New Challenges and Perspectives in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

1. Introduction

2. An Overview of Published Articles

3. Future Research Related to Published Articles

- Optimizing PCOS diagnosis and preventing complications.

- Develop evidence-based resources and explore optimal information provision.

- Exploring effective lifestyle and weight management strategies.

- Exploring intervention effects on diverse features of PCOS.

- Optimizing preconception care and fertility treatments in PCOS.

- Increased implementation of key areas of lifestyle intervention (diet, exercise, sleep, stress, social support, management of obesity) using personalized and public health initiatives [43].

- Early diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction with biomedical testing for insulin resistance (contribution 4).

- Preconception and antenatal counseling and lifestyle interventions—combined with validated biomedical screening tools—to improve fertility and reduce pregnancy-related complications [44].

- Promotion of screening strategies to identify women at increased risk of cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality due to previous pregnancy-related complications such as gestational diabetes, fetal growth restriction, and pre-eclampsia [45].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AMH | Antimullerian hormone |

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CSI | Chronic systemic inflammation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DHEAS | Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating hormone |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein—cholesterol |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IL | Interleukin |

| INRS | Insulin receptor |

| INS1/2 | Insulin receptor substrate 1 and 2 |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| MASLD | Metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease |

| NCD | Non-communicable disease |

| OGTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PPAR-Ɣ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PRISMA | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SGLT-2 | Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 |

| SHBG | Sex hormone-binding globulin |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TMQ | Thymoquinone |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

List of Contributions

- Ercan, O.; Dokuyucu, R.; Yuksel, E.; Ozgur, T. Thymoquinone Versus Metformin in Letrozole-Induced PCOS: Comparative Insights into Metabolic, Hormonal, and Ovarian Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186561.

- Opydo-Szymaczek, J.; Wendland, N.; Formanowicz, D.; Blacha, A.; Jarza˛bek-Bielecka, G.; Radomyska, P.; Kruszy’ nska, D.; Mizgier, M. A Pilot Study of the Role of Salivary Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of PCOS in Adolescents Across Different Body Weight Categories. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6159. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176159.

- Marschalek, M.-L.; Marculescu, R.; Schneeberger, C.; Marschalek, J.; Hager, M.; Krysiak, R.; Ott, J. Mental Health as Assessed by the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) Scores in Women with and Without Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5103. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145103.

- Parker, J.; Briden, L.; Gersh, F.L. Recognizing the Role of Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Paradigm Shift from a Glucose-Centric Approach to an Insulin-Centric Model. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124021.

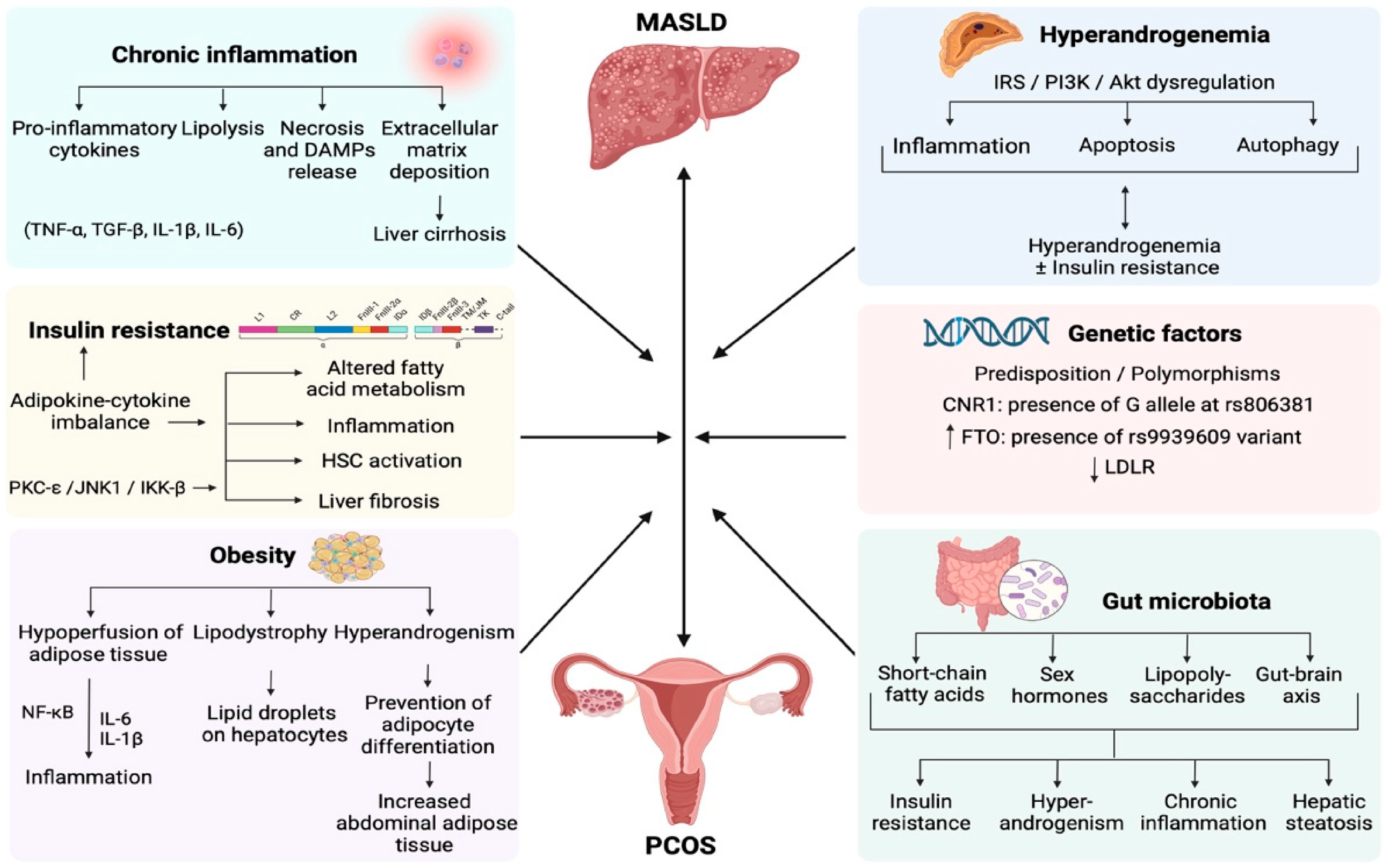

- Arvanitakis, K.; Chatzikalil, E.; Kalopitas, G.; Patoulias, D.; Popovic, D.S.; Metallidis, S.; Kotsa, K.; Germanidis, G.; Koufakis, T. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Complex Interplay. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144243.

- Alenezi, S.A.; Elkmeshi, N.; Alanazi, A.; Alanazi, S.T.; Khan, R.; Amer, S. The Impact of Diet-Induced Weight Loss on Inflammatory Status and Hyperandrogenism in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4934. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164934.

References

- Longman, D.P.; Shaw, C.N. Homo sapiens, industrialisation and the environmental mismatch hypothesis. Biol. Rev. 2025; Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Low, F.M.; Hanson, M.A. Anthropocene-related disease. Evol. Med. Public Health 2020, 2020, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; O’Brien, C.; Hawrelak, J.; Gersh, F.L. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Evolutionary Adaptation to Lifestyle and the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumesic, D.A.; Crespi, B.J.; Padmanabhan, V.; Abbott, D.H. The Endocrinological Basis for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Evolutionary Perspective. Endocrinology 2025, 166, bqaf160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, A.J.; Clark, A.G.; Dahl, A.W.; Devinsky, O.; Garcia, A.R.; Golden, C.D.; Kamau, J.; Kraft, T.S.; Lim, Y.A.L.; Martins, D.J.; et al. Applying an evolutionary mismatch framework to understand disease susceptibility. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, J.; Stella, L. Health Paradigm Shifts in the 20th Century Hospital-based Pathogenic Biomedical. Christ. J. Glob. Health 2015, 2, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Natterson-Horowitz, B.; Aktipis, A.; Fox, M.; Gluckman, P.D.; Low, F.M.; Mace, R.; Read, A.; Turner, P.E.; Blumstein, D.T. The future of evolutionary medicine: Sparking innovation in biomedicine and public health. Front. Sci. 2023, 1, 997136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.J.E.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 189, G43–G64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Health. Cell 2021, 184, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. Pathophysiological Effects of Contemporary Lifestyle on Evolutionary-Conserved Survival Mechanisms in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Life 2023, 13, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palla, I.; Turchetti, G.; Polvani, S. Narrative Medicine: Theory, clinical practice and education—A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xu, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Xu, G.; Ji, X. From Stories to Science: Mapping Global Trends in Narrative Medicine Research (2004–2024). Cureus 2025, 17, e89211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Padmanabhan, S.; Overgaard, S. AI in the doctor-patient encounter. BMJ 2025, 18, r2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, R. Evolution of polycystic ovary syndrome and related infertility in women of child-bearing age: A global burden of disease study 2021 analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 314, 114659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Moran, L.J.; Morman, R.; Gibson, M.; Dokras, A.; Berry, L.; Laven, J.S.; Joham, A.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome perspectives from patients and health professionals on clinical features, current name, and renaming: A longitudinal international online survey. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 84, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stener-Victorin, E.; Padmanabhan, V.; Walters, K.A.; Campbell, R.E.; Benrick, A.; Giacobini, P.; Dumesic, D.A.; Abbott, D.H. Animal Models to Understand the Etiology and Pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 538–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepto, N.K.; Cassar, S.; Joham, A.E.; Hutchison, S.K.; Harrison, C.L.; Goldstein, R.F.; Teede, H.J. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome have intrinsic insulin resistance on euglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clamp. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, R.; Korhonen, S.; Heinonen, S.; Hiltunen, M.; Helisalmi, S.; Hippela, M. Polymorphism in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ gene in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 540–543. [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, S.; Misso, M.L.; Hopkins, W.G.; Shaw, C.S.; Teede, H.J.; Stepto, N.K. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of euglycaemic-hyperinsulinaemic clamp studies. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2619–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumesic, D.A.; Padmanabhan, V.; Abbott, D.H. Polycystic ovary syndrome: An evolutionary metabolic adaptation. Reproduction 2025, 169, e250021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.J.; Avery, J.C.; Moore, V.M.; Davies, M.J.; Azziz, R.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Moran, L.J.; Robertson, S.A.; Stepto, N.K.; Norman, R.J.; et al. Complex diseases and co-morbidities: Polycystic ovary syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Connect. 2019, 8, R71–R75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremellen, K.; Pearce, K. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA)—A novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med. Hypotheses 2012, 79, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; O’Brien, C.; Hawrelak, J. A narrative review of the role of gastrointestinal dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2022, 65, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.G.; Thackray, V.G. Intersection of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and the Gut Microbiome. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvaa177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Ogulur, I.; Mitamura, Y.; Yazici, D.; Pat, Y.; Bu, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, X.; Babayev, H.; Ardicli, S.; et al. The epithelial barrier theory and its associated diseases. Allergy 2024, 79, 3192–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; Brien, C.O.; Uppal, T.; Tremellen, K. Molecular Impact of Metabolic and Endocrine Disturbance on Endometrial Function in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, R. The Common Mucosal System Fifty Years on: From Cell Traffic in the Rabbit to Immune Resilience to SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Shifting Risk within Normal and Disease Populations. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Moar, K.; Maurya, P.K. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 576, 120425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, N.; Szymaczek, J.O.; Formanowicz, D.; Blacha, A. Association between metabolic and hormonal profile, proinflammatory cytokines in saliva and gingival health in adolescent females with polycystic ovary syndrome. BMC Oral. Health 2021, 21, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Li, K.; Wang, Y. The prevalence of anxiety and depression of different severity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybciak, P.; Raczkiewicz, D.; Humeniuk, E.; Powr, T.; Gujski, M. Depression in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, J.J.; MaheshKumar, K.; Radha, V.; Rajamani, K.; Puttaswamy, N.; Koshy, T.; Maruthy, K.; Padmavathi, R. Stress and polycystic ovarian syndrome-a case control study among Indian women. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 22, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaqing, O.; Aspden, T.; Thomas, A.G.; Chang, L.; Ho, M.H.R.; Li, N.P.; van Vugt, M. Heliyon Mind the gap: Development and validation of an evolutionary mismatched lifestyle scale and its impact on health and wellbeing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e07731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.M.; Hanson, P.; Weickert, M.O.; Franks, S. Obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Implications for Pathogenesis and Novel Management Strategies. Clin. Med. Insights Reprod. Health 2019, 13, 117955811987404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R.; Elmquist, J.K. Obesity: An evolutionary context. Life Metab. 2022, 1, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, R.; Ramirez, B.J.B. Strategies to Manage Obesity: Lifestyle. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2025, 21, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanassab, S.; Southern, J.; Olabode, A.V.; Laponogov, I.; Bronstein, M.; Comninos, A.N.; Heinis, T.; Abbara, A.; Izzi-Engbeaya, C.; Veselkov, K.; et al. Identifying nutraceutical targets to treat polycystic ovary syndrome using graph representation learning. npj Women’s Health 2025, 3, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.; Gibson, M.; Laven, J.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.; Piltonin, T.; Costello, M.; Mousa, A.; Joham, A.; Tay, C.; et al. International PCOS guideline clinical research priorities roadmap: A co-designed approach aligned with end-user priorities in a neglected women’s health condition. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 78, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Helm, M.; Tassone, E.C.; Teede, H.J.; Dokras, A.G.R. The Needs of Women and Healthcare Providers regarding Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Information, Resources, and Education: A Systematic Search and Narrative Review. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2018, 36, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garad, R.M.; Teede, H.J. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Improving policies, awareness, and clinical care. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2020, 12, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Maan, P.; Jyoti, A.; Kumar, A.; Malhotra, N.; Arora, T. The Role of Lifestyle Interventions in PCOS Management: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.; Hofstee, P.; Brennecke, S. Prevention of Pregnancy Complications Using a Multimodal Lifestyle, Screening, and Medical Model. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewey, J.; Beckie, T.M.; Brown, H.L.; Brown, S.D.; Garovic, V.D.; Khan, S.S.; Miller, E.C.; Sharma, G.; Mehta, L.S. Opportunities in the Postpartum Period to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Risk after Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, E330–E346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parker, J.; Hitch, V. New Challenges and Perspectives in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8867. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248867

Parker J, Hitch V. New Challenges and Perspectives in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8867. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248867

Chicago/Turabian StyleParker, Jim, and Vanessa Hitch. 2025. "New Challenges and Perspectives in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8867. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248867

APA StyleParker, J., & Hitch, V. (2025). New Challenges and Perspectives in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8867. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248867