Latent Structure and Profiles of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression Patterns with the Polish Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Process Model of Emotion Regulation

1.2. Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression and Their Links to Mental Health

1.3. Latent Structure of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)

1.4. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) in the Polish Context

1.5. Profiles of Emotion Regulation and Mental Health Outcomes

1.6. The Present Paper

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. The Demographic Questionnaire

2.3.2. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) and Its Translation

2.3.3. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4)

2.3.4. The WHO-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5)

2.3.5. The Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire-Short Form (PAQ-S)

2.4. Analytic Strategy

2.4.1. Factor Structure

2.4.2. Measurement Invariance

2.4.3. Relationships with Positive and Negative Mental Health Outcomes

2.4.4. Demographic Differences

2.4.5. Latent Profile Analysis

2.4.6. Profile Comparisons

2.4.7. Group Norms

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Internal Consistency Reliability Coefficients

3.2. Factor Structure

3.3. Measurement Invariance

3.4. Relationships with Positive and Negative Mental Health Outcomes

3.5. Demographic Differences

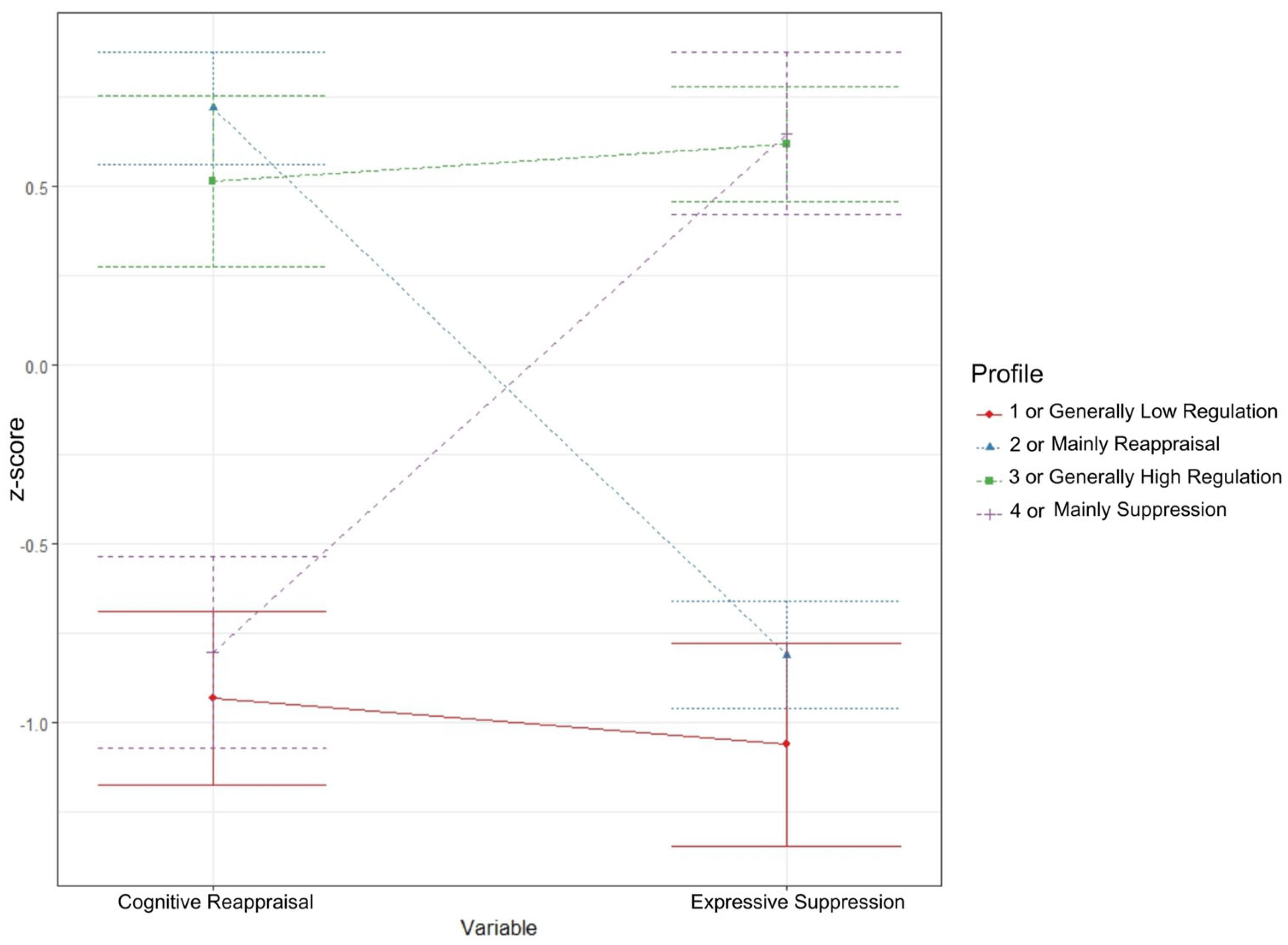

3.6. Latent Profile Analysis

3.7. Profile Comparisons

3.8. Group Norms

4. Discussion

4.1. Latent Structure

4.2. Internal Consistency Reliability

4.3. Measurement Invariance

4.4. Demographic Differences

4.5. Relationships with Positive and Negative Mental Health Outcomes

4.6. Latent Profiles of Emotion Regulation

4.7. Future Directions

4.8. Practical Implications of the Study and the Use of Polish Norms

4.9. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Profiles | AIC | BIC | CLC | KIC | AWE | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3008.47 | 3025.56 | 3002.47 | 3015.47 | 3060.64 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2995.96 | 3025.86 | 2982.98 | 3005.96 | 3089.74 | 0.51 |

| 1 | 3 | 2990.55 | 3033.26 | 2971.38 | 3003.55 | 3125.14 | 0.41 |

| 1 | 4 | 2975.29 | 3030.81 | 2950.43 | 2991.29 | 3150.2 | 0.57 |

| 1 | 5 | 2972.55 | 3040.88 | 2941.77 | 2991.55 | 3188 | 0.61 |

| 1 | 6 | 2973.82 | 3054.97 | 2937.01 | 2995.82 | 3229.93 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 7 | 2980.47 | 3074.43 | 2937.58 | 3005.47 | 3277.29 | 0.56 |

| 1 | 8 | 2985.93 | 3092.7 | 2937.02 | 3013.93 | 3323.39 | 0.54 |

References

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Weiss, N.H.; Tull, M.T. Examining emotion regulation as an outcome, mechanism, or target of psychological treatments. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 3, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, L.; Ebner, C.; Leo, K.; Lindenberg, K. Emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression, anxiety, aggression, and addiction in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2023, 30, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menefee, D.S.; Ledoux, T.; Johnston, C.A. The importance of emotional regulation in mental health. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 16, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellern, J.; Xiao, K.B.; Grennell, E.; Sanches, M.; Gowin, J.L.; Sloan, M.E. Emotion regulation in substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2023, 118, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.; Hall, K.; Moulding, R.; Bryce, S.; Mildred, H.; Staiger, P.K. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, F.E.; Vergara-Barra, P.; Concha-Ponce, P.; Andrades, M.; Rincón, P.; Valdivia-Devia, M. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and prediction of posttraumatic consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chilean adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preece, D.A.; Becerra, R.; Robinson, K.; Gross, J.J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric properties in general community samples. J. Pers. Assess. 2020, 102, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preece, D.A.; Petrova, K.; Mehta, A.; Gross, J.J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Short Form (ERQ-S): A 6-item measure of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzarotti, S.; John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. An Italian adaptation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.; Kneebone, I.I.; Bailey, P.E. Validation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in older community-dwelling adults. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 58, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, R.; Salguero, J.M.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Gross, J.J. A Spanish adaptation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 29, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.N.; Yeung, D.Y.; Gerstein, L.H.; Wettersten, K.B. Psychometric comparison of Chinese and English versions of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire with bilingual Hong Kong Chinese students. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.L.C.B.; Pasian, S.R.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F. Gender invariance and psychometric properties of a Brazilian version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 43, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Becerra, R.; Hasking, P.; McEvoy, P.M.; Boyes, M.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Chen, W.; Gross, J.J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and relations with affective symptoms in a United States general community sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 284, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörman, K.; Garke, M.Å.; Isacsson, N.H.; Jangard, S.; Bjureberg, J.; Hellner, C.; Sinha, R.; Jayaram-Lindström, N. Measures of emotion regulation: Convergence and psychometric properties of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale and emotion regulation questionnaire. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Preece, D.A. The Polish Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Short Form (ERQ-S): Psychometric Properties, Polish Norms and Relationships with Psychopathology and Well-Being. Camb. Prism. Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, D.; Zajenkowski, M.; Lewczuk, K.; Jankowski, K.S.; Marchlewska, M. The mediational role of emotion regulation in the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 4098–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmieja, M.; Mrozowicz, M.; Kobylińska, D. Emotional intelligence and emotion regulation strategies. Stud. Psychol. 2011, 49, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, K.; Warren, P.; Flory, K. A Variable-Centered and Person-Centered Evaluation of Emotion Regulation and Distress Tolerance: Links to Emotional and Behavioral Concerns. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guérin-Marion, C.; Bureau, J.-F.; Lafontaine, M.-F.; Gaudreau, P.; Martin, J. Profiles of Emotion Dysregulation Among University Students Who Self-Injure: Associations with Parent–Child Relationships and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Characteristics. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.L.C.B.; Pasian, S.R.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F. Identifying and validating emotion regulation latent profiles and their relationship with affective variables. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J. Emotion regulation in undergraduate nursing students: A latent profile analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023, 71, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesney, S.A.; Timmer-Murillo, S.C.; Gordon, N.S. Establishment and Replication of Emotion Regulation Profiles: Implications for Psychological Health. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, A.; Zoellner, L.A.; Vigil, S.A. Patterns of emotion regulation and psychopathology. Anxiety Stress Coping 2009, 22, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S. Psychiatric Symptoms and Emotion Regulation Strategies among the Unemployed People in Korea: A Latent Profile Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Long, M.; Shi, J. A Latent Profile Analysis of Emotion Regulation in Relation to Distress of Symptoms in Youth with Prodromal Psychotic Symptoms. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grommisch, G.; Koval, P.; Hinton, J.D.X.; Gleeson, J.; Hollenstein, T.; Kuppens, P.; Lischetzke, T. Modeling Individual Differences in Emotion Regulation Repertoire in Daily Life with Multilevel Latent Profile Analysis. Emotion 2020, 20, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.N.; Yao, S.Q.; Xin, X.H. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies among Chinese Adolescents Having Unprotected Sex: A Latent Profile Analysis. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, C.; Lin, M.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, P. Latent Profiles of Emotion Regulation Strategies Associated with Alexithymia, Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Resilience among Nursing Students. Stress Health 2022, 38, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Heuvel, M.W.H.; Stikkelbroek, Y.A.J.; Bodden, D.H.M.; van Baar, A.L. Coping with stressful life events: Cognitive emotion regulation profiles and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Dev. Psychopathol. 2020, 32, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüning, D.J.; Hangel, N. How to promote more nuanced construct theories: An interdisciplinary perspective with pragmatic recommendations. PsyArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, G.; Suri, G.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawel, A.; Shou, Y.; Gulliver, A.; Cherbuin, N.; Banfield, M.; Murray, K.; Calear, A.L.; Morse, A.R.; Farrer, L.M.; Smithson, M. Cause or symptom? A longitudinal test of bidirectional relationships between emotion regulation strategies and mental health symptoms. Emotion 2021, 21, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.; Becerra, R.; Allan, A.; Robinson, K.; Dandy, J. Establishing the theoretical components of alexithymia via factor analysis: Introduction and validation of the attention-appraisal model of alexithymia. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminet, O.; Nielson, K.A. Alexithymia: Towards an Experimental, Processual Affective Science with Effective Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Wang, M.; Valero, D.; Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larionow, P.; Mudło-Głagolska, K. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4: Factor structure, measurement invariance, latent profile analysis of anxiety and depressive symptoms and screening results in Polish adults. Adv. Cogn. Psychol. 2023, 19, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Wellbeing Measures in Primary Health Care/the DepCare Project: Report on a WHO Meeting: Stockholm, Sweden, 12–13 February 1998. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. 1998. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/349766 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Larionow, P. Anxiety and depression screening among Polish adults in 2023: Depression levels are higher than in cancer patients. Psychiatria 2023, 20, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichoń, E.; Kiejna, A.; Kokoszka, A.; Gondek, T.; Rajba, B.; Lloyd, C.E.; Sartorius, N. Validation of the Polish version of WHO-5 as a screening instrument for depression in adults with Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 159, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preece, D.A.; Mehta, A.; Petrova, K.; Sikka, P.; Bjureberg, J.; Chen, W.; Becerra, R.; Allan, A.; Robinson, K.; Gross, J.J. The Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire-Short Form (PAQ-S): A 6-item measure of alexithymia. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 325, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Preece, D.A.; Mudło-Głagolska, K. The Polish version of the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire-Short Form (PAQ-S): Psychometric properties and norms. J. Sex. Ment. Health 2023, 21, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth-Marnat, G. Handbook of Psychological Assessment, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Definition of Youth. 2013. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, J.; Davidov, E. Establishing measurement invariance across online and offline samples: A tutorial with the software packages Amos and Mplus. Stud. Psychol. Theor. Et Prax. 2015, 15, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.M.; Beymer, P.N.; Anderson, D.J.; van Lissa, C.J.; Schmidt, J.A. tidyLPA: An R Package to Easily Carry Out Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) Using Open-Source or Commercial Software. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akogul, S.; Erisoglu, M. An Approach for Determining the Number of Clusters in a Model-Based Cluster Analysis. Entropy 2017, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tein, J.-Y.; Coxe, S.; Cham, H. Statistical Power to Detect the Correct Number of Classes in Latent Profile Analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2013, 20, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J.R.; Garthwaite, P.H.; Slick, D.J. On Percentile Norms in Neuropsychology: Proposed Reporting Standards and Methods for Quantifying the Uncertainty over the Percentile Ranks of Test Scores. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2009, 23, 1173–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, D.P.; Caltabiano, L.F. Test scores: A guide to understanding and using test results. In Helping Children at Home and School II: Handouts for Families and Educators; Canter, A.S., Paige, L.Z., Roth, M.D., Eds.; National Association of School Psychologists: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, A.M.; Galiano, C.S.; Rosellini, A.J.; Brown, T.A. Psychometric evaluation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in a clinical sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2024, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, T.; Schulz, M.S.; Gross, J.J.; Matos, P.M. The emotion regulation questionnaire in women with cancer: A psychometric evaluation and an item response theory analysis. Psycho-oncology 2017, 26, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghart, M.; Sahm, A.H.J.; Mier, D. Investigating measurement invariance of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-8 (ERQ-8) across 29 countries. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 32054–32060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.X.M.; Preece, D.A.; Weinborn, M.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Becerra, R. Assessing Emotion Regulation across Asian and Western Cultures: Psychometric Properties of Three Common Scales across Singaporean and Australian Samples. J. Pers. Assess. 2023, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doren, N.; Zainal, N.H.; Newman, M.G. Cross-cultural and gender invariance of emotion regulation in the United States and India. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bian, Y. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Cross-Gender Measurement Invariance in Chinese University Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, K.; Taishi, N.; Shiozaki, M. Age and Gender Differences in Relationships Among Emotion Regulation, Mood, and Mental Health. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 2, 2333721416637022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olalde-Mathieu, V.E.; Licea-Haquet, G.; Reyes-Aguilar, A.; Barrios, F.A. Psychometric properties of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in a Mexican sample and their correlation with empathy and alexithymia. Cogent Psychol. 2022, 9, 2053385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gende. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, R.; Pignault, A.; Houssemand, C. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Adapated and Individual Differences in Emotion Regulation. Eur. J. Psychol. 2021, 17, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Gondo, Y.; Ishioka, Y.; Masui, Y. Age, emotion regulation, and affect in adulthood: The mediating role of cognitive reappraisal. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2017, 59, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.; Wang, X. Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis Review. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-X.; Yin, B. A New Understanding of the Cognitive Reappraisal Technique: An Extension Based on the Schema Theory. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1174585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.A.; Tone, E.B. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Expressive Suppression and Positive Affect. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 88, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, A.; Sheppes, G.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation Flexibility. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2015, 39, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olderbak, S.; Uusberg, A.; MacCann, C.; Pollak, K.M.; Gross, J.J. The Process Model of Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Assessing Individual Differences in Strategy Stage and Orientation. Assessment 2023, 30, 2090–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Farchione, T.J.; Bullis, J.R.; Gallagher, M.W.; Murray-Latin, H.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Bentley, K.H.; Thompson-Hollands, J.; Conklin, L.R.; Boswell, J.F.; et al. The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders Compared With Diagnosis-Specific Protocols for Anxiety Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, M.N.; Molina, P.; Abler, B.; Kessler, H.; Vanbrabant, L.; van de Schoot, R. Measurement invariance of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). A cross-national validity study. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 27.46, SD = 11.24, median = 23.00, min. = 18, max. = 75 | 1197 | 100 | |

| People aged 18–24 | M = 20.60, SD = 1.86, median = 20.00, min. = 18, max. = 24 | 720 | 60.15 | |

| People aged 25–75 | M = 37.81, SD = 11.56, median = 35.00, min. = 25, max. = 75 | 477 | 39.85 | |

| Gender | Females | 897 | 74.94 | |

| Males | 276 | 23.06 | ||

| Non-binary individuals | 24 | 2.01 | ||

| Education | University degree | Higher | 410 | 34.25 |

| No university degree (total n = 787) | Secondary | 661 | 55.22 | |

| Vocational | 63 | 5.26 | ||

| Primary | 63 | 5.26 | ||

| Scale/Subscale | Total Sample | Females | Males | Non-Binary | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | ω (95% CI) | α (95% CI) | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| ERQ Cognitive reappraisal | 1197 | 0.86 (0.85; 0.87) | 0.86 (0.84; 0.87) | 25.01 | 8.16 | 897 | 24.64 | 8.15 | 276 | 26.29 | 8.09 | 24 | 24.25 | 8.24 |

| ERQ Expressive suppression | 1197 | 0.79 (0.77; 0.81) | 0.77 (0.75; 0.79) | 16.33 | 5.88 | 897 | 15.84 | 6.01 | 276 | 17.84 | 5.20 | 24 | 17.25 | 5.70 |

| PHQ-4 Anxiety | 529 | 0.78 (0.74; 0.82) | 0.78 (0.74; 0.82) | 3.50 | 1.82 | 441 | 3.59 | 1.78 | 80 | 2.93 | 2.00 | 8 | 4.50 | 1.41 |

| PHQ-4 Depression | 529 | 0.83 (0.80; 0.86) | 0.83 (0.80; 0.86) | 2.95 | 1.95 | 441 | 3.02 | 1.96 | 80 | 2.59 | 1.89 | 8 | 3.25 | 1.83 |

| PHQ-4 Total score | 529 | 0.86 (0.84; 0.88) | 0.86 (0.84; 0.88) | 6.45 | 3.46 | 441 | 6.60 | 3.40 | 80 | 5.51 | 3.72 | 8 | 7.75 | 3.01 |

| WHO-5 Total score | 1197 | 0.85 (0.84; 0.86) | 0.85 (0.84; 0.86) | 8.99 | 4.78 | 897 | 8.59 | 4.61 | 276 | 10.50 | 5.08 | 24 | 6.71 | 3.74 |

| PAQ-S Total score | 529 | 0.83 (0.81; 0.85) | 0.83 (0.81; 0.85) | 20.71 | 8.79 | 441 | 20.75 | 8.84 | 80 | 19.99 | 8.54 | 8 | 25.63 | 7.60 |

| ERQ Items | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Factor Loading on Intended Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. “When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about.” | 4.34 | 1.75 | −0.37 | −0.76 | 0.56 | – |

| 2. “I keep my emotions to myself.” | 4.86 | 1.88 | −0.58 | −0.85 | – | 0.75 |

| 3. “When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about.” | 4.13 | 1.86 | −0.14 | −1.06 | 0.63 | – |

| 4. “When I am feeling positive emotions, I am careful not to express them.” | 2.67 | 1.72 | 0.94 | −0.11 | – | 0.46 |

| 5. “When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm.” | 4.42 | 1.91 | −0.35 | −1.02 | 0.59 | – |

| 6. “I control my emotions by not expressing them.” | 4.23 | 2.05 | −0.24 | −1.27 | – | 0.81 |

| 7. “When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.” | 4.17 | 1.72 | −0.23 | −0.83 | 0.79 | – |

| 8. “I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in.” | 3.97 | 1.73 | −0.17 | −0.92 | 0.78 | – |

| 9. “When I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them.” | 4.57 | 1.96 | −0.43 | −1.08 | – | 0.70 |

| 10. “When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.” | 3.99 | 1.72 | −0.16 | −0.93 | 0.86 | – |

| Sample/Model | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR | Invariance Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 1197)/2-factor model | 374.92 (34) | 0.908 | 0.879 | 0.103 (0.094; 0.112) | 0.069 | – | – | – | – |

| Total sample (n = 1197)/2-factor model with a correlated error term between items 1 and 3 | 254.94 (33) | 0.941 | 0.92 | 0.084 (0.074; 0.093) | 0.063 | – | – | – | – |

| Invariance models (for the final 2-factor model with an error term between items 1 and 3) | |||||||||

| Gender invariance (females [n = 897] vs. males [n = 276]) | |||||||||

| Configural | 292.56 (66) | 0.939 | 0.916 | 0.085 (0.075; 0.095) | 0.059 | – | – | – | – |

| Metric | 303.75 (74) | 0.939 | 0.926 | 0.080 (0.071; 0.090) | 0.06 | 0 | −0.005 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Scalar | 319.16 (82) | 0.938 | 0.932 | 0.077 (0.068; 0.085) | 0.061 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Age invariance (aged 18–24 [n = 720] vs. aged 25–75 [n = 477]) | |||||||||

| Configural | 295.04 (66) | 0.939 | 0.917 | 0.085 (0.075; 0.095) | 0.06 | – | – | – | – |

| Metric | 310.24 (74) | 0.939 | 0.925 | 0.081 (0.072; 0.090) | 0.062 | 0 | −0.004 | 0.002 | Supported |

| Scalar | 332.55 (82) | 0.936 | 0.93 | 0.078 (0.069; 0.087) | 0.063 | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Education invariance (no university degree [n = 787] vs. university degree [n = 410]) | |||||||||

| Configural | 297.86 (66) | 0.939 | 0.917 | 0.085 (0.075; 0.095) | 0.061 | – | – | – | – |

| Metric | 313.42 (74) | 0.939 | 0.925 | 0.081 (0.072; 0.090) | 0.063 | 0 | −0.004 | 0.002 | Supported |

| Scalar | 334.27 (82) | 0.937 | 0.93 | 0.078 (0.069; 0.087) | 0.064 | −0.002 | −0.003 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Psychopathology symptom invariance (PHQ-4 Total scores of 0–5 [n = 234] vs. PHQ-4 Total scores of 6–12 [n = 295]) | |||||||||

| Configural | 156.44 (66) | 0.947 | 0.928 | 0.079 (0.063; 0.095) | 0.059 | – | – | – | – |

| Metric | 163.68 (74) | 0.948 | 0.937 | 0.073 (0.058; 0.089) | 0.062 | 0.001 | −0.006 | 0.003 | Supported |

| Scalar | 194.59 (82) | 0.936 | 0.93 | 0.077 (0.063; 0.091) | 0.068 | −0.012 | 0.004 | 0.006 | Supported |

| Alexithymia level invariance (PAQ-S Total scores of 6–26 [n = 391] vs. PAQ-S Total scores of 27–42 [n = 138]) | |||||||||

| Configural | 156.58 (66) | 0.944 | 0.923 | 0.080 (0.064; 0.096) | 0.06 | – | – | – | – |

| Metric | 167.60 (74) | 0.942 | 0.929 | 0.077 (0.061; 0.092) | 0.066 | −0.002 | −0.003 | 0.006 | Supported |

| Scalar | 199.76 (82) | 0.929 | 0.922 | 0.081 (0.066; 0.095) | 0.072 | −0.013 | 0.004 | 0.006 | Supported |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ERQ Cognitive reappraisal (n = 1197) | — | ||||||

| 2. ERQ Expressive suppression (n = 1197) | −0.03 | — | |||||

| 3. PHQ-4 Anxiety (n = 529) | −0.23 *** | 0.18 *** | — | ||||

| 4. PHQ-4 Depression (n = 529) | −0.28 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.69 *** | — | |||

| 5. PHQ-4 Total score (n = 529) | −0.28 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.91 *** | 0.92 *** | — | ||

| 6. WHO-5 Total score (n = 1197) | 0.39 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.65 *** | −0.73 *** | −0.75 *** | — | |

| 7. PAQ-S Total score (n = 529) | −0.21 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.32 *** | −0.35 *** | — |

| Generally Low Regulation or Profile 1 (n = 63) | Mainly Reappraisal or Profile 2 (n = 149) | Generally High Regulation or Profile 3 (n = 160) | Mainly Suppression or Profile 4 (n = 157) | ANOVA Parameters | Significant Differences Between Profiles (Post Hoc Comparisons) | Effect Size (η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile Prevalence (%) | 11.91 | 28.17 | 30.25 | 29.68 | |||

| Profile Description | Low CR with Low ES | High CR with Low ES | High CR with High ES | Low CR with High ES | |||

| Variables | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| 1. ERQ Cognitive reappraisal | 15.92 (4.24) | 31.09 (5.00) | 30.19 (4.62) | 17.37 (4.69) | F(3, 525) = 363.29, p < 0.001 | 1 < 2, 1 < 3, 2 > 4, 3 > 4 | 0.67 |

| 2. ERQ Expressive suppression | 8.75 (2.95) | 10.66 (2.97) | 20.18 (3.16) | 19.58 (3.72) | F(3, 525) = 386.38, p < 0.001 | 1 < 2, 1 < 3, 1 < 4, 2 < 3, 2 < 4 | 0.69 |

| 3. PHQ-4 Anxiety | 3.62 (1.81) | 2.95 (1.81) | 3.51 (1.67) | 3.96 (1.86) | F(3, 525) = 8.36, p < 0.001 | 2 < 3, 2 < 4 | 0.05 |

| 4. PHQ-4 Depression | 2.84 (1.82) | 2.05 (1.80) | 3.13 (1.82) | 3.68 (1.92) | F(3, 525) = 20.66, p < 0.001 | 1 > 2, 1 < 4, 2 < 3, 2 < 4, 3 < 4 | 0.11 |

| 5. PHQ-4 Total score | 6.46 (3.42) | 4.99 (3.33) | 6.64 (3.23) | 7.64 (3.37) | F(3, 525) = 16.49, p < 0.001 | 1 > 2, 2 < 3, 2 < 4, 3 < 4 | 0.09 |

| 6. WHO-5 Total score | 8.79 (4.81) | 11.36 (4.81) | 8.90 (4.50) | 7.11 (4.23) | F(3, 525) = 22.42, p < 0.001 | 1 < 2, 2 > 3, 2 > 4, 3 > 4 | 0.11 |

| 7. PAQ-S Total score | 17.65 (8.45) | 15.05 (6.73) | 23.82 (7.66) | 24.14 (8.61) | F(3, 525) = 47.94, p < 0.001 | 1 < 3, 1 < 4, 2 < 3, 2 < 4 | 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larionow, P.; Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Preece, D.A. Latent Structure and Profiles of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression Patterns with the Polish Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020587

Larionow P, Mudło-Głagolska K, Preece DA. Latent Structure and Profiles of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression Patterns with the Polish Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020587

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarionow, Paweł, Karolina Mudło-Głagolska, and David A. Preece. 2025. "Latent Structure and Profiles of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression Patterns with the Polish Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020587

APA StyleLarionow, P., Mudło-Głagolska, K., & Preece, D. A. (2025). Latent Structure and Profiles of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression Patterns with the Polish Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020587