Thymoquinone Versus Metformin in Letrozole-Induced PCOS: Comparative Insights into Metabolic, Hormonal, and Ovarian Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

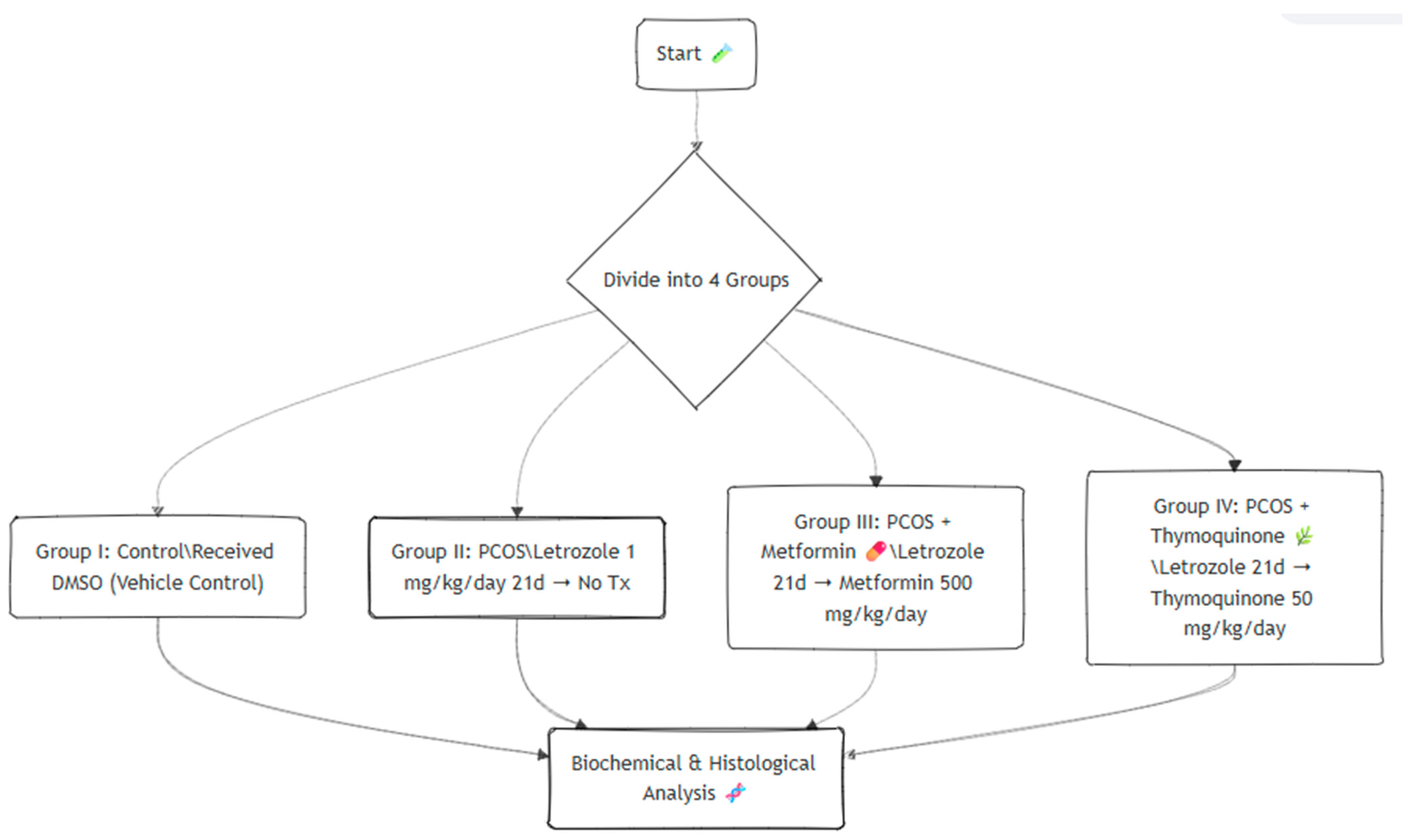

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Treatment Protocol

- Group I (control): Healthy control rats received daily oral gavage with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 21 days.

- Group II (PCOS): Rats were induced with PCOS by oral administration of letrozole (1 mg/kg/day, dissolved in DMSO) for 21 consecutive days, followed by no further treatment.

- Group III (PCOS + MET): PCOS rats treated with metformin (500 mg/kg/day, dissolved in distilled water) for 30 days.

- Group IV (PCOS + TMQ): PCOS rats treated with thymoquinone (50 mg/kg/day, dissolved in distilled water) for 30 days.

2.3. Histopathological Evaluation

- ➢

- Primary follicles: Oocyte surrounded by a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells, without a visible antral cavity.

- ➢

- Preantral follicles: Multiple granulosa cell layers and a well-developed theca interna, no antral cavity.

- ➢

- Antral follicles: Follicles with a fluid-filled antral cavity, multiple granulosa layers, and a defined zona pellucida.

- ➢

- Atretic follicles: Follicles showing degeneration (e.g., granulosa pyknosis, oocyte shrinkage).

- ➢

- Cystic follicles: Large fluid-filled follicles (>1 mm) with a thin granulosa layer, thickened theca interna, and no oocyte.

2.4. Biochemical Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Uterine and Ovarian Weights

3.2. Histopathological Features

3.3. Biochemical Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Body Weight and Glucose Metabolism

4.2. Insulin Resistance

4.3. Lipid Profile

4.4. Hormonal Parameters

4.5. Ovarian Morphology

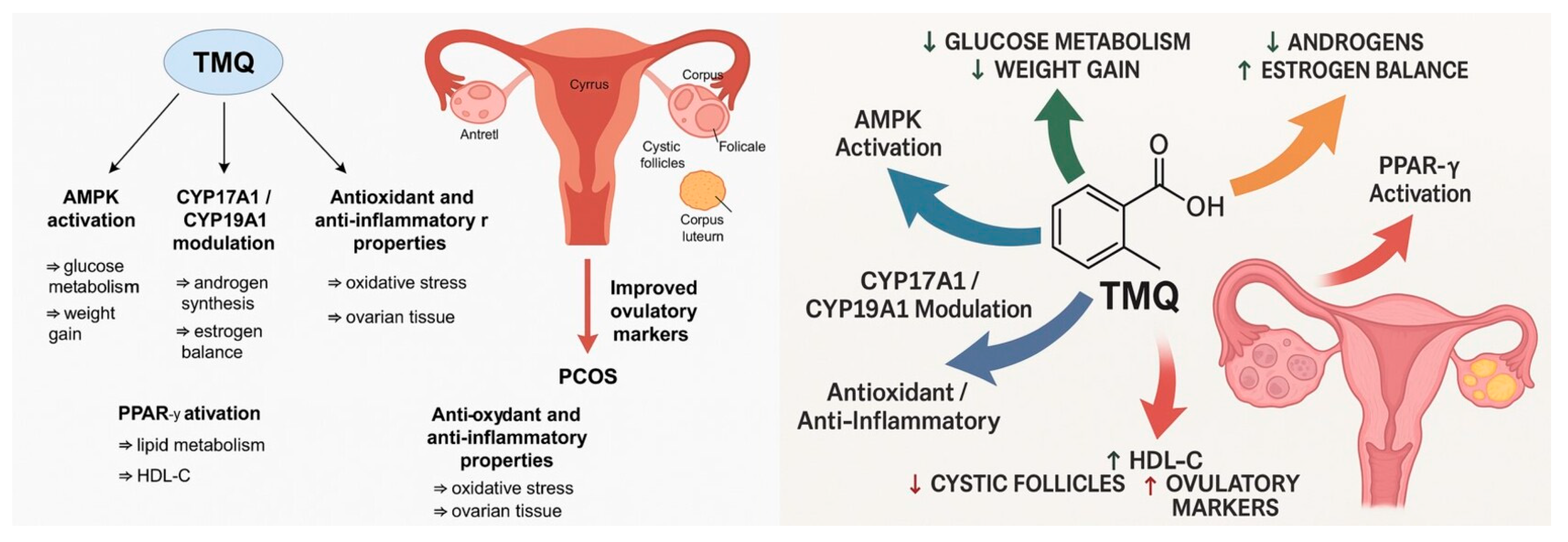

4.6. Clinical Translation and Mechanistic Insights

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stener-Victorin, E.; Teede, H.; Norman, R.J.; Legro, R.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Hoeger, K.; Piltonen, T.T. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joham, A.E.; Norman, R.J.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Legro, R.S.; Franks, S.; Moran, L.J.; Boyle, J.; Teede, H.J. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Liang, W.; Xie, Q. Resistance to the Insulin and Elevated Level of Androgen: A Major Cause of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 741764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, P.; Reddy, S.; Sharma, K.; Johnson, S.; Hardy, G.; Dwivedi, A.K. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Insulin Resistance, and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femi-Olabisi, J.F.; Ishola, A.A.; Olujimi, F.O. Effect of Parquetina nigrescens (Afzel.) Leaves on Letrozole-Induced PCOS in Rats: A Molecular Insight into Its Phytoconstituents. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 4744–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karateke, A.; Dokuyucu, R.; Dogan, H.; Ozgur, T.; Tas, Z.A.; Tutuk, O.; Agturk, G.; Tumer, C. Investigation of Therapeutic Effects of Erdosteine on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in a Rat Model. Med. Princ. Pract. 2018, 27, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, Z.; Ahmad, S.; Usmani, Z.; Mishra, T.; Najmi, A.K.; Amin, S.; Altaf, A.; Mir, S.R. Prolonged administration of letrozole induces polycystic ovary syndrome leading to osteoporosis in rats: Model development and validation studies. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 10353–10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, L.C.; Warzecha, A.K.; Bulow, N.S.; Bungum, L.; Macklon, N.S.; Yding Andersen, C.; Skouby, S.O. Effects of letrozole cotreatment on endocrinology and follicle development in women undergoing ovarian stimulation in an antagonist protocol. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 1557–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Shrivastava, V.K. Turmeric extract alleviates endocrine-metabolic disturbances in letrozole-induced PCOS by increasing adiponectin circulation: A comparison with Metformin. Metabol. Open 2022, 13, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caglar, K.; Dokuyucu, R.; Agturk, G.; Tumer, C.; Tutuk, O.; Gocmen, H.D.; Gokce, H.; Tas, Z.A.; Ozcan, O.; Gogebakan, B. Effect of thymoquinone on transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) channels in rats with liver ischemia reperfusion model in rats. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2024, 27, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, M.; Dokuyucu, R. Effects of Thymoquinone on Urotensin-II and TGF-beta1 Levels in Model of Osteonecrosis in Rats. Medicina 2023, 59, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Zaidi, A.; Anwar, H.; Kizilbash, N. Mechanism of the antidiabetic action of Nigella sativa and Thymoquinone: A review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1126272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uma Maheswari, K.; Dilara, K.; Vadivel, S.; Johnson, P.; Jayaraman, S. A review on hypo-cholesterolemic activity of Nigella sativa seeds and its extracts. Bioinformation 2022, 18, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeber-Lubecka, N.; Ciebiera, M.; Hennig, E.E. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Oxidative Stress-From Bench to Bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Dey, R.; Sen, D.; Paul, N.; Basak, A.K.; Purkait, M.P.; Shukla, N.; Chaudhuri, G.R.; Bhattacharya, A.; Maiti, R.; et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and its management: In view of oxidative stress. Biomol. Concepts 2024, 15, 20220038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, P.; Reeta, K.H.; Maulik, S.K.; Dinda, A.K.; Gupta, Y.K. Protective effect of thymoquinone against high-fructose diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gozukara, I.; Dokuyucu, R.; Ozgur, T.; Ozcan, O.; Pinar, N.; Kurt, R.K.; Kucur, S.K.; Dolapcioglu, K. Histopathologic and metabolic effect of ursodeoxycholic acid treatment on PCOS rat model. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2016, 32, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xiao, L.; Li, S. Effects of Metformin on Reproductive, Endocrine, and Metabolic Characteristics of Female Offspring in a Rat Model of Letrozole-Induced Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome With Insulin Resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 701590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaee, S.; Mirani, M.; Derakhshan, Z.; Koohpeyma, F.; Bakhtari, A. Thymoquinone improves folliculogenesis, sexual hormones, gene expression of apoptotic markers and antioxidant enzymes in polycystic ovary syndrome rat model. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, S.; Abdollahi, M.; Khalaj, A.; Heidari, H.; Zohali, S. The effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Nigella Sativa seed on dehydroepiandrosterone-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in rats: An experimental study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2021, 19, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.E.; Alaa El-Din, E.A.; El-Shafei, D.A.; Abouhashem, N.S.; Abouhashem, A.A. Protective roles of thymoquinone and vildagliptin in manganese-induced nephrotoxicity in adult albino rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 31174–31184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.; Gilani, A.H.; Mehmood, M.H.; Siddiqui, B.S.; Khatoon, N. Coadministration of black seeds and turmeric shows enhanced efficacy in preventing metabolic syndrome in fructose-fed rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 65, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal Lutfi, M.; Abdel-Moneim, A.H.; Alsharidah, A.S.; Mobark, M.A.; Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Saleem, I.Y.; Al Rugaie, O.; Mohany, K.M.; Alsharidah, M. Thymoquinone Lowers Blood Glucose and Reduces Oxidative Stress in a Rat Model of Diabetes. Molecules 2021, 26, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Singh, A.; Negi, P.; Kapoor, V.K. Thymoquinone: A small molecule from nature with high therapeutic potential. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2716–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatroodi, S.A.; Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Alsahli, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Thymoquinone, the Most Prominent Constituent of Nigella Sativa, Attenuates Liver Damage in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats via Regulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cyclooxygenase-2 Protein Expression. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramineedu, K.; Sankaran, K.R.; Mallepogu, V.; Rendedula, D.P.; Gunturu, R.; Gandham, S.; Md, S.I.; Meriga, B. Thymoquinone mitigates obesity and diabetic parameters through regulation of major adipokines, key lipid metabolizing enzymes and AMPK/p-AMPK in diet-induced obese rats. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosian, S.H.; Boarescu, I.; Boarescu, P.M. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Bioactive Compounds in Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbar, H.S.; Vahora, N.Y.; Shah, H.L.; Azam, M.M.; Islam, T.; Hersi, F.; Omar, H.A.; Dohle, W.; Potter, B.V.L.; El-Gamal, M.I. Promising drug candidates for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) as alternatives to the classical medication metformin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 960, 176119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, A.F.S.; Reis, F.M.; Candido, A.L.; Gomes, K.B.; Tosatti, J.A.G. Influence of metformin on hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Natural compounds in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: A comprehensive review of hormonal regulation and therapeutic potential. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1520695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavyani, Z.; Musazadeh, V.; Golpour-Hamedani, S.; Moridpour, A.H.; Vajdi, M.; Askari, G. The effect of Nigella sativa (black seed) on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohit, M.; Farrokhzad, A.; Faraji, S.N.; Heidarzadeh-Esfahani, N.; Kafeshani, M. Effect of Nigella sativa L. supplementation on inflammatory and oxidative stress indicators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 54, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Control (n = 8) | PCOS (n = 8) | PCOS + MET (n = 8) | PCOS + TMQ (n = 8) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine weight (mg) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | p < 0.01 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.001 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.001 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Ovary weight (mg) | 1.03 ± 0.1 | 1.80 ± 0.3 | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.37 ± 0.1 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Preantral Fc | 3.50 ± 0.6 | 2.37 ± 0.4 | 3.11 ± 0.6 | 1.66 ± 0.1 | NS |

| Antral Fc | 6.00 ± 0.7 | 5.25 ± 0.3 | 5.66 ± 0.6 | 6.44 ± 0.6 | NS |

| Atretic Fc | 4.62 ± 0.3 | 6.37 ± 0.7 | 2.22 ± 0.4 | 3.40 ± 0.3 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.001 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.001 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Cystic Fc | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 0.66 ± 0.2 | 1.11 ± 0.4 | p < 0.01 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Corpus Luteum | 12.88 ± 1.2 | 9.12 ± 1.1 | 14.33 ± 1.3 | 15.00 ± 1.4 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Parameters | Control (n = 8) | PCOS (n = 8) | PCOS + MET (n = 8) | PCOS + TMQ (n = 8) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial rat weight (g) | 261.6 ± 8.0 | 262.6 ± 6.0 | 269.3 ± 11.2 | 279.4 ± 10.7 | NS |

| Last rat weight (g) | 275.3 ± 8.2 | 309.0 ± 7.5 †*** | 294.0 ± 7.4 †** | 305.7 ± 7.5 †* | p < 0.001 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 260.0 ± 15.8 | 341.8 ± 16.8 | 290.2 ± 19.7 | 320.3 ± 13.7 | p < 0.01 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Insulin (IU/mL) | 0.8 ± 0.00 | 3.0 ± 0.01 | 2.3 ± 0.01 | 2.6 ± 0.01 | p < 0.001 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| HOMA-IR | 0.58 ± 0.08 | 2.59 ± 0.14 | 1.65 ± 0.15 | 2.05 ± 0.11 | p < 0.001 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Total-C (mg/dL) | 50.12 ± 2.0 | 56.28 ± 1.9 | 57.23 ± 1.7 | 61.07 ± 1.2 | NS |

| TG (mg/dL) | 45.53 ± 3.8 | 57.90 ± 2.2 | 50.67 ± 2.6 | 50.61 ± 2.3 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 4.75 ± 0.3 | 6.62 ± 0.6 | 4.88 ± 0.3 | 4.87 ± 0.4 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 14.09 ± 1.0 | 11.17 ± 0.4 | 17.44 ± 0.6 | 17.22 ± 1.0 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Parameters | Control (n = 8) | PCOS (n = 8) | PCOS + MET (n = 8) | PCOS + TMQ (n = 8) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrone (E1) (pg/mL) | 112.7 ± 3.2 | 216.3 ± 2.4 | 190.6 ± 4.6 | 176.7 ± 10.3 | p < 0.001 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Estradiol (E2) (pg/mL) | 120.2 ± 8.6 | 83.2 ± 6.7 | 146.8 ± 15.5 | 122.5 ± 12.9 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| E1/E2 ratio | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 2.71 ± 0.20 | 1.43 ± 0.18 | 1.53 ± 0.15 | p < 0.001 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.001 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.001 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Testosterone (TT) (ng/mL) | 3.55 ± 0.59 | 9.01 ± 0.93 | 4.63 ± 0.69 | 5.07 ± 1.15 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS); p < 0.01 (PCOS + MET vs. PCOS); p < 0.05 (PCOS + TMQ vs. PCOS) |

| Androstenedione (AS) (ng/mL) | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | p < 0.05 (control vs. PCOS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ercan, O.; Dokuyucu, R.; Yuksel, E.; Ozgur, T. Thymoquinone Versus Metformin in Letrozole-Induced PCOS: Comparative Insights into Metabolic, Hormonal, and Ovarian Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186561

Ercan O, Dokuyucu R, Yuksel E, Ozgur T. Thymoquinone Versus Metformin in Letrozole-Induced PCOS: Comparative Insights into Metabolic, Hormonal, and Ovarian Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186561

Chicago/Turabian StyleErcan, Onder, Recep Dokuyucu, Ergun Yuksel, and Tumay Ozgur. 2025. "Thymoquinone Versus Metformin in Letrozole-Induced PCOS: Comparative Insights into Metabolic, Hormonal, and Ovarian Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186561

APA StyleErcan, O., Dokuyucu, R., Yuksel, E., & Ozgur, T. (2025). Thymoquinone Versus Metformin in Letrozole-Induced PCOS: Comparative Insights into Metabolic, Hormonal, and Ovarian Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186561