Risk Factors and Clinical Significance of Urologic Injury in Cesarean Hysterectomy for Placenta Accreta Spectrum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

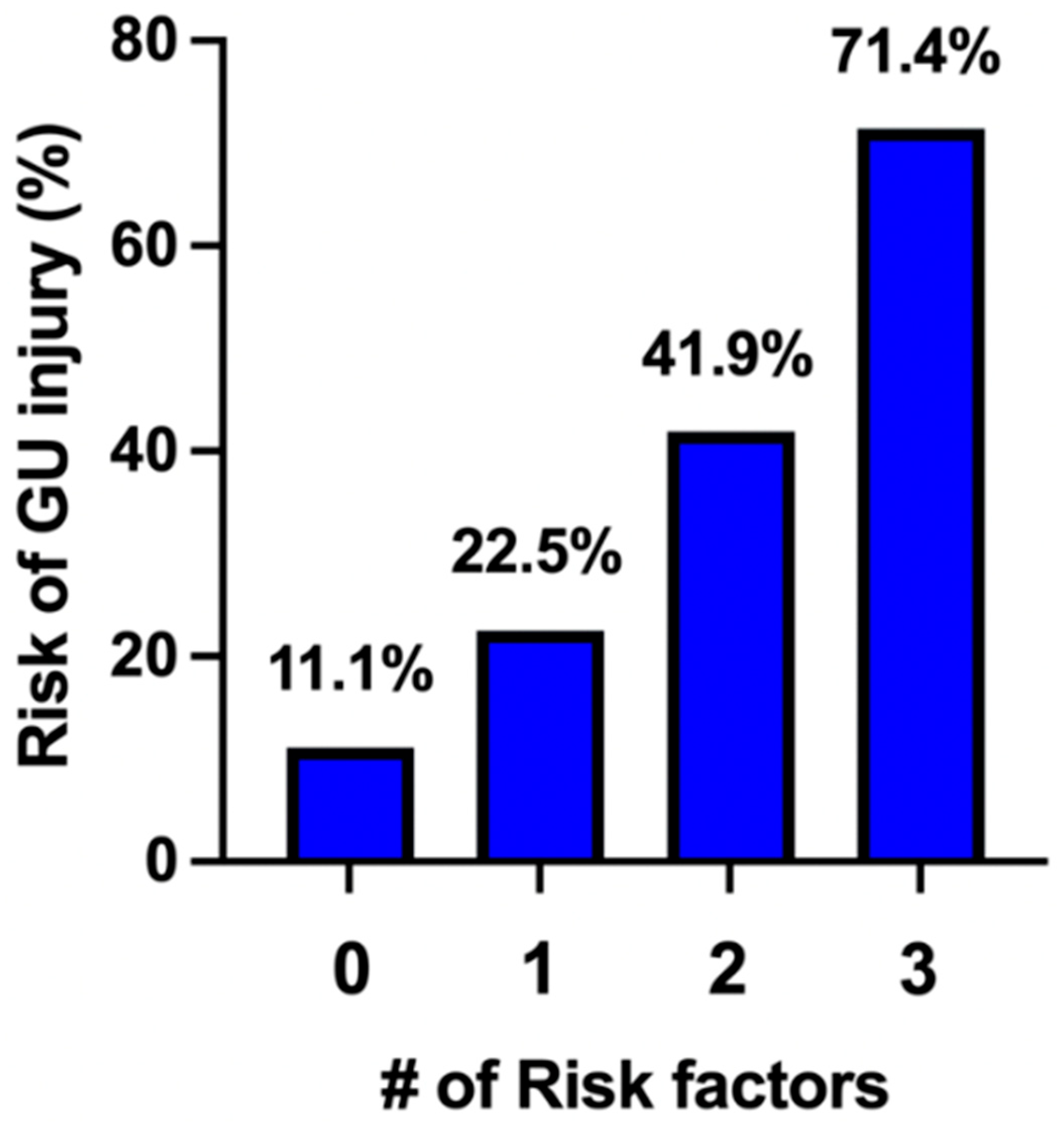

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Einerson, B.D.; Comstock, J.; Silver, R.M.; Branch, D.W.; Woodward, P.J.; Kennedy, A. Placenta accreta spectrum disorder: Uterine dehiscence, not placental invasion. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, R.M.; Barbour, K.D. Placenta accreta spectrum: Accreta, increta, and percreta. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 42, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Kocherginsky, M.; Hibbard, J.U. Abnormal placentation: Twenty-year analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 192, 1458–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, R.M.; Branch, D.W. Placenta accreta spectrum. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, K.B.T.; Dozier, J.; Martin, J.N., Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: A systematic review. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Antonio, F.; Iacovella, C.; Bhide, A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 42, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, G.D.; Newton, J.; Atasi, L.; Buniak, C.M.; Burgos-Luna, J.M.; Burnett, B.A.; Carver, A.R.; Cheng, C.; Conyers, S.; Davitt, C.; et al. Placenta accreta spectrum care infrastructure: An evidence-based review of needed resources supporting placenta accreta spectrum care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2024, 6, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, Z.S.; Manuck, T.A.; Eller, A.G.; Simons, M.; Silver, R.M. Risk factors for unscheduled delivery in patients with placenta accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 241.e1–241.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucidi, A.; Jauniaux, E.; Hussein, A.M.; Coutinho, C.M.; Tinari, S.; Khalil, A.; Shamshirsaz, A.; Palacios-Jaraquemada, J.M.; D′ANtonio, F. Urological complications in women undergoing cesarean section for placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 62, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, H.; Salmanian, B.; Fox, K.A.; Coburn, M.; Meshinchiasl, N.; Shamshirsaz, A.A.; Kopkin, R.; Gogia, S.; Patel, K.; Jackson, J.; et al. Urologic morbidity associated with placenta accreta spectrum surgeries: Single-center experience with a multidisciplinary team. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 245.e1–245.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, L.; Mor, N.; Weissmann-Brenner, A.; Kassif, E.; Friedrich, S.N.; Weissbach, T.; Castel, E.; Levin, G.; Meyer, R. Risk factors for bladder injury during placenta accreta spectrum surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 161, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hage, L.; Athiel, Y.; Barrois, M.; Cojocariu, V.; Peyromaure, M.; Goffinet, F.; Duquesne, I. Identifying risk factors for urologic complications in placenta accreta spectrum surgical management. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulhall, J.C.; Ireland, K.E.; Byrne, J.J.; Ramsey, P.S.; McCann, G.A.; Munoz, J.L. Association between antenatal vaginal bleeding and adverse perinatal outcomes in placenta accreta spectrum. Medicina 2024, 60, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglione, M.A.; Allshouse, A.A.; Canfield, D.R.; Mclaughlin, H.D.; Bruno, A.M.; Hammad, I.A.; Branch, D.W.; Maurer, K.A.; Dood, R.L.; Debbink, M.P.; et al. Prophylactic ureteral stent placement and urinary injury during hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 140, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, R.; Hessami, K.; Diab, Y.H.; Scaglione, M.; D′ANtonio, F.; Kanaan, C.; Erfani, H.; Abuhamad, A.; Shamshirsaz, A.A. Prophylactic ureteral stent placement for the prevention of genitourinary tract injury during hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentilhes, L.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Seco, A.; Kayem, G. 4: Conservative management versus cesarean hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum; the PACCRETA prospective population-based study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerwise, L.C.; Craig, A.M.; Newton, J.; Zhao, S.; Bennett, K.A.; Crispens, M.A. Outcomes following a clinical algorithm allowing for delayed hysterectomy in the management of severe placenta accreta spectrum. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 179.e1–179.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, R.M.; Fox, K.A.; Barton, J.R.; Abuhamad, A.Z.; Simhan, H.; Huls, C.K.; Belfort, M.A.; Wright, J.D. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, H.; Fox, K.A.; Clark, S.L.; Rac, M.; Hui, S.-K.R.; Rezaei, A.; Aalipour, S.; Shamshirsaz, A.A.; Nassr, A.A.; Salmanian, B.; et al. Maternal outcomes in unexpected placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Single-center experience with a multidisciplinary team. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 337.e1–337.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | No GU Injury (n = 107) | GU Injury (n = 39) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.2 ± 5.5 | 31.5 ± 5.2 | 0.79 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.1 ± 6.2 | 31.7 ± 5.7 | 0.22 |

| Gravidity | 4 [3, 6] | 5 [4, 6] | 0.19 |

| Parity | 3 [2, 3] | 3 [2, 4] | 0.02 |

| History of C/S | 96 (90) | 39 (100) | 0.04 |

| Number of prior C/S | 2 [1, 3] | 3 [2, 4] | 0.01 |

| Tertiary referral | 80 (74.8) | 29 (74.4) | 1.0 |

| EGA at delivery | 34 [33, 36] | 34 [32, 35] | 0.20 |

| Placental location | |||

| Anterior | 79 (73.8) | 35 (89.7) | 0.04 |

| Posterior | 22 (18.7) | 2 (5.1) | 0.02 |

| Lateral | 6 (5.6) | 2 (5.1) | 1.0 |

| PAS by Ultrasound | |||

| Previa | 29 (27.1) | 9 (23.1) | 0.68 |

| Accreta | 57 (53.2) | 15 (38.5) | 0.13 |

| Increta | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2.6) | 1.0 |

| Percreta | 19 (17.8) | 14 (35.9) | 0.03 |

| Pregestational diabetes | 8 (7.5) | 3 (7.7) | 1.0 |

| Chronic Hypertension | 12 (11.2) | 2 (5.1) | 0.35 |

| Emergent delivery | 29 (27.1) | 15 (38.5) | 0.22 |

| Public Insurance | 83 (77.7) | 29 (74.4) | 0.66 |

| Complication | No GU Injury (n = 107) | GU Injury (n = 39) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antepartum admission | 75 (70.1) | 24 (61.5) | 0.32 |

| Antepartum LOS | 1 [0, 3] | 2 [0, 11] | 0.70 |

| PPROM | 5 (4.7) | 2 (5.1) | 1.0 |

| No. Vaginal bleeding | |||

| X1 | 21 (19.6) | 4 (10.3) | 0.22 |

| X2 | 16 (14.9) | 4 (10.3) | 0.59 |

| >2 | 8 (7.5) | 10 (25.6) | 0.008 |

| Preterm Labor | 6 (5.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.68 |

| Gestational HTN | 4 (3.7) | 2 (5.1) | 0.66 |

| PreE without SF | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| PreE with SF | 4 (3.7) | 1 (2.6) | 1.0 |

| FGR | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2.6) | 1.0 |

| Gestational DM | 17 (15.9) | 8 (20.1) | 0.62 |

| Anemia | 38 (35.5) | 16 (41) | 0.57 |

| Factor | No GU Injury | GU Injury | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission Hgb | 10.96 ± 1.3 | 10.57 ± 1.5 | 0.23 |

| EBL (mL) | 2500 [1800, 4000] | 4000 [2500, 7500] | <0.0001 |

| Operative Time (m) | 185 [135, 274] | 264 [184, 433] | 0.0006 |

| UAE | 17 (15.9) | 10 (25.6) | 0.23 |

| Ureteral Stent Placement | 50 (46.7) | 19 (48.7) | 0.85 |

| GU Inury | |||

| Intention Cystotomy | - | 11 (28.2) | |

| Incidental Cystotomy | - | 29 (74.4) | |

| Ureteral | - | 5 (12.8) | |

| ICU Admission | 38 (35.5) | 26 (66.7) | 0.001 |

| ICU LOS | 0 [0, 1] | 1 [0, 2] | 0.0003 |

| Post Op LOS | 3 [3, 5] | 4 [3, 6] | 0.01 |

| Pathology | |||

| Accreta | 25 (23.4) | 5 (12.8) | 0.24 |

| Increta | 33 (30.8) | 8 (20.5) | 0.29 |

| Percreta | 49 (45.8) | 26 (66.7) | 0.04 |

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | aOR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior placentation | 4.01 | [1.92, 4.67] | 0.03 | 3.73 | [1.2, 16.7] | 0.04 |

| Percreta by ultrasound | 2.89 | [1.22, 6.56] | 0.01 | 1.95 | [1.1, 6.2] | 0.03 |

| Vaginal bleeding > 2 | 4.27 | [1.55, 12.16] | 0.005 | 4.11 | [1.4, 12.6] | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mulhall, J.C.; Ireland, K.E.; Byrne, J.J.; Ramsey, P.S.; McCann, G.A.; Munoz, J.L. Risk Factors and Clinical Significance of Urologic Injury in Cesarean Hysterectomy for Placenta Accreta Spectrum. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207199

Mulhall JC, Ireland KE, Byrne JJ, Ramsey PS, McCann GA, Munoz JL. Risk Factors and Clinical Significance of Urologic Injury in Cesarean Hysterectomy for Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207199

Chicago/Turabian StyleMulhall, J. Connor, Kayla E. Ireland, John J. Byrne, Patrick S. Ramsey, Georgia A. McCann, and Jessian L. Munoz. 2025. "Risk Factors and Clinical Significance of Urologic Injury in Cesarean Hysterectomy for Placenta Accreta Spectrum" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207199

APA StyleMulhall, J. C., Ireland, K. E., Byrne, J. J., Ramsey, P. S., McCann, G. A., & Munoz, J. L. (2025). Risk Factors and Clinical Significance of Urologic Injury in Cesarean Hysterectomy for Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207199