Reimbursement Policies of Swiss Health Insurances for the Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Abdominal Tissue Excess After Massive Weight Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

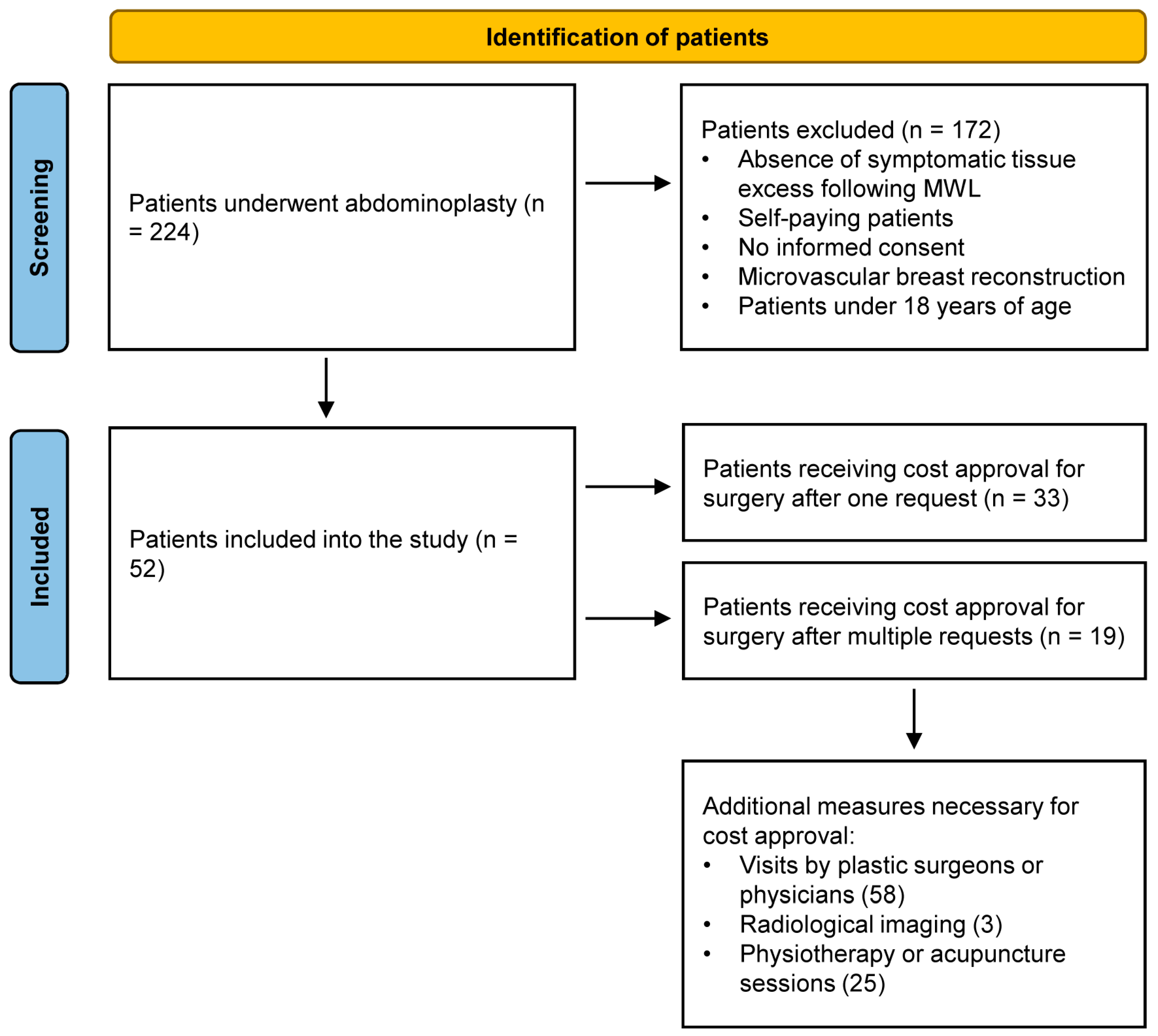

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

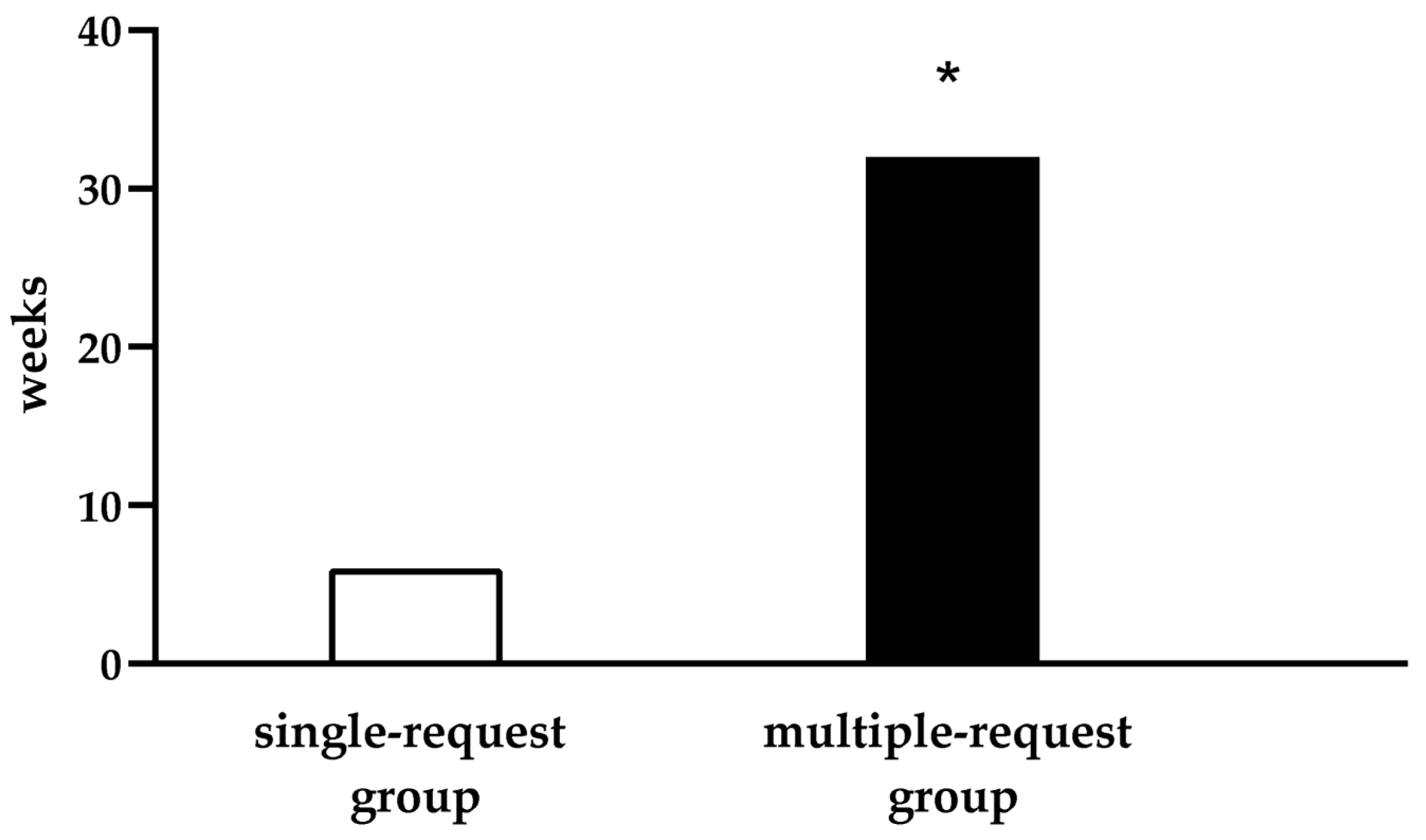

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| HIC | Health Insurance Company |

| MWL | Massive Weight Loss |

| NRS | Numerical Rating Scale |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| Swiss DRG | Swiss Diagnosis Related Group |

References

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Khavjou, O.A.; Thompson, H.; Trogdon, J.G.; Pan, L.; Sherry, B.; Dietz, W. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinl, D.; Holzerny, P.; Ruckdäschel, S.; Fäh, D.; Pataky, Z.; Peterli, R.; Schultes, B.; Landolt, S.; Pollak, T. Cost of overweight, obesity, and related complications in Switzerland 2021. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1335115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaseth, J.; Ellefsen, S.; Alehagen, U.; Sundfør, T.M.; Alexander, J. Diets and drugs for weight loss and health in obesity—An update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.Y.D.; Cox, A.; McNeil, S.; Sumithran, P. Obesity medications: A narrative review of current and emerging agents. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 2024, 6, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovar, A.; Azagury, D.E. Bariatric Surgery: Overview of procedures and outcomes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 54, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froylich, D.; Corcelles, R.; Daigle, C.R.; Aminian, A.; Isakov, R.; Schauer, P.R.; Brethauer, S.A. Weight loss is higher among patients who undergo body contouring procedures after bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016, 12, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldin, M.; Mughal, M.; Al-Hadithy, N. National commissioning guidelines: Body contouring surgery after massive weight loss. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2014, 67, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabbabe, S.W. Plastic surgery after massive weight loss. Mo. Med. 2016, 113, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Picot, J.; Jones, J.; Colquitt, J.L.; Gospodarevskaya, E.; Loveman, E.; Baxter, L.; Clegg, A.J. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2009, 13, 215–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloy, V.L.; Briel, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Kashyap, S.R.; Schauer, P.R.; Mingrone, G.; Bucher, H.C.; Nordmann, A.J. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013, 347, f5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, P.; Duarte-Bateman, D.; Ma, W.; Khalaf, R.; Fodor, R.; Pieretti, G.; Ciccarelli, F.; Harandi, H.; Cuomo, R. Post-Bariatric Plastic Surgery: Abdominoplasty, the State of the Art in Body Contouring. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biörserud, C.; Olbers, T.; Fagevik Olsén, M. Patients’ experience of surplus skin after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2011, 21, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, H.B.; Abayev, S.; Pittermann, A.; Karle, B.; Bohdjalian, A.; Langer, F.B.; Prager, G.; Frey, M. After massive weight loss: Patients’ expectations of body contouring surgery. Obes. Surg. 2012, 22, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, T.; Harling, L.; Athanasiou, T.; Darzi, A.; Ashrafian, H. Does Body Contouring After Bariatric Weight Loss Enhance Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of QOL Studies. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3333–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfanagely, O.; Rios-Diaz, A.J.; Cunning, J.R.; Othman, S.; Morris, M.; Messa, C.; Broach, R.B.; Fischer, J.P. A Prospective, matched comparison of health-related quality of life in bariatric patients following truncal body contouring. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremp, M.; Delko, T.; Kraljević, M.; Zingg, U.; Rieger, U.M.; Haug, M.; Kalbermatten, D.F. Outcome in body-contouring surgery after massive weight loss: A prospective matched single-blind study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2015, 68, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Law on Health Insurance (LAMal), Chapter 8 of Federal Law in Switzerland. Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Manual of the Schweizerische Gesellschaft der Vertrauens und Versicherungsärzte (SGV). Available online: https://www.vertrauensaerzte.ch/manual/4/prac/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Navarra, A.; Schmauss, D.; Wettstein, R.; Harder, Y. Reimbursement policies of Swiss health insurances for the surgical treatment of symptomatic breast hypertrophy: A retrospective cohort study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2025, 155, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colwell, A.S. Current concepts in post-bariatric body contouring. Obes. Surg. 2010, 20, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.Y.; Jean, R.D.; Hurwitz, D.J.; Fernstrom, M.H.; Scott, J.A.; Rubin, J.P. A classification of contour deformities after bariatric weight loss: The Pittsburgh Rating Scale. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2005, 116, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borud, L.J.; Warren, A.G. Body contouring in the postbariatric surgery patient. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2006, 203, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coriddi, M.R.; Koltz, P.F.; Chen, R.; Gusenoff, J.A. Changes in quality of life and functional status following abdominal contouring in the massive weight loss population. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azin, A.; Zhou, C.; Jackson, T.; Cassin, S.; Sockalingam, S.; Hawa, R. Body contouring surgery after bariatric surgery: A study of cost as a barrier and impact on psychological well-being. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 776e–782e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.M.; Faaborg-Andersen, C.; Baker, N.; Losken, A. Evaluating outcomes and weight loss after panniculectomy. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2021, 87, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquette, L.; Skylsen, M. Postpanniculectomy Improvement in low back pain: A case report. Plast. Surg. 2024, 9, 22925503241301708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAbd, R.; Samargandi, O.A.; AlGhanim, K.; Alhamad, S.; Almazeedi, S.; Williams, J.; AlSabah, S.; AlYouha, S. Body contouring surgery improves weight loss after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, S.; Pandya, S. Should a panniculectomy/abdominoplasty after massive weight loss be covered by insurance? Ann. Plast. Surg. 2008, 60, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aherrera, A.S.; Pandya, S.N. A Cohort Analysis of Postbariatric Panniculectomy--Current Trends in Surgeon Reimbursement. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 76, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sumaih, I.; Donnelly, M.; O’Neill, C. Sociodemographic characteristics of patients and their use of post-bariatric contouring surgery in the US. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, S. Panniculectomy, documentation, reimbursement, and the WOC nurse. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2003, 30, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gurunluoglu, R. Panniculectomy and redundant skin surgery in massive weight loss patients: Current guidelines and recommendations for medical necessity determination. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2008, 61, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreifuss, S.E.; Rubin, J.P. Insurance coverage for massive weight loss panniculectomy: A national survey and implications for policy. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016, 12, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Torto, F.; Frattaroli, J.M.; Kaciulyte, J.; Redi, U.; Marcasciano, M.; Casella, D.; Ribuffo, D. Is body-contouring surgery a right for massive weight loss patients? A survey through the European Union National Health Systems. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2021, 44, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühlmann, J.; Lese, I.O.; Grobbelaar, A.; Fischlin, C.; Constantinescu, M.; Olariu, R. Post-bariatric contour deformity correction: An endeavour to establish objective criteria nationally. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilardi, R.; Galassi, L.; Del Bene, M.; Firmani, G.; Parisi, P. Infective complications of cosmetic tourism: A systematic literature review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2023, 84, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria |

|---|

| abdominal tissue excess that causes functional limitations or scar pain |

| association with symptomatic rectus diastasis, possibly confirmed by instrumental examination |

| the abdominal apron must be largely ‘emptied’ following weight loss |

| conservative measures (e.g., drugs, physiotherapy or local treatments) have remained ineffective |

| Service | TARMED-Based Prices (CHF) |

|---|---|

| - evaluation by board-certified plastic surgeon | 136.20 |

| - evaluation by other board-certified specialist | 240.30 |

| - abdominal CT scan | 239.00 |

| - abdominal ultrasound | 146.00 |

| - single session of physiotherapy | 69.30 |

| - single session of acupuncture | 90.20 |

| Baseline Patient’s Characteristics | Single-Request Group (n = 33) | Multiple-Request Group (n = 19) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| gender | |||

| female (n, %) | 23 (69.7) | 15 (78.9) | 38 (73.1) |

| male (n, %) | 10 (30.3) | 4 (21.1) | 14 (26.9) |

| age at surgery (years ± SD) | |||

| comorbidities (% ± SD) | 50.9 ± 11.3 | 46.0 ± 11.6 | 49.1 ± 11.6 |

| smoking (n, %) | 5 (15.1) | 1 (5.2) | 6 (11.5) |

| arterial hypertension (n, %) | 4 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.7) |

| diabetes (n, %) | 3 (9.0) | 1 (5.2) | 4 (7.7) |

| dyslipidemia (n, %) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| chronic kidney disease (n, %) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| sleep apnea syndrome (n, %) | 4 (12.1) | 1 (5.2) | 5 (9.6) |

| height (cm ± SD) | 166.8 ± 9.5 | 166.5 ± 9.3 | 166.7 ± 9.3 |

| BMI before MWL (kg/m2 ± SD) | 46.1 ± 8.4 | 47.3 ± 5.0 | 46.6 ± 7.3 |

| BMI at the time of abdominoplasty (kg/m2 ± SD) | 27.8 ± 4.9 | 29.5 ± 4.2 | 28.4 ± 4.7 |

| weight before MWL (kg ± SD) | 131.9 ± 30.4 | 132.9 ± 14.9 | 132.2 ± 25.6 |

| weight at the time of abdominoplasty (kg ± SD) | 75.9 ± 13.9 | 79.2 ± 10.0 | 77.1 ± 12.6 |

| ideal weight (kg ± SD) | 61.4 ± 7.0 | 61.2 ± 6.8 | 61.4 ± 6.9 |

| excess of weight before MWL (kg ± SD) | 70.5 ± 25.6 | 71.8 ± 12.6 | 70.9 ± 21.7 |

| percentage of weight loss (% ± SD) | 79.6 ± 16.9 | 75.1 ± 11.5 | 78.0 ± 15.2 |

| methods for achieving MWL (n, %) | |||

| gastric bypass | 23 (69.7) + | 12 (63.1) | 35 (67.3) + |

| sleeve gastrectomy | 9 (27.3) + | 3 (15.8) | 12 (23.0) + |

| gastric banding | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.9) |

| diet | 3 (9.0) | 3 (15.8) | 6 (11.5) |

| duration of weight stability after MWL (months ± SD) | 12.7 ± 10.6 | 9.3 ± 5.6 | 11.2 ± 8.8 |

| Health Insurance | Single-Request Group (n = 33) | Multiple-Request Group (n = 19) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| class I | 1 (3.0) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (5.7) |

| class II | 3 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.7) |

| class III | 29 (87.9) * | 17 (89.5) * | 46 (88.5) |

| class I–III | 33 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | 52 (100.0) |

| Cost Coverage | |||

| 100% | 30 (90.9) | 19 (100.0) | 49 (94.2) |

| 75% | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| 50% | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) |

| 50–100% | 33 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | 52 (100.0) |

| Signs and Symptoms | Single-Request Group (n = 33) | Multiple-Request Group (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| skin affections | 31 (93.9) | 19 (100.0) |

| functional impairments | 14 (42.4) | 5 (26.3) |

| psychological disorders | 12 (36.4) | 7 (36.8) |

| symptomatic rectus diastasis | 7 (21.2) | 6 (31.6) |

| severe rectus diastasis + | 1 (3.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| abdominal hernias | 8 (24.2) | 5 (26.3) |

| back pain | 3 (9.1) | 5 (26.3) |

| Diagnostic and Therapeutic Measures | Single-Request Group (n = 33) | Multiple-Request Group (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| visit by plastic surgeons | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.6 ** |

| visit by specialists other than plastic surgeons radiological imaging | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 1.6 ** |

| 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | |

| physiotherapy and acupuncture sessions | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 4.2 * |

| total | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 4.3 ** |

| Specialist | N in the Multiple-Request Group |

|---|---|

| general practitioner | 9 |

| endocrinologist | 6 |

| psychiatrist | 6 |

| dermatologist | 5 |

| neurologist | 2 |

| psychologist | 2 |

| gastroenterologist | 1 |

| general surgeon | 1 |

| orthopedic surgeon | 1 |

| total | 33 |

| Diagnostic and Therapeutic Measures | Single-Request Group (n = 33) | Multiple-Request Group (n = 19) | Cost Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| visits by plastic surgeons + | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 179.2 ± 79.3 ** | 179.2 ± 18.2 |

| visits by other specialists | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 417.4 ± 374.4 ** | 417.4 ± 85.9 |

| radiological imaging | 4.4 ± 25.4 | 27.9 ± 68.6 | 23.5 ± 16.4 |

| physiotherapy and acupuncture | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 94.5 ± 292.1 * | 94.5 ± 67.0 |

| total | 4.4 ± 25.4 | 718.9 ± 446.3 ** | 714.5 ± 102.5 |

| Perioperative Patient’s Characteristics | Single-Request Group (n = 33) | Multiple-Request Group (n = 19) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| type of ‘abdominoplasty’ | |||

| abdominoplasty | 25 (75.7) | 6 (31.6) | 31 (59.6) |

| belt lipectomy | 7 (21.2) | 12 (63.1) | 19 (36.5) |

| panniculectomy | 1 (3.0) | 1 (5.2) | 2 (3.8) |

| weight of resected abdominal tissue (kg) + | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 1.0 |

| percentage of resected surface (%) + | 4.5 ± 0.0 | 5.6 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.0 |

| self-funded concomitant surgeries | 11 ± 0.7 | 6 ± 0.5 | 17 ± 0.6 |

| length of hospital stays (days) | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 5.1 ± 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pruzzo, V.; Bonomi, F.; Guggenheim, L.; Navarra, A.; Schmauss, D.; Wettstein, R.; Harder, Y. Reimbursement Policies of Swiss Health Insurances for the Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Abdominal Tissue Excess After Massive Weight Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186617

Pruzzo V, Bonomi F, Guggenheim L, Navarra A, Schmauss D, Wettstein R, Harder Y. Reimbursement Policies of Swiss Health Insurances for the Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Abdominal Tissue Excess After Massive Weight Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186617

Chicago/Turabian StylePruzzo, Valeria, Francesca Bonomi, Leon Guggenheim, Astrid Navarra, Daniel Schmauss, Reto Wettstein, and Yves Harder. 2025. "Reimbursement Policies of Swiss Health Insurances for the Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Abdominal Tissue Excess After Massive Weight Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186617

APA StylePruzzo, V., Bonomi, F., Guggenheim, L., Navarra, A., Schmauss, D., Wettstein, R., & Harder, Y. (2025). Reimbursement Policies of Swiss Health Insurances for the Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Abdominal Tissue Excess After Massive Weight Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186617