Single-Time Gastroscopy in High-Risk Patients: Screening Effectiveness for Gastric Precancerous Conditions in a Low-To Moderate-Incidence Population

Abstract

- Simple Summary

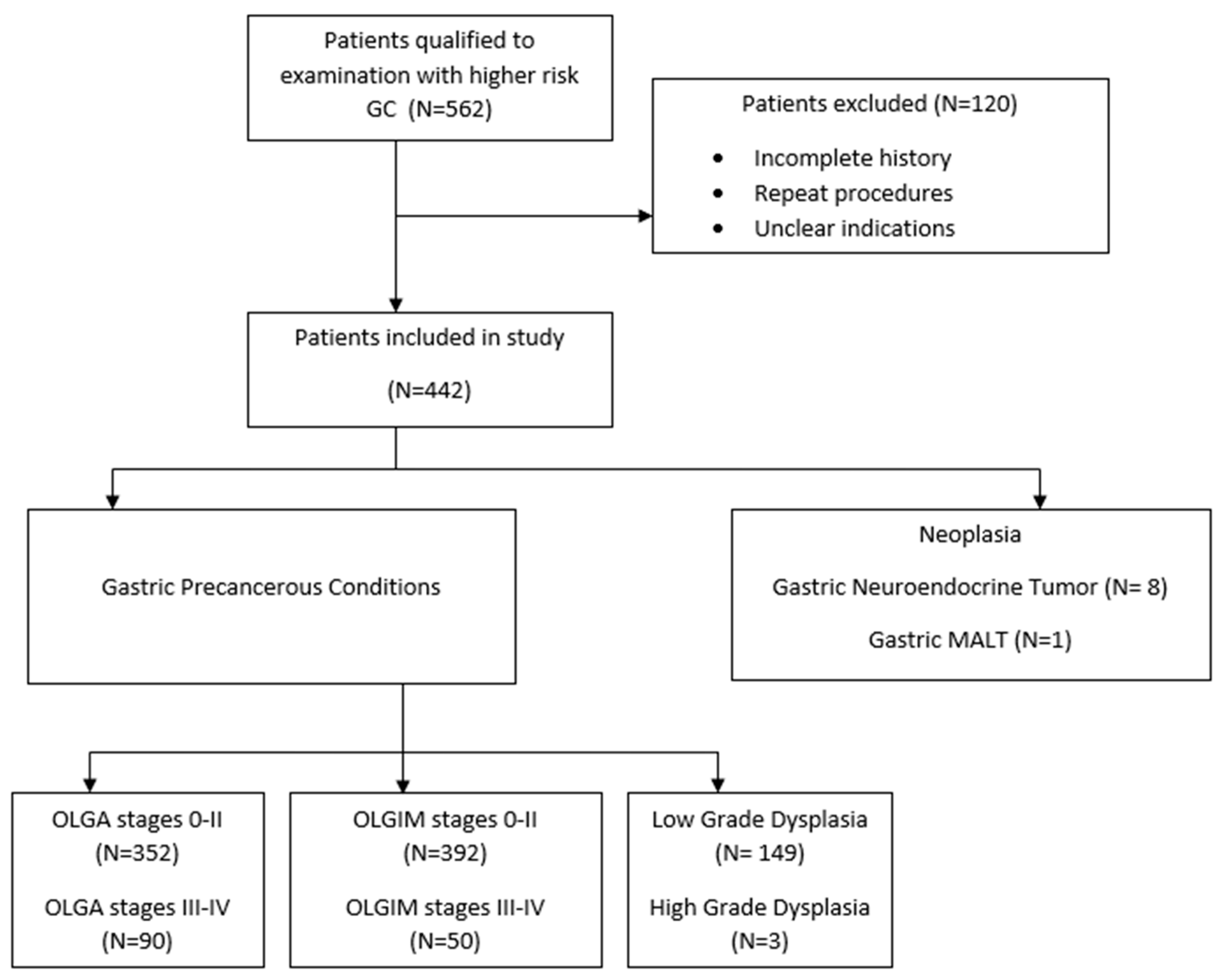

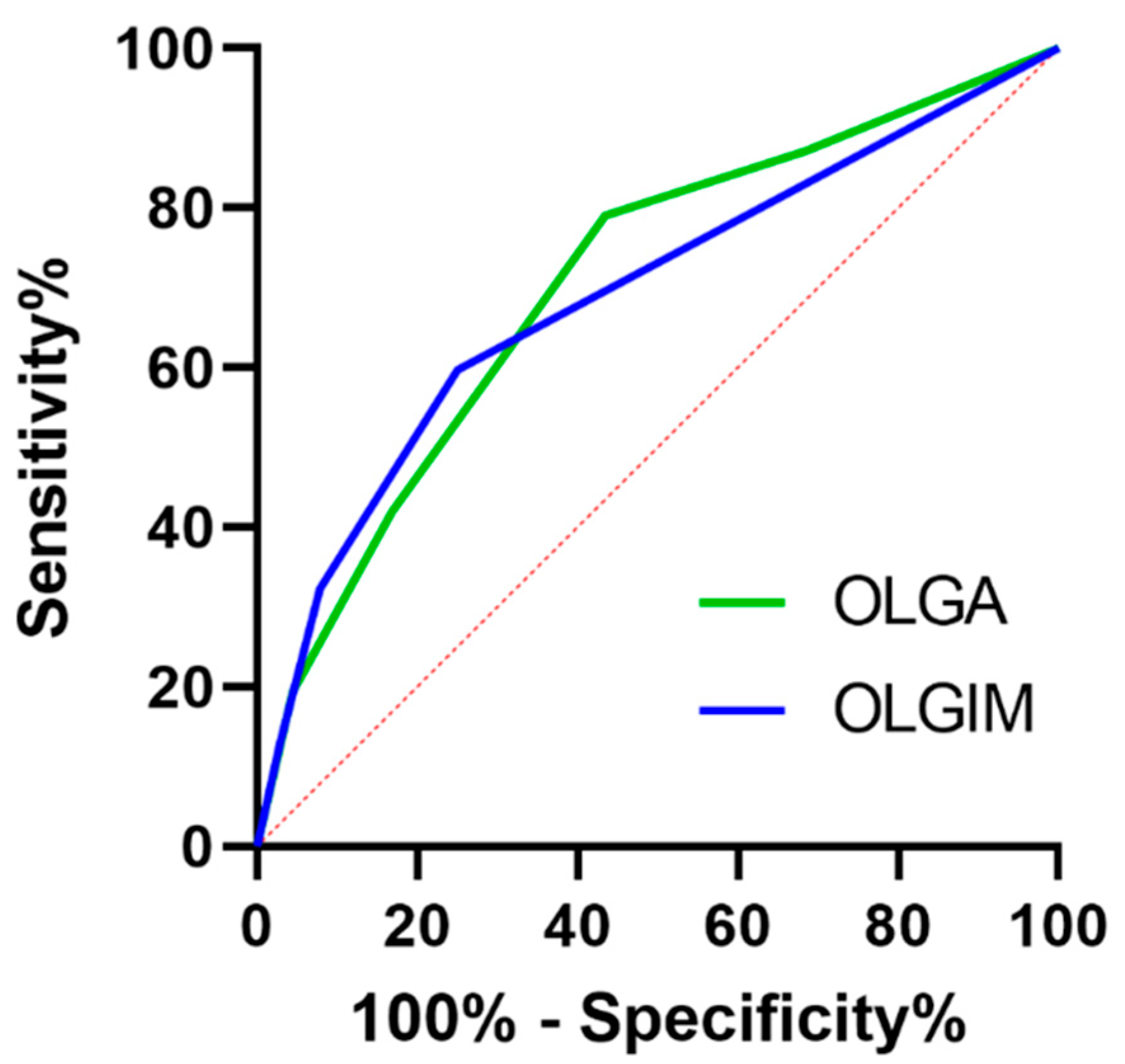

- Early detection of precancerous conditions (GPC) including atrophic gastritis (AG), intestinal metaplasia (IM), and dysplasia is crucial for gastric cancer (GC) management. This retrospective study analyzed 442 single gastroscopies to evaluate the relationship between endoscopy and histological findings including Operative Link for Gastritis Assessment (OLGA) and Operative Link for Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) stagings in detecting advanced gastric precancerous conditions (GPCs) in patients with GC risk factors. Despite high specificity (~89%), endoscopic sensitivity was low (32.5% for OLGA III/IV, 40% for OLGIM III/IV), highlighting the need for systematic gastric mapping biopsies. Male sex and dysplasia were linked to a higher risk of extensive gastric IM. Interestingly, patients with a family history of gastric cancer more often had OLGA/OLGIM 0-II. These findings emphasize the importance of personalized risk assessment, integrating demographic and environmental factors in planning optimal time of screening gastroscopy and surveillance in high-risk GC populations.

- What’s New

- Our study is one of the few that assesses the effectiveness of a single high-quality gastroscopy in identifying precancerous gastric conditions in a low-to-moderate-incidence population (Poland). We observed that individuals with a family history of stomach cancer more often had lower OLGA/OLGIM stages, which may indicate earlier detection of changes and the effectiveness of previous H. pylori eradication. Furthermore, we demonstrated that male sex is associated with a higher risk of advanced intestinal metaplasia, highlighting the need for individualized surveillance strategies. Despite the use of a high-quality endoscopic protocol, diagnostic sensitivity remains low, confirming the importance of systematic mapping biopsies in this patient group and the need for further training of endoscopists.

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

- Family history of gastric cancer (GC) and either:

- Age ≥45 years and no prior gastroscopy or

- Last gastroscopy performed ≥3 years ago.

- Extensive gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM), (OLGIM III/IV) documented in previous reports, with last gastroscopy performed ≥3 years ago.

- Extensive gastric atrophy (AG), (OLGA III/IV) documented in previous reports, with last gastroscopy performed ≥3 years ago.

- Gastric dysplasia (low grade/indefinite) documented in previous reports, with last gastroscopy performed ≥1 year ago.

- Use of high-definition resolution Olympus® (Hamburg, Germany) endoscopes with VCE, water jet and CO2 insufflation, no magnification nor distal cap.

- Oral administration of 600 mg N-acetylcysteine solution 15 min prior to the examination to improve mucosal visibility [11].

- Procedures performed under analgosedation, with intravenous midazolam and fentanyl.

- Minimum procedure time of 15 min, with at least 7 min focused on gastric mucosa assessment using WLE and VCE.

- Random biopsy sampling conducted in accordance with the updated Sydney protocol, with additional target sampling from suspicious areas [12].

- Photo documentation comprising at least 22 images per procedure, following the systematic screening protocol (SSS), plus images of any abnormal findings [13].

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlowska, J.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, M.; Maciejewski, R.; Sitarz, R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaaleh, S.; Alomari, M.; Rashid, M.U.; Castaneda, D.; Castro, F.J. Gastric intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer prevention: Watchful waiting. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2024, 91, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugge, M.; Genta, R.M.; Fassan, M.; Valentini, E.; Coati, I.; Guzzinati, S.; Savarino, E.; Zorzi, M.; Farinati, F.; Malfertheiner, P. OLGA Gastritis Staging for the Prediction of Gastric Cancer Risk: A Long-term Follow-up Study of 7436 Patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, H.; Shan, L.; Bin, L. The significance of OLGA and OLGIM staging systems in the risk assessment of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 2018, 21, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Libânio, D.; Uchima, H.; Spaander, M.C.; Bornschein, J.; Matysiak-Budnik, T.; Tziatzios, G.; Santos-Antunes, J.; Areia, M.; Chapelle, N.; et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and early neoplasia of the stomach (MAPS III): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG) and European Society of Pathology (ESP) Guideline update 2025. Endoscopy 2025, 57, 504–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.B.F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, P.; Xu, B.; Peng, D.; Yang, M.; Tan, Y.; Cai, C.; Li, H.; et al. Magnifying endoscopy in detecting early gastric cancer: A network meta-analysis of prospective studies. Medicine 2021, 100, e23934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cai, M.-X.; Tian, B.; Lin, H.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Yang, X.-C.; Lu, L.; Li, L.; Shi, L.-H.; Liu, X.-Y.; et al. Setting 6-Minute Minimal Examination Time Improves the Detection of Focal Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Lesions During Endoscopy: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romańczyk, M.; Ostrowski, B.; Lesińska, M.; Wieszczy-Szczepanik, P.; Pawlak, K.M.; Kurek, K.; Wrońska, E.; Kozłowska-Petriczko, K.; Waluga, M.; Romańczyk, T.; et al. The prospective validation of a scoring system to assess mucosal cleanliness during EGD. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepan, M.; Fojtík, P.; Psar, R.; Hanousek, M.; Sabol, M.; Zapletalova, J.; Falt, P. Administration of maximum dose of mucolytic solution before upper endoscopy—A double-blind, randomized trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 35, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotelevets, S.M.; A Chekh, S.; Chukov, S.Z. Updated Kimura-Takemoto classification of atrophic gastritis. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 3014–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, D.; Frias, J.; Vera, F.; Trejos, J.; Martínez, C.; Gómez, M.; González, F.; Romero, E. GastroHUN an Endoscopy Dataset of Complete Systematic Screening Protocol for the Stomach. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, B.E.; Pérez-Cala, T.; Gomez-Villegas, S.I.; Cardona-Zapata, L.; Pazos-Bastidas, S.; Cardona-Estepa, A.; Vélez-Gómez, D.E.; Justinico-Castro, J.A.; Bernal-Cobo, A.; Dávila-Giraldo, H.A.; et al. The OLGA-OLGIM staging and the interobserver agreement for gastritis and preneoplastic lesion screening: A cross-sectional study. Virchows Arch. 2022, 480, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Park, J.Y.; Camargo, M.C.; Lunet, N.; Forman, D.; Soerjomataram, I. Is gastric cancer becoming a rare disease? A global assessment of predicted incidence trends to 2035. Gut 2020, 69, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Schulz, C.; Hunt, R.H. Helicobacter pylori Infection: A 40-Year Journey through Shifting the Paradigm to Transforming the Management. Dig. Dis. 2024, 42, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; Rokkas, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Liou, J.-M.; Schulz, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Hunt, R.H.; Leja, M.; O’MOrain, C.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: The Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut 2022, 71, 1724–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.K.; Choi, K.D.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, K.W.; Kim, D.H.; Song, H.J.; Lee, G.H.; et al. Endoscopic scoring system for gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia: Correlation with OLGA and OLGIM staging: A single-center prospective pilot study in Korea. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romańczyk, M.; Ostrowski, B.; Budzyń, K.; Koziej, M.; Wdowiak, M.; Romańczyk, T.; Błaszczyńska, M.; Kajor, M.; Januszewski, K.; Zajęcki, W.; et al. The role of endoscopic and demographic features in the diagnosis of gastric precancerous conditions. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Kim, N.; Lee, H.S.; Choe, G.; Jo, S.Y.; Chon, I.; Choi, C.; Yoon, H.; Shin, C.M.; Park, Y.S.; et al. Correlation between Endoscopic and Histological Diagnoses of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia. Gut Liver 2013, 7, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokkas, T.; Ekmektzoglou, K. Current role of narrow band imaging in diagnosing gastric intestinal metaplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of its diagnostic accuracy. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2023, 36, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jia, Q.; Chi, T. U-Net deep learning model for endoscopic diagnosis of chronic atrophic gastritis and operative link for gastritis assessment staging: A prospective nested case–control study. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2023, 16, 17562848231208669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Feng, S.; Qian, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, K. Helicobacter pylori Infection Combined with OLGA and OLGIM Staging Systems for Risk Assessment of Gastric Cancer: A Retrospective Study in Eastern China. Risk Manag. Heal. Policy 2022, 15, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, M.; Graham, D.; Jansen, M.; Gotoda, T.; Coda, S.; di Pietro, M.; Uedo, N.; Bhandari, P.; Pritchard, D.M.; Kuipers, E.J.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients at risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut 2019, 68, 1545–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romańczyk, M.; Ostrowski, B.; Barański, K.; Romańczyk, T.; Błaszczyńska, M.; Budzyń, K.; Didkowska, J.; Wojciechowska, U.; Hartleb, M. Potential benefits of one-time gastroscopy in searching for precancerous conditions. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzyń, K.; Pelczar, M.; Romańczyk, M.; Barański, K.; Hartleb, M. The survey of willingness to undergo screening gastroscopy in the population of low-to-moderate prevalence rate of esophageal and gastric cancers. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Patients, n | 442 |

| Age | Years |

| Mean (SD) | 59 (12.53) |

| Median (IQR) | 56 (16) |

| Minimum | 33 |

| Maximum | 93 |

| Sex | |

| Men/Women, n | 123/319 |

| Indications for endoscopy, n (%) | |

| Family history of gastric cancer | 160 (36.2) |

| History of atrophic gastritis | 249 (56.33) |

| History of intestinal metaplasia | 226 (51.13) |

| History of dysplasia | 108 (24.43) |

| Endoscopic results, n (%) | |

| Normal | 380 (85.97) |

| Suspicious | 62 (14.03) |

| Histological results, n (%) | |

| OLGA 0–II | 352 (79.64) |

| OLGA III–IV | 90 (20.36) |

| OLGIM 0–II | 392 (88.69) |

| OLGIM III–IV | 50 (11.31) |

| Dysplasia LGD | 149 (33.71) |

| Dysplasia HGD | 3 (0.68) |

| Additional findings | |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 37 (8.37) |

| GEP NETs | 8 (1.81) |

| Gastric MALT | 1 (0.23) |

| Early gastric cancer | 4 (0.9) |

| Analyzed Factor | Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLGA 0–II | OLGA III–IV | p-Value | OLGIM 0-II | OLGIM III-IV | p-Value | ||

| Family history of gastric cancer | 147 (42.36) | 13 (14.44) | <0.001 | 153 (39.53) | 7 (14) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 93 (26.42) | 30 (33.33) | 0.19 | 101 (25.77) | 22 (44) | <0.007 |

| Female | 259 (73.58) | 60 (66.67) | 291 (74.23) | 28 (56) | |||

| Endoscopy results | Normal | 316 | 64 | <0.001 | 350 | 30 | <0.001 |

| Suspicious | 36 | 26 | 42 | 20 | |||

| OLGA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | OLGA 0–II | OLGA III–IV | N, Total | p Value |

| <45 | 86 (24.43) | 41 (45.56) | 127 | - |

| ≥45 | 266 (75.57) | 49 (54.44) | 315 | <0.001 |

| N, total | 392 | 90 | 442 | - |

| OLGIM | ||||

| Age | OLGIM 0-II | OLGIM III-IV | N, Total | p Value |

| <45 | 103 (26.28) | 24 (48) | 127 | - |

| ≥45 | 289 (73.72) | 26 (52) | 315 | <0.001 |

| N, total | 392 | 50 | 442 | - |

| OLGA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Variable State | p Value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Female | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Male | 0.19 | 1.392 | 0.846 | 2.292 | |

| History of Dysplasia | No | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.17 | 1.434 | 0.857 | 2.399 | |

| OLGIM | |||||

| Variable | Variable State | p Value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Female | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Male | <0.001 | 2.264 | 1.239 | 4.135 | |

| History of Dysplasia | No | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.02 | 2.087 | 1.125 | 3.871 | |

| Dysplasia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Variable State | p Value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Female | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Male | 0.88 | 1.036 | 0.669 | 1.603 | |

| Age | <45 | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| ≥45 | 0.17 | 0.737 | 0.481 | 1.130 | |

| Family history of gastric cancer | No | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Yes | <0.001 | 0.437 | 0.282 | 0.677 | |

| History of atrophic gastritis | No | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.025 | 1.342 | 3.055 | |

| History of intestinal metaplasia | No | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.214 | 1.476 | 3.322 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciechański, K.; Ciechański, E.; Kłosowska-Kapica, K.; Skrzydło-Radomańska, B. Single-Time Gastroscopy in High-Risk Patients: Screening Effectiveness for Gastric Precancerous Conditions in a Low-To Moderate-Incidence Population. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6910. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196910

Ciechański K, Ciechański E, Kłosowska-Kapica K, Skrzydło-Radomańska B. Single-Time Gastroscopy in High-Risk Patients: Screening Effectiveness for Gastric Precancerous Conditions in a Low-To Moderate-Incidence Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6910. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196910

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiechański, Krystian, Erwin Ciechański, Krystyna Kłosowska-Kapica, and Barbara Skrzydło-Radomańska. 2025. "Single-Time Gastroscopy in High-Risk Patients: Screening Effectiveness for Gastric Precancerous Conditions in a Low-To Moderate-Incidence Population" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6910. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196910

APA StyleCiechański, K., Ciechański, E., Kłosowska-Kapica, K., & Skrzydło-Radomańska, B. (2025). Single-Time Gastroscopy in High-Risk Patients: Screening Effectiveness for Gastric Precancerous Conditions in a Low-To Moderate-Incidence Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6910. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196910