-Aware Cascaded U-Net. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 158, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, G.; Fantazzini, A.; Finotello, A.; Vincenzi, E.; Boschetti, G.A.; Brutti, F.; Magliocco, M.; Pane, B.; Basso, C.; Conti, M. Artificial Intelligence Application to Screen Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Using Computed Tomography Angiography. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 2125–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; On, S.; Gwon, J.G.; Kim, N. Computed Tomography-Based Automated Measurement of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Using Semantic Segmentation with Active Learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Z.; Mu, N.; Rezaeitaleshmahalleh, M.; Zhang, X.; McBane, R.; Jiang, J. Automatic Segmentation of Intraluminal Thrombosis of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms from CT Angiography Using a Mixed-Scale-Driven Multiview Perception Network (M2Net) Model. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 179, 108838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbi, E.; Ravanelli, D.; Allievi, S.; Raunig, I.; Bonvini, S.; Passerini, A.; Trianni, A. Automatic CTA Analysis for Blood Vessels and Aneurysm Features Extraction in EVAR Planning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserthal, J. Dataset with Segmentations of 117 Important Anatomical Structures in 1228 CT Images 2023. Zenodo 2023, 6802613. [Google Scholar]

- Siriapisith, T.; Kusakunniran, W.; Haddawy, P. A 3D Deep Learning Approach Incorporating Coordinate Information to Improve the Segmentation of Pre- and Post-Operative Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.M.; Ortiz, A.K.; Johnson, A.B. The Vascular Model Repository: A Public Resource of Medical Imaging Data and Blood Flow Simulation Results. J. Med. Devices 2013, 7, 040923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radl, L.; Jin, Y.; Pepe, A.; Li, J.; Gsaxner, C.; Zhao, F.-H.; Egger, J. AVT: Multicenter Aortic Vessel Tree CTA Dataset Collection with Ground Truth Segmentation Masks. Data Brief 2022, 40, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.; Vendt, B.; Smith, K.; Freymann, J.; Kirby, J.; Koppel, P.; Moore, S.; Phillips, S.; Maffitt, D.; Pringle, M.; et al. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): Maintaining and Operating a Public Information Repository. J. Digit. Imaging 2013, 26, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lai, Z.; Liu, S.; Xie, X.; Zhou, X.; Hou, Z.; Ma, X.; Liu, B.; Li, K.; Song, M. SDLU-Net: A Similarity-Based Dynamic Linking Network for the Automated Segmentation of Abdominal Aorta Aneurysms and Branching Vessels. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 100, 106991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F.; Adam, C.; Carrier, M.; Dommerc, C.; Mialhe, C.; Raffort, J. A Fully Automated Pipeline for Mining Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Using Image Segmentation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantazzini, A.; Esposito, M.; Finotello, A.; Auricchio, F.; Pane, B.; Basso, C.; Spinella, G.; Conti, M. 3D Automatic Segmentation of Aortic Computed Tomography Angiography Combining Multi-View 2D Convolutional Neural Networks. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2016; Ourselin, S., Joskowicz, L., Sabuncu, M.R., Unal, G., Wells, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 424–432. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Z.; King, K.; Rezaeitaleshmahalleh, M.; Pienta, D.; Mu, N.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, J. Deep-Learning-Based Image Segmentation for Image-Based Computational Hemodynamic Analysis of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: A Comparison Study. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2023, 9, 067001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, J.F.; Keat, N. Artifacts in CT: Recognition and Avoidance. Radiographics 2004, 24, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, F.E.; Fleischmann, D. CT Artifacts: Causes and Reduction Techniques. Imaging Med. 2012, 4, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tongeren, O.L.R.M.; Vanmaele, A.; Rastogi, V.; Hoeks, S.E.; Verhagen, H.J.M.; de Bruin, J.L. Volume Measurements for Surveillance after Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Using Artificial Intelligence. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 69, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatsaliou, Q.; Lareyre, F.; Raffort, J.; Webster, C.; Bicknell, C.; Pouncey, A.; Ducasse, E.; Caradu, C. Use of Artificial Intelligence With Deep Learning Approaches for the Follow-up of Infrarenal Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2024, 15266028241252097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzl, J.; Uhl, C.; Barb, A.; Henning, D.; Fiering, J.; El-Sanosy, E.; Cuypers, P.W.M.; Böckler, D. Zephyr Study Group Collaborators External Validation of Fully-Automated Infrarenal Maximum Aortic Aneurysm Diameter Measurements in Computed Tomography Angiography Scans Using Artificial Intelligence (PRAEVAorta 2). J. Endovasc. Ther. 2024, 15266028241295563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatinot, A.; Caradu, C.; Stephan, L.; Foret, T.; Rinckenbach, S. Validation Study Comparing Artificial Intelligence for Fully Automatic Aortic Aneurysms Segmentation and Diameter Measurements on Contrast and Noncontrast Enhanced Computed Tomography: A La Mémoire de Lucie Salomon Du Mont (In Memory of Lucie Salomon Du Mont). Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 122, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Krebs, J.R.; Sivaraman, V.B.; Zhang, T.; Kumar, A.; Ueland, W.R.; Fassler, M.J.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Multi-Class Segmentation of Aortic Branches and Zones in Computed Tomography Angiography: The AortaSeg24 Challenge. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.05330. [Google Scholar]

- López-Linares, K.; García, I.; García-Familiar, A.; Macía, I.; Ballester, M.A.G. 3D Convolutional Neural Network for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Segmentation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.00879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, C.M.; Shkolnik, A.D.; Muluk, S.C.; Finol, E.A. Fluid-Structure Interaction in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Effects of Asymmetry and Wall Thickness. Biomed. Eng. Online 2005, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.K.; Liang, N.L.; Vorp, D.A. Artificial Intelligence Framework to Predict Wall Stress in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2022, 10, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siennicka, A.; Adamowicz, M.; Grzesch, N.; Kłysz, M.; Woźniak, J.; Cnotliwy, M.; Galant, K.; Jastrzębska, M. Association of Aneurysm Tissue Neutrophil Mediator Levels with Intraluminal Thrombus Thickness in Patients with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducas, A.A.; Kuhn, D.C.S.; Bath, L.C.; Lozowy, R.J.; Boyd, A.J. Increased Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Activity Correlates with Flow-Mediated Intraluminal Thrombus Deposition and Wall Degeneration in Human Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. JVS Vasc. Sci. 2020, 1, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, A.; McCann, M.; Bradshaw, B.; Shahzad, A.; Buttner, P.; Golledge, J. Thrombus Volume Is Associated with Cardiovascular Events and Aneurysm Growth in Patients Who Have Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 53, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.; Kirkham, E.N.; Haslam, L.; Paravastu, S.C.V.; Kulkarni, S.R. Significance of Preoperative Thrombus Burden in the Prediction of a Persistent Type II and Reintervention after Infrarenal Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 75, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembrechts, M.; Desauw, L.; Coudyzer, W.; Laenen, A.; Fourneau, I.; Maleux, G. Abdominal Aneurysm Sac Thrombus CT Density and Volume after EVAR: Which Association with Underlying Endoleak? Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2024, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F.; Maresch, M.; Chaudhuri, A.; Raffort, J. Ethics and Legal Framework for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence in Vascular Surgery. EJVES Vasc. Forum 2023, 60, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F.; Raffort, J. Artificial Intelligence in Vascular Diseases: From Clinical Practice to Medical Research and Education. Angiology 2025, 33197251324630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F.; Trenner, M. European Research Hub Working Group Collaborative Vascular Research in Europe to Improve Care for Patients With Vascular Diseases: What Is Out There, and How to Participate? EJVES Vasc. Forum 2024, 62, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijken, L.; Zwetsloot, S.; Smorenburg, S.; Wolterink, J.; Išgum, I.; Marquering, H.; van Duivenvoorde, J.; Ploem, C.; Jessen, R.; Catarinella, F.; et al. Developing Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence Models to Predict Vascular Disease Progression: The VASCUL-AID-RETRO Study Protocol. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2025, 15266028251313963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Dataset and Sample Size | Segmentation Target | Model/Method | Performance Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| López-Linares et al., 2017 [28] | 13 postoperative contrast-enhanced CTAs | ILT | Fully Convolutional Networks and a Holistically Nested Edge Detection Network 2D | ILT DSC = 0.89 |

| Wang et al., 2018 [29] | 22 contrast-enhanced CTAs and 22 MRIs of the same patients with AAA | For CT, aorta wall, lumen, ILT, and calcium deposits; for MRI, aorta wall, lumen, and ILT | Fusion-based Deep Convolutional Neural Network 2D | Mean ACC = 0.988 |

| López-Linares et al., 2017 [30] | 20 postoperative and 18 preoperative contrast-enhanced CTAs | ILT only | Fully Convolutional Networks and a Holistically Nested Edge Detection Network 2D | Postoperative ILT DSC = 0.855 ± 0.065; Preoperative ILT DSC = 0.697 ± 0.132 |

| López-Linares et al., 2019 [31] | 28 postoperative CTAs of patients with an infrarenal AAA and who have been treated with EVAR | ILT only | Synthetic Shape Model + 2D DCNN 2D | ILT DSC = 0.84 ± 0.01 |

| Caradu et al., 2021 [32] | 100 contrast-enhanced CTA scans of patients with infrarenal AAA treated by EVAR, including both pre- and post-EVAR multidetector follow-up scans | Lumen and ILT | PRAEVAorta for segmentation: image preprocessing and segmentation of the aortic lumen and thrombus 2D | ILT DSC = 0.81 ± 0.10 |

| Lareyre et al., 2021 [33] | 40 contrast-enhanced and 53 lower-contrast CTAs of infrarenal AAA patients undergoing elective surgery from multi data centers | Lumen, spine, and ILT | Fully CNN with a U-Net architecture 2D | ILT DSC = 0.89 |

| Brutti et al., 2022 [34] | 85 contrast-enhanced CTAs from multi-data centers | ILT and lumen | Multi-view integration approach, 3D + 2D × 3 views 2D + 3D | DSC = 0.89 ± 0.04 |

| Jung et al., 2022 [35] | 60 postoperative CTAs of patients with AAA | ILT only | 2D Bi-CLSTM-based thrombus ROI segmentation method combined with Mask R-CNN 2D | ILT DSC = 0.89 |

| Abdolmanafi et al., 2022 [36] | 6030 CT slices from abdominal CT of 56 patients | Lumen, thrombus, and calcification | 2D multi-stage DL pipeline employing a 2D Residual U-Net with dilated convolutions 2D | Calcified ILT ACC = 0.91 Non-calcified ILT ACC = 0.85 |

| Hwang et al., 2022 [37] | Thrombus CTA scan images from 60 unique patients | ILT only | ResNet50 as backbone combined with a feature pyramid network 2D | ILT F1 = 0.9197 |

| Caradu et al., 2022 [38] | 101 CT scans within 48 postoperative CTs | Lumen and ILT | PRAEVAorta 2D | ILT DSC = 0.848 ± 0.100, JAC = 0.747 ± 0.133 |

| Wang et al., 2022 [39] | 340 contrast-enhanced CTs of patients of infer-renal AAA with ILT from a single center | Lumen and ILT | DeepLabv3+-based DCNN model with ResNet-50 backbone 2D | ILT IOU = 0.8650 ± 0.0033 Mean IOU = 0.9078 ± 0.0029 |

| Wang et al., 2022 [40] | 340 contrast-enhanced CTs of patients of infer-renal AAA with ILT from a single center | Lumen and ILT | DeepLabv3+-based DCNN model with ResNet-50 backbone 2D | ILT IOU = 0.8650 ± 0.0033 Mean IOU = 0.9078 ± 0.0029 |

| Kongrat et al., 2022 [41] | 60 CTAs from a single center: 8 of normal subjects 14 of AAA patients 38 of AAA patients with thrombus | Lumen and ILT | 3D U-Net | ILT DSC = 0.9868 |

| Chandrashekar et al., 2022 [42] | 75 preoperative CTAs (284,624 CTA axial slices and 145,320 NCCT axial slices) | Aorta, lumen, and wall structure/ILT | 2D Attention-based U-Net | ILT DSC = 87.2 ± 6.3% |

| Chandrashekar et al., 2023 [43] | 75 patients with paired NCCTs and CTAs (11243 pairs of images); 200 independent cases with paired NCCTs and CTAs (29,468 pairs of images) | Lumen and ILT | 2D Attention-based U-Net | ACC = 0.935 |

| Mu et al., 2023 [44] | 70 CTA scans | Lumen and ILT | Context-aware cascaded U-Net integrated with a Residual 3D U-Net with an auto-context 3D U-Net structure using an auto-context mechanism 3D | ILT DSC = 0.804 Lumen DSC = 0.945 |

| Spinella et al., 2023 [45] | 73 thoraco-abdominal CTAs (48 AAAs, 25 healthy controls) from 11 scanners | Lumen and ILT | A pipeline including a U-Net structed localization and a 2.5D CNN combined with a multi-view integration approach 2D | ILT DSC = 0.93 |

| Kim et al., 2024 [46] | Prospective cohort of patients with AAA (Oxford Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Study) - 94 patients at 12 months - 79 patients at 24 months | Lumen, ILT, and calcification, | nnUnet, UNETR, and SwinUNETR tested 3D | 2D–3D U-Net ILT DSC = 0.782 ± 0.170 and HD95 = 11.616 ± 13.021mm |

| Lyu et al., 2024 [47] | 80 CTAs of AAA patients | ILT | Mixed-scale-driven Multiview perception network (M2Net) model 3D | ILT DSC = 0.884 ± 0.022, HD95 = 1.172 ± 0.493, IOU = 0.797 ± 0.034 |

| Robbi et al., 2025 [48] | Public dataset [49,50] Pipeline validation: 20 pre-CTAs from multiple datasets [49,51,52,53] | Lumen, ILT, calcification, and abdominal branches | BRAVE (Blood Vessels Recognition and Aneurysms Visualization Enhancement) including nnUnet for initial segmentation and SegResNet for the refinements 3D | AAA sac ILT DSC = 0.97 ± 0.03, HD = 4.52 ± 5.02 |

| Zhang et al., 2025 [54] | 63 CTAs of AAA patients from two scanners | Lumen and ILT | SDLU-Net 3D | ILT DSC = 0.828, HD95 = 17.330; Lumen DSC = 0.924, HD95 = 8.024 |

| Dataset Name | Number of Cases | Imaging Modality | Annotation Rule | ILT Annotation Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVT [52] | 56 volumes | CTA | Aorta only | No |

| Vascular Model Repository [51] | 91 volumes about aorta | CT/CTA/MRI/Ultrasound | Aorta only | No |

| TotalSegmentator [49] | 1204 volumes | CT | 104 anatomical structures (27 organs, 59 bones, 10 muscles, 8 vessels) | No |

| AortaSeg24 [66] | 100 volumes | CTA | 23 aortic branches and Society for Vascular Surgery/Society of Thoracic Surgeons zones | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, J.; Lareyre, F.; Goffart, S.; Chierici, A.; Delingette, H.; Raffort, J. Automatic Segmentation of Intraluminal Thrombus in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Based on CT Images: A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Methods. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8497. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238497

Guo J, Lareyre F, Goffart S, Chierici A, Delingette H, Raffort J. Automatic Segmentation of Intraluminal Thrombus in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Based on CT Images: A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Methods. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8497. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238497

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Jia, Fabien Lareyre, Sébastien Goffart, Andrea Chierici, Hervé Delingette, and Juliette Raffort. 2025. "Automatic Segmentation of Intraluminal Thrombus in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Based on CT Images: A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Methods" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8497. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238497

APA StyleGuo, J., Lareyre, F., Goffart, S., Chierici, A., Delingette, H., & Raffort, J. (2025). Automatic Segmentation of Intraluminal Thrombus in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Based on CT Images: A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Methods. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8497. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238497