Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Active Versus Inactive Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Data from the PRO-AOSD Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Patient and Public Involvement

2.4. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.1.1. Time to Diagnosis

3.1.2. Disease Activity Determined by CRP Levels and PGA Scores

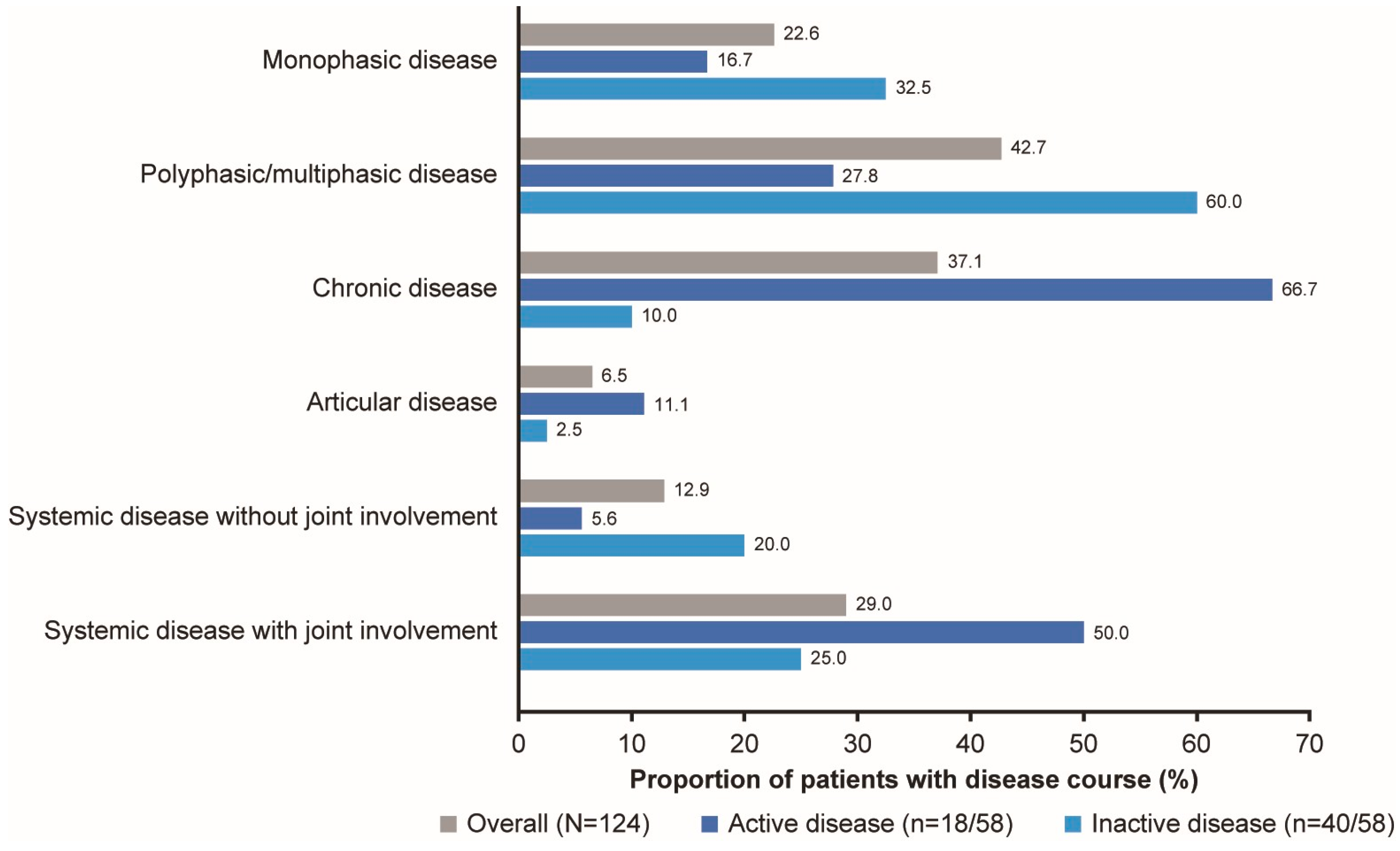

3.1.3. Disease Course

3.2. HRQoL

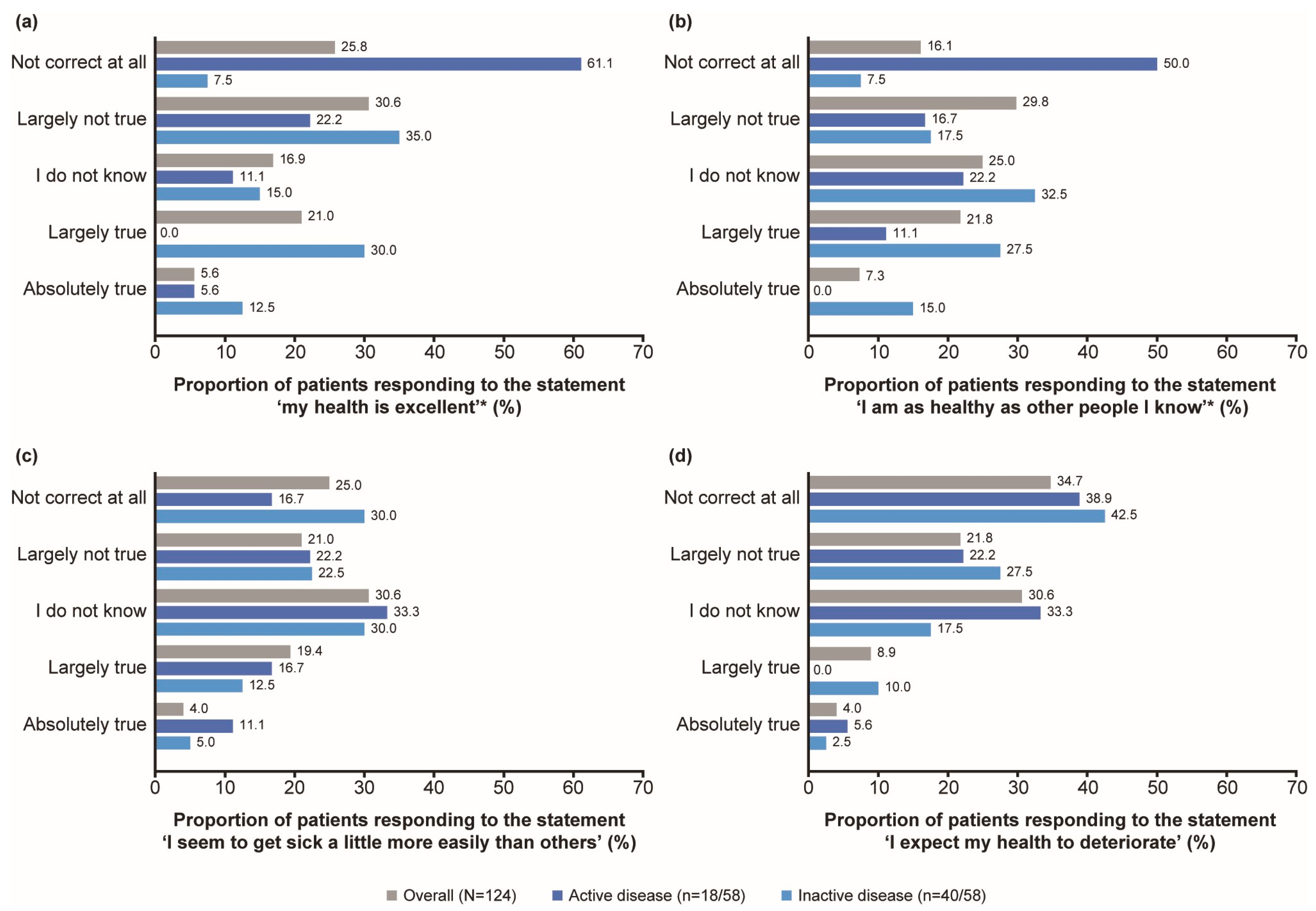

3.2.1. General State of Health

3.2.2. Pain

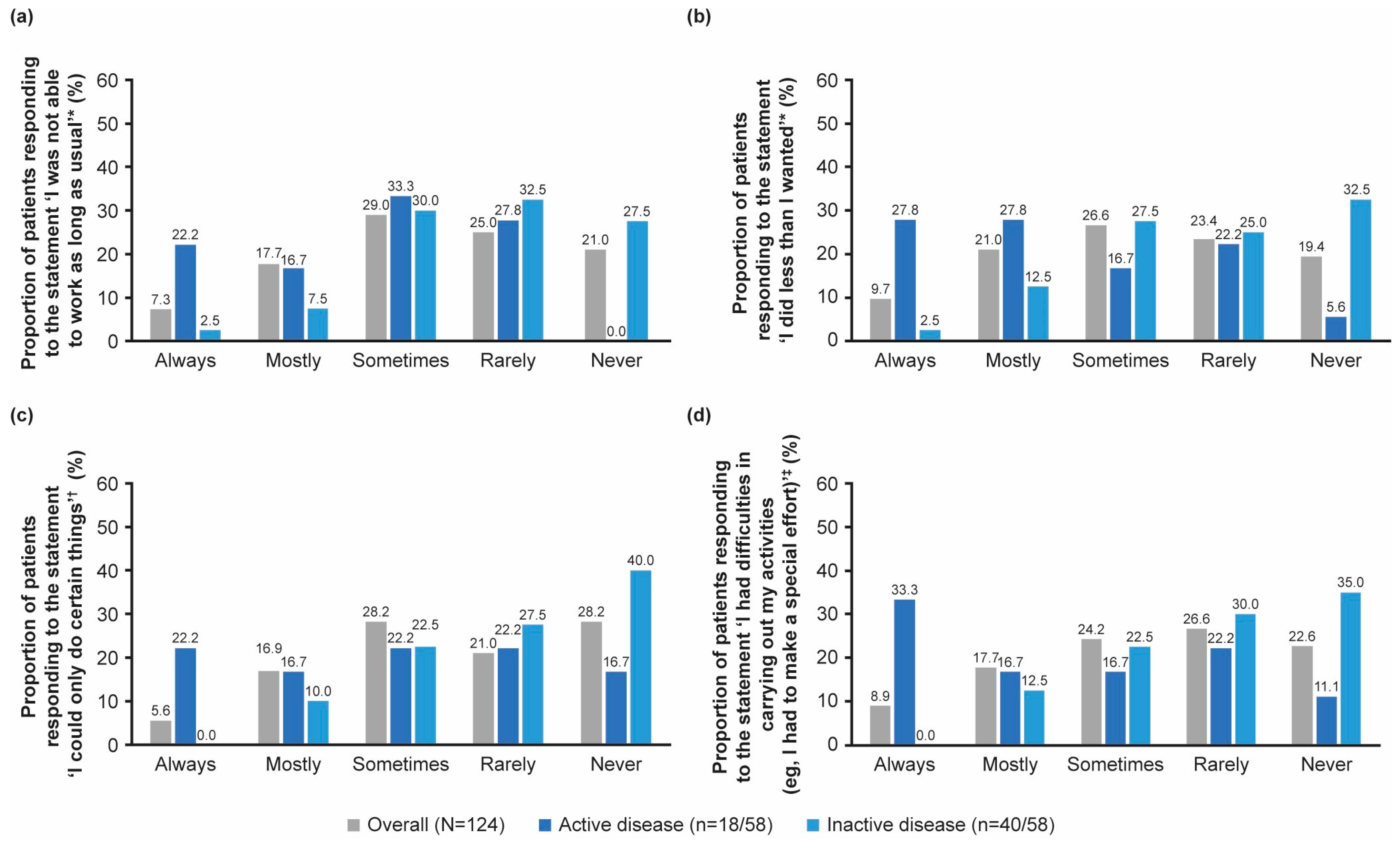

3.2.3. Physical Health

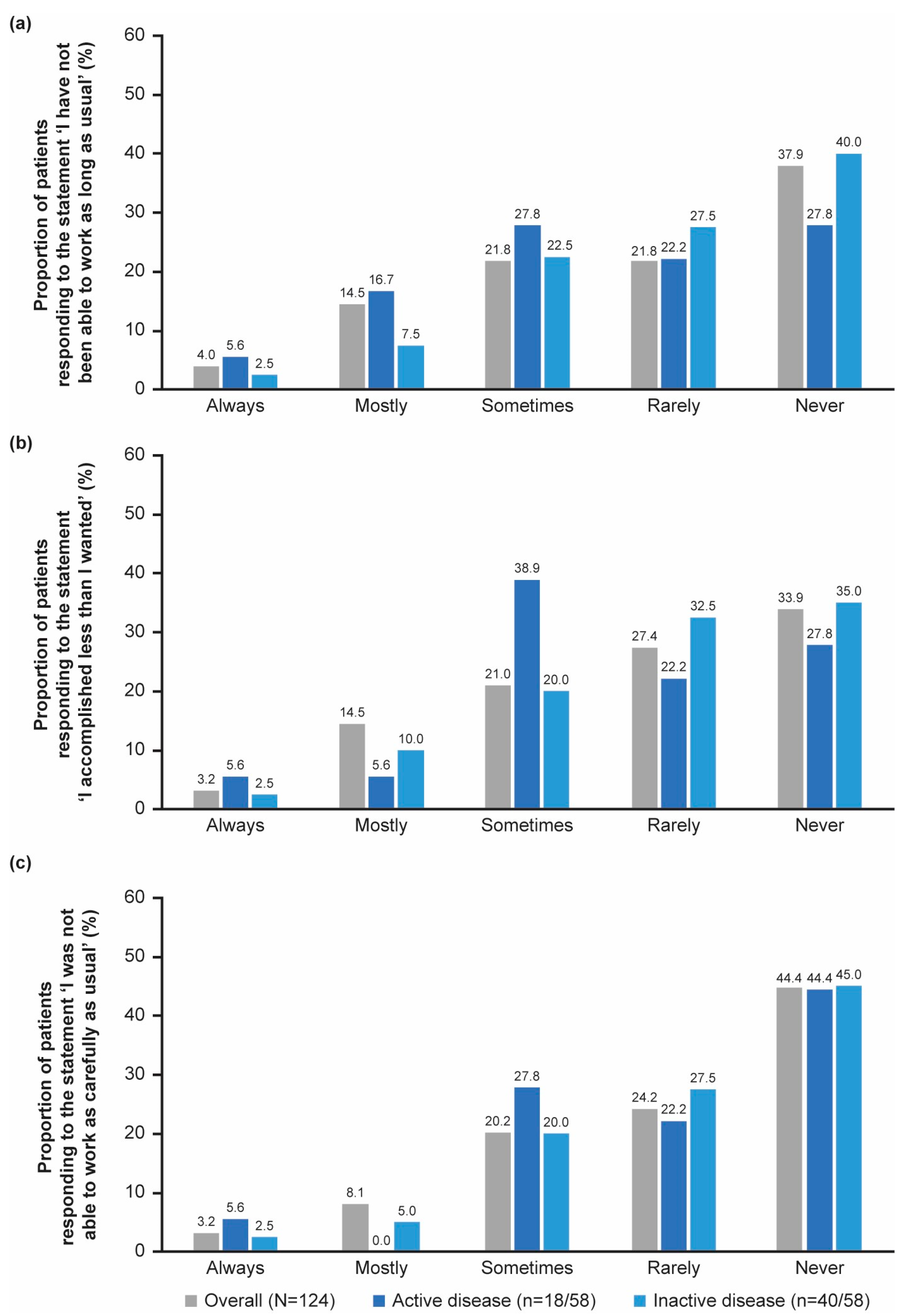

3.2.4. Mental Health and Vitality

3.3. Sleep

3.4. Work Productivity

3.5. Effects of COVID-19 on Patients with AOSD

3.5.1. General Health

3.5.2. Work Productivity

3.6. Patient Informedness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AID | Autoimmune disease |

| AOSD | Adult-onset Still’s disease |

| bDMARD | Biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus 2019 |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CS | Corticosteroids |

| csDMARD | Conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs |

| DMARD | Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| N/n | Number of patients |

| PGA | Physician’s Global Assessment of disease activity |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcomes |

| PRO-AOSD | Patient-reported outcomes adult-onset Still’s disease |

| SF-36v2 | Short Form 36-item Health Survey version 2 |

| sJIA | Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Fet-He, S.; Ibarra Lecompte, G.; Quiroz Alfaro, A.J. Association between adult-onset still’s disease and COVID-19: A report of two cases and brief review. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2024, 12, 2050313x241233197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavis, H.L.; van Daele, P.L.A.; Mulders-Manders, C.; Michels, R.; Rutgers, A.; Legger, E.; Bijl, M.; Hak, E.A.; Lam-Tse, W.-K.; Bonte-Mineur, F.; et al. Management of adult-onset Still’s disease: Evidence- and consensus-based recommendations by experts. Rheumatology 2023, 63, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, P.; McGonagle, D.; Garcia, V.C.; Rabijns, H.; Toennessen, K.; Chappell, M.; Edwards, M.; Miller, P.; Hansell, N.; Moss, J.; et al. Systematic review and metaanalysis of pharmacological interventions in adult-onset Still disease and the role of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 51, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vordenbaumen, S.; Feist, E.; Rech, J.; Fleck, M.; Blank, N.; Haas, J.P.; Kotter, I.; Krusche, M.; Chehab, G.; Hoyer, B.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adult-onset Still’s disease: A concise summary of the German society of Rheumatology S2 guideline. Z. Rheumatol. 2023, 82, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthimiou, P.; Kontzias, A.; Hur, P.; Rodha, K.; Ramakrishna, G.S.; Nakasato, P. Adult-onset Still’s disease in focus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and unmet needs in the era of targeted therapies. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 51, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautrel, B.; Mitrovic, S.; De Matteis, A.; Bindoli, S.; Antón, J.; Belot, A.; Bracaglia, C.; Constantin, T.; Dagna, L.; Di Bartolo, A.; et al. EULAR/PReS recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Still’s disease, comprising systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still’s disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, P.; Cipriani, P.; Iacono, D.; Pantano, I.; Caso, F.; Emmi, G.; Grembiale, R.D.; Cantatore, F.P.; Atzeni, F.; Perosa, F.; et al. Ferritin and C-reactive protein are predictive biomarkers of mortality and macrophage activation syndrome in adult onset Still’s disease. Analysis of the multicentre Gruppo Italiano di Ricerca in Reumatologia Clinica e Sperimentale (GIRRCS) cohort. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.-y.; Yao, Y.-m. The Clinical Significance and Potential Role of C-Reactive Protein in Chronic Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Potempa, L.A.; El Kebir, D.; Filep, J.G. C-reactive protein and inflammation: Conformational changes affect function. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, A.; Giancane, G.; Naddei, R.; Natoli, V.; Ridella, F.; Burrone, M.; Rosina, S.; Chedeville, G.; Alexeeva, E.; Horneff, G.; et al. Drivers of non-zero physician global scores during periods of inactive disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. RMD Open 2022, 8, e002042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruperto, N.; Ravelli, A.; Falcini, F.; Lepore, L.; Buoncompagni, A.; Gerloni, V.; Bardare, M.; Cortis, E.; Zulian, F.; Sardella, M.L.; et al. Responsiveness of outcome measures in juvenile chronic arthritis. Italian Pediatric Rheumatology Study Group. Rheumatology 1999, 38, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Moretti, C.; Viola, S.; Pistorio, A.; Magni-Manzoni, S.; Ruperto, N.; Martini, A.; Ravelli, A. Relative responsiveness of condition specific and generic health status measures in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscitti, P.; Rozza, G.; Di Muzio, C.; Biaggi, A.; Iacono, D.; Pantano, I.; Iagnocco, A.; Giacomelli, R.; Cipriani, P.; Ciccia, F. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with adult onset Still disease: Results from a multicentre cross-sectional study. Medicine 2022, 101, e29540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, B.R. Considerations for reporting and reviewing studies including health-related quality of life. Chest 2020, 158, S49–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Di Carlo, M.; Carotti, M.; Farah, S.; Ciapetti, A.; Gutierrez, M. The impact of different rheumatic diseases on health-related quality of life: A comparison with a selected sample of healthy individuals using SF-36 questionnaire, EQ-5D and SF-6D utility values. Acta Biomed. 2019, 89, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Jin, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, T.; Zeng, T.; Shi, H.; Wu, X.; Wan, L.; Teng, J.; Sun, Y.; et al. Anxiety and depression in adult-onset Still’s disease patients and associations with health-related quality of life. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 3723–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, P.; Feist, E.; Canon-Garcia, V.; Rabijns, H.; Toennessen, K.; Bartlett, C.; Gregg, E.; Miller, P.; McGonagle, D. Burden of adult-onset Still’s disease: A systematic review of health-related quality of life, utilities, costs and resource use. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2023, 63, 152264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Mavragani, C.P. COVID-19 in autoimmune rheumatic diseases: Lessons learned and emerging risk stratification approaches. J. Immunol. Sci. 2025, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wang, X.; Dai, N.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Cheng, X.; Ye, J.; Shi, H.; Hu, Q.; Meng, J.; et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 and impact of disease activity in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease. Rheumatol. Ther. 2024, 11, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.C.; Alves, L.R.; Soares, J.M.P.; Souza, S.K.A.; Silva, B.M.R.; Fonseca, A.L.; Silva, C.H.M.; Oliveira, C.S.; Vieira, R.P.; Oliveira, D.A.A.P.; et al. Health-related quality of life and functional status of post-COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, R.; Kim, A.H.J.; Conway, R.; Yazdany, J.; Robinson, P.C. COVID-19 in people with rheumatic diseases: Risks, outcomes, treatment considerations. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.H.; Strand, V.; Oh, Y.J.; Song, Y.W.; Lee, E.B. Health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis compared with other rheumatic diseases: A cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Shao, R.; Han, X.; Su, C.; Lu, W. Risk and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases compared with the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, N.; Andreica, I.; Rech, J.; Sözen, Z.; Feist, E. Evaluating the divide between patients’ and physicians’ perceptions of adult-onset Still’s disease cases: Insights from the PRO-AOSD survey. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscitti, P.; Barile, A.; Berardicurti, O.; Iafrate, S.; Di Benedetto, P.; Vitale, A.; Caso, F.; Costa, L.; Bruno, F.; Ursini, F.; et al. The joint involvement in adult onset Still’s disease is characterised by a peculiar magnetic resonance imaging and a specific transcriptomic profile. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, B.O.; Altraide, D.D.; Otike-Odibi, B.I. Adult onset still’s disease: A rare disorder. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2841–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matcham, F.; Scott, I.C.; Rayner, L.; Hotopf, M.; Kingsley, G.H.; Norton, S.; Scott, D.L.; Steer, S. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 44, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucourt, E.; Martaillé, V.; Goupille, P.; Joncker-Vannier, I.; Huttenberger, B.; Réveillère, C.; Mulleman, D.; Courtois, A.R. A Comparative study of fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and Sjögren’s Syndrome; Impact of the disease on quality of life, psychological adjustment, and use of coping strategies. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, M.; Barańska, A.; Kanecki, K.; Karpińska, A.; Firlej, E.; Bogdan, M. Coping strategies observed in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampalis, J.S.; Esdaile, J.M.; Medsger, T.A., Jr.; Partridge, A.J.; Yeadon, C.; Senécal, J.L.; Myhal, D.; Harth, M.; Gutkowski, A.; Carette, S.; et al. A controlled study of the long-term prognosis of adult Still’s disease. Am. J. Med. 1995, 98, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, A.; Schranz, M.; Rexroth, U.; Hamouda, O.; Schaade, L.; Diercke, M.; Boender, T.S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated non-pharmaceutical interventions on other notifiable infectious diseases in Germany: An analysis of national surveillance data during week 1-2016-week 32-2020. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 6, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppert, A.; Polotzek, K.; Schmitt, J.; Busse, R.; Karschau, J.; Karagiannidis, C. Different spreading dynamics throughout Germany during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A time series study based on national surveillance data. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 6, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.H.Y.; Tay, S.H.; Cheung, P.P.M.; Santosa, A.; Chan, Y.H.; Yip, J.W.L.; Mak, A.; Lahiri, M. Attitudes and behaviors of patients with rheumatic diseases during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.M.; Elotla, S.F.; Elkaraly, N.E.; Mohamed, A.E. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: Disruptions in care and self-reported outcomes. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.; Diener, M.; Hueber, A.J.; Henes, J.; Krusche, M.; Ignatyev, Y.; May, S.; Erstling, U.; Elling-Audersch, C.; Knitza, J.; et al. Unmet information needs of patients with rheumatic diseases: Results of a cross-sectional online survey study in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeTora, L.M.; Toroser, D.; Sykes, A.; Vanderlinden, C.; Plunkett, F.J.; Lane, T.; Hanekamp, E.; Dormer, L.; DiBiasi, F.; Bridges, D.; et al. Good Publication Practice (GPP) Guidelines for company-sponsored biomedical research: 2022 Update. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Active Disease | Inactive Disease | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 124 (100%) | n = 18/58 (31.0%) | n = 40/58 (69.0%) | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 45.5 (14.7) | 46.5 (14.6) | 45.3 (12.3) | 0.754 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.05 | |||

| Female | 74 (59.7) | 12 (66.7) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Male | 50 (40.3) | 6 (33.3) | 25 (62.5) | |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 79.0 (19.1) | 79.3 (20.0) | 81.1 (17.7) | 0.749 |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 170.8 (9.9) | 171.2 (7.6) | 174.0 (9.1) | 0.237 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.0 (5.8) | 26.9 (6.3) | 26.7 (4.9) | 0.895 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 18.0 (14.5) | 2.0 (11.1) | 6.0 (15.0) | 1 |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 32.2 (14.8) † | 36.0 (18.2) | 38.6 (13.3) | 0.604 |

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| The COVID-19 pandemic puts more strain on me as an AOSD patient than on other healthy people and further restricts my quality of life | 42 (33.9) | 82 (66.1) |

| I am more afraid than my friends/acquaintances of contracting COVID-19 because of my AOSD condition | 61 (49.2) | 63 (50.8) |

| As an AOSD patient, I feel I am at higher risk of contracting severe COVID-19 | 77 (62.1) | 47 (37.9) |

| I feel uncomfortable going to the doctor or hospital and am afraid of contracting COVID-19 there | 40 (32.3) | 84 (67.7) |

| I am concerned that the medication I receive for my AOSD may weaken my immune system and put me at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 (n = 121) | 67 (55.4) | 54 (44.6) |

| In the past, I have stopped taking my medication to treat AOSD for this reason (n = 67) | 4 (6.0) | 63 (94.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blank, N.; Andreica, I.; Rech, J.; Sözen, Z.; Feist, E. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Active Versus Inactive Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Data from the PRO-AOSD Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217848

Blank N, Andreica I, Rech J, Sözen Z, Feist E. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Active Versus Inactive Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Data from the PRO-AOSD Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217848

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlank, Norbert, Ioana Andreica, Jürgen Rech, Zekayi Sözen, and Eugen Feist. 2025. "Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Active Versus Inactive Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Data from the PRO-AOSD Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217848

APA StyleBlank, N., Andreica, I., Rech, J., Sözen, Z., & Feist, E. (2025). Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Active Versus Inactive Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Data from the PRO-AOSD Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217848