Cardiovascular Anesthesia and Critical Care in the French West Indies: Historical Evolution and Current Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgeries

1.2. Cardiothoracic Anaesthesia

2. Characteristics of the Population

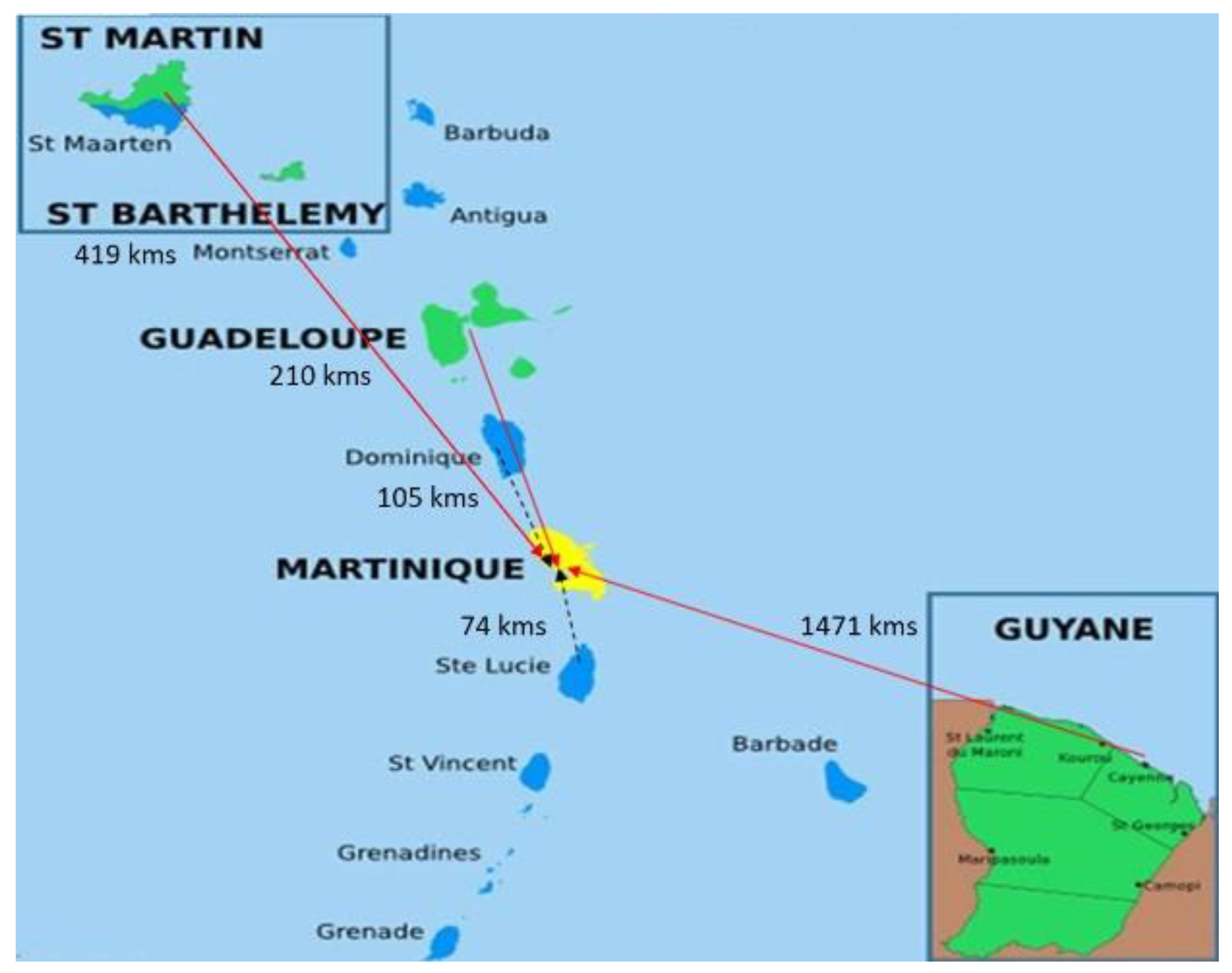

2.1. Socio-Geographical Aspects

2.2. Health Issues in Caribbean Countries

2.2.1. Life Expectancy and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

2.2.2. Infections and Rheumatic Heart Disease

2.2.3. Specific Non-Communicable Diseases

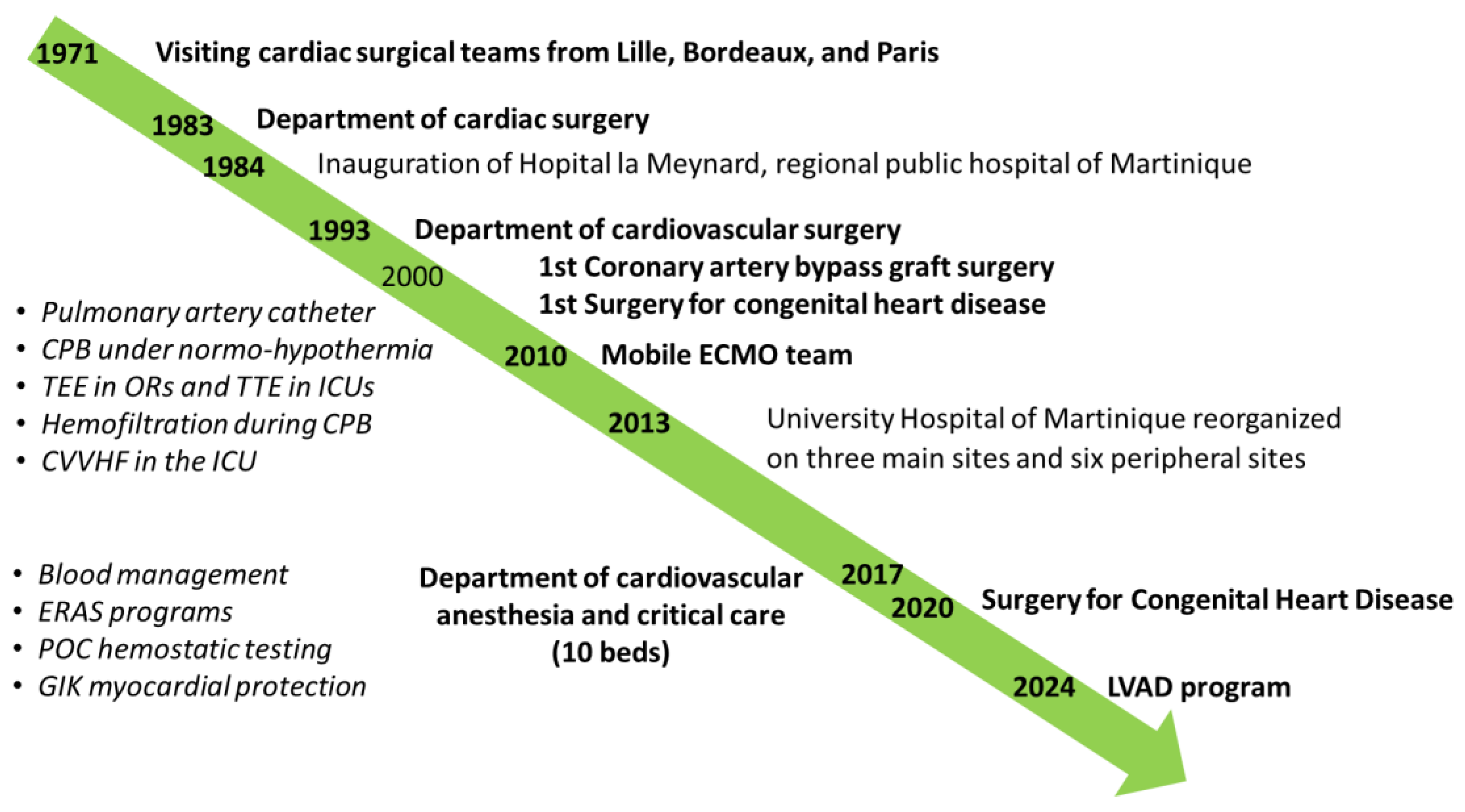

3. Development of Cardiac Surgery, Anesthesia, and Critical Care in Martinique

3.1. Centralization of Medical Care, from a General Hospital to an Academic Center

3.2. Cardiac Surgery in Fort de France

3.3. ECMO Team in French West Indies

Cardiovascular and Thoracic Anesthesia and Critical Care

4. Cardiac Surgical Program in Caribbean Territories

4.1. Current Situation

4.2. Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robinson, D.H.; Toledo, A.H. Historical Development of Modern Anesthesia. J. Investig. Surg. 2012, 25, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopanczyk, R.; Kumar, N.; Bhatt, A.M. A Brief History of Cardiothoracic Surgical Critical Care Medicine in the United States. Medicina 2022, 58, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.K.; Hollman, A. History of Cardiac Surgery. Heart 2002, 87, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaitan, P.G.; D’Amico, T.A. Milestones in Thoracic Surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 2779–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.W. The History of Extracorporeal Oxygenators. Anaesthesia 2006, 61, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontan, F.; Moghissi, K.; Borst, H.; Turina, M. 25th Anniversary of the Foundation of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011, 40, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinck, E.E.; Ebels, T.; Hittinger, R.; Peterson, T.F. Cardiothoracic Surgery in the Caribbean. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 36, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.; Charlesworth, M.; Pratt, O.; Sutton, R.; Metodiev, Y. Anaesthetic Subspecialties and Sustainable Healthcare: A Narrative Review. Anaesthesia 2024, 79, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F.E.; Fong, K.; Hirsch, N.; Nolan, J.P. Intensive Care Medicine Is 60 Years Old: The History and Future of the Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Med. 2014, 14, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.C.; Hicks, M.H.; Jabaley, C.S.; Simmons, S.; Maxey-Jones, C.; Moitra, V.; Brown, D.; Khanna, A.K.; Kidd, B.; Chow, J.; et al. Sustainability of the Subspecialty of Anesthesiology Critical Care: An Expert Consensus and Review of the Literature. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2024, 38, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tahan, M.R.; Vasquez Le, M.; Alston, R.P.; Erdoes, G.; Schreiber, J.U.; Fassl, J.; Wilkinson, K.; Von Dossow, V.; Greenhalgh, D.; Plamondon, M.J.; et al. Perspectives on the Fellowship Training in Cardiac, Thoracic, and Vascular Anesthesia and Critical Care in Europe From Program Directors and Educational Leads Around Europe. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 34, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, F. Population and Development in the Caribbean (2018–2023): Accelerating Implementation of the Montevideo Consensus; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC): Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United States. Department of State. Bureau of Public Affairs. French Antilles and Guiana. Backgr. Notes Ser. 1983, 1–7. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12178088/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Olié, V.; Gabet, A.; Grave, C.; Gautier, A.; Blacher, J. Prevalence of hypertension in french overseas territories: The santé publique france health barometer survey, 2021. Bull Épidémiol Hebd 2023, 8, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Global Public Health Agenda: An International Consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneuville, M.; Pierrot, J.M.; N’Guyen, R. Particularities of Peripheral Arterial Disease Managed in Vascular Surgery in the French West Indies. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 101, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet Deverly, A.; Amara, M.; Larifla, L.; Velayoudom-Céphise, F.L.; Roques, F.; Kangambega, P.; Hue, K.; Foucan, L. Silent Myocardial Ischaemia and Risk Factors in a Diabetic Afro-Caribbean Population. Diabetes Metab. 2011, 37, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.S. The Importance of Understanding Social and Cultural Norms in Delivering Quality Health Care—A Personal Experience Commentary. TropicalMed 2020, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahall, M. Cardiovascular Disease in the Caribbean: Risk Factor Trends, Care and Outcomes Still Far From Expectations. Cureus 2024, 16, e52581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J.; Bottazzi, M.E.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Ault, S.K.; Periago, M.R. The Neglected Tropical Diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: A Review of Disease Burden and Distribution and a Roadmap for Control and Elimination. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008, 2, e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santé Publique France. Surveillance du VIH et des IST Bactériennes en France en 2023. Available online: https://ors-promotionsante-pdl.centredoc.fr/index.php?lvl=bulletin_display&id=6148 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Ghamari, S.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Saeedi Moghaddam, S.; Aminorroaya, A.; Rezaei, N.; Shobeiri, P.; Esfahani, Z.; Malekpour, M.; Rezaei, N.; Ghanbari, A.; et al. Rheumatic Heart Disease Is a Neglected Disease Relative to Its Burden Worldwide: Findings From Global Burden of Disease 2019. JAHA 2022, 11, e025284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Huang, X.; Qin, J.-J.; Lin, L.; Lei, F.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Sun, T.; Cai, J.; et al. The Projections of Global and Regional Rheumatic Heart Disease Burden from 2020 to 2030. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 941917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, D.; Shen, L.; An, G.; Zhao, S. Global Magnitude and Temporal Trend of Infective Endocarditis, 1990–2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, P.; Kofteridis, D. Special Issue: “Current Trends and Outcomes of Infective Endocarditis”. JCM 2023, 12, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, E.; Olive, C.; Inamo, J.; Roques, F.; Cabié, A.; Hochedez, P. Infective Endocarditis in French West Indies: A 13-Year Observational Study. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Bonilla, G.; Njoroge, J.N.; Pearson, K.; Witteles, R.M.; Aras, M.A.; Alexander, K.M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Curr. Cardiovasc. Risk Rep. 2021, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungu, J.N.; Anderson, L.J.; Whelan, C.J.; Hawkins, P.N. Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Heart 2012, 98, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.M.; McHugh, T.A.; Oron, A.P.; Teply, C.; Lonberg, N.; Vilchis Tella, V.; Wilner, L.B.; Fuller, K.; Hagins, H.; Aboagye, R.G.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence and Mortality Burden of Sickle Cell Disease, 2000–2021: A Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e585–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, V.; Rosing, D.R.; Thein, S.L. Cardiovascular Complications of Sickle Cell Disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 31, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, F.; Pugh, N.; Brambilla, D.; Kroner, B.; Shah, N.; Treadwell, M.; Gibson, R.; Hsu, L.L.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Glassberg, J.; et al. Mortality in Adults with Sickle Cell Disease: Results from the Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC) Registry. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varelas, C.; Gavriilaki, E. Sickle Cell Disease: Current Understanding and Future Options. JCM 2023, 12, 5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; Halas, R.; Kobayashi, D.; Walters, H.L.; Bondarenko, I.; Thomas, R.; Vener, D.F.; Aggarwal, S.; Safa, R. Outcomes of Patients With Sickle Cell Disease and Trait After Congenital Heart Disease Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 115, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, T.C.; Carter, M.V.; Patel, R.K.; Suarez-Pierre, A.; Lin, S.Z.; Magruder, J.T.; Grimm, J.C.; Cameron, D.E.; Baumgartner, W.A.; Mandal, K. Management of Sickle Cell Disease in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. J. Card. Surg. 2017, 32, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oteng-Ntim, E.; Pavord, S.; Howard, R.; Robinson, S.; Oakley, L.; Mackillop, L.; Pancham, S.; Howard, J.; The British Society for Haematology Guidelines Committee. Management of Sickle Cell Disease in Pregnancy. A British Society for Haematology Guideline. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 194, 980–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roques, F. Risk Factors and Outcome in European Cardiac Surgery: Analysis of the EuroSCORE Multinational Database of 19030 Patients. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 1999, 15, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, G.; Sanchez, B.; Hennequin, J.-L.; Resiere, D.; Hommel, D.; Leonard, C.; Mehdaoui, H.; Roques, F. The French Airbridge for Circulatory Support in the Carribean. Interact. CardioVascular Thorac. Surg. 2012, 15, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, G.; Sanchez, B.; Isetta, C.; Hennequin, J.-L.; Mnif, M.-A.; Pécout, F.; Villain-Coquet, L.; Clerel, M.; Combes, A.; Leprince, P.; et al. Transportation of Patients under Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support on an Airliner: Flying Bridge to Transplantation. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 116, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, T.J.; Lipnick, M.S.; Morriss, W.; Gelb, A.W.; Mellin-Olsen, J.; Filipescu, D.; Rowles, J.; Rod, P.; Khan, F.; Yazbeck, P.; et al. The Global Anesthesia Workforce Survey: Updates and Trends in the Anesthesia Workforce. Anesth. Analg. 2024, 139, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, R.H.; Shaw, A.D.; Bartels, K.; Brown, C.H.; Grocott, H.; Heringlake, M.; Gan, T.J.; Miller, T.E.; McEvoy, M.D. The Perioperative Quality Initiative (POQI) 6 Workgroup American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on the Role of Neuromonitoring in Perioperative Outcomes: Cerebral Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrone, M.; Cotter, S.; Swaminathan, M.; McCartney, S. Intraoperative Echocardiography: Guide to Decision-Making. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licker, M.; El Manser, D.; Bonnardel, E.; Massias, S.; Soualhi, I.M.; Saint-Leger, C.; Koeltz, A. Multi-Modal Prehabilitation in Thoracic Surgery: From Basic Concepts to Practical Modalities. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, F.; Futier, E.; Desebbe, O.; Biais, M.; Guinot, P.G.; Leone, M.; Licker, M.J.; Molliex, S.; Pirracchio, R.; Provenchère, S.; et al. Pulse Contour Techniques for Perioperative Hemodynamic Monitoring: A Nationwide Carbon Footprint and Cost Estimation. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2023, 42, 101239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerman, A.; Schorer, R.; Putzu, A.; Keli-Barcelos, G.; Licker, M. Cardioprotective Effects of Glucose-Insulin-Potassium Infusion in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 36, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agati, S.; Bellanti, E. Global Cardiac Surgery—Accessibility to Cardiac Surgery in Developing Countries: Objectives, Challenges, and Solutions. Children 2023, 10, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallel, H.; Resiere, D.; Houcke, S.; Hommel, D.; Pujo, J.M.; Martino, F.; Carles, M.; Mehdaoui, H. Critical Care Medicine in the French Territories in the Americas: Current Situation and Prospects. Rev. Panam. De Salud Pública 2021, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán Milián, M.; Delgado Bereijo, L.; González Jiménez, N. Morbimortality in Heart and Lung Transplantation in Cuba: A 20-Year Follow-Up. Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 3507–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, G.D.; Ramsingh, R.A.E.; Rahaman, N.C.; Rampersad, R.D.; Rampersad, A.; Rampersad, K.A.; Teodori, G. Developing a Cardiac Surgery Unit in the Caribbean: A Reflection. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 3017–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.J.; Grullón-Rodríguez, H.M.; López-Bencosme, Y.; Gresse, S.; Feng, Y.C.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, A. Partial-Cost Analysis and Economic Impact of Ambulatory Coronary Angioplasty in a Private Hospital in the Caribbean. Value Health Reg. Issues 2024, 42, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.-A.; Stephenson, S.; Reid, M.T.; Anderson, S.G. Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiopulmonary Bypass in Jamaica. JTCVS Open 2022, 11, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, D.; Vinck, E.E.; Tiwari, K.K.; Tapaua, N. Cardiac Surgery and Small Island States: A Bridge Too Far? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 111, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, H.A.; Rath, T.E. Cardiac Surgery in Developing Countries. J. Extra Corpor. Technol. 2017, 49, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolman, R.M.; Zilla, P.; Beyersdorf, F.; Boateng, P.; Bavaria, J.; Dearani, J.; Pomar, J.; Kumar, S.; Chotivatanapong, T.; Sliwa, K.; et al. Making a Difference: 5 Years of Cardiac Surgery Intersociety Alliance (CSIA). Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2024, 118, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, K.B.; Moseley, H.S.; Mushlin, P.S.; Hallsworth, R.A.; Fakoory, M.; Walrond, E.R. Anaesthesia in Barbados. Can. J. Anaesth. 1997, 44, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newnham, M.S.; Dan, D.; Maharaj, R.; Plummer, J.M. Surgical Training in the Caribbean: The Past, the Present, and the Future. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1203490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathology | French West Indies and French Guiana | Western Countries (France) |

|---|---|---|

| Obesity | 23% | 16% |

| Arterial hypertension | 23–31% | 20% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12% | 5.7% |

| Sickle cell anemia (homozygous) Sickle cell trait (heterozygous) | 1 in 300 to 600 7–8% | Less than 1 in 5000 2.7% |

| Cardiac amyloidosis | 3–5% | Less than 1.5% |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | 7–39/100,000 | 2.3/100,000 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 6.5/100,000 | 0.9/100,000 |

| Infective endocarditis | 19/100,000 | 17/100,000 |

| Territory—Country | Population, n * | Cardiac Surgery | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start Year | Type of Program | |||

| Bahamas | 415,223 | 1994 | Independent permanent program | |

| Barbados | 281,995 | 1994 | Independent permanent program | |

| Cayman Islands—UK | 90,000 | 2014 | Independent permanent program | |

| Cuba | 11,500,000 | 1968 | Independent permanent programs Cardiac training program | |

| Dominican Republic | 11,465,847 | n.a. | Local and visiting teams | |

| Jamaica | 2,838,235 | 1994 | Local and visiting teams Cardiac training program | |

| Haiti | 11,000,000 | 1996 | Visiting teams and patient transfer abroad | |

| Martinique—F | 366,981 | 1988 | Independent permanent program Cardiac training program | |

| Guadeloupe—F | 395,839 | |||

| French Guiana—F | 312,121 | |||

| Saint Martin—F | 32,077 | |||

| Puerto Rico—USA | 3,260,314 | 1992 | Independent permanent program | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1,535,1019 | 1993 | Independent permanent program | |

| Anguilla—UK | 15,900 |  | Air lifting patients to cardiac surgical centers in Caribbean territories, Colombia, France, Netherlands, United Kingdom, or United States | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 94,298 | |||

| Aruba—NL | 106,277 | |||

| Belize | 410,825 | |||

| Caribbean Netherlands—NL | 27,148 | |||

| Curacao—NL | 192,077 | |||

| Dominica | 73,040 | |||

| Grenada | 126,184 | |||

| Montserrat | 4387 | |||

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 47,755 | |||

| Saint Lucia | 180,251 | |||

| Sint Maarten | 44,222 | |||

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 103,699 | |||

| Turks and Caico Islands—UK | 46,062 | |||

| Virgin Islands—UK | 31,538 | |||

| Virgin Islands—USA | 98,750 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isetta, C.; Barbotin-Larrieu, F.; Massias, S.; El Manser, D.; Koeltz, A.; Balram Christophe, P.S.; Soualhi, M.; Licker, M. Cardiovascular Anesthesia and Critical Care in the French West Indies: Historical Evolution and Current Prospects. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020459

Isetta C, Barbotin-Larrieu F, Massias S, El Manser D, Koeltz A, Balram Christophe PS, Soualhi M, Licker M. Cardiovascular Anesthesia and Critical Care in the French West Indies: Historical Evolution and Current Prospects. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020459

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsetta, Christian, François Barbotin-Larrieu, Sylvain Massias, Diae El Manser, Adrien Koeltz, Patricia Shri Balram Christophe, Mohamed Soualhi, and Marc Licker. 2025. "Cardiovascular Anesthesia and Critical Care in the French West Indies: Historical Evolution and Current Prospects" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020459

APA StyleIsetta, C., Barbotin-Larrieu, F., Massias, S., El Manser, D., Koeltz, A., Balram Christophe, P. S., Soualhi, M., & Licker, M. (2025). Cardiovascular Anesthesia and Critical Care in the French West Indies: Historical Evolution and Current Prospects. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020459