Congenital Scoliosis: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Surgical Decision-Making in Pediatric Spinal Deformity—An Expanded Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Epidemiology and Associated Anomalies

3.1. Incidence and Population Burden

3.2. Genetic and Developmental Factors

4. Pathophysiology and Classification

4.1. Embryological Development and Malformation Patterns

4.2. Growth Patterns and Progression Risk

5. Clinical Presentation and Assessment

5.1. Early Diagnosis of CS

5.2. Physical Examination and Clinical Features

5.3. Associated Anomalies and Syndromic Conditions

6. Diagnostic Imaging and Assessment

6.1. Radiographic Evaluation

6.2. Advanced Imaging Modalities

6.3. Functional Assessment

7. Treatment Options and Decision-Making

7.1. Observation and Non-Surgical Management

7.2. Surgical Timing and Strategy

7.3. Surgical Techniques

7.3.1. Convex Growth Arrest and Epiphysiodesis

7.3.2. In Situ Fusion

7.3.3. Hemivertebrectomy

7.3.4. Growing Rod Systems

7.3.5. Impact on Pulmonary Development and Vertical Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Rib (VEPTR)

7.3.6. Growth Guidance Systems—Shilla

7.3.7. Posterior Vertebral Column Resection (PVCR)

8. Complications and Risk Management

8.1. Surgical Complications

8.2. Long-Term Complications

9. Outcomes and Prognosis

10. Future Directions and Innovations

10.1. Genetic Therapy and Regenerative Medicine

10.2. Technological Innovations

11. Limitations of the Literature

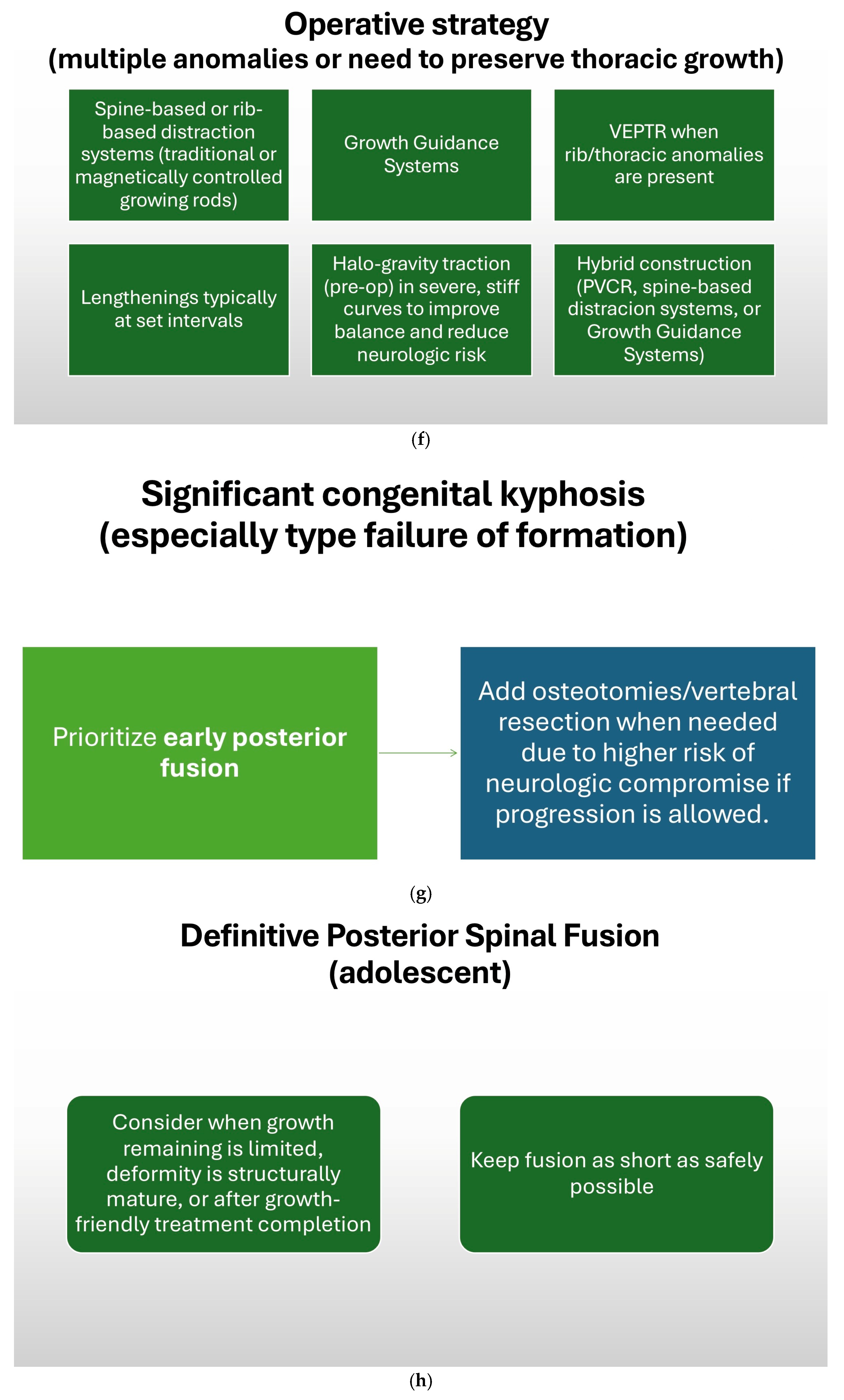

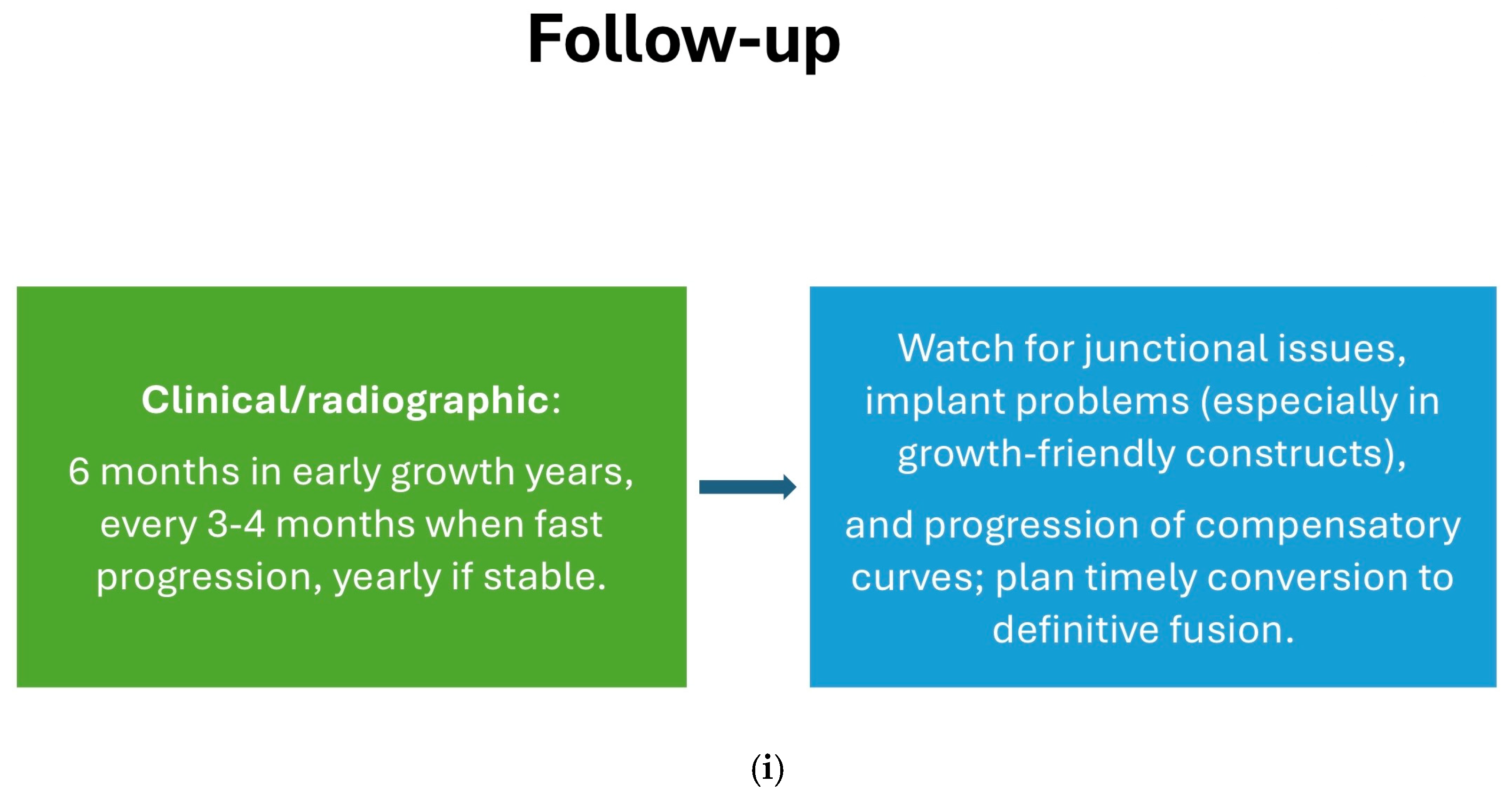

12. Treatment Algorithm

13. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMaster, M.J.; Ohtsuka, K. The natural history of congenital scoliosis: A study of two hundred and fifty-one patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1982, 64, 1128–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, K.M.; Spivak, J.M.; Bendo, J.A. Embryology of the spine and associated congenital abnormalities. Spine J. 2005, 5, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahys, J.M.; Guille, J.T. What’s new in congenital scoliosis? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2018, 38, e172–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne-Davies, R. Congenital vertebral anomalies: Aetiology and relationship to spina bifida cystica. J. Med. Genet. 1975, 12, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.M., Jr.; Smith, M.D.; Mayes, T.C.; Mangos, J.A.; Willey-Courand, D.B.; Kose, N.; Pinero, R.F.; Alder, M.E.; Duong, H.L.; Surber, J.L. The characteristics of thoracic insufficiency syndrome associated with fused ribs and congenital scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2003, 85, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Piantoni, L.; Tello, C.A.; Remondino, R.G.; Galaretto, E.; Falconi, B.A.; Noel, M.A. Hemivertebra resection in small children: A literature review. Glob. Spine J. 2023, 13, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passias, P.G.; Poorman, G.W.; Jalai, C.M.; Diebo, B.G.; Vira, S.; Horn, S.R.; Baker, J.F.; Shenoy, K.; Hasan, S.; Buza, J.; et al. Incidence of congenital spinal abnormalities among pediatric patients and their association with scoliosis and systemic anomalies. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e608–e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, Y. Surgical technique for one-stage posterior hemivertebrectomy. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2024, 110, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollini, G.; Docquier, P.L.; Viehweger, E.; Launay, F.; Jouve, J.L. Lumbar hemivertebra resection. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.A.; Ge, D.H.; Boden, E.; Hanstein, R.; Alvandi, L.M.; Lo, Y.; Hwang, S.; Samdani, A.F.; Sponseller, P.D.; Garg, S.; et al. Posterior-only resection of single hemivertebrae with 2-level versus >2-level fusion: Can we improve outcomes? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2022, 42, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Kou, I.; Mizumoto, S.; Yamada, S.; Kawakami, N.; Nakajima, M.; Otomo, N.; Ogura, Y.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N.; et al. Screening of known disease genes in congenital scoliosis. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2018, 6, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, P.F.; Raggio, C.L.; Blank, R.D.; McCarty, C.; Broeckel, U.; Pickart, M.A. Clinical, genetic and environmental factors associated with congenital vertebral malformations. Mol. Syndromol. 2013, 4, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.C. Examination of the newborn with congenital scoliosis. Adv. Neonatal Care 2008, 8, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, J.; Nikkinen, H.; Keikkala, E.; Mustaniemi, S.; Gissler, M.; Laivuori, H.; Eriksson, J.G.; Kaaja, R.; Pouta, A.; Kajantie, E.; et al. Gestational diabetes is associated with the risk of offspring’s congenital anomalies: A register-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Shepard, N.; Arlet, V. The etiology of congenital scoliosis: Genetic vs. environmental—A report of three monozygotic twin cases. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, P.F.; Dunwoodie, S.L.; Kusumi, K.; Pourquié, O.; Tassy, O.; Offiah, A.C.; Cornier, A.S.; Alman, B.A.; Blank, R.D.; Raggio, C.L.; et al. Molecular diagnosis of vertebral segmentation disorders in humans. Expert Opin. Med. Diagn. 2008, 2, 1107–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackel, C.E.; Jada, A.; Samdani, A.F.; Stephen, J.H.; Bennett, J.T.; Baaj, A.A.; Hwang, S.W. A comprehensive review of the diagnosis and management of congenital scoliosis. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2018, 34, 2155–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiță, R.A.; Georgescu, I.; Muntean, M.L.; Hamei, Ș.; Japie, E.M.; Dughilă, C.; Țiripa, I. Burnei-Gavriliu classification of congenital scoliosis. J. Med. Life 2015, 8, 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Giampietro, P.F.; Pourquie, O.; Raggio, C.; Ikegawa, S.; Turnpenny, P.D.; Gray, R.; Dunwoodie, S.L.; Gurnett, C.A.; Alman, B.; Cheung, K.; et al. Summary of the first inaugural joint meeting of the International Consortium for Scoliosis Genetics and the International Consortium for Vertebral Anomalies and Scoliosis, March 16–18, 2017, Dallas, Texas. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2018, 176, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, P.F.; Dunwoodie, S.L.; Kusumi, K.; Pourquié, O.; Tassy, O.; Offiah, A.C.; Cornier, A.S.; Alman, B.A.; Blank, R.D.; Raggio, C.L.; et al. Progress in the understanding of the genetic etiology of vertebral segmentation disorders in humans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1151, 38–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.; Megas, A.; Mandalapu, A.; Haddas, R.; Mesfin, A. Radiographic and clinical findings associated with Klippel-Feil syndrome: A case series. Spine Deform. 2025, 13, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirikos, A.I.; McMaster, M.J. Congenital anomalies of the ribs and chest wall associated with congenital deformities of the spine. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2003, 85, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, B.; Yan, H.; Tang, J. A review of the hemivertebrae and hemivertebra resection. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 36, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, N.; Tsuji, T.; Imagama, S.; Lenke, L.G.; Puno, R.M.; Kuklo, T.R. Classification of congenital scoliosis and kyphosis. Spine 2009, 34, 1756–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Rajasekaran, S.; Balamurali, G.; Shetty, A. Vertebral and intraspinal anomalies in Indian population with congenital scoliosis: A study of 119 consecutive patients. Asian Spine J. 2016, 10, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, M.J.; Singh, H. Natural history of congenital kyphosis and kyphoscoliosis: A study of one hundred and twelve patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1999, 81, 1367–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Kai, S.; Yong-Gang, Z.; Guo-Quan, Z.; Tian-Xiang, D. Relationship between lung volume and pulmonary function in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Computed tomographic-based 3-dimensional volumetric reconstruction of lung parenchyma. Clin. Spine Surg. 2016, 29, E396–E400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.W.; Sarwark, J.F.; Vora, A.; Huang, B.K. Evaluating congenital spine deformities for intraspinal anomalies with magnetic resonance imaging. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2001, 21, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sucato, D.J. Surgical treatment of congenital scoliosis and kyphosis in pediatric patients. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 38, 419–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hedequist, D.J. Congenital scoliosis. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2007, 15, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tan, H.; Bi, J.; Li, Z.; Rong, T.; Lin, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, X.; Shen, J. Identification of competing endogenous RNA regulatory networks in vitamin A deficiency-induced congenital scoliosis by transcriptome sequencing analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 2134–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Goethem, J.; Van Campenhout, A.; van den Hauwe, L.; Parizel, P.M. Scoliosis. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2007, 17, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furumoto, T.; Miura, N.; Akasaka, T.; Mizutani-Koseki, Y.; Sudo, H.; Fukuda, K.; Maekawa, M.; Yuasa, S.; Fu, Y.; Moriya, H.; et al. Notochord-dependent expression of MFH1 and PAX1 cooperates to maintain the proliferation of sclerotome cells during the vertebral column development. Dev. Biol. 1999, 210, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Turnpenny, P.D.; Ellard, S. Alagille syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 20, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnei, G.; Gavriliu, S.; Vlad, C.; Georgescu, I.; Ghita, R.A.; Dughilă, C.; Japie, E.M.; Onilă, A. Congenital scoliosis: An up-to-date. J. Med. Life 2015, 8, 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Kong, X.; Jia, Y.; Jia, Y.; Ou, W.; Dai, C.; Li, G.; Gao, R. An overview of PAX1: Expression, function and regulation in development and diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1051102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sheu, T.; Dong, Y.; Hoak, D.M.; Zuscik, M.J.; Schwarz, E.M.; Hilton, M.J.; O’Keefe, R.J.; Jonason, J.H. TAK1 regulates SOX9 expression in chondrocytes and is essential for postnatal development of the growth plate and articular cartilages. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 5704–5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, D.; Wohler, E.; Erfani, V.; Li, G.; Aguilera, A.N.; Santiago-Cornier, A.; Zhao, S.; Hwang, S.W.; Steiner, R.D.; Zhang, T.J.; et al. COL11A2 as a candidate gene for vertebral malformations and congenital scoliosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 2913–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Berry-Wynne, K.M.; Asai-Coakwell, M.; Sundaresan, P.; Footz, T.; French, C.R.; Abitbol, M.; Fleisch, V.C.; Corbett, N.; Allison, W.T.; et al. Mutation of the bone morphogenetic protein GDF3 causes ocular and skeletal anomalies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 19, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, G.; Huang, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Identification of novel FBN1 variations implicated in congenital scoliosis. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 65, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, N.L.; McLennan, A.; Silva, R.C.; Hosek, K.; Liu, Y.C. Vertebral anomalies in microtia patients at a tertiary pediatric care center. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023, 169, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, S.; Ahuja, S. Congenital scoliosis: Management and future directions. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2008, 74, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, M.J.; McMaster, M.E. Prognosis for congenital scoliosis due to a unilateral failure of vertebral segmentation. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2013, 95, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furdock, R.; Brouillet, K.; Luhmann, S.J. Organ system anomalies associated with congenital scoliosis: A retrospective study of 305 patients. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e190–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.S.; Modi, H.N.; Srinivasalu, S.; Chen, T.; Suh, S.W.; Yang, J.H.; Song, H.R. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of Cobb angle measurement: Endplate versus pedicle as bony landmarks for measurement: A statistical analysis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2009, 29, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, S.; Chung, U.; Ohba, S.; Hojo, H. Understanding paraxial mesoderm development and sclerotome specification for skeletal repair. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, N.; Aoyama, H. Dermomyotomal origin of the ribs as revealed by extirpation and transplantation experiments in chick and quail embryos. Development 1998, 125, 3437–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.M.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Patterning of mammalian somites by surface ectoderm and notochord: Evidence for sclerotome induction by a hedgehog homolog. Cell 1994, 79, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.L.; Laufer, E.; Riddle, R.D.; Tabin, C. Ectopic expression of sonic hedgehog alters dorsal-ventral patterning of somites. Cell 1994, 79, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Tuan, R.S. Functional involvement of Pax-1 in somite development: Somite dysmorphogenesis in chick embryos treated with Pax-1 paired-box antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. Teratology 1995, 52, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.N.; Green, J.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Qiao, M.; Peabody, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, J.; Yan, Z.; Denduluri, S.; et al. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes. Dis. 2014, 1, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessel, M.; Gruss, P. Murine developmental control genes. Science 1990, 249, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leatherman, K.D.; Dickson, R.A. Two-stage corrective surgery for congenital deformities of the spine. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1979, 61, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Surgical outcomes of hemivertebra resection with mono-segment fusion in children under 10 years with congenital scoliosis: A retrospective study stratified by the crankshaft phenomenon. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025, 26, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Predictive modeling and long-term outcomes in optimizing fusion strategies for congenital scoliosis: A retrospective analysis of posterior hemivertebra resection. Int. Orthop. 2025, 49, 2195–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, N.; Saito, T.; Kawakami, K.; Tauchi, R. Coupling Failure as the Forth Category in the Classification of Congenital Spinal Deformity. Sci. Repos. 2018, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- MacEwen, G.D.; Winter, R.B.; Hardy, J.H. Evaluation of kidney anomalies in congenital scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1972, 54, 1451–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurusamy, T.; Abdul Manan, M.F.B.; Amir, D.; Mohamad, F. Triple-rod construct approach for severe rigid scoliosis: A comprehensive case series. Cureus 2025, 17, e81546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.B.; Leonard, A.S.; Smith, D.E. Congenital Deformities of the Spine; Thieme-Stratton Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1983; ISBN 9780865770799. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, P.S.; Seiden, A.M.; Smith, T.L. Surgical management of adult inferior turbinate hypertrophy: A systematic review of the evidence. Laryngoscope 2009, 119, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, T.; Jiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Feng, E.; Sun, H.; Zhao, J.; Shen, J. Morphological analysis of isolated hemivertebra: Radiographic manifestations related to the severity of congenital scoliosis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspiris, A.; Grivas, T.B.; Weiss, H.R.; Turnbull, D. Surgical and conservative treatment of patients with congenital scoliosis: A search for long-term results. Scoliosis 2011, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, R.J.; Stilling, F.H.; Stell, H.H. Progression of congenital scoliosis due to hemivertebrae and hemivertebrae with bars. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1975, 57, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, H.; Safari, N.; Sharifi, R.; Ostadrahimi, N.; Ahmad, A. The role of 3D printed spine model in complex spinal deformity surgery: An experience with a case, technical notes and review of the literature. Clin. Case Rep. 2025, 13, e70675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Guo, X.; Zhu, H.; Zou, Y.; Wu, M.; Meng, Z. Analysis of the factors affecting the loss of correction effect in patients with congenital scoliosis after one-stage posterior hemivertebrae resection and orthosis fusion. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023, 24, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yin, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhang, J. Pelvic obliquity: A possible risk factor for curve progression after lumbosacral hemivertebra resection with short segmental fusion. J. Bone Jt. Surg Am. 2025, 107, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Mao, S. Analysis of the hemivertebra resection strategy in adolescent and young adult congenital scoliosis caused by double hemivertebrae. Spine Deform. 2025, 13, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzumcugil, A.; Cil, A.; Yazici, M.; Acaroglu, E.; Alanay, A.; Aksoy, C.; Surat, A. Convex growth arrest in the treatment of congenital spinal deformities, revisited. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2004, 24, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, H.W.D.; Tan, K.A.; Thadani, V.N.; Liu, G.K.; Wong, H.K. Characterization of sagittal spine alignment with reference to the gravity line and vertebral slopes: An analysis of different Roussouly curves. Spine 2020, 45, E481–E488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, X. Evolution of the postoperative sagittal spinal profile in early-onset scoliosis: Is there a difference between rib-based and spine-based growth-friendly instrumentation? J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2017, 20, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlet, V.; Odent, T.; Aebi, M. Congenital scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2003, 12, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhns, J.G.; Hormell, R.S. Management of congenital scoliosis; review of one hundred seventy cases. AMA Arch. Surg. 1952, 65, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.B. Congenital spinal deformity: Natural history and treatment. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1983, 176, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shengru, W.; Qiu, G.; Wang, Y.; Weng, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, S. The efficacy and complications of posterior hemivertebra resection. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hell, A.K.; Campbell, R.M.; Hefti, F. The vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib implant for the treatment of thoracic insufficiency syndrome associated with congenital and neuromuscular scoliosis in young children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2005, 14, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemme, W.R.; Denis, F.; Winter, R.B.; Lonstein, J.E.; Koop, S.E. Spinal instrumentation without fusion for progressive scoliosis in young children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2001, 21, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yan, F.; Du, L.; Qin, L. A novel portable and radiation-free method for assessing scoliosis: An accurate and reproducible study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Yang, J.; Sha, L.; Yang, J. Factors that influence in-brace derotation effects in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A study based on EOS imaging system. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.U.; Park, W.T.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, G.W. Diagnostic technology for spine pathology. Asian Spine J. 2022, 16, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, C.H.; Kalen, V. Three-dimensional computed tomography in the assessment of congenital scoliosis. Skelet. Radiol. 1999, 28, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahinski, J.R.; Polly, D.W.; McHale, K.A.; Ellenbogen, R.G. Occult intraspinal anomalies in congenital scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2000, 20, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEwen, G.D.; Winter, R.B.; Hardy, J.H.; Sherk, H.H. Evaluation of kidney anomalies in congenital scoliosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 434, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drvaric, D.M.; Ruderman, R.J.; Conrad, R.W.; Grossman, H.; Webster, G.D.; Schmitt, E.W. Congenital scoliosis and urinary tract abnormalities: Are intravenous pyelograms necessary? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1987, 7, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, M.G.; Matsumoto, H.; Bye, M.R.; Gomez, J.A.; Booker, W.A.; Hyman, J.E.; Warren, L.J.; Roye, D.P., Jr. A retrospective cohort study of pulmonary function, radiographic measures, and quality of life in children with congenital scoliosis: An evaluation of patient outcomes after early spinal fusion. Spine 2008, 33, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, H.; Heiskanen, S.; Syvänen, J.; Raitio, A.; Helenius, L.; Ahonen, M.; Diarbakerli, E.; Gerdhem, P.; Helenius, I. Surgical and health-related quality of life outcomes in children with congenital scoliosis during 5-year follow-up. Comparison to age and sex-matched healthy controls. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2023, 43, e451–e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.G.; Matsumoto, H.; Roye, D.P., Jr.; Gomez, J.A.; Betz, R.R.; Emans, J.B.; Glotzbecker, M.P.; Spence, D.D.; Hresko, M.T. Health-related quality of life in children with thoracic insufficiency syndrome. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2006, 26, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, P.; Grabala, P.; Gupta, M.C.; Pereira, D.E.; Latalski, M.; Danielewicz, A.; Grabala, M.; Tomaszewski, M.; Kotwicki, T. Complications and health-related quality of life in children with various etiologies of early-onset scoliosis treated with magnetically controlled growing rods: A multicenter study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.J.; ElNemer, W.; Sponseller, P.D. How can we predict dominant compensatory curves in congenital scoliosis? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughenbury, P.; Tsirikos, A.I. Current concepts in the treatment of neuromuscular scoliosis: Clinical assessment, treatment options, and surgical outcomes. Bone Jt. Open 2022, 3, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P.; Helenius, I.J.; Kowalski, P.; Grabala, M.; Zacha, S.; Deszczynski, J.M.; Albrewczynski, T.; Galgano, M.A.; Buchowski, J.M.; Chamberlin, K.; et al. The child’s age and the size of the curvature do not affect the accuracy of screw placement with the free-hand technique in spinal deformities in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Márquez, J.M.; Pizones, J.; Martín-Buitrago, M.P.; Fernández-Baillo, N.; Pérez-Grueso, F.J. Midterm results of hemivertebrae resection and transpedicular short fusion in patients younger than 5 years: How do thoracolumbar and lumbosacral curves compare? Spine Deform. 2019, 7, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, M. Operative Therapie der kongenitalen Skoliosen [Surgical treatment of congenital scoliosis]. Oper. Orthop. Traumatol. 2024, 36, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P.; Kowalski, P.; Rudziński, M.J.; Polis, B.; Grabala, M. The surgical management of severe scoliosis in immature patient with a very rare disease—Costello syndrome—Clinical example and brief literature review. Life 2024, 14, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P.; Danowska-Idziok, K.; Helenius, I.J. A rare complication of thoracic spine surgery: Pediatric Horner’s syndrome after posterior vertebral column resection—A case report. Children 2023, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, N.; Acosta Julbe, J.I.; Smith, J.; Emans, J.; Samdani, A.; Erickson, M.; Flynn, J.; Torres Lugo, N.J.; Claudio-Marcano, A.M.; Olivella, G.; et al. How does the vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib lengthening intervals affect the clinical outcome in early onset scoliosis patients? A five-year follow-up study. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redding, G.J.; Song, K.; Inscore, S.; Effmann, E.; Campbell, R.M. Lung function in children following thoracic insufficiency syndrome and vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib therapy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rizkallah, M.; Sebaaly, A.; Kharrat, K.; Kreichati, G. Is there still a place for convex hemiepiphysiodesis in congenital scoliosis in young children? A long-term follow-up. Glob. Spine J. 2020, 10, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motoyama, E.K.; Yang, C.I.; Deeney, V.F. Thoracic malformation with early-onset scoliosis: Effect of serial VEPTR expansion thoracoplasty on lung growth and function in children. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2009, 10, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkiran, G.; Yilmaz, G.; Kaymaz, B.; Akel, I.; Ayvaz, M.; Acaroglu, E.; Alanay, A.; Yazici, M. Safety and efficacy of instrumented convex growth arrest in treatment of congenital scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2014, 34, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marks, D.S.; Sayampanathan, S.R.; Thompson, A.G.; Piggott, H. Long-term results of convex epiphysiodesis for congenital scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 1995, 4, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walhout, R.J.; van Rhijn, L.W.; Pruijs, J.E.H. Hemi-epiphysiodesis for unclassified congenital scoliosis: Immediate results and mid-term follow-up. Eur. Spine J. 2002, 11, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; Herndon, W.A.; Levine, C.R. Surgical treatment of congenital scoliosis with or without Harrington instrumentation. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1981, 63, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.B.; Lonstein, J.E. Congenital scoliosis with posterior spinal arthrodesis T2–L3 at age 3 years with 41-year follow-up: A case report. Spine 1999, 24, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.B.; Moe, J.H.; Lonstein, J.E. Posterior spinal arthrodesis for congenital scoliosis: An analysis of the cases of two hundred and ninety patients, five to nineteen years old. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1984, 66, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.B.; Moe, J.H. The results of spinal arthrodesis for congenital spinal deformity in patients younger than five years old. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1982, 64, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Han, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. The progress of research on crankshaft phenomenon. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhu, C.; Luo, D.; Wang, Y.; Ai, Y.; Ding, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhou, C.; et al. Predictive value of the ratio of fusion segments to main curve segments for postoperative curve progression in congenital scoliosis with solitary hemivertebra. Eur. Spine J. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, C.; Du, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhuang, Q.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J. Incidence of the crankshaft phenomenon in thoracic congenital early-onset scoliosis patients followed until skeletal maturity. Neurosurgery 2025, 97, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesling, K.L.; Lonstein, J.E.; Denis, F.; Winter, R.B.; Sarwark, J.F.; Ogilvie, J.W. The crankshaft phenomenon after posterior spinal arthrodesis for congenital scoliosis: A review of 54 patients. Spine 2003, 28, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terek, R.M.; Wehner, J.; Lubicky, J.P. Crankshaft phenomenon in congenital scoliosis: A preliminary report. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1991, 11, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, X.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J. One-stage posterior excision of lumbosacral hemivertebrae: Retrospective study of case series and literature review. Medicine 2017, 96, e8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollini, G.; Docquier, P.L.; Launay, F.; Viehweger, E.; Jouve, J.L. Résultats à maturité osseuse après résection d’hémivertèbres par double abord. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Reparatrice Appar. Mot. 2005, 91, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, W.; Liu, F.; Xu, K.; Xia, B.; Zhao, Y. Posterior-only hemivertebra bone-disc-bone osteotomy (BDBO) without internal fixation in a 15-day-old neonate with 18-year follow-up. Eur. Spine J. 2025, 34, 4337–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holte, D.C.; Winter, R.B.; Lonstein, J.E.; Denis, F. Excision of hemivertebrae and wedge resection in the treatment of congenital scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1995, 77, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Qiu, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Di, D.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; et al. Adjacent intervertebral disc preservation or not during hemivertebra resection in the treatment of congenital scoliosis: A minimum of 5-year follow-up. Eur. Spine J. 2025, 34, 4295–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lin, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Lessons learned from short fusion with vertebrectomy for congenital early-onset scoliosis: A minimal follow-up of ten years until skeletal maturity. Bone Joint J. 2025, 107, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Sun, K.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Bao, H.; Shi, B.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Z. How to apply the sequential correction technique to treatment of congenital cervicothoracic scoliosis: A technical note and case series. Orthop. Surg. 2025, 17, 2159–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Long-term growth and risk factors for crankshaft phenomenon following posterior hemivertebra resection with mono-segment fusion in congenital early-onset scoliosis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, S.; Niu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K.; Tao, H.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y. Posterior hemivertebra extended resection combined with concave anterior column reconstruction for congenital scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, e538–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P.; Gupta, M.C.; Pereira, D.E.; Latalski, M.; Danielewicz, A.; Glowka, P.; Grabala, M. Radiological outcomes of magnetically controlled growing rods for the treatment of children with various etiologies of early-onset scoliosis: A multicenter study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odent, T.; Ilharreborde, B.; Miladi, L.; Khouri, N.; Violas, P.; Ouellet, J.; Cunin, V.; Kieffer, J.; Kharrat, K.; Accadbled, F.; et al. Fusionless surgery in early-onset scoliosis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2015, 101 (Suppl. 6), S281–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P. Minimally invasive controlled growing rods for the surgical treatment of early-onset scoliosis: A surgical technique video. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.M.; Cheung, J.P.; Samartzis, D.; Mak, K.C.; Wong, Y.W.; Cheung, W.Y.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Luk, K.D. Magnetically controlled growing rods for severe spinal curvature in young children: A prospective case series. Lancet 2012, 379, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannawi, Z.; Altaf, F.; Harshavardhana, N.S.; El Sebaie, H.; Noordeen, M.H. Early results of a remotely-operated magnetic growth rod in early-onset scoliosis. Bone Jt. J. 2013, 95, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlin, K.; Galgano, M.; Grabala, P. Magnetically controlled growing rods for early-onset scoliosis: 2-dimensional operative video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2023, 25, e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, B.A.; Towriss, C.; Baxter, G.; Yaszay, B.; Akbarnia, B.A. Early experience of MAGEC magnetic growing rods in the treatment of early onset scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.P.Y.; Bow, C.; Cheung, K.M.C. “Law of temporary diminishing distraction gains”: The phenomenon of temporary diminished distraction lengths with magnetically controlled growing rods that is reverted with rod exchange. Glob. Spine J. 2022, 12, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaferri, B.; Vommaro, F.; Cini, C.; Filardo, G.; Boriani, L.; Gasbarrini, A. Surgical Treatment of Early-Onset Scoliosis: Traditional Growing Rod vs. Magnetically Controlled Growing Rod vs. Vertical Expandable Prosthesis Titanium Ribs. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hawary, R.; Kadhim, M.; Vitale, M.; Smith, J.; Samdani, A.; Flynn, J.M.; Children’s Spine Study Group. VEPTR implantation to treat children with early-onset scoliosis without rib abnormalities: Early results from a prospective multicenter study. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2017, 37, e599–e605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.F.; Moisan, A.; Kelly, D.M.; Warner, W.C.; Jones, T.L.; Sawyer, J.R. Use of vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR) in the treatment of congenital scoliosis without fused ribs. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2016, 36, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P.; Helenius, I.J.; Chamberlin, K.; Galgano, M. Less-invasive approach to early-onset scoliosis: Surgical technique for magnetically controlled growing rod (MCGR) based on treatment of 2-year-old child with severe scoliosis. Children 2023, 10, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.H.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Kostial, P.; Poe-Kochert, C.; Armstrong, D.G.; Roh, J.; Lowe, R.; Asher, M.A.; Marks, D.S. Comparison of single and dual growing rod techniques followed through definitive surgery: A preliminary study. Spine 2005, 30, 2039–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bess, S.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Thompson, G.H.; Sponseller, P.D.; Shah, S.A.; El Sebaie, H.; Boachie-Adjei, O.; Karlin, L.I.; Canale, S.; Poe-Kochert, C.; et al. Complications of growing-rod treatment for early-onset scoliosis: Analysis of one hundred and forty patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2010, 92, 2533–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnell, S.E.; Effmann, E.L.; Song, K.; Swanson, J.O.; Bompadre, V.; Phillips, G.S. Vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR): A review of indications, normal radiographic appearance and complications. Pediatr. Radiol. 2015, 45, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samdani, A.F.; Ranade, A.; Dolch, H.J.; Williams, R.; St Hilaire, T.; Cahill, P.; Betz, R.R. Bilateral use of the vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib attached to the pelvis: A novel treatment for scoliosis in the growing spine. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2009, 10, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, R.; Shah, P.; Jones, A.; Ahuja, S.; Howes, J. Operative management of congenital early-onset scoliosis using the vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR): A case series. World J. Pediatr. Surg. 2025, 8, e000972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElNemer, W.; Cha, M.J.; Benes, G.; Andras, L.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Bumpass, D.; Luhmann, S.; McCarthy, R.; Sponseller, P.D.; Pediatric Spine Study Group. Shilla Growth Guidance Surgery for Early Onset Scoliosis: Predictors of Optimal Versus Suboptimal Performers. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, A.; Skaggs, D.L.; Illingworth, K.D.; Parent, S.; Shah, S.A.; Sanders, J.O.; Andras, L.M.; Growing Spine Study Group. Growth guidance constructs with apical fusion and sliding pedicle screws (SHILLA) results in approximately 1/3rd of normal T1–S1 growth. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andras, L.M.; Joiner, E.R.; McCarthy, R.E.; McCullough, L.; Luhmann, S.J.; Sponseller, P.D.; Emans, J.B.; Barrett, K.K.; Skaggs, D.L.; Growing Spine Study Group. Growing Rods Versus Shilla Growth Guidance: Better Cobb Angle Correction and T1-S1 Length Increase But More Surgeries. Spine Deform. 2015, 3, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miękisiak, G.; Kołtowski, K.; Menartowicz, P.; Oleksik, Z.; Kotulski, D.; Potaczek, T.; Repko, M.; Filipovič, M.; Danielewicz, A.; Fatyga, M.; et al. The titanium-made growth-guidance technique for early-onset scoliosis at minimum 2-year follow-up: A prospective multicenter study. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 28, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauchi, R.; Tsuji, T.; Ohara, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Saito, T.; Nohara, A.; Sugawara, R.; Imagama, S.; Kawakami, N. Reconstructive surgery for the post-hemiepiphysiodesis residual deformity in congenital scoliosis. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2013, 23 (Suppl. 1), S111–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, S.I.; Chung, E.R.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, W.K. Posterior vertebral column resection for severe rigid scoliosis. Spine 2005, 30, 1682–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, S.I.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, S.M.; Chung, E.R.; Nah, K.H. Posterior vertebral column resection for severe spinal deformities. Spine 2002, 27, 2374–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabala, P.; Fani, N.; Gregorczyk, J.; Grabala, M. Posterior-only T11 vertebral column resection for pediatric congenital kyphosis surgical correction. Medicina 2024, 60, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.C. Vertebral column resection for severe kyphosis. Neurosurg. Focus. Video 2020, 2, V10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenke, L.G.; Newton, P.O.; Sucato, D.J.; Shufflebarger, H.L.; Emans, J.B.; Sponseller, P.D.; Shah, S.A.; Sides, B.A.; Blanke, K.M. Complications after 147 consecutive vertebral column resections for severe pediatric spinal deformity: A multicenter analysis. Spine 2013, 38, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asunis, E.; Cini, C.; Martikos, K.; Vommaro, F.; Evangelisti, G.; Griffoni, C.; Gasbarrini, A. Efficacy and Risks of Posterior Vertebral Column Resection in the Treatment of Severe Pediatric Spinal Deformities: A Case Series. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Li, T.; Bi, N.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y. Posterior Vertebral Column Resection for Severe Spinal Deformity Correction: Comparison of Pediatric, Adolescent, and Adult Groups. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5730856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.; Zandi, R.; Hassani, M.; Elsebaie, H.B. Thoracolumbar and Lumbar Posterior Vertebral Resection for the Treatment of Rigid Congenital Spinal Deformities in Pediatric Patients: A Long-Term Follow-up Study. World Neurosurg. X 2022, 16, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boachie-Adjei, O.; Duah, H.O.; Yankey, K.P.; Lenke, L.G.; Sponseller, P.D.; Sucato, D.J.; Samdani, A.F.; Newton, P.O.; Shah, S.A.; Erickson, M.A.; et al. New neurologic deficit and recovery rates in the treatment of complex pediatric spine deformities exceeding 100 degrees or treated by vertebral column resection (VCR). Spine Deform. 2021, 9, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.; Andras, L.M.; Nielsen, E.; Sousa, T.; Joiner, E.; Choi, P.D.; Tolo, V.T.; Skaggs, D.L. Comparison of Ponte Osteotomies and 3-Column Osteotomies in the Treatment of Congenital Spinal Deformity. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento-Domínguez, C.; Cynthia, N.; Yankey, K.P.; Tutu, H.O.; Wulff, I.; Akoto, H.; Boachie-Adjei, O.; Focos Spine Research Group. One-stage multiple posterior column osteotomies and fusion and pre-op halo-gravity traction may result in a comparative and safer correction of complex spine deformity than vertebral column resection. Spine Deform. 2021, 9, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, M.; Emans, J. Dual growing rod instrumentation in children with spinal deformity: When do the rods break and what happens next? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2010, 30, 294–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Baldus, C.; Blanke, K. Major intraoperative neurologic deficits in pediatric and adult spinal deformity patients: Incidence and etiology at one institution. Spine 1999, 24, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekmez, S.; Dede, O.; Yazici, M.; Alanay, A.; Acaroglu, E. Hemivertebra resection from posterior approach only: A systematic review. Spine Deform. 2017, 5, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rybaczek, M.; Kowalski, P.; Mariak, Z.; Grabala, M.; Suszczyńska, J.; Łysoń, T.; Grabala, P. Safety in Spine Surgery: Risk Factors for Intraoperative Blood Loss and Management Strategies. Life 2025, 15, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabala, P.; Helenius, I.J.; Buchowski, J.M.; Shah, S.A. The efficacy of a posterior approach to surgical correction for neglected idiopathic scoliosis: A comparative analysis according to health-related quality of life, pulmonary function, back pain and sexual function. Children 2023, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, R.R.; D’Andrea, L.P.; Mulcahey, M.J.; Chafetz, R.S. The health and activity profile and spinal appearance questionnaire in the assessment of patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000, 374, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Whelan, T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukavarapu, S.P.; Dorcemus, D.L. Osteochondral tissue engineering: Current strategies and challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarnia, B.A.; Marks, D.S.; Boachie-Adjei, O.; Thompson, G.H.; Asher, M.A. Dual growing rod technique for the treatment of progressive early-onset scoliosis: A multicenter study. Spine 2005, 30, S46–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Risk Factor | Details |

|---|---|

| Type of anomaly | - Multiple anomalies and mixed malformations increase progression risk [66] - Worst prognosis: unilateral bar with contralateral hemivertebra [3,6,30] - Most benign: complete block vertebra/incarcerated hemivertebra [3,6,30] - Fully segmented hemivertebra with healthy disc spaces predicts faster progression [3,6] - Presence of more than one hemivertebra increases progression rate [35,56,71] - Hemimetameric shifts, especially in thoracolumbar region, may lead to progression [56,67,72] - Bone bar or fused ribs may act as tethers and promote curve progression [35,42,56] |

| Apex location | - Upper thoracic curves: slowest progression - Mid-thoracic: faster progression - Thoracolumbar region: greatest progression, possibly due to thoracic cage influence and pressure divergence [43] |

| Patient’s age | - Greatest progression before age 5 and during adolescent growth spurt (ages 11–14) [35] - Curves visible before age 10 = poorer prognosis due to higher growth potential [30,61] - Deformities obvious in early infancy = worst prognosis [3,6,42] |

| Curve characteristics | - Two unilateral curves cause significant malformation. - Contralateral curves may help balance the spine [56,61] - Cobb angle ≤ 25° → unlikely progression [13] - Progression of a unilateral unsegmented bar also depends on its extent [23,43,56] |

| Growth asymmetry | - Progression linked to asymmetric growth between convex and concave sides, with most growth on the convex side [71] |

| Additional notes | - Progression occurs on “normal” disc spaces; fused segments do not progress [3,26] - Progression velocity depends on age, apex location, anomaly type, and curve characteristics [3,26] |

| Additional progression stats |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grabala, P. Congenital Scoliosis: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Surgical Decision-Making in Pediatric Spinal Deformity—An Expanded Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228085

Grabala P. Congenital Scoliosis: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Surgical Decision-Making in Pediatric Spinal Deformity—An Expanded Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228085

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrabala, Paweł. 2025. "Congenital Scoliosis: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Surgical Decision-Making in Pediatric Spinal Deformity—An Expanded Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228085

APA StyleGrabala, P. (2025). Congenital Scoliosis: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Surgical Decision-Making in Pediatric Spinal Deformity—An Expanded Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228085