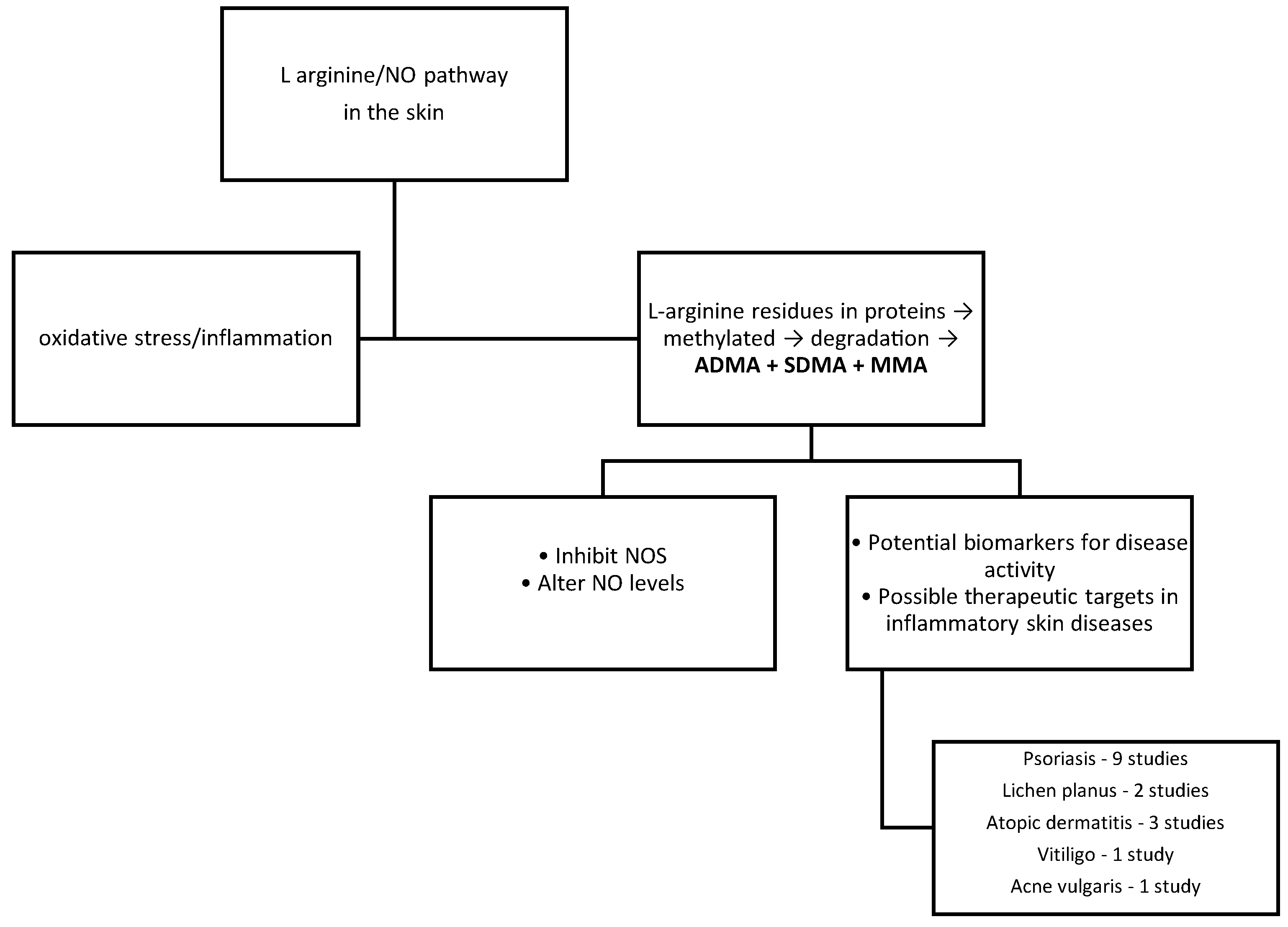

Methylarginine Levels in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases—The Role of L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Methylarginines in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases

3.1. Psoriasis

| Disease | Study Participants | Study Type | PASI | Parameter (Patients Versus Controls) | Sample | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | 59 patients 40 controls | Case–control. | Not available | ADMA—higher (1.15 ± 0.43 vs. 0.76 ± 0.39 µmol/L) | Serum | ADMA plays an important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, and the development of therapies aimed at lowering its levels could open new perspectives in psoriasis treatment. | Göçer Gürok et al. (2025) [34] |

| Psoriasis Atopic dermatitis | 20 psoriasis patients 15 atopic dermatitis patients | Case–control | 7.7 ± 2.3 | ADMA—higher in psoriasis patients (0.4483 vs. 0.1622 µmol/L) | Skin | These differences suggest the different pathogenic mechanisms underlying the occurrence of the 2 diseases | Ilves et al. (2021) [46] |

| Psoriasis | 20 patients 19 controls | Case–control | Not available | ADMA—higher (lesional skin vs. non-lesional skin) (1.419 vs. 0.475 µmol/L) ADMA—higher (lesional skin vs. control) (1.419 vs. 0.571 µmol/L) | Lesional skin Healthy skin (from psoriasis patients) Control skin (from controls) | The accumulation of ADMA in the skin of patients with psoriasis indicates its role in disease pathogenesis | Pohla et al. (2020) [47] |

| Psoriasis | 29 patients with psoriasis before treatment with adalimumab 29 patients with psoriasis after treatment with adalimumab | Prospective cohort study | 18.9 ± 7.8 | ADMA -correlated with BSA (1.523 vs. 0.403 µmol/L + before and after treatment with adalimumab) | Serum | ADMA may be a marker of disease severity in patients with psoriasis and a predictor of the response to treatment | Pina et al. (2016) [33] |

| Psoriasis | 40 patients 40 controls | Case–control | Not available | ADMA—higher (1.49 ± 0.09 vs. 0.46 ± 0.06 µmol/L) | Serum | ADMA can be considered a marker of disease severity, given that in patients with severe forms the levels were higher than in those with mild forms. | Abdul Kareem et al. (2016) [48] |

| Psoriasis | 40 patients 40 controls | Case–control | 5.32 ± 4.09 | ADMA—NS (0.19 ± 0.06 vs. 0.17 ± 0.084 µmol/L) | Serum | The role of ADMA is unclear in the pathogenesis of psoriasis; further studies are needed. | Bilgiç et al. (2016) [49] |

| Psoriasis | 42 patients 48 controls | Case–control | 10.64 ± 6.77 | ADMA—higher (1.08 ± 0.23 vs. 0.60 ± 0.25 µmol/L) SDMA—NS (1.07 ± 0.29 vs. 0.94 ± 0.47 µmol/L) L-NMMA—NS (0.13 ± 0.14 vs. 0.66 ± 0.79 µmol/L) | Serum | Among L-arginine/NO pathway metabolites, ADMA appears to hold the most important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. | Bilgiç et al. (2015) [31] |

| Psoriasis | 35 patients 26 controls | Case–control | 4.6 ± 5.7 | ADMA-NS (0.63 ± 0.30 vs. 0.68 ± 0.65 µmol/L) | Serum | ADMA does not represent an indicator of endothelial disfunction in psoriasis patients | Turan et al. (2014) [50] |

| Psoriasis | 29 patients 25 controls | Case–control | 4.6 ± 3.8 | ADMA—NS (0.44 ± 0.06 vs. 0.46 ± 0.07 µmol/L) | Serum | In patients with mild/moderate forms of psoriasis associated with mild inflammation, serum ADMA levels do not increase. | Usta et al. (2011) [32] |

3.2. Vitiligo

3.3. Atopic Dermatitis

3.4. Lichen Planus

3.5. Acne Vulgaris

| Disease | Study Participants | Study Type | Clinical Characteristics | Parameter (Patients Versus Controls) | Sample | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lichen planus | 40 patients 40 controls | Case–control | Classic lichen planus—31 patients Hypertrophic lichen planus—6 patients Annular lichen planus—3 patients Oral lichen planus—patients | SDMA—higher (0.82 ± 0.20 vs. 0.49 ± 0.06 µmol/L) | Serum | Nitrosation stress may play a role in the pathogenesis of cutaneous lichen planus. | Tampa et al. (2024) [60] |

| Atopic diseases (bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis) | 81 patients 30 controls (individuals without allergy) | Case–control | Moderate atopic dermatitis—36 patients Severe atopic dermatitis—9 patients | ADMA—NS (plasma) (0.68 vs. 0.65 µmol/L) ADMA—NS (urine) (6.17 vs. 7.24 µmol/L) SDMA—NS (urine) (6.71 vs. 6.59 µmol/L) | Plasma, urine | L-arginine/NO pathway abnormalities in patients with atopic diseases do not correlate with disease severity | Hanusch et al. (2022) [57] |

| Atopic dermatitis | 17 patients | Case–control | Not available | ADMA—higher (lesional skin vs. non-lesional skin) (0.519 vs. 0.262 µmol/L) | Lesional skin Healthy skin (from atopic dermatitis patients) | ADMA could serve as a biomarker of inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in atopic dermatitis. | Ilves et al. (2022) [43] |

| Lichen planus | 31 patients 26 controls | Case–control | Cutaneous lichen planus—31 patients Oral lichen planus—5 patients Lichen planopilaris—1 patient Nail lichen planus—3 patients | SDMA—higher (0.84 ± 0.19 vs. 0.50 ± 0.06 µmol/L) | Serum | SDMA may represent a potential marker of oxidative stress in patients with lichen planus. | Mitran et al. (2021) [65] |

| Acne vulgaris | 90 patients 30 controls | Case–control | Mild acne—30 patients Moderate acne—30 patients Severe acne—30 patients | ADMA—higher (0.48 ± 0.15 vs. 0.37 ± 0.12 µmol/L) SDMA—higher (0.48 ± 0.19 vs. 0.41 ± 0.12 µmol/L) L-NMMA—higher (0.07 ± 0.03 vs. 0.06 ± 0.02 µmol/L) | Plasma | L-arginine/NO pathway is involved in the pathogenic processes observed in acne and influences the course of the disease | Tunçez Akyürek et al. (2020) [63] |

| Vitiligo | 30 patients 20 controls | Case–control | Not available | ADMA—higher (0.49 ± 0.2 vs. 0.32.0.1 µmol/L) | Serum | Increased levels of ADMA may be involved in the pathogenesis of vitiligo | Kaman et al. (2016) [53] |

4. Methylarginines in Other Skin Diseases

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caldwell, R.W.; Rodriguez, P.C.; Toque, H.A.; Narayanan, S.P.; Caldwell, R.B. Arginase: A Multifaceted Enzyme Important in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 641–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, A.; Farahani, A.; Kashfi, K.; Ghasemi, A. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS): More than an Inducible Enzyme? Rethinking the Classification of NOS Isoforms. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 216, 107781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.; Rivas, J.C.; González, M.; Rivas, J.C. L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway and KCa Channels in Endothelial Cells: A Mini-Review. In Vascular Biology—Selection of Mechanisms and Clinical Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, M.S. Nitric Oxide Signal Transduction and Its Role in Skin Sensitization. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liy, P.M.; Puzi, N.N.A.; Jose, S.; Vidyadaran, S. Nitric Oxide Modulation in Neuroinflammation and the Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, S.M.; Sharma, N.S.; Karan, A.; Shahriar, S.M.S.; Cordon, B.; Ma, B.; Xie, J. Nitric Oxide: Physiological Functions, Delivery, and Biomedical Applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T.; Fernandez-Lopez, E.; Silk, A.W.; Dummer, R.; Bhatia, S. Immunologic Characteristics of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers: Implications for Immunotherapy. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2020, 40, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Nitric Oxide Signaling in Health and Disease. Cell 2022, 185, 2853–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborova, V.; Budanova, E.; Kryuchkova, K.; Rybakov, V.; Shestakov, D.; Isaikin, A.; Romanov, D.; Churyukanov, M.; Vakhnina, N.; Zakharov, V.; et al. Nitric Oxide: A Gas Transmitter in Healthy and Diseased Skin. Med. Gas Res. 2025, 15, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, C.; Tampa, M.; Caruntu, C.; Ion, R.-M.; Georgescu, S.-R.; Dumitrascu, G.R.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M. Protein Microarray for Complex Apoptosis Monitoring of Dysplastic Oral Keratinocytes in Experimental Photodynamic Therapy. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayatri, S.; Bedford, M.T. Readers of Histone Methylarginine Marks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gene Regul. Mech. 2014, 1839, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, N.; Khan, S.; Richard, S. The Influence of Arginine Methylation in Immunity and Inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 2939–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-κB in Biology and Targeted Therapy: New Insights and Translational Implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancic, A.; Jankovic, A.; Korac, A.; Buzadzic, B.; Otasevic, V.; Korac, B. The Role of Nitric Oxide in Diabetic Skin (Patho)Physiology. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2018, 172, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Taylor, M.; Cook, C.; Martínez-Berdeja, A.; North, J.P.; Harirchian, P.; Hailer, A.A.; Zhao, Z.; Ghadially, R.; et al. Classification of Human Chronic Inflammatory Skin Disease Based on Single-Cell Immune Profiling. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabl9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Personalized Medicine—Concepts, Technologies, and Applications in Inflammatory Skin Diseases. APMIS 2019, 127, 386–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.W.; Kupper, T.S. T Cells and the Skin: From Protective Immunity to Inflammatory Skin Disorders. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erre, G.L.; Mangoni, A.A.; Castagna, F.; Paliogiannis, P.; Carru, C.; Passiu, G.; Zinellu, A. Meta-Analysis of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Concentrations in Rheumatic Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzebska, N.; Mangoni, A.A.; Martens-Lobenhoffer, J.; Bode-Böger, S.M.; Rodionov, R.N. The Second Life of Methylarginines as Cardiovascular Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.; Hsu, C. Toxic Dimethylarginines: Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) and Symmetric Dimethylarginine (SDMA). Toxins 2017, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaut, C.; Eve, L.; Poulard, C.; Le Romancer, M. Structure, Activity, and Function of PRMT1. Life 2021, 11, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolae, I.; Tampa, M.; Grigore, M.; Mitran, C.I.; Mitran, M.I.; Dulgheru, L.; Georgescu, S.R. Symmetrical Dimethylarginine (Sdma)And Venous Ulcer Of THE Lower Limbs. Dermatovenerol. J. 2020, 65, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schwedhelm, E.; Böger, R.H. The Role of Asymmetric and Symmetric Dimethylarginines in Renal Disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2011, 7, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, P.; Leiper, J. Cardiovascular Biology of the Asymmetric Dimethylarginine: Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase Pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, R.N.; Jarzebska, N.; Burdin, D.; Todorov, V.; Martens-Lobenhoffer, J.; Hofmann, A.; Kolouschek, A.; Cordasic, N.; Jacobi, J.; Rubets, E.; et al. Overexpression of Alanine-Glyoxylate Aminotransferase 2 Protects from Asymmetric Dimethylarginine-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction and Aortic Remodeling. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cziráki, A.; Lenkey, Z.; Sulyok, E.; Szokodi, I.; Koller, A. L-Arginine-Nitric Oxide-Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Pathway and the Coronary Circulation: Translation of Basic Science Results to Clinical Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 569914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzystek-Korpacka, M.; Szczęśniak-Sięga, B.; Szczuka, I.; Fortuna, P.; Zawadzki, M.; Kubiak, A.; Mierzchała-Pasierb, M.; Fleszar, M.G.; Lewandowski, Ł.; Serek, P.; et al. L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway Is Altered in Colorectal Cancer and Can Be Modulated by Novel Derivatives from Oxicam Class of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Cancers 2020, 12, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Koca, C.; Uysal, S.; Totan, Y.; Yağci, R.; Armutcu, F.; Cücen, Z.; YiĞiToğlu, M.R. Serum Nitric Oxide, Asymmetric Dimethylarginine, and Plasma Homocysteine Levels in Active Behçet’s Disease. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 42, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, M.-Q.; Wakefield, J.S.; Mauro, T.M.; Elias, P.M. Regulatory Role of Nitric Oxide in Cutaneous Inflammation. Inflammation 2022, 45, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settelmeier, S.; Rassaf, T.; Hendgen-Cotta, U.B.; Stoffels, I. Nitric Oxide Generating Formulation as an Innovative Approach to Topical Skin Care: An Open-Label Pilot Study. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgiç, Ö.; Altınyazar, H.C.; Baran, H.; Ünlü, A. Serum Homocysteine, Asymmetric Dimethyl Arginine (ADMA) and Other Arginine–NO Pathway Metabolite Levels in Patients with Psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2015, 307, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, M.; Yurdakul, S.; Aral, H.; Turan, E.; Oner, E.; Inal, B.B.; Oner, F.A.; Gurel, M.S.; Guvenen, G. Vascular Endothelial Function Assessed by a Noninvasive Ultrasound Method and Serum Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Concentrations in Mild-to-Moderate Plaque-Type Psoriatic Patients. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 44, 1080–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, T.; Genre, F.; Lopez-Mejias, R.; Armesto, S.; Ubilla, B.; Mijares, V.; Dierssen-Sotos, T.; Corrales, A.; Gonzalez-Lopez, M.A.; Gonzalez-Vela, M.C.; et al. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine but Not Osteoprotegerin Correlates with Disease Severity in Patients with Moderate-to-severe Psoriasis Undergoing Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor-α Therapy. J. Dermatol. 2016, 43, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göçer Gürok, N.; Telo, S.; Genç Ulucan, B.; Öztürk, S. Oxidative Stress in Psoriasis Vulgaris Patients: Analysis of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine, Malondialdehyde, and Glutathione Levels. Medicina 2025, 61, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medovic, M.V.; Jakovljevic, V.L.; Zivkovic, V.I.; Jeremic, N.S.; Jeremic, J.N.; Bolevich, S.B.; Ravic Nikolic, A.B.; Milicic, V.M.; Srejovic, I.M. Psoriasis between Autoimmunity and Oxidative Stress: Changes Induced by Different Therapeutic Approaches. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2249834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoei, S.; Nakhjavani, M.; Mirmiranpoor, H.; Motlagh, M.A.; Azizpour, A.; Abedini, R. The Serum Level of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Markers in Patients with Psoriasis: A Cross-sectional Study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021, 14, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blagov, A.; Sukhorukov, V.; Guo, S.; Zhang, D.; Eremin, I.; Orekhov, A. The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Induction and Development of Psoriasis. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2023, 28, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, V.; Pascale, W.; Lavanga, V.; Sansone, V.; Ferrario, P.; De Gennaro Colonna, V. L-Arginine, Asymmetric Dimethylarginine, and Symmetric Dimethylarginine in Plasma and Synovial Fluid of Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2013, 19, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, G.; Molon, B.; Viola, A.; Alaibac, M.; Angioni, R.; Piaserico, S. Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Diseases: An Immune-Mediated Cross Talk? Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 868277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yin, S.; Qin, Z.; Yu, H. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Psoriasis: From Clinical Practice to Basic Research. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapone, B.; Inchingolo, F.; Tartaglia, G.M.; De Francesco, M.; Ferrara, E. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine as a Potential Mediator in the Association between Periodontitis and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, S.K.; Verma, J.; Sonkar, G.K.; Gupta, A.; Singh, A.; Vishwakarma, P.; Bhosale, V. Assessing the Role of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine in Endothelial Dysfunction: Insights Into Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Cureus 2025, 17, e77565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilves, L.; Ottas, A.; Kaldvee, B.; Abram, K.; Soomets, U.; Zilmer, M.; Jaks, V.; Kingo, K. Metabolomic Differences between the Skin and Blood Sera of Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Sitia, S.; Tomasoni, L.; Gianturco, L.; Battellino, M.; Boccassini, L.; De Gennaro Colonna, V.; Marchesoni, A.; Turiel, M. Coronary Flow Reserve and Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Levels: New Measurements for Identifying Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 38, 1661–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.Z.; Plazyo, O.; Gudjonsson, J.E. Targeting Immune Cell Trafficking and Vascular Endothelial Cells in Psoriasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e169450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilves, L.; Ottas, A.; Kaldvee, B.; Abram, K.; Soomets, U.; Zilmer, M.; Jaks, V.; Kingo, K. Metabolomic Analysis of Skin Biopsies from Patients with Atopic Dermatitis Reveals Hallmarks of Inflammation, Disrupted Barrier Function and Oxidative Stress. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohla, L.; Ottas, A.; Kaldvee, B.; Abram, K.; Soomets, U.; Zilmer, M.; Reemann, P.; Jaks, V.; Kingo, K. Hyperproliferation Is the Main Driver of Metabolomic Changes in Psoriasis Lesional Skin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Kareem, I.A.; Hamzah, M.I.; Farhood, I.G.; Hasan, M.M. Study of Asymmetric Dimethyl Arginine (ADMA) and Anti Cyclic Citrulinated Peptide (Anti-CCP) in Iraqi Patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgiç, R.; Yıldız, H.; Karabudak Abuaf, Ö.; İpçioğlu, O.M.; Doğan, B. Evaluation of serum asymmetric dimethylarginine levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Turkderm 2016, 49 (Suppl. S1), 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, H.; Arslanyılmaz, Z.; Bulur, S.; Acer, E.; Uslu, E.; Albayrak, H.; Aslantaş, Y.; Memişoğulları, R. Psoriazisli Hastalarda Serum Asimetrik Dimetilarjinin (ADMA) ve Yüksek Sensitif C-Reaktif Protein (Hscrp) Seviyeleri. Düzce Tıp Fakültesi Derg. 2014, 16, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Diotallevi, F.; Gioacchini, H.; De Simoni, E.; Marani, A.; Candelora, M.; Paolinelli, M.; Molinelli, E.; Offidani, A.; Simonetti, O. Vitiligo, from Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Advances: State of the Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speeckaert, R.; Caelenberg, E.V.; Belpaire, A.; Speeckaert, M.M.; Geel, N.V. Vitiligo: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaman, D.; DemiR, B. Vitiligolu Hastalarda Serum ADMA, MDA, Vitamin E ve Homosistein Düzeyleri. Fırat Tıp Derg./Firat Med. J. 2016, 21, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, C.F.; Tsoi, L.C.; Billi, A.C.; Harms, P.W.; Weidinger, S.; Gudjonsson, J.E. Genetic and Immunological Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Kolackova, M.; Rosecka, M.; Čelakovská, J.; Krejsek, J. Unraveling the Skin; a Comprehensive Review of Atopic Dermatitis, Current Understanding, and Approaches. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1361005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, M.; Steinhoff, A.; Homey, B.; Luger, T.A.; Schneider, S.W. Role of Vasculature in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanusch, B.; Sinningen, K.; Brinkmann, F.; Dillenhöfer, S.; Frank, M.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Koerner-Rettberg, C.; Holtmann, M.; Legenbauer, T.; Langrock, C.; et al. Characterization of the L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway and Oxidative Stress in Pediatric Patients with Atopic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, S.; Tampa, M.; Mitran, M.; Mitran, C.; Sarbu, M.; Nicolae, I.; Matei, C.; Caruntu, C.; Neagu, M.; Popa, M. Potential Pathogenic Mechanisms Involved in the Association between Lichen Planus and Hepatitis C Virus Infection (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 17, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vičić, M.; Hlača, N.; Kaštelan, M.; Brajac, I.; Sotošek, V.; Prpić Massari, L. Comprehensive Insight into Lichen Planus Immunopathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampa, M.; Nicolae, I.; Ene, C.D.; Mitran, C.I.; Mitran, M.I.; Matei, C.; Georgescu, S.R. The Interplay between Nitrosative Stress, Inflammation, and Antioxidant Defense in Patients with Lichen Planus. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, N. Acne Vulgaris: New Evidence in Pathogenesis and Future Modalities of Treatment. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Navarro-Moratalla, L.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Ruzafa-Costas, B.; Agüera-Santos, J.; Navarro-López, V. Acne, Microbiome, and Probiotics: The Gut–Skin Axis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçez Akyürek, F.; Saylam Kurtipek, G.; Kurku, H.; Akyurek, F.; Unlu, A.; Abusoglu, S.; Ataseven, A. Assessment of ADMA, IMA, and Vitamin A and E Levels in Patients with Acne Vulgaris. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 3408–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumtornrut, C.; Manabe, S.D.; Navapongsiri, M.; Okutani, Y.; Ikegaki, S.; Tanaka, N.; Hashimoto, H.; Songsantiphap, C.; Wantavornprasert, K.; Khamthara, J.; et al. A Cleanser Formulated with Tris (Hydroxymethyl) Aminomethane and L-arginine Significantly Improves Facial Acne in Male Thai Subjects. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitran, M.I.; Tampa, M.; Nicolae, I.; Mitran, C.I.; Matei, C.; Georgescu, S.R.; Popa, M.I. New Markers of Oxidative Stress in Lichen Planus and the Influence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection—A Pilot Study. Rom. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 59, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosman, L.M.; Țăpoi, D.-A.; Costache, M. Cutaneous Melanoma: A Review of Multifactorial Pathogenesis, Immunohistochemistry, and Emerging Biomarkers for Early Detection and Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruntu, C.; Mirica, A.; Roşca, A.E.; Mirica, R.; Caruntu, A.; Tampa, M.; Matei, C.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M.; Badarau, A.I.; et al. The Role of Estrogens and Estrogen Receptors in Melanoma Development and Progression. Acta Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, C.D.; Nicolae, I. Hypoxia-Nitric Oxide Axis and the Associated Damage Molecular Pattern in Cutaneous Melanoma. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Lowery, A.T.; Lin, S.; Walker, A.M.; Chen, K.-H.E. Tumor Cell-Derived Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Regulates Macrophage Functions and Polarization. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Tampa, M.; Matei, C.; Lupu, A.; Manole, E.; Ion, R.-M.; Fenga, C.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Toxicological and Efficacy Assessment of Post-Transition Metal (Indium) Phthalocyanine for Photodynamic Therapy in Neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 69718–69732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunnetcioglu, M.; Mengeloglu, Z.; Baran, A.I.; Karahocagil, M.; Tosun, M.; Kucukbayrak, A.; Ceylan, M.R.; Akdeniz, H.; Aypak, C. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Levels in Patients with Cutaneous Anthrax: A Laboratory Analysis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2014, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, S.K.; Kaldirim, Ü.; Eyi, Y.E.; Yildirim, A.O.; Ekici, Ş.; Kara, K.; Eroğlu, M.; Öztosun, M.; Özyürek, S.; Durusu, M.; et al. Neopterin, Homocysteine, and ADMA Levels during and after Urticaria Attack. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 45, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canè, S.; Geiger, R.; Bronte, V. The Roles of Arginases and Arginine in Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, M.; Zhang, K.; Han, S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. mTOR Inhibition Restores Amino Acid Balance in Cells Dependent on Catabolism of Extracellular Protein. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 936–946.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Diedrich, J.K.; Wu, D.C.; Lim, J.J.; Nottingham, R.M.; Moresco, J.J.; Yates, J.R.; Blencowe, B.J.; Lambowitz, A.M.; Schimmel, P. Arg-tRNA Synthetase Links Inflammatory Metabolism to RNA Splicing and Nuclear Trafficking via SRRM2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ibrahimi, O.A.; Olsen, S.K.; Umemori, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Ornitz, D.M. Receptor Specificity of the Fibroblast Growth Factor Family. The Complete Mammalian FGF Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 15694–15700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.J.; Gao, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Pinzaru, A.; Wu, Q.; Mandayam, N.; Liberti, M.; Heissel, S.; Alwaseem, H.; Tavazoie, S.; et al. Arginine Limitation Drives a Directed Codon-Dependent DNA Sequence Evolution Response in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.M.; Maghe, C.; Tapia, K.; Wu, S.; Yang, S.; Ren, X.; Zoncu, R.; Hurley, J.H. Structural Basis for mTORC1 Regulation by the CASTOR1–GATOR2 Complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2025, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.G.; Pearce, E.J. MenTORing Immunity: mTOR Signaling in the Development and Function of Tissue-Resident Immune Cells. Immunity 2017, 46, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibrian, D.; de la Fuente, H.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Metabolic Pathways That Control Skin Homeostasis and Inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarandi, E.; Krueger-Krasagakis, S.; Tsoukalas, D.; Sidiropoulou, P.; Evangelou, G.; Sifaki, M.; Rudofsky, G.; Drakoulis, N.; Tsatsakis, A. Psoriasis Immunometabolism: Progress on Metabolic Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1201912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Shang, G. The Role of Protein Arginine N-Methyltransferases in Inflammation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 154, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matei, C.; Tampa, M.; Mitran, M.I.; Mitran, C.I.; Nicolae, I.; Ene, C.D.; Marin, A.; Rinja, E.; Dumitru, A.; Caruntu, C.; et al. Methylarginine Levels in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases—The Role of L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7934. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227934

Matei C, Tampa M, Mitran MI, Mitran CI, Nicolae I, Ene CD, Marin A, Rinja E, Dumitru A, Caruntu C, et al. Methylarginine Levels in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases—The Role of L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7934. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227934

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatei, Clara, Mircea Tampa, Madalina Irina Mitran, Cristina Iulia Mitran, Ilinca Nicolae, Corina Daniela Ene, Andrei Marin, Ecaterina Rinja, Adrian Dumitru, Constantin Caruntu, and et al. 2025. "Methylarginine Levels in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases—The Role of L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7934. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227934

APA StyleMatei, C., Tampa, M., Mitran, M. I., Mitran, C. I., Nicolae, I., Ene, C. D., Marin, A., Rinja, E., Dumitru, A., Caruntu, C., Constantin, C., Neagu, M., & Georgescu, S. R. (2025). Methylarginine Levels in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases—The Role of L-Arginine/Nitric Oxide Pathway. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7934. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227934