Motor Imagery for Post-Stroke Upper Limb Recovery: A Meta-Analysis of RCTs on Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Scores

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- (1)

- adult participants with a clinical diagnosis of stroke presenting upper-limb motor impairment, regardless of stroke type, severity, or recovery phase;

- (2)

- interventions combining MI or MP with CRT;

- (3)

- control groups receiving the same CRT protocol as the intervention group, without MI;

- (4)

- upper-limb motor outcomes assessed through the FM-UE scale; and

- (5)

- RCTs, including pilot or crossover RCTs.

- (1)

- studies combining MI with other non-conventional interventions (e.g., virtual reality, mirror therapy, or brain–computer interfaces);

- (2)

- studies not reporting sufficient data for effect size calculation; and

- (3)

- non-randomized, quasi-experimental, or single-case designs.

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias and the Assessment of Methodological Quality of the Studies

2.7. Overall Quality of Evidence

2.8. Studies Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.8.1. Heterogeneity in ES Estimates

2.8.2. Sensitivity Analysis

2.8.3. Publication Bias Analysis

2.8.4. Moderator Analyses

3. Results

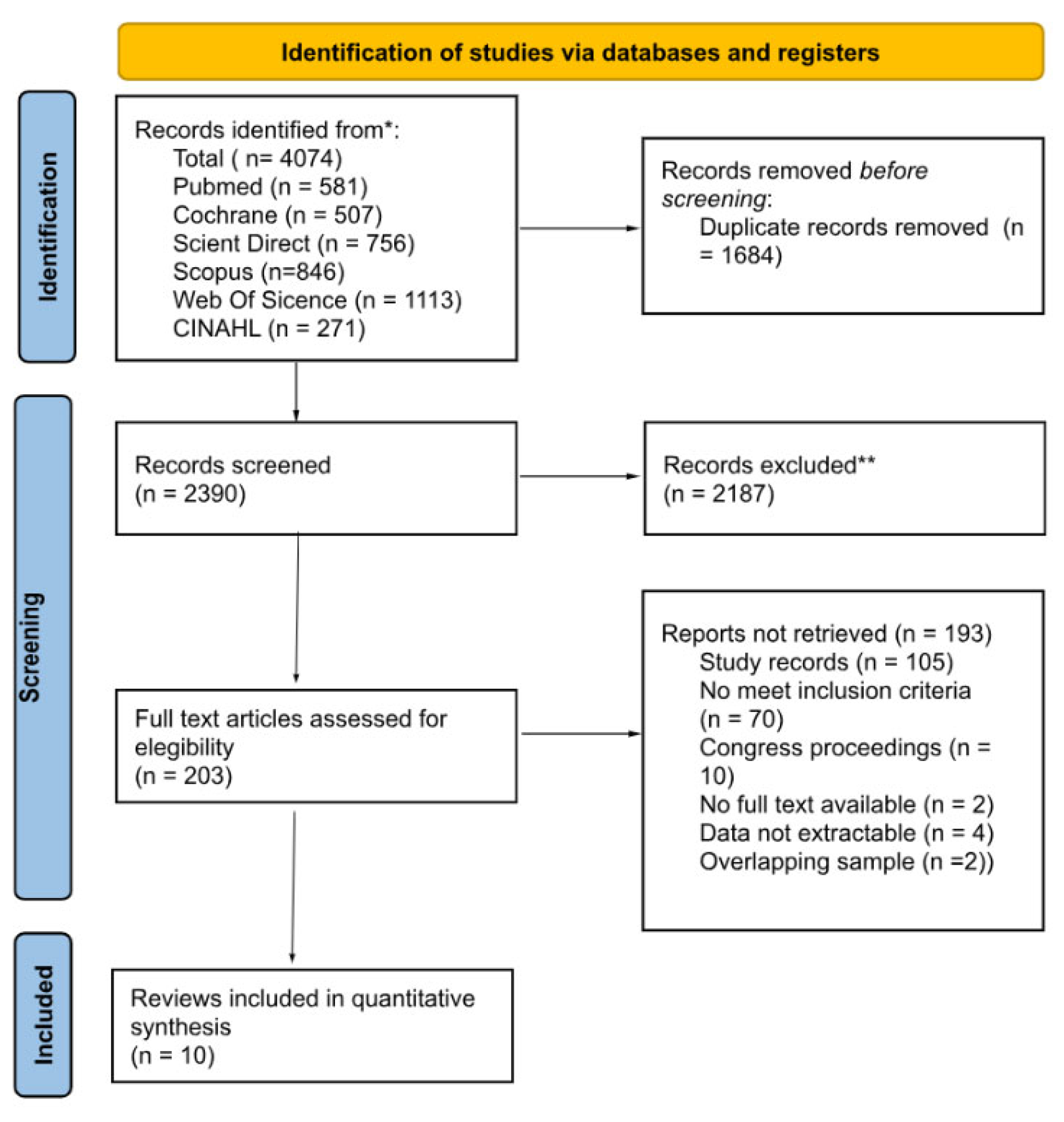

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

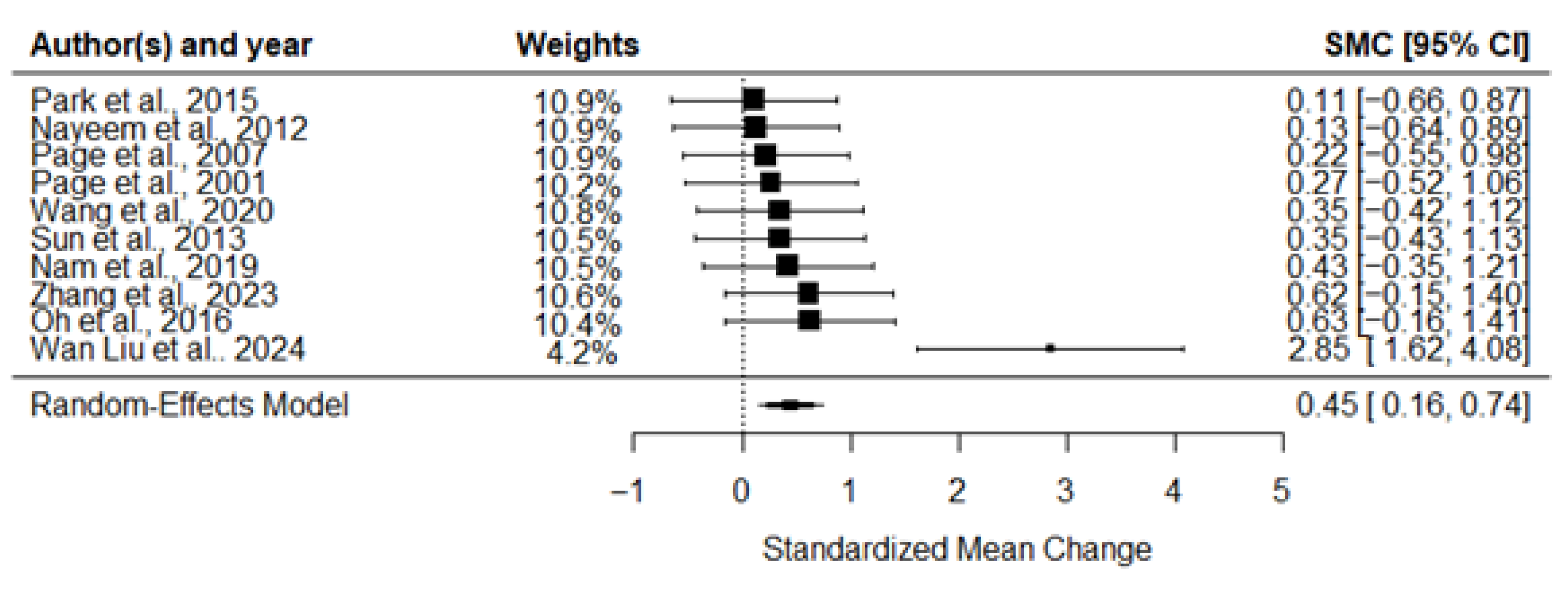

3.3. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of MI on Motor Recovery

3.4. Methodological Quality

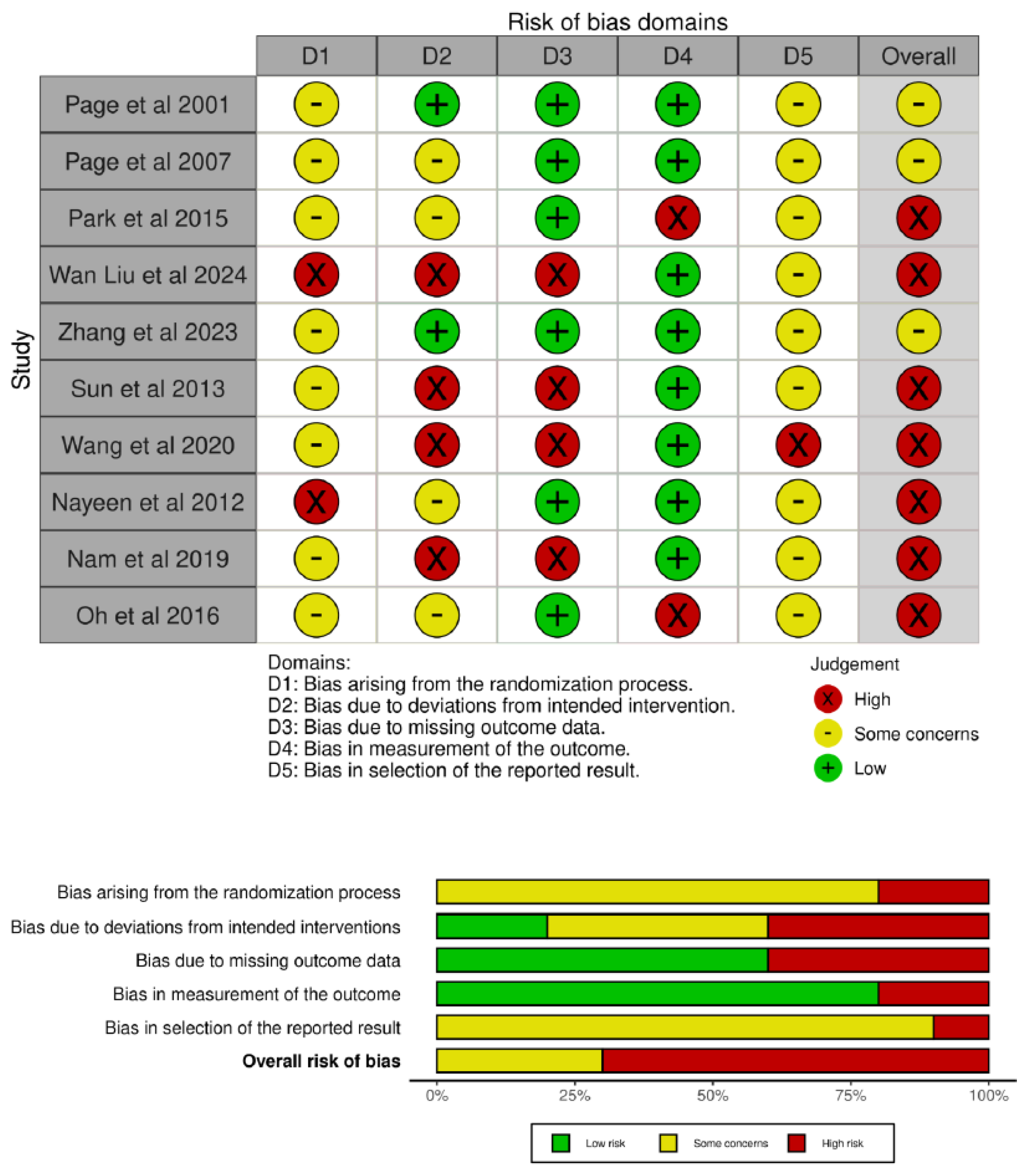

3.5. Risk of Bias

3.6. Overall Quality of Evidence

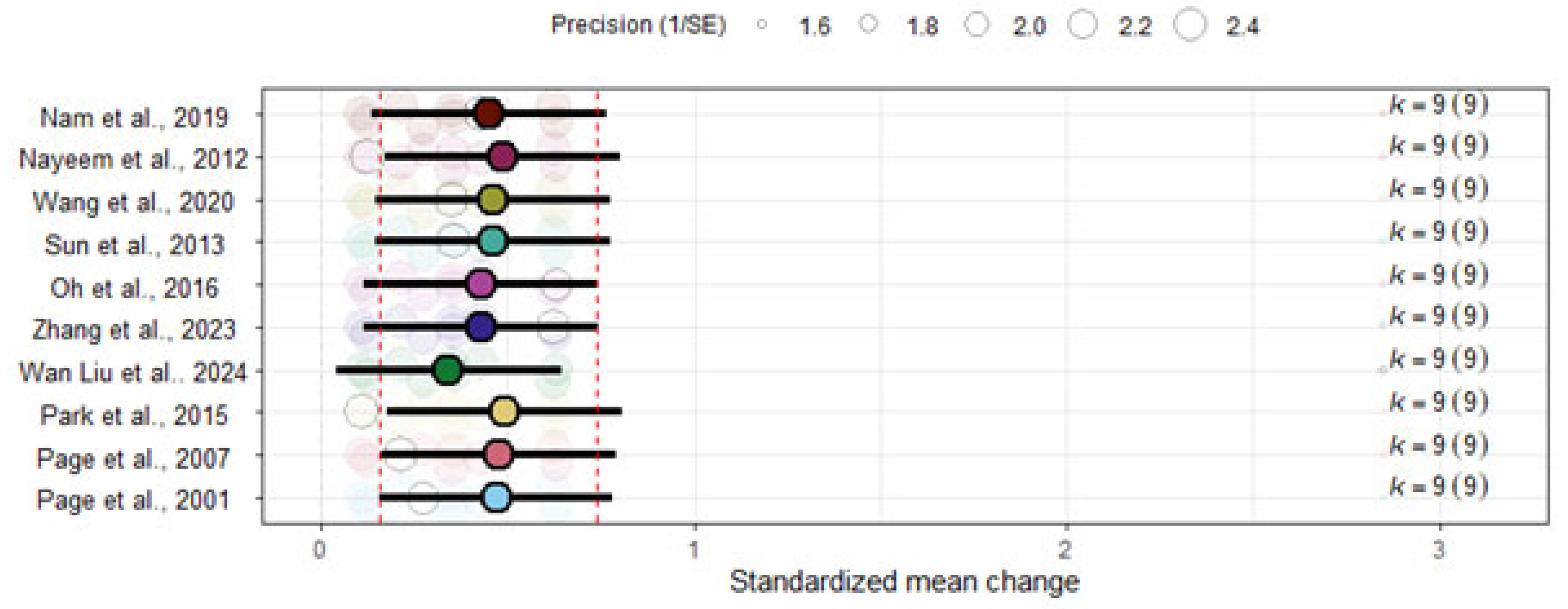

3.7. Sensitivity Analyses

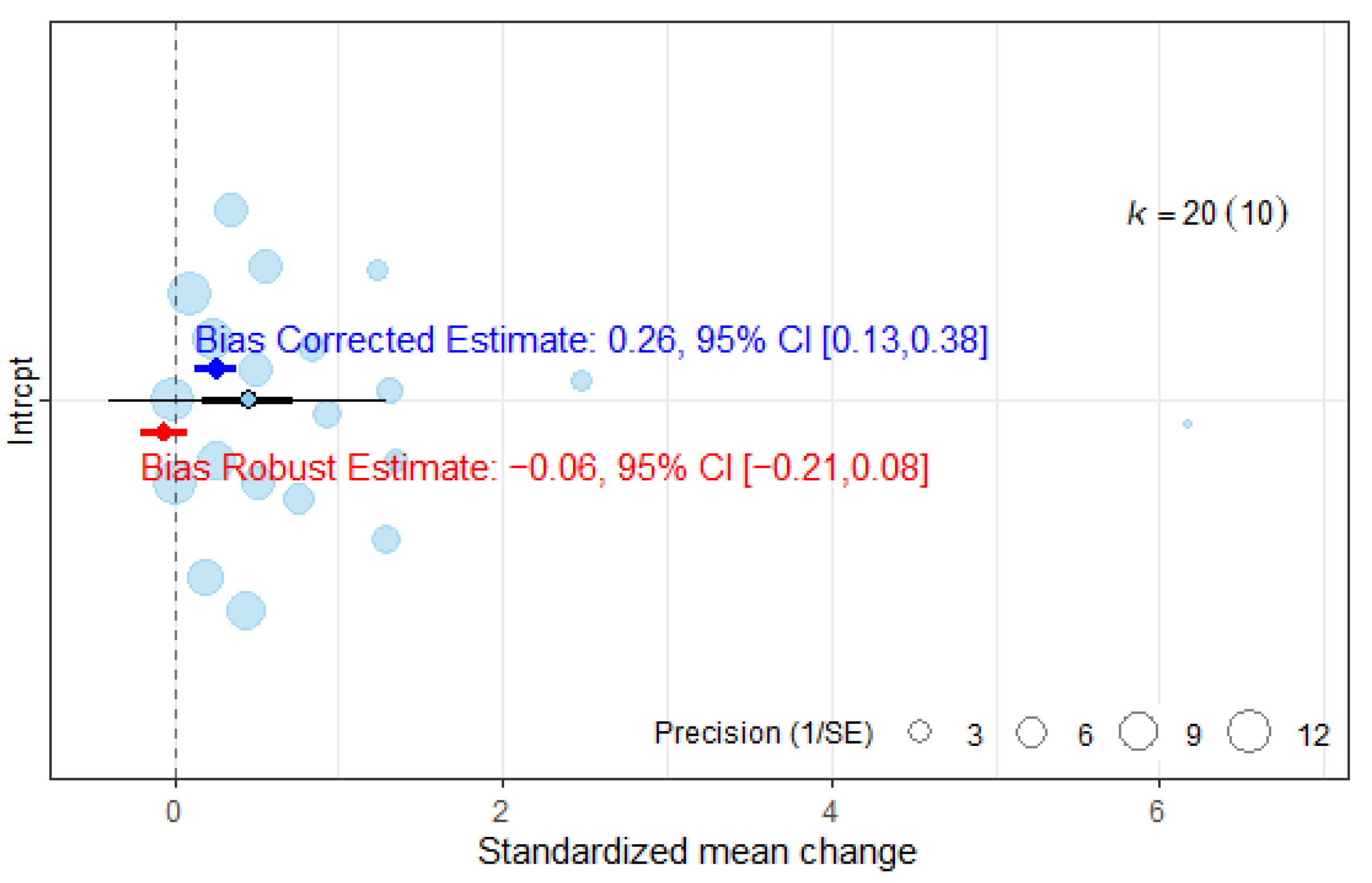

3.8. Publication Bias Analyses

3.9. Moderator Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings and Clinical Relevance

4.2. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

4.3. Future Research Directions

4.4. Clinical Implications and Final Remarks

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARAT | Action Research Arm Test |

| BBT | Box and Block Test |

| BCI-FES | Brain–Computer Interface with Functional Electrical Stimulation |

| CG | Control Group |

| CRT | Conventional Rehabilitation Therapy |

| ES | Effect Size |

| FM | Fugl-Meyer Assessment |

| FM-UE | Fugl-Meyer Assessment—Upper Extremity |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| fNIRS | Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| IG | Intervention Group |

| I2 | I-squared heterogeneity statistic |

| MCID | Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| MI | Motor Imagery |

| MP | Mental Practice |

| NIBS | Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation |

| PEDro | Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

| SMC | Standardized Mean Change |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

References

- Ferrari, A.J.; Santomauro, D.F.; Aali, A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbastabar, H.; ElHafeez, S.A.; Abdelmasseh, M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Chu, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Tang, J.; Xu, L.; Ni, W.; Tan, L.; Chen, Y. Progress in the application of motor imagery therapy in upper limb motor function rehabilitation of stroke patients with hemiplegia. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1454499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, L.A.; Butler, A.A.; Lord, S.R.; Gandevia, S.C. Use of a physiological profile to document upper limb motor impairment in ageing and in neurological conditions. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyle, R.C. A performance test for assessment of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and research. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 1981, 4, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.L.; Catlin, P.A.; Ellis, M.; Archer, A.L.; Morgan, B.; Piacentino, A. Assessing Wolf motor function test as outcome measure for research in patients after stroke. Stroke 2001, 32, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uswatte, G.; Taub, E.; Morris, D.; Light, K.; Thompson, P.A. The Motor Activity Log-28: Assessing daily use of the hemiparetic arm after stroke. Neurology 2006, 67, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santisteban, L.; Térémetz, M.; Bleton, J.P.; Baron, J.C.; Maier, M.A.; Lindberg, P.G. Upper limb outcome measures used in stroke rehabilitation studies: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, C.; Bettger, J.P.; Cockroft, K.M.; Cramer, S.C.; Edelen, M.O.; Hanley, D.; Katzan, I.L.; Mattke, S.; Nilsen, D.M.; Piquado, T.; et al. Chronic stroke outcome measures for motor function intervention trials: Expert panel recommendations. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2015, 8, S163–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blas-Zamorano, P.; Montagut-Martínez, P.; Pérez-Cruzado, D.; Merchan-Baeza, J.A. Fugl-Meyer Assessment for upper extremity in stroke: A psychometric systematic review. J. Hand Ther. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claflin, E.S.; Krishnan, C.; Khot, S.P. Emerging treatments for motor rehabilitation after stroke. Neurohospitalist 2015, 5, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-H.; Sung, W.-H.; Chiang, S.-L.; Lu, L.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Tung, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-H. Bimanual coordination deficits in hands following stroke and their relationship with motor and functional performance. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, L.; Theuns, P.; Dejaeger, E.; Devos, S.; Gantenbein, A.R.; Kerckhofs, E.; Schuback, B.; Schupp, W.; Putman, K. Long-term impact of stroke on patients' health-related quality of life. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprigio, D.; Bittencourt, J.; Ramim, M.; Marinho, V.; Brauns, I.; Fernandes, I.; Ribeiro, P.; Velasques, B.; Silva, A.C.A.E. Can mental practice adjunct in the recovery of motor function in the upper limbs after stroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Circ. 2022, 8, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, J.; Chitravas, N.; Meslo, I.L.; Thrift, A.G.; Indredavik, B. Not all stroke units are the same: A comparison of physical activity patterns in Melbourne, Australia, and Trondheim, Norway. Stroke 2008, 39, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, R.E.; Stevenson, T.J.; Poluha, W.; Semenko, B.; Schubert, J. Mental practice for treating upper extremity deficits in individuals with hemiparesis after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD005950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, A.Y.; Liu, K.P.Y.; Chung, R.C.K. Meta-analysis on the effect of mental imagery on motor recovery of the hemiplegic upper extremity function. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2014, 61, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Berges, E.; Soriano, A.A.L.; Lucha-López, O.; Tricas-Moreno, J.M.; Hernández-Secorún, M.; Gómez-Martínez, M.; Hidalgo-García, C. Motor imagery and mental practice in the subacute and chronic phases in upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: A systematic review. Occup. Ther. Int. 2023, 2023, 3752889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Okamura, R.; Moriuchi, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Higashi, T.; Tomori, K. Exploring methodological issues in mental practice for upper-extremity function following stroke-related paralysis: A scoping review. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Dunning, K.; Hermann, V.; Leonard, A.; Levine, P. Longer versus shorter mental practice sessions for affected upper extremity movement after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillwell, S.B.; Fineout-Overholt, E.; Melnyk, B.M.; Williamson, K.M. Popping the (PICO) question in research and evidence-based practice. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2002, 15, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, S.J.; Fulk, G.D.; Boyne, P. Clinically important differences for the upper-extremity Fugl-Meyer scale in people with minimal to moderate impairment due to chronic stroke. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jane, M.B.; Harlow, T.J.; Khu, E.C.; Shah, S.; Gould, A.T.; Veiner, E.; Kuo, Y.-J.; Hsu, C.-W.; Johnson, B.T. Extracting Pre-Post Correlations for Meta-Analyses of Repeated Measures Designs. Available online: https://matthewbjane.quarto.pub/pre-post-correlations/index.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Philips, G.R.; Daly, J.J.; Príncipe, J.C. Topographical measures of functional connectivity as biomarkers for post-stroke motor recovery. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, A.G.; McAuley, J.H. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. J. Physiother. 2020, 66, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, T.M.; Richter, R.R.; Sebelski, C.A. Introduction to the GRADE approach for guideline development: Considerations for physical therapist practice. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 tests. Biometrics 1954, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weights in Models Fitted with the rma.mv() Function [The Metafor Package]. Available online: https://www.metafor-project.org/doku.php/tips:weights_in_rma.mv_models (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Lagisz, M.; O'DEa, R.E.; Rutkowska, J.; Yang, Y.; Noble, D.W.A.; Senior, A.M. The orchard plot: Cultivating a forest plot for use in ecology, evolution, and beyond. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Botella, J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lagisz, M.; Williams, C.; Noble, D.W.A.; Pan, J.; Nakagawa, S. Robust point and variance estimation for meta-analyses with selective reporting and dependent effect sizes. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2024, 15, 1593–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aert, R.C.M.; Wicherts, J.M. Correcting for outcome reporting bias in a meta-analysis: A meta-regression approach. Behav. Res. Methods 2024, 56, 1994–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, F.; Winters, M.; Delahunt, E.; Elbers, R.; Lura, C.B.; Khan, K.M.; Weir, A.; Ardern, C.L. Identifying the ‘incredible’! Part 1: Assessing the risk of bias in outcomes included in systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Clayton, G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Savović, J. Empirical evidence of study design biases in randomized trials: Systematic review of meta-epidemiological studies. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Files Neuropsicología y Envejecimiento—SABIEX: Programa Integral Para Mayores de 55 Años en la UMH Para la Promoción del Envejecimiento Activo y Saludable. Available online: https://sabiex.umh.es/lineas-de-investigacion/neuropsicologia-y-envejecimiento-files/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Nam, J.S.; Yi, T.I.; Moon, H.I. Effects of adjuvant mental practice using inverse video of the unaffected upper limb in subacute stroke: A pilot randomized controlled study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2019, 42, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.S.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.J. Effects of adjuvant mental practice on affected upper limb function following a stroke: Results of three-dimensional motion analysis, Fugl-Meyer assessment of the upper extremity and motor activity logs. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 40, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, X.; Rao, J.; Yu, J.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Liu, L.; Gao, R. Motor imagery therapy improved upper limb motor function in stroke patients with hemiplegia by increasing functional connectivity of sensorimotor and cognitive networks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1295859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Levine, P.; Leonard, A. Mental practice in chronic stroke: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Stroke 2007, 38, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, N.; Cho, M.; Kim, D.J.; Yang, Y. Effects of mental practice on stroke patients’ upper extremity function and daily activity performance. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Yin, D.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, M.; Zang, L.; Wu, Y.; Jia, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, B.; Hu, Y. Cortical reorganization after motor imagery training in chronic stroke patients with severe motor impairment: A longitudinal fMRI study. Neuroradiology 2013, 55, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Xiong, X.; Sun, C.; Zhu, B.; Xu, Y.; Fan, M.; Tong, S.; Sun, L.; Guo, X. Motor imagery training after stroke increases slow-5 oscillations and functional connectivity in the ipsilesional inferior parietal lobule. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayeem, Z.; Majumi, M.N.; Fyzail, A. Effect of Mental Imagery on Upper Extremity Function in Stroke Patients. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268814690_Effect_of_Mental_Imagery_on_Upper_Extremity_Function_in_Stroke_Patients (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Page, S.J.; Levine, P.; Sisto, S.A.; Johnston, M.V. A randomized efficacy and feasibility study of imagery in acute stroke. Clin. Rehabil. 2001, 15, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Xiong, X.; Tong, S.; Sun, C.; Zhu, B.; Xu, Y.; Fan, M.; Sun, L.; et al. Neuroimaging prognostic factors for treatment response to motor imagery training after stroke. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 9504–9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I.; Guittet, L.; Estellat, C.; Moher, D.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Ravaud, P. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Terrin, N.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rücker, G.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltra-Cucarella, J.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Clare, L.; Morris, S.B.; Espert, R.; Tirapu, J.; Sánchez-SanSegundo, M. Differential effects of cognition-focused interventions for people with Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology 2018, 32, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiragami, S.; Inoue, Y.; Harada, K. Minimal clinically important difference for the Fugl-Meyer assessment of the upper extremity in convalescent stroke patients with moderate to severe hemiparesis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2019, 31, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, J.; Dodakian, L.; Chou, C.; Chan, V.; McKenzie, A.; Reinkensmeyer, D.J.; Cramer, S.C. A standardized approach to the Fugl-Meyer assessment and its implications for clinical trials. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2013, 27, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwakkel, G.; Kollen, B. Predicting improvement in the upper paretic limb after stroke: A longitudinal prospective study. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioni, A.; Raho, E.M.; Straudi, S.; Granieri, E.; Koch, G.; Fadiga, L. The cerebellum and the mirror neuron system: A matter of inhibition? From neurophysiological evidence to neuromodulatory implications. A narrative review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 164, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowering, K.J.; O'COnnell, N.E.; Tabor, A.; Catley, M.J.; Leake, H.B.; Moseley, G.L.; Stanton, T.R. The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain 2013, 14, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Bermejo-Bernardez-Zerpa, A.; Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Lucena-Anton, D.; Luque-Moreno, C. Effectiveness of motor imagery on motor recovery in patients with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caligiore, D.; Mustile, M.; Spalletta, G.; Baldassarre, G. Action observation and motor imagery for rehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and an integrative hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 72, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y. Brain plasticity and rehabilitation in stroke patients. J. Nippon. Med. Sch. 2015, 82, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Chang, W.H.; Lee, M.; Kwon, G.H.; Kim, L.; Kim, S.T.; Kim, Y.H. Predicting the performance of motor imagery in stroke patients: Multivariate pattern analysis of functional MRI data. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouin, F.; Richards, C.L.; Durand, A.; Doyon, J. Reliability of mental chronometry for assessing motor imagery ability after stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, H.L.; Le, T.H.; Lim, J.M.; Hwang, C.H.; Koo, K.I. Effectiveness of augmented reality in stroke rehabilitation: A meta-analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Ku, J.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, Y.J. Virtual reality-guided motor imagery increases corticomotor excitability in healthy volunteers and stroke patients. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 40, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Zeng, F.; Tang, Y.; Shi, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. The clinical effects of brain-computer interface with robot on upper-limb function for post-stroke rehabilitation: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Fares, H.; Ghayvat, H.; Brunner, I.C.; Puthusserypady, S.; Razavi, B.; Lansberg, M.; Poon, A.; Meador, K.J. A systematic review on functional electrical stimulation-based rehabilitation systems for upper limb post-stroke recovery. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1272992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Lv, P.; Yin, Y. Examining the effectiveness of motor imagery combined with non-invasive brain stimulation for upper limb recovery in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioni, A.; Galluccio, M.; Toselli, R.; Baroni, A.; Fregna, G.; Schincaglia, N.; Milani, G.; Cosma, M.; Ferraresi, G.; Morelli, M.; et al. A multimodal analysis to explore upper limb motor recovery at 4 weeks after stroke: Insights from EEG and kinematics measures. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2024, 55, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Li, S.; Roh, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. Multimodal neuroimaging using concurrent EEG/fNIRS for poststroke recovery assessment: An exploratory study. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, S.C.; Wolf, S.L.; Adams, H.P.; Chen, D.; Dromerick, A.W.; Dunning, K.; Ellerbe, C.; Grande, A.; Janis, S.; Lansberg, M.G.; et al. Stroke recovery and rehabilitation research: Issues, opportunities, and the National Institutes of Health StrokeNet. Stroke 2017, 48, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Design | Phase Stroke | Etiology | Lesion laterality | Severity FM-UE | Groups | Age | Intervention | Intervention volume | Outcomes | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks | Frequency | Session Duration (Minutes) | ||||||||||||

| [43] | Pilot RCT | Subacute | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Severe | IG (12) | 61.8 | MP combined with CRT (proprioceptive exercises, gait training, hand and wrist mobilization, stretching, weight bearing, strengthening, and functional task practice). | 4 | 5 | MI: 20 CRT: 30 | 6FM-UE MFT FIM | No significant differences were found between MP plus CRT alone in subacute post-stroke patients. | |

| Severe | CG (12) | 59.6 | CRT | 4 | 5 | 30 | ||||||||

| [50] | RCT | Chronic | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Near Normal | IG (15) | 47.5 | MI with the imagery guided by an audio tape and CRT. | 3 | 4 | MI: 15 CRT: 15 | MAL-AOU MAL-QOM FM-UE | Participation in a MI protocol can improve the upper extremity function in chronic stroke patients. | |

| Near Normal | CG (15) | 50.1 | CRT | 3 | 4 | 15 | ||||||||

| [44] | Crossover | Subacute | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Mild | IG (5) | 57.9 | MP protocol including two tasks (drinking from a cup and opening a door) in addition to CRT. | 3 | MI: 3 CRT: 5 | MI: 20 CRT: 30 | FM-UE MAL-AOU MAL-QOM 3D motion analysis | Adjuvant MP showed no significant effects on upper limb function after stroke. | |

| Mild | CG (5) | 57.9 | CRT. | 3 | 5 | 30 | ||||||||

| [51] | RCT | Subacute and chronic | Ischaemic | Both | Moderate | IG (8) | 64.4 | CRT including upper and lower limb exercises, transfers, balance/walking training, and activities of daily living performed bimanually, combined with guided MI sessions after each therapy. | 6 | 3 | MI: 10 CRT: 60 | FM-UE ARAT | MI was a feasible and cost-effective complement to therapy, improving outcomes compared to therapy alone. | |

| Moderate | CG (5) | 65.0 | CR including the same program of upper and lower limb exercises, transfers, balance/walking training, and activities of daily living | 6 | 3 | 60 | ||||||||

| [46] | RCT | Chronic | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Moderate | IG (16) | 58.7 | CRT focused on activities of daily living, combined with daily MP sessions directly after therapy. | 6 | 2 | MI: 30 CRT: 30 | FM-UE ARAT | MP programs significantly improved arm motor function in chronic stroke patients. | |

| Moderate | CG (16) | 60.4 | CRT with equal therapist interaction. | 6 | 2 | CRT: 30 | ||||||||

| [47] | RCT | Chronic | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Right hemisferic | Moderate | IG (14) | 60 | MI focused on daily tasks (e.g., page turning, bean transfer, cup stacking) and CRT. | 2 | 5 | MI:10 CRT: 30 | ARAT FM-UE MBI | MI improved upper extremity function and daily activity performance in stroke patients. | |

| Low—Moderate | CG (15) | 58 | CRT. | 2 | 5 | 30 | ||||||||

| [48] | RCT | Chronic | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Severe | IG (9) | 56.7 | Standard CRT —including physical and occupational therapy, electrical stimulation, acupuncture, and massage—supplemented with MI training. | 4 | 5 | MI:30 CRT: 180 | FM-UE | MI induced cortical reorganization in chronic stroke patients, supporting motor function improvement. | |

| Severe | CG (9) | 56.1 | Standard CRT | 4 | 5 | 180 | ||||||||

| [45] | RCT | Subacute | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Severe | IG (13) | 58.6 | CRT (physical therapy, occupational therapy, electrical stimulation, and Chinese acupuncture) plus specific MI training | 4 | 5 | MI: 30 CRT: 120 | MBI FM-UE | MI training combined with CRT significantly improved upper limb function and daily activities compared to rehabilitation alone. | |

| Severe | CG (13) | 60.2 | CRT (physical therapy, occupational therapy, electrical stimulation, and Chinese acupuncture) | 4 | 5 | 120 | ||||||||

| [49] | RCT | Chronic | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Severe | IG (17) | 53.4 | CRT supplemented with supervised MI training of the affected upper limb—including relaxation, basic movements, and goal-directed daily activities | 4 | 5 | MI:30 CRT: 180 | FM-UE MBI fMRI | MI training significantly improved FM-UE compared to CG, accompanied by increased fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (slow-5) and altered functional connectivity in the ipsilesional inferior parietal lobule, both correlated with motor recovery. | |

| Severe | CG (17) | 60.5 | CRT | 4 | 5 | CRT: 180 | ||||||||

| [52] | RCT | Subacute and chronic | Ischaemic and haemorrhagic | Both | Severe | IG (22) | 54.4 | MI of the upper limb with first-person practice of movements and daily activities, added to CRT (physical therapy, occupational therapy, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, and acupuncture). | 4 | 5 | MI: 30 CRT 180 | MBI FM-UE | MI training improved motor recovery beyond CRT, with greater benefits in patients with impaired motor planning but preserved motor imagery ability. | |

| Severe | CG (17) | 59.7 | CRT included physical therapy, occupational therapy, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, and Chinese acupuncture. | 4 | 5 | CRT: 180 | ||||||||

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| [46] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| [47] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 5 |

| [45] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 |

| [52] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| [44] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| [48] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 5 |

| [49] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 5 |

| [50] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| [43] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Studies | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | SMD (95% CI) | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 RCTs (n = 255) | Very serious | Serious (I2 = 88.2%) | No serious | Serious | Very serious | ES = 0.45 (0.16, 0.74) Adjusted ES = −0.06 (−0.21, −0.08) | Very Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polo-Ferrero, L.; Torres-Alonso, J.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Hernández-Rubia, S.; Pérez-Elvira, R.; Oltra-Cucarella, J. Motor Imagery for Post-Stroke Upper Limb Recovery: A Meta-Analysis of RCTs on Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Scores. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217891

Polo-Ferrero L, Torres-Alonso J, Sánchez-González JL, Hernández-Rubia S, Pérez-Elvira R, Oltra-Cucarella J. Motor Imagery for Post-Stroke Upper Limb Recovery: A Meta-Analysis of RCTs on Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Scores. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217891

Chicago/Turabian StylePolo-Ferrero, Luis, Javier Torres-Alonso, Juan Luis Sánchez-González, Sara Hernández-Rubia, Rubén Pérez-Elvira, and Javier Oltra-Cucarella. 2025. "Motor Imagery for Post-Stroke Upper Limb Recovery: A Meta-Analysis of RCTs on Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Scores" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217891

APA StylePolo-Ferrero, L., Torres-Alonso, J., Sánchez-González, J. L., Hernández-Rubia, S., Pérez-Elvira, R., & Oltra-Cucarella, J. (2025). Motor Imagery for Post-Stroke Upper Limb Recovery: A Meta-Analysis of RCTs on Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Scores. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217891