Predictors of Postoperative Pneumonia Following Anatomical Lung Resections in Thoracic Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Analysis of the Risk Factors for Postoperative Pneumonia

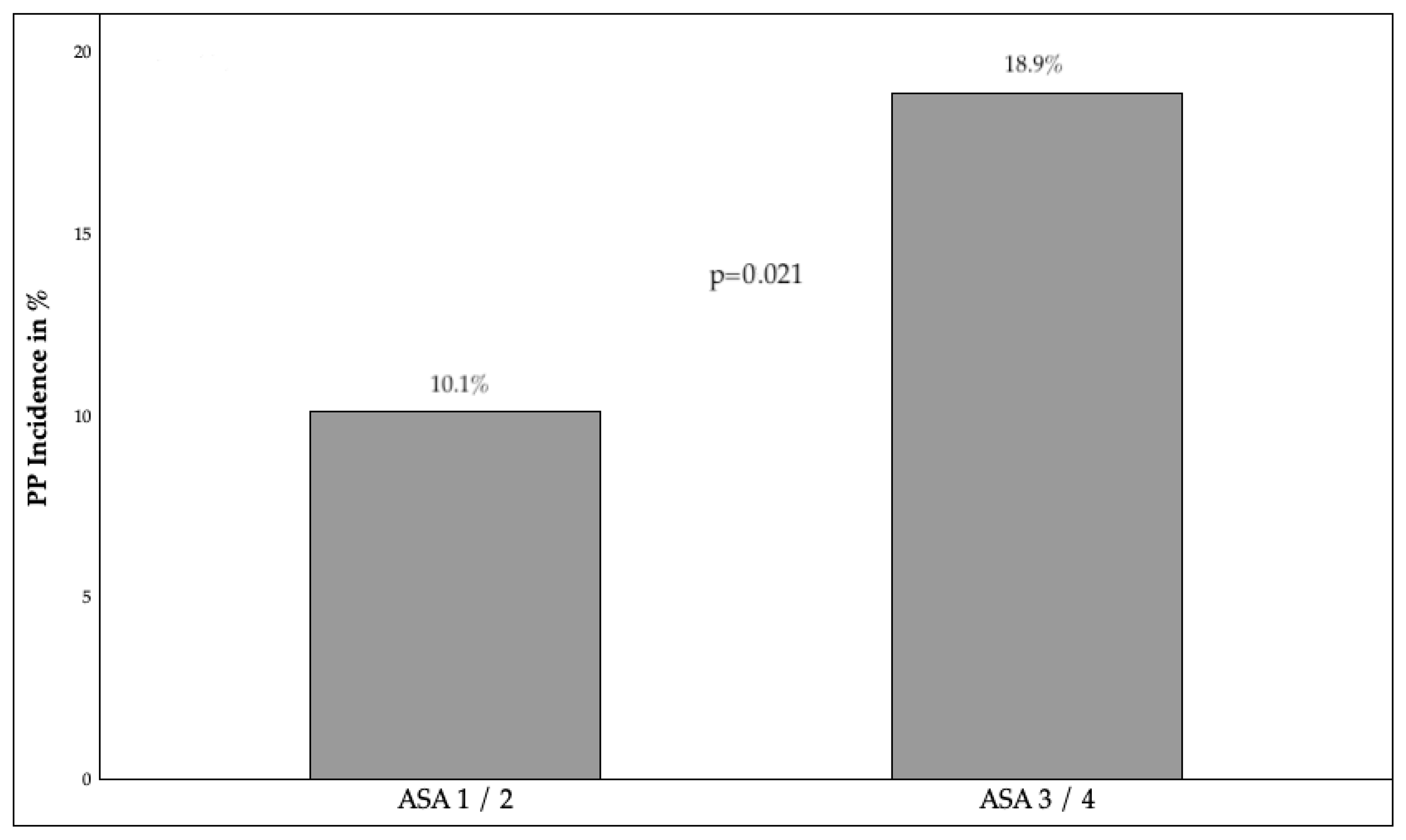

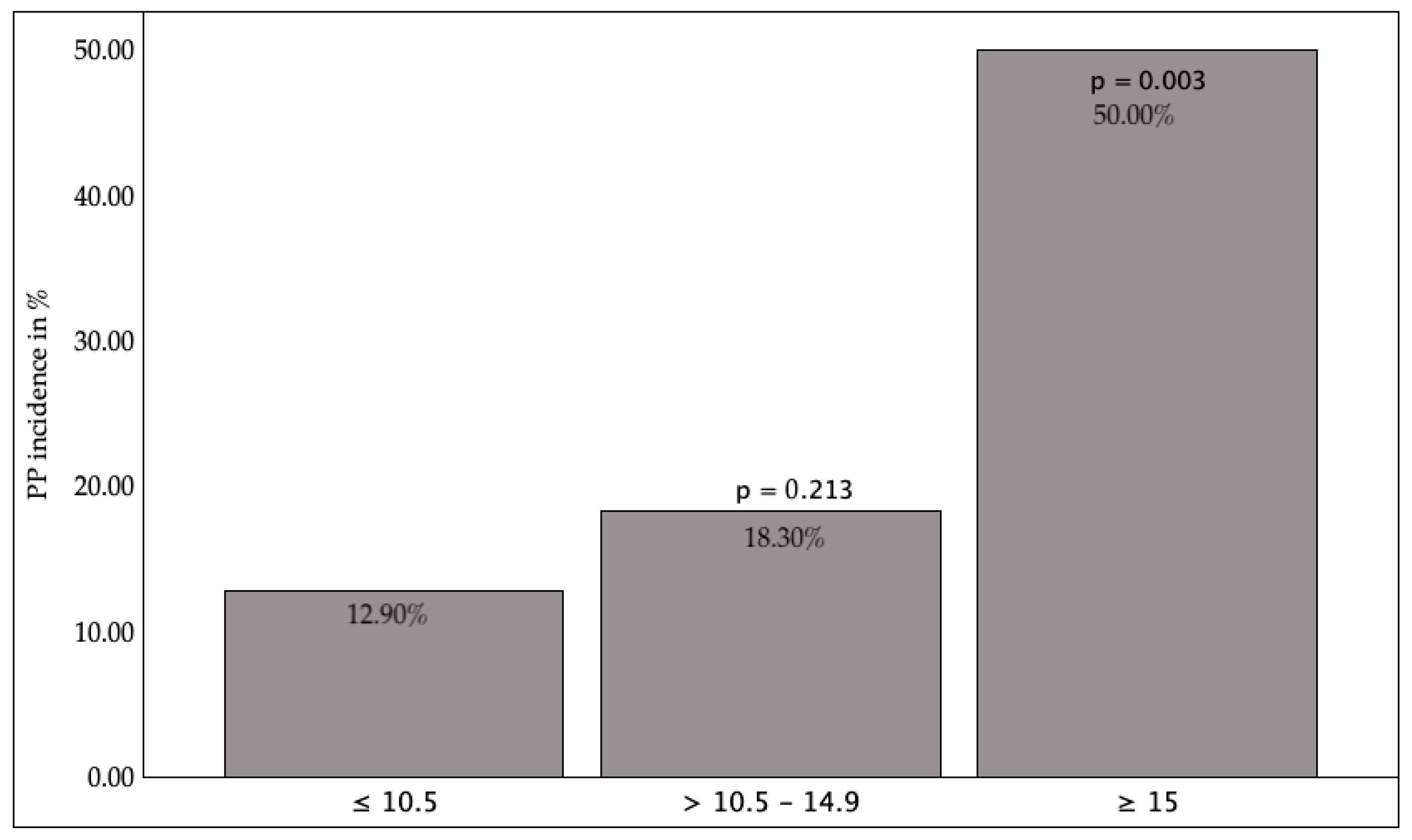

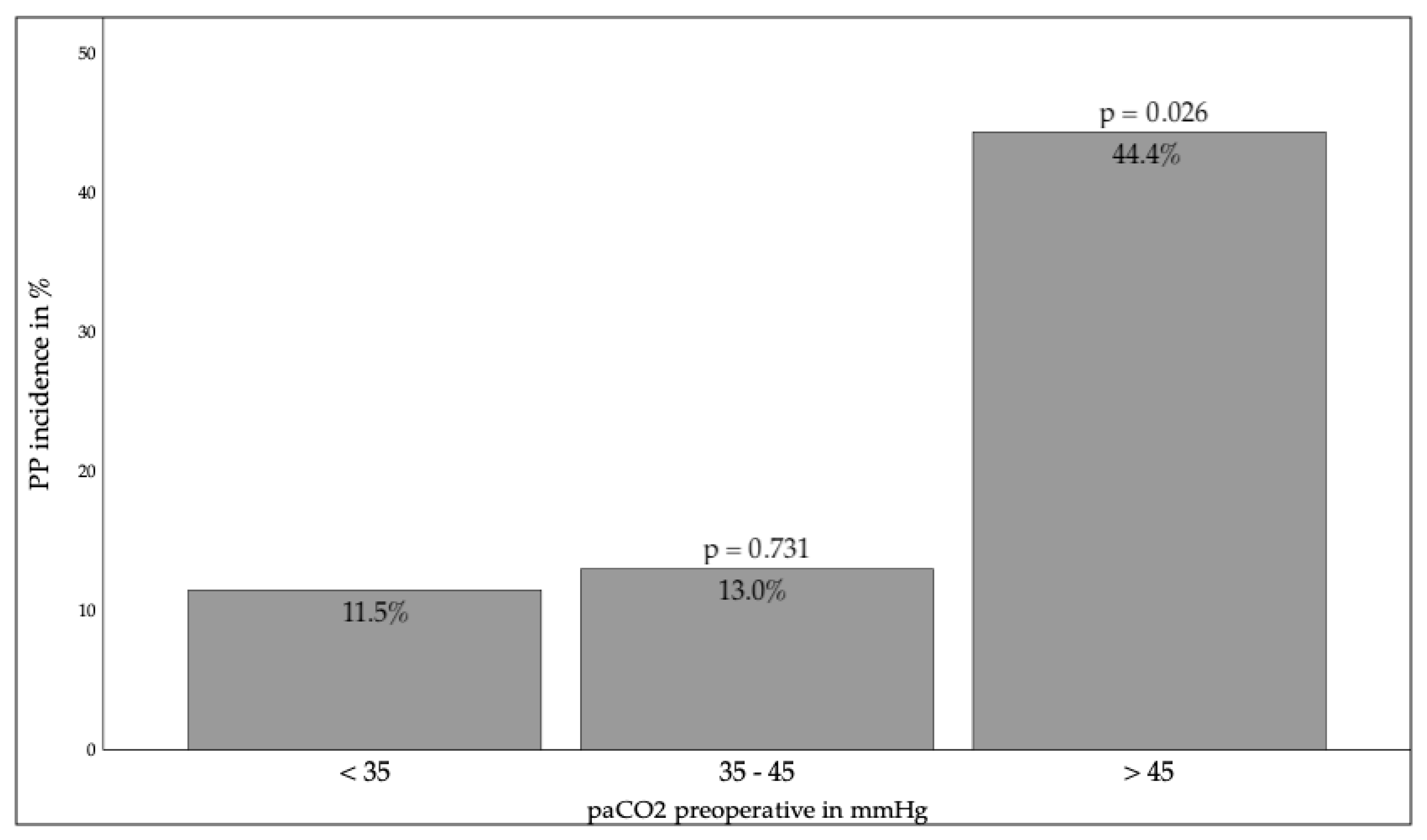

3.2.1. Preoperative Factors

3.2.2. Surgical Factors

3.2.3. Anesthesiologic Factors

3.2.4. Postoperative Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DLCO | Diffusion Capacity of the Lung for Carbon monoxide |

| EBUS-TBNA | Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration |

| ERAS: | Enhanced Recovery After Surgery |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in one second |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| GTR | German Thorax Register |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IMC | Intermediate Care Unit |

| KCO | Carbon Monoxide Transfer Coefficient |

| PCV | Pressure-Controlled Ventilation |

| PP | Postoperative Pneumonia |

| PPCs | Postoperative Pulmonary Complications |

| PVB | Paravertebral Block |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| THT | Thoracotomy |

| TNM | Tumor, Node, Metastasis |

| TEA | Thoracic Epidural Analgesia |

| UICC | Union for International Cancer Control |

| VATS | Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery |

| WBC | White Blood Cell Count |

References

- Sezen, A.I.; Sezen, C.B.; Yildirim, S.S.; Dizbay, M.; Ulutan, F. Cost Analysis and Evaluation of Risk Factors for Postoperative Pneumonia after Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery: A Single-Center Study. Curr. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenkovich, T.R.; Frederiksen, C.; Hudson, J.L.; Subramanian, M.; Kollef, M.H.; Patterson, G.A.; Kreisel, D.; Meyers, B.F.; Kozower, B.D.; Puri, V. Postoperative Pneumonia Prevention in Pulmonary Resections: A Feasibility Pilot Study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 107, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Huang, K.-Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, B.-Y.; Kor, C.-T.; Hou, M.-H.; Lin, S.-H. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery in Community-Acquired Thoracic Empyema: Analysis of Risk Factors for Mortality. Surg. Infect. 2022, 23, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, P.; Cieslik, H.; Rathinam, S.; Bishay, E.; Kalkat, M.S.; Rajesh, P.B.; Steyn, R.S.; Singh, S.; Naidu, B. Postoperative Pulmonary Complications Following Thoracic Surgery: Are There Any Modifiable Risk Factors? Thorax 2010, 65, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagne, F.; Guisier, F.; Venissac, N.; Baste, J.-M. The Role of Surgery in Lung Cancer Treatment: Present Indications and Future Perspectives—State of the Art. Cancers 2021, 13, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, A.L.; Senthil, P.; Keshwani, A.; McCleery, S.; Haridas, C.; Kumar, A.; Mathey-Andrews, C.; Martin, L.W.; Yang, C.-F.J. Long-Term Survival After Lung Cancer Resection in the National Lung Screening Trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2024, 117, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie. S3-Leitlinie Lungenkarzinom, Version 4.0. 2025. Available online: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/020-007OLm_S3_Praevention-Diagnostik-Therapie-Nachsorge-Lungenkarzinom_2025-04_01.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Starke, H.; von Dossow, V.; Karsten, J. Preoperative Evaluation in Thoracic Surgery: Limits of the Patient’s Functional Operability and Consequence for Perioperative Anaesthesiologic Management. Curr. Opin. Anesthesiol. 2022, 35, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.A.; Makary, M.A.; Dorman, T.; Pronovost, P.J. Clinical and Economic Outcomes of Hospital Acquired Pneumonia in Intra-Abdominal Surgery Patients. Ann. Surg. 2006, 243, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.; Kumar, S.; Anstee, C.; Gingrich, M.; Simone, A.; Ahmadzai, Z.; Thavorn, K.; Seely, A. Index Hospital Cost of Adverse Events Following Thoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Economic Literature. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.-Z.; Cai, L.-L.; Hu, W.-W.; Lian, L.-R.; Meng, W.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.-L.; Yao, X.-J.; Pan, H.-D.; Liu, L.; et al. Predicting and Managing Postoperative Pneumonia in Thoracic Surgery Patients: The Role of Age, Cancer Type, and Risk Factors. Ageing Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 1, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, S.; Shimomura, M.; Tsunezuka, H.; Teramukai, S.; Ishihara, S.; Shimada, J.; Inoue, M. Prognostic Significance of Perioperative C-Reactive Protein in Resected Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 32, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker, R.M.; Osmundson, E.C. Identification of Clinical Predictors of Benefit of Palliative Thoracic Radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 111, e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetmahajan, M.; Ranganathan, P.; Parab, S.; Unnithan, M. Retrospective observational study of perioperative anaesthesia management and outcomes in patients undergoing pneumonectomy for lung cancer in a tertiary care cancer centre. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2023, 37, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.S.; Hucklenbruch, C.; Gurka, K.K.; Scalzo, D.C.; Wang, X.-Q.; Jones, D.R.; Tanner, S.R.; Jaeger, J.M. Intraoperative Factors and the Risk of Respiratory Complications After Pneumonectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 92, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde, Y.; Argawi, A.; Alemayehu, Y.; Desalegn, M.; Samuel, S. The Prevalence and Associated Factors of Intraoperative Hypotension Following Thoracic Surgery in Resources Limited Area, 2023: Multicentre Approach. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 6989–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, P.; Brenner, B.; Tsang, S.; Elkassabany, N.; Martin, L.W.; Carrott, P.; Scott, C.; Mazzeffi, M. Anesthetic Technique and Postoperative Pulmonary Complications (PPC) after Video Assisted Thoracic (VATS) Lobectomy: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, J.; Domingues, D.M.; Chan, J.; Zamvar, V. Open Thoracotomy versus VATS versus RATS for Segmentectomy: A Systematic Review & Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 19, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freystaetter, K.; Waterhouse, B.R.; Chilvers, N.; Trevis, J.; Ferguson, J.; Paul, I.; Dunning, J. The Importance of Culture Change Associated With Novel Surgical Approaches and Innovation: Does Perioperative Care Transcend Technical Considerations for Pulmonary Lobectomy? Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 597410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, T.J.P.; Rasburn, N.J.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Brunelli, A.; Cerfolio, R.J.; Gonzalez, M.; Ljungqvist, O.; Petersen, R.H.; Popescu, W.M.; Slinger, P.D.; et al. Guidelines for Enhanced Recovery after Lung Surgery: Recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lai, Y.; Li, P.; Su, J.; Che, G. Influence of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) on Patients Receiving Lung Resection: A Retrospective Study of 1749 Cases. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, M.; Blaj, M.; Ristescu, A.I.; Iosep, G.; Avădanei, A.-N.; Iosep, D.-G.; Crișan-Dabija, R.; Ciocan, A.; Perțea, M.; Manciuc, C.D.; et al. Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: A Literature Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporta, M.L.; Kruthiventi, S.C.; Mantilla, C.B.; Johnson, R.L.; Sprung, J.; Portner, E.R.; Schroeder, D.R.; Weingarten, T.N. Three Risk Stratification Tools and Postoperative Pneumonia After Noncardiothoracic Surgery. Am. Surg. 2021, 87, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, N.J.; De Oliveira, G.S.; Jain, U.K.; Kim, J.Y.S. ASA Class Is a Reliable Independent Predictor of Medical Complications and Mortality Following Surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 18, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Dong, M.; Hong, G.; Agrafiotis, A.C.; Patel, A.J.; Ding, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, J. Seven Preoperative Factors Have Strong Predictive Value for Postoperative Pneumonia in Patients Undergoing Thoracoscopic Lung Cancer Surgery. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 2193–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Pastorini, A.; Riedel, R.; Koryllos, A.; Beckers, F.; Ludwig, C.; Stoelben, E. The Impact of Preoperative Elevated Serum C-Reactive Protein on Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality after Anatomic Resection for Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2017, 109, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, E.; Knio, Z.O.; Mahmood, F.; Amir, R.; Shahul, S.; Mahmood, B.; Baribeau, Y.; Mueller, A.; Matyal, R. Preoperative Asymptomatic Leukocytosis and Postoperative Outcome in Cardiac Surgery Patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.T. Smoking and Pulmonary Complications: Respiratory Prehabilitation. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, S639–S644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, T.; Shoji, F.; Tagawa, T.; Kinoshita, F.; Haratake, N.; Edagawa, M.; Yamazaki, K.; Takenoyama, M.; Takeo, S.; Mori, M. Does Short-Term Cessation of Smoking before Lung Resections Reduce the Risk of Complications? J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 7127–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, J.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Tian, H. Timing Effects of Short-Term Smoking Cessation on Lung Cancer Postoperative Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 22, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancın, B.; Uysal, S.; Kumbasar, U.; Dikmen, E.; Doğan, R. Risk Factors for Postoperative Pneumonia in Patients Undergoing Resection for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Pneumon 2023, 36, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ameri, M.; Bergman, P.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Sartipy, U. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic versus Open Thoracotomy Lobectomy: A Swedish Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 3499–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, F.; Re Cecconi, E.; Vanni, G.; Ambrogi, V. Postoperative Pneumonia in the Era of Minimally-Invasive Thoracic Surgery: A Narrative Review. Video-Assist. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Zhong, Y.; Deng, J.; She, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, J.; Jiang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, C. Comparison of Uniportal Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic versus Thoracotomy Bronchial Sleeve Lobectomy with Pulmonary Arterioplasty for Centrally Located Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2020, 59, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, P.M.; Karim, S.O.; Sofi, H.A.; Fuad, F.E.; Kakamad, S.H.; Abdullah, H.O.; Abdalla, B.A.; Hussein, S.M.; Rahim, H.M.; Hassan, M.N.; et al. Uniport Versus Multiport Video Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS): Comparisons and Outcomes: A Review Article. Barw. Med. J. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re Cecconi, E.; Mangiameli, G.; De Simone, M.; Cioffi, U.; Marulli, G.; Testori, A. Vats Lobectomy for Lung Cancer. What Has Been the Evolution over the Time? Front. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1268362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matache, S.R.; Afetelor, A.A.; Voinea, A.M.; Cosoveanu, G.C.; Dumitru, S.-M.; Alexe, M.; Orghidan, M.; Smaranda, A.M.; Dobrea, V.C.; Șerbănoiu, A.; et al. Balancing Accuracy, Safety, and Cost in Mediastinal Diagnostics: A Systematic Review of EBUS and Mediastinoscopy in NSCLC. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, G.; Lu, B.; Li, X. The Relationship between the Duration of Surgery for Thoracoscopic Lobectomy and Postoperative Complications in Patients with Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2024, 95, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Miao, Q.; Wu, J. A Review of Intraoperative Protective Ventilation. Anesthesiol. Perioper. Sci. 2024, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Tan, Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, G.; Situ, D.; Lin, Y.; Su, X.; Liu, Q.; Rong, T. Thoracoscopic Surgery Versus Thoracotomy for Lung Cancer: Short-Term Outcomes of a Randomized Trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 105, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, X.-J.; Shi, L.; Li, F.-Y.; Lin, N.-M. Risk Factors of Postoperative Nosocomial Pneumonia in Stage I-IIIa Lung Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 3071–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ASA | ICU | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 22.2% | 0.012 |

| 3–4 | 34.2% | |

| Surgery | ICU | p-Value |

| Pneumonectomy | 93.3% | <0.001 |

| Bilobectomy Lobectomy Segment resection | 76.9% 29.8% 12.8% | <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 |

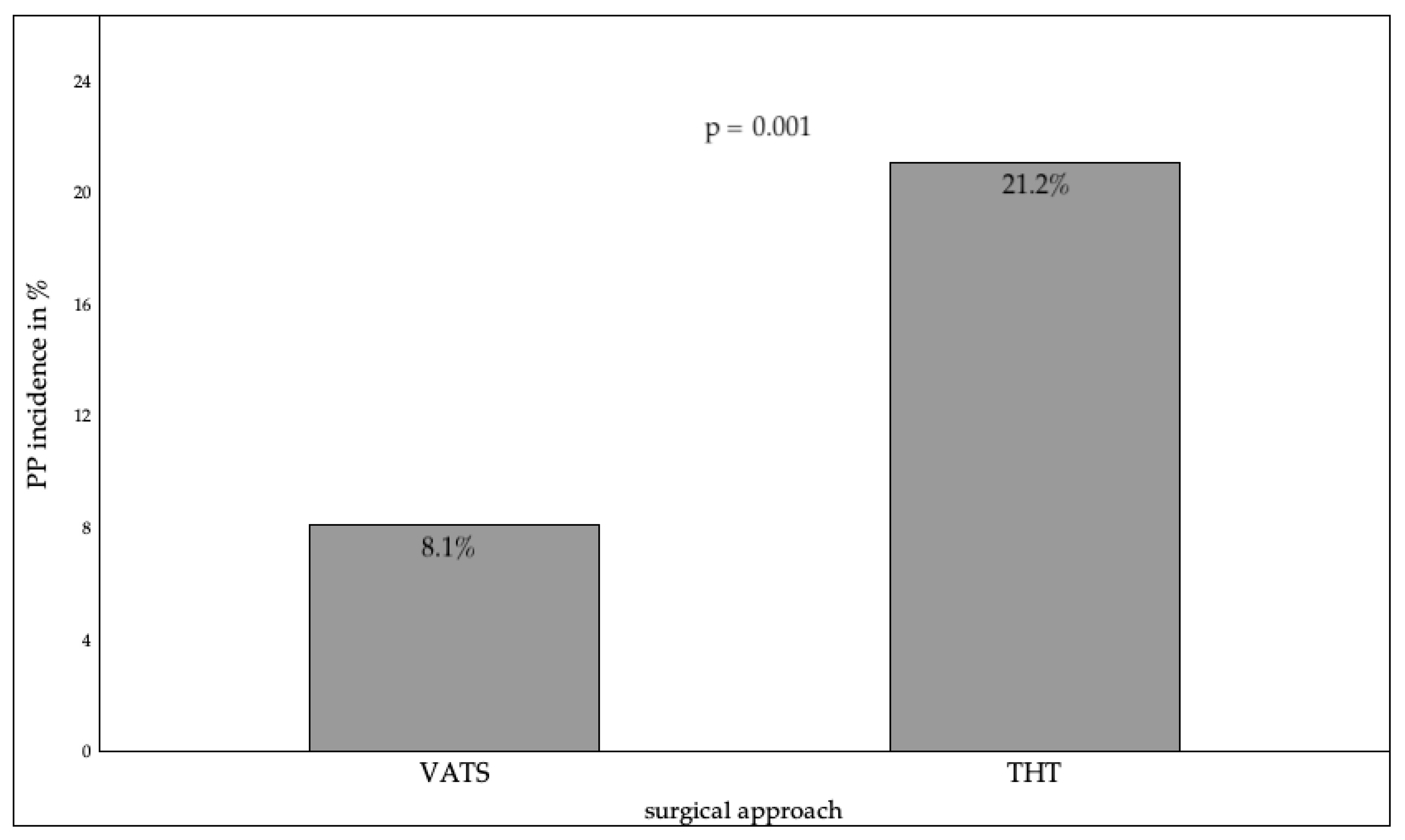

| Operative access route | ICU | p-Value |

| VATS | 9.2% | <0.001 |

| THT | 45.7% | <0.001 |

| Anesthetic Form | PP | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| TIVA | 17.2% | 0.252 |

| balanced anesthesia pure general anesthesia combination process (+TEA/PVB) TEA PVB (Single Shot) | 12.6% 13.0% 18.2% 14.3% 18.4% | 0.252 0.195 0.195 0.785 0.785 |

| Anesthetic form (THT only) | PP | p-Value |

| pure general anesthesia | 43.2% | 0.862 |

| combination process (+TEA/PVB) | 56.8% | |

| Double lumen tube | PP | p-Value |

| Left | 14.9% | 0.803 |

| right | 17.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schnabel, T.M.; Kutun, K.K.; Linde, M.; Defosse, J.; Gerbershagen, M.U. Predictors of Postoperative Pneumonia Following Anatomical Lung Resections in Thoracic Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238445

Schnabel TM, Kutun KK, Linde M, Defosse J, Gerbershagen MU. Predictors of Postoperative Pneumonia Following Anatomical Lung Resections in Thoracic Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238445

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchnabel, Timon Marvin, Kim Karen Kutun, Martin Linde, Jerome Defosse, and Mark Ulrich Gerbershagen. 2025. "Predictors of Postoperative Pneumonia Following Anatomical Lung Resections in Thoracic Surgery" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238445

APA StyleSchnabel, T. M., Kutun, K. K., Linde, M., Defosse, J., & Gerbershagen, M. U. (2025). Predictors of Postoperative Pneumonia Following Anatomical Lung Resections in Thoracic Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238445